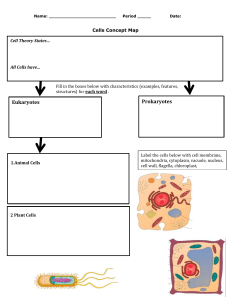

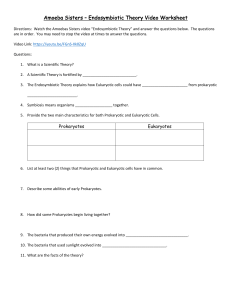

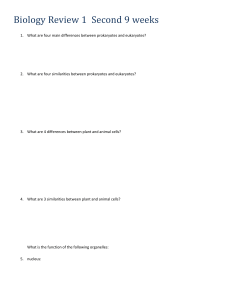

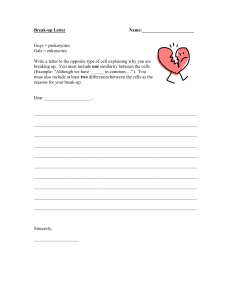

The Endosymbiotic Theory In all living beings, there are two types of cells, prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Prokaryotes are small, containing circular DNA which lies freely in the cytoplasm, while eukaryotes are larger, and have linear DNA contained in a nucleus. Plants, fungi, Protoctista and animals are made up of eukaryotic cells while bacteria are prokaryotes. Prokaryotes are believed to be the ancestors of eukaryotic cells. They were present in approximately 2.7-billion-year-old rocks; hence they are older than eukaryotes which appeared about 1.8 billion years ago. The two types of cells also share many traits, for example, similar genetic codes, enzymes and plasma membranes that could not have evolved independently in different organisms. The endosymbiotic theory states that some of the organelles in eukaryotic cells (mitochondria and chloroplasts) were once prokaryotic cells. The first eukaryotic cell was probably an amoeba-like cell that got nutrients by phagocytosis and contained a nucleus that formed when a piece of the cytoplasmic membrane pinched off around the chromosomes. Some of these amoeba-like organisms ingested prokaryotic cells that then survived within the organism and developed a symbiotic relationship. The prokaryotes provided the eukaryotes with energy since they were able to carry out complex metabolic reactions such as respiration and photosynthesis. On the other hand, the eukaryote provided nutrients for the prokaryotes. Prokaryotes are said to be endosymbionts. This theory was introduced by a scientist named Lynn Margulis in 1970. Her theoretical paper titled “On the Origin of Mitosing Cells” is considered a landmark in modern endosymbiotic theory today, although it was originally rejected many times until being accepted by the Journal of Theoretical Biology. The idea behind this theory leads back all the way to 1883, where botanist Andreas Schimper who was looking at the plastid organelles of plant cells using a microscope, noticed that the plastids divided very similarly to the way some freeliving bacteria did. Then, during the 1950s and 60s, scientists found that both mitochondria and plastids inside plant cells had their own DNA. When scientists looked closer at the genes in the mitochondrial and plastid DNA, they found that the genes were more like those from prokaryotes. Hence, organelles are more closely related to prokaryotes. Lynn Margulis made a similar observation that the mitochondria in cells resembled bacteria. Both bacteria and mitochondria had a double membrane, their own circular DNA and similar methods of reproduction. Using this information as well as that from other scientists, she developed the endosymbiotic theory. Even though she was not the first scientist to make the observation, she was the first to come up with concrete evidence that supports the hypothesis. Some key features that support the theory about these organelles are that they are both double membrane bound, are similar in size to prokaryotic cells, reproduce by binary fission, have their own DNA that is circular and not linear nor enclosed in a nucleus, and they have their own ribosomes which are the same size as those in prokaryotes.