Common Law Estates & Aboriginal Title: Life Estates, Dower, Curtesy

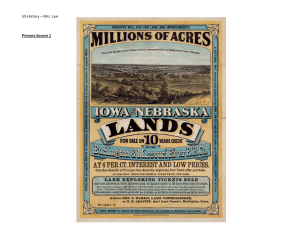

advertisement

400 COMMON LAW ESTATES AND ABORIGINAL TITLE regard to land as a market commodity in nineteenth century England led to refonns that were designed to augment the standard rights of life tenants. In England today, settled estates legislation confers rights of considerable breadth on a life tenant. There is little comparable legislation in Canada. Under Ontario's Settled Estates Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. S.7, a court may authorize certain leases, sales and mortgages of settled land. A life tenant may grant a lease for up to 21 years, provided that the right to do so is not precluded by the original settlement. Such a lease will bind the remainder should the life tenant die before the lease expires. See further O.L.R.C., Report 011 Basic Principles of Land Law (Toronto: A.G. (Ont.), 1996) at 30-60. (d) life estates arising by operation of law The life estates described above arise by virtue of a volitional disposition of property by a private land owner. At common law, two types of life interests in land could arise by operation of Jaw, that is, irrespective of the intention ofthe landowner. Both arose in the context of marriage, and were of some considerable importance under the regime of inheritance known as primogeniture. Under that system, absent a valid testamentary gift, property devolved to the heirs of the landowners. Heirs were premised on consanguinity (blood) not affinity (marriage). As a result, widows and widowers fell outside of the primogeniture rules. In response, a husband could, in defined circumstances, acquire a life estate in his deceased wife's landholding known as "curtesy". A widow's corresponding right was called "dower". The basic elements are described in the extract below. See also B. Murdoch, Epitome of the Laws of Nova Scotia, vol. 2 (Halifax: Joseph Howe, 1832) at 92-4,97-100. W. Renke, "Homestead Legislation in the Four Western Provinces" in J .G. McLeod & M. Mamo, eds., Matrimonial Property Law in Canada (Toronto: Carswell, 1995) I-47.ff[footnotes omitted] (a) The English Dower Inheritance The common-law dower rules have only historical significance. These rules predate the Nonnan Conquest. The common law recognized two relevant types of interests: (a) the "dower" interest of a surviving wife-a life interest in one-third of all lands owned at any time during the marriage by her husband; and (b) the "curtesy" of a surviving husband-a life interest in all lands owned by the wife during the marriage (both at law and in equity) that had not been disposed of inter vivos or by will, if there were children of the marriage. Land sold by a husband during his lifetime remained subject to his wife's dower interest, unless his wife "barred" her rights or, before marriage, the husband conveyed his lands to certain "uses to bar dower". The latter expedient gave the husband the incidents of ownership while THE LIFE ESTATE 40 I avoiding the application of dower. The Dower Act, 1833 abolished dower in land disposed of in the husband's lifetime or by his will and left dower effective only on certain intestacies. The common law, as modified by the Dower Act, 1833, became the received law in British Columbia in 1867, and was later incorporated by statute. The English law as of July 15, 1870 was received in the Northwest Territories. The life of the English law of dower on Canadian soil was short. In 1885, The Real Property Act of 1885 eliminated common law dower and curtesy in Manitoba; in 1886, The Territories Real Property Act eliminated these rules in what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta; and in 1925 these rules were eliminated in British Columbia by the Administration Act Amendmelll Act, 1925. The western provinces now recognize "dower" interests only under statute. (b) Effects of the Repeal of English Dower The main reason for the elimination of the dower and curtesy rules in the western provinces was their inconsistency with the principles of the emerging land titles systems. Dower and curtesy impaired the freedom to transfer lands, and provided for interests which were not disclosed on certificates of title for lands. But while the elimination of these interests did facilitate commerce, a further practical effect was to imperil farm wives and farm families. This effect arose at the conjuncture of two main streams of events. First, to promote the settlement of the West, Parliament had passed the Dominion Lands Act. This Act permitted settlers to purchase certain unappropriated Dominion lands for $1.00 per acre, and permitted settlers to take quarter sections of certain unappropriated lands free, if the settlers homesteaded the lands for three years. The lands were granted to the "head of the family" who was, in most cases, the husband. Husbands, therefore, usually became the sole registered owners of family lands. Second, the prairies experienced a land boom in the early 20th century, leading a substantial number of land-owning husbands to sell or mortgage the family farm, without compensating their wives or sharing the proceeds. The frequent concomitant of speculation is ruin; lands not sold or foreclosed were seized from under families. The economic tragedies that fell on farm women motivated some of the first feminist activism in Canada. Women demanded some legislative protection from the depredations of the marketplace and irresponsible husbands. To some extent, they succeeded. A mark of their success is the homestead legislation in the four western provinces. The homestead legislation provides a counterbalance (slight as it may be) to the free and efficient alienation of lands promoted by modem title systems; it promotes the security of the home. 402 COMMON LAW ESTATES AND ABORIGINAL TITLE (c) The Evolution of the Homestead Legislation The models for Canadian homestead legislation were drawn not from the common Jaw, but from American homestead legislation. American homestead legislation has three main features: (i) it fetters the ability of an owner spouse to dispose of a homestead, without the consent of the non-owner spouse; (ii) it provides the non-owner spouse with a life estate in the homestead upon the death of the owner spouse; and (iii) it wholly or partially exempts the homestead from execution by unsecured creditors. 4. ESTATES IN PERSONALTY B. Ziti, Principles of Property Law 5th ed. (Toronto: Carswell, 2010) at 209-10 [footnotes omitted] The doctrine of estates is inapplicable to personalty; chattels can be owned outright. As a result, at common Jaw an inter vivos gift of a chattel for life, or even for an hour, is treated, in theory, as absolute. The imprint of the English ecclesiastical courts is evident here. These courts, which possessed some jurisdiction over the rules governing personalty, were influenced by Roman law, which had no concept of estates. The common Jaw rule is subject to several substantial qualifications. First, the granting of a temporary interest in a chattel - a bailment - is possible. Borrow a book from the library for two weeks and you will hold a possessory estate-/ike interest. Second, equity will recognize time-limited gifts of personalty contained in a trust. For instance, funds or stocks and bonds might be given to trustees to hold for the benefit of a succession of beneficiaries. Third, it is accepted that the dividing up of the legal title of personalty under a will is valid. If a chattel is bequeathed 'to A for life, then to B absolutely', this creates a type of future interest in B. If the gift is of money. the likely interpretation is that A is entitled only to the interest that the fund generates during the currency of the first interest. Three theories have been advanced to explain the nature of these consecutive rights. Either (i) the title vests immediately in B, with a usufructuary right in A for life; (ii) A becomes the absolute owner, with something called an executory gift over to B; or (iii) A takes the property subject to a trust in favour of B, with either the executor of the estate or the life tenant serving as the trustee. In addition, sometimes estate interests in personalty are introduced through statute. In Alberta, for example, a widowed spouse may acquire a dower right in some of the personal property of the decedent. Despite all of these qualifications on the general rule, estates cannot be created over consumable items that do not form part of stock in trade.