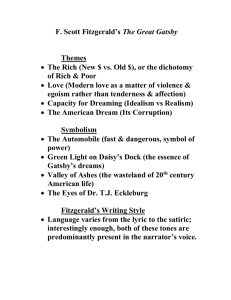

The Great Gatsby: Driving to Destruction with the Rich and Careless at the Wheel Author(s): Jacqueline Lance Source: Studies in Popular Culture , October 2000, Vol. 23, No. 2 (October 2000), pp. 2535 Published by: Popular Culture Association in the South Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23414542 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23414542?seq=1&cid=pdfreference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studies in Popular Culture This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Jacqueline Lance The Great Gats by: Driving to Destruction with the Rich and Careless at the Wheel As one of the most celebrated novels of the century, F. Scott Fitzgerald' The Great Gatsby has attracted significant critical attention, yet despite t quantity of scholarly work, few critics fully examine the automobile trope that permeates the text. Significantly, there are over two hundred references to the automobile in the novel, including references to the "car(s)" (Crosland 51-5 "driving" (and its cognates) (94-95), "garage(s)" (129), and "gasoline" (12 as well as related references to the automobile (Crosland). "As a represent tive figure of the age" (Cowley 133), F. Scott Fitzgerald must have been awa of the cultural impact the automobile was having on his generation, and riddles his best-known novel,-The Great Gatsby, with references to this po lar form of transportation. What is puzzling about the many references to the automobile and the contexts in which it is portrayed is that Fitzgerald pri rily depicts it in negative terms. Apparently, Fitzgerald was not trying to tique the automobile as a form of transportation since he owned a second-ha Rolls Royce (Fahey 66) himself - but was creating a trope in which the au mobile stands for a larger social ill. In order to begin unraveling the automobile trope in The Great Gatsby, recent related scholarship must be examined, beginning with several studi on color-symbolism and the complex pattern of contrasting light and da colors. Daisy's repeated association with the color white has attracted the n tice of several critics, including A.E. Elmore, who observes in his article, "Color and Cosmos in The Great Gatsby, " that "white, even after one exclu near-synonyms such as silver, makes more appearances in the novel than a other single color, and something like three of every four are applied to E Egg or characters from East Egg, especially to Daisy" (428). Furthermore Elmore asserts that "in both the Neoplatonic and Judeo-Christian tradition white ... is symbolic of the One, or of God, or of His abode" (430), a sign cant fact in terms of Fitzgerald's portrayal of Daisy. In his article, "Colo Symbolism of The Great Gatsby, " Daniel Schneider remarks that "white t ditionally symbolizes purity, and there is no doubt that Fitzgerald wants t underscore the ironic disparity between the ostensible purity of Daisy ... a [her] actual corruption" (14). Schneider contends that yellow becomes the "symbol of money, the This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 26 Jacqueline Lance crass materialism that corrupts the dream and ultimately destroys it" (13). Of course, it is Gatsby's dream of winning Daisy's love and respect that is cor rupted by his obsession with possessing wealth and material objects, a wealth that Gatsby believes will ensure Daisy's unwavering love. Appropriately, Gatsby owns a monstrous and fantastic yellow-colored car. In his study Image Patterns in the Novels of Ε Scott Fitzgerald, Dan Seiters examines Fitzgerald's depiction of Gatsby's automobile, namely its "rich cream color" (Fitzgerald 68), which results from the "combination of the white of the dream [Gatsby's] and the yellow of money, of reality in a narrow sense" (Seiters 58). After this car becomes the vehicle of Myrtle Wilson's death, it is simply described as "a yellow car" (Fitzgerald 148). Yellow, as "color imagery unfolds, becomes purely and simply corruption. White, the color of the dream, has been removed from the mixture" (Seiters 58). As white was used primarily to refer to East Egg, "yellow and gold are applied predominately to West Egg and in particular to Gatsby" (Elmore 43 5). Other colors besides white and yellow have symbolic meaning in The Great Gatsby, such as the color blue, which is the color of Tom Buchanan's tasteful coupe. Schneider insists that Fitzgerald uses the color blue to symbol ize a romantic idealism, a continuation of the white imagery that denotes Gatsby's dream (15). Although Schneider does not specifically mention Tom's car in his analysis of The Great Gatsby, one could infer from his analysis of other references to "blue" that Tom, characterized by his blue coupe, was the ideal Gatsby was straining towards. If the color blue is a symbol of Gatsby's romantic dream of attaining Daisy's love, it is appropriate that a blue car should characterize Tom. After all, becoming Tom was Gatsby's dream. Just as the color of the automobile symbolizes a significant aspect of the driver's personality, the car itself further reflects each driver's socieo-economic status in the world of West and East Egg. The most obvious example of this is Gatsby's own car, the Rolls Royce described by Tom later in the novel as a "circus wagon" (128). Seiters suggests that Gatsby's car is the result of his arrested development in adolescence; it is "the very vehicle for one who formed his ideals as a teenager and never questioned them again" (Seiters 58). Gatsby believes that his automobile will advertise his wealth and new status, and it does with unfortunate results; he unwittingly advertises his status as an outsider, one of the nouveau riche of West Egg. While Gatsby's status as one of the nouveau riche is advertised by his yellow car, the Wilson's low social and economic status is advertised by their lack of a running automobile. Fitzgerald portrays George Wilson as an inef fectual man who is trapped underneath the grim reality of his life in the valley of the ashes, "He was a blonde, spiritless man, anemic and faintly handsome. This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Great Gatsby 27 When he saw us [Tom and Nick] a damp gleam of hope sprang into his light blue eyes" (Fitzgerald 29). Wilson is described as an almost lifeless shadow of a man, and his despondency is reflected in the characteristics of the only car that he owns, "the dust-covered wreck of a Ford which crouched in a dim comer" (29). This dilapidated vehicle represents the physical, emotional, eco nomic, and marital deterioration present in Wilson's own life. Furthermore, the sign outside of the Wilsons' garage proclaims, "Repairs. GEORGE B. WILSON. Cars Bought and Sold" (29), a declaration that has a hollow ring to it when it becomes evident that he cannot fix his own car, just as he cannot mend his own life. Myrtle Wilson acutely feels the absence of a working automobile, and like Gatsby, seeks the automobile as a way to bolster her precarious social position. Since Myrtle possesses little wealth and cannot boast of high breed ing, she is reduced to selecting a taxicab she will ride in temporarily. Futilely, Myrtle tries to move into the same social class as the Buchanans and compen sates for her lower economic and social status by ensuring that she can at least ride in style. While the Wilsons desperately strive to own a car that actually runs, Daisy Buchanan can boast of owning a car since her adolescence when she drove a "little white roadster" (Fitzgerald 79). As a married woman, Daisy and her husband possess at least two cars of their own, the blue coupe and the older model car that Tom considers selling to George Wilson. Interestingly, the cars that Daisy and Tom own are barely described; they are simply differ entiated from other vehicles by their colors, "blue" and "white." These under stated cars reflect the understated good taste of the Buchanans; they are com fortable with their wealth and social position and do not need to advertise their status by driving gaudy and showy automobiles. Nick Carraway does not own a showy car, nor does it seem that he wants one. His colorless description of his own car, "an old Dodge" (Fitzgerald 8), is the first reference to an automobile in the novel and serves as an illustra tion of Nick's own social and economic status. Without reserve, Nick estab lishes that he has little wealth and is struggling in his new career in "the bond business" (7), yet he devotes a passage to describing his impressive family lineage of resourceful and respected businessmen. His modest and functional automobile reflects his own sense of satisfaction with his family background and his temporary economic situation. Like Nick himself, Nick's car is the by-product of American ingenuity and follows a tradition of being both reli able and respectable. Although Jordan Baker's experiences with automobiles are crucial to the novel and the automobile trope, her ownership of an automobile is unclear. This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 28 Jacqueline Lance Evidently, Jordan can drive a car; yet Fitzgerald never establishes whether or not she owns a car of her own, just as he never establishes much else about her background. She must come from wealth and breeding since she lives a lei surely life as a professional female golfer and seems to know the "right" people in both West and East Egg. Not only are characters defined by the kind and color of automobile they drive, but the way they behave behind the wheel strongly indicates their attitude towards life and relationships; those who are "careless" drivers ap proach life in the same manner with which they approach the open road. Just as they carelessly cause injury to people and property while behind the wheel, they inflict similar emotional wounds on those with whom they come in con tact. The characters in the novel who are the most careless drivers emerge as those who are the most careless in their personal relationships. As the conversations on careless driving suggest, Jordan Baker oper ates a car much as she approaches life, unreliably and without emotion. Be fore Nick and Jordan have their first conversation about careless driving, Nick narrates an incident that illustrates Jordan's carelessness both with automo biles and in life: When we were on a house party together up in Warwick, she left a borrowed car out in the rain with the top down, and then lied about it—and suddenly I remembered the story about her that had eluded me that night at Daisy's. At her first big golf tournament there was a row that nearly reached the newspapers—a suggestion that she had moved her ball from a bad lie in the semi-final round. (62) The incident starkly reveals Jordan's character, and her misuse of the automobile at the house party anticipates the deception she employs to cover up her carelessness of leaving the borrowed car out in the rain with the top down. After Nick reveals this part of her character, the unsavory story he re calls about her having cheated in a tournament earlier is hardly surprising to the reader. Tom Buchanan is another character who is careless in both life and behind the wheel. The reader learns early in the novel that Tom is having an adulterous affair and is careless enough with his marital relationship that he takes a call from his lover while he is dining at home with his wife and friends. With this in mind, it is not surprising to find out later that Tom is one of the careless drivers of the novel. Later, Jordan reveals to Nick many of the details of the Buchanans' early courtship and marriage, including a distasteful inci This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Great Gatsby 29 dent that occurred in August of 1920, shortly after the couple returned from their honeymoon. According to Jordan's account, Tom was involved in a car accident in which he "ran into a wagon on the Ventura road one night and ripped a front wheel off his car" (Fitzgerald 82). Tom's carelessness extends far beyond his driving on this one particular night; he was accompanied by "one of the chambermaids in the Santa Barbara Hotel" (82) at the time. At the end of the novel Daisy Buchanan is revealed as the most care less of all the drivers. Daisy slides behind the wheel only once in the narra tive, yet her trip becomes one of the most pivotal events of the novel since it simultaneously shows her carelessness behind the wheel and her carelessness with human relationships and anticipates the deception she employs to cover up her crime. Of course, the incident is the hit-and-run accident that kills Myrtle Wilson. We never see Daisy getting behind the wheel until she comments to Gatsby that "she was very nervous" (151) after the confrontation between Gatsby and Tom in New York, and "she thought it would steady her to drive" (151). The narrative reveals that Daisy was driving carelessly by driving too fast and by allowing herself to be distracted by the day's unpleasant events. Finally, after hitting Myrtle with Gatsby's car, Daisy panics and flees the scene, not even stopping to see if her victim survived. Not only does Daisy's careless driving directly result in a fatality, but it leads to other deaths that could have been prevented had she claimed re sponsibility for the accident. Tom and Daisy adhere to the story that neither of them had been involved in the death, leaving Gatsby to take the blame for the accident. Daisy's carelessness behind the wheel clearly reflects the careless ness with which she approaches her love affair with Gatsby. She uses him to appease her own feelings of inadequacy after Tom's numerous affairs and quickly discards him when his existence threatens her own. Throughout the novel, Fitzgerald consistently uses the automobile as a vehicle to reveal the carelessness and materialism of his characters and he extends the scope of the automobile to that most feared and mysterious human condition of all, death. Early in the novel, Nick pairs the automobile with death in his description of Chicago's sorrow at Daisy's absence: "The whole town is desolate. All the cars have the left rear wheel painted black as a mourn ing wreath and there's a persistent wail all night along the North Shore" (14). In this hyperbolic situation, Nick uses the automobile to conjure up images of a funeral scene. Fitzgerald again links the automobile with death when Nick observes a funeral passing during his trip to New York with Gatsby: "A dead man passed us in a hearse heaped with blooms I was glad that the sight of Gatsby's splendid car was included in their [the mourners] somber holiday" (73). That Gatsby's car could have buoyed the spirits of the mourners is pure This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 30 Jacqueline Lance speculation, yet it is clear that the car becomes a part of the funeral and the mourning. Death attaches itself like a contagion to Gatsby's car during this trip, foretelling of the dire events to come. Fitzgerald's careful depiction of the automobile culminates with the hit-and-run accident that kills Myrtle Wilson as the automobile literally be comes a vehicle of death, and Fitzgerald carefully leads the reader to the acci dent by further developing the automobile trope. The tension that leads to the accident begins during the fateful luncheon at the Buchanans when Tom ob serves Daisy and Gatsby together and realizes the two are having an affair. After coming to this realization, Tom agrees to move the party to the city so he can confront the lovers on neutral ground. Interestingly, Tom insists on switching cars with Gatsby, who hesitantly agrees. During this one trip to New York, Gatsby and Tom have switched identities; Tom drives the gaudy yellow car with Jordan and Nick as passengers, while Gatsby positions him self behind the wheel of the tasteful blue coupe with Daisy at his side. While Tom drives the "circus wagon," he feels the pain of Daisy slipping away from him and learns that George Wilson intends to move West with Myrtle since he "just got wised up to something funny the last two days" (Fitzgerald 130), presumably that Myrtle is having an affair. Fitzgerald carefully orchestrates the meeting between Tom and Wilson at the garage to ensure the reader under stands that both George and Myrtle Wilson notice the shiny yellow car Tom is driving. After the confrontation at the hotel in New York, Tom establishes his dominance over Gatsby by insisting that Daisy and Gatsby again ride together, but in Gatsby's own car this time. By switching cars, Tom regains his own identity while relegating Gatsby to his former role as the hopeless dreamer, the one who can never attain his dream. In the same instant that Gatsby's car runs over Myrtle Wilson, the glorious cream-colored car transforms into a "death car" (Fitzgerald 144). All of the negative connotations that Fitzgerald has linked to the automobile cul minate in this terse description, a "death car." Suddenly the automobile has become death itself, leaving a trail of bodies and destruction in its wake. Throughout the novel, Fitzgerald has repeatedly used personification to ani mate automobiles with the personalities of its owners/drivers, and by exten sion, Daisy becomes linked with death as she sits behind the wheel of this "death car." No longer is Daisy Buchanan simply a careless driver. However, Daisy leaves death behind when she slides out from behind the wheel of the now-yellow car and recedes into the security of her social class and her care lessness, leaving death lingering around Gatsby's car and Gatsby himself. References to the automobile dwindle after Gatsby's and Wilson's This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Great Gatsby death, and the "death car" is not mentioned again. Fitzgerald has taken his reader for a metaphorical ride in which he first asserts the importance of the automobile in our society and then repeatedly associates the automobile with negative connotations. Throughout The Great Gatsby, he carefully constructs the automobile trope until it culminates in a symbol of death and corruption. Undeniably, Fitzgerald often portrays the automobile as a profoundly destruc tive force in American society, yet what remains puzzling is why Fitzgerald felt such ambivalence about America's favorite mode of transportation. The riddle of the car's negative role in The Great Gatsby becomes less confounding after examining critical studies that address the role of tech nology in American literature, such as Leo Marx's The Machine in the Gar den: Technology and the Pastoral ideal in America. Marx identifies a recur ring pattern in American mythology, that Americans long for a rural, bucolic setting in which they can escape from the numbing effects of cities and ram pant industrialization. Furthermore, Marx observes that as industrialization became more widespread in the middle of the nineteenth century, the startling appearance of the machine began to surface in American literature. According to Marx, the natural world, or "garden," in The Great Gatsby is a "hideous, man-made wilderness" (3 5 8) that "is a product of the techno logical power that also makes possible (Gatsby's wealth, his parties, his car" (358, emphasis mme). Regarding Gatsby's car, Marx observes: None of his possessions sums up the quality of lite to which he aspires as well as the car... As it happens, the car proves to be a murder weapon and the instrument of Gatsby's undoing. The car and the garden of ashes belong to a world ... where natural objects are of no value in themselves. Here all of vis ible nature is as expendable as a -pasteboard mask ... In The Great Gatsby, as in Walden, Moby Dick, and Huckleberty Finn, the machine represents the forces working against the dream of pastoral fulfillment. (358) Although Marx does not extend his examination of the automobile in The Great Gatsby past this observation, his comments become crucial to under standing Fitzgerald's repeated use of the automobile as a negative force. Just as the pastoral world of Thoreau, Melville, and Twain had been corrupted by technology, so has Fitzgerald's landscape of the 1920s but now it is the auto mobile that is one of the primary corrupting forces, littering the countryside with its unsightly gas stations, clogging the roadways, and providing Ameri cans with a new leading cause of premature death. Further, the image of the This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 31 32 Jacqueline Lance automobile's intrusion into the landscape represents our society in decline, a society that depends on wealth and possessions to define personal worth, a society that allows the wealthy to triumph over and even destroy those who cannot possess the trappings of the rich. In his study "Scott Fitzgerald: Romantic and Realist," John Kuehl supports the theory that the automobile is a crucial trope in The Great Gatsby and concurs with Marx that industrialization and technology, including the automobile, mar the pastoral landscape of the novel: "The valley is bordered by mechanization and urbanization: a highway, a railroad, and Wilson's dingy garage. In front of this garage where Wilson repairs cars, Myrtle, his wife, is killed by an automobile - Fitzgerald's symbol of violent death in the machine age" (417). In addition, Kuehl asserts that Fitzgerald's "interweaving of pas toral nostalgia and cultural history" (416) reflects his belief in a "lost America" (416), a mythological land described by Nick in the following passage: And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I_became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors' eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world, its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby's house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breathin the pres ence of this continent compelled; ο an aesthetic contempla tion he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder. (189) The idealized, pastoral landscape Nick imagined met the gaze of the Dutch sailors has been desecrated in the twentieth century in the name of progress, and the beauty of the natural world has been obliterated by humankind's com pulsion to master the environment, a compulsion that has resulted in an urban ization of the landscape, which creates valleys of ashes. Fitzgerald must have deeply mourned the death of the pastoral landscape and apparently felt that the automobile would be an apt "vehicle" to convey this profound sense of loss. Jacqueline Lance University of South Florida Tampa, Florida This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Great Gatsby 33 WORKS CITED Cowley, Malcolm. Three Novels ofF. Scott Fitzgerald. Charles Scr 1953. Rpt. in Fitzgerald's The Great Gats by: The Novel, The Background. Ed. Henry Dan Piper. New York: Charles Scribn 1970.133-40. Crosland, Andrew T., comp. A Concordance to F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Gre Gatsby. Detroit: Gale Research, 1975. Elmore, A.E. "Color and Cosmos in The Great Gatsby. " Sewanee Review 7 (1970): 427-43. Fahey, William A. F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream. Twentiet Century American Writers. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1973.64-88. Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. 1925. Preface and Notes by Matthew Bruccoli. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. Kuehl, John. "Scott Fitzgerald: Romantic and Realist." Texas Studies Literature and Language: A Journal of the Humanities I (1959): 412-2 Marx, Leo. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Idea America. London: Oxford UP, 1964. Schneider, Daniel. J. "Color-Symbolism in The Great Gatsby. " Universi Review 31 (1964): 13-18. Seiters, Dan. Image Patterns in the Novels ofF. Scott Fitzgerald. Studies Modern. Literature 53. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1986. This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 34 Jacqueline Lance WORKS CONSULTED Allen, Frederick Lewis. Only Yesterday: An Informal History of th Twenties. New York: Harper & Row, 1957. Bewley Marius. "Scott Fitzgerald and the Collapse of the American Modern Critical Views: F. Scott Fitzgerald. Ed. Harold Bloom. N Chelsea House Publishers, 1985. Callahan, John. F. The Illusions of a Nation: Myth and History in th F. Scott Fittzgerald. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 19 Doyno, Victor A. "Patterns in The Great Gatsby. " Modern Fiction S (1966): 415-26. Rpt. in Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: The N The Critics, The Background. Ed. Henry Dan Piper. New York: C Scribner's Sons, 1970. 160-67. Fraser, Keath. "Another Reading of The Great Gatsby. " English S Canada 5 (1979): 330-43. Friedrich, Otto. "F. Scott Fitzgerald: Money, Money, Money." The Scholar 29(1960): 392-405. Knodt, Kenneth S. "The Gathering Darkness: A Study of the E Technology in The Great Gatsby. " Fitzgerald/Hemingway Ann Ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli. Englewood, CO: Information Handling S 1978. Lehan, Richard. The Great Gatsby: The Limits of Wonder. Twayne's Masterwork Studies 36. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1990. MacPhee, Laurence E. "The Great Gatsby's 'Romance of Motoring': Nick Carraway and Jordan Baker." Modem Fiction Studies 18 (1972): 207-12. Mizener, Arthur. The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography ofF. Scott Fitzgerald. NewYork: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1950. Rev. ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1959. Rpt. in Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: The Novel, The Critics, The Backgrounds. Henry Dan Piper. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970. 127-32. This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Great Gatsby Posnock, Ross. "Ά New World, Material Without Being Real': Fitzgerald's Critique of Capitalism in The Great Gatsby. " Critical Essays on F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby Ed. Scott Donaldson. Critical Essays on American Literature. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1984. Rae, John B. The American Automobile: A Brief History. The Chicago History of American Civilization. Ed. Daniel J. Boorstein. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965. Stewart, Lawrence D. "'Absolution' and The Great Gatsby. " Fitzgerald/ Hemingway Annual 1973. Ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli and C.E. Frazer Clark, Jr. Washington D.C.: Microcard Editions Books, 1974. 181-87. Stouk, David. "The Great Gatsby as Pastoral." Major Literary Characters: Gatsby. Ed. Harold Bloom. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1991. Way, Brian. F. Scott Fitzgerald and the Art of Social Fiction. New Y ork: St. Martin's, 1980. This content downloaded from 192.80.65.116 on Fri, 05 Apr 2024 02:09:41 +00:00 All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms