1">

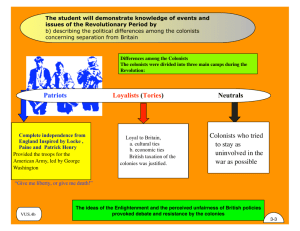

The covers oj Andersm)s

1773 and 1774- almanacs.

14

Almanacs were, after the

WHEN IN THE COURSE

Bible, the genre offrint-ed

matter 'with the greatest

circulation in the colonies.

The l7?4 cover echoes a line

in Isaac Watts)s hymn

{{0, Godf OurHelf in Ages

Past": "Time, like an ever

rolling stream /Bears all

its- sons aiyay."

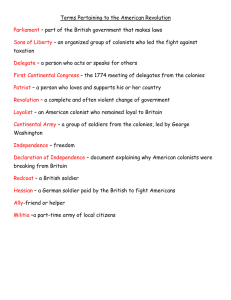

HE! DECLARATION IS NOTHING LESS THAN A VERY SHORT INTRO.

-duction to political philosophy. It teaches us to ask: How are things

going for us? Are we living well, this group of people to which I somehow

WJW", the Year i»~[iiiftan(i gtmc'l

li^^.treams> J's ever rofiine on.

belong? These are the fundamental questions of political philosophy.

At the heart of the Declaration are, as I've said, two ideas: equality and

freedom. What is this equality that the Declaration is about and where is

i£? What and where is this freedom?

These days too many of us think that to say two things are equal"

is to say that they are "the same." Gonsequendy, we think fche assertion

that "all men are created equal," is patently absurd. Everyone hiows

that Bill Gates Is richer, Halle Berry better-looldng, and Albert Einstein

smarter than virtually all of us. And, of course, Bill and Albert are not as

good-looking as Halle, and Halle and Albert are nofc as rich as Bill, and so

on. Everybody is bested by someone at something.

But "equal" and "same" are not synonyms. To be the same" is to be

identical" But to be "equal" is to have an equivalent degree of some spe-

cific quality or attribute. We can be equal in height although we are not

the same as people. In what regard, exacdy, does the Declaration take us

all to be equal to one another?

The matter of freedom is similarly obscure. There is the question of

whose freedom? And from what? Or to do what? And with respect to

[108 ]

READING THE COURSE OF EVENTS

WHEN IN THE

what power? Is it freedom from interference or from domination that

us has for securing the future.

we seek? Aren't all of our lives interfered with by law, after all? Yet these

ars have recendy shown, polii

interfering laws keep us free from domination by others; they protect

erences of the affluent but no

us from exposure to arbitrary treatment and so from uncertainty and

third facet concerns the valu

subordination.

ment of collective intelligence

Aren't we also constrained by the necessity of feeding, housing, and

hand in hand with a well'edu

clothing ourselves and our families? Yet: in meeting these necessides we

ing useful social knowledge i

acquire the capacity to act freely on a. broader canvas,

egalitarian practices ofrecipr

There is, of course, our freedom to vote. But does that freedom trans-

themselves as receiving benel

l^te into any real control? How many of us feel in control of political deci-

them benefits in return? An<

sions made at the state and national level? When property taxes go up

entailed in sharing ownershr

or decisions are made to reduce investment in education, do we feel that

mon world. When we wony,

those are our decisions? And should we even feel in control of decisions

are apathetic, we recognize tY

that constrain our friends, neighbors, and passersby? Should they feel in

having an equal ownership st

control of decisions that constrain us?

These days too many of us have no idea what to make of the concept

Yet important as the argi

of what we get from the Decl

of equality; we are also confused about freedom. I routinely hear from

argument about equality is

students that the ideals of freedom and equality contradict each other.

what it takes for people to fi

The Declaration argues the opposite case: diafc equality is the bedrock of

uncertainty, under the press

freedom.

flourish. Proceeding sentenc

The Declaration starts its argument about equality in its very first

woven threads of this medita

sentence; it follows this salvo with the famous statement that all men are

of the argument about equalj

"created equal"; from there it courses onward to amplify the treatment of

equality with the complaints against King George; finally, it flows out into

its concluding arguments about equality when the signers of the Declara- .

tion pledge themselves and their states to one another. To understand the

argument) we have to pass slowly through each of its phases: the opening

sentence; the important argument about human equality; the remarkable

indictment of King George as a tyrant who violates even basic principles

of reciprocity; and the concluding pledge ofmutualifcy. This we will do,

in reading the Declaration sentence by sentence. In the process, we wiU

master its profound argument about political equality.

There are five facets of the ideal equality for which the Declaration

argues. The first facet, as we are about: to see, describes the Idnd of equal"

ity £hat exists when neither of two parties can dominate the other. The

second facet concerns the importance to humankind of having equal

access to the tool of government, the most important instrument each of

i^

WHEN IN THE COURSE OF HUMAN EVENTS ,..

us has for securing she future. Something has gone wrong when,a

ars have recently shown, poUcy outcomes routinely track the stati

erences of the affluent but not those of the middle class or the po

third facet concerns the value of egalitarian approaches fco the d

ment of collective intelligence. Experts are most valuable when th

hand in hand with a well-educated general population capable of

ing useful social knowledge to deliberations. The fourth facet c

egalitarian practices of reciprocity. How well do citizens do at thi:

themselves as receiving benefactions from their feUow citizens an

them benefits in return? And the fifth facet has to do with the

Ip

entailed in sharing ownership of public life and in co-creatin-g o

at

mon world. When we worry, for instance, that young people don^

ns

are apathetlc,we recognize thatwe^ve failed to cultivate in them a

in

having an equal ownership stake in what we make together.

Yet important as the argument about equality is, it is not tli

;pt

of what we get from the Declaration. There is much more here,(

)m

argument about equality is set in a stunningly moving medlfc

ier.

what it takes for people to find their way forward through cond

: of

uncertainty, under the press of necessity, into a future m which

flourish. Proceeding sentence by sentence, we will trace the seve

irst

woven threads of this meditation and, along the way, also take en

are

of the argument about equality.

.t of

,nto

ara-

.the

mg

able

.pies

[do,

; will

ation

qual-

The

equal

ich of

,1°

JUST ANOTHER WORD FOR RIVER

[ill]

the word "course," has this useful image built into it. We can use this

image of a river to work our way into the sentence.

A river has a definite shape. An infinity of droplets combine into a

single flow, aU moving together in the current's one direction. And all that

water is rolling toward some knowable destination. The muddy Mississippi, for instance, may meander, but it descends inevitably into the Gulf

15

of Mexico.

Now the job is to apply those ideas to human events. As a 1773 almanac puts it, "Time, like a Stream that hastens from the Shore, Flies to an

F

Ocean, where 'tis known no more." Imagine an infinity of human events

flowing together into a great stream and hastening on.

The Declaration is saying that human events, like the infinity ofdroplets in a river, cohere. Human events are going somewhere; they have

shape and direction; there is meaning to their sequence. We should be

able to tell where we are collectively headed. Unlike mindless driftwood,

we should be able to see to the river?s mouth.

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for

Another important feature of rivers helps us understand what the

one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected

Declaration says aJ30Ut human events. It takes a huge amount of work to

them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth,

alter a river's path. The city of Chicago, for instance, spent eleven years

the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and. of

working to reverse the course of the Chicago River so that sewage would

Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions ofman-

flow away from and not into Lake Michigan. Happily, diverting a river

kind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them

and redirecting a river's course are easier than reversing it, even if such

to the separation.

projects take work, too.

That is our begimung, a sentence so long and rich that we can't take

strenuous effort.

The same is true of human events. The course can be altered—with

it aU in widi a single glance. We have to begin by focusing on the very

The phrase "When in the course of Human events, it becomes neces-

beginmngjust one clause to start: "When in the course of human events,

sary" implies that the colonists did not just wake up one day and think,

it becomes necessary for one people..."

lev.en an eutire dause is too much to grasp m one g0-Let7s stop right

here. "When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary... "

That beginning seems overdone. Why not just say, "When it becomes

necessary..."? Why add "in the course of human events"? And what

exactly is "the course of human events" anyway?

Since "course" is another word for "river" an image of a waterway

lies behind this sentence. Although Jefferson may not have been thinldng

explicidy about rivers when he wrote the first draft, the language itself;

Gee, this looks like a nice day for a revolution." Instead, they had studled the events of the past, including of their own recent experience, and

concluded that those events had, like a river, a current. They were flowuig in a specific direction: King George was becoming a tyrant.

Because events were flowing in such a direction, the colonists had

reached a point where they desired to change course Just like Charles

Prince, the CEO of Citigroup, whom I mentioned above. On a much

fger scale than Mr. Prince, the colonists would have to dig in to redirect

die course ofhuman events.

[112]

J'

READING THE COURSE OF EVENTS

The seventeenth-centuiy English philosopher John Locke, whose

The twentieth century h;

ideas were among those that would influence Madison and the Consritu-

not foreseeing what will befa

tion^s framers, argued that government should rest on the will of the peo-

many European Jews before

pie and that people have a right to revolution whenever their government

most salient. In his memoir

is becoming a tyranny.

winner and Holocaust surviv

The hard part is this: how do you know when a government is turning

into a tyranny?

little town of SigheE treated t\

coming as a fool. He was a m<

Locke answered that their right to revolution required citizens to see

but considered mad. What h<

through the fog and haze of events in order to discern a governments

side sanit/s tree-ringed grcn

true course and destination. He compared the experience to being a pas-

escaped while escape was stil

senger in a ship whose course, despite being continually redirected in

Then there are the cases

small ways, consistendy heads toward a slave market in Algiers. In his

the dangerous rapids lurldi

Second Treatise of Civil Government he wrote,

help. Samantha Power's Pu

provides a whole list of exa

IfaU the World shall observe pretences of one kind, and actions

Rwanda, Srebrenica, Kosovc

of another; arts used to elude the law, and the trust or prerogative

trouble recognizing that a g

[held by the Prince] . .. employed contrary to the end, for which it

and believing in the value of

was given: if... a long Train of Actings shew the Councils all tend-

of genocide.

ing that way, how can a Man any more hinder himself from being

Her book overflows with

perswaded in his own Mind, which way things are going; or from

to see the course being set b^

casting about how to save himself, than he could from believing

genocides. Power describes

the Captain of the Ship he was in, was carrying him, and the rest

itous violence," but also the (

of the Company to [be sold in a slave market in] Alglers, when he

of the facts afc hand in conditi

found him always steering that Course, though cross winds, leaks

don has an agenda. There is

in his ship, and want of Men and Provisions did often force him

rate the true consequences (

to turn his Course another way for some time, which he steadily

any actor may make about Hi

returned to again, as soon as the Wind, Weather, and other Cir-

On the other hand, Powe

cumstances would let him?

could, in contrast to everyor

for instance, about the.Arme

Late in his career Locke would work to undermine slavery in the colony

Morgenthau Sr. examined t

of Virginia, and here he uses the fear of being captured and enslaved by

of annihilation; [Secretary c

Barbary pirates as a metaphor for political anxiety generally.

those same facts and saw a

Gidzens need to see through myriad twists and turns of politics in

quell an internal security thi

order to tell whether their political leaders are steering toward a slave

sing could not? Why do we

market in Algiers. This is a veiy hard thing to do. How are we to tell how

have they honed that make t

things are going for us as a community? How can we see what course

the rest of us? As we trace t

we re on?

cover answers to these quest

JUST ANOTHER WORD FOR RIVER

E COURSE OF EVENTS

sntury English philosopher John Locke, whose

[113]

The twentieth century has provided chilling examples of people's

e that would influence Madison and the Constitu-

not foreseeing what will befall their community, with the experience of

hat government should rest on the will of the peo-

many European Jews before and during World War II being among the

re a right to revolution whenever their government

most salient. In his memoir Mght^ Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize

winner and Holocaust survivor, writes about how the inhabitants of the

s: how do you know when a government is turning

'ItU

.!:iiM

i^itl

litde town of Sighet treated the one man who kept telling them what was

coming as a fool. He was a modern-day Gassandra, pouring out the truth

at their right to revolution required citizens to see

but considered mad. What he described seemed to make sense only out-

aze of events in order to discern a government's

side sanity^s tree-ringed grove. As a consequence, none of the villagers

ition. He compared the experience to being a pas-

escaped while escape was still possible.

liill

m

e course, despite being continually redirected in

Then there are the cases where the passengers of the ship can see

iy heads toward a slave market in Algiers. In his

the dangerous rapids lurking just beyond the horizon but can t get

. Government he wrote,

help. Samantha Power's Pulitzer Prize-winning A Problem from Hell

IIIB

provides a whole list of examples: Armenia, Cambodia, Iraq, Bosnia,

9

dl oLserve pretences of one Hnd, and actions

Rwanda, Srebrenica, Kosovo. Power asks why Americans have so much

d to elude the law, and the trust or prerogative

trouble recognizing that a genocide is occurring or is about to occur

... employed contrary to the end, for wliich it

and believing in the value of a strong response against the perpetrators

ng Train of Actings shew the Councils all tend-

of genocide.

an a Man any more hinder himself from being

Her book overflows with stories ofhow the majority of people failed

wn Mind, which way things are going; or from

to see the course being set by political leaders and future perpetrators of

to save himself, than he could from believine

genocides. Power describes "an instinctive mistrust of accounts ofgratu-

Ship he was in, was carrying him, and the rest

itous violence,'" but also the difficulty of settling on a clear understanding

[be sold in a slave market in] Algiers, when he

of the facts at hand in conditions where nearly every- purveyor ofinforma-

fceering that Course, though cross winds, leaks

tion has an agenda. There is; in addition, the difficulty of trying to sepa-

nt of Men and Provisions did often force him

rate the true consequences of a pattern of actions from whatever claims

another way for some time, which he steadily

any actor may make about his actions.

as soon as the Wind, Weather, and other Cir-

let him?

:i;:nn

HIB?1

Ill

^11

;i"^l

On the other hand. Power records minority reports from people who

could, in contrast to everyone else, see what was happening. She writes,

for instance, about the Annenian genocide that "U.S. ambassador Henry

^ would work to undermine slavery in the colony

Morgenthau Sr. examined the facts and saw a cold-blooded campaign

•e uses the fear of being captured and enslaved by

of annihilation; [Secretary- of State] Robert Lansing processed many of

^aphor for poJificai anxiety generaUy.

those same facts and saw an unfortunate but understandable effort to

;e through myriad twists and turns ofpoUdcs in

quell an internal security threat." Why could Morgenthau see what Lan-

their political leaders are steering toward a slave

sing could not? Why do we call some people "farsighted"? What skills

> is a very hard thing to do. How are we to tell how

have they honed that make them better readers of unfolding events than

as a community? How can we see what course

the rest of us? As we trace the argument of the Declaration, we will discover answers to these questions.

Slll:i

CTI

^^EBW^^^t^D^

tEtlierf;it,'non?.l)pl,rwrt'i>;ru(nreiititei-- ;' ,,, i

And when tAa.ffloK'O^Ui'tU fiy^r, rfieydtfnat-i

Theif tremblina Htirit ^[y thpirjbo*ft!cg Tongnu, •'

Divlna bat-pEepiiiiUBdircoyCT'ttjW9r?jT.:.' ."i. ,...' i

And 4raw.^edfft*n(Ltnd(ldp»f they plyfa,; .;,;• . •

';But wlip'tiu c'yr.^cturo'd (fopi thofe ^JBhc ^ee1°P)j •;.^oiteHAeurMunui* jaod^elxte their in »tl'.\ . ;,

jall^uirt." i U*y ^fnlorni j f.i^Q'a'"-!^ pay ((^liaht.

^M^Mopn fi D*y ;i_ Mom. | FulLMiwi; ;a'i Wf 9 ?e!'t

A^C*Wi4?<fl^M'fr;y"i'.CF^:.ff Q5:f\SM,9'){KR^S\

-~TS~

'0:iHr»- .^.alc?

o i6

?>(7

E-^

'•ft.n f rfii6^,.

•^ .»9. ' .a<l

'i7

Spme Wjum. tf^e*thcr

7 *S\Ith^t * y\

^f 'violent Windt

8 1^1

3 33]

^

$

19

«7l6

ctciM off cold

! Uprfr foul fl 3Si

..a7

lincu

4 3S[

58 6' 10 !3\ lt£l ji'^l

fm,(*tf,yif^Mjl, t8[S 566 n 44i . *7

[Ctlil

iV?M.(htiI,&HiehTid<a!

"6 11 ^ fc«

?W. y^'s

jef •^'6i 1 jOj *T 8 'i!

7i<i 01bf»l!J"gWM[lier,l i.'t

* 3l| hc.d 9 >(1

Sup, C. P«nfis. Inf. C.!

*^

if Snaur,

Wf. V eoo^siwdinej

;Irif..C< iifTtbsmften

Fft^i

ij6

IFu^r, but_the Tnvct.l

;fer. i<,*(Ttu!i<!il ^y a

• .NOI th •wetter. ;

^AJur .<!)« Ac ,c61d|

icitjitti nltici.i nuksi

^Aere*tSllrL»(»Api>.|

;3]3uR,C.^Mt PJ'Jr/t,u\

4t8tf.i((Ipf.C,^>CMit.i

" fitt :£Iunen[t. . ;

I; V'yufnU fnts^ify

1,'/UW, ff^jffo?'/^]

IMWcQf' t!n\lt^&?ifn\

,;Biijki{'wl>lt!>, bftff

!Srip;C,?^w»', ;

ms

^

;o G,

42^

6^\

6 "I

3 *3[

^ ^•i

if6 f6^

6f6 ++61

'•?16 ^'^

,6l6 AQ

a6,! i.o aj|

4 I.6J neck (**-J"1

•^ 4JB 6; ! ?)

1^

•*3

[dm I

tnns

o 37|

1 +:1

l7

7 ioj[bltlfl

*i

» 37|

S 37]

4 »7|

^ i9 61 .•?'^i h^tt i '?'

js i8 e\ f 16] '7

*9 Mft

\byA

^ 6| t.^be{ir\ 6 A

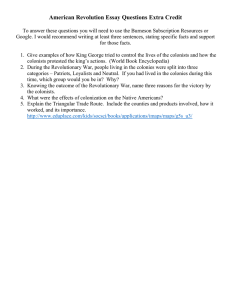

This 1758

almanac captures

the emotional

texture attached

to the desire to fee

the future.

)i 6| a:Mi ?t 6 i7

u

j&6

t 16; rein >

7",

i '43'.fifwf

-9 ^

! °U^!

aq 6) 1 «i <S

8 4;'

I'o; 4&

When the colonists referred to the course of human events, they were

taking responsibility for observing the currents within human action that

pull us toward destinations, as identifiable—once we arrive, that is—as the

Gulf of Mexico. It is our job as citizens to understand those currents—and

to debate them and their direction—in the public square, so that we can

see, as early as we can, as best we can, and despite the fogs of doubt and

misdirection, the destinations that politicians and leaders are steering

toward.

The very course of human events depends on it.

If

; THE COUR.SE OF EVENTS

rffZTT^R;-r'A^ .28 Dtfyj

rt.u none but.fun * future ?tite ,•

enthe.moft'Obduratsrww, thtydcfnat

ng Hearta btly thFir.lMaSicg Tengau.

cip oft undirco»cr'd World*,

; diitint Ltnd&ip u they plufe:

;'cr retura'd fiom Aofe brigiit.Riiglom,

UiBii"* ; and refttc their Law)? . ,

16

lay 4Moro. j:t(ir?y2ar(.-lj)..£)ay 6 Mi^x.

la^ t Morn. [j?uU'irft>'n.t3 D»y 9 Night

ai^*tb,^e.O.S^R Q'S.^Si^ysfFS^'s.

:-l6 o i6|

~^:y^\ •i7 S.5j

^-.t6n..i

•\7 4-5]

1.34|

-a9

ai Wc*ther

H7

7 *Sl![higlu a P\

olcnt Wlndi 3417 a si B i6j »7

3 331

off cold

tneca + 35|

•E PEOPLE

S !t

iut ,i3 3 it

S9 6t

7S6 ?B61

5661

rt/fflf,Inf..C.i

,-y. g mraji, asjs

ScHighTidu; ig]6

9 9'^

lingWeutKE,

• legr

+4j a;

i^ * 36[

".*oj

fe<t

^-371

6_^|

S fctt;!

6 "I

*').

8 'sl

ss'6t ' 3S[ hc.d 9 li;

Snow,

?16 So. 6; 3 *}| a6j Ip 351

(oiSIcadtng

i|6. 49 6t 4. '.<'; ncA

,(-1- 3<1

i&amftM

•4S 6|

•»3

Morn I

:.theTrwI-|

*nn!

+7..6J

o 37j

E&ulied bji

i|6 48,6j ^ 36; 17,: 1 +C]

'^ U't -7 aoi biwft

•WcftMi ' 37\

Uc.the ,cDld '?i6

*? 3 37\

ifhiclt maitci.

.8[6 4,0.6]

+ VS\

tirln« Apo. ^3

•i9.6i .9.331 •hurt 5 '3|

•S4..&1

'fi

k61

^6t

3Btc ,f6jL. '7-

fea, .fatrjttU,,

if.c^cS^

Ill •i?-^^

s

'.' *9

f^iyj

:iat&, "3^ <ill«.'.;;43i

1 {nlSjMtsffT.

3i^, ••'?.9i .?.i

'wp.tW^e/c, ^4)6.

;,i6;i'eim..

•)?..U<

•w&it^ iso f tifi':^'t

t"l7iUncBt*.,

^

ii!

Thisl7$8

almanac captures

the emotional

texture attached

to the desire to see

the future.

&S7.

? S3\

8.47,i

143;ft"ef '9:+3|

v.&fftS^iir^ 1615, jo, &I

E^CM :.

l?» a» 6) i^)!t- *t H.l^fcl

"HE OPENING PHRASE OF THE DBCLABATION, .^N IN THE COFME

Uhuman'events," stands as an assertion by «hecolomste_°^thfflr

fa^sTghtednesTlt offers us an invitation to adopt their line of sight. From

)int, what exactly do they see? ^ , . , .

^n'&'eTp^mng' sentence of the Declaration, the c°l°msteclam'Ml

the basis'of having examined the course °fhu^ events, Aa^eysee^

nists referred to the course of human events, they were

fcy for observing the currents within human action that

tmafaons, as identifiable—once we arrive, that is~as £he

is ourjob as citizens to understand those currents—and

d their direction—in the public square, so that we can

can, as best we can, and despite the fogs of doubt and

destinations that politicians and leaders are steering

the am^Jofa moment of necessity. They say, "When in the Course <

human '^itbeco^s necessary for one people to dissolve Ac polito

bands connecting them with another.._. adecentresPecttoth^pm0^

of'mmUnd'iequLes that diey should declare the[ir] causes." This^l

right to a second question about necessity. In what sense is it necessaiy

for the colonists to separate firom Britain? _ . . , , .

~ The colonists haven't yet been explicit about why their revolution is a

matter of necessity, but the metaphor of a river's course provides a hint..

ie of human events depends on it.

river is puUed inescapably downward by gravity. Are the colonists saying

that some necessary law of nature drives them onward too?

"The'endofthe sentence, where the colonists say that -they shou

declare the causes which impel them to the separation," provides some

confirmation of this idea. "Imper means that somedun^Pret^strong

is" pushing them. Both "propel," which means "push forward?^

:'^per:w1uch means "push out" are related to it. But to be "impdled"

[116]

READING THE COURSE OF EVENTS

ONE PEOPLE

[11?]

if we are to be precise about our Latin etymology, is to be "pushed

ity shared many cultural traditions with the British, including the com-

toward" something.

mon law, school curricula, songs, food, and modes of dress. This means

The colonists are not pulled toward the new situation by desire. They

are pushed. They imply that they are driven toward their revolution by

that in the minds of the colonists neither language nor religion, neither

culture nor race, established the boundaries of a people.

something like the law of gravity. They go reluctantly.

This does not mean, though, that they have no choice. They have

Was the answer, then, simply geography? The fact of separation by

the Atlantic Ocean?

felt and registered the force of the river's current, yes. But then they have

made a decision: to swim with that current, rather than against it.

That leaves us with a lingering sense of mystery. What is this strong,

gravifcy-Hke force pushing them on?

There's much more to it than that. When Jefferson wrote the first

draft of the Declaration, "the people" could mean any of three different

things. The term could mean a group bound together by language, loca-

tion, religion, or ethnicity. Or it could be used to describe the poor in

Before we can answer that, we must recognize that this sentence

contrast to the aristocratic and weU-to-do. And in the 1600s and 1700s

throws yet another problem at us. Before we can identify the mysteri-

a third meaning arose through the writings of several eminent philos-

ous gravity-like force driving events onward, we need to be more precise

ophers, includmg Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques

about who is being impelled and to what. I have said that "the colonists"

Rousseau, who were all, in one way or another, out to destroy the idea

are being pushed toward a new situation, but this is not what they say.

that the basis of political rule was a gift from God, passed down kbg to

They say that it has become necessary for "one people" to separate from

king, from Adam. The need for political order—the fact of its coming

another.

to existence—all three argued, emerges from the need of any multitude

The colonists experience the force of necessity as "one people." They

of individuals for collective organization. Not a gift from God, political

experience it collectively and with some degree of unity. That they iden-

order emerges from the human need to gather together peaceably. A

tify themselves as "one people" in the very first sentence of the Declara-

multitude organized politically becomes a people. For these philoso-

tion is surprising. They had long been a very iGracdous set of quite diverse

phers, a ^people" was thus simply a group with shared polidcal institu-

communities-firom all the various parts of England, as well as fi-om Ire-

tions. This third meaning seems the best fit for the first sentence of the

land, Scodand, Wales, the Netherlands, and Germany. Some were Puri-

Declaration. After all, the Declaration is declaring that the residents of

taxis with rigorous demands for personal and public morality; others had

the colonies now have a set of political institutions separate and differ-

been convicts, saved from execution by deportation to the colonies. Yet

ent from those of the mother country.

they open the Declaration by claiming the discovery of their peoplehood,

as a group separate firom, in pardcular, the British.

What exactly distinguishes one people from another m the first

place? Often people Sake it that differences of language, reKgion, or race

disdnguishes peoples, but none of those definitions works here. They

don't work, because they don't capture the specific peoples that the

colonists have in mind: themselves, on the one hand, and on the other,

the British.

The colonists had a lot in common with the people of Great BritaiiL Most of them spoke the same language. They had the same reUgion:

both groups were mainly Christian, even tf there were different flavors of

Christianity in each place. They were of the same "race " and the major-

The thirteen colonies, then, are bound together above all by their

political institutions, even if those institutions have only just hatched.

^

•s^f:

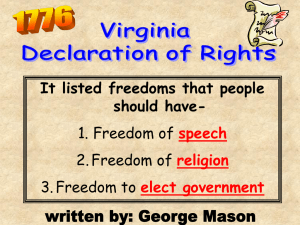

j0w?itnbei^0rnot avail till ih« Colonies are united,^ J^RJ

^hUftdivi^d,theStrength6fAeInhab}taritsi's broken like the]

l^tty'Kmgdomyin^/rj^.—Ifwc do not join He'art and Hand|

I ntfle comI"<)nCaufe againft our exulEing Foe?, buc 6u t0 dif-.l

?uuogamongft oarfelve&, it may really happen as l^enGovc^

Koar.of pennfylv£ma told his Affembly, < We fhallhave'-Bo|

priyHedge lo-difpute about, nor Country to dypute'in.'——

"» " n-ti • ,f * ^ . — ' _ -rf- - :- -r " - - :\\

This 1758 almanac 'written by Nathaniel Ames e-xfresses the unity

of peoplebood AT joimny heart ana hand in common cause.

[118 ]

READING THE COURSE OF EVENTS

On account of their fledgling insdtudons, they now see themselves as

a people separate from the people in England with whom they share a

language, religion, law, cultural traditions, and history. Although the

thirteen colonies are sdll thirteen separate political units and although

their new confederation is not yet a single nation, they have become

one people.

17

Unified now for the first time, the colonists face their grave moment of

necessity together.

fALS

What will this people do with it?

HE FIEST THING THE COLONIES, NOW "ONE PEOPLE," DO WITH

.their shared moment ofneces^ty is make a preposterous-sounding

claim. They say to the kingdom o^&reat Britain, "We are your equals'"

What they actually say is tl^ft it has become necessary for them to

dissolve the political bands ]j^bich have connected them" with Britain

and "to assume among thejpowers of the earth, the separate and equal

station to which the Laws jrfFNature and of Nature's God entitle them."

The colonists are nojfonly separating from Britain but also claiming

to have an "-equal statij^i" to their motherland. "Station" is Latin again

and comes from the ^6rd for "stand." One1s station is where one stands

with people.

A similar idea f rank. A prince has a lofty station high above a peasant who is in a \/w\y station. A clergyman has a reasonably high station

but not as higl^is a prince. The prince gets the most respect, the clergyman the next^fevel of respect, and the peasant the least. In an aristocratic

society, a pfsor^s "station" determines how much respect he gets from

others.

HereJTn the very first sentence of the Declaration the colonists lay

claim. t<jfa. station on the worlcPs stage equal to Britain^. This they do not

ig Britain down but by puUing themselves up. They want respect.

This must have sounded audacious, if not outrageous. Britain boasted

morp than Awp rimp.s as manv Deoole as the colonies. The British navy

EVENTS

(^

ations, they now see themselves as

n England with whom they share a

.difcions, and history. Although the

sparate political units and although

a single nation, they have become

17

; colonists face their grave moment of

HE FIRST THING THE COLONISTS, NOW "ONE PEOPLE," DO WITH

-their shared moment of necessity is make a preposterous-sounding

claim. They say to the kingdom of Great Britain.; "We are your equals'"

What they actually say is that it has become necessary for them "to

dissolve the political bands which have connected them" with Britain

^

and "to assume among the powers of the earth., the separate and equal

station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them "

The colonists are not only separating from Britain but also claiming

to have an "equal station" to their motherland. "Station" is Latin again

and comes from the word for "stand." Onels station is where one stands

with people.

A similar idea is rank, A prince has a lofty station high above a peasant who is in a lowly station. A clergyman has a reasonably high station

but not as high as a prbce. The prince gets the most respect, the clergyman the next level of respect, and the peasant the least. In an aristocratic

society., a person^ station" determines how much respect he gets from

others.

Here in die very first sentence of the Declaration the colonists lay

claim to a station on the world's stage equal to Britain's. This they do not

by pulling Britain down but by pulling themselves up. They want respect.

This must have sounded audacious; if not outrageous. Britain boasted

more than three times as many people as the colonies. The British navy

[120]

READING THE COURSE OF EVENTS

WE. Ait-fi I IJ u B. Fi^U/1.1^13

presided as master of the Atlantic if not the world. Through both tax-

Certainly not. Or, at least, not at first. Not if she was the only per-

ation and the capacity to borrow, its government had powerful tools

son there. The colonists^ claim lias something to do with what they as

for financing war. The Continental Congress had no power to tax and,

a group of people are doing together, not with the size of their territory,

consequently, little power to borrow. The British military had numer-

their wealth, or anything else of that kind.

ous experienced officers and weU-drilled regiments. The colonial mili-

They are the same as the European empires in one way only.

da were no match in numbers or experience. The British political and

Because the colonies had set up shared political institutions, their cit-

legal system dated back to 1066, and the reign ofWiUiam the Conqueror,

izens have acquired a fledgling capacity to organize their collective lives

a descendant ofVildng raiders, who invaded England from Nonnandy.

without help from others and with a clear intention to resist any efforts on

The colonists, as a single people, had only the decisions of the Continea-

the part of others to intervene in their new capacity, as a community, for

tal Congress taken between 1 774 and 1776.

self-government

Perhaps the colonists7 claim to equality might have made more sense

in comparison with the continental nations France or Spain?

This capacity of the colonies to organize their collective Uves was

equal to the capacity of Great Britain, France, and Spain to do the same

Such a claim would have sounded equally preposterous. Along with

for themselves. The remarkable idea expressed here is that neither wealth

Britain, France and Spain were among the eighteenth century s greatest

nor military power increases the capacity of society to organize itself.

powers. After China and India, France had the third-largest population

That capacity is something a society either has or doesn't have. The

in the world, and even Spain, although it had declined from its political

capacity of the colonies for collective self-organization was at a bare min-

apogee at the end of the sixteenth century, had a significantly larger pop-

imum, but it existed.

uladon than the colonies and still held an overseas empire. The newly

Societies have that capacity when they can build functioning polit-

united colonies would have looked, well, puny when placed alongside

ical organizations through which collective decisions can be made that

those great powers.

have the allegiance, whether explicit or implicit, of the people. Wealth

Nevertheless, the colonists assert their equality, as a power or confederadon of powers, to those other powers.

In what regard could these newly united colonies possibly be the

same as the long-lived, vastly wealthy, militarily mighty empires?

and military power increase the capacity of a society to organize other

sodedes but not to organize itself. The capacity of self-organization lies

elsewhere—again, in procedures for decision making and for connecting

citizens to one another in a sense of a shared fate.

Was the physical territory of the colonies perhaps as extensive as

Simply by virtue of achieving this political capacity, the colonies had

that of England, France, and Spain? Only if one pays no attention to the

made themselves an independent political entity, no less and no more

empires possessed by each of those nations. But of course those countries

independent than any of the great powers. They were, for this reason,

had much more land in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Even in regard to

ready to assume, "among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal

land, the colonies looked like welterweights.

station of a self-organizing, sovereign political unit.

Perhaps, then, the colonists were asserting their equality because they

thought they had the potendal to expand to a size equivalent to the European empires?

Territory isn7t really what makes the difference here. Imagine that

a single person had landed by herself on Mars, claimed it as her coun-

The former colonies noted their acquisition of this capacity by dianguig their names from colonies to states.

At last we can see it. That's the meaning of that change of name. A

colony" identifies a social group whose affairs are organized by someone else. A "state" identifies a social group that organizes its own affairs.

try, and declared her new country, "Marsland," equal to the different

Now that we understand the difference between a colony and a state,

nations on earth. Would that claim make any sense? Would she be taken

We can confidendy talk about the newly united "states" that declared

seriously?

independence and, with this declaration, assumed their separate

[122 3

READING THE COURSE OF EVENTS

and equal station among the eartl^s powers. On the basis of their new

capacity for self-government, the new "states" claimed their equality to

other states; they claimed a right to be free from domination.

They were equal to all the great powers in the capacity for political

organization. And this gives us our first flash of insight into the mystery

of what equality means in the Declaration.

It does not mean equal in all respects.

It does not mean equal in wealth.

It does not mean equal in military might.

It does not mean equal in power.

It means equal as a power.

Is this change from in" to as" overly subtle? I think not. If the

newly united states and Britain had been equal "in" power, they would

each have had the same amount of something. Each would have the same

NBVITABLY, TRAGEDY :

capacity to influence the world. But to say that they are equal "as" powers

.Declaration. Shadows,

is to say that they are equal in something that they are. They share a sta-

already on the first sentenc

tus. Each is a society that has learned how to use institutions to organize

That first sentence sho

collective life and achieve collective actions. Once a society learns this, it

does, though, we are likely

is a power because it has learned how to organize and use power, in par-

ing from how often the op(

ticular, the power of words.

more to it than that. An ed

In short, the colonists were saying that "our state is equal to your

state insofar as they are both states.

It s surprising to start talking about equality in the Declaration by

considering how states are equal to each other, but that is the first way the

Listen again. The colo;

the earth, the separate and

of Nature s God entide the

The phrase "separate

concept of equality enters our text. In this context, the ideal of equality

also feels somehow out oft

means being equal as a power and therefore being free from domination.

For about sixty-five ye£

This facet of equality has reverberated through American life. As we will

people by race, the people

see in the next chapter, some of its echoes are quite surprising.

providing "separate but e<

siana. law of 1890 require

through Louisiana "to pre

the white and colored ra.c<

aUy white activist Homer .

bought a first-class ticket fc

and sat in a whites-only cai

way to the Supreme Court.