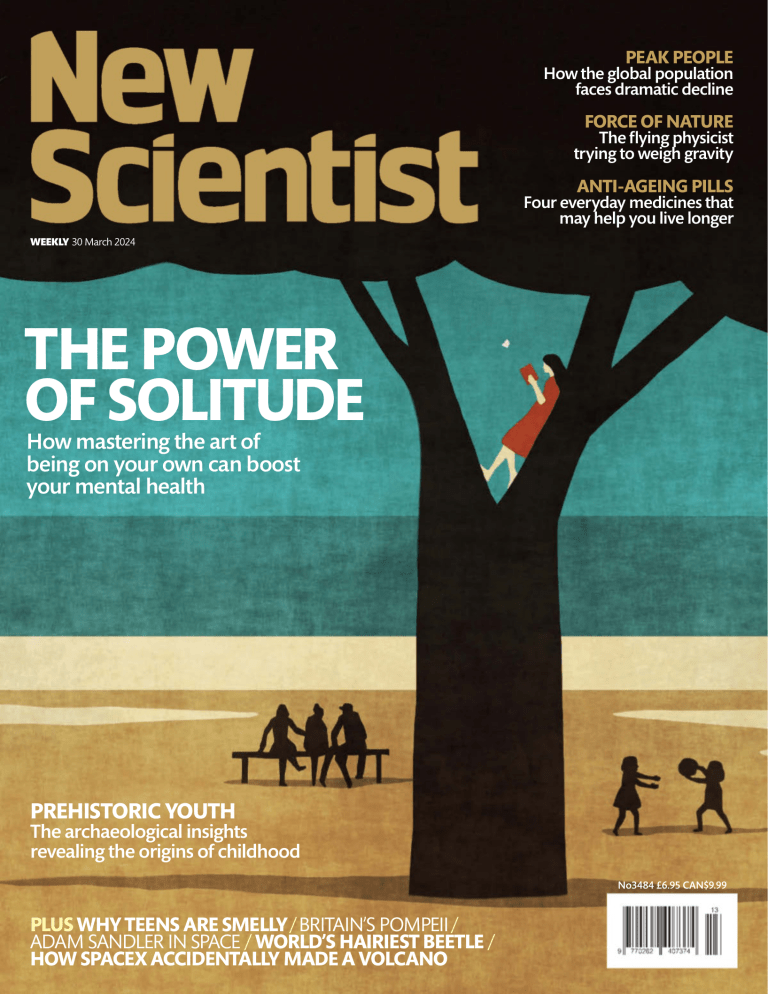

New Scientist Magazine: Population Decline, Gravity, Solitude

advertisement