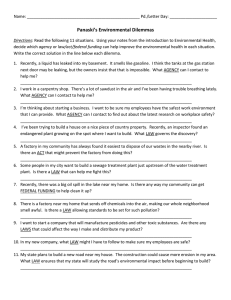

history arq (2016), 20.4, 345–356. © Cambridge University Press 2017 Why is the 1903 double glass curtain walled Steiff factory not considered part of modern architectural history, unlike the less modern 1911 Fagus Factory of Gropius and Meyer? Gropius and the Teddy Bear: a tale of two factories Brenda Vale and Robert Vale While based in Nuremburg and researching into toys and their relationship to architecture, we visited the Steiff Museum in the small German town of Giengen. Walking from the railway station, before you even reach the museum you pass the Steiff factory, at the front of which is a very modernlooking three-storey all-glass building with an almost flat roof. It has a double glass curtain wall, with a steel structure from which the glazing is hung, visible between the double glass panes. The most surprising aspect of this austerely functional building is that the glass on the end wall is dated 1903 [1]. We have been teaching architecture for a very long time, but had never come across this building before. For its date it seemed highly advanced, architecturally as well as thermally, with a double wall not unlike that of Emslie Morgan’s pioneering solar school in Wallesey, UK from the 1 early 1960s. Why had we never read about or been told about this early advanced factory building? Why is the Fagus factory by Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, which only has three-storey singleglazed windows, so often held up as the first modernist factory? We had to find out more. This article is based on what we discovered in our reading 2 of the handful of books and articles that mention the Steiff building and our revisits to both buildings. In 1903, when the steel and glass Steiff factory was built for the manufacture of teddy bears, Walter Gropius was twenty and beginning his study of architecture in Munich, some 111km away from Giengen by train, making a change at Ulm, just as is required today. Thus, although he may have been too old for teddy bears, this article was inspired by the fantasy that Gropius could have visited Giengen and seen the all-glass factory. Later Gropius had reason to buy a teddy bear as he had a daughter, Manon, born in 1916 following his unhappy marriage to 3 Alma Mahler in August the year before. Perhaps he bought his new daughter a fashionable Steiff bear, but probably not. In September 1916, as a cavalry officer, and a decorated war hero, Gropius was in the trenches at Verdun. He did send a picture by 4 Edvard Munch to Alma to note the birth. He first saw Manon when she was nearly six months old (a good time to receive a toy bear), describing her 5 as, ‘simply charming’. We know from their later correspondence that Gropius bought presents for Manon; Bauhaus furniture for her bedroom, a Bauhaus glass tea set, and a 400-year-old jade pendant 1 The Steiff factory, Giengen, Germany. 1 doi: 10.1017/S1359135516000518 history arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 345 346 arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 history when he forgot her eighteenth, and last, birthday.6 In 1935, after Alma and Gropius had divorced and Gropius had married Ise Frank, Manon died from polio, a tragedy that became the theme of Alban 7 Berg’s violin concerto Dem Andenken eines Engels. This article explores both the controversial history of the teddy bear and the less controversial history of the modernist factory in Germany, which is normally traced from Peter Behrens’s factory for AEG (1909) 8 to Gropius and Meyer’s factory for Fagus (1911) and beyond, omitting the 1903 double-skinned glass and steel Steiff building, still in use today for its original purpose of making stuffed toys. The bear factory The Steiff toy-making empire was created by a woman in a wheelchair. Margarete Steiff, another childhood polio victim like Manon, earned her living sewing women’s clothes until she made her first stuffed toy, which was an elephant-shaped pincushion. Children loved them and sales by her brother Fritz (Friedrich) at a local market led to the 1880 foundation of the company Margarete Steiff GmbH. By 1904 the firm was making 973,999 teddy 9 bears a year as well as nearly 2 million other toys. Moreover, these bears were made in a purposedesigned building. The 1903 Steiff factory [2] is not just an extraordinary building for its time, but one that is almost entirely absent from the history of modern architecture. With its steel frame, doubleskin curtain wall and glazed corners, it has all the elements of a modernist factory, except perhaps transparency, although this was a deliberate design choice. The strangeness of this 1903 all-glass factory comes into perspective when reading Budgett Meakin’s 1905 book on model factories.10 This work discusses lighting, ventilation, cleanliness, and gardens as important in the modern workplace and then suddenly praises the Templeton carpet factory in Glasgow, which was made, ‘a thing of beauty and an added attraction to the neighbourhood, by facing it with coloured brickwork after the design of the Doge’s Palace in Venice’, although also noting that this was also an advertisement for the firm with, ‘no need to label such a building with the 11 name of its owners’. The Steiffs already had a factory in Giengen, built by Margarete’s brother Fritz Steiff who took over his father’s building business, and in 1899 the factory was expanded with a glazed packing house linking the two buildings constructed earlier along 12 what is now Margarete Steiff Strasse. This linking building was designed with large arched floor-toceiling windows between masonry piers (currently partially filled in, as the factory buildings are now residential). Although contrasting with the rectangular windows-in-wall construction of the 1888 and 1890 buildings, it gave no foreshadowing of the new glass factory to come on the opposite side of the road. However, the popularity of the teddy bear demanded further expansion of the original factory. By this time, three of Margarete Steiff’s nephews (three of the six sons of Fritz, five of whom were eventually to join the Steiff company) had joined the firm, the first being Richard who arrived in 1897, and who was to design not just the original Steiff jointed bear but also the new factory. Richard may have been influenced by visits to London in 1897 where he saw the Crystal Palace (1851), and to Munich, which also had a glass 13 palace, the Glaspalast (1854), though neither had 2 Brenda Vale and Robert Vale Gropius and the Teddy Bear history arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 347 3a 2 1903 block, Steiff Fabrik, Giengen, designed by Richard Steiff. 3 Schwebebahn, Wuppertal, still running in 2015, compared with the Steiff steel frame. a double glass skin. Having studied business in the family firm he went to the Arts and Crafts School in Stuttgart. There he must also have seen the 1842–6 ‘Summerhouse with Living Quarters and Ornamental Plant Houses in the Moorish Style’ in Park Wilhelma, which consisted of a central 14 villa flanked by two cast iron glasshouses. The orangery, another type of highly glazed building, although originating in Italy was also known in Germany, with the first example constructed in 1614 in Heidelberg, as a permanent stone structure with a solid flat roof and many opening full-height 15 windows. However, rather than the all-glass building it may have been the speed of construction of the Crystal Palace and the Glaspalast in Munich, both of which were prefabricated (and both later destroyed by fire), that appealed to the business side of Richard Steiff. At the Crystal Palace the contractor agreed to enclose the eighteen acres (approx. 73,000m2) 16 covered by the building in twenty-two weeks. The building was only handed over in 1851 after nine months (forty weeks), still an amazing achievement, although exhibits had started to go in after six 17 months. The Glaspalast, which opened on 15 July 1854, also took nine months in total for design 18 and construction. Given it was possible to erect an all-glass building this quickly, in the face of the 3b profits that could be made from the unprecedented demand for teddy bears, a quickly-erected glass structure would have seemed logical. The idea may have come from Friedrich Steiff (Margarete and Fritz’s father) who went to the 1893 19 World’s Fair in Chicago. There the Horticultural 20 Building featured a glass dome 180ft in diameter. More influential on the rectangular structure of the new factory could have been the framed structures in Chicago such as the 1885 Home 21 Insurance Building and the first building with a skeleton steel structure, the ten-storey Rand McNally Building of 1889, by Burnham and Root 22 (demolished 1911). The frame of the latter was of riveted rolled steel beams and columns assembled 23 from steel members used in bridge construction. Gropius and the Teddy Bear Brenda Vale and Robert Vale 348 arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 history Steel construction was also being used in Germany at that time, at least for engineering structures, with, for example, the first section of the Wuppertal Schwebebahn opened in 1901 after construction started in 1898. Designed by the engineer Eugene Langen, this ‘suspension railway’ used built-up steel supports for its linear track over the River Wupper and large riveted steel portal frames, very like the frames at either end of the Steiff building, where the track ran above 24 the centre of the streets [3]. Within this milieu it is not surprising that a steel structure was used for the 1903 three-storey all-glass Steiff factory. In 1902 Margarete Steiff wrote to another nephew, Paul, then in the US, that, ‘Richard envisages a building made of iron and glass [...] – whether it will 25 work only time will tell’, but her expertise was in sewing, and not in building. A glass building would also give plenty of daylight. Michael Stratton states that early examples of daylight factories in America, which Paul Steiff might have seen, were a development of the mills of the nineteenth-century industrial revolution, and typically had a concrete frame with more glass (as steel-framed windows) than solid in the elevation. 26 Reyner Banham suggests the real revolution in early American factories was from 1902–6, when the reinforced concrete frame replaced the former 27 brick pier construction. What Paul Steiff may have taken from his American visit was the importance of designing for daylight and what Banham describes as the American ‘flat-topped profile’ of its multi28 storey industrial buildings. These contrasted with the typical European industrial buildings of several 29 storeys with steeply pitched tiled roofs. The Steiff factory has a slightly sloping roof but, unlike the American examples, there is no parapet to hide it. 30 Raymond McGrath and Albert Frost claim the glass wall originated with the work of Joseph Paxton and, ‘was soon exploited in the iron and glass warehouse in Jamaica Street, Glasgow, 1856, and by the end of the century was already fully realised in the four-storied [sic] plate-glass facade of the Tietz Department Store in Berlin (1896).’ Lost in the Second World War, this building was completed in 1900 and featured flamboyant Baroque stonework framing the two street-facing glass walls making the displays inside visible to those outside, the whole also being roofed with a glass barrel vault. Claimed as the first curtain facade (Vorhangfassad) in Germany each iron-framed plate glass wall was 26m wide 31 by 17.5m high. Polished plate glass at this time was an expensive product. Of even more relevance to the theme of this article, the family history of Tietz describes the creation of this building as a collaboration of German and American engineers who made the calculations around which the 32 architect Bernhard Sehring planned the building. The same point is made by the operators of the contemporary Wuppertal Schwebebahn: At the end of the 19th century, steel engineering was still a relatively new field of construction. Only after the creation of the first major steel structures, including the Wuppertal Suspension Railway, were the Brenda Vale and Robert Vale Gropius and the Teddy Bear calculations actually tested and confirmed.33 This suggests an alternative history of the ‘new’ materials of iron, glass, and concrete, that is, the history of the engineering calculations that allowed these old materials to be used in new ways, within which the Steiff factory could have a place. The modern movement is perhaps less about new materials than about new calculations. The Crystal Palace of 1851 was roofed with sheet glass blown as cylinders 10 inches diameter and 49 inches long and 1/13th inch thick and then 34 flattened into sheets. This was installed using putty. According to the planning application of 20 February 1903, the interior glass of the Steiff factory was to be frosted glass with the outer skin of 35 clear glass. However the Steiff factory as it stands is glazed with cast glass, since it is rough on both sides. This rough rolled plate glass was made by pouring the molten material on to a table, and the glass was then rolled into a sheet. A textured surface to the table produced rough rolled plate glass which in 1875, Percy Major Smith described as suitable, ‘where coarse, strong, translucent material is required. The light is admitted without scorching or glare’. Smith deemed such glass appropriate for 36 the windows of railway stations and factories. Whether German orangeries and monorails, the English Crystal Palace or American industrial buildings provided inspiration, the Steiff factory goes beyond all these prototypes in being not just all-glass but also double-glass. This principle of double-glazing was already familiar in German residential buildings, with removable glazed wooden frames being added to the interior of windows at the onset of winter. This would give a gap between the panes that could vary from 100mm to 300mm. Writing about the life in 1835 of the prosperous Buddenbrooks family, Thomas Mann describes the double windows being installed in the house by mid-October to keep Madame 37 Buddenbrooks Senior warm. The oldest such double windows in Germany, dating to 1695, are in the Upper Castle in Pfingen in Ulm, now converted 38 to apartments. Even given this German domestic tradition of double windows it was not just that the Steiff factory had double glass walls, but the fact the glass was hung from the steel frame located between the two glass skins that made Steiff’s design so unusual for its date. The Steiff curtain wall The double curtain wall designed by Richard Steiff is all-glass to allow the levels of natural light needed inside the factory for the fine work of making teddy bears, much of which is done by hand. The wall is a true curtain, being non-loadbearing and tied back to the steel frame, which is located between the two glass skins, so that as at the later Fagus factory the corners of the building are glass, although at Steiff the steel frame is visible in the translucent corners. Opening windows occur at intervals in the double glass facade. The external glass has a 39 rippled texture (Kathedralglas) to reduce glare and prevent anyone seeing inside, thus protecting the history Steiff process from being viewed by competitors. A low-pressure steam heating system was installed to maintain temperatures in winter. In summer the intention had been to cool the building using cross ventilation through the opening windows in 40 the facade, combined with use of internal blinds but in the event, ventilator fans were also installed, together with the pragmatic gardener’s trick of whitewashing the glass walls in summer to avoid 41 excessive solar gain. At this early stage, trying to achieve an acceptable indoor environment was still a question of trial and error. The thermal performance of the 1911 single-glazed Fagus factory was also unsatisfactory, with office workers near the windows having to wear extra clothes and thermal underwear in winter because of the cold draughts. Fagus also suffered from over-heating in summer even with the later installation of an air conditioning 42 system. This is not surprising given its east-southeast orientation which would cause it to heat up quickly on a summer morning. Rust was an issue for some of the Fagus windows from as early as 43 1919 but this appears not to have been a problem at Steiff, where 80% of the glass is original, with 44 panes being replaced as necessary over the years. In fact, the 1903 building served its purpose so well that further buildings with double glass curtain walls were constructed on the Steiff site, albeit with timber rather than steel frames, and by 1910 just over 1.5 hectares of floor area were enclosed by 45 double glass walls. The wall of the Steiff factory is completely different from the ‘mur neutralisant’ of Le Corbusier, which first appeared in the Villa Schwob (1912) at 46 La Chaux de Fonds. Le Corbusier is often credited with being an early exponent of the use of double 47 glass walls. At the Villa Schwob the two-storey floor to ceiling glazing around the front door, like other large windows in the villa, was double with heating pipes between the glass skins to prevent down draughts from the otherwise cold glass. Le Corbusier went on to use the same technique in his glass curtain-walled Cité de Refuge (1929–33) in Paris, which was sealed, with the intention of passing warm air into the cavity between the glass skins. In fact architects seem to have had this passion for warming the outside (in this heated cavity situation the heat will flow to the colder exterior rather than to the warmer interior of the building), as Alvar Aalto also used heating elements in the double windows of his Paimio Sanatorium (1929–33), to warm the incoming fresh air which passed through a series of baffles, although here 48 the windows were not sealed. The fact that the Steiff factory significantly predates these much more famous buildings is perhaps a tribute to the willingness of the architectural profession to ignore buildings that work, in favour of apparently more delightful failures, like the Cité de Refuge where the double glass system was not built, with subsequent overheating and the need for the addition of 49 opening windows and brise-soleils. One of the few books to mention the Steiff factory arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 349 claims it as the first double-skin curtain walled 50 building. This now fashionable technique has been hailed as a good way for modern corporate 51 architecture to appear to be ‘green’. However, it is not just its ‘green’ credentials that should have earned Steiff a place in architectural history but rather the fact that it is a true all-glass box. Instead, it is the 1911 Fagus factory with its large windows that is seen as the first modern factory. The Fagus factory The Fagus factory (which made shoe lasts from beech wood, hence the company name which is the Latin name for the beech tree) has been described as one of the most important early 52 modernist buildings and in 2011 was listed as a 53 UNESCO World Heritage site. It is also a building 54 that helped to establish Gropius, the architect, although it is perhaps fairer to say that Gropius helped himself to fame through the Fagus factory, becoming an expert in industrial building 55 following the Fagus commission. His lecture of 1911 entitled Monumentale Kunst und Industriebau (Monumental Art and Industrial Building) a typewritten version of which is in the Bauhaus archives, deals not just with German examples of factories and railway stations, but also with bridges from the UK 56 and grain silos from North and South America. One of Gropius’s first commissions was the 4 4 The ‘Gropius knot’, which a medieval carpenter would recognise as a dragon beam, is visible through the corner glazing of the 1911 block. Gropius and the Teddy Bear Brenda Vale and Robert Vale 350 arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 history 5 1905–6 Kornspeicher (granary) at his uncle’s farm although this building has a pitched roof and is 57 more picturesque than monumental. Gropius also claimed to be the first architect to use a real 58 curtain wall at the Fagus factory. The Fagus factory however, is better considered as a series of threestorey windows between brick piers. The brick piers slope inwards slightly from bottom to top and the windows have alternating glass and solid metal panels corresponding to the floor slabs. This arrangement is the opposite of the long street elevation of the earlier AEG factory by Behrens, where the windows slope inwards towards the top and the piers in between are vertical. Structurally the Fagus building is similar to a nineteenth-century mill, built of brick with iron 59 beams between the brick piers and the rear wall even though American factories had already started using reinforced concrete frames to replace brick 60 piers in 1902. Gropius’s famous glass corner is supported by a version of a dragon beam, such as might be found in a mediaeval timber building, but 61 in steel and known as the ‘Gropius knot’ [4]. What is ‘modern’ about the Fagus factory is much less the way it is constructed but rather its appearance, especially the glazed corners [5]. However, the legend is that the Fagus factory is a ‘skeleton frame 62 structure with glazed curtain walls’, or, ‘the first factory featuring a curtain wall: from a skeletal frame the architects hung a glass facade which even 63 extended to transparent corners’ [5]. The glass factory This article is not the first attempt to give Richard Steiff’s building its true place in architectural history. In 1932 a brief article described it as one of the best examples of functional architecture Brenda Vale and Robert Vale Gropius and the Teddy Bear to emerge in the last thirty years, though most of the text discussed the problems of obtaining building consent for such an advanced building, especially as the Building Inspector believed an 64 all-glass building would make people blind. The Steiff factory was also mentioned briefly in the 1932 book Der Industriebau by Hermann 65 Maier-Leibnitz. In a discussion of glazed walls and day lighting, three wall sections are shown, the normal wall with window, the double glass Steiff factory and the single-glazed Fagus factory, but whereas the Fagus factory is illustrated and 66 attributed to Walter Gropius, the Steiff factory becomes a footnote where it is described as probably the first glass building for manufacturing 67 purposes. This dismissive footnote also failed to remark on the fact that this revolutionary building was constructed from start to finish in 68 just over six months. David Yeoman’s history of the development of the curtain wall also ignores Steiff, though the Fagus factory is mentioned, and he attributes the first 100% glazed wall (single glass) to the 1917 seven-storey Hallidie Building in 69 San Francisco by Willis Polk. It seems the truly innovative Steiff factory has remained more or less unknown in contrast to the aesthetically driven design of the Fagus factory. For example, Raymond McGrath and Albert 70 Frost consider Paxton to be the originator of the transparent wall, and Gropius and Meyer at Fagus the first to apply it to industry. The architectural history of the German, modern, glazed factory usually begins with Behrens’s 1909 AEG Turbinenhalle in Berlin [6]. Here the single-glazed end wall onto the main street is almost overwhelmed by the mass of masonry in the corner piers, which are there for effect rather than support. The long flanking wall history arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 351 5 Fagus factory block by Gropius and Meyer, 1911. 6 AEG Turbinenhalle by Peter Behrens, 1909. 7AEG Powerhouse by Franz Schwechten, 1900. 6 7 has large glass windows that slope between the supports. Next in time is the 1911 Fagus factory by Gropius and Meyer, a restyling of an earlier design by another architect, Eduard Werner, which had the same three-storey windows, although with 71 arched heads. The 1914 Model Factory for the Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne by Gropius and Meyer comes closest to the glass skinned steel frame ideal achieved by Steiff eleven years earlier, but again was only single-glazed. Gropius only achieved his continuous curtain wall in the Bauhaus of 1926, 72 which might be called a factory for learning. Among these cornerstones of architectural history, the Turbinenhalle is a monumental shed with a large glazed opening in the end, looking more like the west end of a gothic cathedral than a glass box. Although Nikolaus Pevsner suggests that the building is the first to synthesise, ‘the imaginative 73 possibilities of industrial architecture’, it echoes the facade of an earlier building for AEG, the 1900 powerhouse by Franz Schwechten [7], an architect whose work was looked down upon by the new 74 generation, of which Behrens was part. Behrens’ factory was famously described by the art critic Karl Scheffler as a ‘Kathedrale der Arbeit’ 75 (‘cathedral of labour’), a description referenced by Gropius in the typescript of his lecture on industrial buildings: ‘Scheffler correctly calls the 76 Turbine hall a cathedral of labour.’ Gropius famously worked for a time in Behrens’s office and recalled debating with Behrens that both the front and side facades of the Turbinenhalle were manipulated for aesthetic rather than true 77 structural reasons. However, when it came to the Fagus factory main building Gropius was somewhat less critical of himself, stating in relation to the windows that the creative spark of the artist goes .78 beyond logic and reason These same windows he referred to as a curtain wall, noting that although this had become central to modern architecture by the middle of the twentieth century, it would be hard to imagine the difficulties of getting it past 79 the ‘Baupolizei 1911’. No such difficulties seem to have stopped Steiff with his double-glazed curtain wall six years earlier in spite of his troubles with the Building Inspector. Gropius and the Teddy Bear Brenda Vale and Robert Vale 352 arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 history A place in architectural history That the Fagus factory became the modernist icon, and not the Steiff building, may have more to do with the evolving history of modern architecture than the merits of either building, despite the fact that the latter has been described as, ‘well 80 in advance of Gropius’s famous Fagus-Werke’. A 1924 article in the Architectural Review is somewhat critical of Fagus because of the brick fascia being apparently supported on, ‘fragile glass and spidery 81 muntins’. Neither building was one of the three European factories visited by Frank Yerbury for his 82 1928 book Modern European Buildings. However, a year later Henry Russell Hitchcock saw Gropius as seeking, ‘the direct expression of engineering’, in 83 his industrial buildings. In his view, the success of the Fagus factory was only surpassed by the 1928 van Nelle factory in Rotterdam by Van der Vlugt and 84 Brinkman. By January 1936, Pevsner, in a reported lecture, describes Gropius as, ‘one of the originators 85 of the modern movement in architecture’, and this view became entrenched in the book Pioneers of Modern Design: from William Morris to Walter Gropius, published later the same year. Pevsner also states: There was Gropius himself, one of the foremost architects in the world, who, in 1911, designed a building which everybody today would from its 86 appearance mis-date as 1930 or 1935. Poor Meyer is never credited in the lecture and only appears as architect with Gropius under the image of the Fagus factory in the book, but, unlike Gropius, Meyer never became the director 87 of the Bauhaus. The influence of this hotbed of modernism on cementing its director’s reputation and his buildings should not be underestimated. Nor had Meyer been the author, as Gropius had, of the 1935 book The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, which begins with a photograph of the transparent 88 corner of the 1911 Fagus factory building. The following year Walter Curt Behrendt saw the new utilitarian building types that came with industrialisation (factories, offices, department stores) as creating new types of building based on, 89 ‘a strict rationality [...] and strong technical logic’. For him, Gropius was part of this search for new 90 building types. The current exhibition at the Fagus factory (October 2016) refers, in a caption to one of the display panels, to how Gropius and his client Carl Benscheidt realised the importance of what they had achieved: Das von ihnen gemeinsam geschaffene, einmalige Werk der Industriekultur, dessen bedeutung von Jahr zu Jahr klarer erkannt wurde (the unique work of industrial culture they jointly created, whose significance became recognized more clearly from year to year). It seems that just as Gropius and Benschiedt appreciated their achievement, so would the architectural historians and critics who came after them. Given all this, it is unsurprising that the Fagus factory became an icon, to the extent that Banham can claim that modern architecture visually begins in 1911 with ‘Gropius’s Fagus factory’ 91 and ends with the glass skyscraper. Brenda Vale and Robert Vale Gropius and the Teddy Bear The teddy bear The Steiff factory was built to make teddy bears, whose history is at least as contested as that of the modern factory. The ‘teddy’ appendage comes from President Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt after the president had refused to shoot an old bear that was a ‘plant’ so that his 1902 bear hunt should be a success, an event popularised by a cartoon in the 92 press. In fact Roosevelt asked one of his hunting guides to dispatch the unconscious bear with a knife so the initial newspaper cartoon was well 93 off the mark. The American version of the teddy bear story goes that after the cartoon appeared, Rose Michtom, who with her husband ran a sweet shop (or candy store) in Brooklyn, overnight sewed a velvet bear with jointed arms and legs (the original is now in the Smithsonian collection) and placed it in the shop window the next day labelled ‘Teddy’s bear’. Someone immediately offered to buy the bear and the Michtoms eventually gave up shopkeeping. By 1903, they had founded the Ideal Toy Company selling teddy bears, having obtained 94 Roosevelt’s permission to use his name. By 1908 so many teddy bears had been sold it was feared they would replace dolls and destroy the maternal instincts of the next female generation in the 95 United States. However, if you are German, the first plush bear (plush is a fabric that has a pile) with moveable arms and legs was invented in 1902 by Richard Steiff [8]. The purpose behind exploring the history of the teddy bear in an article about a building is to show how easily a set of what might be assumed to be clear historical events can be looked at from a number of different viewpoints. In her 1966 book A History of Toys, Antonia Fraser states that the teddy bear is of American origin but that large numbers of teddy bears were made in Germany in the same 96 period while Marguerite and Kenneth Fawdry noted that stuffed toy bears with all four paws on 97 the ground had been around for over a century. Robert Southey had published The Story of the Three Bears in 1837 which probably served to popularise 98 bears in general. However, the Fawdrys are noncommittal about where the idea for the teddy bear came from, acknowledging the Michtoms gaining Presidential permission to call their toy a ‘Teddy’ bear and the fact that around the same time teddy bears were produced in quantity at the Steiff factory. Pauline Cockrill also notes that toy bears had been around in Germany before the jointed teddy bear, both as clockwork automaton figures and as soft toys standing on all fours, some of 99 which, made by Steiff, were mounted on wheels. She goes on to suggest that jointed plush bears were made at the same time in both America and Germany. Gwen White claims general agreement 100 that the first teddy bears were American, which is in contrast to Deborah Jaffe who states that Steiff quickly responded to the cartoon of President Roosevelt allegedly sparing the bear with their jointed soft bear that could sit and made of mohair 101 plush. Nicholas Whittaker is clear that stuffed bears predated the President’s refusal to shoot the history arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 353 8 elderly bear but that this incident gave a massive 102 boost to their popularity in the nursery. Steiff were certainly making bears in the nineteenth century, with plush bears offered first, in four colours and two heights with, according to their 1892 catalogue, ‘soft stuffing for small children’ (weichgestoppt für kleine Kinder) and ‘with voice’ (mit Stimme) for 1 Mark 20 Pfennigs extra, but these 103 early bears were not jointed. Whittaker further muddies the waters by referring to another myth. This was the love of Edward VII, who reigned from 1901 to 1910 for koala ‘bears’ (the koala being a marsupial rather than a formal member of the bear family) in London Zoo, which gave rise to their popularity 104 and name, as his own nickname was ‘Teddy’. The Fawdrys also claim the song Teddy Bears’ Picnic as 105 English although the tune comes from The Teddy Bears Two-step, which was composed in 1907 in 106 America by John Walter Bratton. David Veart sums it up by simply saying there are two histories for the bear invented in 1902, one American and one 107 German. There might also be two histories for the Modernist glass factory, one familiar and German, and one equally German but overlooked. Conclusion It seems the history of architecture can be constructed from the meanings ascribed to buildings. Richard Steiff’s factory was designed to give sufficient daylight for easy construction of teddy bears. Fast work means more profit and the glass was there to make the task easy. The 8 Souvenirs – the 2016 Steiff Museum bear and a Fagus beech wood last for a child’s shoe. functional reason for using obscured glass might have been to ensure that workers could not see out, which could be a distraction, or that competitors could not see in to steal trade secrets. It might equally have been a response to produce diffused light and avoid glare, or because obscured glass 108 was a cheaper product. Moreover, whereas the Fagus factory has undergone a comprehensive refurbishment including complete replacement of the windows (the new windows are double-glazed), the Steiff factory only needed a new roof in 2008, because the original had blown off in a storm. Today, the glass is 80% original, and when the top two floors were converted to offices (the ground floor is still used for toy-making), the wood flooring 109 was taken up, sanded, and replaced. The advanced technology of the Steiff factory was employed to create an effective factory, whereas when Gropius and Meyer designed the Fagus factory – technically only a restyled Victorian mill – it was intended to convey what Modernism was about as much as to provide office accommodation and associated work spaces for the shoe last factory Ironically, the construction of the more functionally-designed Steiff building has been ignored in the subsequent construction of the history of functionalism. The Steiff factory could have been ignored because it was not designed by an architect, Gropius and the Teddy Bear Brenda Vale and Robert Vale 354 arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 history but then nor was the Crystal Palace, which was designed by a gardener. In general the history of architecture seems to have more respect for engineers than gardeners, citing the bridges of 110 the Swiss engineer Robert Maillart and the work 111 of Owen Williams. However, these are engineers who engage in serious civil engineering rather than stuffed-toy design. The Steiff factory could have been ignored because Giengen is a very small town on a railway branch line, but then Alfeld, where the Fagus factory still stands, is hardly on many tourist destinations unless they are making a pilgrimage to Gropius (although the factory was always intended to be visible to those passing 112 by train). As an archetypal glass box, the Steiff factory seems to fit and indeed to predate, so many of the tenets of Modernism—it is functional, made of steel and glass, and devoid of ornament. Despite a number of attempts to bring it to public notice (and this is just one more) it remains obscure. The book and article of 1932 have been mentioned. In the 1970s an article was published in Bauen und Wohnen describing the building and concluding its anonymity was due not so much to the fact that it was situated far from the centres of modern building but that it did not have a famous name 113 attached to it. This is fair comment except that the factory does have a famous name attached to it, but a name better known for teddy bears and other plush toys, as well as the Knopf im Ohr (Button in Ear) brand, which was a 1904 invention of 114 Richard Steiff’s brother Franz. The famous name is the user of the building rather than its designer. Toys produced by Gropius’s Bauhaus are a long way from the comfort of a well-loved bear, being mostly wooden, geometric, and painted in primary 115 colours, such as Alma Buscher’s Bauspiel ‘Schiff’ and her Throw Dolls made of wooden beads, bast fibre bodies and chenille clothing, which were meant to be cuddled (in a stringy sort of way) as 116 well as thrown, but were more cuddly than the Notes 1. Peter Manning, ‘St. Georges School Wallasey: an Evaluation of a Solar Heated Building’, Architect’s Journal, 149:6 (1969), 1715–21. 2. A book in German on the Steiff Factory is due for publication late in 2016: Bernhard Niethammer and Anke Fissabre, Die Steiff Spielwarenfabrik in Giengen/Brenz (Aachen: Geymüller, Verlag für Architektur). 3. Francoise Giroud, Alma Mahler or the Art of Being Loved (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 113. 4. Ibid., p. 118. 5. Reginald Isaacs, Gropius: An Illustrated Biography of the Creator of the Bauhaus (Boston; Toronto; London: Bullfinch Press, 1991), p. 53. Brenda Vale and Robert Vale Gropius and the Teddy Bear peg stick figures of Margaretha Reichard.117 Perhaps an association with being cuddly and comforting just does not go with Modernism. Maybe this article is no more than an illustration of how history is constructed and how we are taught what we should regard as important buildings, and the important architects who designed them (and Gropius was an excellent self-publicist), rather than just using our eyes. The problem comes in that we tend to go and look at the buildings we learn or read about. We found the Steiff factory by accident and feel it deserves much wider consideration. This is not the only building that fails to make mainstream architectural history. Good, and even great, architecture has to be about what we see for ourselves and not just what we are told is good. The Steiff factory is a building where performance was considered alongside aesthetics. Whilst Annemarie Jaeggi admits the Steiff factory with its double translucent glass skin was more functional thermally and in terms of lack of glare than Fagus she sees it as, ‘the work of an engineer, not an architect/artist, whereas the Fagus building 118 was […] rooted […] in a profound theory’. Jaeggi accepts that the Fagus factory did not perform well, but the profound irony is that this does not seem to detract from its perceived importance as she finds that a less functional building designed according to a theory of functionalism is of greater significance than a building that is actually functional. Whatever the reason, Steiff’s remarkable glass factory architecturally languishes in an unknown backwater. It is tempting to insert one extra word into Banham’s statement: Down to about 1940 when authors tend to emphasise the pioneering use of ‘new’ materials like cast iron, glass, steel, and concrete, [almost] any engineer or architect who availed himself of any of these at an early enough date, however dim or dubious the actual work done with it, was apparently assured of an 119 honoured place. 6. James Reidel, ‘Walter Gropius: Letters to an Angel, 1927–35’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 691 (2010), 88–107. 7. Giroud, Alma Mahler or the Art of Being Loved, pp. 140–1. 8. 1911 is the date of the Gropius and Mayer block of offices facing the railway. The workroom was built to the plans of Eduard Werner in 1911/12 and extended in 1914, in: <http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/ nominations/1368.pdf> [accessed 10 November 2016]. 9. Steiff Firmenhistorie: <http://www. steiff.com/de-de/fascination-steiff/ history/> [accessed 10 November 2015]. 10. Budgett Meakin, Model Factories and Villages (London: T. Fisher and Unwin, 1905). 11. Ibid., pp. 80–1. 12. Günther Pfeiffer, 125 Years: Steiff Company History (Königswinter: Heel, 2005), pp. 66–7. 13. Ibid., pp. 155–6. 14. Stefan Koppelkamm, Glasshouses and Wintergardens of the Nineteenth Century (London: Granada Publishing Ltd, 1981), pp. 64–7. 15. John Hix, The Glass House (London: Phaidon, 1974), p. 10. 16. Christopher Hobhouse, 1851 and the Crystal Palace (London: John Murray, 1950), p. 43. 17. Charles H. Gibbs-Smith, The Great Exhibition of 1851 (London: HMSO, 1950), pp. 13–15. 18. Klaus Bäumler, ‘Glaspalast, München’, in Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (2012) <http://www. historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/ history artikel/artikel_44720> [accessed 10 November 2015]. 19. H. P. C. Weidner, ‘Der Glaspalast 1903’, Bauen und Wohnen, 7 (1970), 229–32. 20. Julie K. Rose, Tour the Fair (1996) <http://xroads.virginia. edu/~ma96/wce/tour2.html> [accessed 12 March 2016]. 21. Leslie Thomas, Chicago Skyscrapers, 1871–1934 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2013), pp. 44–7. 22. Joseph J. Korom, The American Skyscraper, 1850–1940: a Celebration of Height (Boston: Branden Books, 2008), pp. 120–1. 23. William A. Starret, Skyscrapers and the Men who Build Them (New York; London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1928), p. 34. 24. Monorails of Europe: Wuppertal, Germany: <http://www.monorails. org/tMspages/Wuprtal.html> [accessed 9 December 2015]. 25. Pfeiffer, 125 Years, p. 156. 26. Michael Stratton, Industrial Buildings: Conservation and Regeneration (London: E. and F. N. Spon, 2000), p. 35. 27. Reyner Banham, A Concrete Atlantis (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1986), p. 56. 28. Ibid., p. 39. 29. James M. Richards, The Functional Tradition (London: The Architectural Press, 1958). 30. Raymond McGrath and Albert C. Frost, Glass Architecture and Decoration (London: Architectural Press, 1937), pp. 158–9. 31. Alarich Rooch, ‘Wetheim, Tietz und das KaDeWe in Berlin’, in The Berlin Department Store, ed. by Godela Weiss-Sussex and Ulrike Zitzlsperger (Pieterlen and Bern: Peter Lang, 2013), p. 191. 32. Georg Tietz, Hermann Tietz: Geschichte einer Familie und ihrer Warenhäuser (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1965), pp. 60–1. 33. Technology: <https://www. schwebebahn.de/2/historytechnology/suspension/> [accessed 23 October 2016]. 34. McGrath and Frost, Glass Architecture and Decoration, p. 123. 35. Weidner, ‘Der Glaspalast 1903’, fn. 6. 36. Percy Major Smith, Rivington’s Building Construction (London: Longmans, 1904 [orig. pub. 1875]), p. 426. 37. Thomas Mann, Buddenbrooks: Verfall einer Familie (1909) <http://www.gutenberg.org/ files/34811/34811-h/34811-h.htm> [accessed 12 June 2015]. 38. Mila Schrader, Fenster, Glas und Beschläge als historisches Baumaterial – Ein Materialleitfaden und Ratgeber (Suderberg: anderweit Verlag, 2001), p. 68. 39. Weidner, ‘Der Glaspalast 1903’. 40. Scott Murray, Translucent Building Skins (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), p. 53. 41. Pfeiffer, 125 Years, p. 159. 42. Jürgen Götz, ‘Maintaining Fagus’, in Fagus: Industrial Culture from Werkbund to Bauhaus, ed. by Annemarie Jaeggi (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000), p. 139. 43. Ibid., pp. 136–8. 44. Simone Pürckhauer, personal communication, 17 October 2016. 45. Pfeiffer, 125 Years, p. 158. 46. Reyner Banham, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (London: Architectural Press, 1969), pp. 158–9. 47. William W. Braham, ‘Active Glass Walls: A Typological and Historical Account’, paper presented at the AIA Convention (2005) <http://repository. upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1020&context=arch_ papers> [accessed 3 March 2016]. 48. Colin Porteous, The New EcoArchitecture (London: Spon, 2002), p. 61. 49. Banham, Well-Tempered Environment, pp. 156–7; Porteous, The New Eco-Architecture, p. 62. 50. Murray, Translucent Building Skins, pp. 50–6. 51. Harris Poirazis, Double Skin Facades: a Literature Review (Lund: Department of Architecture and Built Environment, Division of Energy and Building Design, Lund University, Lund Institute of Technology, 2006). 52. Gilbert Lupfer and Paul Sigel, Gropius (Köln: Taschen, 2004), p. 17. 53. Fagus factory in Alfeld: <http://whc. unesco.org/en/list/1368> [accessed 12 March 2015]. 54. Lupfer and Sigel, Gropius, p. 23. 55. Annemarie Jaeggi, Fagus: Industrial Culture from Werkbund to Bauhaus (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000), pp. 44–5. 56. Harmut Probst and Christian Schädlich, Walter Gropius Band 3: Ausgewählte Schriften (Berlin: VEB Verlag for Bauwesen, 1988), p. 28. 57. Reginald Isaacs, Gropius: an Illustrated Biography of the Creator of the Bauhaus (Boston; Toronto; London: Bullfinch Press/Little, Brown and Co. Inc., 1991), p. 14. 58. Anke Fissabre and Bernhard Niethammer, ‘The Invention of the Glazed Curtain Wall in 1903— the Steiff Toy factory’, Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History, Cottbus (2009); Jaeggi, Fagus, p. 29. 59. Jaeggi, Fagus, p. 29. 60. Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, p. 56. 61. Jaeggi, Fagus, pp. 28–9. 62. Werner Durth and Roland May, arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 355 ‘Schinkel’s Order: Rationalist Tendencies in German Architecture’, Architectural Design, 77 (2007), 44–9. 63. Magdalena Droste, Bauhaus, 1919–1933 (Köln: Taschen, 2007), p. 14. 64. Max Cetto, ‘Eine Fabrik von 1903’, in die neue stadt, Juli (1932), p. 88. 65. Hermann Maier-Leibnitz, Der Industriebau (Berlin: SpringerVerlag GmbH, 1932), pp. 256–7. 66. ‘Entwurf: W. Gropius’. 67. ‘Spielwarenfabrik M. Steiff, Giengen a. Br., erbaut 1904 [sic] und damit wohl das erste Glashaus für Fabrikationszwecke’. 68. Pfeiffer, 125 Years, p. 82. 69. David Yeomans, ‘The Pre-History of the Curtain Wall’, Construction History, 14 (1998), 59–82. 70. McGrath and Frost, Glass Architecture and Decoration, pp. 158–9. 71. Jaeggi, Fagus, pp. 16–21. 72. Nikolaus Pevsner, Pioneers of Modern Design (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd, 1968 [orig. pub. 1936]), pp. 211–17. 73. Ibid., p. 204. 74. Alan Windsor, Peter Behrens: Architect and Designer 1868–1940 (London: Architectural Press, 1981), p. 83. 75. Karl Scheffler, Die Architektur der Großstadt (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer Verlag, 1913), p. 47. 76. ‘Diese Halle konnte Scheffler mit gutem Recht eine Kathedrale der Arbeit nennen’, in Walter Gropius Band 3, ed. by Probst and Schadlich, p. 48. 77. Helmut Weber, Walter Gropius und das Faguswerk (München: Verlag D. W. Callwey, 1961), p. 23. 78. ‘Der schöpferische Funke des Künstlers geht über Logik und Vernunft hinaus’, Ibid., p. 66. 79. Ibid., p. 60. 80. Dennis J. de Witt and Elizabeth R. de Witt, Modern Architecture in Europe (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), p. 98. 81. Hermann G. Scheffauer, ‘The Work of Walter Gropius’, Architectural Review, 56 (1924), 50–4. 82. Frank Yerbury, Modern European Buildings (London: Gollancz, 1928). 83. Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Modern Architecture (New York: Payson and Clark, 1929), p. 187. 84. Ibid., pp. 136–57. 85. Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Post-War Tendencies in German Art Schools’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 84:4339 (1936), 247–62. 86. Ibid. 87. Pevsner, Pioneers of Modern Design, p. 213. 88. Walter Gropius, The New Architecture and the Bauhaus (London: Faber and Faber, 1965 [orig pub. 1935]), p. 18. Gropius and the Teddy Bear Brenda Vale and Robert Vale 356 arq . vol 20 . no 4 . 2016 history 89. Walter C. Behrendt, Modern Building: its Nature, Problems and Forms (New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1937), p. 97. 90. Ibid., p. 156. 91. Reyner Banham, Age of the Masters (London: Architectural Press, 1975), p. 16. 92. Real Teddy Bear Story: <http://www. theodoreroosevelt.org/site/c. elKSIdOWIiJ8H/b.8684621/k.6632/ Real_Teddy_Bear_Story.htm> [accessed 11 March 2015]. 93. Teddy Bear: <http:// americanhistory.si.edu/press/factsheets/teddy-bear> [accessed 14 October 2016]. 94. Rose and Morris Michtom: <http:// www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ jsource/biography/Michtoms. html> [accessed 12 March 2015]. 95. Teddy Bear: <http:// americanhistory.si.edu/collections/ search/object/nmah_491375> [accessed 12 March 2015]. 96. Antonia Fraser, A History of Toys (London: Spring Books, 1966), p. 183. 97. Kenneth Fawdry and Marguerite Fawdry, Pollock’s History of English Dolls and Toys (London: Ernest Benn Ltd, 1979), p. 86. 98. Robert Southey, The Story of the Three Bears, 2nd edn (1839) <https:// en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Story_ of_the_Three_Bears> [accessed 10 March 2016]. 99. Pauline Cockrill, The Ultimate Teddy Bear Book (London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd, 1991), p. 12. 100. Gwen White, Antique Toys and their Background (London: Batsford, 1971), p. 160. 101. Deborah Jaffe, The History of Toys: From Spinning Tops to Robots (Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd, 2006), pp. 150–1. Brenda Vale and Robert Vale Gropius and the Teddy Bear 102. Nicholas Whittaker, Toys Were Us: a History of Twentieth-Century Toys and Toy-Making (London: Orion, 2001), pp. 16–18. 103. Filz-Spielwaren-Fabrik, Katalog Stuttgart: Stähle & Friedel (1892) <http://www.teddybaer-antik.de/ baerenbis01.html> [accessed 11 February 2016]. 104. Edward VII: <http://www.royal. gov.uk/historyofthemonarchy/ kingsandqueensoftheunited kingdom/saxe-coburg-gotha/ edwardvii.aspx> [accessed 20 February 2016]. 105. Fawdry and Fawdry, Pollock’s History of English Dolls and Toys. 106. Pat Padua, The Library of Congress presents the Songs of America: ‘The Teddy Bear’s Picnic’ (2014) <http:// blogs.loc.gov/music/2014/02/ the-library-of-congress-presentsthe-songs-of-america-the-teddybears-picnic/> [accessed 12 March 2015]. 107. David Veart, Hello Girls and Boys: a New Zealand Toy Story (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2014), p. 161. 108. Murray, Translucent Building Skins, p. 55. 109. Pürckhauer, personal communication. 110. Sigfried Geidion, Space, Time and Architecture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), pp. 450–76. 111. David Yeomans and David Cottam, The Engineer’s Contribution to Contemporary Architecture (London: Thomas Telford Publishing, 2001). 112. Jaeggi, Fagus, p. 39. 113. Weidner, ‘Der Glaspalast 1903’. 114. Jürgen Ceislik and Marianne Cieslik, Knopf im Ohr (Jülich: Cieslik Verlag, 1989). 115. Royal Academy, 50 Years Bauhaus (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1968). 116. Throw Dolls: <http://bauhausonline.de/en/atlas/werke/throwdolls> [accessed 20 June 2015]. 117. Little Peg Dolls: <http://bauhausonline.de/en/atlas/werke/littlepeg-dolls> [accessed 20 June 2015]. 118. Jaeggi, Fagus, p. 58. 119. Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, pp. 32–3. Illustration credits arq gratefully acknowledges: Robert Vale, all images Acknowledgements We would like to offer special thanks to Simone Pürckhauer and her colleague Carmen Grall for kindly showing us round the 1903 Steiff building. Authors’ biographies Robert and Brenda Vale are architects and academics. They wrote their first book on sustainable design, The Autonomous House, in 1975 followed by Green Architecture in 1991. Their more recent books consider the environmental impact of lifestyles while their latest, Architecture on the Carpet (2013) explores the links over the last hundred years between architecture and construction toys such as Meccano, Bayko, and Lego. Authors’ addresses Brenda Vale brenda.vale@vuw.ac.nz Robert Vale robert.vale@vuw.ac.nz Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.