THE LIFE AND WORKS

OF IOSE RIZAL

5m.t30

ffittannnv

,0!r

jffit$ffiffiiiff'ffii1il-"'

I

Rt2l

s.a

#tla

]

TAnIE oF CoNTENTS

l

Quezon City

right @ 201.8 by C 6c E Publiehing, Inc.,

Rhodalyn Wa.ni-Obias, Aaron Abel Mallari,

and janel Reguindlr,hEstella

Preface

Chapter 1: Understanding the Rizal Law

Chapter 2: Nation and Nationalism

Chapter 3: RememberingRizal

Chapter

4z TheLifeofJos6Rizal

Chapter

5: The Nineteenth

.......

.

vii

1,

...

.1,3

...25

.....40

Century Philippine Economg

Mestizos . . . . 59

AgrarianDisputes.

. . .72

EmergingNationalism

. , . . .87

ImaginingaNation

...98

Society, and the Chinese

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication

may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cataloguing-in-Publication

DS

675

.8R62

.w36

20L8

Data

Wani-Obias, Rhodalyn

The li{e and works of Jos6 Rizal/Rhodalyn

Wani-Obias, Aaron A. Mallari, and Janet R. Estella.Quezon City: C & E Publishing, Inc,, @2018.

Chapter

Chapier

Chapter

8:

Chapter

9:

Noli Me Tdngere, Context and Content

Chapter 10: Noli Me Tdngere, Continuing Relevance.

108

Chapter 11: Looking at the Filipino Past

L27

Chapter 12: Indolence or Industry

135

119

Chapter

El Filibusterismo: Context and Content

Includes bibliography and index.

Chapter

El Filibusterismo: Continuing Relevance

1,52

ISBN: 978-971 -98-0936-4

Chapter

The Destiny of the Filipino People.

1,62

1.

Chapter

Biography and National History

L67

viii,

1.81 p. :

ill.;

cm.

Rizal,Jos6, 1861,-1.896. I. Mallari,Aaron A.

II. Estella, Janet

R.

III. Title.

Index

Book Design: PaullAndrew L. Pagunsan

Cover Design: Migudl Eriricb B. Dimagiba

tlo*tta

A- r

About the Authors

.

L42

1,75

Pnr,racE

In the nineteenth century, Filipino propagandists in Spain

bemoaned the state of education in the Philippines. They cited

as a barrier to educational progress "the old methods which

F

*i

L

=

e

they use to give strength to intellectual development... the

rudimentary system which seems glued to the abominable

magister dixit... the shallowness of the courses offered which

are completely parallel to the knowledge of the professor...

[which] are not frankly the best means of making the Filipinos

outstanding in their respective careers."l So problematic were

these points that it became difficult and inconvenient for Filipino

students to catch up and adjust when they pursued their studies

in Spain. Hence, the propagandists would also call for reforms in

Philippine education.

More than a century later, we are again faced with similar

sentiments. In a globalized world where technology has given us

modern-day conveniences and communication has broken down

age-old barriers, we confront the task of transforming how and

what one should learn in the twenty-first century.'SThere lecturebased classes formed the foundation of learning in past centuries,

the corpus of recent literature has argued for a more studentcentered pedagogy. Underlying this argument is the assumption

that different times entail different demands from our learnersl

1

Guadalupe Fores-Ganzon, trans., "The University of Manila: lts Curriculum:' in Lo Solidoridod,

15 December 1890 (Philippines: Fundacion Santiago, 1996): 583.

vtt

hence,

the skills that were once useful in the past may not

necessarily be applicable today.

It is in relation to these changes that the Commission of

Higher Education (CHED) released a memorandum in 2013

emphasizing a "paradigm shift to learning competency-based

standards in Philippine higher education."2 Eight core courses

were institutionalized along with the already-mandated course of

CHAPTER I

UNDERSTANDING

THE RIZAL LAW

Rizal's life and works.

This particular book on Rizal's life and works is a direct

product of these efforts to bring Philippine education closer to

what is needed and expected in the twenty-first century.'!7hile

the course on Rizal has been mandated by law since 1956, newer

approaches to studying Rizal's life and works were used in this

book. It is our hope that as we continuously adapt to changes in

our education, our understanding of Rizal continue to evolve as

well, making an appreciation of our hero's life and works fitting

to Filipinos of various generations.

he mandatory teaching of Jos6 Rizal's life with the emphasis

on his landmark novels is inscribed in legislation. Republic Act

No. 1425, more popularly known as the Rizal Law, was passed in

1956 leaving a colorful narrative of debate and contestation.

As an introduction to the life and works of Jos6 Rizal, this textbook

will begin with the reading of the Rizal Law. ln this chapter, you will

study RA 1425 within its context, look into the major issues and debates

surrounding the bill and its passage into law, and reflect on the impact

and relevance of this legislation across history and the present time.

ln the course of the discussion, the process of how a bill

becomes a law in the Philippines will be tackled so you will have an

idea regarding the country's legislative process. The life of one of the

major champions of the Rizal Law, Senator Claro M. Recto, will also be

discussed.

At the end of this chapter, the students should be able to:

y'

/

locale the passage of the Rizal Lawwithin its historical contex|

determine the issues and interests at stake in the debate over the

Rizal Bill;and

2

'z

Commission on Higher Education, "General Education Curriculum: Holistic Understandings,

lntellectual and Civic Competencies." Accessed on 13 July 2017 from http://www.ched.govphi

wp-contenVuploa dsl 2013l07 /CMO-No.2O-s2013.pdf.

utlt

relate the issues to the present-day Philippines.

2

T:':,r. l.rFE AND woRKS

bill

-

oF JosE RizAL

UNDERSTANDINC THE RIZAL LAw

a measure which, if passed through the legislative process,

STEP

becomes a law

unexpurgated

6

-

basically untouched. ln the case of the novels of Rizal,

unexpurgated versions were those that were not changed or censored

to remove pafts that might offend people.

Voting on Third Reading. Copies of the final

versions of the bill are distributed to the

members of the Senate who will vote for its,

approval or rejection.

Consolidation of

Version from the

bicameral - involving the two chambers of Congress: the Senate and

the House of Representatives

Voting on Second

Reading. The senators

-

The Context of the Rizal Bi!!

STEP 5

vote on whether to

approve or reject the

bill. lf approved, the bill

STEP 7

is calendared for third

The postwar period saw a Philippines rife with challenges

and problems. With a country torn and tired from the stresses of

World'V7ar II, getting up on their feet was a paramount concern

of the people and the government.

3

House. The similar

steps above are

followed by the House

of Representatives in

coming up with the

approved bill. lf there

are differences between

the Senate and House

versions, a bicameral

conference committee

is called to reconcile

reading.

I

the two. After this, both

chambers approve the

consolidated version.

STEP 8

Bill is filed in the Senate Office

of the Secretary. lt is given a

number and calendared for first

reading.

I

STEP

I

Second Reading.

The bill is read and

discussed on the floor.

The author delivers a

sponsorship speech.

The other members

of the Senate may

engage in discussions

regarding the bill

and a period of

debates will pursue.

Amendments may be

suggested to the bill.

Transmittal of the Final Version to

Malacafian. The bill is then submitted

to the President for signing. The

President can either sign the bill into

law or veto and return it to Congress.

First Reading.

The bill's title,

number, and

autho(s) are

read on the floor.

Afterwards, it

is referred to

the appropriate

committee.

STEP 2

Committee Hearings. The bill is discussed within the committee

and a period of consultations is held. The committee can

approve (approve without revisions, approve with amendments,

or recommend substitution or consolidation with similar bills) or

reject. After the committee submits the committee report, the bill

is calendared for second reading.

4

Irtti LrrE AND WoRKS OF IOSE RrZAL

As the

Philippines grappled

with various

UNDERSI'ANDING THE RlZAL LAw

challenges,

particularly the call for nation-building, prominent individuals who

championed nationalism came to action. They pursued government

measures to instill patriotism and love for country in the hearts

and minds of the Filipinos. These people drew inspiration from the

Philippine experience of the revolution for independence against

Spain and from the heroes of that important period in the country's

history.

One measure sought was the passage of the Republic Act

No. 1425 or the Rizal Law, which was primarily set to address

"a need for a re-dedication to the ideals of freedom and

nationalism for which our heroes lived and died." The passage of

the law was met with fierce opposition in both the Senate and the

House of Representatives.

From the Rizal Bill to the Rizal Law

On April 3, 1.956, Senate Bill No. 438 was filed by the

Senate Committee on Education. On Apil17,1956,then Senate

Committee on Education Chair Jose P. Laurel sponsored the

bill and began delivering speeches for the proposed legislation.

Soon after, the bill became controversial as the powerful Catholic

Church began to express opposition against its passage. As the

influence of the Church was felt with members of the Senate

voicing their opposition to the bill, its main author, Claro M.

Recto, and his allies in the Senate entered into a fierce battle

arguing for the passage of SB 438. Debates started on April 23,

1956.

The debates on the Rizal Bill also ensued in the House

oi R.pr.r.ntatives. House Bill No. 5561,, an identical version

of SB 438, was filed by Representative Jacobo Z. Gonzales

on April 19, 1956. The House Committee on Education

approved the bill without amendments on May 2,1956 and

the debates commenced on May 9,1956. A major point of

the debates was whether the compulsory reading of the texts

CLARO M. RECTO

(February,8, 1890-October 2,

19601

:,

,.

,:,

::.: :

The main sponsor and defender of the Rizal

,

Bill

was Claro Mayo Recto. He was born in Tiaong, Tayabas

(Quezon) on February 8, 1890 to Claro Recto, Sr. and

Micaela Mayo. He completed his primary education in his

hometown and his,;s€condallr education in Batangas. For

his college education, he moved to Manila and completed

his AB degree at the Ateneo and was awarded moximo

cum loude in 1909. ln 1914, he finished his law degree from

the Univefsity of Santo Tomas,. He was admitted to the bar

that same year.

;

1':

lli!

';

o

in the House of

he was elected as

:pralitical,, aareer 1111516ll"O

Leader, and Senate President Pro-Tempore. Recto's career

in the Philippine government was not confined to the

legislature. ln 1935, he became Associate Justice of the

Supreme Court.

Reclo Waq. also instrumental in the drafting of the

constitution of the Philippines in 1934-'!935 as he was

seleiteO prasiOent of tne assembly. After the Phitipplnes

transitioned, to,the Cdmmonwealth Period and surviVed

the Pacific War, Recto again served as senator for several

terms. He also served as diplomat and was an important

figure in interyational relations.

fnown

'as,

o

o

o

c

f,

RepresentatiVes'',''in:,,,1919':when

representative of the third district of Batangas. He later

became House Minority Floor Leader. From the House of

Repiesentatives; he moved to the Senate,in 1931 when

he was elected as a senator. ln the Senate, he held key

positions such as Minorlty Floor Leader, Majority Floor

I

!

J

lan ardent nationalis!, Recto was also

a

man of letters. He penned beautiful poetry and prose. On

October 2, 1960, he died of a heart attack in ltaly. He was

survived by his wife, Aurora Reyes and their flve children.

o

f

o

zo

d

o

f

9r

q

=.

o

a

o

=

o

-o

f,

p=

!.l

o

5

6 trrI

LrFE AND WORKS oF

losE RrzAL

UNDERSTANDINC THE RIZAL LAW

Noli Me Tdngere and El Filibusterismo appropriated in the

bill was constitutional. The call to read the unexpurgated

versions was also challenged.

As the country was soon engaged in the debate, it seemed

that an impasse was reached. To move the procedure to the next

step, Senator Jose P. Laurel proposed amendments to the bill on

May 9,1956.In particular, he removed the compulsory reading

of Rizal's novels and added that Rizal's other works must also

be included in the subject. He, however, remained adamant in his

stand that the unexpurgated versions of the novels be read. On

May 14,1956, similar amendments were adopted to the House

version.

The amended version of the bills was also subjected to

scrutiny but seemed more palatable to the members of Congress.

i

The passage, however, was almost hijacked by technicality since

the House of Representatives was about to adjourn in a few

days and President Ramon Magsaysay did not certify the bills as

priority. The allies in the House skillfully avoided the insertion of

any other amendment to prevent the need to reprint new copies

(which would take time). They also asked the Bureau of Printing

to use the same templates for the Senate version in printing the

House version. Thus, on May 17,1956, the Senate and House

versions were approved.

The approved versions were then transmitted to Malacaflan

and on Jtrne 12,1956, President Magsaysay signed the bill into

law which became Republic Act No. 1425.

The Debates about the Rizal Bill

Read the following excerprs from the statements of the

It'gislators who supported and opposed the passage of the Rizal

l.;rw in 1956. Then, answer the questions that follow.

FOR

"Noli Me Tdngere and E/ Filibusterismo must be read by all Filipinos.

They must be taken to heart, for in their pages we see ourselves as

in a mirror, our defects as well as our strength, our virtues as well as

our vices. Only then would we become conscious as a people and

so learn to prepare ourselves for painful sacriflces that ultimately

lead to self-reliance, self-respect, and freedom."

-Senator Jose

P.

Laurel

"Rizal did not pretend to teach religion when he wrote those

books. He aimed at inculcating civic consciousness in the Filipinos,

national dignity, personal pride, and patriotism and if references

were made by him in the course of his narration to certain religious

practices in the Philippines in those days, and to the conduct

and behavior of erring ministers of the church, it was because he

portrayed faithfully the general situation in the Philippines as it then

existed."

-Senator Claro M. Recto

ASAII\ST

'A vast majority of our people are, at the same time, Catholic and

Filipino citizens. As such, they have two great loves: their country

and their faith. These two loves are not conflicting loves. They are

harmonious affections, like the love'for his father and for his mother.

This is the basis of my stand. Let us not create a conflict between

nationalism and religion, between the government and the church."

-Senator Francisco "Soc" Rodrigo

g

8

t

UNDERSTANDu'lc rHE RIZAL LAW

uE LrFE AND woRKS oF Josd RrzAL

9'...

Questions

1.

2.

'S7hat

was the major argument raised by Senator Francisco

"Soc" Rodrigo against the passage of the Rizal Bill?

The Rizal Law and the Present Context

In groups, talk about the preceding questions and prepare a

sf-rort summary of your discussion points to be presented in class.

The Rizal Law

'!7hat

was the major argument raised by Senators Jose

P. Laurel and Claro M. Recto in support of the passage of

the Rizal Bill?

REPUBLIC ACT NO. 1425

AN ACT TO INCLUDE IN THE CURRICULA OF ALL PUBLIC AND

PRIVATE SCHOOLS, COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES COURSES ON

THE LIFE, WORKS AND WRITINGS OF JOSE RIZAL, PARTICULARLY

HIS NOVELS NOLI ME TANGERE AND EL FILIBUSTERISMO,

AUTHORIZING THE PRINTING AND DISTRIBUTION THEREOF, AND

FOR OTHER PURPOSES

WHEREAS, today, more than any other period of our history there

is a need for a re-dedication to the ideals of freedom and nationalism for

which our heroes lived and died;

Are there points of convergence between the supporters and

opposers of the Rizal Bill based on these statements?

WHEREAS, it is meet that in honoring them, particularly the national

hero and patriot, Jose Rizal, we remember with special fondness and

devotion their lives and works that have shaped the national character;

WHEREAS, the life, works and writing of Jose Rizal, particularly his

novels No/i Me Tongere and El Filibusterismo, are a constant and inspiring

source of patriotism with which the minds of the youth, especially during

their formative and decisive years in school, should be suffused;

WHEREAS, all educational institutions are under the supervision of,

and subject to regulation by the State, and all schools are enjoined to

develop moral character, personal discipline, civic conscience and to

teach the duties of citizenship; Now, therefore,

l0

l'HE LrFE AND WoRKS oF JosE RrzAL

U

NDERSTANDINC THE RIZAL.+w

l1

ta

SECTION 1. Courses on the life, works and writings of Jose Rizal,

particularly his novels Noli Me Tongere and E/ Filibusterismo, shall be

included in the curricula of all schools, colleges and universities, public

or private: Provided, That in the collegiate courses, the original or

unexpurgated editions of the No/l Me Tongere and E/ Filibusterismo or

their English translation shall be used as basic texts.

The Board of National Education is hereby authorized and directed

to adopt forthwith measures to implement and carry out the provisions

of this Section, including the writing and printing of appropriate primers,

readers and textbooks. The Board shall, within sixty (60) days from the

effectivity of this Act, promulgate rules and regulations, including those

of a disciplinary nature, to carry out and enforce the provisions of this

Act. The Board shall promulgate rules and regulations providing for the

exemption of students for reasons of religious belief stated in a sworn

written statement, from the requirement of the provision contained in

the second part of the first paragraph of this section; but not from taking

the course provided for in the first part of said paragraph. Said rules and

regulations shall take effect thirty (3O) days after their publication in the

Officiol Gozette.

SECTION 2. lt shall be obligatory on all schools, colleges and

universities to keep in their libraries an adequate number of copies

of the original and unexpurgated editions of the No/i Me Tongere and

El Filibusterisrno, as well as of Rizal's other works and biography. The

said unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tongere and Et Filibusterismo

or their translations in English as well as other writings of Rizal shall be

included in the list of approved books for requlred reading in all public

or private schools, colleges and universities.

The Board of National Education shall determine the adequacy of

the number of books, depending upon the enrollment of the school,

SECTION 4. Nothing in this Act shall be construed as amendment

or rc.pealing section nine hundred twenty-seven of the Administrative

t.ode, prohibiting the discussion of religious doctrines by public school

Ir.rrchers and other persons engaged in any public school.

SECTION 5. The sum of three hundred thousand pesos is hereby

,

rrrthorized to be appropriated out of anyfund not otherwise appropriated

irr

the National Treasury to carry out the purposes of this Act.

SECTION 6. This Act shall take effect upon its approval.

Approved: June 12, 1956

Published in the OlifrclolGozette, Vol. 52, No. 6, p. 2971in June'1956.

The Rizal Law could be considered a landmark legislation

rn the postwar Philippines. During this period, the Philippines

was trying to get up on its feet from a devastating war and

rrirning towards nation-building. As the government sought

ways to unite the people, legislators like Claro M. Recto drew

inspiration from the lives of the heroes of the revolution against

Spain. In this frame, the teaching of the life and works of Jos6

Ilizal, particularly the reading of his novels No/i Me Tdngere and

lil Filibusterismo, was proposed to be mandated to all private

and public educational institutions. The proposed legislation,

however, met opposition particularly from the Catholic Church.

After much debate, the proposed bill was eventually signed into

law and became Republic Act No. 1425.

college or university.

SECTION 3. The Board of National Education shall cause the

translation of the No/i Me Tongere and El Filibusterismo, as well as other

writings of Jose Rizal into English, Tagalog and the principal philippine

dialects, cause them to be printed in cheap, popular editions; and cause

them to be distributed, free of charge, to persons desiring to read them,

through the Purok organizations and Barrio Councils throughout the

country.

Constantino, Renato. 1969. The Rizal Law and the Catholic

hierarchy. kt The making of a Filipino: A story of Philippine

colonial politics, pp.244-247. Quezon City: Malaya Books.

Laurel,.|ose B., .lr. 1,960. The trials of the Rizal Bill. Historical

B wll etin 4 (2) : 1, 3 0-1. 3 9 .

l2

'rHE LlFE AND woRKs oF

losd RrzAL

Republic of the Philippines.1,956. Republic Act 1425.Available

from http ://www. of ficial gazette. gov.phl 1 9 5 6 I 0 6 I 12 h epublicact-no-L4251

CHAPTER 2

Schumacher, John. 20LL. The Rizal Bill of 1.956: Horacio de la

Costa and the bishops. Philippine Studies 59(4): 529-553.

NeUoNAND

Website of the Senate of the Philippines. "Legislative Process."

Available from https://www.senare.gov.ph/about/legpro.asp

NeUoNALISM

he previous chapter stated that one of the major reasons

behind the passage of the Rizal Law was the strong intent to

instill nationalism in the hearts and minds of the Filipino youth.

This chapter will now focus on nation and nationalism in the Philippine

context. lt will explain the concepts of nation, state, and nation-state as

a precursor to understanding nationalism and the projects that lead to

it. Likewise, the discussion will touch on some of Rizal's works that deal

with nation and nationalism.

The chapter also aims to reflect on nation-building in the Philippines

which is a major force behind the passage of the Rizal Law.

At the end of this chapter, the students should be able to:

P

deflne nationalism in relation tq the concepts of nation, state, and

nation-state;

,b

r'

appraise the development of nationalism in the country; and

explain the relevance of nationalism and nation-building at present.

l4 Irn, 1-rrrE AND WORKS or iosE RIZAL

NATToN AND NATToNALtsM

boyon/bonuo - indigenous Filipino concepts of community and

territory that may be related to nationalism

nation

-

a group of people with a shared language, culture, and history

nation-building - a project undertaken with the goal of strengthening

the bond of the nation

nation-state

-

patriotism

a feeling of attachment to one's homeland

-

a state ruling over a nation

- the authority to govern a polity without external

interference/incursions

sovereignty

Nation, State, Nation-State

To better understand nationalism, one must learn first the

concepts of nation and nationhood as well as state and nationstate. Refer to the following summary:

Social scientists have fleshed out the nuances of nation,

statc, and nation-state. A nation is a community of people that

are bclicved to share a link with one another based on cultural

practices, languagc, religion

or belief

system, and historical

15

\

to name a few. A state, on the other hand, is a

l,olitical entity that has sovereignty over a defined territory.

,'rpt:rience,

\r:ttcs have laws, taxation, government, and bureaucracyl,rrsically, the means of regulating life within the territory.

llris sovereignty needs diplomatic recognition to be legitimate

.rrrrl acknowledged internationally. The state's boundaries and

tt r-ritory are not fixed and change across time with war, sale,

,rr'[ritration and negotiation, and even assimilation or secession.

The nation-state, in a way, is a fusion of the elements of

tlrc nation (people/community) and the state (territory). The

,lt'velopment of nation-states started in Europe during the

pcriods coinciding with the Enlightenment. The "classical"

rr:rtion-states of Europe began with the Peace of 'Westphalia in

tlrc seventeenth century. Many paths were taken towards the

Iormation of the nation-states. In the "classical" nation-states,

rurrny scholars posit that the process was an evolution from

lrcing a state into a nation-state in which the members of the

lrureaucracy (lawyers, politicians, diplomats, etc.) eventually

rrroved to unify the people within the state to build the nationstrrte. A second path was taken by subsequent nation-states

which were formed from nations. In this process, intellectuals

rrrrd scholars laid the foundations of a nation and worked

towards the formation of political and eventually diplomatic

lccognition to create a nation-state. A third path taken by many

Asian and African people involved breaking off from a colonial

rclationship, especially after 'World 'War II when a series of

rlccolonization and nation-(re)building occurred. During this

time, groups initially controlled by imperial powers started to

irssert their identity to form a nation and build their own state

from the fragments of the broken colonial ties. A fourth path

was by way of (sometimes violent) secessions by people aheady

part of an existing state. Here, a group of people who refused

to or could not identify with the rest of the population built a

nation, asserted their own identity, and demanded recognition. In

tl-re contemporary world, the existing nation-states continuously

l6

NATToN AND NA'rroNAlls,r,t 17

tlrL. t.rFE AND woRKS oF Josi RIZAL

strive with proiects of nation-building especially

since

globalization and transnational connections are progressing.

Nation and Nationalism

As mentioned, one major component of the nation-state

is the nation. This concept assumes that there is a bond that

connects a group of people together to form a community. The

origin of the nation, and concomitantly nationalism, has been

a subject of debates among social scientists and scholars. In

this section, three theories about the roots of the nation will be

presented.

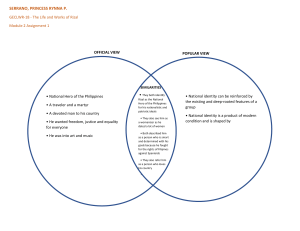

The first theory traces the root of the nation and national

identity to existing and deep-rooted features of a group of

people like race, language, religion, and others. Often called

primordialism, it argues that a national identity has always

existed and nations have "ethnic cores." In this essentialist stance,

one may be led to conclude that divisions of "us" and "them"

are naturally formed based on the assumption that there exists

an unchanging core in everyone. The second theory states that

nation, national identity, and nationalism are products of the

modern condition and are shaped by modernity. This line of

thinking suggests thdt nationalism and national identity are

necessary products of the social structure and culture brought

about by the emergence of capitalism, industrialization,

secularization, urbanization, and bureaucratization. This idea

further posits that in pre-modern societies, the rigid social

hierarchies could accommodate diversity in language and

culture, in contrast with the present times in which rapid change

pushes statehood to guard the homogeneity in society through

nationalism. Thus, in the modernist explanation, nationalism is a

political project.

The third theory-a very influential explanationabout nation and nationalism maintains that these ideas are

discursive. Often referred to as the constructivist approach

lo

l

understanding nationalism,

this view maintains

that

rr:rtionalism is socially constructed and imagined by Beople who

itlcntify with a group. Benedict Anderson argues.that nations

,rrc "imagined communities" (2003). He tr,acds the history

,,f these imagined communities to the Enlightenment when

lruropean society began challenging the supposed divinely,rrdained dynastic regimes of the monarchies. This idea was

starkly exemplified by the Industrial Revolution and the French

Itcvolution. The nation is seen as imagined because the people

who affiliate with that community have a mental imprint of

the affinity which maintains solidarity; they do not necessarily

rrced to see and know all the members of the group.\JTith this

inragined community comes a "deep, horizontal comradeship"

tlrat maintains harmonious co-existence and even fuels the

willingness of the people to fight and die for that nation.

Anderson also puts forward the important role of mass media in

the construction of the nation during that time. He underscores

that the media (1) fostered unified fields of communication

which allowed the millions of people within a territory to

"know" each other through printed outputs and become

rrware that many others identified with the same community;

(2) standardized languages that enhanced feelings of nationalism

end community; and (3) maintained communication through a

few languages widely used in the printing press which endured

through time.

Nation and Boyon

In the Philippines, many argue that the project of nationbuilding is a continuing struggle up to the present. Considering

the country's history historians posit that the nineteenth century

brought a tremendous change

in the lives of the Filipinos,

including the actual articulations of nation and nationhood that

culminated in the first anti-colonial revolution in Asia led by

Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan. Furthermore, scholars note

l8

NATIoN AND NATToNALTsM 19

'[HE LrFE AND WoRKS oF Josti F.rzAL

the important work of the propagandists like Rizal in the

sustained efforts to build the nation and enact change in the

Spanish colony. These themes will be discussed in the succeeding

chapters. As you continue to familiarize yourselves with the

concepts of nation and nationalism, it would be worthwhile to

look at how these ideas have been articulated in the past as well

as how scholars locate these efforts in the indigenous culture.

Many Filipino scholars who endeavored to

understand

have

identified

concepts

that relate

knowledge

indigenous/local

to how Filipinos understand the notions of community and, to

an extent, nation and nation-building. The works of Virgilio

Enriquez, Prospero Covar, and Zeus Salazar, among others,

attempted to identify and differentiate local categories for

communities and social relations. The indigenous intellectual

movements like Sikolohiyang Pilipino and Bagong Kasaysayan

introduced the concepts of kapua and bayan that can enrich

discussions about nationalism in the context of the Philippines.

Kaputa is an important concept in the country's social

relations. Filipino interaction is mediated by understanding

one's affinity with another as described by the phrases "ibang

tAo" and "'di ibang tao." In the formation and strengthening

of social relations, rhe kapwa concept supports the notion of

unity and harmony in a community. From this central concept

arise other notions such as "pakikipagkdpwA," "pdkikisama,"

and "pakikipag-ugnay," as well as the collective orientation of

Filipino culture and psyche.

In the field of history, a major movement in the

indigenization campaign is led by Bagong Kasaysayan, founded

by Zeus Salazar, which advances the perspective known as

Pantayong Pananaw. Scholars in this movement are among the

major researchers that nuance the notion of bayan or banua.

In understanding Filipino concepts of community, the bayan

is an important indigenous concept. Bayan/Banua, which can

be traced all the way to the Austronesian language family, is

loosely defined as the territory where the people live or the

community they are identifying with. Thus, bayan/banua

( n( orrrpasses both the spatial community 4s well as the imagined

,,,rrrrnunity. The concept of bayan claslied with the European

r< rt ion of naci6n during the Spanish colonialism. T'he proponents

r rl I)antayong Pananaw maintain the existence of a great cultural

,lrvide that separated the elite (naci6n) and the folk/masses

lltlyan) as a product of the colonial experience. This issue brings

tlrc project of nation-building to a contested terrain.

,rt rurrl

r

Throughout Philippine history, the challenge of building the

I ilipino nation has persisted, impacted by colonialism, violent

rrrvasion during ITorld'$Var II, a dictatorship, and the perennial

\truggle for development. The succeeding chapters will look into

rlre life and works of Jos6 Rizal and through them, try to map

lrow historical events shaped the national hero's understanding of

the nation and nationalism.

Concept Map

Make a concept map summarizing:

o

o

the major points in relation to nation and nationalism;

the definitions of nation and nationalism, and their

relationship to state and nation-state; and

o

the development and explanatory models of the origins

of state and nation-state.

20

\\

.I'IIE LIFE AND WORKS OF

JOSf R]ZAL

NAT]ON AND NAT]..ONALISM

\

Exchange concept maps with a classmate. Have him/her rate

your work using the following rubric:

Excerpts from Emilio Jacinto's Kartilya ng

Liwanag at Dilim

Katipuiqn and

.ri i...ri.rr_,r:.r:;rrr:::r:r':i:itrrri:...,.

.i.i..ri:.lt'rr.i'rtr.:l

Sfiidtnt

,l..Elc€llgrittli:,rlrutt

gC.6..Ig.r',!l::i.:

:,1::lrr,l:l:::,t*:::::t, l].:l:,:;l:l::r,ll

6r.

t!

Nrl

Gl.:

Eil

o,:

Well organized

Thoughtfully

organized

Somewhat

organized

Choppy

Logical format

Contains main

concepts

Easy to follow

Somewhat

confusing

most of the

incoherent

time

Contains

only a few

of the main

concepts

Contains

a limited

number of

concepts

Contains a

appropriate

number of

concepts

Contains

most of

the main

Map is "treelike" and not

stringy

Follows

standard map

conventions

Linking words

demonstrate

E:

:.1t:

t

()

:o

.'..:i

concepts

Contains an

adequate

number of

concepts

Follows the

standard map

conventions

conceptual

understanding

Linking words

are easy to

follow but at

times ideas

are unclear

Links are

precisely

labeled

Links are

not precisely

labeled

superior

and

Linking

words are

clear but

present

a flaweci

rationale

Difflcuit

to follow

No links

Links are

not labeled

Adapted from: National Computational Science Education Consortium. (n.d.). Rubrrcs for concept mop.

Available from www.ncsec.org/team11/RubricconceptMap.doc

Kartilya ng Kdtipunan:

May Nasang Makisanib Sa Katipunang lto

Sa

Sa pagkakailangan,

ta

ar.g lahat na nagiibig pumasuk

ito, ay magkaroon ng lubos na pananalig

at kaisipan sa mga layong tinutungo at mga kaaralang

pinaiiral, minarapat na ipakilala sa kanila ang mga bagay

na ito, at ng bukas makalawa'y huag silang magsisi

at tuparing maluag sa kalooban ang kanilang mga

tungkulin.

sa katipunang

Ang kabagayang pinag-uusig ng katipunang ito ay lubos

na dakila at mahalaga; papagisahin ang loob at kaisipan

ng lahat ng tagalog (") sa pamagitan ng isang mahigpit

na panunumpa, upang sa pagkakaisang ito'y magkalakas

na iwasan ang masinsing tabing na nakabubulag sa

kaisipan at matuklasan ang tunay na landas ng Katuiran

at Kaliwanagan.

(")

salitangtagalog katutura'y ang lahat nang tumubo

sa Sangkapuluang ito; sa makatuid, bisaya man, iloko

man, kapangpangdn man, etc., ay tagalog din.

Sa

Dito'y isa sa mga kaunaunahang utos, ang tunay na pagibig sa bayang tinubuan at lubos na pagdadamayan ng

isa't isa.

Articulations of Nation and Nationalism

Enrich your understanding by looking at how nationalism is

espoused by other historical figures. Read the excerpts from the

writings of another important thinker in the nineteenth century,

Emilio Jacinto, and answer the questions that follow.

2t

Liwanag at Dilim

"Arrg alinmang katipunan at pagkakaisa ay

ng isang pinakaulo, ng isang

kapangyarihang makapagbibigay ng ayos,

nangangailangan

makapagpapanatili ng tunay na pagkakaisa at makapagaakay sa hangganang ninanais, katulad ng sasakyang

22

THE LrFE AND woRKS oF

o*

Josf RIzAL

itinutugpa ng bihasang piloto, Ra kung ito'y mawala ay

nanganganib na maligdw at abutin ng kakila-kilabot

na kamatayan sa laot ng dagat, na di na makaaasang

makaduduong sa pampang ng maligaya at payapang

kabuhayang hinahanap. Attg pinakaulong ito ay

tinatawag na pamahalaan.

b.

AND NATIoNALISM 23

Leadership

"Ang kadahilanan nga ng mga pinuno ay angbayan, at

ang kagalingan at kaginhawahan nito ay siyang tanging

dapat tunguhin ng lahat nilang gawa at kautusan.

Tungkol nila ang umakay sa bayan sa ikagiginhawa,

kailan pa ma\maghirap at maligaw ay kasalanan nila.

"[A]ng alinmang kapangyarihan upang maging tunay

at matuwid ay sa Bayan lamang at sa kanyang mga

tunay na pinakakatawan dapat na manggaling. Sa

madaling salita, di dapat nating kilalanin ang pagkatao

How does the Katipunan understand/make

sense

of

the

trlrprno natloni

ng mga pinuno na mataas kaysa madla. Ang pagsunod

at pagkilala sa kanila ay dahil sa kapangyarihang

ipinagkaloob ng bayan, samakatu#id, ang kabuuan

ng kapangyarihan ng bawat isa. Sa bagay fla ito,

ang sumusunod sa pinunong inilagay ng bayan ay

dito sumusunod at sa paraang ito'y nakikipagisa sa

kalahatan."

Questions

1. How

does the Katipunan understand/make sense

following?

a.. State and Government

of the

\X/hat are your reflections on these writings about some

important ideas of the Katipunan?

GT

r'

.,

t

24

THE t-rFE AND woRKs oF JosE RIZAL

As stated in the first chapter, the imperative of instilling

nationalism in the minds of the youth was a major factor

behind the passage of the Rizal Law. To have a basic grasp of

nationalism, the concepts of nation, state, and nation-state

must be examined. This chapter explained the basic definitions

of nation (a community of people), state (a political entity),

and nation-state (a fusion of the previous two) and traced the

development of the nation-state. It then tackled the various ways

by which social scientists made sense of the concepts of nation

and nationalism, their origins, and development. Discussed

were the primordialist, modernist, and social constructionist

approaches as lenses in which nationalism could be viewed'

The chapter ended with a brief discussion about nationalism

in the context of the Philippines, particularly how indigenous

knowledge could be used to examine how Filipinos understand

REMEMBERING

RIZAL

izal's execution on December 30, 1896 became an important

turning point in the history of Philippine revolution. His death

the concepts of nation and nationalism.

As you study the life of Jos6 Rizal,

it is important to remind

yourself of the multiplicity of ideas during his time and beyond

that will affect your understandings of nation and nationalism.

Abinales, Patricio and Donna Amoroso. 2005. State and society

in th e P h ilipp ines. P asig: Anvil Publishing, Inc.

Anderson, Benedict. 2003. lmagined communities: Reflections

on the origins and spread of nationalism. Pasig: Anvil

Publishing,Inc.

Aquino, Clemen. Mula sa Kinaroroonan: Kapwa, kapatiran, at

bayan sa agham panlipunan. CSSP Centennial Professorial

Chair PaPers Series of 1999.

Gallaher, Caroline, et al. 2009. Key concepts in political

geography. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Griffiths, Martin, et al. 2002. lnternational relations: The key

concepts. London: Routledge.

activated the full-scale revolution that resulted in the declaration

,rl Philippine independence by 1898. Under the American colonial

,l,rvcrnment, Rizal was considered as one of the most important Filipino

lnroes of the revolution and was even declared as the National Hero

lry lhe Taft Commission, also called the Philippine Commission of

l')o1. A Rizal monument was built in every town and December 3O

w,r', declared as a national holiday to commemorate his death and

lr(,roism. ln some provinces, men-most of whom were professionals,

,urized and became members of Cobolleros de Rizol, now known as

'r(

llrr . (nigfi[5 of Rizal.

f

lnfluenced by both the Roman Catholic Church and the prehispanic

.lrirrltral culture, some Filipino masses likewise founded organizations

tlr.rl rccognize Rizal not just as an important hero but also as their

.,rvior from all the social ills that plague the country. These groups,

rrylrlr lr cafl be linked to the long history of millenarian movements in

llr'. ( ()untry, are widely known as the Rizalistas. These organizations

lrr'll1,v1' that Rizal has a Latin name of Jove Rex Al, which literally means

t ,, rr l, Kihg of All." This chapter will discuss the history and teachings of

, l,'r li.rl Rizalista groups founded after Rizal's execution.

RIMEM

lFll, l-lFE AND W0RKS ol' losE ll-lzAL

)6

n Er1

rN

c R rzAL

27

of Mount Makiling" (Ileto, 1998). Similar stories

,.nlirrued to spread after Rizal's death towards the end of the

nrrrt'tcenth century. The early decades of 1900s then witnessed

tlr, f<runding of different religious organizations honoring Rizal

rrr tlrc heart

At the end of this chapter, the students should be able to:

P

A

P

evaluate Rizal's heroism and importance in the context of Rizalista

groups;

discuss the history of selected Rizalista groups; and

compare and contrast the different views on Rizal among the

Rizalistas.

socio-political movements who generally believe

in the coming of a major social transformation with the establishment of

the Kingdom of God

Millenarian groups

Rizalista

-

-

a religious movement that believes in the divinity of Josti

Rizal

the Latin name of Jos6 Rizal according to Rizalistas; Jove

means God; Rex means King; and A/ means All (thus, God, King of All)

Jove

Rex

Al

-

colorum - a term used to refer to secret societies that fought against

the colonial government in the Philippines

canonization

-

the act of declaring a dead person as a saint

Rizal as the Tagalog Christ

In late 1898 and early

1'899, revolutionary newspapets La

lndependencia and El Heraldo de la Reuolucion reported about

Filipinos commemorating Rizal's death in various towns in the

country. In Batangas, for example, people were said to have

gathered "tearfully wailing before a portrait of Rizal" (Ileto,

1,998) while remembering how Christ went through the same

struggles. After Rizal's execution, peasants in Laguna were also

reported to have regarded him as "the lord of a kind of paradise

"Filipino Jesus Christ" (Ocampo, 2011).

In 1907, Spanish writer and philosopher Miguel de

llrrrruruno gave Rizal the title "Tagalog Christ" as religious

,rrsrrnizations venerating him had been formed in different

t).u-ts of the Philippines (Iya, 2012). It is, however, importanr

to rnention that Rizal was not the first to be called as such. In

lristory, Apolinario de la Cruz (1815-1841) who founded the

rt'ligious confraternity Cofradia de San /ose was also considered

:rs the "Tagalog Christ" by his followers. Moreover, Filipino

rt'volutionary Felipe Salvador (1870-1912), also known as

i\;ro Ipe, who founded the messianic society Santa lglesia (Holy

( )hurch) was called by his followers as the "Filipino Chrisr" and

tlre "King of the Philippines." The titles given to some earlier

Irilipino revolutionary leaders reveal that associating religious

hcliefs in the social movement is part of the country's history.

I'cachings and traditions of political movements that were

organized to fight the Spanish and American colonial powers

were rooted in religious beliefs and practices. These sociorcligious movements known as the millenarian groups which aim

to transform the society are often symbolized or represented by a

hero or prophet.

r., thc

The same can also be said with the Rizalista groups which, as

nrentioned, have risen in some parts of the country after Rizal's

clcath in 1896. Each group has its own teachings, practices,

and celebrations, but one common belief among them is the

veneration of Jos6 Rizal as the reincarnation of .|esus Christ.

'Ihese groups likened the travails of

Rizal to that

Jos6

of Jesus

Christ as narrated in the Pasyon, an epic poem which became

popular among the Tagalogs during the Spanish period (Ileto,

1998). Rizalistas believe that Rizal, just like Jesus Christ, would

eventually return to life and will save mankind.

28

THE LrFE AND woRKS oF ,osd RIZAL

People saw the parallel between the two lives being sent

into the world to fulfill a purpose. As Trillana (2006, p. 39) puts

it, "For both Jesus and Rizal, life on earth was a summon and

submission to a call. From the beginning, both knew or had

intimations of a mission they had to fulfill, the redemption of

mankind from sin in the case of Jesus and the redemption of his

people from oppression in the case of Rizal."

Reincarnation in the context of Rizalistas means that both

Rizal and Jesus led parallel lives. "Both were Asians, had brilliant

minds and extraordinary talents. Both believed in the Golden

Rule, cured the sick, were rabid reformers, believed in the

universal brotherhood of men, were closely associated with a

small group of followers. Both died young (Christ at 33 and

Rizal at 35) at the hands of their enemies. Their lives changed the

course of history" (Mercado, 1,982rp.38).

The Canonization of Rizal:

Tracing the Roots of Rizalistas

The earliest record about Rizal being declared as a saint is

that of his canonization initiated by the Philippine Independent

Church (PIC) or La lglesia Filipina lndepend.iezre. Founded on

August 3,1902, the PIC became a major religious sect with a

number of followers supporting its anti-friar and anti-imperialist

campaigns. As a nationalist religious institution, PIC churches

displayed Philippine flags in its altars as an expression of their

love of country and recognition of heroes who fought for our

independence (Palafox, zOtZ).

In 1903, the PIC's official organ published the "Acta de

Canonizacion de los Grandes Martires de la Patria Dr. Rizal y PP.

Burgos, Gomez y Zamora" (Proceedings of the Canonization of

the Great Martyrs of the Country Dr. Rizal and Fathers Burgos,

Gomez and Zamora). According to the proceedings, the Council

of Bishops headed by Gregorio Aglipay met in Manila on

,,

/

REMEMBERING

RIZAL 29

Scptember 24,1.903, On this day, Jos6 Rizal and the three priests

wcre canonized following the Roman Catholic rites.

After Rizal's canonization, Aglipay ordered that no masses

for the dead shall be offered to Rizal and the three priests.

'l'heir birth and death anniversaries will instead be celebrated

in honor of their newly declared sainthood. Their statues were

revered at the altars; their names were given at baptism; and, in

the case of Rizal, novenas were composed in his honor. Aglipay

also mentioned that the PIC's teachings were inspired by Rizal's

ideology and writings. One of PIC's founders, Isabelo de los

Iteyes, said that Rizal's canonization was an expression of the

"intensely nationalistic phase" of the sect (Foronda,2001,).

Today, Rizal's pictures or statues can no longer be seen in the

altars of PIC. His birthday and death anniversary are no longer

celebrated. However, it did not deter the establishment of other

Rizalista organizations.

In the 1950s, Paulina Carolina Malay wrote her observations

of Rizal being revered as a saint (Foronda,2001.,p.47):

Many towns of Leyte, drnong them Dulag, Barauen, and

Limon, haue religious sects called Banal uhich uenerate

Rizal as a god. They haue chapels where they pray on

their knees before the hero's picture or stdtue.

Legaspi City, too, has a strange society called Pantaypdntdy whose members are called Rizalinos. Periodically,

the members ualk barefoot in a procession to Rizal's

monument and hold a queer sort of a mass. Uswally, this

procession is done on Rizal Day (Decernber 30) or on

lwne 19, the natal day of the hero.

Sotne "colorrtrn" sects also uenerate Rizal as a god. A

"colorum" sect inTayabas, Qwezon has buih a chapel for

bim at the foot of Bwndok San Cristobal, better knoutn

as Mt. Banahaw...

]0

't rrE

IiTL AND WoRKS oF jostl RIzAL

The sect called Rizalirua in Barrio Calwlwan, Concepcion,

Tarlac has euen d sort of nwnnery for its priestesses. The

girls, forbidden to marry dwring a certain period, a.re sent

to Rizal's hometoran, Calamba for "training."'Wben they

go back to Tarlac, they perform mdsses, baptize and do

otber religious rites...

These observations show that Rizalistas continued to flourish

after the PIC's canonization of Rizal. Tracing the origins and

establishment of different Rizalista groups will, therefore, help

one appreciate the followers' view of Rizal's role in shaping their

socio-religious beliefs.

REMEMBERTNG

uith

RrzAL 3l

of

4.

Man is endowed

good deeds.

5.

Heauen and hell exist but are, neuertheless, "witbin us."

5.

a soul; as swch, mAn is capable

The abode of the members of the sect in Bongabon,

Nweua Ecija is the New Jerusalem or Paradise.

7.

The caues in Bongabon are the dwelling place of lehouab

or God.

B.

There are four persons in God: God, the Father, the Son,

the Holy Gbost, and the Mother (Virgin Mary).

Like the Catholic Church, the Adarnista also conducts

:;rrcraments such as baptism, confirmation, marriage, confession,

Groups Venerating Jos6 Rizal

Adarnisto or the lglesiong Pilipino

In

1901, a woman in her thirties, Candida Balantac of

Ilocos Norte, was said to have started preaching in Bangar,

La Union. Balantac, now known as the founder ol Adarnista

or the lglesiang Pilipina, won the hearts of her followers from

La Union, Pangasinan, and Tarlac. This preaching eventually

led her to establish the organization in Bongabon, Nueva Ecija

where she resided until the 1960s (Ocampo, 2011).

Balantac's followers believe that she was an engkantada

(enchanted one) and claimed that a rainbow is formed (like that

of Ibong Adarna) around Balantac while she preached, giving her

the title "lndng Adarna" and the organization's name, Adarnista.

Others call Balantac Maestra (teacher) and Espiritu Santo (Holy

Spirit).

The members

(Foronda,2001):

1.

2.

3.

of

the Adarnisfa believe in the following

Rizal is a god of the Filipino people.

Rizal is trwe god and a true man.

Rizal was not execwted as has been mentioned by

hislorians.

.rrrd rites of the dead. Masses are held every'Wednesday and

StrndaS at 7:00 in the morning and lasts up to two hours.

Special religious ceremonies are conducted on Rizal's birthday

;rrrd his death anniversary which start with the raising of the

lrilipino flag. In a typical Adarnista chapel, one can see images

.,f the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Immaculate Heart of MarS Our

Lady of Perpetual Help, and in the center is the picture of Rizal.

llcside the latter are pictures of other Philippine heroes like Luna,

[]urgos, del Pilar, Mabini, Bonifacio, etc. (Foronda,2001).

The Adarnistahas more than 10,000 followers in La Union,

Isabela, Pangasinan,Zambales, Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, and Nueva

Vizcaya, and some in Baguio City and Manila.

Sambohong Rizol

Literally the "Rizal Church," the Sambahang Rizal was

founded by the late Basilio Aromin, a lawyer in Cuyapo, Nueva

Ircija, in 1918. Aromin was able to atffact followers with his

claim that Sambahang Rizal was established to honor Rizal who

was sent by Bathala to redeem the Filipino race,like Jesus Christ

who offered His life to save mankind (Foronda, 2001). Batbala is

the term used by early Filipinos to refer to "God" or "Creator."

Aromin's group believes that Rizal is the "Son of Bathala" in

')2

t HE LrFE AND woRKS

or

JosE RrzAL

the same way that Jesus Christ is the "Son of God." Noli Me

Tdngere and El Filibusterismo serve as their "bible" that shows

the doctrines and teachings of Rizal. Their churches have altars

displaying the Philippine flag and a statue of Rizal.

Similar

to the Catholic Church, the Sambahang

Rizal

conducts sacraments like baptism, confirmation, marriage, and

ceremonies for the dead. It assigns preachers, called lalawigan

guru, who are expected to preach Rizal's teachings in different

provinces. Aromin, the founder, held the title Pangwlw guru

(chief preacher). At the height of its popularitg the organization

had about 7,000 followers found in Nueva Ecija and Pangasinan

(Foronda, 2001).

REMEMBERINC RIZAL 33

to iglesia to avoid suspicion by the Japanese soldiers

,lrrring'World'War II, making it as the lglesia.Watauat ng Lahi

(ly;t,20!2).

,lr,rrrged

The aims of the organization are as follows (Foronda, 2001):

1.

2.

3.

To loue God aboue all things

To loue one's fellowmdn ds one loues himself

To loue the motberland and to respect and uenerate

the heroes of the rAce especially the martyr of

Bagumbayan, Dr. Rizal, to follow, to spread, and to

support their right teachings; and to serue the country

with one's whole heart towards its order, progress, and

peace.

lglesia Watawat ng Lahi

:t:

Samahan ng'V/atauat ng Lahi (Association of the Banner

of the Race) is said to have been established by the Philippine

national heroes and Arsenio de Guzman in 1,911,.It was in this

year that de Guzman started to preach to the Filipino people that

Rizal was the "Christ" and the "Messenger of God." He claimed

that God has chosen the Philippines to replace Israel as his "New

Kingdom." Some believe that it was the spirit of Rizal which was

working with de Guzman telling people to live in accordance

with Christ's and Rizal's teachings (Iya,201,2).

According to stories, sometime in 1936, a banal na tinig

(holy voice) instructed Mateo Alcuran and Alfredo Benedicto to

go to Lecheria, Calamba in the province of Laguna to look for

Jovito Salgado and Gaudioso Parabuac. Alcuran and Benedicto

followed the banal na tinig and met with Salgado and Parabuac

in Lecheria on December 24, 1936. Every Saturday afternoon

from then on, the four listened to the teachings of the banal na

tinig.In 1.938,the banal na tinig informed them that their guide

was the spirit of Jos6 Rizal which instructed them to organize a

movement called the Samahan ng'Watawat ng Labi (Association

of the Banner of the Race). However, the word samahan was

Foronda (2011,) also enumerated the beliefs

lirrthered from his interviews in 1960-1,961,:

1.

of the sect

The teachings of the sect are based on the commands

Jesws Christ, and tbe

teachings of Dr. lose Rizal culled from his writings.

of the Holy Moses, Our Lord

2.

Cbristians belieue in the Trinity; the power of the Father

was giuen to Moses; the power of the Son, giuen to

lesus Cbrist; and this sect belieues that tbe pouer of the

Holy Ghost was giuen to Dr.lose Rizal.

3.

Jesus Christ is embodied in Dr.lose Rizal and hence, Dr.

Rizal is at once a god and d mdn.

4.

Rizal is not dead; he is aliue and is pbysically and

materially present in the New Jerusalem which is

presently hidden in the site extending from Mt.

Makiling to Mt. Banahaw.

5. It is tbe uoice of Rizal which commands

the officials

and the members what to do; this uoice is heard in the

weekly meetings. Howeuer, an inuoker in the person of

Gaudioso Parabwac is needed to ask Rizal to come and

talk to members.

34 l

HE I.rrr, ANr) woRKS

or

JosE RrzAr.

5. If World War lll breaks out, nwmberless

peoples will be

killed by atomic tueapons. Bwt after the war, Dr. Rizal

will make dn dppedrdnce to the new tuorld, and he will

lead the army of God.

7.

Man has a sowl, but a soul that is different from tbe

sowl of Dr. Rizal, for Rizal is god. Three days after his

death and if he was boly in life (i.e., if he followed the

commandments of God), man will rise again and his

soul will proceed to the New Jerusalem. lf he did not

fulfill the commandments of God, the soul is not to be

pwnished in hell (for there is no hell) bwt will be made

to work in a place opposite the Neru lerwsalem.

8.

There is a particwlar iudgment (the soul is judged three

days after death) and tbe last iwdgment (when all the

credtures

will

be iwdged).

lglesia 'Watawat ng Lahi is one of the biggest Rizalista

groups with more than 1-00,000 members found in different

parts of the country. FIowever, in 1987, it was divided into

three factions: (1) the Watawat ng Lahi, also known as

the Samahan ng 'Watawat ng Lahi Presiding Elders; (2) the

.Watawat

ng Labi, Inc.; and (3) the lglesia ng Lipi ni

lglesia

Gat Dr. lose P. Rizal, lnc. (Iya, 201,2). The first group now

teaches that Rizal is not Christ but only a human while the

last two groups claim that they hold the original teachings and

doctrines of the old lglesia Watawat ng Lahi-Rizal is God/

Christ himself, the loue Rex Al (God, King of All).

Supremo de la lglesio

de lo Ciudod Mistica de Dios, lnc.

Officially registered as an organization in 1.952, Suprema de

la lglesia de la Ciwdad Mistica de Dios, lnc. (Suprcme Church

of the Mystical City of God) was founded by Maria Bernarda

Balitaan (MBB) in the Tagalog region who was said to have

REMEMBTRI\:

II 1{{ZAL 35

the early 1920s. TodaS Ciudad

llrstica is the biggest Rizalista group located at the foot of

1\lt. llanahaw in Barangay Sta. Lucia in Dolores, Quezon with

.rpploximately 5,000 members in Sta. Lucia alone. All over

I rrzr)n, it has about 100,000 members.

'.r;rrrcd her spiritual missions in

In the history of Ciudad Mistica's establishment, the group

woman. Its leader is called the Swprema

rvlrr assumes the responsibilities of assisting members seeking

.r..lvice, resolving conflicts among members (including legal

, onflicts), and making major decisions in the organization.

lr,rs :rlways been led by a

The members believe that as a result of endless conflicts

.unong countries in West Asia, God decided to transfer His

"l(ingdom" to the Philippines. It explains why there existed

"lroly stations/altars" (locally called pwesto) in Mt. Banahaw,

rvhich is equivalent to the stations of the cross of Christ in the

l\syon (Ocampo, 2011).

For the Ciwdad Mistica,Jesus Christ's work is still unfinished

,rrrd it will be continued by Dr. Jos6 Rizal and the "twelve lights"

,rI the Philippines composed of the nineteenth century Philippine

lrcroes. These "twelve lights" are said to be the equivalent of

f csus Christ's twelve apostles. Their work will be fulfilled by a

woman, in the person of MBB, as can be seen in their hymns

(Quibuyen, 1991.):

The Virgin Maria Bernarda, a Filipino motber

Dr. Jose Rizal, a Filipino father

Once in d mystery, they came togetber

And so, emerged this country, the Philippines.

Like the other Rizalista groups, the Ciudad

Mistica

shares many elements with the Catholic Church. They hold

rnasses (every Saturday), and have prayers and chants. They

commemorate the birth and death anniversaries of the "twelve

lights," with Rizal's death (December 30) as the most important

celebration. Each commemoration starts with the raising of the

Philippine flag.

36

'l'HE LrFE AND woRKS oF Josf, RIZAL

REMEMBERTNG

RrzAL 37

llLrbric

Chapter Questions

rrli::r:irlt:l:llir:::ll{i

Briefly answer the following:

Few or none of

the statements are

All statements are

supported by the text.

1,. How do Rizalista groups view Jos6 Rizal and other

supported by the

text.

national heroes?

All statements noting

similarities are placed

in the center circle and

all statements that note

differences are placed

in the correct outer

circle.

withl.l,,,i:'ii::,rl:,l:tll

the

e

2.

'What are the similarities between

Jesus Christ and Rizal

groups?

as seen by the millenarian

Vei'h:,::r:tiri:ti

Ia^;i*il:::l:illl::1,

Student is able to make

5 or more comparison

statements in each

circle.

Num,b€f:r;:t:

of qiiiLti,lr,

Most statements

are placed in the

correct circle,

but student has

mixed up a few

statements.

Few statements

are placed in the

correct circle.

Student is able

Student has

made only 2 or

fewer comparison

statements in each

circle.

to make 3-4

comparison

statements in each

circle.

';ource: lnternational Reading Assoclation/National Council of Teachers of English. (2007). Venn

( liagram rubric. Available from http://www.readwritethink.org/flles/resources/lesson*images/

54ldetectiverubric.pdf

l(.sson

3.

Name some influential women in various Rizalista

groups and explain their significant roles in their

respective organizations.

Venn Diagram

Form yourselves into groups of five members. Then, make a

.5- to 10-minute audio-visual presentation on one Rizalista group

rrsing photos of the churches, altars, and celebrations/activities of

the group. Also look for other information not mentioned in the

cliscussion. Present your work in class.

Il u bric

ir.:,,8ii!4

Choose two of the Rizalista groups, that were discussed. On

a separate sheet of paper, create a Venn diagram showing the

beliefs and practices that are similar and different between the

two groups. Afterwards, rate yourself according to the rubrics

that follow

Presentation shows

Cont€iiali:r:].:ir,:rr:li:'

. .a .a,.' .a::..',::)',;a:.:

:

.i

.:

:::.aa:

:'.::.:

t:..:'t::

.::::.

,'i ,l:i,..lil,ll ,lll:lll,l:ll

]ir,:i:.,t:r:til,::ii::,,,t:r

r

rrtr::, r:,t.rtrt,,:t.

t:,t:.t:trt

l

full knowledge

by providing

interpretations and

analysis; complete

with photos and

illustrations from

research.

Presentation shows

some knowledge;

lacks interpretation

and analysis; has

incomplete photos

and illustrations.

Presentation

lacks important

information;

no substantial

interpretation and

analysis; has no

photo or illustration.

38

'fr-n: LIFE ANII woRKs oF JoSi, RIZ-AL

Video information

is logical; has

sequence which

the class can easily

follow.

Presentation has

high quality photos

and audio.

REMEMBERING

The cl6ss cannot

follow the sequence

because the

presentation jumps

from one theme to

another.

The video has no

clear narrative line.

Some photos and

audio need editing.

Photos and audio

are not clear making

the video difficult to

understand.

R,IZAL 39

Etbics, Religion and Philosophy (ACERP). Osaka, Japan.

on March 23,2017 from https://www.academia.

e dul 9 0 8 37 64{ove_Rex_Al_The_Making_of_Filipino_Christ

Accessed

Mcrcado, Leonardo V., SVD. 1982. Christ

in the Philippines.

Tacloban City, Philippines: Divine 'Word University

Publications.

()campo, Nilo. 2011. Kristong Pilipino: Pananampalataya kay

Jose Rizal. Quezon City: Bagong Kasaysayan.

l'alafox, Quennie. 2012. "Rizal: A hero-saint?" Accessed on

March 24, 2017 from http:l lnhcp. gov.ph I jose-rizal-a-heroThis chapter showed that Rizal is not only regarded as the

Philippine national hero but also venerated as the "Filipino

Jesus Christ" or the Joue Rex A/ (God, King of All) by most

Rizalista groups. The canonization of Rizal by La lglesia Filipina

Independiente and the eventual emergence of Rizalista groups

in different parts of the country could be associated with the

long struggle of the Filipinos for freedom and independence.

Syncretism is also evident among the Rizalista groups as the

nationalist visions are included in their religious beliefs and texts.

Covar, Prospero. 1.998. Larangan: Semindl essdys on Philippine

cwlture. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the

Arts.

Foronda, Marcelino A.,Jr.2001.. Cults honoring P.izal. Historical

Bulletin (5Oth Anniversary Issue): 46-79. Manila: National

Historical Institute.

Ileto, Reynaldo. 1998. Rizal and the Underside of Philippine

History. In Filipinos and their reuolution: Euent, discowrse

and historiography, pp. 29-78. Quezon City: Ateneo de

Manila University Press.

Iya, Palmo R. 2012. "Joue Rex Al: The Making of Filipino

Christ." Paper presented in The Asian Conference on

saint/

(luibuyen, Floro C. 1991. And woman will prevail over man:

Symbolic sexual inversion and counter-hegemonic discourse

in Mt. Banahaw, The case of the Ciudad Mistica de Dios.

Philippine Studies Occasional Paper No. 10. Cenrer for

Philippine Studies, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

I'rillana, Pablo S., III. 2006. Rizal and heroic traditions: A sense

of national destiny. Other essays and bometown stories.

Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

THE LiFE

chinese mestizo

CHAPTER 4

-

or

JosE

RrzAL 4l

a person of mixed Chinese and Filipino ancestry

prlncipalio - the ruling and usually educated upper class in Spanish

olonial Philippines

,

THr, Ltpr,

oF ]osE Rrzel

Bochiller en Artes

-

Bachelor of Arts degree bestowed by colleges or

rrrriversities

sponish Corfes

llustrodo

-

-

Spain's lawmaking or legislative body

a term which literally means "enlightened ones" or the

I ilipinos educated in Europe

Masonry

-

fraternal organization which strives for moral betterment

Rizal's Family

biography narrates how a person has lived during a certain

period of time. lt presents not only the life of an individual

and how he/she has influenced the society but also how an

individual and his/her ideas have been shaped by historical events.

Jos6 Rizal lived in the nineteenth century, a period in Philippine history

when changes in public consciousness were already being felt and

progressive ideas were being reaiized. Studying Rizal's biography,

therefore, will lead to'a better understanding of how Rizal devoted his

life in shaping the Filipino character. This chapter will cover Rizal's life

and how he became an important hero of the Philippines.

At the end of this chapter, the students should be able to:

,P

P

?

A

discuss about Rizal's family, childhood, and early education;

describe people and events that influenced Rizal's early life;

explain Rizal's growth as a propagandist; and

identify the factors that led to Rizal's execution.

Jos6 Rizal was born on June L9, 1.861 in the town of

(,:rlamba, province of Laguna. Calamba, then a town with

.rround three to four thousand inhabitants, is located 54

l<ilometers south of Manila. It is found in the heart of a region

Inowfl for its agricultural prosperity and is among the major

1',roducers of sugar and rice, with an abundant variety of tropical

lruits. On the southern part of the town lies the majestic Mount

Makiling, and on the other side is the lake called Laguna de Bay.

l'he wonders of creation that surrounded Rizal made him love

nature from an early age. His student memoirs show how his

Iove of nature influenced his appreciation of the arts and sciences

((loates, 1992).

Rizal's father, Francisco Mercado, was a wealthy farmer

who leased lands from the Dominican friars. Francisco's

t'rrrliest ancestors were Siang-co and Zun-nio, who later gave

birth to Lam-co. Lam-co is said to have come from the district

of Fujian in southern China and migrated to the Philippines in

tlre late 1600s. In 1,697, he was baptized in Binondo, adopting

"l)omingo" as his first name. He married Ines de la Rosa of a

42

THE LrrE AND WoRKS

THE LIFE OT JOSE RIZAL 43

or Josf RIZAL

known entrepreneurial family in Binondo. Domingo and Ines

later settled in the estate of San Isidro Labrador, owned by

the Dominicans. In 1,731, they had a son whom they named

Francisco Mercado. The surname "Mercador" which means

"marketr" was a common surname adopted by many Chinese

merchants at that time (Reyno,2012).

Francisco Mercado became one of the richest in Biflan and

owned the largest herd of carabaos. He was also active in local

politics and was elected as capitan del pweblo in 1,783. He had

a son named Juan Mercado who was also elected as capitdn del

pueblo in 1808, 1813, and 1823 (Reyno,2012).

Juan Mercado married Cirila Alejandra, a native of Biian.

They had 13 children, including Francisco Engracio, the father

of Jos6 Rizal. Following Governor Narciso Claveria's decree in

1849 which ordered the Filipinos to adopt Spanish surnames,

Francisco Engracio Mercado added the surname "Rizal," from

the word "ricial" meaning "green fieldr" as he later settled in

the town of Calamba as a farmer growing sugar cane, rice, and

indigo.

Being in a privileged family, Francisco Engracio (1818-1898)

had a good education that started in a Latin school in Biflan.

Afterwards, he attended the College of San Jose in Manila. In

1,848, Francisco married Teodora Alonso (1826-L9ll) who

belonged to one of the wealthiest families in Manila. Teodora,

whose father was a member of the Spanish Cortes, was educated

at the College of Sta. Rosa. Rizal described her as "a woman of

more than ordinary culture" and that she is "a mathematician

and has read many books" (Letter to Blumentritt, November 8,

1888). Because of Francisco and Teodora's industry and

hardwork, their family became a prominent member of the

principalia class in the town of Calamba. Their house was among

the first concrete houses to be built in the town. Rafael Palma

(1,949, p. 1), one of the first biographers of Jos6 Rizal, described

the family's house:

The house was high and euen sumptuous, a solid and

massiue edrthqudke-proof structure utith sliding shell

windows. Tbick walls of lime and stone bounded the

first floor; the second floor was made entirely of wood

except for the roof, which uas of red tile, in the style of

the buildings in Manila at that time. Francisco himself

selected tbe hardest woods from the forest and had them

sawed; it took him more tban two years to construct the

house. At the back there was An d.zotea and a wide, deep

cistern to hold rain water for home wse.

Jos6 Rizal (LS6L-1.896) is the seventh among the eleven

children of Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso. The other

children were: Saturnina (1850-1913); Paciano (1851-1930);

Narcisa (1852-1,939); Olimpia (1855-1887); Lucia (L85719191; Maria (L859-1945); Concepcion (1862-1865); Josefa

(1865-1945); Trinidad (1868-1951); and Soledad (1.870-1.929).

to all his

siblings. However, his