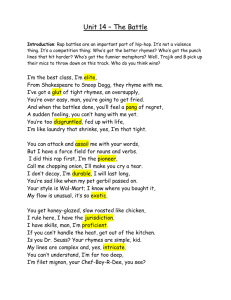

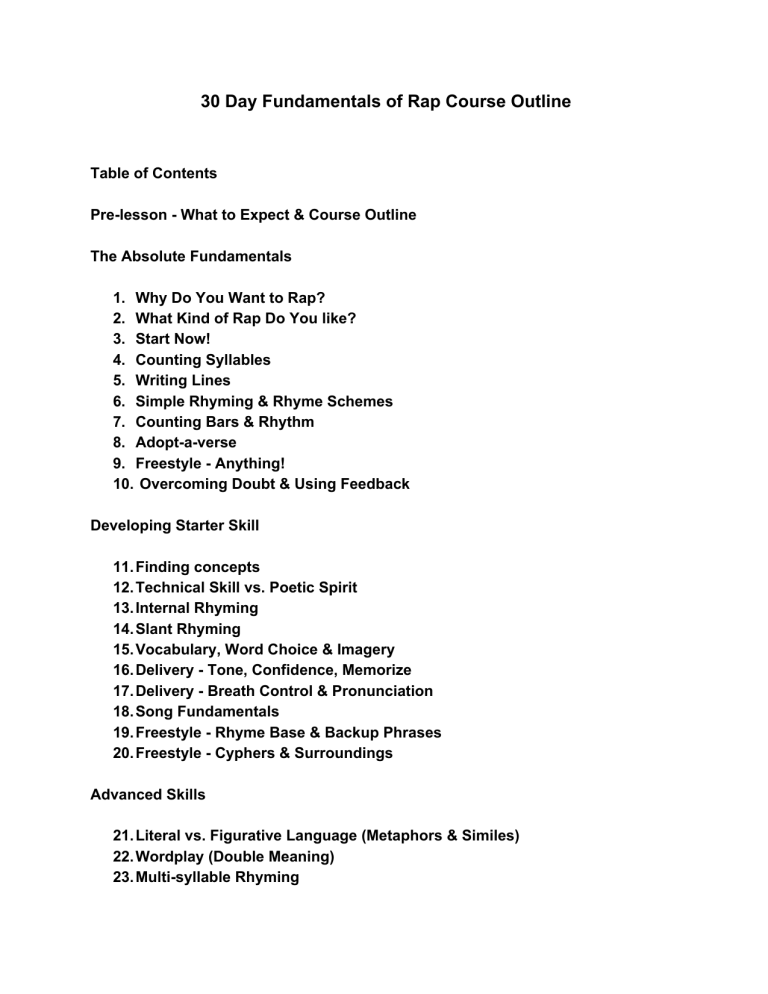

30 Day Fundamentals of Rap Course Outline Table of Contents Pre­lesson ­ What to Expect & Course Outline The Absolute Fundamentals 1. Why Do You Want to Rap? 2. What Kind of Rap Do You like? 3. Start Now! 4. Counting Syllables 5. Writing Lines 6. Simple Rhyming & Rhyme Schemes 7. Counting Bars & Rhythm 8. Adopt­a­verse 9. Freestyle ­ Anything! 10. Overcoming Doubt & Using Feedback Developing Starter Skill 11. Finding concepts 12. Technical Skill vs. Poetic Spirit 13. Internal Rhyming 14. Slant Rhyming 15. Vocabulary, Word Choice & Imagery 16. Delivery ­ Tone, Confidence, Memorize 17. Delivery ­ Breath Control & Pronunciation 18. Song Fundamentals 19. Freestyle ­ Rhyme Base & Backup Phrases 20. Freestyle ­ Cyphers & Surroundings Advanced Skills 21. Literal vs. Figurative Language (Metaphors & Similes) 22. Wordplay (Double Meaning) 23. Multi­syllable Rhyming 24. Battles & Punchlines 25. Storytelling 26. Developing Flow 27. Freestyle ­ Rhyming Ahead & Using Beats 28. Freestyle ­ Opposites & Themes 29. Finding beats & Recording 30. Putting it all together Pre Lesson: What to Expect & Course Outline Congratulations on taking the first step toward learning how to rap! Simply reading this sentence shows you are motivated enough to start learning. You may know nothing now, and that is perfectly fine. By the end of this course you will understand the fundamentals of rap and be prepared to write, record, and freestyle. Even if you know how to rap already, reviewing the fundamentals is still useful as practice only improves your skills. Let's get started. This course is designed to help you tap into your potential and develop a tool set to create rap music. There is no right or wrong in art, only a set of tools you can use. This course is not designed to make you famous, or to tell you exactly how you should rap. It is simply about the core components of rap, and how to start developing your talents as an artist. This course is broken up into three sections, each consisting of ten short lessons. Each section includes progressively difficult concepts with each lesson building upon previous lessons. Completing these lessons in order is essential as you work through the course, otherwise you may get confused. I have also prepared at least one exercise for each section. I strongly encourage you to complete these assignments, as they will help you understand the concepts as well as provide practice in building the skills you need to master the fundamentals. There’s three major components covered in this course. The personal aspect, the written aspect, and the musical aspect. Each section contains lessons in each aspect and all these aspects work together as a basis for creating music. It may seem odd to combine topics like personal growth, self­esteem, and motivation with others like rhyming and flow but these are all important aspects of developing as an artist. The sections are broken down as follows: Section 1 ­ The Absolute Fundamentals Section one is focused on the most essential skills you’ll need to start rapping. These skills are the building blocks of all the future lessons and extremely important. After completing this section you should have an idea of the structure of rap and the basics of writing and rap music. Section 2 ­ Developing Start Skill This section focuses a lot more on techniques that you’ll need to elevate your rap style. Instead of writing basic, standard verses, this section will show you what you can do to make your rap more engaging and developing your vocals. After completing this section, you should feel comfortable delivering and writing verses. Section 3 ­ Advanced Skills This section focuses on the more advanced skills you need to really stand out as a rapper. Some of these are extremely difficult and can take a long time to master. Once you complete this section, you should feel very comfortable freestyling, writing, and recording rap music. You should also have an idea of what skills you’d like to work on moving forward. Exercise: I’ve tried to make these lessons fairly short, so I recommend setting a time in your schedule to work on them. Having a scheduled time increases your commitment and makes it more likely you will finish the course. It also helps you get in the habit of practicing consistently because, as with any talent, it takes lots of practice to develop the skill. The Absolute Fundamentals Day 1: Why Do You Want To Rap? Today we’re going to focus on a personal aspect. Personal aspects involves knowing who you are, what you want, the direction you're going, and how you are going to accomplish your goals. By better understanding yourself it becomes easier to get in touch with your talents and desires. We will start by taking some time to reflect on why you want to rap. Consider what you hope to accomplish by the end of this course. The longest lasting motivations are internal, like mastery or growth. If you are rapping solely because you want to become rich or famous, you may lose your love for the craft if you ever reach that point. These are desires that can only be achieved externally, and somewhat out of your control. Looking externally also pushes an agenda for your music as many artists attempt to create what they think is popular, instead of a true representation of themselves. Being genuine and creating art that is a representation of yourself and your experiences has always been important in rap music. When you allow yourself to escape expectations and truly focus on what issues are important to you, the quality of the art increases. It also just feels better. Now don’t get confused here, I’m not saying you have to be literal all the time and act exactly the same as you do during your normal life, I’m just saying that you need to find a way to make the art your own, instead of letting what you think you should be making mcontrol you. Using external metrics for success may not correlate with your actual progress as they must be validated by others. For this course, we will be emphasizing the process of becoming a better artist instead of the product. If you focus on a process for growth and develop underlying skills, the product will undoubtedly improve. Exercise: Close your eyes for a few minutes and think about what rap means to you. Your personal experience with the art so far, how it has influenced you. Think about why you want to learn to rap, what you want out of this course and how it can benefit you. Think about your dreams and goals as an artist. Write down these thoughts. You can use as many or as few paragraphs as you need, the goal here is to take a serious look at rap and where it fits into your life. Maybe it's simply a hobby to pass time. Maybe it's your way of fighting injustice in the world. Maybe it’s completely foreign and you want to try something new. Whatever your motivations and aspirations are take time to articulate the purpose of rap in your life right now. I'm looking forward to reading what you write. Worksheet: Here’s a few questions to help guide your thought process, write out your answers to each question. 1. Why do you want to rap? 2. What role does rap play in your life? 3. What do you hope to get out of this course? Example: 1. I originally wanted to learn to rap because of battles. I’m naturally a very competitive person and I wanted to show I could beat other people. I’ve have always listened to rap music and was drawn to the wordplay and clever punchlines in battle rap. 2. Rap eventually came to fill a very different role. It now allows me to express myself and release negative emotions. I find myself so caught up with little problems in my life sometimes I let them consume me. Rap is a way to release the negative energy. I also have a deep fascination with clever lines and wordplay and rapping allows me to interact with them in ways I otherwise couldn't. 3. I hope that this course will give me the opportunity to polish my fundamentals even further. With each lesson that I write, I am forced to come up with examples and ensure that I know the concept inside and out. If I run into any concepts that I have a hard time explaining, I must do extra research and learn more until I can find a way to teach the concept. Doing this both makes me feel like I’m doing something productive, as well as improves my skill in the craft. Day 2: What kind of rap do you like? Content: Now that you know why you want to learn to rap, the next step is to figure out what aspects of the art really capture your attention. The parts which drive your interest and got you here. The easiest way to figure out what you like is to determine which artists you admire most and then break down the skills they excel at. By deeply examining other artists, we can get an idea of what we love and the kind of art we would like to create ourselves. Naturally, each rapper has various strengths and weaknesses, just like any sport or art. Even the greats excel at certain skills more than others. These different combinations of talents will, of course, appeal to different audiences. The focus today is to figure out which combinations appeal to you and where you would like to fall in the spectrum. Are you more drawn to lyricism? Or to heavy beats and fast tempos? Do you hate awkward word play? Or love it? Ask any rapper who their favorite artists are and a few of their favorite songs and they'll be able to name them immediately. Why? Because we all have influences that we use to guide ourselves. By examining other artists you can simultaneously learn about what you like and dislike, while getting a firsthand view of how an established artist utilizes these techniques throughout their songs. Listen carefully and you can pick up ideas as to how they use their skills together to create their music and learn for yourself. The aspects of rap are not a roadmap, but a painting. There is no certain set of skills you must develop. You are in control of what areas you want to focus on and develop and what other areas you spend less time with. You are in control of the style you want. Over time this will likely evolve, but having a goal makes the path easier. That is why we are talking a day to develop an idea for that path. Oh and if you're antsy to get started writing and rapping, don't worry, that starts tomorrow. Exercise: Write down 2 of your favorite rappers and what you like about them. Write down a list of the skills you envy. I want you to focus on them, listen to lots of their songs. Focus on how they work on their craft. I also want you to pick 2 rap songs from established artists to start memorizing. I strongly recommend you do this as it will come in handy later in the course. Worksheet: 1. What aspects of rap do you like? 2. What aspects of rap do you dislike? 3. Who are your favorite rappers or biggest influences? A. What do you like about them? B. What do you dislike about them? 4. What albums or songs are you going to listen to today to start drawing from? 5. What songs are you working on memorizing? Example: 1. Likes: Lyricism, changing flows, storytelling 2. Dislikes: Nonsensical lines, repetitive lyrics, incomprehensible delivery 3. Eminem is one of my biggest influences. The way he manipulates lyrics with rhyme schemes is undoubtedly one of the best to ever do it. I also like how he is able to let loose with his delivery, though sometimes I feel his content is a little obnoxious and disgusting just for shock value. Another one of my main influences is Slug from Atmosphere. Slug has a fantastic way of walking the border between complex and relatable. I also like his ability to weave story lyrics into his songs. I don't like that his flow patterns and delivery are very limited, he rarely travels outside of his established routines. Extra Credit: I also want you to try another exercise that you may not be comfortable with today. I want you to listen to rap music you actually dislike, and actively search for things that you like about it. I want you to look for things other people may like. This may never be music that you want to create, but by at least observing a wide range of music you open your mind to more possibilities. Day 3: Start Now! Content: A big part of this course is going to be about breaking past your insecurities and unleashing your creativity. Although this isn’t the case with everyone, the hardest part for many individuals is being comfortable with their own work. You may be afraid others will judge you, put you down, and ridicule your art. It can be a painful experience to get negative feedback but it really is essential to growth. So, while you may not receive praise for every piece you create, the positives of sharing your work far outweigh the negatives. Let’s do a quick thought exercise about what happens when you put your work into the world. Here is a list of pros and cons for releasing a new piece: Pros: Receive feedback that helps you improve, gaining a new fan, creating a piece that really resonates with someone and improves their life, find someone who is interested in collaborating in the future. Cons: Receive feedback that hurts your feelings, creating a piece that people have trouble relating to. When you take a minute to really consider these options, there is nothing to lose by sharing your work. You cannot let those out there who will potentially dislike your work ruin it for those that will love it. Even the most established artists, with gigantic fan bases, have individuals out there who believe their music is awful. Find a strong center of confidence and push forward. There’s two main types of insecurity that most people run into with rap music; one is writer’s block, the other is being uncomfortable with your voice. I’m sure insecurities take other forms but these are the two I have seen the most. Just remember, anything you struggle with stems from lack of confidence or lack of practice. Some things you can improve through effort while others you simply need to give yourself respect. Let’s start with writer’s block. One of the biggest causes of writer’s block is over­thinking instead of letting the process flow through you. Once you start writing, you break free from perfectionism and move into the workflow essential for creating. Next time you experience writer’s block, take a few minutes to relax and remove any self­judgement. Then start putting words down, even if it is complete gibberish. It’s ok if you don’t write a masterpiece. It’s ok if you don’t like a particular piece you put together. Many times you’ll actually be happily surprised with what you produce, and you can always go back and make edits later. The more you practice, the more you develop your skills and that’s really what the process is all about. I still make songs and write verses that I’m not happy with. The key is accepting your own work for what it is, and moving on. You may also think your voice isn’t right for rap and this paralyzes you from speaking. You must learn to love and embrace your voice. There are techniques you can use to modify your voice and improve delivery, but it will always be your voice. Many people are fundamentally uncomfortable with the sound of their own voice, regardless of what it actually sounds like. This doubt can crush your confidence, which will certainly show in your delivery. Here’s the truth of it though; anyone with any kind of voice can become talented enough to make good rap music if they practice enough. Worries about my voice was my biggest roadblock in learning to rap. When I started, I got a huge amount of negative feedback about my voice and delivery. I quickly started to believe I would never be able to make music anyone would like. It hit me hard, I practically stopped making music. I couldn’t leave rap alone though and eventually I hit a point where I stopped caring what others thought. I figured no one would ever like it, and that was fine, as long as I got to practice the art I loved. As soon as I decided to let loose and accept my voice, I started receiving support. People could hear the change in my confidence, and that’s all it took. As you move forward, forget about what your voice naturally sounds like, and focus on the things you have control over. I promise you can reach your goals. Today’s exercise is a focus on building self­esteem and freeing yourself from the paralyzing force of perfectionism. The worst case scenario is that you create works that no one else in the world likes. This has no real impact on your life, it’s not going to ruin you. Opinions have no bearing on who you are as a person. Negative feedback might sting, but you can always move forward from that, and more likely than not you’ll actually receive a lot of support from others for having the courage to step out of your comfort zone and produce something. Many others do not have the strength to create and share a work of art, be that brave person who is willing to put their creativity on display, and you will almost certainly be proud of yourself in the future. Exercise: Start writing, anything. Don’t stop until you fill up a page. Do not go back and edit it, do not change anything, do not stop writing. Then read it aloud. Not in a boring, monotone voice, but read it like it’s important. Like you are in love with it. Give it all the emotion and power your piece deserves. You might think you sound stupid, do it anyway. Stop focusing so much on the outcomes, and focus on the process. Once you are able to lose yourself in the art, it really won’t matter what feedback you get from others, you’ll feel strength in simply creating. Worksheet: 1. Write enough to fill an entire page. 2. Read and record what you’ve written. Supplemental Material : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vnsF0IaYjk0 Day 4: Counting Syllables Content: Counting syllables is one of the most fundamental skills you’ll need when learning to rap. Many of you will already know how to do this, but I want to make sure to cover this vital skill for anyone who struggles with it. Counting syllables is the cornerstone for adjusting line length and breaking up words for more complex rhyming. Let’s start with what a syllable is. Syllables are basically units of sound within a word when pronounced aloud. When you break a word apart, syllables are the different sounds you hear within it. For example the word ‘dog’ is one syllable and the word ‘candy’ is two. Why is candy two and dog one? It’s because there is only one sound unit in the word dog, ‘dog’. There are however two sound units within the word candy, can+dee. Here are some more examples: Shotgun = 2, shot+gun Impossible = 4, Im+pos+si+ble Flag = 1, flag Expand = 2, ex+pand Tension = 2, ten+shun Lets go over a few strategies you can use to help you count syllables. The most effective for me is a combination of what’s called the robot strategy and the chin method. Essentially, pick a word, while placing your hand below your chin. Now say that word like a robot, slow and drawn out, and count the number of times your chin drops. This should equal the number of syllables in the word. Another method is the clapping strategy. To use the clapping strategy, clap along with each sound unit you hear in the word and count along with it. There is also the vowel sound strategy. Count how many times you hear a separate vowel emphasized (a,e,i,o,u). That will be the same as the number of syllables in the word. Once you have mastered the ability to count syllables for a single word, you’re going to want to start counting lines so you know how many syllables in a are in a line. Tomorrow we are going to expand on this, so make sure you understand how to count syllables. For example: I walk the line and never get lost = 9, I+walk+the+line+and+nev+er+get+lost That’s ridiculous = 5, That’s+rid+ic+u+lous He will need therapy after that one = 10, he+will+need+ther+a+pee+aft+er+that+one Exercise: Here’s a few words and sentences to practice with so you can get some practice in counting syllables. Pelican Elephant Immeasurable Flat Parse Elegant Rough Liquid I ran that woman off the road Let’s not talk about this Are you teaching us to rap? Exquisite dolphins don’t exist Eliminate the weaker people Post the answers the next day Answer Key: Pelican, 3 = Pel+I+Can Elephant, 3 = El +Eh+Fant Immeasurable = 5, Im+meas+ure+uh+ble Flat = 1, flat Parse = 1, Parse Elegant = 3, el+eh+gant Rough = 1, ruff Liquid = 2, lick+quid I ran that woman off the road = 8, I+ran+that+wo+man+off+the+road Lets not talk about this = 6, Lets+not+talk+uh+bout+this Are you teaching us to rap? = 7, are+you+teach+ing+us+to+rap Exquisite dolphins don’t exist = 8, Ex+quiz+it+dol+phins+don’t+ex+ist Eliminate the weaker people = 9, el+im+in+ate+the+weak+er+peep+el Worksheet: 1. Write 3 words, then write their syllable count. 2. Write 2 phrases, then write their syllable count Day 5: Writing Couplet Lines Content: Today I want you to focus on structuring lines into couplets. A couplet is a pair of lines that go together. Typically, couplets rhyme at the end and have the same meter (rhythm). Rap music is typically written in a couplet style. Although many artists do not strictly follow this practice, it is an easy place to for beginners to start. I also want to go over how many syllables lines usually contain. A rough guide for number is 10­16 syllables per line, however you can easily go above or below that by speeding or slowing down your delivery, which is something we’ll get to later. Since you are just starting out use the 10­16 rule as a guideline, as that’s what will easily fit most instrumentals. For our lesson today we’re going to write couplets with similar syllable length (I hope you learned to count syllables). Now in practice rap couplets don’t need to be exactly the same number of syllables, but if they are it will be easier to keep your flow steady as a beginner. That’s why we are going to practice it. Example: A. Similar My name is Dono, I’m the best in the business (12) They ask what is this? I let em be a witness (12) Get every girl in the place to trace her digits (12) So when I run game they know it’s not for fitness (12) B. Different I said hey do you want to join the squad I rock (12) No way, get off the block (6) To keep the B couplet in rhythm you either have to stretch the pronunciation or leave a large pause. Either of which is totally acceptable in the long run, but for most people it’s easier to keep the flow when the syllable count is similar. Once you are comfortable with the basics of this idea you can move on to other strategies. Exercise: I want you to practice by writing at least 8 lines with the same syllable count. For this exercise, you do not have to rhyme, although if you’re ready and feel comfortable I would encourage adding rhyme to the end. Recite the lines aloud and get a feel for how keeping them together makes it easier to keep the same rhythm. Then I want you to write a couplet with syllable counts that are totally different then recite them and see how hard it is to keep the rhythm smooth. Worksheet: 1. Are these lines equal syllables or not? Give syllable counts. Too often I drop bombs to ruin entire cities (13) The breath in my chest is the blueprint for fire spitting (13) Until death I mesh words with wild whipping (10) The best with complex text want the world to smile with me (13) Told em to try forgiving, but the anger is too real (14) Overwhelmed by emotions you feel (9) Daily practice to the task is how to develop true skill (15) If you don’t dedicate your mental state to it then who will? (15) 2. Write your own 8 lines and include syllable counts at the end. Day 6: Perfect Rhyming & Rhyme Schemes Content: Almost everyone understands how perfect rhymes work, but I want to cover them just in case. Perfect rhymes occur when the first sound or letter in a syllable is different, but the remainder of the syllable is the same. For example: Dog/Hog or Hat/Bat. The first letter is different and rest of the sound is the same. The same concept applies if you are using words with multiple syllables, just focus on the last syllable. An example would be explode and erode. Ex­pl(ode)/e­r(ode). These words are perfect rhymes because the last syllable in the words have the same ending sound. Let’s move on to something you may not understand as well, rhyme schemes. Rhyme schemes are essentially ways for you to map rhymes into your verse. There is no certain rhyme scheme you need to use, just different variations and combinations of rhyme schemes that are possible to use. The most simple rhyme scheme would be: …..A …..A This means the within the two lines, the words (indicated by the letter A) rhyme. Here is an example of what A/A would look like I move quickly no one could ever catch **up** (.....a) Tired, so I drink all the liquid in my **cup** (.....a) Notice how those are the only words in the lines that rhyme. That rhyme scheme would be shown as …...A …...A Now let’s try something a little more complex Quick as a **pup** no one could ever catch **up** (.....A…...A) Tired so I drink all the liquid in my **cup** (.......A) Because all three of those words rhyme with each other, this rhyme scheme would be shown as: …...A…….A …………...A But what if you are using other sets of words that also rhyme, but not with the original set of rhymes? In that case you use another letter to show words that are rhyming with each other, but are different from the ‘a’ rhymes. *Quick* as a **pup** no one could ever catch **up** (B…..A…..A) *Lick* every drop of liquid in my **cup** (B………..A) These scheme would be shown as: B…...A….A B………...A To help clarify, I’ve added the dots to show where the words fall, but those are not included always. Most commonly these schemes would look like the following: BAA, BA. Here, the comma denotes a new line in the verse. You can add more and more rhymes into the schemes until they are really complex. I want you to focus on understanding the basics, but here’s an example of what a more complex scheme might look like: All people want to walk on the edge of the earth (AB….C) (12) Call evil their sole parent at birth to find mirth (AB….C...C) (12) I can’t think of any single curse that is worse (...D…...C...C) (12) Meet the brink of truth in any verse; then it hurts (...D…..C...C) (12) This scheme would like like this: AB…..……..C AB…....C….C …..D.....C….C …..D.....C….C or this ABC, ABCC, DCC, DCC This will become more important when we move on to internal rhyming, slant rhyming, and multi­syllable rhyming. So take some time to understand what rhyme schemes are and how they work so that when we get to those concepts they come easier to you. Again, there is no specific scheme or order you must use. Think of schemes like colors in a painting. There's no certain colors you must use, you can just see what colors have been used and describe them. You can scheme however you want, it's more of a map than a set of rules. Here is another way to break up your schemes: Run (A) to the fit (B) cat (C) Stun (A) when I spit (B) that (C) or Run (A) it (B) like this cat (C) Stun (A) when I spit (B) that (C) Both are ABC, ABC or A.......B....C A....B.......C Exercise: For today’s exercise I want you to pick three words and write down as many rhymes as you possibly can for them (here’s three if you can’t think of any Fly, Kill, Lose). After you have those lists, use them to write 16 complete lines that end in rhymes (remember to keep the syllable counts close). Use the following scheme and your list of words to complete this: A, A, B, B, A, A, C, C or ………...A ………...A ………...B ………...B ………..A ………..A ………..C ……...C For your second 8 lines, you can write whatever you want but I want you to tell me what scheme you have used. You can put it in either format. Worksheet: 1. Pick 3 words and write rhymes for them 2. Use them to fill this scheme: A,A,B,B,A,A,C,C 3. Write 8 lines, show the schemes you’ve used 4. Identify the schemes in the following lines: My mind (A) can’t seem to find (A) the right (B) reaction (C) To answer questions your eyes (A) might (B) be asking (C) Never wanted (D) to lie (A), I just like (B) the fashion (C) And that’s what haunted (D) me, find(B)ing passion ( C) AABC,ABC,DABD,DB We danced across the ocean doing the moon (A) bop (B) You stop(B)ped to take a moment on your own(C) thoughts (B) Didn’t show (C) it, so I didn’t slow (C), you were blown(C) off (D) Desperately missing the timid touch that was so (C) soft (D) AB,BCB,CCCD,CD Supplemental Material : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYa36pKCHkQ Day 7: Counting Bars & Rhythm Content: Counting bars is another essential skill. First, let’s go over what a bar is. A bar is a measure of music, which for rap is typically done in a 4/4 time signature. What that means isn’t particularly relevant for this course, the part you need to know is that rap music almost always contains 4 counts per bar. So why do we want to count bars? Counting bars allows you to get a feel for flow, where you can place lyrics, and development of rhythm. It also lets you know exactly how much space you have to work with in the song. You can also sub­divide the bars to create a road map for filling it with lyrics in something called a flow diagram, which we will cover later. Knowing how to count bars will also help with your freestyles. It is a cornerstone to many extremely important audio skills. Now how do you count bars? Remember that there are four counts per bar. Many of you will be able to feel the rhythm in the song and bob your head along with it. This should be a steady count that correlates to the pulse or rhythm of the song. Then, to count bars you go along with the music and count 1, 2, 3, 4. When you get to 4, that would be the end of the bar. This count can be faster or slower depending on the tempo of the song. If this is difficult for you make sure to watch the videos provided below as there are audio examples. You can also use a metronome to help you. A metronome is a device that you can set to a particular speed and will create a steady rhythm. A metronome will always keep time, and you can use it to see if your counts match by setting it to the same BPM (beats per minute) as your instrumental. When counting bars is that it’s common practice to count up the first number as you count bars. What I mean is this, if you were counting bars you would do it like this: 1, 2, 3, 4 (that’s one bar) 2, 2 ,3 ,4 (that’s two bars) 3, 2, 3, 4 (that’s three bars) 4, 2 ,3, 4 (that’s four bars) As you can see, the first number in each count shows what number of bar you are on. Verses are typically written in multiples of 8 bars, most commonly 16. That’s why you hear people say things like “spit a 16” what they are referring to is 16 bars. In addition, the most basic formula for rapping has end rhymes that drop on the 4 count. Again, there is a lot of variation on how you can do this, but historically the fourth count will contain a rhyme word that matches another line to form a couplet. Getting a good grasp on counting bars builds the foundation for flowing and feeling where words can fit. Some people get confused about how many lines fit in a bar. There is no set number of lines in a bar, because a bar is a measure of time in music. Depending on how you write and break up your lyrics, you may fit one line or two, however if you write lines the way I showed you earlier with roughly 10­16 syllables, that is meant to fill one bar. Some rappers like to write half­bars and divide lines at the two count, for the sake of simplicity and our purposes, one bar correlates with one line. Exercise: For this exercise I want you to find instrumentals and full rap tracks that you like and try to follow along and count bars as they go. Do the instrumentals first as it will be much easier without someone talking. After you get a good feel for counting bars, I want you to use one of the instrumentals and simply count 1, 2, 3, *word*. So instead of saying the number 4, I want you to use a word, then I want you to count again and use something else to rhyme. So for example: 1, 2, 3, fish 2, 2, 3, dish You can pre­write these rhymes if you want to, but I want you to start getting used to dropping a rhyme on the fourth count as you get started. This is going to help you prepare for freestyling, as well as written verses. The next step in developing this skill is to start replacing the numbers with words as you count. So for example instead of saying: 1, 2, 3, 4 You say: We, go, all, day Obviously this sounds really robotic, but it will start building the foundation for better flow. As you feel more and more comfortable, you can start playing with adding additional words between counts. Again, ultimately this is not a formula you need to follow for rapping well, it’s just a way to start building your skillset. Worksheet: 1. Count bars on an empty instrumental 2. Count bars on an actual song 3. Count bars on an empty instrumental but sub out the numbers for words Supplemental Material: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QWfRzyj6P4s https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JyW1QYzeX40 Day 8: Adopt­a­verse Content: We are going to tone back the hard learning today and focus on an exercise to develop a few skills. This idea was given to me several times as I learned to rap and many others have said it helps them tremendously. To do this exercise, you need to have a song memorized. I hope you started on day 2 working on memorizing a few songs. We are going to emulate, deconstruct and reconstruct these songs and use them as a framework for starting to rap. Once you memorize a song, I want you to study it. Look at the lyric sheet carefully. Pay attention to the way words are placed, the way the artist delivers them, and the way it all comes together. If you listen to each of the aspects enough, you should start to develop a decent understanding of what it takes to create and deliver that song. For this exercise you will essentially create a cover, by reciting someone else’s lines using their flow to start with. Once that feels comfortable, you will keep changing lines as you practice until your lyrics are different. Now remember, in the long run I don’t want you to steal their style, just learn from it and find things that help you. Use these finished songs to feel out how established artists flow and how they develop their lyrics. Notice how many syllables are in their bars and how you could potentially alter them. This is not an exercise for creating an original song, nor is it where I want you to be by the end of the course, but it is a great starting point. Listening to other artists is a great way to develop our own talents and it is much easier to do a cover than to create an entirely new song on your own. Use this to understand the skeleton of the art. This is also a great starting point for getting used to your own voice. Many beginning rappers are nervous about what their voice sounds like, but I’m yet to meet an individual who doesn’t like to belt out verses with their favorite songs. By focusing on songs you like and losing yourself in the music, you lose the criticism of your voice, which is exactly what we want to develop. The less self­conscious you are of your voice, the better, it’s much easier to tap into your confidence this way. Exercise: Find some of the songs you have memorized and get their lyric sheets. Study them carefully, then sing along with those songs. It is especially educational if you pick songs with multiple artists who each have their own verse because they will each flow differently. To start recite the song a few times, exactly as the artist does. After you feel comfortable with that, use their lyric sheet to change a few of the words. End rhymes are a great place to start, so for example if a line says: Throw a fist at the wall if I can’t hold it in You edit it to: Throw a fist at the wall if it is cold again But really you can edit anywhere in the line you’d like: Blow a kiss at the mall, since I can’t hold it in You don’t have to make it rhyme, but I want you to get used to playing with the lyrics. If the syllable counts are the same, you should be able to mimic their flow with your own words. This exercise will teach you how that particular artist flows on that particular song. Eventually, you’ll be able to change every line in the verse and recite it along with the original instrumental, creating your own unique content. Keep doing this with a lot of different songs and I guarantee the idea of flow will take root in your mind. Flow is one of the cornerstones of rap and we want to start developing it as quickly as possible. Worksheet: 1. Pick the song you are going to use 2. Record yourself reciting the song. 3. Record yourself reciting the song with some minor changes. Day 9: Freestyle ­ Anything! Content: Today I want to focus on getting more comfortable with your voice, speaking rhythmically, and starting to freestyle. This is similar to the second day, where you were encouraged to overcome perfectionism by powering through and writing anything, but instead it will be vocal. One of the biggest hurdles to overcome in freestyling self­judgement. You need to get into a mindset where you keep going even if you make mistakes. Freestyling is supposed to be fun, but often people get so caught up in proving something they end up freezing or not even trying. There’s nothing to prove. Just be yourself, express yourself, and get some vocal practice in. When you relax you are going to freestyle better anyway. Before you freestyle take a few minutes to clear out your mind. Take out whatever expectations you have for yourself. Regardless of skill level, there’s value in working on your craft. If you were learning how to play basketball, would you expect yourself to instantly be able to dribble behind your back? No. It takes practice, and just because this medium includes words does not mean it’s different than any other skill. You need to practice, ditch the perfectionism, and set yourself incremental goals for getting better. Before you freestyle you should also listen to a lot of different freestyles. Truly, genuine freestyles. Most professional rappers have pre­written phrases put together if they are going into a public setting to ‘freestyle’. This is not to say there are not genuinely amazing freestylers or legitimate freestyles out there, I just don’t want you comparing yourself to what you hear on tracks labeled as freestyles that aren’t actually spontaneously created. Listening to actual, off­the­top freestyles will build your rhyme vocabulary and see ways other rappers approach freestyling. Exercise: Find 3 instrumentals you are familiar with and rap along with them. Say anything you want. Be confident. Don’t whisper it to yourself, don’t do it in your mind. Actually say words out loud. Don’t worry about the content, don’t worry about if it rhymes, don’t worry about if it’s repetitive, don’t worry if you say made up words, don’t worry if the whole thing is gibberish. Just keep going. Worksheet: 1. Pick 3 of the instrumentals given, or find your own. 2. Record each freestyle then listen to it. Day 10: Overcoming Doubt & Using Feedback Content: Congratulations on making it to the last day of the first section. You have already put in a lot of work, you should be proud of yourself for making it here. I want to take another day to focus on being happy with what you create and avoiding self­judgement. The exercise I’m going to ask you to complete today may make you nervous and you may find it difficult, but it is essential on your road to growth. I’m going to ask you to share some of your work. For some, sharing your work will be one of the most difficult things for you to do. You will be afraid of the comments, afraid it is not good enough, afraid of so many things. Do not let this fear conquer you from sharing your art with the world. As mentioned before, even if you don’t like a particular piece, others may get something out of it. Even if you get terrible, harsh feedback, that feedback does not affect who you are. Not everyone will like everything you do, that’s completely ok. Move on and work on your next project. There’s a few reasons why sharing your work and progress with others is essential. Sharing your work lets you share your talents, it lets you build a fanbase, and most importantly, it allows you receive feedback. Not all feedback is the same though, let’s distinguish between types of feedback you can receive. Good feedback has specific points you can address, for example, “I didn’t really like that last line, it felt like there were too many syllables and you had to rush to make it fit” In this example, you know exactly what the listener did not like, and you know what to work on. That does not mean you have to change it in the future, but you at least know what they were concerned about and can think about how that factor influences your music. This is the type of feedback you are looking for. When you find someone who gives you good feedback, make sure to take note of it and use them as a resource. Mediocre feedback will leave clues as to what they don’t like, but you will have to dig for the actual underlying issue. An example of mediocre feedback is “Your vocals were a little off”. This gives you an idea of what they thought you could work on, but not enough to specifically know the problem. The best thing you can do with mediocre feedback is ask for more information and clarification. Don’t spend hours agonizing over whether they meant your tone was off, or your flow was off, or whatever else it could potentially be. Just ask, if they can’t specify, take note of what you can and move on. Bad feedback looks like this “That was the worst thing I’ve ever heard, you’re garbage”. What can you pull from this feedback? What points can you consider? Nothing. The individual has left you no valid points to revisit, nothing to contemplate. This also applies to feedback like this “Wow! Best thing I’ve ever heard.”. Even though his is positive, there is still nothing valuable you can gain from the comment for improving in the future. Let’s be honest though, that kind of feedback still feels fantastic. I want to emphasize one point; do not let negative feedback get you down. If there are valuable points in the feedback, consider them. If there is nothing of value in the feedback, ignore it. There’s not enough time in life to stress over toxic people who want to insult you and bring you down. Move on, find the ones who do enjoy your work, and keep practicing. Feedback goes both ways. When you are critiquing someone else’s work do them the courtesy of finding specific points you feel they can work on or let them know specific things they have done well. The more specific you are, the more they will be able to get out of it. Alway aim to give good feedback. Other artists also notice and are more reluctant to give feedback to those who only selfishly ask for advice. As with most things in life, the more you give, the more you get in return. Giving feedback will also help you learn and grow as an artist, so there really is no downside. Don’t be lazy. Exercise: Today’s exercise includes a few things. The first is, as we wrap up this section you may have noticed you have certain areas that come more naturally than others. We’ll start by giving yourself feedback through writing a list of your strengths and weaknesses. Write as much as you need to flush out your ideas, but I recommend at least 3 strengths and 3 weaknesses. Then come up with a few ways to work on your weaknesses. Knowing yourself is critical to developing as an artist. You should also create something new and share it with someone, preferably in a recorded or verbal form (we’re not just writers here, I want you to develop your skills in a well rounded way). Anyone, be it a friend, significant other, family member. Anyone. Don’t judge yourself, but do ask for feedback. Be prepared for any kind of feedback and don’t let the result get to your head. Just use any valuable information you get and keep moving forward. Finally, pat yourself on the back. You just finished the first section. Worksheet: 1. What are your 3 strengths and 3 weaknesses? 2. What can you do to improve your weaknesses? 3. Write 8 lines (or whatever you want). 4. Record or perform in front of someone. 5. Write down the feedback you get. Is it useful or not? Supplemental Material: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9NL_OLXMbM Developing Starter Skills Day 11: Finding Concepts Content: Welcome to the second section of the course. Earlier we went over why you want to rap. Now we’re going to shift focus toward what you’re going to rap about. When artist don’t know what to write about, my first suggestion is the set of exercises to overcome writer’s block. But what if you want to write something with more direction? Something more planned, focused. Let’s go over a few ideas for common styles and sources of inspiration for many artists. One of the most prevalent styles in rap music is braggadocio. Braggadocio refers to the style of rap that focuses on boastfulness. These are the verses that talk about making a lot of money, being better than others, etc. This is also the style most similar to battle rap. Braggadocio is a fun style that allows you to let loose, crack jokes at other people’s expense, and talk about how good you are. Key skills in this style; confidence and clever punchlines (we’ll cover those later). Another common source of inspiration is personal experiences, with a focus on emotions. Ideas from this source are things like trouble at work or a new love interest. These verses include problems that you have actually dealt with or thing troubling you. Typically, an audience has an easy time relating to this type of song because it’s rooted in real experiences. These songs are great for catharsis, releasing problems and frustrations you face in your life. Key skills in this style; tone and word choice. Storytelling is also a common theme. Storytelling can easily come up in personal experiences, but you can also make up stories. These could be about anything, from a time you bought ice cream as a kid, to something about demons and monsters, to a drunk driver trying to make it home. This style is fun because it allows you so much flexibility in your topic, you can write about anything you want, really. Key skills in this style; Imagery and creativity. There are lots of other styles you can choose as well such as horrorcore, political, comical, and many others. You don’t have to stick to a specific style and these are not totally exclusive, but sometimes using a theme helps guide song or verse development. You can also pick specific skills you want to focus on, and that may help guide the song as well. As usual, nothing I’ve said today is concrete or mandatory categorization, these are just ways you can break down the craft in your mind to help you focus. Over everything else, your own creativity and the type of art you want to create are what really matters. Don’t get too caught up in definitions. Exercise: First, take a moment and think about what style you typically write in. What concepts do you usually cover? What skills are most important and fun to you? Are you more drawn to braggadocio, or storytelling, how about comedy? It never hurts to develop as much as you possibly can, but there is generally a few styles that will come most naturally to you, and starting there can make it easier to get into the craft. Once you have thought about your style, write 2 separate sets of 8 lines. For each set of 8 lines, pick an entirely different subject or style. These do not have to be styles I mentioned, just get a feel for how different writing focuses changes your mindset, where it takes you and how it feels. This is an exercise to see where you what you are drawn to and gain a better idea of your stylistic preferences. Worksheet: 1. What style comes most naturally to you? 2. Write 8 lines using your most comfortable style. 3. Write another 8 lines in a different style. Day 12: Technical Skill vs. Poetic Spirit Content: Today we’re going to cover something more abstract than many of the other days. We’re going to discuss the idea of technical skill compared to poetic spirit. This lesson is not technical, it’s not anything that I can break down or tell you definitively, and this is exactly the distinction I’m trying to show. There’s a component to rap, a component to art, that cannot be broken down technically. That can’t be given as bits and pieces. I want to clarify; there is no cookie cutter formula or set of ideas that will guarantee you’ll be able to make captivating art. If there were, all artists would simply master the overarching formula, and that would be the end of progression because it would always be beautiful. There is no end. Artists change and develop. Your life changes, your focus changes, your ideas and hopes and dreams all change. Part of what makes art so beautiful is the creativity, a peek into the soul of the individual. Everything that I am able to teach and communicate to you is not a path to becoming a captivating rapper. At least not on its own. You can have all the technical skill in the world, but if you don’t infuse yourself, your life and your style into your work, it will fall flat. All of these skills, rhyming, wordplay, flow, etc. are merely a toolset for tapping into that underlying humanity. Understanding these skills will give you more power to express yourself clearly, but they do not create the poetic spirit. Ultimately, you must learn to tap into this part of yourself. This is why this course has such a heavy emphasis on letting go of judgments and embracing the process. Worrying about what others think, or trying to create work exactly like them, dampens your spirit. You fit yourself into the work of another individual and crush your own individuality. There is a stark difference between learning from other artists and trying to become them. I believe this is why cover songs can be so beautiful, or so painfully awkward. When you try to become an exact copy of another artist, your poetic spirit loses ground. When you let that spirit free, even using another’s work as a sounding board, you get something entirely unique and beautiful in its own way. Another trap which catches many beginners is creating music solely to meet the expectations of others. This is a recipe for failure. When you impose outside forces on yourself, it becomes too easy to lose the beauty of your own art. You lose your originality. I’ve seen this happen all too often with individuals trying to create music in a style that is much more aggressive than they really are. They feel like rap must fit into the braggadocio style that is common, and try to emulate that, even when it is not truly the style of music that meshes with who they are. Don’t fall into that trap, it will save you a lot of time, trust me. Don’t worry, I won’t stray too far into my philosophy on rap. Tomorrow it’s back to the concrete skill building, I just wanted to leave these ideas with you as you think about what this art means to you and where you are drawing from for inspiration and creation. Exercise: Think about what is holding you back from being completely free with your work. What stops you, what inhibits you? Are there outside pressures? Fear? Take time to write down a list of a few things that stop or even slow you down during the creative process. I’m not saying creating work should be instant, but more that there are things that stifle your creativity. What are they? There have certainly been times where I have compromised myself to try and create something specific because of what others expected, and it turned out poorly. Worksheet: 1. What outside pressures do you feel? 2. What holds you back from producing? 3. What can you do to overcome those barriers? Day 13: Internal Rhyming Content: Today we’re going to focus on internal rhyming. Internal rhyming is a pretty simple concept to grasp, but much more difficult to execute effectively. Internal rhyming is the natural next step after end rhymes to build more complex rhyme schemes. So what are internal rhymes? Internal rhymes are simply adding extra rhymes within the lines in addition to the end rhymes. For example: I went (deep) into a heavy (sleep) Thinking of things that made me (weep) Again, not particularly difficult to understand. The skill to work on and develop here is using internal rhymes in a way that does not derail the verse you’re writing. Sometimes people get so caught up in rhyming, they lose track of the meaning they want to give the piece. Sometimes artists purposely rhyme in a way that doesn’t make sense to create a certain type of sound, but I want you to be aware of the difference and mindful of how you are using rhymes. Don’t allow them to overpower your verse, use them to enhance the style you are trying to exhibit. There are a few strategies you can use to add internal rhymes into your lines. One of the easiest ways is to use our earlier strategy of creating a rhyme list. Once you have a list of rhymes you can use those words to map out your verse and put the words together. For example lets take the word fire and create a rhyme list. Fire, tire, liar, pyre, choir, hire, higher, friar, spire, etc. We then select the words we want to use together: Friar, choir, liar, higher, retire Once you have a list, you can use those words to build lines with internal rhymes: The (friar) in the (choir) was an awful (liar) Said he couldn’t sing (higher) so he had to (retire) Again, the trick is not placing the rhyming words into the lines, the trick is to be able to add these rhyming words and still get the effect or meaning that you are looking for in the verse. Look for related words, or at least ways to relate words. People can tell when you force rhymes, as the language sounds awkward or the topics don’t quite mesh together. Internal rhyme does not have to relate to the end rhyme in the line. You can also have internal rhyme using other schemes besides AA,AA. As long as the rhymes are within the line, it all counts as internal rhymes. For example: The (weak) people (seek) a new strong **hero** The (meek) don’t believe in anything but a **zero** Even though the end rhymes don’t match the other rhymes, they are still considered internal rhymes. Internal rhymes also do not have to stick to the couplet format. For example: The (weak) people (seek) a new strong **hero** The (meek) don’t believe in anything but a **zero** It’s (bleak) when you don’t dare place your *faith* Fear (reeks) of deceit and lies make a *maze* In this example, the internal rhymes continue for 4 lines, while the end rhymes change. As you can see, there are a multitude of potential rhyme combinations to create new and unique rhyme schemes. Playing around with internal rhymes is a great way to add more rhymes to your verse and give it the extra pop it needs lyrically. Exercise: For today’s exercise you’re going to write 8 lines that all have internal rhymes of some sort. For the first 4 lines, I use internal rhymes that relate to the end rhyme. For the second 4 create internal rhymes that don’t relate to the end rhyme. If it helps you and you need it, make a list of rhyming words beforehand so you have rhymes ready when you construct the lines. Try to create something that both rhymes and has coherent content. Worksheet: 1. Create a list of rhyming words for 2 different words 2. Write 4 internal rhymes that relate to the end rhyme, label them. 3. Write 4 internal rhymes that don’t relate to the end rhyme, label them. 4. Identify the internal rhymes in the following lines: Got to write lines that bend spines by force of thought My will sends men to their knees right on the spot Power of the pen is ten times when within my grip Devour words each hour until my insides rip Answer Key: Got (B) to write lines(A) that bend spines(A) by force of thought (B) My will sends men (c ) to their knees right on the spot (B) Power (E) of the pen (c ) is ten (c ) times when within my grip (D) Devour (E) words each hour (E) until my insides rip (D) Day 14: Slant Rhyming Content: Today we’re covering an extremely important skill, slant rhyming. If you only use perfect rhymes your range of expression is highly limited. Some words have few perfect rhymes and others have none at all, which are difficult to use without the rhymes sounding forced. That’s why we use slant rhymes to fill the gaps. Once you get a strong understanding of slant rhymes, you will have almost unlimited ability to add rhyme sounds into your verse, while still being able to get your message across. If you remember, perfect rhymes are when the last syllable in the word have the same ending sounds but the starting sound is different. For example (h)og and (d)og. Slant rhymes are when the two words have similar consonant or vowel sounds, but may not necessarily be arranged in the same way as a perfect rhyme. Let me give you some examples: Plate/Grape Throttle/Fatter Flag/Flat You may be looking at these word pairs wondering what makes them slant rhymes, so let me break down each one a little more. There are two components to creating slant rhymes, assonance and consonance. This happens when there is either vowel sounds or consonant sounds that are the same between words. In plate/grape, both of these words have the same vowel sound. Pl(AY)te/Gr(AY)pe. While the other letters and sounds are different, these vowel sounds are the same. When vowel sounds stay the same while other sounds change between words, this is called assonance. We could also add flake, wait, and played as assonance rhymes to these words. (Fl(AY)ke, W(AY)t, and Pl(AY)ed) Finally let’s take a look at Thro­(TT)le/Fa­(TT)er, here, the repeated sounds fall on a consonant. When this type of sound is repeated anywhere within words it is called consonance. Typically, consonance sounds more slanted than assonance because the ear most easily notices similar vowel sounds and relates them to rhymes. We could also add pra(TT)le, ba(TT)ed, and a(TT)ack to this list. This is a special kind of rhyming called alliteration. Notice configuration similarities between (FL)ag and (FL)at, here the first sounds are the same and the end sounds are different. As you may have noticed, alliteration is a subset type of assonance or consonance, just at the beginning of the words. We could also add (FL)ap, (FL)ask, (FL)are, and (FL)ame to this list and they would all fit this category. Using these different tools allows you to play with the sound of language and really expand your rhyme flexibility. Typically, the more sounds two words have in common the closer it is to a perfect rhyme, and as fewer sounds are repeated the rhymes becomes more slanted. Again, there are no rules here, these are simply ways to identify and think about the types of rhyme you are using within your verse and how you can potentially use them to create the sound you want. Let me show you an example of a verse with slant rhyming: Listen, I’m on a mission to spit precision Diss and ditch the division of little livin’ Cause my vision shows me giving the prison A revision of life in spite of the bitchin’ Here is it broken down: L(I)st(en), I’m on a m(i)(sh)(en), to sp(i)t prec(i)(sh)(en) D(i)ss and d(i)tch the div(i)(sh)(en) of l(i)ttle l(i)v(en) Cause my v(i)(sh)(en) shows me g(i)v(en) the pr(i)s(en) A rev(i)(sh)(en) of l(EYE)fe in sp(EYE)te of the b(i)tch(en) Throughout this verse you can see a mix of perfect and slant rhymes, mainly using assonance. Mastering the use of slant rhymes is what makes a verse sound elegant while maintaining the intent the author is trying to show. At first, it can be very difficult to identify what is “too slanted” and what sounds nice, but as you practice things will be become more clear. One helpful strategy is to actually recite the lines aloud. This is actually helpful with any type of writing as once you hear it verbalized you can often pick out mistakes and strong points. Remember, just because the letters are the same does not mean they make the same sound. Take aim/all for example. There is weaker assonance here because the sounds are different (Ayy)im vs (ah)ll. The sounds are what is important, not the letters, which is another reason why pronouncing the words aloud is helpful. Exercise: Today’s exercise is broken into two parts. For the first part, pick 3 words and come up with at least 5 slant rhymes for each word. You also need to break down why each word is a slant rhyme by identifying what sounds are being repeated. You can break it up as I have done above, or you can put together your own style if it is easier for you. For the second half of the exercise I want you to write 8 lines and then break down where you have included rhymes, both perfect and slant rhymes. Again, you can use the style I’ve provided, or you can break them down in whatever format you most prefer. Worksheet: 1. Word 1 Slant rhymes & breakdown 2. Word 2 Slant rhymes & breakdown 3. Word 3 Slant rhymes & breakdown 4. Write 8 lines, identify slant rhymes More Examples: Love/Thug/Run ­ (uh), Assonance Trap/Train/Trust ­ (tr), Alliteration Flush/Bust/Cussed ­ (uh), Assonance Will/Ball/Full ­ (ll), Consonance Moss/Glass/Fuss ­ (ss), Consonance Lap/Flip/Carp ­ (p), Consnance Start/Stamp/Steal ­ (st), Alliteration Part/Shard/Car ­ (ar), Assonance Break/Brand/Breath ­ (br), Alliteration Supplemental Material: Slant Rhymes pt. 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JJw­XMnBQaQ Slant Rhymes pt. 2 (Consonant Letter Groups): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nqqpnCiTVkI Assonance, Consonance, Alliteration: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OVMjxenOKmg Day 15: Vocabulary, Word Choice & Imagery Content: Today we’re going to cover vocabulary, word choice, and imagery. Each of these subjects are related and contribute to the way you communicate ideas. These are the difference between having a bland, generic verse, and having powerful language that listeners are drawn to. The set of words that you know and understand is called your vocabulary. Having more words at your disposal increases your ability to communicate as well as your options for rhyming. It is no surprise many rappers spend time studying the dictionary to increase their vocabulary. Personally, I’m not interested in that, there are other ways you can increase your vocabulary. The easiest is reading regularly and looking up the definition of any unknown words. If you’re not much of a reader, you can always watch shows or listen to podcasts with complex content. At the very least, you should look up unknown words you hear during conversations. The stronger your vocabulary is the better. How you use your vocabulary is also important and that is word choice. You might know a ton of words, but if you don’t scrutinize your word choice, it doesn’t make you a better communicator. Picking your words wisely enhances your content, and gives the listener clarity on your subject. The more specific you are, the more clear your intent is. Let’s compare examples: The dog was fast. vs. The doberman was fast. or The house was big vs. The house was enormous In both examples, the more specific word creates a more specific image. By being specific instead of vague and generic, you control the emotions and ideas being communicated. Now there are circumstances when you would want to use a more generic language. Wordplay is a great example, as you want to be ambiguous to create multiple meanings. In those circumstances your word choice is even more important to make sure the plays make sense. It also helps to keep your mind open for descriptive alternatives so you can maintain flexibility with your rhymes. Another aspect of word choice is making sure you aren’t using unnecessary words. Some rappers describe a scene using filler instead of concise, powerful language. This may not be a problem in all circumstances, but it can become difficult to flow when you cram too many words into a line. That may sound contradictory to the rest of the discussion, but length is something to be mindful of when you are writing poetically, because syllable counts are important. Know that you can likely cut words to reach the same effect. For example: I remember it seemed like a really long time ago vs. It seems like long ago Both communicate the same idea, but the first version is much longer. You can still expand on ideas, but if you need to conserve space to fit a particular line count or preserve flow, identify which words are impactful and cut the rest. Language is flexible, there are always options. Word choice is essential for communicating the ideas you want, paying attention keeps you in control. A sub­skill of word choice is Imagery. Imagery is the skill of using words to create strong sense­based experiences. Words that evoke images, smells, tastes, feelings or sounds help others imagine the exact experience you’re speaking about. Imagery is most important in storytelling, but is still important regardless of what you rap about. When telling a story, you need to describe the scene. Again, the more specific you are, the stronger impression it leaves on the listener. Using imagery and appealing to the senses quickly develops your scene in a powerful way. Here’s an example: I tripped and fell, nose had to take the fall Blood ran down my face, did I break it all? vs. Tripped, heard a loud crack, nose had to take the fall Blood dripped down my face with the taste of salt Which of these lights up your senses? Which experience can you relate to more? Imagery is a strategy for creating more powerful scenes. As you can see, rap is highly interwoven with poetry, many of the same techniques can be applied with great success. As you move forward, pay attention to the way you communicate ideas. Exercise: For today’s exercise select five words or phrases you commonly use and either think of or look up 3 alternatives to each. This exercise will help expand the number of options for explaining situations. There are so many options for expressing something, the more you have at your disposal, the more you can play with the language. Make sure you fully understand the alternatives so you can use them appropriately. For the second part of the exercise write 8 lines focused on imagery. Think about the sensory experience in a scene and do your best to describe it, while still using the things we have learned previously. This exercise will help you get accustomed to writing with sensory experience in mind. If storytelling is one of your priorities, strong imagery is a cornerstone. Worksheet: 1. Select 5 words or phrases 2. Find 3 alternatives for each word or phrase 3. Write 8 lines, focus on imagery Day 16: Delivery ­ Tone, Confidence, Memorize Content: The next thing we’re going to cover is delivery. For the purpose of this course, delivery is the culmination of everything you do vocally when reciting lines. This includes tone, flow, and breath control. While perfecting your delivery is certainly difficult, there are a few easy ways to overcome the most common issues. We’ll be going over a few strategies for building those skills and tomorrow we’ll go over some more. One aspect is your tone. Tone is essentially the way you recite your lines and it stems from emotions. Delivering your lines without emotion, or with a confusing emotion, makes it difficult for the listener to relate with the music. It is similar to how an actor must create a believable character to fill a role. The biggest tone problem I see is new rappers reading verses without any emotion. They almost seem bored with themselves. How can you expect listeners to be drawn in if you don’t respect your own art enough to give it the energy it deserves? You must have energy and emotion if you want people to pay attention. Take time to record when you are feeling the emotion that corresponds with your verse. If it’s an angry verse, record it when you’re angry. Draw from the experiences that produced the writing to produce the tone. If you can’t recreate the emotions in a genuine way, start acting. Find a routine that changes your emotional state. Listen to other songs that share the same vibes you’re looking for and get lost in them. Imagine situations until you start feeling the right emotion. Pretend you’re in theater and putting on a performance. It doesn’t matter how you do it, as long as you tap into the right emotional base. People can tell when you don’t have the emotion to match your lyrics and they disengage. Do not be monotone or mechanical, find a way to let yourself bleed into the music. Confidence is another aspect of delivery. I know we hit on confidence fairly regularly, but it is absolutely essential. When you are not confident in your delivery people notice. Some may see this weakness and support you, but others will see it as a point to attack, which will only further impact your confidence. When you recite lines, I want you to operate under the mindset that everyone wants to hear them, regardless of if it is true or not. Assume you are dropping a great verse and you’ll be surprised how often it works. If we have to talk about extremes, it will be more engaging for listeners if you’re cocky instead of timid. If you get nervous, try closing your eyes for a few minutes and breathing deeply before you perform. Long, deep breaths will automatically put your body in a more relaxed position and calm your nerves. The goal is to stop worrying about what others think and lose yourself the music. Easier said than done, I know, but once you find this zone everything feels more natural. People are more likely to be impressed and you are more likely to feel happy with your performance. Memorizing your lines is another thing you can do to instantly improve your delivery. When you don’t have your lines memorized you have to read them. Most people use a different voice for reading than they do when speaking naturally. The voice is typically more flat, boring and lacks emotion. This happens because when you read a verse, part of your attention is dedicated to reading the words on the page and recreating them aloud. When you have the lines memorized, you can recall them from memory and focus on perfecting your tone, breath, and flow. This doesn’t mean you can’t deliver a good verse while reading, it’s just more difficult. Memorizing the verse will let you focus on the delivery. These are just a few basics you can use to improve your delivery. Tomorrow we will go over a few more basics. As mentioned, flow is a huge component of delivery. Later we will spend quite a bit of time on how to develop and improve flow. For now, I want you to focus mostly on your emotional energy and confidence. These are absolutely essential. Exercise: Write 8 new lines and recite and record them, with or without music, whichever you feel most comfortable with. Practice this delivery several times. Play with the ways that you can deliver the lines. Try different moods such as happy, sad, angry. Regardless of what emotion you decide, fully invest in it. Do not hold anything back, let the words flow through you as naturally as possible. Write another 8 lines and record yourself reciting them. After that, memorize the lines. Make sure you can read the entire set without looking at a paper to help you. Then deliver them again and record it. When you listen to the memorized recording, the lines are almost definitely going to sound more natural as you can focus on delivery instead of reading. Worksheet: 1. Write 8 lines. 2. Record them with emotion and confidence 3. Write 8 more lines 4. Record them before and after memorizing them Supplemental Material: Emotion: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2balfGOQ­Sk Memorize: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vyBxYn7ec4Y Day 17: Delivery ­ Breath Control & Pronunciation Content: Today we’re covering a few more drills for improving delivery, this time breath control and pronunciation. These may seem small but each component plays into your overall delivery. With each part you practice, the more you will improve. Let’s start with breath control. Breath control has to do with how many syllables you can say before you need to take another breath. Having great breath control allows you to breathe at appropriate times and create faster flows. Running out of breath will make it impossible to recite your verses or force you to gasp for air during your recordings. You will most certainly hear that on the playback. There’s a few ways to work on your breath control. One is to practice faster flow, this can be done by putting more syllables into your lines and bars. You may find yourself running out of breath quickly, but keep pushing through and, with practice, your body will eventually adapt. Another thing you can do is work on your physical fitness, namely your cardio endurance. Let this be another motivation to get in the gym. A great way to improve your breath control quickly is to actually rap while you jog or walk. This is going to push you but it’s worth it. And before you yell at me about all the fat rappers, I know. This is just one way you can work on breath control, clearly not the one they chose. If you are struggling with breath control in your songs try to write less syllables per line, or actively set pauses in your verse until your breath control improves. Don’t get frustrated if it takes some time. Progress and process are always the goals. You can also record a few lines at a time, instead of an entire verse, and clip them together. This may not sound as natural, but it will be much easier if you’re struggling with getting enough air. Pronunciation also plays into your delivery. Pronunciation is how clearly your syllables are spoken. Some rappers intentionally slur their speech, but most are trying to be understood. You spend a lot of time on your lyrics, you probably want them to be heard. If you don’t care about your lyrics, you can skip about half of this course. One way to work on clearer pronunciation is to exaggerate the motions of your mouth when you speak. By moving your mouth in a highly animated way, your syllables will automatically come out more clearly. Performing this exercise looks ridiculous, but it really does help. As you practice more, you’ll be able to maintain the pronunciation while moving your mouth in a normal way. You can also put a pen in across your mouth and try to speak clearly. This looks even more ridiculous than the last exercise, but is extremely effective. You have to work twice as hard to create the sounds you need, can’t cheat, and once you take the object out of your mouth it’s very easy to speak clearly. The best way to find a delivery you are happy with is to practice and experiment. If one of the components interests you, take time to find other exercises to work on that skill. Ultimately, the goal is to find a style that makes you comfortable with your delivery. Exercise: First, to work on your breath control try freestyling while you walk or jog, depending on what you can handle. Exercise primes your mind, so you may find it easier to freestyle. On the flip side, exercise is taxing on the body, so your mind may be more stressed and less likely to come up with ideas. Either way, freestyling while exercising is a drill that develops multiple skills at once. Second, to work on clearer pronunciation write 8 lines and then recite them. The first time, recite the lines as you normally would. Then recite the words one more time, intentionally slurring and making them sound sloppy. The last time, slow down and make sure you say each word clearly. This will help you understand your current range of pronunciation. Worksheet: 1. Freestyle while exercising. 2. Write 8 lines. 3. Recite them normally. 4. Recite them intentionally sloppy. 5. Recite them extra slowly and clearly. Supplemental Material: Clearer Pronunciation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e5tXyW9Kw7o Day 18: Song Fundamentals Content: Today I’m going to outline the basic steps to making a rap song. First, let’s talk about the structure of a song. Rap songs are composed of verses and choruses (also called a hook), as well as an intro, outro, and sometimes a bridge. The most general outline for a rap song is 3 verses and 2­3 chorus loops. The verses are generally 16 bars with the chorus being 8 bars, and typically the intro and outro are at least 8 bars. A general song outline looks like this, intro, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, verse, outro. Actual songs have all kinds of different compositions, however, verses are typically filled in multiples of 8 bars. There are songs with no chorus, songs with 5 verses, songs with 1 verse, it really depends on the instrumental and how the rapper and producer work together. If you listen carefully to an instrumental you should be able to pick out the structure of the song based on when musical changes occur. These changes usually line up with the bar guidelines given above, but not always. As for content, verses are typically more complex, focused on lyrics, less repetitive, and contain most of the content in a song. Choruses are typically more musical, and are often sung, but can be rapped as well. Choruses tend to be shorter than verses, are repetitive throughout the song, and are more simple. Bridges are places where the music changes abruptly within the song, then goes back later. Think of a bridge as a musical break within the song, a change in what your ear has grown accustomed to. The intro and outro pieces can be left as blank instrumentals, rapped over, sung over, talked over, or overlaid with dubs. It really depends on what the artist wants to accomplish. This can all sound confusing, but it just means there’s a lot of flexibility in how songs can be composed just look for patterns and changes. Now that we’ve covered song structure, let’s discuss writing a song. One important consideration before you start writing is the structure of the instrumental you’re using. How many verses do you have to work with? Is there an outro? What about a bridge? All of these spaces in a track can be used, whether or not you use them is up to you. Some people are less technical, don’t plan, and like to see where the song takes them, but identifying how much space you have to work with really illuminates your options. Listen to the instrumental until you are able to break up the song mentally. That will make it much easier to tie your song together as you write. There’s a few strategies for starting a song, which are all pretty self explanatory. You can start with a theme for verses, start with a chorus, or pick an instrumental. What it really boils down to is picking something and being creative, but I’ll delve into each strategy a little more. Starting with a theme means picking an idea you want to work with, finding an instrumental that fits that theme, then writing. This strategy works best if there is a particular topic you want to address. For this strategy you pick the instrumental, then write the verses so you can stick to your theme. At the end then you come back and think of a chorus to ties the verses and the instrumental together. Many rappers like to start songs by writing a chorus first. Here you either find an instrumental with a chorus, or start by writing a chorus. You then use the chorus to guide the content and fill the verses. This can be useful if you like having a few central ideas to come back to for your verses. Finally, you can start by picking an instrumental and seeing where it takes you. By listening to the music and letting it guide you, it is easier to match your written tone more naturally to the music. Here, you write whatever comes to you. There is no best strategy to use, it just depends on your goals and what works best for you. Exercise: For today’s exercise listen to an established songs and break down how it is structured. Define its organization by chorus, verse, intro, outro, etc. Then listen to the instrumentals for that song and think about where you can place your own lyrics. Find a few other instrumentals to break down and practice on. When you’re feeling comfortable, find an instrumental and start on your own song. Have one finished by the end of section 2 for practice. I know writing a song can take more than one day, so the exercises in the next few days will be a bit easier. Don’t worry about how it turns out, you have to start somewhere. Worksheet: 1. Pick a song and explain its organization 2. Use the instrumental to that song as practice 3. Start writing your own song Supplemental Material: How To Start a Song ­ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JIR8qY6CwOE Day 19: Freestyle ­ Rhyme Base & Backup Phrases Content: Today we’re going to focus on ideas for freestyling better, as this is a skill most rappers want to develop. Earlier, we covered how important it is to keep freestyling no matter what you’re saying or how far off you are. Today, we’re going to focus on building your rhyme base and creating backup phrases. To freestyle you need to build up a good base of rhymes your mind can pull from. Two of the best ways to do this are practice and writing. Practice should make sense, but how does writing help? Writing with a consistent rhyme scheme helps you freestyle because it grows the connections in your brain between rhyming words. The more you write, the more readily those words come to mind when you need them. There are also a few mindset strategies you can use to improve your freestyle process. First, use common, simple, single syllable words if you’re having trouble thinking. You don’t need a wild vocabulary for a freestyle to sound good, especially when you’re starting out. It may feel like you are being too basic, but it often sounds better than you think. Trying to be too complex can really trip you up, your brain will freeze and the words stop coming, which kills a freestyle. Another strategy many rappers use is a backup phrase. This is a phrase you use if you don’t know what to say next and need more time to think. If you listen to an individual freestyle for a while, you’ll likely hear a few phrases that they repeat. For me, this phrase is “And if you don’t know…..” I also use, “I don’t care if”, or “I said that….”. Having some of your own phrases will ensure you always have something to start or fill a line with which can be crucial. Exercise: For the first half of today’s exercise write 2 sets of 8 lines, using the same rhyme word for each set. This will help build those rhymes into your brain for future freestyles. For the second half of today’s exercise freestyle without a beat, but make sure the word at the end of each line rhymes. Freestyling without a beat ensures you have plenty of time to think of a rhyming word. Pick a list of 5 words (2 of them being the words you used in the first half), then freestyle as many rhyming lines as you can for each word. Once you run out of rhymes for a word, move on to the next one. Don’t take a ton of time to think them up, just say the first thing that comes to mind. Say the words out loud and with conviction. Practicing how you would perform is ideal. It trains your brain to always put forth a full effort. Remember, don’t judge yourself. Just let loose. Worksheet: 1. Write 8 lines, rhyme set A. 2. Write 8 lines, rhyme set B. 3. Make a list of 5 words. 4. Freestyle with those words until you’re out of rhymes. Day 20: Freestyle ­ Cyphers & Surroundings Content: Today we’re still working on freestyling with another idea and exercise. One common freestyle problem is running out of ideas. Rappers end up saying the same things over and over again and can’t change the topic. It can be really frustrating when you use the same ideas all the time. We’re going to learn how to overcome that. One easy way is to join or create a cypher. A cypher is a group of people taking turns rapping a few lines at a time. Coming up with ideas is easier because everyone in a cypher feeds off each other. You have time to think of more lines when it’s not your turn and expand on previous ideas. Unlike when you are alone, there are outside inputs to keep your mind on fresh topics. Another strategy for coming up with fresh freestyle ideas is to draw on your surroundings. Mention events that are happening, objects you see, people you know. By looking around and commenting on concepts right in front of you, it becomes much easier to create new freestyles. For example the guy in front of you has on old shoes as a car drives by, you might say: Hey look at that guy with the old kicks Laying it all out there for us, there’s no tricks Look at that car, was that a chevy or ford? I swear the guy inside of it has met me before Unless you’re in an insane asylum, there’s always objects around you can draw from to you to keep you going. You might feel like it’s a cheap trick or boring, but anyone listening will be impressed by the way you incorporate nearby objects and events. It also shows you’re truly freestyling, not using a pre­written verse you’re pretending is a freestyle. Another game you can try is to have someone actively feed you words as you freestyle. This will ensure fresh concepts, but is definitely more difficult than drawing on your surroundings because you are forced rhyme with a specific word. Though it is harder, this game will help immensely in developing your freestyle skills by putting you on the spot and pushing you to think of new rhymes and connections. Personally it’s one of my favorite exercises because, similar to the last idea, people know it’s a genuine freestyle and are usually pretty impressed. While doing this exercise, make sure to go back and learn more rhymes for any words you struggle with. That way you won’t get caught off guard next time. Exercise: For today’s exercise try two different things. One, I want you to freestyle by looking at the objects around you. You can break this up however you’d like, but do it for a total of three minutes. Also, unless you feel comfortable, still don’t use a beat yet. Take a little more time as you need it and make sure the lines come together the way you want them to. Just be mindful of how long you take, it is still supposed to be freestyle. For the second exercise freestyle with someone else and have them give you words or join you in cyphering. Honestly, this is the most fun way to practice. It allows both of you to develop, learn from each other, and showcase your skills. Cyphering with a friend can also be cathartic as it’s a great outlet for any emotions you may be feeling. It can also make for a lot of laughs, as many of the lines come out absurd and hilarious while you try to think quickly. Freestyling is meant to be fun and flexible. Don’t get too caught up in perfectionism. Just keep going and enjoy yourself. Also, if you’ve completed a song from the earlier exercise now would be a great time to share it. Get feedback and start finding areas you can work on. Congratulations on making it through another section! You should have a decent grasp on the basics and know what to work on. Write down a few things you’ve learned and how you think you’ve developed since the first day. Before moving on, catch up on anything you’ve found difficult. The last section has some pretty heavy ideas in it and they all build on previous material. Worksheet: 1. Freestyle for 3 minutes, using your surroundings 2. Freestyle while someone gives you words, or cypher 3. Share your song from the song fundamentals exercise 4. Write down how you’ve developed and your struggle points More Advanced Skills Day 21: Figurative vs. Literal Language (Similes & Metaphors) Content: Welcome to the third section. Before we get deeply into this section, you must realize the concepts in this section are more difficult than the previous two. There’s nothing wrong with taking more time to go over the lessons. It’s more important to make sure you understand how the concepts work than to keep the schedule. I will provide more examples in this section so you have more to work with. The material today focuses on the difference between figurative and literal language and a few ways to use figurative language. Let’s first define the terms, literal language is where you mean exactly what you say. For example, I walked to the store. In this circumstance you mean exactly what you said, that you walked to the store. Then there is figurative language. Figurative language comes in many forms, but the key difference is that you use words and ideas to represent or compare other ideas. For example: When she gets mad she turns into a witch. It is unlikely she literally transforms into a witch, but instead you are using the idea of a witch to describe the woman’s behavior. Drawing comparisons between different words and ideas opens an enormous range of possibility. Using figurative language, you have the ability to describe almost anything. Let’s break down figurative language a little further. There are many forms of figurative language including metaphors, similes, personification, hyperbole, symbolism, and more. All of them involve the interaction of ideas to create representations beyond the literal meaning. Mastering figurative language lets you add a new level of poetic depth to your pieces. Similes and metaphors are the tools that will be described in this course for creating figurative language, though it’s certainly helpful to be familiar with more types. We’ll start with similes. Similes are comparisons of two things using words such as like, than or as. For example: He is as tall as a house She is as big as a truck As you can see, you use one object like a person, then compare the person’s attribute, height, to another object, a house. You can also do this with ideas such as “Justice was like a light, shining brightly”. All you really do is compare two objects. Metaphors are similar but use one object representing another to make a comparison instead. Metaphors create a more direct comparison than a simile. For example: She was a monster last night. This is figurative language of course, because she was not literally a monster. What is intended is that she acted like a monster, but compared more directly. Metaphors are sometimes extended longer than smilies and draw even more comparisons. For example: She was a monster last night. She kept snarling at me. When she got really upset, she let out a banshee scream that echoed throughout the house, draping the walls in a sheet of frustration. There cannot be a literal sheet of frustration, that’s not a tangible object. But as a comparison of ideas, this thing can exist. When you use your imagination creatively, you can understand what is meant by this phrase. This is how figurative language works. Similes and metaphors are often combined with wordplay to make even more complex lines. We will discuss this more in depth when we get to the day for wordplay. You can create you own similes and metaphors by thinking about two separate objects or ideas and thinking of ways they are similar or can be compared. For example, if I start with hat and pencil, these objects may seem completely dissimilar. However, you can use figurative language to draw them together. What do you do with a pencil? Hold it. Can you hold a hat? Sure. Ok then what about something like this: The man gently held the hat in his hand like a pencil Then placed it so it traced his head like a stencil These two separate ideas, seemingly completely different, are easily brought together with the use of figurative language. Are you starting to see the vast number of possibilities? You should. However, this is a more advanced skill, so don’t be discouraged if you find this difficult. One other consideration is to be aware of what comparisons you are drawing. For example: She was as tall as popcorn This may confuse a lot of listeners because relating the height of a woman to the height of popcorn doesn’t create a normal image. She may be really short, but it’s hard for your mind to connect her height with popcorn. I’m not saying any kind of figurative language is better or worse, it’s just important to think about what ideas you are communicating. Some of the most creative and profound pieces of figurative language come from drawing together ideas that are hard to connect. Extra Examples: She was my flower, my love the water and sun She wilted when I left and was offering none I’m a beast in the street, so when you hear me roar The rodents scurry home and come to fear me more Doing laps, body heating up about as quick as tinder Swear I was running faster than Olympic sprinters She was cold as an ice cube to this nice dude Threw her arms up, like she wants to fight you Exercise: For this exercise come up with 4 literal lines, after that 4 lines that include similes or other figurative language. The literal lines should come quite easily, but if you are struggling with the figurative lines, try writing down a list of objects or ideas. You can then pick two of them and look for a way to compare them, even if the comparison is strange. That will get your mind prepared to look for connections between ideas. When you are done with come up with a metaphor that is extended a few lines so you can draw several comparisons on the same subject. If you need a little extra focus, pick one object or event, then try to compare that to several different things. This is a very advanced skill so don’t get discouraged if you find this difficult. Just try, you have to start somewhere. Worksheet: 1. Write 4 literal lines 2. Write 4 figurative lines 3. Write an extended metaphor Day 22: Wordplay Content: Today we’re going to focus on wordplay. Wordplay is another huge concept to fully understand and integrate into your skillset. It also uses figurative language as a basis. At the core, wordplay is using language in a way that emphasizes ambiguity in meaning to draw out clever ideas. It’s a pretty broad definition, with a lot of specific techniques you can use. For this course, the type of wordplay we are going to cover is what I will call ‘double meaning’ wordplay, for simplicity sake. Double meaning wordplay is when you use a word or phrase that can be interpreted in more than one way. Let me give you an example: Take a shot ‘Take a shot’ could refer to either A) Shooting a gun or B) Taking a shot of liquor For wordplay you could use the phrase in the following way: Talking how he blasts guns this dude fakes a lot Even turning twenty one he wouldn’t take a shot Notice there’s a play on both potential meanings of this phrase, in the first line it’s that if he shoots guns it’s fake, and in the second line it’s that even on his 21st birthday (legal drinking age in the US) he wouldn’t take a shot, as a reference to drinking alcohol. This is how double meaning wordplay works, you must integrate both meanings into your lines and draw them together. Listening to other people’s wordplay will really help prime your mind to create your own. The more you listen to others use wordplay, the more naturally your mind finds connections between words and definitions. Battle rap is a great place to hear a lot of wordplay, many of the punchlines contain some form of it. Jokes or comedy also use wordplay fairly commonly, if that’s something you enjoy. Building your vocabulary also helps, the more words you know, the more likely you’ll be able to draw on uncommon definitions to use for wordplay. Another tool you can use to help you think of wordplays is to start with idioms. Idioms are phrases that have multiple meanings, for example: A penny for your thoughts Ball is in your court Cut corners Idioms already have extra meaning built into them. This makes it easy to use them as a baseline for creating a wordplay line. Many of these wordplays are pretty common, so you will want to learn other wordplay strategies as your skills grow and develop. It is important to make sure your wordplay is comprehensible. Sometimes people find phrases or relations that work in two ways but do not take the time to draw the different concepts together in a meaningful way. Simply mentioning a word with two meanings does not necessarily make for a strong wordplay, you have to be delicate about how you integrate the meanings. Let me show you how easily others can misunderstand or miss a wordplay attempt. If you say something like: It’s like I raised a garden cause I got 24 carrots What does that mean to you? Did you notice the connection being drawn? Perhaps you got that it was a reference to gold, but it was really vague and could have easily been missed or confused. How about if I say it like this: My gold jewelry be like gardens that got 24 carrots. Notice how in the first line, you could still be making a reference to gold karats, but without a clear set up, people could easily miss or misinterpret your double meaning. With more context, the reference is drawn more clearly. Make sure you pay attention to how clearly you set up wordplays. There’s nothing more frustrating then spending a lot of time on a wordplay no one even notices. Again, I want to emphasize wordplay is a more difficult skill. Do not be discouraged if you have a difficult time with it. Keep practicing. If you’re unsure, ask others if they understand it. Remember to be creative and focus on the process over the product. Extra Examples: He like them girls with D cups, checks and measures breasts Dude’s like a pirate cause he calls them treasure chests Walked up to ask for the number of a thick mistress Turns out the middle finger is the only way she gives digits Now he’s falling, got hit so hard that fight was damn wild Hit the concrete, watched his neck snap back like the hat style Every bar been laced with skill and inspired by charm All the heat I spit is likely to set off the fire alarm Exercise: Today’s exercise is both simple and difficult, write 8 lines utilizing at least 4 wordplays. Before you get into those lines, it may be helpful to write down 5 phrases or words that have double meanings. That way, you can draw from those phrases to create your lines. Also, be mindful of how you are communicating your wordplay, you want to make sure it’s something people can understand. The more surrounding references you provide, the more clear the wordplay will become. Worksheet: 1. Write 5 words or phrases with double meanings 2. Write 8 lines, include 4 wordplays Supplemental Material: Wordplay (Double Meaning): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=­Ns02AJpK3M Wordplay (Fission/Fusion): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fr­rWnBg­do Day 23: Multi­Syllable Rhyming Content: Today we’ll cover a more complex form of rhyming called multi­syllable rhymes. Many well established rappers use multi­syllable rhymes as they quickly develop advanced rhymes schemes. Holding a certain set of mulis while maintaining coherency is an especially impressive skill. Let me start by explaining what a multi­syllable rhyme is. Multi­syllable rhymes are when sets of words rhyme as matched by their syllable count. To further explain, we will start with a set of words and create a multi­syllable rhyme. For example: Polar Bear Broken into syllables is Po­lar­bear (3) Now for a multi­syllable rhyme, the second phrase must rhyme in the same places as the original phrase. So for this we want to rhyme with both polar and bear, in the same order. Po­lar­bear (3) So­lar­flare (3) This is a multi­syllable rhyme. See how the rhymes add up in the same order? Po/So, Lar/Lar, Bear/Flare. Now let me show you an example of something that would not be a multi. Po­lar­bear (3) Creak­y­chair (3) Here, you are only rhyming one syllable, bear/chair. Or another example of a non multi is: Where­is­this? (3) Chair­lift (2) This is not a multi because the rhymes do not match up on the same syllable counts. Here, the first syllable, chair/where matches but the phrases become different lengths after that. Yes, this/lift is a slant rhyme, but one is the second syllable in the phrase and one is the third. This means it is not a multi because they are not matched in the same location in the phrase. Let me show you a few more examples of actual mutlis, including slant rhymes: Hidden talents Kid with balance Live with malice Broken down as hid­den­tal­ents kid­with­bal­ence live­with­mal­ice See how these rhymes align in the same locations? This is similar to slant rhyming in the sense that your multis can match up as few or as many syllables and sounds as you want, it just dictates how perfect or broken the multi is. One of the best ways to judge if your multis make sense is to read it aloud. Your ear will usually be able to catch what sounds good and what does not. Let’s talk about a strategy for making up your own multis. The easiest way to create multis is to break the words down and then find rhymes for each of the syllables. So if the phrase is common sense, you would break it out into: com­min­sense And try to find words that rhyme in the same areas: Com, Bomb, Mom Min, Spin, Win, In, His (slant, assonance) Sense, Dense, Fence, Tense Then combine them to make a multi: bomb­his­fence Here’s a few more examples: com­pli­ments con­di­ments con­his­ex Again, notice how the examples fall in and out of slant rhyming. Slant rhyming is an essential skill, as it allows you the flexibility to rhyme sets of words that you might otherwise really struggle with. Another thing to remember is that you may want to emphasize certain words in a way differently than you normally do, to make sure the rhymes come out clearly. For example, if rhyming common sense and bomb his fence, you may emphasize the individual syllables a bit more than normal to make the rhyming stand out. One common struggle with multis is clarity. It’s easy to rhyme a lot of words without having any kind of meaning. If this is your intention, that is fine, but don’t let rhyme overtake the message you are trying to portray. Many beginners feel like they need to use so many multis their verses end up making absolutely no sense. As usual, pay attention to what you are communicating and let multis be a tool. Exercise: First come up with 4 pairs of multi­syllable rhymes. The easiest way to do this is think about what phrase you want to rhyme with first. Then break that phrase into separate syllables and try to rhyme the syllables individually. Make sure the multis you select make sense, otherwise, what’s the point? Then pull from your multi­syllable pairs to write 8 lines. Once you’re done, take a look at your lines and see how smoothly they read, usually when it sounds strange that’s when it’s too far slanted. Reading the lines aloud is especially helpful for catching mistakes. Worksheet: 1. Write 4 pairs of multi­syllable rhymes 2. Write 8 lines using these rhymes Supplemental Material: Writing Multis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZcWdD2xkRzc Counting Method: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHb5GfMmFaQ Day 24: Battles & Punchlines Content: Today we’ll briefly touch on battles and punchlines. Battles are a huge part of hip­hop and a way for emcees to go head­to­head, testing their wits against each other. Although there are many ways you can approach a battle, punchlines are what determines the winner. Punchlines are not specific to battles, you can have punchlines in a normal song, but they are absolutely essential to battling. A punchline is the part of your verse that has impact. You can think of it as the line that gets a crowd reaction or ties the previous content together. Again, you can have punchlines in other types of writing. Think of jokes, they also have punchlines. You are doing something similar when you create one in rap. Here’s an example of a punchline: I’m a baker with cash cause not a day go past Where I don’t put in work and have to make dough fast Notice how the end of the last line is what ties everything together and has impact. This particular example focused on wordplay, but punchlines do not necessarily have to include wordplay. As long as you create a line with ‘pop’ then it’s considered a punchline. For battles, punchlines are directed at your opponent The point of a battle is to attack your opponent or show why you are better than them, so each punchline is a point towards that goal. Here’s an example of a battle punchline: You can’t reach my height there’s no need to battle Cause you’ll always be behind me just like my shadow! Notice how these lines are directed at the opponent. The main focus here is how much better I am than whoever I’m battling with, mentioning they should give up because they won’t be as good as I am. It’s the perfect place to say all the mean things you ever wanted. One type of punchlines are personals. These are typically direct attacks at a person’s history, appearance, or actions. Personals make some of the best punchlines because the attacks are based on real material instead of fabricated. Here’s an example of a personal if your opponent is short: Look at him, I bet he’s the ‘hate the carnival’ type Cause you gotta be this tall to get on all of the rides! Now of course with a line like that you would want to use hand gestures to emphasize your point, which brings me into another part of battling. When battling in a live format it’s essential to bring theatrics into the arena. By theatrics, I mean a few tactics to make the battle more entertaining. For example, be animated, speak loudly and confidently, use emotions. A big part of battling is the entertainment factor, so the more you keep attention the better. Another important aspect battling is preparing for the format. Are you going to be writing only? Live? Freestyle? Recorded? The format of your battle plays a big impact in what you need to do to be prepared. Make sure you have prepared in the appropriate ways. If it is written, proofread it. If it is live, memorize your lines. If it’s a freestyle, make sure you know a few things about your opponents so you can make up ideas on the spot. If it’s recorded, make sure the recording sounds the way you want it to, etc. Being prepared is huge in making sure the outcome of a battle goes in your favor. Finally, try to be creative. There are a lot of punchlines and concepts that have been used many, many times. The lines that get the most reaction are ones that are fresh and original. It’s like a joke with an unoriginal punchline. No one is surprised by the content, so at best you might get a slight chuckle. If you want to get some ideas, watch battles and see what kind of concepts you like. As I mentioned before, there are lots of strategies for battling, but punchlines are at the core. Exercise: Start by coming up with 4 punchlines ideas using the best concepts you can think of. Try to imagine battling someone you don’t like and pick out attributes you can make fun of. If you’re struggling to come up with ideas, watch some battles, it really helps get your mind in the right area. Once you have some ideas, work on writing 8 lines and incorporating your punchline ideas into them. The better your setups are the harder your punchlines will hit, so pay attention to how your concepts come together. Battling is a fun way to let off some aggression, be creative and let loose. Worksheet: 1. Write 4 punchline ideas 2. Write 8 lines incorporating the punchlines Supplemental Material: Punchlines ­ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJD30Y8eCIM Personals ­ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ggT9MNxFMmk Nameplays ­ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HJ7_8QzUcU0 Day 25: Storytelling Content: Today we’ll be covering a few aspects of storytelling. Stories are a powerful way to tap into other people’s emotions, communicate a point, or just entertain. The best stories are engaging, bring you to tears, or inspire you to new heights. It’s important when starting a story that you have a plan. A story needs a start, middle, and end. I know this sounds simple, but individuals too often start in the wrong part of their story. They either don’t give enough details to set the scene, or they simply outline a scenario and don’t really explain any events. Or they jump around so randomly, with such sparse details no one can understand what’s happening. When you get to more advanced levels of storytelling you can alter the chronological order of a story, but there always needs to be a plan to make the plot coherent. There are a many sources of inspiration for stories. Your personal experience or the experiences of others are a great source. It is easy to add vital details and recreate the event because it is something that actually happened. It is also easier to keep this type of story coherent, you just retell the events. The other kind of story you can create is fictional. In fiction you have the freedom to explore topics and ideas that would be impossible if simply drawing from your own experiences. This type of story really lets you use your imagination and creativity. When writing a story, it is vital that you create a purpose. What is your story about? Really think about what message you want to convey. Have you ever had someone start telling a story and then realize there isn’t really a point? They just want to talk about random events during the day. This may be fine for casual conversation, but is by no means an engaging story. You need to think of the message or story you want to convey, and develop around that plot. Another important storytelling facet is to create believable and consistent characters. Individuals typically act in ways that are consistent with who they are. Since you are the author, you get to decide the traits of each character. If you create an angry character who suddenly becomes kind, this is hard to understand unless you explain the character’s internal change. Make sure you either keep your characters consistent or explain the chain of the events that led them to different actions. Another important aspect of characters is to convey emotions that make sense for the scenario. If her son gets slapped, a mother is going to be upset, unless you have explicitly set up the mother character in a way that she does not care about her son. People automatically use relationships and other cues to create an idea of how individuals are likely to act. Again, if confusing emotions or actions are not explained, it will be more difficult for the listener to connect. It is also extremely important to actually have an ending. Many stories simply end in the middle without a real conclusion. Make sure your story concludes in a way the listener understands it is finished. If there is a conflict, make sure it is resolved in some manner. You can also add a twist, just make sure it makes sense in the context of the story you’ve developed. Storytelling can be very simple and straightforward and it can also be extremely complex. If this is a skill you are interested in, I highly recommend finding good plots in other mediums like tv shows or books and paying attention to what they do. Storytelling in all these mediums share certain traits, and it’s the best way to learn. Exercise: Come up with a story. Briefly write out the start middle and end and create an outline. This will make it much easier when you go to write the story because you will know what events you need to cover for the story to make sense. You can write this about any topic, it can be as simple as retelling what you ate for breakfast or as complex as a love triangle. Whatever story you feel like creating is appropriate. Then use at least 8 lines to write the story in a rap format. This will be more tricky because to maintain rhyme schemes you will have to use more specific words. Try to maintain flexibility and check your word choice to make sure you are describing the scene well. Try not to let your rhyme schemes overpower the story you are trying to tell, but still use poetic devices to make it sound good. Not as easy as it sounds, but practice is the only way to get better. Worksheet: 1. Outline a story 2. Write that story as a rap using at least 8 lines. Day 26: Developing Flow Content: Today we’re covering an extremely important aspect of rap and that is flow. Flow is the culmination of an emcees style through cadence, syllable counts, and rhyme schemes. Sounds pretty simple, but there is a lot that goes into creating naturally appealing flows. The goal today is to develop a toolset for creating flow. Most rappers gravitate toward a general flow they feel comfortable with, but you can create as many flows as you have ideas. There are many aspects you can alter to change your flow. A few of these factors are the number of syllables per bar, how long you hold sounds, where you leave gaps, how quickly you say words, and how often you rhyme. Different beats will also cause you to change your flow, as you must change your speed to match the beat. As you can see, there are a huge number of options. There is no best or worst flow, what matters is how well the words map onto the beat. This matching dictates the difference between what is considered good and bad flow. When you find pockets in the beat you can fall into and ride, the flow sounds good. When you lose the beat and your words are out of rhythm, seemingly random, the flow typically sounds worse. Some rappers intentionally fall out of rhythm in way that still sounds good, but the key is to know the difference so you are in control of how you come across. Let’s move into ways you can work on developing flow to stand out from others. Of course, one of the best strategies is listening to other rappers that you admire. Find an artist with a flow you like. Listen to them, see how they place their words and how you can emulate what they do. Do they always use the same flow, or do they switch it regularly? Do they rap quickly or slowly? Listening to others will give you ideas for how to place yourself between sounds in instrumentals. Once you have some ideas it’s time to start actually working. Freestyling is the best way I know to improve your flow quickly. Freestyling improves your flow because it puts you on the spot with a rhythm, and when you are not trying to fit specific words, it’s much easier to feel out how words can fit. If you’re having trouble coming up with lyrics, don’t even use words. Think of your mouth as an instrument and try to add complementary rhythms to the instrumental. For this exercise, the sounds don’t have to make any sense at all. You can use complete gibberish, as long as it helps you feel out a potential flow. Once you are comfortable with rhythmic noises, try substituting the sounds for words. Even random, simple, single syllable words will work. Anything to transform the sounds and rhythms you feel into actual words. Working this way, finding the rhythm first then filling in the words, makes it much easier to maintain flow. If you write then try to recite those exact words onto a beat, it can be difficult to know how to flow smoothly. I don’t meant to imply you shouldn’t write first, just that you can use the music first and fill the words afterward. After you have developed ideas for creating one flow, try changing some aspects. Try rapping faster or slower, even on the same instrumental. Create new rhythmic patterns to compliment the instrumental. Try beats that are really fast, and ones that are really slow. Try taking pauses on a different count than you normally do. Each time you change one of these aspects you gain more understand of the tools at your disposal. Once you have a grasp on freestyling and changing flows, it will be easier to modify flow in your writing. Use a few bars with almost no syllables. What do you have to do to make it fit? Write something you have no idea how to flow. That will force you to be creative and learn new strategies. Your flow might sound broken while you try it, but experimentation the best way to learn. All of our discussion so far has been relatively natural strategies for approaching flow but there is also something more techinical known as a flow diagram. A flow diagram displays lyrics broken down by each count of each bar ­ 1,2,3,4. Each new line indicates the start of a new bar. Usually, stressed syllables are bolded. (Stressed and unstressed syllables are not something we’ve covering in this course, but definitely look into them if you’re interested). Flow charts are also typically divided into 4 bars per chart, but can be subdivided into 8th counts as well. Let me give you an example of what a flow diagram might look like for this verse: I rock the beat till I step under the moon No stopping me, I be flexing until noon Go to the hotel when I check into the room My girl keep kissing my neck with her perfume 1 2 3 4 I rock the beat till I Step under the moon No stop ping me I be flexing until noon Go to the hotel when I check into the room My girl keep kissin my neck with her perfume Using this as a key you could create the same flow that I’m thinking of without even hearing the song. You could also map these lyrics on to multiple beats, regardless of the speed. As with rhyme schemes there is not particular way you must build a flow diagram, it’s just a way to map the wording onto an instrumental. It is also a technical way to break down and rebuild flow, if that’s easier for you. Flow is one of the most important parts of rapping, so this is a skill you will want to work on regularly. For most people it’s not easy and takes some time to develop. Don’t get frustrated, just keep working on it, take feedback and learn. You’ll get there. Exercise: First find 3 songs that include flows you really enjoy, and break down aspects of their flow. Do you like that it’s fast? That they draw out and sing their last syllable? Use the skills you’ve developed earlier to identify how the artist flows. After that, pick three instrumentals of different speeds and freestyle to each of them while trying to change your flow during each one, slow, medium, fast. This will help you get used to a variety of instrumentals and speeds, so you can find what comes most naturally to you. Finally, pick a verse and try to map it onto a flow chart. The best way to understand how they work is to build one yourself. It can be difficult to transcribe words and pay attention to the beat, so feel free to use a metronome if you need to. Worksheet: 1. Break down the aspects of flow in 3 songs 2. Pick three instrumentals and practice flowing 3. Pick a verse and create a flow chart for it Supplemental Material: What is Flow ­ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9aWh3b5TJ0M Improving Flow ­ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NsEaQvr4ECo Day 27: Freestyle ­ Rhyming Ahead & Using Beats Content: We’re going to cover a few more strategies for freestyling. For today’s lesson the focus is to think of rhymes ahead of time. It’s a pretty simple idea, as soon as you know how you’re going to end a line, start thinking of words that rhyme with it. So for example you say, “I really like to chill with the big cats”, and instantly start thinking of words that rhyme with cat. Cat, bat, sat, fat. Then you try to find ways to connect those words. So maybe the first thing you think of is bat, then try to think of ways to connect that with cat. Don’t be discouraged if the concepts don’t connect perfectly, something like this is totally acceptable: I really like to chill with the big cats Hit it hard every time, swingin with a bat This might sound a little weak, but for freestyle standards this is fine, especially if you’re first starting out. By focusing your mindset on rhymes you have a much better chance of thinking of one quickly. Singling out this aspect of freestyling and developing it will make it much easier to come up with lines. If you’re really struggling to come up with words between rhymes, use your fallback phrases, that’s what you have them for. So if you said “I really like to chill with the big cats” then don’t know what to say between use one of your phrases like “I don’t care if….” to make something like this: I really like to chill with the big cats ‘I don’t care if’ they hit me with bats A common practice is to focus heavily on your rhymes and use them to bridge together new concepts. For example, if you started with cat, then moved into bat, then you’d start your next concept based on bat. The next line could be something like “I’m at the plate but never gonna strike out”. Then you quickly think of a rhyming word for out. You can potentially continue like this forever. As a beginner, don’t be too worried about the clarity of your content, just try to build your skillset. I also want to talk about freestyling with a beat. Freestyling with a beat is much harder than acappella because if you need more time to think, falling out of rhythm will be more noticeable and sound awkward. So it’s even more important on a beat that you keep going, no matter what you say. When you stop, you immediately lose your momentum. You don’t always have to rhyme (even though that’s our focus for this lesson) but you do need to fill the space with something. You will be amazed at what you are able to come up with, and remember it’s fine if you repeat yourself. When freestyling over beats it’s best to use a variety of instrumentals. By using different tempos and styles, you expand your skill range and challenge yourself. You also learn what styles inherently fit you and your preferences. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes here, as discussed previously freestyles are not perfect. The most important aspect here is to have fun and let loose a little bit. Exercise: First, set a timer for 3 minutes and try the thinking of rhymes ahead of time while you recite your lines, and then chaining them into your next concept. Keep going for that entire period of time, it’s ok if you repeat yourself or make mistakes. As always, remember to deliver the lines in a confident way. The more you practice with a realistic delivery the easier it will be when you actually perform. Pick an instrumental and freestyle to it using end rhymes. It’s ok if the rhymes don’t always hit, but you should always be saying something, even if it’s gibberish or repetitive. By practicing focusing on rhyming, your mind will slowly adjust to coming up with rhymes on the spot. If you need to, write down some lines beforehand with the endings being blank. That way you will already know what to say for one line, but the next line’s rhyme will have to come spontaneously. Worksheet: 1. Freestyle for 3 minutes using the rhyme ahead strategy 2. Freestyle with an instrumental using the rhyme ahead strategy Day 28: Freestyle ­ Opposites & Themes Content: Today we’re covering more ideas to help you keep freestyling. The first strategy builds on yesterday’s work with using the rhyming words to create concepts. The second is to use themes and see how long you can stay with them. Both of these strategies can keep a freestyle alive almost indefinitely once you master them. Many rappers struggle with creating a steady stream of concepts when they first start freestyling. Their lyrics are often repetitive and quickly become boring. As discussed yesterday, you can break this by using concepts complimentary to your end rhymes. For example if you say: She was a sweet girl, always used to be proper We only kicked it with style like street soccer The last word you said was soccer, so you would want to start thinking of related words. Field, goalie, striker, hat trick, etc. Then use that word as your next rhyme: But she never stayed she wanted to play the field Didn’t get enough time for romance to build Then with build you can think of words related to building: tools, skyscraper, contractor, etc. The benefit of this is you can keep chaining into new concepts and keep them related. If you master this, you can always introduce fresh new concepts into your freestyles. Remember, you don’t have to focus just on end rhymes. You can use any word in each line to come up with a new subject. So using the same example you might say: She was a sweet girl, always used to be proper We only kicked it with style like street soccer And instead of focusing on soccer, the you focus on the word style. Then you can jump into a concept based on style like your clothes or an accessory and say something like this: She was a sweet girl, always used to be proper We only kicked it with style like street soccer She really loved the gold shine of my chain Kisses up against the whole side of my face As long as you find a concept to grasp onto and develop, you can keep your freestyles fresh and engaging. A lot easier said than done, but once you learn to focus on these concepts you’ll find there’s plenty to rhyme about. This works especially well if you let yourself be free and skip the judgements. Related to this concept, you can also use opposites to generate concepts. Here’s an example: I like the way she looked, no moment forgot That dress draped over her body, oh so hot Then the opposite of hot would be cold. So you might say something like: But the problem was she gave me the cold shoulder All I ever wanted to do was to hold her Then you could use ‘hold her’ to develop the next concept. The opposite would be ‘let go’ and you could talk about letting go of a dream or something. Again, you can continue using this almost indefinitely. This strategy is also easy way to create contrasts, which catch people’s attention. Although this is much more challenging, another great freestyle exercise is to hold a theme as long as possible. By doing this, you force your mind to focus on that topic and come up with rhyming words in lists organized by that theme. This will make it easier in future freestyles to chain into these topics. One way to do this is to come up with a list of topics you want to use. Once you have your topics, start freestyling as long as you can for each subject, then move on to the next one. For this exercise, it’s ok to take a little more time to ensure you stay on topic, but don’t take too long. Also, don’t be frustrated if you find it difficult, it’s a hard exercise. Alternatively, you can join a cypher and pick a theme for the entire group to use. This is a lot easier because you have many people all thinking of different ways to approach the topic. These sessions are likely to last longer as you can use each other to keep the theme alive. Exercise: For today’s exercise first pick four instrumentals. For the first two instrumentals, freestyle using the opposites technique. You can also combine it with the similarity technique, just make sure to chain each line using content from the ones before. This is the best way to develop the ability to freestyle for long periods of time. For the other two instrumentals, pick a few themes and try to stick with them as much as possible. Since these are going to be pretty long, pick something broad. This will help ensure you have enough material to work with. Again, don’t panic if you find this difficult, it’s not an easy exercise. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, turn the beat off, freestyle with themes acappella, and take your time. Worksheet: 1. Pick 4 instrumentals 2. Freestyle to 2 focusing on opposites 3. Freestyle to 2 focusing on themes Day 29: Finding Beats & Recording Content: Today we’re covering tips for recording tracks and finding instrumentals. This lesson also includes a few topics related to delivery. There’s much to learn beyond this, but today we’ll cover the basics. Also, we will not be covering mixing or producing as they are beyond the scope of this course. Now that you have some baseline skills developed, recording music is naturally the next step. Recording makes it easy to share your music and get feedback. It also helps you hear which skills need improvement and what you’re doing well. Here’s a few things to remember while recording. First, keep your head still, don’t wiggle around everywhere while you record. When you feel the music, it’s easy to move around, bobbing your head, leaning back and forth. This makes for weak recordings as the volume levels will be inconsistent and harder to mix. You want to stay as stable as possible with your head. If it helps, follow the beat with your hand instead, that way you can keep the motion without ruining the recording. Another thing to keep in mind is your distance from the mic. A general rule is about six inches away, although the type of mic and setup makes a difference. If you are recording at someone else’s house or at a studio, ask where the best position is to record from. You don’t want to get too close, because it will be too loud and may make your audio clip (too loud for the microphone to process properly). If you go too far away, the sound will be too quiet and you might get background noise in the recording or lose mic presence. Use six­eight inches as a general rule, and either listen yourself or ask if you need to make adjustments. Also remember to speak from your diaphragm (belly) instead of your nose or head. When you speak out of your diaphragm it tends to project better and give you a more full recording on the track. Using your diaphragm can really help with your mic presence, or presence in general. It also will instantly make you sound more authoritative and powerful. To check if you are using your diaphragm, put your hand on your stomach and breathe in or speak. You should feel it moving up and down. If not, then you’re not using it. Now let’s talk about finding beats. Many rappers don’t know where they can get useable instrumentals. There’s a few common places you can start looking. Also, none of what I am going to tell you is legal advice, use it at your own risk. My best recommendation is to connect with producers, locally or online. By having friends that produce instrumentals you gain a lot. You can draw on their experience with music and gain another person to collaborate and work with. Supportive producers can help push you through hard times, give you new ideas, and work with you to create instrumentals specific to song ideas you have. Rap can be a lonely genre if you let it be, making connections never hurts. Connections aren’t the only way to find instrumentals, so if you struggle with this, don’t worry. The easiest alternative is to start searching online for different sites that have beats. Online beats typically fall in one of the following categories; beats for lease, promotional beats, and royalty free beats. The easiest to find are beats that are for lease. These beats cost money to use, but give you the right to sell any music you create. Make sure to pay attention to the type of lease to know exactly what you can and can’t use the instrumentals for. It’s very important you use these properly to avoid getting in trouble, the last thing you’d want is to get hit with a fee for selling music in a way you shouldn’t. The second kind of instrumentals are promotional use beats. These are basically instrumentals that are tagged by the producer that you are allowed to use for promotional projects. Promotional projects essentially mean you can distribute them, but you are not allowed to sell them. Also, make sure you give credit to the producer for what they’ve created. If you look hard enough you can also find completely free or royalty free beats. These are instrumentals you can use for whatever you want and have absolutely no cost. These are a lot harder to find than the other kinds, but they are out there. Pay attention to what it is you are downloading so you know what you’re dealing with. It’s also good faith to give these producers credit, as they did just give you something for free. In essence, it boils down to this, if you are not selling it, most likely you will be able to use it in your project. That’s why you hear tons of remixes on well established beats. No one will really try to come after you unless you are making money. If you are planning on selling your music make sure to use beats you have the rights to, otherwise you can get into trouble and cause problems. And again, give credit to the producers, they put time into creating this music too. Exercise: Today you should practice recording. It doesn’t matter what you record or how, but play around with a few aspects like distance and see what style works best for you. Your phone or laptop’s internal mic will work just fine. Make a few recordings and listen carefully to the outcomes, make more edits and see what happens. You should also start looking into producer networks, again whether it’s local or online doesn’t matter. Start making those connections and it will be much easier to get music produced and mixed, not to mention build valuable relationships. Worksheet: 1. Create 5 recordings, play with your delivery and the equipment 2. Start looking for connections with producers Day 30: Putting it all together Content: You made it all the way through the entire thirty days, pat yourself on the back! Committing and following through 30 days of anything is impressive. It is a testament to your willpower. I want to thank you for taking this journey with me and listening to the things I have to teach. Today we’ll relax on the skill building and think about everything you’ve done so far. You’ve gone from potentially knowing nothing about rap, to having all the skills you need to approach the biggest facets of rap; writing, recording, battling, and freestyling. These are the fundamentals you need, a starting toolset for rapping. You may not have mastered all the components yet, but you know what they are and have strategies for practicing them. That’s a huge accomplishment for learning a new skill, and a necessary first step. Since the course has concluded, you should be able to identify the skills you’re strongest in and which ones are more difficult. If you have an area that is particularly difficult, you should look for more exercises to build skills and develop your style. Hopefully, you now have a stronger appreciation for the talent it takes to create rap at a high level. You should also be able to break down how other artists use their toolsets, and identify their strongest talents. Now that you have started building habits, you’ll want to keep learning and growing on a regular basis. Rap is like any other skill, to become accomplished you need to practice. No amount of lessons, listening or reading can help you if you don’t actually practice what you’ve learned and implement it. That is the most important part of building any skill, and it applies here as well. Practice every day if you want to improve. Moving on, you should look for places to join the rap community. It can be online or locally, but finding places to share your craft, getting a mentor, and supporting others is a big part of being involved in the art. Being part of a community also makes it easier to stay motivated and find the support you need. If you want a full appreciation of the art, you’ll need to interact with others who are involved. One last thing to remember, rap is an art form. There are no real concrete rules that you must follow. In fact, being completely rigid and formulaic may make you miss out on fully expressing yourself. Art, at its core, is a representation of the artist creating it. Dig deep and find the confidence to create something that is a true representation of yourself and you’ll be proud. Allow creativity to reign freely, and use these tools in the ways you want. We’ve gone over the fundamentals, but it is up to you to infuse your soul into your craft. Exercise: First, write out a list of things you feel like you’ve accomplished and what you still want to accomplish in the future. Part of growing your skills is to always be looking ahead. Again, you really need to practice to develop your talent. Simply listening or reading will not be enough to unleash your full potential so I encourage you to practice on a regular basis and look for ways to learn new skills for your toolset. You should also take the time to compare a verse from when you started to now. See how your style has changed, and notice what you’ve learned. More than likely, you’ll see a lot of differences. Hopefully, you feel like your style has developed quite a bit, and that you have a lot of growth left. There’s always more you can try. Keep working hard and eventually the pieces will fall together. Finally, please give me any feedback you have for the course! It really helps me understand what has been helpful and what still needs work. Just like you, I’m learning to fine tune and create the most straightforward and engaging materials possible. Thanks for participating. Good luck! Worksheet: 1. What have you accomplished in this course? 2. What are your goals for the future? 3. Compare a current verse to a past verse 4. Please give feedback