CHAPTER 10

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

10 Managing digital

business transformation

and growth hacking

Chapter at a glance

Main topics

→>>

The emergence of digital transformation as a discipline

→>>

Understanding the reasons for digital transformation

→

The framework of digital transformation

What is growth hacking?

->>

Defining goals and KPIs

How to use a single metric to run a start-up

Creating a growth hacking mindset

, in digital marketing

Developing agile marketing campaigns

→>>

The growth hacking process

Creating the right environment for growth hacking

Measuring implementation success

Focus on...

→>>

Web analytics: Measuring and improving performance of digital business

services

Measuring social media marketing

Case studies

10.1 Transforming an entire industry and supply chain: Spotify and Spotify

Connect

10.2 Learning from Amazon's culture of metrics

10.3 How Leon used PR to growth hack

Learning reading speed

73%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Web support

The following additional case studies are available at

www.pearsoned.co.uk/chaffey

→ SME adoption of sell-side e-commerce

→ Death of the dot.com dream

Encouraging SME adoption of sell-side e-commerce

The site also contains a range of study material designed to help improve your

results.

Scan code to find the latest updates for topics in this chapter

Learning outcomes

After completing this chapter the reader should be able to:

. Critically analyse the journey of an organisation through transformation

• Review the approaches to be taken in a digital transformation exercise

• Produce a growth hacking/agile marketing plan

• Create a plan to measure and improve the effectiveness of digital businesses using analyt

ics tools

Management issues

The issues for managers raised in this chapter include:

Learning reading speed

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

• When does a digital business need to think about implementing a digital transformation

project?

• What are the non-technical aspects of a digital transformation project?

• How do we gain traction on a limited budget?

.

• What techniques are available to measure and optimise our services?

• Does the organisation have the right culture to support a growth hacking approach?

Links to other chapters

This chapter is an introduction to the evolving ideas around digital business transformation

and growth hacking. It gives a context to the current and future views about how digital busi

nesses are changing and how they are designed, and it also introduces how transformation and

growth are managed. The chapters that inevitably feed into digital business transformation

and growth hacking are:

• Chapter 2 explains customer journeys and business revenue models, which links to digital

.

transformation

Chapter 5 has sections on disruptive innovation and digital channel strategies that are

particularly relevant to this chapter

Chapter 8 discusses the implementation of digital marketing plans, which relates to

growth hacking

• Chapter 9 has a section on customer experience (CX) that links to digital transformation

and growth hacking

Introduction

As we move towards the third decade of the 21st century, organisations are changing at a

faster rate than at any time since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Traditional methods

of thinking about how we manage technology and change have started to unravel. The impact

of digital on organisations and on society means that speed of change is very rapid, and the

impact of change is enormous. Businesses need to make significant efforts in the way they re

spond to change in the environment by operating in different ways to the past. Digital transfor

mation and growth hacking are two approaches on how to handle the change. See Case study

10.1 for an example of how Spotify is responding and then complete Activity 10.1.

Case Study 10.1

Transforming an entire industry and supply chain: Spotify and Spotify

Connect

Spotify was developed in 2006 and officially launched in 2008 as a freemium service to

stream music across the Internet. At the time of writing it remains a service with a free-to

use limited service tier supported by advertising and a subscription model allowing access to

Learning reading speed

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

greater features such as high-quality streaming and song downloads for times when the user is

not connected to the Internet.

Unlike services such as iTunes, Spotify does not sell individual songs to listeners and then

pass the proceeds of sales to artists. Instead, Spotify pays a royalty to artists based on a pro

portion of their income. This model has received criticism from artists and music labels, but

Spotify continues to grow, and music artists find it a very difficult proposition to ignore. Other

services have grown at the same time that offer similar services, such as Deezer and Tidal.

Spotify competes in a busy marketplace and has two significant problem competitors - Apple

Music and Amazon Music. What makes these significant is they are both music streaming

busin ses with a significant hardware proposition: Apple with its iPhone range, and Amazon's

Alexa.

To counter these propositions, Spotify runs Spotify Connect, which includes its Software

Development Kits (SDKs). This approach allows developers of software and apps, as well as

manufacturers of hardware, to incorporate Spotify code into their creations. This embeds Spo

tify into software and hardware, effectively locking in the user of the app or the manufactured

device.

At the time of writing, Spotify boasted of embedded connectivity in more than 300 devices

from more than 80 different manufacturers, including high-end audio systems, in-case enter

tainment and TV platforms, as well as devices such as Amazon Firestick and Google Chrome

cast.

This move increases the number of interfaces where Spotify can be accessed, away from

the two 'traditional' points of interaction - the website and the mobile app. This increase in

the number of interfaces increases the opportunities to interact with the Spotify service. Most

require the premium subscriptions, which logically adds to the company's revenue stream.

Prospective owners of premium devices are more inclined to purchase a specific device if it

has access to additional features. Spotify can be regarded as a desirable additional feature so

manufacturers are keen to incorporate it. This symbiotic relationship is changing the way the

music is managed from artist to listener. By doing this, Spotify hopes to influence the devices

that people buy and also encourage subscription by residing on the device itself.

Spotify has transformed the way people consume music. It has become a verb to represent

how one listens to music (in the same way that the phrase 'to google' became the verb to mean

how one searched for information on the web). The transformation is from possessing music

files (an earlier transformation) to streaming them - a significant alteration in the culture of

music listening.

Activity 10.1

Digital opportunity

Purpose

To identify any new digital opportunities from which any organisation could look to

take advantage.

Activity

• Make a list of any new technological developments that have occurred in the last 12

months that seem to have appeared from nowhere.

1 min left in chapter

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

. Consider what changes are needed by any organisation to adapt to the develop

ment. What cultural, practice or process changes could the technology create?

How would people change?

Base your answers on your own experience of other technological developments and

changes you have observed in culture, practice or process.

Definitions of digital transformation

The definition of digital transformation is contentious - different commentators and theorists

have differing views, and this can lead to some confusion. The confusion comes from opposing

worldviews about what transforming means in the context of digital. People's interpretation

depends on how they view the significance of an intervention in an organisation. For example,

some practitioners might regard the (simple) implementation of a website for an organisation

as digital transformation. Others might see that as too narrow a perspective, because it only

focuses on one 'small' and discrete intervention within an organisation. The key perspective

here is the context - that simple website might reflect a massive change for the organisation. It

is not so much the website that is the digital transformation, rather it is the (planned) transfor

mative effect that it has on the organisation.

Digital transformation can be described as all of the changes that occur when 'digital' is ap

plied to any human endeavour (Stolterman and Fors, 2004). Lankshear and Knobel (2008) have

a slightly different view, and see it as the third stage in a journey that society or a community

must make (the first stages being digital competence and then digital literacy). The definitions

of digital transformation transcend just commercial businesses, and many definitions discuss

similar notions of transformation within arts (Taylor and Winquist, 2002), science (Baker,

2014) and public service (Nam and Sayogo, 2011).

More modern and accepted interpretations of digital transformation are effectively sum

marised by work coming from MIT's Center for Digital Business (Westerman et al., 2011), start

ing from a study where they broke down the notion into two separate strands of thinking - that

digital transformation is marked by a level of intensity of application and implementation of

digitally driven projects, and also by the way an organisation manages change within itself to

take advantage of digital. More recently, there is a clear sense that true digital transformation

is about transforming whole organisations rather than working on isolated, individual digital

projects (Kane et al., 2015).

We're really interested in the sense of digital transformation as it occurs in a business -

whether commercial or in public service - and it's these definitions that seem to make more

sense in the context of digital business.

Definitions of digital business transformation

If we think about digital transformation in the context of a digital business, then we get a more

focused sense of the meaning and purpose of transformation driven by digital. The definition

of 'digital business transformation' has evolved and continues to as the notion of what 'digital'

is changes. But even these newer definitions are varied and contentious.

1 min left in chapter

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Adapting versus adopting

The terms 'adopting technology' and 'adapting to technology' are critical to under

standing digital business transformation. Choosing one term over another indicates a

particular worldview about the role of digital in the business. When a business adopts

a digital technology, the implication is that the organisation isn't changing in any way

- it is merely incorporating the technology into the organisation without any particular

change to the business. Buying new hardware, such as simply supplying new laptops to

the staff of a business where they previously had desktop computers, is merely adopt

ing a new technology. Many argue that this does not represent transformation at all,

and that transformation can only be represented by the adaptation of the organisation

to digital technology. Adaptation implies that the organisation is changing to take ad

vantage of the opportunities that digital can provide.

The Global Center for Digital Business Transformation defines digital business transforma

tion as a journey where businesses 'adopt digital technologies and business models to improve

performance' (Wade, 2015). The use of 'adopt' is contentious, because many businesses adopt

technology without necessarily changing themselves - one might argue that (as has been sug

gested in the broader definitions of digital transformation) businesses need to adapt to digital

technologies rather than just adopt them - yet they themselves as an organisation also go on to

say 'Digital business transformation is organisational change through the use of digital tech

nologies and business models to improve performance' (Wade, 2015).

Forrester (Gill, 2015) defines digital business alone as exploiting 'digital technologies to both

create new sources of value for customers and increase operational agility in service of cus

tomers'. Again, this really leaves out the idea of the 'adaptation to' principle and retains the

'adoption' principle.

Why is digital business transformation

not just about IT?

The question is often asked as to why digital (business) transformation is not just about IT.

This question comes from the assumption that digital is simply about technology, and is very

much linked to the difference between 'adopting' technology and 'adapting to' technology. It is

true to say that an organisation's IT resources (in terms of its IT infrastructure, investment and

support staff) are inevitably going to be linked to any digital business transformation effort.

But it's worth looking at where traditional IT decisions come from and how they differ from

digital business transformations.

The applications portfolio - a precursor to

digital business transformation

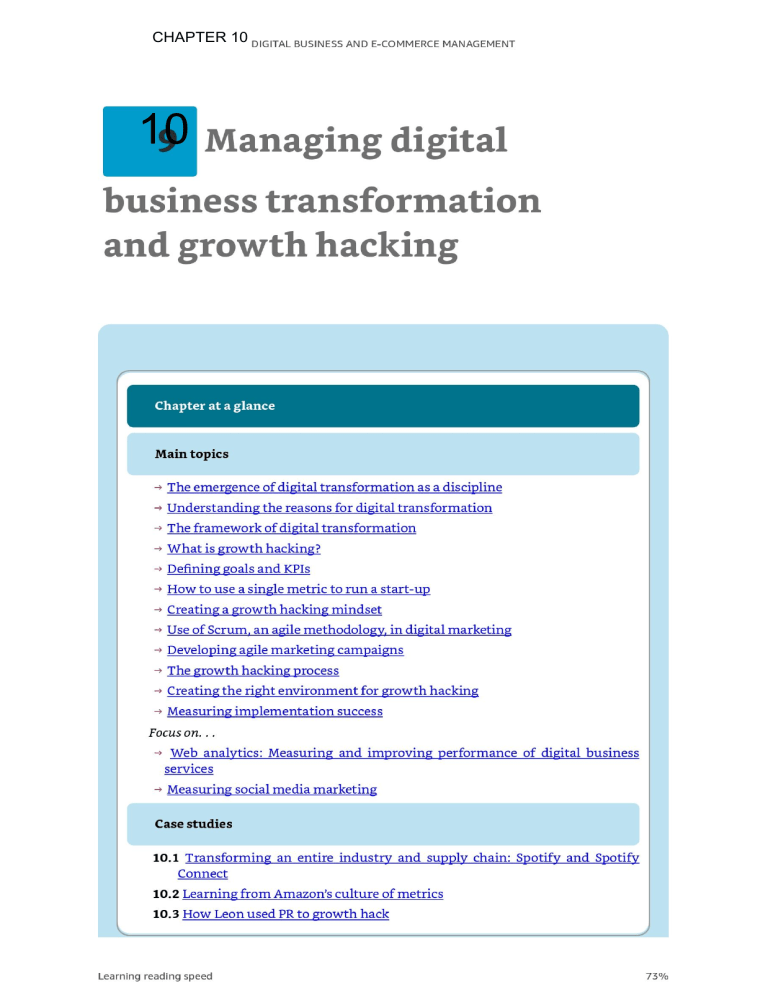

Ward and Peppard (2002) developed a model to understand the role of information technology

in the organisation, allowing managers to understand the significance of technology invest

ment. The role of technology in this model is dictated by the strategic significance placed upon

it by the organisation itself. Ward and Peppard break these technology investments down into

four specific types that allow an understanding of the role they are supposed to play, and these

roles are shown in Figure 10.1, known as the IT Portfolio Grid. It's interesting to note that Ward

and Peppard don't refer to these items as software, programs or IT but as 'business applica

tions' - this in itself is an early step towards the understanding of how digital is involved in the

transformation of business.

Ward and Peppard's view of applications is that they could be extremely large and complex

business processes that contain many IT hardware and software elements, along with de

1 min left in chapter

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

signed elements of data, information and knowledge flows. Business applications in this con

text are whole business processes, not just software, and each application is defined by the role

it plays in the organisation.

1 High-potential applications

High-potential applications are almost always developed 'from within' - even though certain

elements may be imported from external sources, the combined holistic total of an applica

tion will be an in-house development, particularly the way in which all of the elements of the

process are weaved together. The configuration of the process will almost always be unique to

that business. As a result, many of the skills and competences associated with the digital op

portunity may not exist (as yet) within the organisation (or indeed within the outside world)

and so these skills develop at the same time as the project itself.

One of the important facets of high-potential applications is that the business needs to

know when to shut it down. If an application in this quadrant isn't able to demonstrate its

value or potential within a given period of time, then it needs to be closed down. Although it is

not expected for a high-potential to be profitable or to demonstrate any immediate cost bene

fits, the results of analysis must show that there is potential for these to happen. If not, the only

conclusion is to shutter the whole application after all affordable avenues of enquiry, modifica

tion and development have been considered.

STRATEGIC (Attack)

High

HIGH POTENTIAL (Beware)

Business

IT

Opportunity seeking

opportunity

Critical success factors

driven

Demand management

Potential

Complex

Federation

- Organizational planning, multiple

- Business-led, decentralized,

methods based on goal seeking

of IS/IT

driven

Innovation/Experimentation focus

Competitive/Exploitation focus

contribution

opportunity

entrepreneurial or new technology-driven

application

to

Backbone

achieving

Traditional

- Methodical planning, integrated

future

- Evolutionary planning, localized

solutions, centralized control

business

applications, decentrailzed control

Current business performance

goals

- Utility focus

focus

Business

issue

driven

- Efficiency focus

Supply management

Opportunity taking

IT issue

Current problem solving

Low KEY OPERATIONAL (Explore)

driven

SUPPORT (safe)

Low

High

Degree of dependence of the business on

IS/IT application in achieving overall

business performance

Figure 10.1

1 min left in chapter

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Ward and Peppard's IT Portfolio Grid

Source: Ward and Peppard. (2002)

On the other hand, if a high-potential does produce evidence of revenue or value generation

or cost benefits, then the business needs to give consideration as to whether it should invest in

the application and make it a strategic application

High-potential applications are those applications that currently do not provide value to the

organisation, but they may well provide a value at some point in the future. These applications

may be experimental in nature (they could be described as 'alpha' or 'beta' projects). These

are often very new issues not only within the business but to the world in general. They are

often highly entrepreneurial in nature. They are also difficult to quantify in terms of purpose

and scope - the business is really not sure of what they are for. The purpose of high-potential

applications is for the organisation to validate the need and value of a specific aspect of the ap

plication as well as the application as a whole.

A small area of the business may have been chosen to develop a high-potential application and

use it for a short period of time.

2 What makes something a strategic application?

One of the most important features of a strategic application is the need for constant and

permanent improvement. Strategic applications need to remain innovative in order to avoid a

competitor copying the process, or parts of it. So, constant innovation and testing of new im

provement maintains the strategic advantage and therefore strategic dimension of the applica

tion. The danger of a competitor imitating (or worse providing their improved version of) the

application would immediately remove its strategic nature. This danger can sometimes come

when the skills and competencies embodied by the staff associated with a key operational

application leave the business and those staff go on to work within a competitor organisation.

When the strategic advantage of an application disappears, there are two possible routes for

the application to follow - the application becomes key operational or it becomes a support

application.

Strategic applications are those applications where the organisation finds that it provides

some kind of strategic advantage. For a commercial organisation, this advantage may come

in the form of a cost saving, the provision of a service or the development of value for cus

tomers that competitors cannot apply or provide. There is something inherently unique about

a strategic application, and so the component parts have an element of 'secrecy' about them.

Any digital opportunity within the application is likely to be developed within the business

this ensures that the 'ingredients' of the total processes remain unique to the business and

very difficult to replicate. The skills and competencies associated with the digital opportunity

are relatively unique to the organisation, and the business has to give significant thought to

retaining those skills. Other digital aspects of the strategic application may be imported from

external sources but only where these are openly available elsewhere and where there is no

specific advantage in developing these from within. Read Mini case study 10.1 to see how the

Google algorithm is used as a strategic application.

Mini case study 10.1

The Google algorithm as a strategic application

What makes the Google Algorithm a strategic application in Ward and Peppard's defi

nition? One key element is the continuing innovation at Google in 'improving' search

results. There have been a series of 'algorithm updates' where aspects of the way the

1 min left in chapter

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

search engine displays results have changed. These updates have a number of causes - to

improve the results that search engine users seek, to stop imitation by competitor search

engines and to reduce the threat of 'gaming the system' by unscrupulous website owners

and content developers, which would undermine the quality of the results the search

engine provides (the issue of unscrupulous or 'black hat' search engine optimisation is a

story for another book).

Ironically, the search engine algorithm at Google isn't a secret. It's a series of publicly

available patents. However, the way these are used is a matter for internal debate at

Google. Google embodies the process of combining different aspects of the search engine

and ensures that this process is developed and kept in house. Perhaps Google's biggest

headache is retaining the staff it has and preventing them from working with competi

tor firms. But the way that Google combines the elements of the algorithm is what (cur

rently) gives it a strategic advantage. The real key to the advantage is the user data that

Google has collected and how that is applied in the context of the algorithm. That data is

unique and Google has collected (collects) it over many years. Its competitors don't have

access to that rich resource of digital behaviour and must create their own.

3 Becoming a key operational application

As a result, almost all key operational applications are the result of significant testing around

known business and industry needs. With that in mind, it's often the case that specific vendors

may emerge to supply the needs of a specific industry. Those vendors may be small freelancers,

who work on similar projects throughout the lifecycle of an industry's common key opera

tional application, or large suppliers of services. Amazon's AWS (Amazon Web Service) is an

example where a large platform owner provides similar services to different operators within a

marketplace. The business needs are known. All of the operators within the sector need to rely

on a service without which they will be at a disadvantage. In effect, AWS levels the playing field

between the operators. At the same time, there is usually a large pool of talent well acquainted

with provision of skills and competence within a specific sector, which means that staff are

often happy to invest time in becoming proficient in these areas. Problems emerge when the

demand for staff outstrips supply, or when potential staff move on to more interesting or

profitable skills and competences in other areas and industry sectors.

Key operational applications have a habit of becoming known as legacy systems, and so it

can be important for an organisation to constantly monitor a marketplace for changes in busi

ness needs or, sometimes, the opportunity to spot a strategic application that could render an

existing key operational application redundant.

Key operational applications are those applications that are fundamental to the operation

of the organisation in the industry or environment within which it operates. In essence, an

organisation employs a key operational application in order to avoid disadvantage relative to

competitors (who would have the application), suppliers (who would use a process to gain

power) or customers (who would use the absence of the application to dominate or subvert the

relationship with the organisation). Key operational applications are regarded as essential to

the operation of the business within the sector it operates, and so without them the business

cannot function successfully inside that area (see Box 10.1).

Box 10.1

1 min left in chapter

The data centre and key operational applications

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Almost every organisation that has a data centre (with some very notable exceptions)

isn't in the business of providing data centres to other people. Data centres have

formed important parts of organisations where there is significant data processing

- for example banks (core business: handling financial transactions), e-commerce

stores (core business: retail) and logistics firms (core business: delivery). Historically,

organisations needed data centres because there was no provider of data centres - and

so the organisation had to build its own resource to carry out this activity. But data

centre operation was not the core business of the organisation.

At the time of writing (and as mentioned in Chapter 3), there are significant

providers of cloud computing services that can be used to carry out the data process

ing activities of many organisations. These cloud computing organisations have data

processing as a core business of their own - they sell it as a commodity, have estab

lished systems to manage the risk and have investments in technology where the cost

of investment is distributed between customers.

Cloud computing consumption embodies the moment when an organisation has

moved data processing into a key operational application - known business needs,

where there is no advantage to managing one's own data centre. In fact, there might

be an argument to suggest that continuing to manage one's own data centre puts an

organisation at a competitive disadvantage in terms of cost as well as risk to the busi

ness should the data centre fail.

4 Support applications

Support applications are those applications that exist for relatively mundane or legal purposes.

The reasoning behind a support application is to ensure the lowest-cost, long-term solution

to a well-established business need. Support applications convey no business advantage and

(to some extent) their short-term non-availability would not put an organisation at any disad

vantage - more likely it would be an inconvenience. As an example, most organisations have

an established approach to payroll management. One of the facets of a support application is

that it may be easily outsourced to a specialist provider or bureau. A digital opportunity in this

area is often used to significantly lower the cost of the support application. Indeed, provision

of the support application to other businesses may be the digital opportunity for a specialist

business. Microsoft's constant development and evolution of its Office suite of software is its

own strategic advantage - there are relatively few competitors (nothing comes near in terms of

sales volume) - and, as a result, it can guarantee that most office workers globally are trained in

its use. That provides a rationale for its use as part of a support application in the majority of

businesses worldwide (see Mini case study 10.2).

If an application is mandated in a business by law (such as health and safety or financial

compliance) then the business itself will look for the cheapest, long-term solution to that legal

requirement. In almost every case, that application will be provided by an external business

that specialises in its provision, and indeed makes the provision of a digital component of that

application its own digital business opportunity.

Mini case study 10.2

If I am in a digitally transformed business, why am I still using

Microsoft Office?

1 min left in chapter

74%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

This piece of content is being authored using Microsoft Word, yet a quick look on any

search engine or social media platform will soon find you hundreds of comments about

how awful Microsoft Office [and its component applications - Word, Excel, PowerPoint,

etc.] is'. Yet for such an awful reputation, the product line is thriving. It continues to be

the priority enterprise office software package used all over the world. There have been

(and continue to be) plenty of contenders - among them Google's G Suite as a cloud-based

application, Apple's iWork (limited to Apple devices) and Libre Office.

Instinctively, the cost of Microsoft Office should make the other options more attrac

tive. Even with Microsoft's monthly enterprise pricing, it is still twice as expensive as

Google's G Suite. So what makes Microsoft the support application of choice?

The critical issue is the total cost of ownership surrounding training. In Western

Europe and the United States, it's usually a common competency requirement of em

ployees to be familiar with Microsoft Office applications in those environments where

use of such applications is core. Training is usually easy to find and significant numbers

of support staff are available to service the Microsoft Office environment. Compared to

the other offerings, the total cost is significantly lower and the level of effort required to

support it is much lower.

Can it last? Its shift into being a cloud-based application puts it squarely in competi

tion with Google's G Suite. The transformation that we might expect in people's outlook

is not that they need a specific tool in the office but that they have a specific job or series

of tasks to complete. The way for Microsoft to survive in that environment is to place less

emphasis on 'Office' per se and more on creating solutions that allow digitally literate

users to carry out the tasks they need. As users become increasingly mobile and access

solutions via wearables, the traditional face of office software will change - and compa

nies will choose the lowest-cost, long-term solution to their needs.

The emergence of digital

transformation as a discipline

History of change and change management

Digital transformation and digital business transformation are in effect descendants of the

original ideas around the discipline of change management. Change management evolved in

the very early 1960s as a response to the growing understanding of how planned and un

planned change affected the behaviour and attitude of people who worked in organisations.

History is replete with huge waves of change and the effect it had on people in organisations,

none more so than with the arrival of disruptive technologies during the Industrial Revolu

tion. Many lives were lost over the years of the late 18th century and 19th century as workers

and factory owners clashed over the introduction of new technologies that fundamentally

removed the need for people to do the work. The growth of Marxism and Socialism can be

traced back to the experiences of writers who lived and observed the consequences of change in

these times across Europe, along with the growth of mass political parties and the trade union

movement.

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

The first half of the 20th century brought great change but this was to a great extent over

shadowed by the two great wars of the period. It's not until the 1960s that we begin to see the

evolution of the ideas of change management evolve. Early thinking in this field came from the

belief that 'all change is bad' and that the process of managing change allows people to accept

change (Welbourne, 2014). It's now accepted that this model of managing change isn't about

discrete periods of change followed by discrete periods of no change - at the time of writing,

many authors accept that change is a constant state rather than discrete periods of change

activity. As a result, managing change in a modern context is about how people are different to

how they were 50 years ago, and how business is also very different.

Managing change has evolved through the experiences of organisations who made it their

business to manage change in other organisations. Phrases such as business process reengi

neering' emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. These change management approaches were often

noted by their 'top-down' approach to change management. Subsequent research and experi

ence ofthese models and approaches to change management were heavily criticised (Anderson

and Ackerman-Anderson, 2001) as the change centred around changing the business while

still (in many cases) not changing the people.

The contemporary view of change management is that it is very much about managing the

change of people, perhaps more so than managing the change of business. This lends credence

in our digital business transformation thinking to Lankshear and Knobel's (2008) idea that dig

ital literacy and competence have to precede digital transformation.

Many change management writers imply that the two big current drivers of change in or

ganisations are globalisation and technology innovation. Both of these are external motivators

of change, and as a result it implies that change doesn't come from an internal motivation

source such as an organisation's staff (Strebel, 1996) and that many aspects of an organisation,

such as culture, structure and business routine, are set up in such a way that change is very

difficult to create. For digital business transformation projects, we need to look at the transfor

mative effects that digital innovation can have not only on the business in terms of things such

as cutting costs or making a profit, but also on the ability of digital innovation to transform or

ganisational culture, business structures and business processes. Indeed it's the position of the

authors that what makes transformation in a digital business occur (as opposed to a business

simply adopting technology) is the ability of new digital innovations to transform culture,

structure and process. And so this change means that 'digital' takes a new position of strategic

importance within the organisation.

The change in strategic position of

digital versus technology

The evolution of 'digital' shows a distinctive journey from something that is an expensive 'add

on' through the emergence of 'IT management' to the position of the contemporary digital en

terprise where digital is at the heart of the whole organisation.

Many commentators look at the emergence of the World Wide Web in 1991 (and to some

extent some other supporting technologies prior to that date) as the moment when (any) or

ganisations really start to take digital to heart. Historically, technology was a barrier to entry

(irrespective ofthe capability of technology generally) due to the costs of the technology itself.

Massive and disruptive technological change was limited to large corporations and govern

ment bodies that could absorb the costs associated with big technological change. The rise

of the web demonstrated that technological innovation could occur to some extent with very

little associated technology cost. Websites were (and are) comparatively cheap to design, build

and host. The unit costs of emailing millions of people are very low. The ubiquity of supporting

technology means that technology itself is no longer strategic. Technology no longer provides

an advantage in itself. Some might argue that it is no longer key operational and that the very

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

term 'supporting technology' implies that technology really has been demoted, for want of a

better term, to a support application under Ward and Peppard's model. Something else has

adopted the strategic position, and that is the broader 'digital' proposition.

We know that 'digital' encompasses not just technology but also cultures (culture of or

ganisations but also the culture that has emerged 'online' since the arrival of the Internet),

the practices of being online (business practice as well as broader societal practice) and pro

cesses that have been and can be created purely online. The strategic nature of digital is about

adapting to digital technology, culture, process and practice and not just adopting technology.

To an extent, adapting to the technology might well be the easy part of the process. Adapting

an organisation and its people to the cultures, practices and processes that those technolo

have enabled is a more difficult job.

It is the view of the authors that digital business transformation and digital transformation

can be viewed as one and the same thing, and that the process of digital transformation is

about adapting to the technologies of digital through the adaptation of organisations to the

cultures, processes and practices of digital.

The need for digital transformation

A compelling case needs to be put forward for digital transformation. It is clearly a more

complex activity than the simple acquisition and implementation of technology. It combines

all of the issues of contemporary change management with the complex issues of digital. It's

not clear whether digital transformation is a revolutionary or evolutionary process -that's gov

erned by the organisation and its context. It is clearly in many cases not a cheap thing to do, but

on the other hand it does not necessarily become a 'big bang' expenditure issue either. There

are many hidden costs, or costs that cannot be quantified in financial or quantitative terms.

The focus of digital transformation is on outcomes and outputs. Placing digital transformation

at the heart of strategic thinking allows the organisation to set goals at the highest level and

ensures that anything done to transform the business is done with the purpose of achieving

these goals. Digital transformation must have purpose.

The importance of digital transformation has seen the growth of roles in existing organisa

tions at the highest level of leadership, where digital is the key factor in those roles, such as

chief digital officer or chief digital business director. There is some debate as to whether such

roles should exist. On the one hand, digital is important yet remains relatively enigmatic (as

a discipline) to many stakeholders in organisations. Having a chief digital officer indicates the

level of importance at the highest level to observers. On the other hand, if digital is to be so

pervasive and be at the heart of everything that the organisations does, then it should not be re

garded as in the realm of only one senior executive but the responsibility of all. Historically, the

responsibility for technology, computing and IT has been placed by many firms with finance

directors, because early systems were centred around accounting practice and calculations.

Over time the role has evolved into roles such as IT director and chief technology officer - em

phasising the importance of the technology but nothing necessarily beyond that. Roles such as

chief information officer, chief knowledge officer and even chief intelligence officer emerged.

But again these roles do not evoke or represent the holistic view of what digital is; rather they

focus on the application and use of technology in pursuit of business. It is the view of the

authors that all ofthese roles risk losing focus on the full impact of digital technology, culture,

practice and process.

Digital transformation allows the organisation to question the way the business operates,

hence it has its strong routes in change management. At the same time, it also explores the op

portunities provided by digital technology. As such, the digital transformation process should

be an outward-looking process that explores what is possible and then looks for ways in which

opportunities can be applied in the organisation. Those opportunities can be in the technology

opportunities that arise through the adaptation of the business, opportunities provided by the

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

way culture is affected or changed in the digital age, opportunities provided by new practices

that emerge in the digital age or opportunities that are provided through the use of new pro

cesses that have emerged in the digital age. The impact is often huge (which can have serious

consequences for an organisation if not well managed), even if the perception is of a small

change. With that in mind, it's worth understanding that there are a number of common areas

(or reasons) where digital transformation occurs with increasing regularity, within both exist

ing and new (start-up) organisations.

Understanding the reasons for

digital transformation

The opportunities provided by digital

According to a number of writers (Westerman et al., 2011), there are three significant themes

that highlight where the main impacts and opportunities for success exist. These are:

• customer service and service design;

.business and organisational processes;

.business models.

Each of these areas provides its own unique set of opportunities and very specific circum

stances that use the particular elements of what digital is. However, we cannot regard the list

as permanently exhaustive. It should be considered that the future is likely to provide new digi

tal technology opportunities, new digital cultural opportunities, new digital practices and new

digital processes. These may go on to impact whole new areas for opportunity in the business.

Where does digital transformation occur?

Customer experience and service design

The management ofthe interface between the organisation and its customers has evolved over

time and has been managed by businesses historically in a relatively fragmented way. This is

due in part to how businesses in isolation, and as a whole, have developed. There are a series

of different disciplines that govern how people and technology work together. Of particular in

terest to the digital business practitioner, these have evolved from studies in the 'man-machine

interface', through areas such as human-computer interaction (HCI), usability and user expe

rience (UX). But the broader field of the interface between the organisation and the customer

transcends the simple technology interface. Even the relatively contemporary UX field focuses

almost exclusively on design (albeit it a relatively broad view) of technology-driven interfaces

for websites and mobile applications. This particular view of the business is only one of three

key fields within customer experience and service design. The areas that have so far benefited

from digital transformation all seem to loosely fit into customer insight, adding value to offer

ings and customer interfaces.

Customer insight

Customer insight in its simplest terms is the information and knowledge an organisation has

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

about its customers. This insight can come from extrinsic and external sources such as data

collected by other organisations, data from market research or even analytics data provided by

companies such as Google. Internal customer insight comes from the relationships that organ

isations have with their own customers. This can come from explicit sources such as surveys,

where customers are actively canvassed for information, or it can come from more implicit in

ternal sources, such as sales data or analytical data about customer behaviour.

Customer insight can occur at the granular level about individual customers or it can be at a

group level and be about whole customer segments. Individual customer data can come from

external sources, such as electoral records or credit-scoring companies, or it can come from in

ternal sources such customer records or purchase histories.

Organisations have collected data, information and knowledge about their own customers

for many years, but it is only in recent times that the insight has been actively used and ex

ploited to improve customer experience and, by implication, to improve the circumstances of

the organisation itself (see Mini case study 10.3).

What do we mean by customer insight and digital transformation?

If we take our definition of digital transformation from earlier ('adapting to digital technology,

culture, process and practice'), we need to effectively ask this question: 'How can we adapt

to digital technology, process, practice and culture to use customer insight?'. To use customer

insight more effectively, the organisation needs to change in one or all of those areas. The

organisation may need to adapt to new technology, adapt to new processes, adapt to new prac

tices or alter its culture to take advantage of customer insight. The biggest problem for organi

sations historically is not that they do not have customer insight, but they are not set up to take

advantage of the insight they have. As a result, insight has often gone unused and unexploited

(and still does). The risk for businesses is that they don't know what customers want or what

they are like, and as a result they may be making mistakes or missing out on real opportunities

to provide what customers want.

Mini case study 10.3

Hertz marketing

In 2016, global vehicle rental firm Hertz needed to find a way to improve the perfor

mance of its sales and marketing function. It wanted to try and get more from the

money it spent on analytics and search engine marketing and a greater return on the

media spend in online advertising in different platforms.

Hertz, like many businesses, realised that data about customers came from many

sources and in many formats. Knowing where this information came from allowed

Hertz to know about the journey each individual customer makes when engaging with

the organisation. This is important, because there can be a belief that a particular ap

proach to marketing doesn't convert if viewed in isolation. There was a need to digitally

transform the aspect of customer insight into a single view of the customer (rather than

lots of different views of the same customer being held on different systems and man

aged by different parts of the business).

Hertz used the opportunity to transform the way it collected, held and analysed the

data from customers, so that it could create a holistic view of the customer wherever

they interacted with the firm. This meant that it could streamline its marketing effort

and get greater value from improving the right advertising and marketing messages to

the right potential and repeating customers.

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Hertz was able to understand a lot more about which marketing actions could at

tribute sales. Instead of simply looking at single marketing actions (such as clickthrough

rates on adverts), combining views on all the actions meant that it could see that many

different marketing interactions would be used to bring a customer to the organisation.

Adding value

The term 'value' is loaded. It's far too easy to think of it as an issue around cost and price, but

the notion of value isn't about price as such (although that may well form part of the issue). It's

sometimes better to use the term 'benefits' rather than value. If we say, 'How do we add bene

fits to our offering?', it sometimes makes a lot more sense.

There are many ways to add value (and these often involve having access to individual

customer insight). Customers like to receive some kind of reward (either financial or non

financial) for their purchase or loyalty to an organisation. Customers like to be reminded of

certain things about the organisation, for example when a sale is due or when goods that they

have ordered are about to be delivered. Customers like recognition of their behaviour, such as

loyalty. Customers like to receive support towards making a purchase as well as after a pur

chase. They also like to receive help and advice on making the purchase itself, such as recom

mendations of purchase choice or options available.

What do we mean by adding value and digital transformation?

We need to ask our question: 'How can we adapt to digital technology, process, practice and

culture to provide value??. It's clear that having access to customer insight is critical, so that

stage of transformation may be a priority. To add value, the organisation needs to consider how

to adapt to new technology, adapt to new processes, adapt to new practices or alter its culture

to provide customer value (see Box 10.2). The biggest problem for organisations is that they

may not use customer insight to inform themselves about what value customers seek to derive

from their products and services. As a result, customers may remain with unmet or under

served needs.

Box 10.2

Customer value in digitally transformed organisations

DPD sends its customers a series of SMS text messages about their imminent delivery.

As the time of delivery gets closer, customers receive a message letting them know

about the window for delivery. Customers can interact and change the date or loca

tion for delivery. This creates greater satisfaction for end customers but it also re

duces the number of missed deliveries by the courier.

Loyalty schemes exist in almost all retail organisations but some organisations

move them into new levels. Sephora uses customer insight to drive different levels of

reward based on different spend levels. Higher spend levels kick off different rewards,

all of which are influenced by the recency, frequency and monetary value (RFM) of

the spend. This creates different communications and different offers for each indi

vidual customer.

Many organisations provide personalised customer support to existing customers

with known credentials. Many customers can deal directly with an organisation

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

through a dedicated chat mechanism on an app or website. In many cases, the first

line of enquiry might be via a chatbot before a case is escalated to a real human. Or

ganisations report that many simple queries can be supported this way, allowing for

simple issues to be dealt with quickly. This creates greater customer satisfaction and

allows organisations to reserve human intervention for more exception-based, spe

cialist interaction with customers.

Spotify provides a new playlist - Discover Weekly - every week for its listeners that

takes their personal song-play history and links that to other listeners who have sim

ilar listening habits. On that basis, Spotify recommends new songs for the listener

th its algorithm believes would be most suited to that listener.

Interfaces with customers

The word 'interface' can sometimes be difficult to comprehend because of its recent use in the

context of computing. As a result, for many people it simply means a screen on a computer. But

interface has a far more simple and less technological interpretation: interface should simply

represent the place where two parties interact.

The growth in computing since the early 1980s has allowed the word interface to be

hijacked somewhat and interface was increasingly used to describe the point where humans

interact with technology. The fashion in the 1980s and 1990s was to talk about the human

computer interface and as a result it's this particular meaning that has taken hold in modern

consciousness. That doesn't mean that it is inaccurate. The emergence of the World Wide Web

allowed commentators in the mid-1990s to talk about a company's website as the interface

between customers and the organisation. This was an increasingly more accurate idea of an

interface but it still really linked a computer to the idea. Add the growth of mobile and mobile

apps to the mix and the talk is still about improving the interface - the very surface or visible

top layer of a computing application, rather than a discussion of the point where an outsider

comes into contact with an organisation.

When we move away from the technology idea of interface, we can actually make a lot more

sense of the discussion of the term in the context of digital transformation. A simple paper

form is an interface. The moment a person calls a company's contact centre or walks into a

high-street store and talks to a member of staff at a cash register - they are experiencing an in

terface with that organisation. Interface truly means any situation where the individual comes

into contact with the organisation - this view of interface makes it far easier to think about

opportunities for digital transformation. In recent years, the phrase 'touch-point' has been

suggested as an alternative to the word interface in order to shift the focus away from existing

technology and the idea of a screen. And humans experience many different touchpoints with

an organisation even during a single interaction with that business. The word interface itself

could refer to a cohesive and planned arrangement of touch-points that a person experiences.

What do we mean by interfaces with customers and digital transformation?

We need to ask our question: 'How can we adapt to digital technology, process, practice and

culture to change and improve the interface with customers?'. These four elements provide an

opportunity to change (or create from scratch) new 'interfaces' between the organisation and

the customer. What digital technology can the organisation adapt to provide an interface with

its customers? What processes and practices need to change to provide that interface? What

digital cultural changes does the organisation need to adapt to in order provide a digitally

transformed interface? The biggest problem for businesses is that they do not use customer in

sight to inform the organisation about the interface that customers (see Box 10.3).

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Box 10.3

Interfaces in digitally transformed organisations

Back in 2007 the BBC launched the first version of its iPlayer (having been trialled for

two years with specific users with certain Internet service providers), which evolved

over the following years to include greater functionality and availability on different

platforms. Its initial launch back then allowed people to watch TV programmes that

had been broadcast on the BBC on Windows machines.

iPlayer has evolved significantly over time. But it's not the technological develop

ment that makes it interesting, it's the evolution in practice, process and culture that

underpins the iPlayer's journey.

There are key moments that give us an idea about this. The main one is how

people's behaviour regarding viewing habits is radically changing. There is a clear

shift from watching live broadcasts of programmes to the consumption of recorded

content via streaming platforms. The second is the proliferation and variety of plat

forms on which streaming content is consumed, from mobile devices through games

consoles to smart TVs and set-top boxes for satellite, cable and over-the-air. Each of

these platforms represents a view on the interface between the BBC and its viewers.

Some of the processes and practices behind iPlayer remain steadfastly 20th cen

tury - not because of any issue with the BBC or the iPlayer per se, but because of the

issues around copyright and the way the BBC is funded through the TV licence. It's

possible that changes to these matters may affect the way the BBC deal with the fu

ture of the iPlayer. What's clear is that it is an interface that BBC viewers use a great

deal. So much so that the entire catalogue of BBC3 programming is now only ever

available through iPlayer, having previously been a broadcast TV channel.

Business process

What business processes have emerged that are products of 'digital'? Technological develop

ments mean that certain processes within the organisation can be speeded up - but what hap

pens when those processes are no longer required? One of the biggest criticisms of digitisation

of process is that the very same process that existed as a manual process is simply the same

process shifted onto a digital platform.

Automation of business process

In a digital transformation context, the automation of business process should not simply take

the existing process and digitise it. The transformation is about changing the process entirely

and allowing the organisation to take advantage of a digital opportunity to adapt to the tech

nology rather than simply adopt it. Automating an existing process is likely to almost entirely

avoid any advantage associated with automation. The process needs to be rethought so that

steps in the process itself can be changed, added to or completely removed if they do not need

to be there. Practitioners talk about the removal of steps or touchpoints within processes. Busi

ness processes can be questioned in the context of the digital transformation process.

Key drivers to automate processes are often about the time taken by existing information

intensive processes. Banking and insurance (see Box 10.4) are often cited as examples where

the time taken to approve a bank loan or an application for insurance cover has dropped from

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

the traditional 'days' to minutes. The critical measure in some cases was that the same infor

mation could be used in different parts of the process - historically, things might have to be

entered as data several times, whereas now they can be entered once and those data can then be

shared (legally) to different parts of the whole process.

Box 10.4

Digital transformation and change to the insurance sector

Domestic insurance purchase, such as car or house insurance, has changed dramat

ically since the 1970s. Originally people would buy a policy via an insurance broker,

who would have direct contact with a number of underwriters. People did not li

aise directly with insurance companies themselves. When a claim was made, people

would deal with a broker.

In the late 1980s, with the arrival of call centres, insurance companies began a

process of disintermediation and removed the step of insurance brokers by allowing

customers to contact insurance companies directly for the purchase and manage

ment of insurance policies.

The arrival of websites soon removed the need for people to ring call centres.

It also allowed insurance companies to move the job of data entry from insurance

employees onto the customers themselves. The time involved for customers was not

dissimilar to the time spent making a phone call. The cost-saving for insurers was

dramatic.

However, this change in process also meant a proliferation of online insurance

companies, which meant that, in order to explore different offers, customers would

have to apply the same information for each insurer - a time-consuming action. New

insurance companies had to compete through expensive advertising just to be con

sidered by potential new customers. Cue the arrival of the insurance comparison site.

Comparison sites allow customers to enter their information once and for numer

ous companies to 'pitch' a price and a proposition. This allows many companies to be

considered but it also means that the competition for customers becomes extremely

tight.

The current model within many national economies is for insurance underwrit

ers to offer only some of their products through comparison sites but to then make

certain other products only available through their own websites. The change of

process over time to take advantage of a digital opportunity has had mixed blessings

for insurers. At the same time, customers now have to consider several different com

parison sites. Until very recently, Google was offering insurance comparison in its

European search engines through small apps in the organic results page for searches

around insurance, until a legal ruling by the EU rendered this as an anti-competitive

practice.

The product (an insurance policy) has altered very little, but the process required

to obtain one has changed a great deal in 40 years.

The business model

What business models have emerged that are products of 'digital'? Technological develop

ments mean that certain business models have emerged that were not possible previously.

1 min left in chapter

75%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Changes to

culture, practices and processes also mean that ex

new business models can be

plored and exploited. But what business models are changing?

• 24/7 anywhere: the idea that customers can access an organisation at any time of the day

and from any location. As an example, Amazon's storefront is permanently open and you

can purchase from Amazon anywhere in the world where there is a delivery or postal

service.

• A move away from 'What can I sell you?' to 'What do you need?': the idea that a focus

on customer outcomes rather than a focus on the organisation's products is critical. As

an example, Strategyzer's value proposition design (VPD) model forces organisations to

focus on customer 'jobs', 'pains' and 'gains' rather than on product features when consid

ering how a business model should work.

• A move away from assets and a move towards access to services: the idea that it is not

about owning physical assets that is key, but that it is possible to connect people who

own those assets with people who want access to those assets. As an example, Airbnb

does not own any hotels or properties but operates a reservation system for short-term

lets in private properties.

You will see (and we have discussed some of them earlier in this text) a whole series of

examples where the digital business has transformed a marketplace by adapting to a digital

opportunity. At the time of writing, services such as Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Prime Music

and Google Play Music all connect users using different devices who want to listen to music

from an enormous catalogue of artists. The business model of buying physical music assets

(such as CDs, tapes, mini discs and vinyl) becomes redundant for the consumption of music -

although there is a remarkable market around the purchase of physical music assets. The key

feature of streaming and instant accessibility removes the need to physically possess music.

The business model in the music industry based around the sale of physical music assets has

dwindled enormously. Culturally, there is a shift to listening to music on demand and away

from possessing media containing music. The same shift in culture is reflected in the con

sumption of video media. There has been a cultural shift away from viewing live broadcast

media and owning media containing video content to viewing streaming video on demand.

This digital cultural shift influences and creates the business model of organisations such as

Netflix or NowTV as much as the digital technology enables it - one might argue that the digital

cultural shift occurred earlier than the availability of the digital technology with the growth

of consuming pirated music and video content in the 1990s and early 2000s (LUIS and Bertin,

2013).

New business where digital is at the heart of the opportunity

We've spent some considerable time emphasising that the key driver to digital transformation

is not just about technology. However, this does not exclude the situations where the arrival

and emergence of a new digital technology creates a chance for the creation and transforma

tion of a new business opportunity.

The development and maturing of smart mobile phone technology, along with the develop

ment environments for app creation, 3G and GPS together created the perfect conditions for

the creation of the Uber app in a marketplace where there was an unmet or under-served need

for a ride-hailing service. Uber would not have been possible without those four technology

conditions, even though the business opportunity itself may have lain dormant for some time

as an unmet need. See also Mini case study 10.4.

Mini case study 10.4

1 min left in chapter

Digital technology at the heart of the business opportunity

76%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

Mobike is a bicycle-sharing company that originally started in China and (at the time of

writing) now has operations in the UK and Europe.

Bicycle sharing is not new as a concept - but original ideas around this idea resulted

in solutions in London with a cycle hire scheme (currently called Santander Bikes as a re

sult ofsponsorship from the bank) in 2007 and Vélib in Paris. These approaches required

expensive infrastructure investments around locking and payment systems. Bicycles

are expensive and as a result their spread has been limited to significant major capitals

and conurbations.

Mobike was able to centre its opportunity around the Mobike app. The app is at the

heart ofthe business opportunity. The app controls membership, payment and controls

the locking and unlocking of Mobike bicycles. This removes the need for expensive on

street locking and payment system infrastructure. Locking of the bicycle is managed by

an Internet-enabled lock, rendering the bicycle unusable without access to the app or

physically damaging the bicycle.

It's easy to think of Mobike as a bicycle business, but the argument is that it is a

mobile app business that enables the use of a physical asset. It's possible to think of

other applications for the app where access to a real-world asset for a short time can be

enabled through an app. In that sense, it is a membership system that provides 'keys' for

unlocking services and products. The app is at the heart of the business opportunity.

Adapting the existing business to a digital opportunity

Transformation, as a word, seems to indicate the previous existence of something else. Oppor

tunities for transformation are going to exist in organisations already in operation (see Mini

case study 10.5 for example). So digital transformation in this instance, rather than creating

new business around a digital opportunity, refers to the adaptation of an existing business

around a digital opportunity. We've talked previously about the need to adapt the business to a

digital opportunity rather than simply adopt digital technology.

Adoption is simply the acquisition of a technology into a business. In many cases, organ

isations adopt technology because it is fashionable, new, 'shiny', or because they are worried

about being 'left behind'. The problem is that this does not necessarily make a digital business.

It just means they have technology but they might not be benefiting from it - it could be

making things worse. Adoption can be an indicator of a lac strategic thinking - rather than

ascertaining what the goals are (what do our customers want, what do we (want to) sell or pro

mote, what are we trying to achieve?), the technology is going to determine what the goals are and these might be at odds with what the business wants to achieve. Adopting technology can

indicate that the opportunities afforded by digital culture, practice and processes are missed.

Without these, it could be an issue that means the maximum return (financial or other) from

technology isn't achieved. The goal of digital transformation is to adapt the business so that

it can take advantage of digital culture, processes and practice and maximise return on digital

technologies.

Mini case study 10.5

1 min left in chapter

Domino's Pizza as a constantly transforming business

76%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

On the face of it, Domino's Pizza could appear to be a relatively traditional fast-food fran

chise and chain business. It's based in real-world premises and relies on pick-up of real

product from its premises by customers or delivery to customers using delivery staff.

But Domino's has long had a digital culture of looking to where customers might

be in terms of communication and delivery channel. There is a view that the younger

audience that Domino's seeks to target could be more likely to inhabit newer channels

of communication and retail opportunity. Moving away from the traditional channel of

calling on the telephone for a pizza, Domino's was one of the first organisations that

allowed takeaway food to be ordered from a website. Domino's Anyware platform ap

proach is about enabling a customer to use any channel they desire to order pizza from

their local store.

There are the inevitable mobile and tablet apps, but even these (at the time of writ

ing) contain features that smooth and ease the ordering process. Domino's encourages

the creation of 'Pizza Profiles' and 'Easy Orders' - fundamentally, customer preferences

that can be used for retained customers.

Dependent on location, voice commands in the Domino's app can create a swift pur

chase. Easy Orders can be ordered in 10 seconds using the Zero Click app, or through any

one of the voice channels to which Domino's has adapted its ordering process - including

Amazon Alexa and Google Home. There is even an integration via Ford's SYNC AppLink

to allow in-car ordering.

These public-facing customer-driven channels dictate the strategy - go where they

are, operate how they want to operate. This constant state of transformation means

adapting to new processes, cultures and practices (consider how pizza might be ordered

from Slack), and only then is the technology itself given the light of day.

(Refer to Chapter 9, p. 454 for an interview with Nick Dutch, head of digital at

Domino's Pizza UK, on how they create digital experiences.)

Source: https://anyware.dominos.com/

The framework of digital transformation

There are many organisations that purport to have the winning formula for digital transfor

mation. There are plenty of consulting firms with proprietary methodologies, but there are

common themes of process that run through all successful digital transformation projects

(Nylén and Holmström, 2015). One thing that is worth noting is that a framework for digital

transformation can appear linear, compartmentalised and seem to be designed to run once. On

the contrary, the themes we discuss below are iterative, with activities feeding back and for

ward through the process. And it is an ongoing, constant process, which some liken to a never

ending journey.

The process of review

Successful digital transformation projects do not dive straight in and start innovating or im

plementing - we have previously seen the consequences of technology-first activity, when no

thought has been given to the strategic and business issues within the business. As with any

1 min left in chapter

76%

DIGITAL BUSINESS AND E-COMMERCE MANAGEMENT

proper strategic process, the process of review phase is used to establish the current situation

of the organisation - but this strategic review has some specific components.

As we've mentioned earlier, the process of digital transformation can be initiated because

there is an opportunity to place a digital innovation at the heart of the organisation -remem

bering that innovation can be around digital technology, digital culture, digital practice or dig

ital processes.

So, at this review stage, the organisation probably needs to look at four issues:

• What the digital opportunity is.

• How sure the organisation is of the opportunity.

.

• What level of digital the leadership of the organisation possesses.

• How mature as a digital business the organisation sees itself.

.

These issues are reviewed in tandem rather than in series - they are part of an integrated

process.

What the digital opportunity is

Identifying the digital opportunity should come as a consequence of regular environmental

scanning. The unique nature of digital means that the evolution of technology, culture, pro

cesses and practice is extremely fast and (at this stage in history) very difficult to predict.

This digital scanning activity should involve not only the collection of information about new

technologies, devices and channels, but also intelligence about new skills and capabilities that

contribute to digital practice. The digital scanning activity also needs to collect information

about digital cultural changes, as well as innovations in digital processes. It's very easy to get

fixated on the technology, but the scanning activity needs to look beyond that.

How sure the organisation is of the opportunity

It is very easy for evangelists within an organisation to get carried away with the excitement

of a new digital innovation. As we've mentioned previously, this has historically led to busi

nesses getting involved in technologies that aren't aligned with the strategic views of the or

ganisation. This part of the process is intended to ensure that the digital opportunity can be

expressed in tangible terms for opportunity for the business and whether the organisation can

be assured of its success.

Opportunity analysis will look at questions that are quite traditional in thinking, such as

(but not an exhaustive list):

• Is there an opportunity to grow the business with existing customers or new customers?

. What are the kinds of revenue we can forecast or expect?

• What value can this create for customers?

Success assurance looks at more internal issues and, again these are quite traditional in their

thinking, such as:

• How stable, permanent and reliable is the new technology, culture, process or practice?

.

. Can the opportunity be scaled up?

• How safe is it for the business to adapt to this digital opportunity?

Both opportunity and success assurance approaches may already be existing activities

within the organisation's strategic review process, or they may require some alteration to en

sure they are included. For greenfield developments or start-ups, part of the process of becom

ing an organisation will be to develop this as a robust strategic activity within the business'

strategic thinking.