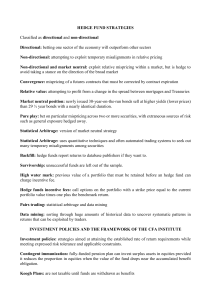

Asset Pricing Giacomo Morelli Introduction 2023-2024 2 Teacher and Lectures ➢ Giacomo Morelli: morellig@luiss.it ➢ Teaching Assistant (TA): • Vittoria Di Felice: vdifelice@luiss.it ➢ Lectures: • Monday 14.00-15.15 (online, virtual room Webex) • Tuesday, 11:00-12.30 (campus, Room Polivalente) • Friday, Gr 1, 11.45-12.45 (campus, Room A401) • Friday, Gr 2, 10:45-11.45 (campus, Room A203) 2 Organization ➢ There will be lectures as well as empirical exercises with data from financial markets ➢ Background in Quantitative Methods for Finance is required ➢ You are supposed to work in groups (max 5 students) on weekly problem sets (PS) that will be subject to evaluation. Solutions to PS will be discussed in class. Students’ participation during lectures is essential ➢ There will be 3 Intermediate Assessments (in groups) ➢ You are supposed to use Python ➢ Final award for the best group ➢ Final exam ➢ Thesis (topics etc…) 3 Learning Verification Method ➢ Attending students: • Class participation 10% (valid only for May-June) • Intermediate Assessment 60% (valid only for May-June) • Final exam 30% (valid only for May-June) ➢ Non attending students: • Final exam 100% 4 Study Materials ➢ The main reference textbook: • Lasse Heje Pedersen. Efficiently Inefficient. How Smart Money are Invested and Market Prices are Determined. Princeton University Press ➢ Other reference textbooks: • John C. Hull. Options, Futures and Other Derivatives, Pearson (9th Edition) • Bodie, Kane & Marcus – Investments, McGraw Hill (10th Edition) • Y. Hilpsch, Derivatives Analytics with Python: Data Analysis, Models, Simulation, O’Reill ➢ I will discuss the required readings at the beginning/end of each lecture ➢ Slides: • Current trend is learning only through slides. Please, don’t 5 Dublin Descriptors Knowledge and understanding: By the end of the course, students should be able to: • understand risk-return relationship, market ef ciency, investment strategies derivatives; fund management, asset price dynamics; • collect, analyse, model and critically interpret investments related to business; • use the software Python for investment analysis. Applying knowledge and understanding: Upon completing the study program, students will be able to: • use asset pricing models; • use nancial thinking to formalise complex problems and apply analytical tools to solve them; • develop investment decisions; • coding. fi fi 6 Dublin Descriptors II: Making judgements: • face complex problems and apply analytical tools in an independent way; • give original interpretations to the results obtained from the data analysis; • these are requirements that students develop during the weekly problem sets. Communications Skills: • develop the ability to communicate in written form through completing weekly assignments and participating to class discussions; Learning skills: • analyse risk-return, market ef ciency, arbitrage opportunities; • autonomously understand and interpret new more advanced techniques and adapt them to the speci c reference context; • problem solving; and decision making; • use the acquired knowledge to access to prominent job positions within hedge funds, investment banking, consulting companies and institutions and/or to access to further advanced learning programs such as PhD or Master’s in Finance or Management. fi fi 7 Objectives ➢ Discuss market efficiency and asset price dynamics ➢ Provide insight into the relationship between risk and return to develop investment decisions ➢ Equip students with a solid background in the different investment strategies in: • Assets market • Derivatives markets ➢ Collect, analyse, model and critically interpret investments related to business ➢ Focus on fund management ➢ Use the software Python for investment analysis ➢ Use asset pricing models ➢ Use financial thinking to formalise complex problems and apply analytical tools to solve them 8 Overview ➢ Market efficiency ➢ Risk-return relationship ➢ Derivation of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) ➢ Hedge funds and other smart money ➢ Overview of hedge fund styles and strategies – – – – – Equity Strategies Arbitrage Strategies Macro Strategies Fixed-income arbitrage Investment styles and factor investment ➢ Derivatives (Options market) 9 Market Efficiency ➢ Market efficiency: at the heart of financial economics ➢ Nobel Prize 2013 awarded to Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, and Robert Shiller ➢ Efficient! ➢ Inefficient! Efficient Markets? Markets cannot be fully efficient 1. If they were, there would be little incentive to collect information (GrossmanStiglitz, 1980) 2. Logically impossible that both market for asset management and asset markets fully efficient – Asset market efficient ! no one should pay for active management ➢ Failure of the Law of One Price, e.g. – Asset management: Closed-end fund discount, ETFs – Stocks: Siamese twin stock spreads – Bonds: Off-the-run vs. on-the-run bond spreads – FX: Covered interest-rate parity violations – Credit: CDS-bond basis Not subject to “joint hypothesis problem” ➢ Completely Inefficient ➢ ➢ 3. Clear evidence against market efficiency EFFICIENCY-O-METER Perfectly Efficient Inefficient Markets? Market prices cannot be completely divorced from fundamentals 1. Money managers compete to buy low and sell high 2. Free entry of managers and capital 3. If markets were completely divorced from fundamentals – Making money should be very easy – But, professional managers hardly beat the market on average ➢ ➢ Completely Inefficient ➢ ➢ Perfectly Efficient EFFICIENCY-O-METER ➢ 5 Efficiently Inefficient Markets Markets are efficiently inefficient ➢ Markets must be – inefficient enough that active investors are compensated for their costs – efficient enough to discourage additional active investing ➢ Investment implications – some people must be able to beat the market Efficient market hypothesis Investment Implications Passive investing Inefficient market Active investing Efficiently inefficient markets Active investing by those with comparative advantage ➢ ➢ Completely Inefficient ➢ Market Efficiency Efficiently Inefficient Perfectly Efficient EFFICIENCY-O-METER ➢ 6 Efficiently Inefficient Markets: Trading Strategies vs. Finance Theory ➢ Finance theory tells you what the price of stocks and bonds “should” be ➢ What if the market price is different? – Model is wrong or market is wrong? – What can you do about it? – How can you tell? 14 What is a Hedge Fund: Definition I “Hedge funds are investment pools that are relatively unconstrained in what they do. They are relatively unregulated (for now), charge very high fees, will not necessarily give you your money back when you want it, and will generally not tell you what they do. They are supposed to make money all the time, and when they fail at this, their investors redeem and go to someone else who has recently been making money. Every three or four years they deliver a one-in-a-hundred year flood. They are generally run for rich people in Geneva, Switzerland, by rich people in Greenwich, Connecticut.” — Cliff Asness, Journal of Portfolio Management 2004. 15 What is a Hedge Fund: Definition II ➢ Hedge fund: – investment vehicles pursuing a variety of complex trading strategies to make money – “hedge” refers to reducing market risk by long/short investing – “fund” pool of money ➢ Can use sophisticated investment strategies and fee structures: – – – – Leverage Short selling Derivatives Incentive fees (mutual funds are restricted) ➢ Limited disclosure requirements ➢ To achieve this relative regulatory freedom, hedge funds are – Restricted in how they can raise capital – Non solicitation – Investors must be “accredited investors” 16 What is a Hedge Fund: Historical Background 1949 Albert Wislow Jones starts the first U.S. hedge fund 1966 Fortune: “The Jones Nobody Keeps Up With” (written by Carol Loomis) coins the term “hedge fund” publicizes Jones’s results: Over 10 years, he had outperformed best mutual fund by 87% 1966-69 Increased hedge fund activity: More than 130 hedge funds started, including George Soros's Quantum Fund and Michael Steinhardt's Steinhardt Partners 1986 Institutional Investor report that Julian Robertson’s Tiger Fund has averaged 43% per year for 6 years 1990Institutional investors start to embrace hedge funds (including the Yale endowment model), leading to a rapid growth of the industry 2000 The poor equity market performance fuels hedge fund demand 2008 About 10,000 hedge funds with more than $2 Trillion in AUM, constituting more than half the trading volume on several major exchanges 17 How Do You Beat the Market? ➢ Conceptually, how do you beat the market? ➢ How do you beat the market in practice? – What do great investors have in common? How Do You Beat the Market? ➢ Categorization of hedge fund strategies (There is no standard, the various hedge fund index providers have different categories) Ainslie Chanos Asness Soros Harding Scholes Griffin Paulson Hedge Fund Strategies: Equity Strategies ➢ Equity long/short – Discretionary trading – Fundamental analysis and catalysts – It’s easy to be a contrarian, except when it’s profitable. – Buy on rumors, sell on news. ➢ Dedicated short bias – Identifying frauds, forensic accounting – While equity long/short is more long than short, the reverse is true for short biased funds ➢ Equity market neutral – Quant – Value, momentum, pairs trading, statistical arbitrage, high frequency trading, index arbitrage – Have a rule. Always follow the rule, but know when to break it. 20 Hedge Fund Strategies: Macro Strategies ➢ Global macro – Carry trades, central bank watching, devaluation, thematic, yield curve, country selection – Soros: When you have tremendous conviction on a trade, you have to go for the jugular. It takes courage to be a pig. – Bulls get rich, bears get rich, but pigs get slaughtered. ➢ Managed futures – Trading in trends and countertrends – Equity, fixed-income, and commodity futures, currency forwards – The trend is your friend. – Show me the charts, I’ll tell you the news. – Cut losses and let your profits run. 21 Hedge Fund Strategies: Arbitrage Strategies ➢ Event driven – Merger arbitrage (risk arbitrage), distressed, carve outs, spinoffs, splitoffs, when-issued, IPOs, SEOs, other corporate events, special situations ➢ Convertible bond arbitrage – long converts, hedge with equity, credit, fixed income – Gamma, busted, high-money ➢ Fixed income arbitrage – swap spread, yield curve, butterfly, mortgage, CDS-bond basis, on-the-run/off-the-run – Keynes: The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent. 22 What do Great Investors Have in Common? Investment Styles INVESTMENT STYLES RETURN DRIVERS Ubiquitous methods used across trading strategies and asset classes The reason that these methods work in an efficiently inefficient market Value Investing Risk premia and overreaction Trend-Following Investing (momentum and time series momentum) Initial underreaction and delayed overreaction Liquidity Provision Liquidity risk premium Carry Trading Risk premiums and frictions Low-Risk Investing (betting against beta) Leverage constraints Quality Investing Slow adjustment 23 Understanding Hedge Funds: Objectives and Fees ➢ Objective: – To make money in any environment – Absolute return benchmark (cf. relative return) ➢ Fees – Management fees – Performance fees – Classic fee structure: two-and-twenty ➢ Other fee characteristics – Hurdle rate – High water mark 24 Understanding Hedge Funds: Fees ➢ Distribution of management and incentive fees. Fung-Hsieh Table 2 25 Understanding Hedge Funds: Performance ➢ Past returns have been reasonably good (esp. before fees) and diversifying ➢ Beware of biases: – Backfill bias – Survivorship bias ➢ And risks: – – – – – Negative skewness Excess kurtosis Low persistence, i.e. winners do not remain winners High attrition Liquidity risk 26 Understanding Hedge Funds: Performance ➢ Performance statistics, 1995–2003. Malkiel-Saha Table 1. 27 Understanding Hedge Funds: Backfill Bias in Returns ➢ Malkiel-Saha Table 2, 1994-2003. 28 Understanding Hedge Funds: Attrition ➢ Malkiel-Saha Table 7, 1994–2003 ➢ Of 331 HFs reporting in 1996, 58 were still in existence in 2004, i.e. 18%. 29 Performance of Active Investors ➢ “Old consensus” in the academic literature: – Active investors as represented by mutual funds have no skill: Jensen (1968), Fama (1970), Carhart (1997) ➢ “New consensus” in the academic literature – The average mutual fund underperforms slightly after fees, not before fees, but the average hides significant cross-sectional variation across good/bad managers – Skill exists among mutual funds and can be predicted: Kacperczyk, Sialm, and Zheng (2008), Fama and French (2010), Kosowski, Timmermann, Wermers, White (2006): “we find that a sizable minority of managers pick stocks well enough to more than cover their Moreover, the superior alphas of these managers persist” – costs. Skill exists among hedge funds: Fung, Hsieh, Naik, and Ramadorai (2008), Jagannathan, Malakhov, and Novikov (2010), Kosowski, Naik, and Teo (2007): “top hedge fund performance cannot be explained by luck, and hedge fund performance persists at annual horizons… Our results are robust and relevant to investors as they are neither confined to small funds, nor driven by incubation bias, backfill bias, or serial correlation.” – Skill exists in private equity and VC: Kaplan and Schoar (2005) “we document substantial persistence in LBO and VC fund performance” ➢ Consistent with efficiently inefficient markets – For details see “Efficiently Inefficient Markets for Assets and Asset Management,” Garleanu and Pedersen (2015) Understanding Hedge Funds: Organization and the Master-Feeder Structure 31 Understanding Hedge Funds: Role in the Economy ➢ Hedge funds are useful: ➢ Make markets more efficient – – – – Collect information Trading impounds information into prices Monitors managers of companies This could improve real outcomes, e.g., • CEO decisions • real investment • capital allocation ➢ Provide liquidity – To investors who need to buy or sell (consumption smoothing) – To investors who need to hedge – To companies who need to issue securities ➢ Provide insurance against event risk to other investors 32