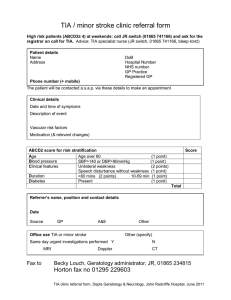

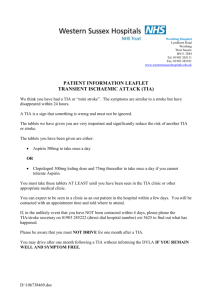

CONTINUED PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Dr Peter du Toit Travelling Fleet Supervisor – Medical Services Cell:: +39 3490875696 Email: peter.dutoit@msccruisesonboard.com NEUROLOGICAL EMERGENCIES PART 1- Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) The upcoming series of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) topics will center on neurological emergencies. The primary focus of the initial topic will be the effective management of patients exhibiting symptoms suggestive of a potential Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA). It is of utmost importance to approach ischemic strokes and TIAs with a perspective similar to that applied in cases of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS), drawing parallels between a TIA and Unstable Angina (UA), and likening an ischemic stroke to a ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). Statistics indicate that 10-15% of individuals who undergo a TIA subsequently experience a stroke within three months, with half of these incidents occurring within the first 48 hours. Rather than regarding TIAs as mere "mini-strokes," it is crucial to perceive them as forewarnings of an impending stroke—essentially high-risk events. Treating a TIA as neurological emergency delivers a level of care and urgency equivalent to that employed in managing ACS. There are many guidelines that describe the management of TIA’s similar to a minor ischemic stroke or non-disabling stroke. For our purposes, we are only going to focus on a patient that has had a neurological incident and has FULL resolution of symptoms. Please allocate sufficient time to review the articles and engage with the educational videos. Developing a comprehensive understanding of the management and risk stratification of high-risk neurological cases is essential. I have chosen the following references: 1. Diagnosis, Workup, Risk Reduction of Transient Ischemic Attack in the Emergency Department Setting: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association | Stroke (ahajournals.org) https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STR.0000000000000418 2. UPTODATE: Differential diagnosis of transient ischemic attack and acute stroke Differential diagnosis of transient ischemic attack and acute stroke - UpToDate 3. UPTODATE: The detailed neurologic examination in adults The detailed neurologic examination in adults - UpToDate 4. UPTODATE: Initial evaluation and management of transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke Initial evaluation and management of transient ischemic attack and minor ischemic stroke - UpToDate Certain passages and algorithms in the reference material will be highlighted in blue and author comments in gray. ** The attached UPTODATE articles are the main source of reference for this CPD** **Please allow your Team access to these articles** 1 DIAGNOSIS, WORKUP, RISK REDUCTION OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK IN THE ED SETTING (AHA) INTRODUCTION • Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is clinically described as an acute onset of focal neurological symptoms followed by complete resolution. • TIA has been recognized as a risk factor for future stroke since the 1950s. • Use of a time-based versus tissue-based definition for TIA has been debated since the 1980s and intensified with the widespread availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). • In 2009, the American Heart Association redefined TIA using a tissue-based approach (ie, symptom resolution plus absence of infarction on brain imaging) rather than the time-based approach (ie, symptom resolution within 24 hours alone). • TIA is now widely understood to be an acute neurovascular syndrome attributable to a vascular territory that rapidly resolves, leaving no evidence of tissue infarction on diffusionweighted imaging (DWI) MRI. • A patient with resolved symptoms and MRI demonstrating infarct should be diagnosed with an ischemic stroke EPIDEMIOLOGY • The true incidence of TIA in the United States is difficult to determine given its transitory nature and the lack of standardized national surveillance systems. • In addition, lack of symptom recognition by the public suggests that many TIAs go undetected. • Estimates of 90-day stroke risk after TIA range from 10% to 18% and highlight the importance of rapid evaluation and initiation of secondary prevention strategies in the emergency department (ED). • In a large and nationally representative population-based study, Kleindorfer et al estimated an incidence of 240 000 TIAs in the United States in 2002. o TIA incidence increases with age, similar to incidence trends of cardiovascular disease and stroke. COMMENT: • There was a time when TIA’s were not seen as a neurological emergency and the initial management options involved scheduling outpatient appointments weeks later. • With a shift to a tissue-based definition, more patients started undergoing imaging studies. • Data from these studies uncovered something surprising; some patients, despite symptoms fully resolving within 24 hours, actually suffered an ischemic stroke, as demonstrated by an infarct on MRI. • This has led to a more aggressive timeline and guidelines suggesting imaging should be undertaken withing 24 hours of the first symptom. • Current Emergency Department protocols for TIA’s and strokes are much like ACS protocols, emphasizing timely diagnosis and treatment, with access to advanced imaging and procedural interventions. • Therefore, if a patient displays signs and symptoms of a possible TIA, in the back of your mind you need to start thinking of a referral ashore to an ED/Stroke centre. 2 DEFINITION, ETIOLOGY, AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK (UPTODATE) MECHANISMS AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS • A TIA should be considered a syndrome. The symptoms of a TIA depend in part upon the pathophysiologic subtype, which are divided into three main mechanisms: 1. Embolic TIA, which may be artery-to-artery, or due to a cardio-aortic, or unknown source 2. Lacunar or small penetrating vessel TIA 3. Large artery, low-flow TIA 1. EMBOLIC TIA • Embolic TIAs are characterized by discrete, usually single, more prolonged episodes of focal neurologic symptoms. The embolus may arise from a pathologic process in an artery, usually extracranial, from the heart (e.g., atrial fibrillation, left ventricular thrombus) or aorta. Diligent investigation for a potential embolic source is necessary in all cases of TIA. • Embolic TIAs may last hours rather than minutes (such as in low-flow TIAs). • Emboli are subject to natural thrombolysis and migration since they typically break off from fresh thrombus. They may produce transient ischemia, but an element of silent infarction remains. • Embolic TIAs are best divided into those in the anterior cerebral circulation (carotid, anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery territory) and those in the posterior cerebral circulation (vertebrobasilar, posterior cerebral artery territory). o Anterior circulation embolic TIAs ▪ Embolic TIAs in the anterior circulation may be large enough to occlude the middle cerebral artery stem, producing a contralateral hemiplegia secondary to ischemia in the deep white matter and basal ganglion/internal capsule lenticulostriate territory. In addition, they may produce cortical surface symptoms. These include aphasic and dysexecutive syndromes (decision making, etc.) in the dominant hemisphere and anosognosia or neglect in the nondominant hemisphere. ▪ Smaller emboli that occlude branches of the middle cerebral artery stem result in more focal symptoms, including hand alone or arm and hand numbness, weakness, and/or heaviness induced by ischemia to the frontal area of the contralateral frontal lobe motor system. ▪ Transient monocular visual loss often signifies atherothrombotic disease in the internal carotid artery proximal to the ophthalmic artery origin. o Posterior circulation embolic TIAs ▪ Posterior circulation territory embolic TIAs are generally produced by emboli arising from atherothrombotic disease at the origin or distal segment of one of the vertebral arteries or of the proximal basilar artery. ▪ Emboli can produce transient ataxia, dizziness, diplopia, dysarthria, quadrantanopsia, hemianopsia, numbness, crossed face and body numbness, and unilateral hearing loss. When the top of the basilar artery is embolized, sudden, overwhelming stupor or coma may ensue due to bilateral medial thalamic, subthalamus, and medial rostral midbrain reticular activating system ischemia. Emboli in the more distal branches of the posterior cerebral artery may result in a homonymous field defect or in memory loss (inferior medial temporal lobe ischemia). 3 2. LACUNAR OR SMALL VESSEL TIA • These small vessel TIAs cause symptoms similar to the lacunar strokes that are likely to follow. • Thus, face, arm, and leg weakness or numbness due to ischemia in the internal capsule, pons, or thalamus may occur, similar to the symptoms due to ischemia from embolism or large vessel atherothrombotic disease or dissection. 3. LOW-FLOW TIA • Large artery low-flow TIAs are often associated with a tightly stenotic atherosclerotic lesion at the internal carotid artery origin or in the intracranial portion of the internal carotid artery when collateral flow from the circle of Willis to the ipsilateral middle or anterior cerebral artery is impaired. • Any obstructive vascular process in the extracranial or intracranial arteries can cause a lowflow TIA syndrome if collateral flow to the potentially ischemic brain also is diminished. • Low-flow TIAs usually are brief (minutes) and often recurrent. They may occur as little as several times per year but typically occur more often (once per week or up to several times per day) o Anterior circulation low-flow TIAs ▪ Symptoms due to ischemia from these lesions often include weakness or numbness of the hand, arm, leg, face, tongue, and/or cheek. ▪ Recurrent aphasic syndromes appear when there is focal ischemia in the dominant hemisphere, and recurrent neglect occurs in the presence of focal ischemia in the nondominant hemisphere ischemia. ▪ Limb-shaking TIAs are a rare, but classic, hypoperfusion syndrome of repetitive jerking movements of the arm or leg due to a severe stenosis or occlusion of the contralateral internal carotid or middle cerebral artery. o Posterior circulation low-flow TIAs ▪ In contrast, recurrent symptoms are often not stereotyped when the stenotic lesion that obstructs flow involves the vertebrobasilar junction or the basilar artery. ▪ Nevertheless, certain generalizations about recurrent low-flow TIA symptoms in the posterior circulation can be made. • Obstructive lesions in the distal vertebral artery or at the vertebrobasilar junction usually cause dizziness that may or may not include spinning or vertigo. The patient may complain that the room is tilting or that the floor is coming up at them, rather than spinning dizziness. Patients may use the word dizziness to describe a myriad of symptoms, not necessarily spinning. Other symptoms can include numbness of one side of the body or face, dysarthria, or diplopia. • Ischemia in the pons from stenotic lesions in the proximal to mid-basilar artery can cause bilateral leg and arm weakness or numbness and a feeling of heaviness in addition to dizziness. • Ischemia in the territory of the top of the basilar artery or proximal posterior cerebral artery may present with overwhelming drowsiness, vertical diplopia, eyelid drooping, and an inability to look up. 4 COMMENT: • I apologize for the complexity of the preceding text, but I highlighted the passage from UpToDate for the following reasons: o It is crucial to use accurate terminology when describing neurological symptoms and signs in your clinical notes. ▪ If English is not your first language, as is the case for me, it is vital to chart and document your findings using the correct terminology. ▪ You can locate and print glossaries from the internet to assist you. • StrokeGlossary.pdf (umich.edu) • glossary1.pdf (stroke.org.uk) o Understanding the pathophysiology is significant as it enhances your comprehension of how a TIA is caused and aids in excluding TIA mimics. ▪ Low-flow TIA: Manifesting classic transient focal neurological symptoms, whether in the anterior or posterior circulation, these episodes are brief, often lasting only minutes, and tend to recur. ▪ Embolic TIA: Having a similar presentation to a thromboembolic ischemic stroke, this type is localized to a specific arterial territory rather than a general circulation. Typically lasting hours, it is less prone to recurrence. ▪ Lacunar or small penetrating vessel TIA: These events share similarities with lowflow TIAs. However, the transient and recurrent neurological symptoms align with lacunar stroke syndromes. o Understanding the factors behind TIA, such as emboli and vascular stenosis, underscores the significance of vascular imaging. DIAGNOSIS, WORKUP, RISK REDUCTION OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT SETTING (AHA) CLINICAL EVALUATION • Acute onset of focal neurological symptoms followed by complete resolution is suggestive of TIA. • Therefore, patients for whom TIA is being considered must have a neurological examination consistent with their baseline status. • Specific details of the history and presentation can help differentiate TIA from alternate diagnoses. • Nonspecific symptoms or examination findings (eg, isolated dizziness, confusion/lethargy/encephalopathy), focal symptoms with other features (eg, headache, seizure), or new radiological findings (eg, mass lesion) may suggest an alternate diagnosis or “mimic”. • In cases of diagnostic uncertainty, conventional wisdom suggests performing a neurovascular workup for suspected TIA to reduce the risk of a recurrent event, ideally with expedited neurological consultation. 5 COMMENT: • Individuals with a possible TIA may reach the medical center via two routes: 1. Telephonically ▪ Contacting the first responder by phone. ▪ Following guidelines from https://www.nice.org.uk/, the first responder should employ a validated tool such as FAST (Face Arm Speech Test) outside the hospital to screen individuals with a sudden onset of neurological symptoms for a diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack. ▪ The Face Arm Speech Test (FAST; the "T" serves as a reminder of the importance of time and the need to reach a hospital immediately) evaluates suspected stroke patients by examining them for facial weakness, arm weakness, and speech impairment. ▪ FAST is considered positive if at least one item is abnormal. ▪ It is crucial for first responders to recognize that even if the symptoms have resolved, these patients are deemed high risk and should be promptly assessed in the medical center by the duty doctor. 2. Presenting directly to the Medical Center ▪ This situation is quite common. ▪ Patients may describe experiencing a momentary episode or incident but currently feel well. ▪ Often, they are only seeking advice, and it may require some persuasion for these patients to agree to an evaluation by the duty doctor in the Medical Center. COMMENT: • It is essential that the assessment of a patient with neurological symptoms, includes a thorough neurologic examination. • In the initial assessment of patients where TIA is under consideration, one of our primary objectives should be to verify the complete resolution of their symptoms. • Therefore, a meticulous examination is necessary to ensure: o No ongoing neurological signs or symptoms are present. o No new neurological signs or symptoms have emerged. IF A PATIENT HAS ONGOING OR NEW SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS – EVEN IF THEY ARE IMPROVING, THEY NEED TO BE TREATED AS A STROKE/STROKE MIMIC. • • • It quickly becomes apparent when reviewing clinical notes whether a physician has conducted a thorough neurological examination. There is a distinction between conducting a quick SCREENING TEST during the initial patient evaluation and performing a DETAILED NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION once the patient has been admitted. I have highlighted the following UpToDate topics on examinations and recommend taking this opportunity to familiarize yourself with a comprehensive neurological examination: o The detailed neurologic examination in adults - UpToDate o Detailed neurologic assessment of infants and children - UpToDate 6 • There is a Neurological examination section in SeaCare. o Refrain from clicking the normal examination box unless you have completed all the examinations within that paragraph. o o Instead, complete each individual section. ▪ If there are additional findings not covered in SeaCare, you can always include free text in the COMMENTS and ADDITIONAL NOTES section. Here are some examples of charting a neurological examination: ▪ Cheat Sheet: Normal Physical Exam Template | ThriveAP ▪ Normal Adult Exam - Paragraph format COMMENT: • Diagnosing a patient with a suspected TIA on a cruise ship can be challenging, especially when dealing with a guest or crew who are currently symptom-free. • The consequences for both the guest and crew can be substantial: o Crew: ▪ Referral to shoreside for imaging and neurology consultation. ▪ Potential repatriation home with implications for future employment. o Guest: ▪ Referral to shoreside for imaging and neurology consultation. ▪ Sacrifice of a day ashore and extended waiting times for assessment ashore. ▪ Stress for the entire family and extended family if onboard. ▪ Potential premature end of the cruise with additional travel arrangements for the family and repatriation home. • Conducting a thorough history is therefore essential to rule out any mimics. • Language barriers. o Avoid "lost in translation" scenarios and the use of translators where possible to prevent misunderstandings. • In the upcoming section, we will delve deeply into distinguishing a TIA from other causes of transient neurological events. 7 INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND MINOR ISCHEMIC STROKE (UPTODATE) DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS • Several neurologic disorders give rise to transient focal neurologic symptoms, and these should be considered before establishing a diagnosis of TIA. In addition to TIAs, the most important and frequent causes of discrete self-limited attacks include: o Seizure o Migraine aura o Syncope • Less frequent causes include: o Peripheral vestibulopathy that causes transient episodic dizziness. o Pressure- or position-related peripheral nerve or nerve root compression that causes transient paresthesia and numbness. o Metabolic perturbations such as hypoglycemia and hepatic, renal, and pulmonary encephalopathies that can produce temporary aberrations in behavior and movement. o Transient global amnesia. o Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND ACUTE STROKE (UPTODATE) DISTINGUISHING TRANSIENT ATTACKS • History is important in distinguishing the various causes of transient attacks. Useful historical features include: 1. The focal or nonfocal nature of attacks 2. The nature of the symptoms and their progression 3. The duration and timing of symptoms 4. Associated symptoms during and after the attacks • Nature of symptoms 1. Symptoms can be categorized using Jacksonian terminology as either "positive" or "negative." ▪ Positive symptoms indicate active discharge from central nervous system neurons. Typical positive symptoms can be visual (eg, bright lines, shapes, objects), auditory (eg, tinnitus, noises, music), somatosensory (eg, burning, pain, paresthesia), or motor (eg, jerking or repetitive rhythmic movements). ▪ Negative symptoms indicate an absence or loss of function, such as loss of vision, hearing, feeling, or ability to move a part of the body. 2. Seizures and migraine auras characteristically (but not always) begin with positive symptoms, while TIAs invariably are characterized by negative symptoms. Seizures occasionally cause paralytic attacks but, on close observation, there are usually features of the history and physical examination that suggest the presence of a seizure disorder such as minor twitching of a finger or toe or a tingling sensation in the affected limb. 8 • Progression and course 1. The progression and course of the symptoms are also helpful in the differential diagnosis. ▪ Migraine aura often progresses slowly within one modality. As an example, scintillations or bright objects tend to move slowly across the visual field. Paresthesia may gradually progress from one finger to all the digits, to the wrist, forearm, shoulder, trunk, and then the face and leg. This progression normally occurs over minutes. After the positive symptoms move, they are often followed by loss of function. The moving train of visual scintillations may end in a scotoma or visual field defect. Similarly, as paresthesia travels centripetally, it may leave the initial areas of skin numb and devoid of feeling. ▪ Migrainous aura typically progresses from one modality to another; after the visual symptoms clear, paresthesia begins. When paresthesia clears, aphasia or other cortical function abnormalities may develop. 2. In contrast to migraine: ▪ Seizures usually consist of positive phenomena in one modality which progress very quickly over seconds. ▪ TIA symptoms are negative; when more than one modality or function is involved, all are affected at about the same time. ▪ Loss of consciousness is very common in seizures and syncope, which usually produce relatively stereotyped attacks; in comparison, loss of consciousness is rare in TIAs, and symptoms can be stereotyped or different in various TIAs. • Duration and tempo 1. The duration and tempo of attacks also are useful in predicting the cause: ▪ Migrainous auras characteristically last 20 to 30 minutes, although they may persist for hours. ▪ TIAs are usually fleeting, usually lasting less than one hour. ▪ Seizures last on average about 30 seconds to 3 minutes; some seizures, including absence attacks, atonic seizures and myoclonic jerks, are shorter in duration. ▪ Syncope collapse is very brief (seconds) unless the patient is sitting up or otherwise cannot obtain a supine position. 2. Seizures occur sporadically over years and sometimes appear in flurries. In comparison, TIAs usually cluster during a finite period and can occur as frequent "shotgun"-like attacks. Attacks that are scattered over many years are almost always either faints, migraines, or seizures; TIAs almost never continue over this time span. • Precipitating factors 1. Precipitants often give clues to the cause of attacks. ▪ Activation of seizures may occur in some patients after stroboscopic stimulation, hyperventilation, stopping antiseizure medications, fever, and alcohol or drug withdrawal. ▪ In some patients, TIAs occur when blood pressure is reduced, or upon sudden standing or bending. ▪ Dizziness and vertigo in patients with peripheral vestibulopathies are often triggered by sudden movements and positional changes. 9 2. The "classical" or "typical" presentation of vasovagal syncope refers to syncope triggered by emotional or orthostatic stress, painful or noxious stimuli, fear of bodily injury, prolonged standing, heat exposure, or after physical exertion. Vasovagal syncope commonly occurs for example when patients see blood, have or are about to have phlebotomy or other medical procedures, see an electric saw poised to remove a plaster cast on their arm or leg, after standing up for a long time in church, or when a dental drill is aimed directly at their open mouth by a dentist. Hypovolemia also frequently precipitates syncope. • Associated symptoms 1. Non-neurologic associated symptoms can be characteristic of certain disorders. Headache is common after migraine aura and following a seizure. Headache can also occur during a TIA, but rarely at the same time or directly after neurologic symptoms. 2. A bitten tongue, incontinence, and muscle aches are frequently associated with seizure. Vomiting is common after migraine and occasionally follows syncope but is rare after or during TIA and rare in relation to seizure. In the latter circumstance, vomiting may develop after the patient has lost consciousness; patients do not recall vomiting unless they see the vomitus when they awaken. Nausea and a need to urinate or defecate often precede or follow syncope; sweating and pallor are other common features of syncope. • Age and sex of patient 1. Demographic information may be helpful but there is substantial overlap. Seizures occur at any age, while TIAs are not very common in young individuals, particularly those who do not have prominent risk factors for vascular disease (eg, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, cardiac disease, sickle cell disease, etc). In otherwise healthy women who are pregnant, transient focal neurologic symptoms are often related to migraine with aura, and usually have a benign outcome. 2. Syncope has little predilection for age and is more common in women. 3. TIAs and strokes are somewhat more common in men, although after menopause the frequencies are nearly equal in the two sexes. 4. Seizures have no strong sex predilection. COMMENT: • When obtaining a history for a potential TIA, it is crucial to scrutinize for signs or symptoms that may suggest alternative causes of transient focal neurologic symptoms. • The most common alternatives include Seizure, Migraine aura, and Syncope. • An essential point to bear in mind is that TIA’s are consistently marked by negative symptoms. o Negative symptoms denote an absence or loss of function, such as loss of vision, hearing, sensation, or the ability to move a part of the body. o In contrast, seizures and migraine auras typically (though not always) commence with positive symptoms such as tonic-clonic muscle contractions. • In the process of history-taking, also assess historical features, including: o The focal or non-focal nature of attacks, the nature of symptoms and their progression, duration and timing of symptoms, and any associated symptoms during and after the attacks. 10 11 TIAS AND STROKES, STATE OF THE ART | THE EM BOOT CAMP COURSE (852) TIAs and Strokes, State of the Art | The EM Boot Camp Course - YouTube 12 COMMENT: • The majority of Emergency departments in the US and Europe have Stroke and TIA protocols/pathways. • Unfortunately, they are all based on the outcome of advanced imaging which cruise ships do not have access to. • Some examples of UK pathways: o Microsoft Word - TIA Guidelines - BCAP vers6 3 08 _2_.doc (ruh.nhs.uk) o NHS Southeast Coast Integrated Stroke Care Pathway Service Specification (england.nhs.uk) • In the US, successful ED TIA protocols include several components that may account for their effect: ▪ a clinical protocol enabling rapid identification and diagnosis, ▪ rapid access to diagnostic testing and advanced imaging, ▪ risk stratification criteria (eg, ABCD2 score), ▪ access to neurovascular expertise, ▪ implementation of appropriate secondary prevention interventions, ▪ access to a short-term follow-up clinic 13 DIAGNOSIS, WORKUP, RISK REDUCTION OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK IN THE ED SETTING (AHA) DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION • Brain Imaging o In the ED, the role of acute phase imaging is to rule out alternative diagnoses, aid in risk stratification, and identify potentially symptomatic lesions. o An initial non-contrast head computed tomography (NCCT) is part of many stroke/TIA protocols given its accessibility in the ED setting, and is a useful initial test to evaluate for subacute ischemia, hemorrhage, or mass lesion. o NCCT alone, however, has limited utility in patients whose symptoms have resolved. o Although its sensitivity to detect an acute infarct is low, it does have utility in ruling out TIA mimics. o Multimodal brain MRI is the preferred method to evaluate an acute ischemic infarct and ideally should be obtained within 24 hours of symptom onset. In most centers this will follow a NCCT. o Some centers might have rapid access to MRI in the ED. In cases where MRI with DWI (Diffusion Weighted Imagining) can be obtained without delay, NCCT can be safely avoided in a stable patient with completely resolved symptoms. o TIAs typically last minutes with a linear increase in the likelihood of infarction with increasing symptom duration. o MRI with DWI demonstrates lesions in ≈40% of patients presenting with TIA symptoms, and DWI positivity is associated with a >6-fold increased risk of recurrent stroke at 1 year. o If a DWI-positive lesion is identified, a diagnosis of ischemic stroke is typically made‚ followed by hospital admission. • Vascular Imaging o Evaluation of TIA requires adequate vascular imaging. o Noninvasive imaging to screen for carotid stenosis (or vertebral artery stenosis for patients with posterior circulation symptoms) should be a routine component of the acute phase imaging for patients with TIAs. o A primary goal of vascular imaging is to identify patients with high-grade cervical carotid stenosis who might be candidates for revascularization. • Laboratory and Cardiac Testing, Neurology Consultation o Point-of-care blood glucose testing should be performed for all patients with suspected TIA to rule out hypoglycemia, a known stroke mimic. o A complete blood count, chemistry panel, hemoglobin A1c, and lipid profile can help identify potential risk factors. o Patients >50 years of age with visual complaints may benefit from screening with erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein to assess for temporal arteritis. o Other workups, including for infectious or toxic/metabolic processes, could be performed if such diagnoses are suspected. o Troponin assays, electrocardiography and ECHO are warranted on all patients with TIA given the shared risk factors for myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, and to screen for AF. o Initial electrocardiography detects AF in up to 7% of patients with ischemic stroke and TIA, but longer cardiac monitoring results in higher detection rates, especially among patients with palpitations or structural heart disease. 14 COMMENT: • Reviewing the various pathways, it becomes obvious that we can only perform the very initial stages of the management of a suspected TIA patient onboard. • Therefore, your onboard TIA pathway will focus on the initial assessment, neurological examination, laboratory tests and ECG. • The aim is to rule out TIA mimics, rule out a Stroke and confirm your suspicion of a TIA. • Consider the following steps for our onboard TIA pathway: 1. STEP 1 INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING PATIENTS INTO THIS TIA GROUP Patient that presents with a history of a short neurological deficit with FULL resolution of symptoms 2. STEP 2 INITIAL ASSESSMENT (REVIEW AND CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING ACTIONS) ▪ ▪ Admit to the medical centre ICU for continuous monitoring, further investigations, and treatment considerations. ▪ Attach cardiac and pulse oximetry monitors. ▪ Observations: Continuous heart rhythm and pulse oximetry monitoring. ▪ Vitals: Blood pressure, Heart rate, Respiratory rate, Temperature and Neuro observations on admission, and then every 15 minutes for the first hour. ▪ Establish IV access. ▪ Oxygen: In patients who have an oxygen saturation of ≥94 percent and no signs of respiratory distress. DO NOT routinely treat with supplemental oxygen. ▪ Perform a focused history and examination to rule in TIA and rule out Mimics 3. STEP 3 CONSIDER THE FOLLOWING INVESTIGATIONS: ▪ Random blood glucose ▪ FBC, U&E, LFT Cholesterol, possibly CRP and Pregnancy test (if woman of childbearing age) ▪ Cardiac: Trop I, ECG 4. STEP 4 CONFIRM TIA AS PRESUMPTIVE DIAGNOSIS ▪ Preferable after 4 hours admission ▪ During the admission the patient should have been monitored for any further neurological or cardiac signs. ▪ By now you will have completed a detailed history, detailed neurological, examination and received all the lab and ECG results. ▪ With this information you either: • Confirm TIA as the presumptive diagnosis and continue with the TIA pathway. • Manage the TIA mimic accordingly. 5. STEP 5 MEDICATIONS TO CONSIDER ▪ Aspirin 6. STEP 6 RISK STRATIFICATION 7. STEP 7 DISPOSITION 8. STEP 8 DISEMBARKATION OPTIONS 15 • If the vessel is in port, then the TIA pathway can be expedited. o Remember, this is not a STROKE patient where time is more critical. o The patient in front of you currently has NO signs or symptoms. o Spend some time ensuring you have the right diagnosis. o If you are confident of your diagnosis and the patient has a high ABCD2 score or other high-risk factors, refer to patient to a Tertiary center via an ambulance. • We will now focus on Step 5 to 8 o STEP 5 MEDICATIONS TO CONSIDER o STEP 6 RISK STRATIFICATION o STEP 7 DISPOSITION o STEP 8 DISEMBARKATION OPTIONS TIAS AND STROKES, STATE OF THE ART | THE EM BOOT CAMP COURSE (852) TIAs and Strokes, State of the Art | The EM Boot Camp Course - YouTube TIA TREATMENT 16 COMMENT: • It is important to discuss the use of antiplatelet therapy. • There has always been a concern of potentially increasing the morbidity of a patient with an undiagnosed intracerebral hemorrhage by prescribing Aspirin. • However, the UK guidelines are very clear: 1. Offer aspirin (300 mg daily), unless contraindicated, to people who have had a suspected TIA (following complete resolution of symptoms), to be started immediately. 1. Recommendations | Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management | Guidance | NICE • According to: NG128 Evidence review A (aspirin) (nice.org.uk) • The committee agreed that once a diagnosis of TIA has been suspected by a healthcare professional, it should be safe to give aspirin without significantly increasing the risk of haemorrhage. • The committee discussed the potential risk of giving aspirin to people with suspected TIA who actually have undiagnosed intracerebral haemorrhage. • It was noted that the baseline risk of haemorrhage is greater with stroke than TIA, but even in mild stroke (The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] <3) the risk of haemorrhage is <5%, as discussed in the included study. • It was also recognised that intracerebral haemorrhage (including intracerebral haemorrhage or convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage) can cause transient focal neurological symptoms that can mimic TIA. • The suspected TIA group are likely to have a much lower risk of intracerebral haemorrhage than patients with minor stroke, and therefore aspirin is more likely to be safe. • The committee were also aware of some retrospective data suggesting that even when aspirin is given in cases of intracerebral haemorrhage, the clinical condition does not deteriorate. • Therefore, taking all of these factors into account the risk of haemorrhage was agreed to be low. • So, there are two possibilities regarding giving antiplatelets: 1. If in doubt, wait until after the CT scan to rule out an intracerebral hemorrhage. 2. Follow the NICE guidelines and prescribe Aspirin. • Consider the following option: 1. Confirm it is a SUSPECTED TIA 1. The patient should have NO RESIDUAL SYMPTOMS. 2. IF RESIDUAL SYMPTOMS: TREAT AS A STROKE AND NO ASPIRIN TO BE GIVEN 2. Vessel in port: 1. Rule out MIMICS 2. Refer to Stroke Centre/Emergency Department with neuro-imaging capabilities. 3. Consider omitting Aspirin 3. Vessel at sea or in port with no neuro-imaging capabilities: 1. Rule out MIMICS 2. Discuss options with your patient- advise giving Aspirin is low risk. 3. Patient consents: Prescribe 300mg oral Aspirin. 17 DIAGNOSIS, WORKUP, RISK REDUCTION OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK IN THE ED SETTING (AHA) RISK STRATIFICATION • The use of validated risk scores as risk stratification tools for suspected TIA have gained wider acceptance. • An ideal scale for stroke risk prediction after TIA is one that is easy to calculate, has high predictive value, can categorize patients into clinically distinct risk groups, has been validated, and has broad generalizability. • Several TIA risk stratification instruments are available to help predict the short-term stroke risk for individual patients and to guide disposition. • It is critical for physicians to be aware of the limitations of the various TIA risk-scoring systems, including accuracy (ie, not incorporating high-risk features such as carotid stenosis, recurrent TIA, or AF) and external validity. • The most widely used risk stratification tool is Age, Blood Pressure, Clinical Features, Duration, and Diabetes (ABCD2) score. It can be used to stratify patients into low, moderate, or high-risk groups on the basis of clinical features and medical history. • It is important, however, to note the limitations of the ABCD2 score. o First, it does not include symptoms that might suggest a “posterior circulation” process, such as dysmetria, ataxia, or homonymous hemianopia. o It also does not account for TIA mechanism or the presence of ipsilateral large artery stenosis on imaging, and therefore should be part of a more comprehensive assessment. 0-3 points: Low Risk 4-5 points: Moderate Risk 6-7 points: High Risk 2-Day Stroke Risk: 1.0% 2-Day Stroke Risk: 4.1% 2-Day Stroke Risk: 8.1% 7-Day Stroke Risk: 1.2% 7-Day Stroke Risk: 5.9% 7-Day Stroke Risk: 11.7% 90-Day Stroke Risk: 3.1% 90-Day Stroke Risk: 9.8% 90-Day Stroke Risk: 17.8% 18 COMMENT: • The ABCD2 score has many detractors and there are many guidelines that advise not to use it. • However, it remains part of many Emergency Department guidelines where they use the score to determine type of medication to use and whether the patient should be admitted to hospital. • The ABCD2, together with other risk factors for recurrent TIA/Stroke definitely has a place in our maritime setting. • As with ACS, risk stratification is an important element when dealing with acute patients in our remote setting. • The higher the risk the less we want these patients to remain onboard our vessels. • Risk stratification can also help in determining whether a vessel at sea needs to be diverted or sped up. DIAGNOSIS, WORKUP, RISK REDUCTION OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK IN THE ED SETTING (AHA) We suggest hospitalization for patients with a TIA within the past 72 hours if any of the following conditions are present: • High risk of early stroke after TIA as suggested by the table opposite. • Other risk factors: • The presence of acute infarction on DWI (Diffusion Weighted Imagining) • ABCD2 score ≥4 • Ipsilateral large vessel stenosis ≥50 percent • Recent TIA within the last month • Subacute stroke on CT • Acute cardiac process, such as arrhythmia, pathologic murmur, recent myocardial infarction • The presence of a known cardiac, arterial, or systemic etiology of brain ischemia that is amenable to treatment 19 INITIAL EVALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK AND MINOR ISCHEMIC STROKE (UPTODATE) HOSPITAL OR OUTPATIENT EVALUATION? • Whether hospitalization is required for TIA evaluation is not clear, but urgent assessment and management is essential regardless of inpatient or outpatient status. • The key guiding principle is that the incidence of a recurrent stroke is highest in the 48 hours following the TIA, and therefore the rapidity with which the evaluation is performed, and treatments initiated is more important than the physical location of where the evaluation takes place. • Outpatient evaluation can now occur in specialty-run TIA clinics and in emergency department-based observation units; in both settings, the evaluation begins immediately following a TIA diagnosis. • Possible advantages of hospitalization include facilitated early use of thrombolytic therapy, mechanical thrombectomy, and other medical management if symptoms recur, expedited TIA evaluation, and expedited institution of secondary prevention. 20 COMMENT: • Disposition of the patient depends on the locations of the vessel. 1. In Port ▪ Once you have ruled out TIA mimics, these patients should be medically disembarked and referred to a shoreside stroke/ED facility. ▪ If you are confident of your diagnosis, especially if the patient has a high ABCD2 score or other high-risk factors, refer the patient to a Tertiary center with imaging capabilities via an ambulance. ▪ If you are in a port without these facilities, then contact Med Ops to discuss. 2. At Sea ▪ Consider admitting all patients with a possible TIA to the medical center. ▪ It is important to monitor the patient while you are assessing the history and performing a thorough neurological examination. ▪ Further laboratory tests and ECG’s will help in determining your final diagnoses and risk stratification. ▪ Rule out the common mimics: • Seizure • Migraine aura • Syncope ▪ Once you have made the diagnosis of presumed TIA, these patients should remain in the medical center until they are medically disembarked at the next available port. ▪ Risk stratification should NOT be used to determine whether they are to be admitted as it is unreliable. ▪ Risk stratification together with the presence of other high-risk symptoms can be used to determine the need for speedier disembarkation. • Once patients are home, they will be assessed for secondary prevention which we will not highlight during this CPD. LESSONS LEARNED AND PITFALLS • In each CPD module we will discuss LESSONS LEARNED and highlight potential PITFALLS LESSONS LEARNED • An incidence was noted where a guest had collapsed to the floor after suddenly feeling unwell. A Mike Echo response was initiated, and the Medical Team arrived at the scene. The team checked Airway, Breathing and Circulation. The patient was rousable but sleepy and the Team decided to transport her back to the Medical Centre. • A blood glucose measurement was not considered by the Team at scene. • It is IMPERATIVE to exclude hypoglycaemia using a rapid finger-prick bedside testing method when dealing with ANY collapsed patient, or patient presenting with neurological signs and symptoms. 21 The ABCDE Approach | Resuscitation Council UK • DISABILITY (D) o Common causes of unconsciousness include profound hypoxia, hypercapnia, cerebral hypoperfusion, or the recent administration of sedatives or analgesic drugs. o Review and treat the ABCs: exclude or treat hypoxia and hypotension. o Examine the pupils (size, equality, and reaction to light). o Make a rapid initial assessment of the patient’s conscious level using the AVPU method: Alert, responds to Vocal stimuli, responds to Painful stimuli or Unresponsive to all stimuli. Alternatively, use the Glasgow Coma Scale score. Painful stimulus can be given by applying supra-orbital pressure (at the supraorbital notch). o Measure the blood glucose to exclude hypoglycaemia using a rapid finger-prick bedside testing method. In a peri-arrest patient use a venous or arterial blood sample for glucose measurement as finger prick sample glucose measurements can be unreliable in sick patients. o Nurse unconscious patients in the lateral position if their airway is not protected. PITFALLS: • Beware TIA mimics especially Seizure, Migraine aura, and Syncope. FINAL COMMENT: • • • • • • • A Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) is clinically characterized by the sudden onset of focal neurological symptoms followed by complete resolution. o If ongoing symptoms persist, it indicates a stroke or stroke mimic, and requires appropriate management. TIAs should be treated as neurological emergencies. Statistics reveal that 10-15% of individuals experiencing a TIA go on to have a stroke within three months, with half of these incidents occurring within the first 48 hours. First responders should utilize FAST (Face Arm Speech Test) to screen individuals with a sudden onset of neurological symptoms. Caution should be exercised in swiftly diagnosing a patient with a presumed TIA. o Conduct a careful history to scrutinize for signs or symptoms suggesting alternative causes of transient focal neurologic symptoms. o In the process of history-taking, also evaluate historical features, including: ▪ The focal or non-focal nature of attacks, the characteristics of symptoms and their progression, duration and timing of symptoms, and any associated symptoms during and after the attacks. ▪ TIAs are consistently marked by negative symptoms. Aspirin is considered safe for a TIA patient with full resolution of symptoms, however, consider omitting it if you are in port and able to refer the patient for imaging. Patients diagnosed with a presumed TIA (after a thorough history, examination, labs, and monitoring) require specialist imaging and should, therefore, be medically disembarked. WHEN IN DOUBT, ERR ON THE SIDE OF CAUTION 22