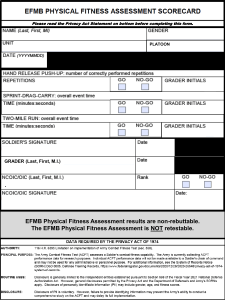

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283294101 Executive Summary From the National Strength and Conditioning Association's Second Blue Ribbon Panel on Military Physical Readiness: Military Physical Performance Testing Article in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research · October 2015 DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001037 CITATIONS READS 74 2,327 9 authors, including: Bradley Nindl Brent A Alvar University of Pittsburgh Point Loma Nazarene University 422 PUBLICATIONS 11,435 CITATIONS 76 PUBLICATIONS 7,020 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Michael Favre William J Kraemer University of Michigan The Ohio State University 10 PUBLICATIONS 360 CITATIONS 1,027 PUBLICATIONS 65,834 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: PhD thesis (Sport Coaching and Fitness Testing) View project Neuromuscular, cardiospiratory, endocrine, time of day and health responses and adaptations to resistance training and different combined endurance and strength training modes in men and women and athletes View project All content following this page was uploaded by Michael Favre on 10 October 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FROM THE NATIONAL STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING ASSOCIATION’S SECOND BLUE RIBBON PANEL ON MILITARY PHYSICAL READINESS: MILITARY PHYSICAL PERFORMANCE TESTING BRADLEY C. NINDL,1,2 BRENT A. ALVAR,3 JASON R. DUDLEY,4 MIKE W. FAVRE,5 GERARD J. MARTIN,6 MARILYN A. SHARP,7 BRAD J. WARR,7 MARK D. STEPHENSON,8 WILLIAM J. KRAEMER9 AND 1 Neuromuscular Research Laboratory/Warrior Human Performance Research Center, Department of Sports Medicine and Nutrition, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 2U.S. Army Public Health Center (Provisional), Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland; 3Rocky Mountain University of Health Professions, Provo, Utah; 4Department of Athletics, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Washington; 5Department of Athletics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; 6Department of Athletics, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut; 7Military Performance Division, U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, Massachusetts; 8Naval Special Warfare Human Performance Program, Virginia Beach, Virginia; and 9Department of Human Sciences, College of Education and Human Ecology, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio ABSTRACT Nindl, BC, Alvar, BA, Dudley, JR, Favre, MW, Martin, GJ, Sharp, MA, Warr, BJ, Stephenson, MD, and Kraemer, WJ. Executive summary from the National Strength and Conditioning Association’s second Blue Ribbon Panel on military physical readiness: Military physical performance testing. J Strength Cond Res 29(11S): S216–S220, 2015—The National Strength and Conditioning Association’s tactical strength and conditioning program sponsored the second Blue Ribbon Panel on military physical readiness: military physical performance testing, April 18–19, 2013, Norfolk, VA. This meeting brought together a total of 20 subject matter experts (SMEs) from the U.S. Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and academia representing practitioners, operators, researchers, and policy advisors to discuss the current state of physical performance testing across the Armed Services. The SME panel initially rated 9 common military tasks (jumping over obstacles, moving with agility, carrying heavy loads, dragging heavy loads, running long distances, moving quickly over short distances, climbing over obstacles, lifting heavy objects, loading equipment) by the degree to which health-related fitness compoDisclaimer: The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy, or decision unless so designated by official documentation. Address correspondence to Dr. Bradley C. Nindl, Bradley.c.nindl.civ@ mail.mil. 29(11S)/S216–S220 Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Ó 2015 National Strength and Conditioning Association S216 the nents (e.g., aerobic fitness, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and body composition) and skill-related fitness components (e.g., muscular power, agility, balance, coordination, speed, and reaction time) were required to accomplish these tasks. A scale from 1 to 10 (10 being highest) was used. Muscular strength, power, and endurance received the highest rating scores. Panel consensus concluded that (a) selected fitness components (particularly for skill-related fitness components) are currently not being assessed by the military; (b) field-expedient options to measure both health-based and skill-based fitness components are currently available; and (c) 95% of the panel concurred that all services should consider a tier II test focused on both health-related and skill-related fitness components based on occupational, functional, and tactical military performance requirements. KEY WORDS tactical training, military fitness, field-expedient testing H igh levels of physical fitness are essential for tactical athletes who engage in physically demanding occupations. Such occupations require high levels across a wide spectrum of health-related (muscular strength, muscular endurance, aerobic fitness, body composition, and flexibility) and skillrelated (agility, balance, coordination, power, reaction time, and speed) components of physical fitness (Table 1) (6,10,11). A physically ready and resilient military is essential for national security, and the military places a premium on TM Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. the TM Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research | www.nsca.com TABLE 1. Components and definition of physical fitness. Component Health-related components of physical fitness Muscular strength Muscular endurance Aerobic fitness Flexibility Body composition Skill-related components of physical fitness Agility Balance/dynamic balance Coordination Power Reaction time Speed Definition The ability of a muscle to exert a maximal force through a given range of motion or at a single given point The capacity of a muscle to repeatedly exert a submaximal force through a given range of motion or at a single point over a given time The ability of the cardiovascular system to continue training (working) for extended periods of time (periods longer than 20 min on average) The ability of a joint to move through a full range of motion The ratio of lean body mass to fat mass, or body mass to height The ability to rapidly and accurately change the direction of the whole body in space The ability to maintain equilibrium while stationary or moving The ability to use one’s senses and body parts to perform motor tasks smoothly and accurately The amount of force a muscle can exert as quickly as possible (force or strength per unit of time) The ability to respond quickly to stimuli The amount of time it takes the body to perform specific tasks (distance per unit of time) physical fitness training and testing (11,13,14). All combatoriented branches of the military (i.e., Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force) require regular fitness testing for their service members (Table 2) (2–5,12). Mandated physical fitness testing provides military leaders and commanders with useful information on assessing physical fitness levels, determining effectiveness of training regimens, identifying individual soldier strengths and weaknesses, and providing motivation to maintain individual physical readiness and preparedness (8,9). In general, although these military physical tests are conducive to testing a large number of soldiers, require no or minimal equipment, and are reliable and valid, they are limited regarding assessment across the spectrum of physical fitness components (8,9). These field-expedient physical fitness tests emphasize muscular endurance and aerobic fitness. These tests have been critiqued as having limitations in assessing “combat-fitness” (i.e., operationally defined in this article as the ability to successfully accomplish one’s military job, tasks, or duties) (1,6). As an example, the Marine Corps Combat Fitness Test, which consists of an obstacle course-like test, would appear to have advantages over traditional, military physical fitness tests, in that it requires abilities across a spectrum of both healthand skill-related physical fitness components (12). Currently, the Army, Air Force, and Navy have study projects in which they are also considering additional tests (i.e., tier II specialized tests based on occupational and functional requirements that go beyond the scope of standard physical fitness tests such as push-ups, sit-ups, and running) which may provide greater insight into soldier physical and combat fitness abilities. Recognizing a need to foster dialogue on the state-of-thescience for military physical performance testing, the National Strength and Conditioning Association’s (NSCA) tactical strength and conditioning (TSAC) program sponsored and hosted the second Blue Ribbon Panel on military physical readiness: military physical performance testing immediately after the NSCA’s fourth annual TSAC conference on April 18–19, 2013 in Norfolk, VA. The second Blue Ribbon Panel was convened to continue the TSAC program’s commitment to its mission of providing state-of the-art physical training and education and to expand and deliver this information to those who serve and protect our country and communities. This meeting brought together a total of 20 subject matter experts (SMEs) from the U.S. Army, U.S. Marines, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, and academia representing practitioners, operators, researchers, and policy advisors to discuss the current state of physical performance testing across the Armed Services. The SME panel initially rated 9 common military tasks (Table 3) by the degree to which health-related fitness components (e.g., aerobic fitness, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and body composition) and skillrelated fitness components (e.g., muscular power, agility, balance, coordination, speed, and reaction time) were required to accomplish these tasks. A scale from 1 to 10 (10 being highest) was used. These results are shown in Table 3. VOLUME 29 | NUMBER 11 | SUPPLEMENT TO NOVEMBER 2015 | S217 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Military Fitness Testing TABLE 2. Physical fitness tests of the U.S. military services. Service Guidance/doctrine manual Army Navy Marines Air Force Test Army physical readiness training Army physical fitness test: a 3-test event: (TC 3-22.20, 2010) (4) maximum number of push-ups in 2 min; maximum number of sit-ups in 2 min; the fastest time to complete 2 miles Navy physical readiness test: a 3-test event: Navy physical readiness maximum number of sit-ups in 2 min; program (OPNAVINST maximum number of curl-ups in 2 min; the 6110.1H, 2005) (5) fastest time to complete 1.5 miles Marine Corps physical fitness test: maximum Marine Corps physical fitness number of pull-ups (men); maximum time for program (MCO 6100.13, flexed arm hang (women); maximum number 2008) (12) of crunches in 2 min; the fastest time to complete 3 miles Marine Corps combat fitness test: an obstacle course test consisting of a sprint timed for 880 yards, lift a 30-pound ammunition can overhead from shoulder height repeatedly for 2 min, and perform a maneuver-under-fire event, which is a timed 300-yard shuttle run Air Force physical fitness test: a 4-event test: Air Force guidance maximum number of push-ups in 1 min; memorandum on fitness maximum number of sit-ups in 1 min; the program (AFI 36–2905, fastest time to complete 1.5 miles; abdominal 2010) (3) circumference Fitness components tested Muscular endurance, aerobic fitness Muscular endurance, aerobic fitness Muscular strength,* muscular endurance, aerobic fitness Agility, balance speed, coordination Muscular endurance, aerobic fitness, body composition† *Many subject matter experts consider the pull-up test to be a test of muscular endurance. †All services assess body composition as a component of physical fitness. Muscular strength, power, and endurance received the highest rating scores. The Blue Ribbon Panel then broke into SME groups to establish a list of field-expedient tests that could be considered for military physical performance testing for later voting by the entire panel. The 20 SMEs were divided into 4 groups to identify a list of field-expedient testing options for the fitness components: group A (muscular endurance, cardiovascular endurance, and body composition), group B (muscular strength and power), group C (speed, agility, and reaction time), and group D (flexibility, balance, and coordination) (1,7). From the lists of field-expedient tests that each group generated, the entire panel then voted to prioritize these tests. Table 4 lists the field-expedient tests that received the most votes by the panel. Panel discussion centered on whether the services should have a common-criteria healthbased fitness test (82% of panel members concurred) and whether services should consider a tier II test focused on both health-related and skill-related fitness components based on occupational, functional, and tactical military performance requirements (95% of panel members concurred). It was noted that the Marine Corps currently has a combatoriented functional fitness test; however, none of the services currently have an occupationally-specific physical fitness S218 the assessment. The Army, Air Force, and Navy have study initiatives considering tier II fitness tests. Subsequently, the panel discussed the need to consider whether Department of Defense (DoD) Instruction 1308.3, “DoD Physical Fitness and Body Fat Programs Procedures” (2), should be revised to consider inclusion of tier II tests to assess functional and skillrelated fitness components related to occupational tasks. The most valued resource in the U.S. military is the individual service member. The human dimension strategy of the U.S. military places a premium on optimizing the physical, cognitive, and social aspects of soldiering. In an era of fiscal austerity and military downsizing, innovative and transformative efforts are required to optimally develop and train the military’s physical readiness. Over the past decade of conflict, the physical readiness has been universally recognized as a force multiplier for combat effectiveness, resilience, and survivability on the battlefield. The military spends billions of dollars each year developing and producing tactical weapons and funding the associated training necessary to deploy them. The financial commitment to training and testing physical readiness is pale in comparison. As the military moves forward to a smaller, lighter, more mobile force in the fight against the global war on terrorism, a long-term comprehensive commitment to the highest TM Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. the TM | www.nsca.com 5.7 6.5 2.2 2.7 4.0 9.3 2.6 4.1 5.5 5.2 9.9 4.0 2.2 1.6 2.2 3.0 Fitness component Aerobic fitness 4.1 2.3 2.6 4.4 Speed 4.0 6.6 1.6 1.6 1.4 6.0 TABLE 4. Field-expedient options for assessing fitness components as identified by the SMEs.* Aerobic fitness 3.9 3.0 3.6 4.6 Muscular endurance *SME = subject matter expert. †A scale from 1 to 10 was used to rate how each health- or skill-related fitness component contributed to completing military tasks. zBold values are those rated by SMEs as .7.0 for essential capacity needed to accomplish the task. 5.9 5.0 4.9 4.7 6.0 2.7 3.4 5.0 6.1 5.1 5.3 5.5 6.5 7.7 6.0 6.6 8.3 9.7 7.7 7.3 5.7 5.4 6.3 6.0 6.7 5.5 5.0 5.9 7.0 4.8 5.7 5.8 6.5 9.8 2.9 3.3 3.0 7.8 9.0 5.4 6.2 7.4 3.1 7.8 7.5 4.7 8.8 9.2 3.8 6.0 4.0 5.5 7.5 7.4 6.9 5.0 6.4 5.8 5.2 5.2 6.9 6.2 6.9 9.5 3.7 4.5 3.2 7.0 5.7 8.4 5.0 4.8 3.2 6.4 5.9 6.1 3.3 3.8 3.2 4.4 Muscular strength Jump or leap over obstacles Move with agility-coordination Carry heavy loads Drag heavy loads Run long distances Move quickly for short distances Climb over obstacles Lift heavy objects off ground Load/stow/mount hardware Overall mean Coordination Balance Agility Flexibility Body composition Strength Power Endurance Military tasks TABLE 3. SME ratings for the degree to which health- and skill-related fitness components were required to accomplish common military tasks.*†z Reaction time Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Flexibility Body composition Speed Agility Power Coordination Balance Reaction time Field-expedient options Running test (1–3 miles) Beep test Isometric dynamometer Pull-up† Incremental dynamic lift Push-up Push-ups Burpee (squat thrust) Squat Functional movement screen Sit and reach Y-balance Circumference measurements A 40-yard sprint A 300-yard shuttle run T-test agility drill Standing broad jump Vertical jump Medicine ball throw Sit-up and stand without using hands Burpees Beam walk Y-balance NA *SME = subject matter expert; NA = not applicable. †Many SMEs consider the pull-up test to be a test of muscular endurance. quality physical readiness training is mandatory to ensure our future success. The following conclusions were drawn from the NSCA’s second Blue Ribbon Panel of military physical readiness: (a) selected fitness components (particularly for skill-related fitness components) are currently not being assessed by the military; (b) field-expedient options to measure both healthbased and skill-based fitness components are currently available; (c) military branches may want to consider having common health-related fitness-based tests. Concern for historical perspective and appropriate health-based criterion reference standards should be given to alter military physical performance testing if needed; and (e) it seems prudent for each branch of the military to design an occupational, functional, and tactical military performance test for inclusion as part of a fitness testing battery. REFERENCES 1. Caspersen, CJ, Powell, KE, and Christenson, GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 100: 126–131, 1985. VOLUME 29 | NUMBER 11 | SUPPLEMENT TO NOVEMBER 2015 | S219 Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Military Fitness Testing 2. Department of Defense. DoD Physical Fitness and Body Fat Programs Procedures. Washington, DC: DoD Instruction 1308.3, 2002. 3. Department of the Air Force. Air Force Guidance Memorandum on Fitness Program. AFI 36-2905, 2010. 4. Department of the Army. Army Physical Readiness Training. TC 3-22.20, 2010. 5. Department of the Navy. Navy Physical Readiness Program. OPNAVINST 6110.1H, 2005. 6. Epstein, Y, Yanovich, R, Moran, DS, and Heled, Y. Physiological employment standards IV: Integration of women in combat units physiological and medical considerations. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2673–2690, 2013. 7. Hogan, J. Structure of physical performance in occupational tasks. J Appl Psychol 76: 495–507, 1991. women’s strength/power and occupational performances. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 1011–1025, 2001. 10. Nindl, BC, Castellani, JW, Warr, BJ, Sharp, MA, Henning, PC, Spiering, BA, and Scofield, DE. Physiological employment standards III: Physiological challenges and consequences encountered during international military deployments. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2655–2672, 2013. 11. Nindl, BC, Williams, TJ, Deuster, PA, Butler, NL, and Jones, BH. Strategies for optimizing military physical readiness and preventing musculoskeletal injuries in the 21st century. US Army Med Dep J Oct-Dec: 5–23, 2013. 12. United States Marine Corps. Marine Corps Physical Fitness Program. MCO 6100.13, 2008. 8. Knapik, JJ and Sharp, MA. Task-specific and generalized physical training for improving manual-material handling capability. Int J Ind Ergon 22: 149–160, 1998. 13. Warr, BJ, Alvar, BA, Dodd, DJ, Heumann, KJ, Mitros, MR, Keating, CJ, and Swan, PD. How do they compare?: An assessment of predeployment fitness in the Arizona National Guard. J Strength Cond Res 25: 2955–2962, 2011. 9. Kraemer, WJ, Mazzetti, SA, Nindl, BC, Gotshalk, LA, Volek, JS, Bush, JA, Marx, JO, Dohi, K, Gomez, AL, Miles, M, Fleck, SJ, Newton, RU, and Hakkinen, K. Effect of resistance training on 14. Warr, BJ, Scofield, DE, Spiering, BA, and Alvar, BA. Influence of training frequency on fitness levels and perceived health status in deployed National Guard soldiers. J Strength Cond Res 27: 315–322, 2013. S220 the TM Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research Copyright © National Strength and Conditioning Association Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. View publication stats