Education Management & Leadership: South African Perspective

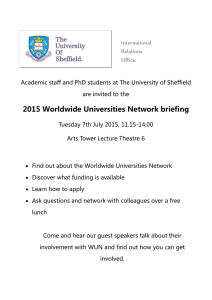

advertisement