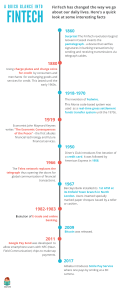

Administrative Science Quarterly 2022, Vol. 67(4)NP65–NP68 Ó The Author(s) 2022 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/00018392221119293 journals.sagepub.com/home/asq Eswar S. Prasad. The Future of Money: How the Digital Revolution Is Transforming Currencies and Finance. Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021. 496 pp. $35, hardcover. The Future of Money considers the likelihood that various digital currency projects will succeed in the medium and long terms and that we will have true digital money (explained below), perhaps even truly global digital money. While written from the perspective of a central bank economist, the book is highly readable and accessible to those without formal training in monetary economics and policy. As it describes projects likely to become reality over the next five to ten years, The Future of Money is relevant for social science scholars interested in technology, digitalization, markets, and organizations. The book is structured in four sections (Laying the Bedrock, Innovations, Central Bank Money, Ramifications) and ten chapters. It opens with a short introduction to money and finance, after which it delves into financial technology (fintech), considered by many to be both a disruptor of established financial institutions (especially retail banks) and a prefiguration of future financial services. Fintech is actually an umbrella term that includes various types of financial services related to retail banking, cross-border payments, insurance, crowdfunding, asset trading and investments, or credit rating (to name but a few). At a basic level, these services have in common the uses of various algorithmic models and software codes as a substitute for human labor and expertise in the services’ provision. The Future of Money is largely a global survey of developments in fintech, with a focus on money and payments (both intra- and cross-border) rather than being anchored in original empirical research. The fact that it has a global outlook is one of its strengths, as so many developments in fintech have occurred outside the United States. Eswar Prasad gathers data from third parties and does not offer his own in-depth analyses, which left this reader with a sense of potential unexplored depths. Also, the focus is on financial institutions rather than the technologies underpinning them. Readers get the usual explanations of how a blockchain network works and how blocks are generated, but no deeper sense of the on-the-ground technological setup (e.g., server farms, hardware, networks) required by distributed ledger technologies (DLTs). Section II, Innovations, opens with an overview of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, contrasting the utopian project with the reality on the ground. The text reveals, however, that Prasad, while trying to maintain an objective tone, is no crypto enthusiast. When it comes to whether fintech could make the world a better place (in the context of this book, better means mostly more efficient, less costly), Prasad’s answer is ‘‘yes’’ but with some hesitations and qualifications. Yes, fintech has the potential to make the world a more efficient NP66 Administrative Science Quarterly 67 (2022) place, but the same cannot be said of blockchain and Bitcoin. (Ethereum is skimmed over and other blockchain projects barely mentioned.) The bulk of the book (and its major strength) is sections III and IV, about central banking and the prospects of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). CBDCs are digital currencies being run on DLTs (some of which, but not all, are blockchain-based), largely in permissioned networks. A CBDC is not the software inscription (or representation) of a (monetary) value. The code is the value. In Prasad’s perspective, fintech developments are only a prelude to CBDCs, and if there is any future for digital money, it lies with CBDCs. Prasad offers a clear exposition of central bank operations, the different money measures, the relationships between central banks and commercial ones, intermediation processes, and monetary policy instruments. Additionally, he offers a comprehensive review of the various CBDC projects (in different stages of development) run by central banks around the world, estimating their chances of becoming reality in the near and medium futures. (The most advanced of these projects is run by the People’s Bank of China, but the one run by Sweden’s Riksbank is also advanced.) He also examines various projects to make Bitcoin a means of payment (some run by developing countries such as El Salvador), with a thoroughly negative verdict. The Future of Money examines details of several versions of CBDCs, some of which could run between central banks and the banks holding deposits with them, some conceived as retail CBDCs (i.e., running directly between central banks and citizens), some double layered (i.e., central bank to banks is one layer and banks to consumers is another layer), and some conceived as a global digital currency of the central banks themselves (run through the International Monetary Fund, for instance). Prasad’s argument is that CBDCs will reduce the costs of central banking, making it easier to implement monetary policies (such as negative interest rates), and will simplify intermediation processes. In addition, for developing economies, CBDCs will facilitate the inclusion of informal economic processes in the formal economy. This is no small feat, as in some countries the informal economy contributes around 40–50 percent of the total economic output. When it comes to financial inclusion—that is, offering banking and financial services to disadvantaged socioeconomic groups—Prasad is moderately optimistic about the potential of CBDCs, noting that some countries (e.g., Kenya) have achieved this with existing digital technologies. The author is also moderately optimistic about CBDCs’ potential to eliminate the scope for criminal activities but decidedly more so about their potential to reduce corruption. Another big advantage of CBDCs would be casting light upon shadow banking (i.e., financial activities conducted by non-banking institutions) and improving the state’s tax collection. These are the major advantages, but there are disadvantages as well, some of which deserve serious discussion. To his credit, Prasad acknowledges these disadvantages: one is that the introduction of CBDCs would reduce the seigniorage revenues of central banks (these are relatively modest anyway). Other disadvantages could include social control (e.g., authorities deciding that digital money can be spent on some goods but not others) and lack of privacy. Book Review NP67 Yet another is that CBDCs could be set with different expiration dates—and thus endowed with different values, potentially leading to secondary markets arbitraging them. One aspect Prasad does not discuss at all is the infrastructural investments required by CBDC projects—the server farms, communication networks, and cybersecurity provisions (including national security considerations) necessary to implement and use CBDCs. It is not clear to this reader that CBDCs would require only minimal infrastructural investments. Another aspect is how they would impact the expertise of central bankers—it is hard to imagine that CBDCs would have no impact at all on skills, expertise, and the banking professions. A major potential disadvantage of CBDCs is the sovereign’s power vis-à-vis citizens’ rights. A sovereign who can restrict the use of money to particular categories of goods and services, who can reward so-called good citizens and punish bad ones by expanding or restricting the available goods and services, and who can set expiration dates on money raises serious political and social questions beyond the realm of central bank economics (Prasad acknowledges this). A model whereby central banks would use CBDCs only in their dealings with depositor institutions (i.e., other banks) raises questions, too, as these institutions would each be able to set up their own stablecoins tethered to the central bank’s CBDC, with the potential to create a captive environment for their customers. Another important aspect Prasad does not deal with but that lurks in the background is the impact of CBDCs on organizations. We should assume that the introduction of CDBCs will have a major impact on organizations large and small, not only because all organizations will have to update their accounting systems (a major hard- and software investment) but also because of the potential impact on cash flows, operations, and taxation, among other things. We can well imagine that the closer an organization is to financial markets, the larger the impact will be. Scholars of financialization have argued that financial operations have become more important as profit centers for organizations, while organizational roles such as chief risk officer and chief financial officer have become more widespread and important, too. We would expect that the impact of CBDCs will be directly proportional to the size and role of financial operations in a given organization. While not examining this impact directly, Prasad’s book should prompt debate about this issue among organizational scholars. A separate conversation will be necessary about the impact of blockchain technologies on organizations, as applications of the latter go well beyond CBDC projects. The Future of Money was published in 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when different degrees of travel restrictions were in force across the globe. Against the background of what appeared then to be a diminished global world, the book makes a plea for, if not a statement of, faith in continued globalization. CBDC projects can be interpreted through this lens, although Prasad notices that various countries (primarily Russia and China) have tried to set up transnational payment systems as alternatives to SWIFT, the dominant messaging system. If successful, CBDCs could potentially erode the dominance of SWIFT—if that happens, it will be in the long run, in Prasad’s view. We are thus NP68 Administrative Science Quarterly 67 (2022) ultimately presented with a still-uncertain future: if CBDCs succeed, and depending on the form in which this would happen, the future of money will be digital (with cash surviving at the margins, at least for a while) but not necessarily global or reflecting a global currency. Alex Preda King’s College London 30 Aldwych, London WC2B 4BG United Kingdom alexandru.preda@kcl.ac.uk