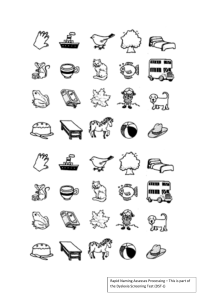

A SEND (Dyslexia) early-middle childhood - Part 1: Begin by presenting the chosen topic The chosen topic is SEND (Dyslexia) in early-middle childhood. This refers to special educational needs and disabilities that can affect a child's learning and socialization abilities (Government Digital Service, 2014). Dyslexia affects 10% of the population yet is little understood (British Dyslexia Association, n.d.). Dyslexia symptoms include delayed speech, difficulty pronouncing long words, problems with expression, lack of appreciation for rhyming words, little interest in learning letters, confusion with letter order, difficulty writing answers, slow writing speed, poor handwriting, and problems with copying written language (NHS, 2022). However, many dyslexics still excel in their reasoning and visual/creative skills (British Dyslexia Association, n.d). This is because it does not affect a child's sense of reasoning (NHS, 2022). To this end, Huang et al. (2020) found that children aged 7-12 with dyslexia in a community in China had low academic performance but still excelled in other areas. In support of this, The World Bank (2021) has emphasized the importance of not learning only academic skills but also cognitive, socio-emotional, technical, and digital skills for success in the labour market of the 21st century. One common way a child with dyslexia was spotted in the past was through poor academic performance, particularly in reading, compared to their peers of the same age. This means that diagnosis and intervention are often not initiated until a child is already struggling, which can impact the effectiveness of interventions and lead to emotional difficulties (Nielsen et al., 2018) and generalisations in educational provision. However, recent advancements have allowed for the early recognition of other signs that indicate a child may be at risk for dyslexia, even as early as in Kindergarten (Caglar-Ryeng, Eklund, & Nergård-Nilssen, 2019) such as the use of Computer adaptive testing. This early identification enables interventions to be implemented to prevent a downward spiral of underachievement, low self-esteem, and poor motivation. Dyslexia is a condition that experts are still unsure about the exact cause of because it is not solely a neurological condition Protopapas and Parrila, 2018) but can be present from birth (The British Psychology Society, 2018). However, it is often seen to run in families, suggesting a genetic component. Additionally, studies have found issues with how the brain connects letters and words with their corresponding sounds. It is important to note that dyslexia is not caused by poor vision and individuals with dyslexia do not see letters and words backward (International Dylexia Association, 2019). Macdonald et al. (2017) argue against the belief that seeing letters backwards is a common sign of dyslexia in the U.S. Dyslexia is a processing difference that impacts literacy, cognitive processes, and educational performance (Reid, 2016). In addition, it can affect individuals of all ages, genders, and intelligence levels (Reid, 2019). Therefore, individual differences, age and learning styles should be considered when planning interventions (Reid, 2019). To gain a better understanding of dyslexia in early-middle childhood, it is important to learn about developmental theories such as Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development suggests that children move through four different stages of learning which are the sensorimotor stage (Birth to 2 years), Preoperational stage (Ages 2 to 7), Concrete operational stage (Ages 7 to 11) and Formal operational stage (Ages 12 and up). His theory focuses not only on understanding how children acquire knowledge but also on understanding the nature of their intelligence (Hugar et al., 2017). Piaget believed that children take an active role in the learning process, acting much like little scientists as they perform experiments, make observations, and learn about the world. As kids interact with the world around them, they continually add new knowledge, build upon existing knowledge, and adapt previously held ideas to accommodate new information. The theory is further broken down into two stages by Al-Shidhani and Arora (2012) which are stage-independent conception and stagedependent conception. In the stage-independent conception, cognition and intelligence are independent of a particular stage of development. This stage involves processes such as assimilation and accommodation, where the child adjusts their cognitive structures to fit new stimuli. In the stage-dependent conception, there are four sub-stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational. Each sub-stage has its characteristics and challenges. Children with dyslexia may struggle with maintaining equilibrium between assimilation and accommodation, leading to difficulties with reading and writing. It is important to screen for dyslexia during the preschool years and conduct diagnostic tests to rule out other causes. Therefore, effective communication between healthcare workers, teachers, and parents, along with appropriate counselling is needed to enhance treatment practices and outcomes for children with dyslexia. The key argument around SEND (dyslexia) in early middle childhood is that some studies on learning disabilities in children with high intellectual potential (HIP) are underrepresented in the scientific literature, although their number has been increasing gradually over the years. Some studies claim that the prevalence of HIP among dyslexic readers is higher than the prevalence of HIP among normal readers. For instance, Toffalini et al. (2017) reported a proportion of 5.06% HIP children among dyslexic readers compared to 1.82% HIP children among normal readers. This proves that individuals with dyslexia could still maintain a high level of intelligence compared with normal individuals without dyslexia. Dyslexia is seen as part of a continuous range of reading abilities, although there is still debate about whether it is a separate condition. Research has not found a specific dyslexia gene, but there are multiple candidate genes implicated. Dyslexia can be disabling for some individuals, but it is not easily defined or consistent in its presentation. Some authors argue that it is not a useful concept, but the term is likely to remain in popular usage (Gibbs & Elliott, 2020). However, dyslexia is not a disability, but a learning difficulty. Some have succeeded in school, higher education and business. Indeed, they are well backed throughout by a support system. On the other hand, some were unable to complete their education due to their learning disability. Nevertheless, children's academic achievement should not be the sole measure of their success, as it is unfair to evaluate them based solely on this aspect. Nicolson and Fawcett (2019) argue that a positive dyslexia journey should involve positive assessment, aspirations, and acceleration, ultimately leading to a positive career. This responsibility falls not only on educators and schools but also on parents and the community. On the other hand, negative school experiences can have detrimental effects on children, leading to low self-esteem, anxiety, and emotional instability (Huang et al., 2020). Negative attitudes toward a student having a SEND (dyslexia) such as reprimands from teachers, rejection from peers, and emotional distress can worsen the condition. Due to their learning challenges, individuals are more likely to experience boredom in the classroom and lose interest in attending school. In addition, their academic performance will suffer, and they will be more susceptible to peer bullying. In some cases, children may seek adult friendships and engage in social issues outside of school as a coping mechanism (Huang et al., 2020). Additionally may exhibit aggression, anti-social behaviour, and hyperactivity (Sridevi et al., 2015). There are various educational interventions and programs available for children with dyslexia. These can range from regular teaching in small groups with a learning support assistant to oneon-one lessons with a specialist teacher. Phonics interventions, which focus on phonological skills, are commonly used for example to help them recognise that even short words such as "hat" are made up of 3 sounds: "h", "a" and "t" (NHS,2022). These interventions teach children to recognize and identify sounds in spoken words, combine letters to create words and monitor their understanding while reading. A research finding from Egypt has similarly shown that reading interventions enhance phonological awareness among at-risk kindergarten pupils (Elmonayer, 2013). In the Egyptian study, Elmonayer (2013) developed a Kindergarten Inventory of Phonological Awareness and administered pre-and post-tests to children in experimental and control groups. The researcher engaged the experimental group in reading activities designed to improve their phonological awareness skills, while the control group participated in regular classroom activities. The findings show that the children in the experimental group demonstrated higher levels of phonological awareness than those in the control group. Similarly, the intervention for children with dyslexia was evaluated using phoneme counting to assess phonological analysis skills by having children count the number of phonemes in a given logatome (Valdois et al., 2014). Ran colours were used to measure rapid automatized naming skills by having children name the colours on a board as quickly and accurately as possible (Harrar-Eskinazi et al., 2022). The study’s results in these aforementioned interventions suggest that phonological awareness intervention can effectively address deficits in phonological awareness and facilitate reading acquisition. At small group intervention levels, children may benefit from small group interventions that also include phonemic awareness and phonics instruction tailored to their needs as well as the possibility for more intense, one-on-one additional support for children reading well below grade level expectations or at higher risk for dyslexia. For example, studies have shown that implementing a Multi-tiered System of Support (MTSS) in kindergarten through third grade is effective and feasible (Wanzek et al., 2016). Specifically, children in second and third grades with severe reading deficits who received reading interventions experienced growth rates comparable to students without special education reading needs (Burns et al., 2020). Additionally, State policies and expert opinion generally favour schools’ use of a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS; Miciak & Fletcher, 2020). Within MTSS, children are screened early and at multiple time points to assess the risk for dyslexia. Scores that assess the risk of dyslexia are then used to make instructional decisions, such as the delivery of intensive intervention specially designed to address individual child needs. Within the home and community setting various supports exist to reinforce and augment the school interventions; however, the evidence basis for these supports is limited (e.g., Norwich et al., 2005; Regtvoort & van der Leij, 2007). University reading clinics and community-based tutoring may assist children in developing reading skills. There are no standardized interventions that occur outside of schools. In addition, home and community interventions may not be offered in all communities and the costs associated with them may be prohibitive for some families. There is a glaring need for additional accessible evidence-based interventions for dyslexia outside the school setting. Although the intersection between dyslexia risk from universal screening and MTSS as an intervention model for students with elevated risk levels has limited research, greater calls from the field suggest that preventive models in school systems should be considered (e.g., Catts & Hogan, 2021; Miciak & Fletcher, 2020). Overall these interventions need to be delivered in a highly structured manner with regular practice. Furthermore, multisensory teaching is recommended for children with dyslexia, where they use several senses simultaneously. For example, a child may be taught to see the letter "a," say its name and sound and write it in the air all at the same time. These techniques aim to improve dyslexia reading skills by focusing on sound-symbol relationships, using flashcards, teaching short words, and incorporating tactile learning (Agus and Ediyanto, 2021). The study by Schlesinger & Gray (2017) aimed to determine if simultaneous multisensory structured language instruction improved letter name and sound production, word reading, and word spelling for second-grade children with typical development or dyslexia compared to structured language instruction alone. The study found that the multisensory intervention did not have an advantage over the structured intervention for participants with typical development or dyslexia. However, both interventions had an overall treatment effect, although the effects varied depending on the outcome variable. An empirical review (Pennington, May 23, 2015) suggests that parents can play a significant role in helping children with dyslexia. Reading to the child, sharing reading, overlearning, and making reading fun are effective ways for parents to support their child's learning. The role of parents in supporting children with dyslexia is crucial, as highlighted in a newspaper article. However, societal pressures and potential humiliation can make it challenging for parents to accept and support their child with dyslexia. Headteachers need to convince parents to provide early assistance and support for the overall development of these children. In a 21st century driven by technology, SEND (dyslexia) can be mitigated with specific interventions and technologies (British Dyslexia Association, 2017). Technology can also be beneficial for children with dyslexia. Many children feel more comfortable working with a computer, as it provides a visual environment that suits their learning style. Word processing programs with spellcheckers and autocorrect features can help highlight mistakes in writing. Text-to-speech functions in web browsers and word-processing software can assist with reading. Speech recognition software can translate spoken words into written text, which can be helpful for children with better verbal skills than writing skills. Additionally, educational interactive software applications can provide a more engaging learning experience for children with dyslexia because their verbal skills are often better than their writing. A study by Alyaba (2014) developed a computer game application to help kindergarten children in Saudi Arabia who are at risk of dyslexia. The aim was to improve reading and listening skills, differentiate between sounds, and stimulate phonological awareness. The study found that the children were able to improve their reading skills and acquire necessary language skills through the game. These digital applications and programs represent tools that can be used in the home to help children with reading. The intervention for children with dyslexia was evaluated using the Rapdys© Assessment which measures the discrimination of voicing boundaries of phonemes in the French language (Serniclaes et al., 2017). These remedies were seen to effectively aid children with dyslexia in a great way. The empirical review on interventions for children with dyslexia by (Harrar-Eskinazi et al., 2022) found a specific interventions rapidly automatized naming training. This rapid automatized naming training is performed using a program called Naming Speed. The child is shown black-and-white drawings of objects and must name them as quickly and accurately as possible, following a set cadence. The training progresses by increasing the number of images and the naming speed. This training is also done for 10 minutes per day, 5 times per week. This intervention was found to help improve phonological skills and discrimination abilities in children with dyslexia.