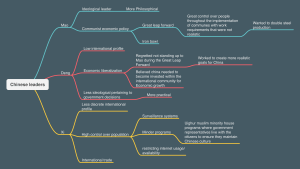

Still going strong China’s Communist Party at 100: the secret of its longevity Ruthlessness, ideological agility and economic growth have kept it in power On july 1st China’s Communist Party will celebrate its 100th birthday. It has always called itself “great, glorious and correct”. And as it starts its second century, the party has good cause to brag. Not only has it survived far longer than its many critics predicted; it also appears to be on the up. When the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, many pundits thought that the other great communist power would be next. To see how wrong they were, consider that President Joe Biden, at a summit on June 13th, felt the need to declare not only that America was at odds with China, but also that much of the world doubted “whether or not democracies can compete”. One party has ruled China for 72 years, without a mandate from voters. That is not a world record. Lenin and his dismal heirs held power in Moscow for slightly longer, as has the Workers’ Party in North Korea. But no other dictatorship has been able to transform itself from a famine-racked disaster, as China was under Mao Zedong, into the world’ s second-largest economy, whose cutting-edge technology and infrastructure put America’s creaking roads and railways to shame. China’s Communists are the world’s most successful authoritarians. The Chinese Communist Party has been able to maintain its grip on power for three reasons. First, it is ruthless. Yes, it dithered before crushing the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989. But eventually it answered bullhorns with bullets, terrorising the country into submission. China’s present leaders show no signs at all of having any misgivings about the massacre. On the contrary, President Xi Jinping laments that the Soviet Union collapsed because its leaders were not “man enough to stand up and resist” at the critical moment. For which read: unlike us, they did not have the guts to slaughter unarmed protesters with machineguns. A second reason for the party’s longevity is its ideological agility. Within a couple of years of Mao’s death in 1976, a new leader, Deng Xiaoping, began scrapping the late chairman’s productivity-destroying “people’ s communes” and setting market forces to work in the countryside. Maoists winced, but output soared. In the wake of Tiananmen and the Soviet Union’s downfall, Deng fought off Maoist diehards and embraced capitalism with even greater fervour. This led to the closure of many state-owned firms and the privatisation of housing. Millions were laid off, but China boomed. Under Mr Xi the party has shifted again, to focus on ideological orthodoxy. His recent predecessors allowed a measure of mild dissent; he has stamped on it. Mao is lauded once more. Party cadres imbibe “Xi Jinping thought”. The bureaucracy, army and police have undergone purges of deviant and corrupt officials. Big business is being brought into line. Mr Xi has rebuilt the party at the grassroots, creating a network of neighbourhood spies and injecting cadres into private firms to watch over them. Not since Mao’s day has society been so tightly controlled. The third cause of the party’s success is that China did not turn into a straightforward kleptocracy in which wealth is sucked up exclusively by the well-connected. Corruption did become rampant, and the most powerful families are indeed super-rich. But many people felt their lives were improving too, and the party was astute enough to acknowledge their demands. It abolished rural taxes and created a welfare system that provides everyone with pensions and subsidised health care. The benefits were not bountiful, but they were appreciated. Over the years Western observers have found plenty of reasons to predict the collapse of Chinese communism. Surely the control required by a one-party state was incompatible with the freedom required by a modern economy? One day China’s economic growth must run out of steam, leading to disillusion and protests. And, if it did not, the vast middle class that such growth created would inevitably demand greater freedoms — especially because so many of their children had encountered democracy first-hand, when they got their education in the West. These predictions have been confounded by the Communist Party’s continuing popularity. Many Chinese credit it for the improvement in their livelihoods. True, China’s workforce is ageing, shrinking and accustomed to ridiculously early retirement, but those are the sorts of difficulties every government faces, authoritarian or not. Vigorous economic growth looks as if it will continue for some time yet. Many Chinese also admire the party’s strong hand. Look, they say, at how quickly China crushed covid-19 and revved up its economy, even as Western countries stumbled. They relish the idea of China’s restored pride and weight in the world. It plays to a nationalism that the party stokes. State media conflate the party with the nation and its culture, while caricaturing America as a land of race riots and gun massacres. The alternative to one-party rule, they suggest, is chaos. When dissent emerges, Mr Xi uses technology to deal with it before it grows. Chinese streets are bristling with cameras, enhanced by facial-recognition software. Social media are snooped on and censored. Officials can solve problems early or persecute citizens who raise them. Those who share the wrong thought can lose their jobs and freedom. The price of the party’s success, in brutal repression, has been horrendous. No party lasts for ever The most dangerous threat to Mr Xi comes not from the masses, but from within the party itself. Despite all his efforts, it suffers from factionalism, disloyalty and ideological lassitude. Rivals accused of plotting to seize power have been jailed. Chinese politics is more opaque than it has been for decades, but Mr Xi’s endless purges suggest that he sees yet more hidden enemies. The moment of greatest instability is likely to be the succession. No one knows who will come after Mr Xi, or even what rules will govern the transition. When he scrapped presidential term limits in 2018, he signalled that he wants to cling to power indefinitely. But that may make the eventual transfer only more unstable. Although peril for the party will not necessarily lead to the enlightened rule that freedom-lovers desire, at some point even this Chinese dynasty will end. (2) China ’ s online-education crackdown business on marks the a turning-point Less capitalism, more state To get rich is glorious, Deng Xiaoping supposedly said. “To get as rich as Jack Ma is clearly not so glorious,” quipped an investor last November when the initial public offering of Mr Ma’s Ant Group was cancelled on the say-so of China’s financial regulators. A lot of foreign investors interpreted it as a slap-down to China’s best-known billionaire and thus a warning to the country’s other plutocrats not to get too big for their boots. But in the months since then the scope of the regulatory crackdown has grown ever wider. China’s two internet giants, Alibaba and Tencent, are being worked over by the antitrust authorities. Earlier this month Didi Global, a ride-hailing service, was caught in the net just days after it listed in New York. And in the past week the education-technology industry has become a target. New regulations bar any company that teaches subjects on the school curriculum from listing abroad, having foreign investors or making profits. When it comes to teaching schoolchildren, no one should get rich. The market response to the latest bureaucratic diktat was a sharp sell-off. The share prices of a trio of Chinese online-tutoring firms listed in New York fell by two-thirds. The panic spread to other Chinese firms listed in America. The Nasdaq Golden Dragon China Index, which tracks the biggest stocks of this kind, fell by almost 20% over three days. The contagion took in China’s onshore market, with share prices down across the board.  China’s preferences now seem clear. It wishes to see capital raised on its own exchanges, within its purview and on the terms that it dictates. The effects of this on financial markets are likely to linger. China itself may be the biggest loser. Start with the effect on the market value of tech firms outside China. The tech-heavy Nasdaq index also sold off in response to the rout of Chinese tech stocks, because the latest episode signalled that investing in technology carries regulatory risk. In America Joe Biden’s administration has also sought to strengthen oversight of big tech, by beefing up antitrust. But trustbusting in America takes place in a legal context. There is a body of jurisprudence that limits how far the authorities can go in clipping the wings of tech giants, even those making profits many find obscene: Alphabet, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft all reported a record second-quarter haul this week. If Chinese rivals are mired in red tape, that is all to the good of big tech in America. And the clampdown will indeed harm Chinese tech. Investors who piled in during recent years have this week been pummelled in public markets. Private American capital is also tied up in Chinese startups. The value in those ventures is now, in effect, frozen. The route to an ipo for a young Chinese firm—the reliable way for venture capitalists to get their money back—now borders on perilous. A lot of Chinese firms have raised money abroad in vehicles known as variable-interest entities, which are essentially synthetic shares. This route may now be blocked for ever. And venture capitalists will surely be charier about backing Chinese tech startups, however promising. Still more worrying is that any investment, even in an onshore non-tech firm, is now at risk from arbitrary rule changes. That will raise the cost of capital for Chinese firms. China’s securities regulator hastily convened a meeting with international bankers this week to reassure them that only education-based firms were being targeted. It suggests that China’s policy brass, having startled markets, have realised that they may have miscalculated. It certainly looks that way. The capital markets are not a tap that regulators can turn on and off when it suits them. True, investors’ memories can be short. But China is gaining a reputation for regulatory high-handedness that it can shed only by starting to follow transparent rules—and that is precisely the sort of subordination the Communist Party abhors.