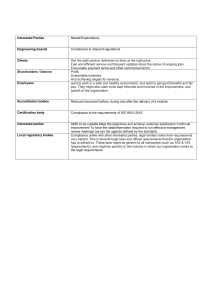

Report ISO 22000:2018 Understanding the international standard Contents 01. Introduction 3 02. Purpose of this report 4 03. Executive summary 5 3.1 Summary of principal changes: Moving from ISO 22000:2005 to ISO 22000:2018 5 3.2 Food safety-specific requirements 7 3.3 FSSC 22000 8 04. Clause-by-clause review 9 05. Conclusions 65 Appendix A: Summary of required documented information 66 Appendix B: FSSC 22000 and GFSI 67 quality.org | 1 01. Introduction Since its launch in 2005, ISO 22000 has been adopted as the food safety management system (FSMS) standard of choice for more than 32,000 organisations worldwide. In addition, over 23,000 organisations have been certified under the FSSC 22000 private certification scheme, whose core requirements are based on ISO 22000. Given that many of the organisations operating to the ISO 22000 or FSSC 22000 standards are global players in the food manufacturing and processing sectors, these figures illustrate the considerable influence that the standard exerts on global food safety. ISO 22000:2018 was the first major revision to the standard since its launch. It affects not only those organisations that wish to maintain their system certification, but also other interested parties such as certifying bodies, that are involved in the associated auditing programmes. quality.org | 3 02. Purpose of this report This report is intended to inform CQI members and IRCA certificated auditors who have a relevant interest in food safety management systems, and to offer insight and assistance to those implementing, managing and auditing ISO 22000:2018-based management systems. ISO 22000:2018 adopts the high-level structure of Annex SL, the shared framework that is common to all new ISO standards. It also adds disciplinespecific requirements that must be considered by all food safety professionals. Section 3 of this report comprises an executive summary providing a short overview of the standard, its application and how it compares with the 2005 version. In section 4, we discuss the contents of ISO 22000:2018, describing each clause in plain English and considering the implications for those tasked with overseeing the operation of food safety management systems, and those engaged in auditing them. In section 5 we summarise the benefits we expect all interested parties will reap from the application of ISO 22000:2018. 4 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 03. Executive summary As with other recently revised ISO standards including ISO 9001 and ISO 14001, a three-year transition period (ending 29 June 2021) was initially set for organisations with certified ISO 22000:2005 management systems wishing to gain certification to ISO 22000:2018. However, owing to the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, the International Accreditation Forum (IAF) extended the transition period by six months to 29 December 2021, and confirmed that transition audits may be done using remote audit techniques. 3.1 Summary of principal changes: Moving from ISO 22000:2005 to ISO 22000:2018 CONTEXT (Clause 4) Organisations are required to identify any external and internal issues that may affect the ability of their food safety management system to deliver its intended outcomes. These outcomes are the continual improvement of food safety performance, fulfilment of legal and other requirements, and achievement of food safety objectives. Organisations are also required to determine the relevant needs and expectations of their relevant interested parties – i.e. those individuals and organisations that can affect, be affected by, or perceive themselves to be affected by, organisations’ decisions or activities. LEADERSHIP (Clause 5) Top management are required to demonstrate that they engage in key FSMS activities, as opposed to simply ensuring that these activities occur. This means there is a need for top management to be seen to be actively involved in the operation of the FSMS and accountable for its results. RISK-BASED THINKING (Clause 6) Organisations must demonstrate that they have determined, considered and, where deemed necessary, taken action to address any risks and opportunities that may affect (either positively or negatively) the ability of their FSMS to deliver its intended outcomes. These risks can be categorised in two levels: a) policy level, usually managed by the top management and related to the organisation’s strategic planning and views, and b) operational level, which covers those risks related directly to food safety, and already addressed by ISO 22000:2005 through the application of the HACCP (hazard analysis and critical control points) technique and control measures like CCPs (critical control points) and OPRPs (operational prerequisite programmes). quality.org | 5 “There has been a conscious attempt to revisit the wording of the standard with a view to making the requirements easier to understand and to aid its translation” COMMUNICATION (Clause 7) Communication with interested parties plays an important role in an effective FSMS. Organisations need to be sure that the information provided is consistent with the information generated within the FSMS, i.e. that it is accurate, timely and properly directed. OPERATIONS (Clause 8) Organisations need to control their operational processes by a) managing temporary and permanent changes under controlled conditions, b) ensuring that outsourced processes are controlled, c) controlling the procurement of products and services, and d) ensuring that all staff meet the requirements of the FSMS. IMPROVEMENT (Clause 10) Improving the organisation’s food safety performance and the food safety management system (as two separate issues) was already required by ISO 22000:2005. In ISO 22000:2018, these requirements are stressed in several clauses as one of the functions of the FSMS. TERMINOLOGY (Clause 3) This clause contains the terms and definitions used in the standard, irrespective of whether they come from Annex SL or were added by the technical committee for food safety management systems, ISO/TC 34/SC17. The revised standard contains many notes for clarification of the context for terms and definitions. ANNEXES ISO 22000 has two informative annexes. The first provides a comparison between ISO 22000:2018 and the Codex HACCP system published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s Codex Alimentarius Commission. The second provides a cross reference between the revised 2018 version of ISO 22000 and the earlier 2005 version. DOCUMENTED INFORMATION References to requirements for documents and records have been replaced by the term “documented information”. “Maintained documents” comprise procedures, policies, plans etc. that need to be available to perform an activity, while “retained documents” contain retrievable information e.g. of measurement and monitoring. Control of documented information continues to be a requirement. CLARITY There has been a conscious attempt to revisit the wording of the standard with a view to making the requirements easier to understand and to aid its translation. 6 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 3.2 Food safety-specific requirements The main food safety-specific additions to the basic Annex SL requirements are related to: » Planning of changes (6.3) » Prerequisite programmes (8.2) » Traceability system (8.3) » Emergency preparedness and response (8.4) » Hazard control (8.5) » Updating the information specifying the PRPs and the hazard control plan (8.6) » Control of monitoring and measuring (8.7) » Verification related to PRPs and the hazard control plan (8.8) » Control of product and process nonconformities (8.9) Many of these were included in the previous version of the standard. In ISO 22000:2018 they have been revised and upgraded to fit into a more strategically positioned management system. quality.org | 7 3.3 FSSC 22000 Version five of FSSC 22000 was published by Foundation FSSC 22000 in June 2019, 12 months after the initial version of ISO 22000:2018. It follows the structure of ISO 22000:2018, which means it is far more aligned with the new ISO high-level structure than the previous version, FSSC 22000 v4.1.The FSSC 22000 v5 standard also follows ISO 22000:2018 in many other key improvements, including the use of two interdependent and linked PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycles, plus the distinction between risk and opportunity of the organisational management systems and strategic goals as a whole, as well as risks at an operational level (clause 8 of FSSC 22000 v5). As ISO 22000:2018 has undergone a significant update, some of the FSSC-specific requirements in v5 have been condensed. For example, FSSC 22000 v5 clause 2.5.1 Management of services has been shortened, because this is now part of ISO 22000:2018 clause 7.1.6. However, Management of laboratory services remains as an additional FSSC 22000 requirement. The harmonisation of the two standards is likely to be welcomed by organisations in the food and beverage supply chain operating to one or the other, or even both across their various sites. Full clause-by-clause change analysis of FSSC 22000 v5 can be found on BSI’s website, bsigroup.com. For more on FSSC 22000’s relationship to the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI), see Appendix B. 8 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 04. Clause-by-clause review Note: The interpretations of the requirements of ISO 22000 contained in this document are those of the CQI. Other organisations may interpret the requirements of the standard differently. As such, this document should not be viewed as a definitive reference source for this international standard; indeed, only documentation published by the relevant ISO committee, ISO/TC 34/SC17, can fulfil this purpose. Please note: The CQI is not permitted to quote from the standard due to copyright restrictions. Anyone needing the exact wording should source the standard from a legitimate supplier. This section of the report aims to: » simplify the requirements of each clause of ISO 22000 into language that is easier to understand » identify the implications of the requirement for food safety professionals (food safety managers, directors, system implementers) » identify the implications of the requirement for audit professionals Introduction The introduction to ISO 22000:2018 reminds us that organisations are responsible for the food safety issues of their involvement in the food chain. Organisations can demonstrate that they are fulfilling this responsibility by implementing a food safety management system based on ISO 22000, which can assure customers and consumers that they can consistently meet food safety requirements and relevant legal requirements. Implementing an FSMS conforming to ISO 22000 also enables organisations to manage and control their food safety hazards and improve their food safety performance. The implementation of an FSMS is a strategic and operational decision for organisations. The success of a food safety management system depends on leadership, commitment and participation from all levels and functions in the organisation. quality.org | 9 “Users of the standards must appreciate that the adoption of ISO 22000 does not necessarily guarantee a specific level of food safety performance” Top management input is essential to achieving these benefits. Managers must recognise their role in effectively addressing food safety risks and opportunities, in integrating food safety management into the organisation’s business processes, strategic direction and decision-making and, most of all, by incorporating sound food safety governance into the organisation’s overall management system. Users of the standards must appreciate that the adoption of ISO 22000 does not necessarily guarantee a specific level of food safety performance. Two organisations with similar activities may have different interested parties, may face different external and internal issues, may start implementing their food safety activities from different baselines and may wish to improve at different rates, and yet both can conform to the requirements of the standard. Clauses 1 to 3 of the standard set out its scope of application, normative references and terms and definitions. The information contained in clause 3, in particular, is important in understanding subsequent clauses, and must not be overlooked. Clauses 4 to 10 contain the requirements to be met during the implementation of the FSMS and during its conformity assessment. Clause 4 sets the context for the FSMS itself and its constraints (internal and external issues and the requirements of interested parties), while clause 5 defines the leadership “engine” that drives the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle embodied in the framework of the standard. Clauses 6 to 10 follow the PDCA cycle. The relationship can be seen as follows: 1 PLAN » Plan in clause 6 4 2 ACT DO 3 CHECK 10 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard » Do in clauses 7 and 8 » Check in clause 9 » Act (for improvement) in clause 10 In addition to the 10 main clauses, there are two annexes that provide a comparison between Codex HACCP and ISO 22000:2018 as well as a cross reference between the revised 2018 version and the earlier 2005 version. There is also a bibliography which makes reference to other related ISO standards and other documents relating to food safety. In the standard, the following terms are used: a. “shall” indicates a requirement b. “should” indicates a recommendation c. “may” indicates permission d. “can” indicates a possibility or a capability Note that a) is mandatory while b), c) and d) are optional at the discretion of the user. However, organisations may benefit from assessing and justifying the reasons for not implementing these optional requirements. In many sections a note is included for guidance in understanding or clarifying the associated requirement. These notes are not, in themselves, requirements. Some entries in clause 3 provide additional information that supplements the terminology and can contain provisions relating to the use of a term. Any organisation that wishes to demonstrate conformity to the standard can make a self-determination and self-declaration, request interested parties to confirm its conformance, have its self-declaration reviewed by third parties, or get its FSMS certified by independent third parties, usually accredited certification bodies. quality.org | 11 1. Scope This section lays down the foundation of a food safety management system to enable an organisation to provide products and services that are safe for their intended use, as well as improving its food safety performance. This will involve complying with food safety legislation, meeting customer food safety requirements, communicating food safety issues to relevant parties, delivering the organisation’s food safety policy and demonstrating conformance to the standard either by self-declaration or by external certification. This standard is applicable to organisations of any size and type, engaged in any kind of activity associated with the food chain. However, it does not state any specific criteria for food safety performance, does not prescribe any specific format for the FSMS, and does not address issues like product quality or environmental impact in as far as they do not affect the food safety of products and processes. The standard applies to any and all sizes of organisation including those that may use external resources to assist with their conformance to requirements both for initial implementation and ongoing maintenance. 2. Normative references There are no normative references applicable to this standard. There is no other standard or document that contains requirements in addition to those included in the main text (clauses 4 to 10). 3. Terms and definitions This section contains the common terms and core definitions included in Annex SL, plus those terms and definitions added to complement the food safety-specific text drafted by the technical committee ISO/TC 34/SC17. There are some terms that are self-explanatory and can be used straightforwardly. However, there are a few whose definitions need to be more carefully considered in order to fully understand the requirements in which they are used. Key terms that deserve to be analysed in detail are: action criterion, documented information, effectiveness, critical control point (CCP), measurement, monitoring, interested party, outsource and risk. 12 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 4. Context of the organisation 4.1 Understanding the organisation and its context INTERPRETATION ISO 22000 is focused on food safety. However, addressing everyday legal and operational food safety issues may not be enough to ensure that the FSMS achieves its intended outcomes. The standard requires organisations to move beyond this, and to identify, review and keep updated, internal and external issues that are relevant to the organisation’s purpose, and that may affect its ability to achieve the intended outcomes of the FSMS. External issues may, for example, be related to government policy, economics, society, technology, finance, legislation, environment, supply chain and defence, that can represent a threat or opportunity to the effective operation of the organisation’s FSMS. Internal issues may be related to governance, strategies, culture, activities, products and services, infrastructure, capabilities, cybersecurity, food fraud, food defence or other issues that might constitute a strength or weakness of the organisation’s FSMS. The standard does not prescribe who within an organisation will be responsible for complying with this requirement. Nevertheless, it is highly probable that top management will be closely involved – these issues are likely to be related to strategic and business process elements of the organisation, and must be reviewed during planned management review meetings. The standard does not require organisations to document this contextual information. However, it would be wise, for control and demonstration purposes, to maintain at least some of this information in documented form. Some of the contextual issues determined by the organisation may result in risks and opportunities to the organisation’s FSMS. In clause 6.1, organisations are required to determine which ones pose a potential risk or opportunity, and to take proportionate action to address them. Implications for food safety professionals Most organisations should already be successfully monitoring internal and external issues that have the potential to affect not only their FSMS but the whole organisation. quality.org | 13 “Auditors will also need to understand the external and internal issues typically experienced in organisations” The standard requires the organisation to use this knowledge to establish the scope of its FSMS, to design, implement and continually improve it, and to determine risks and opportunities associated with food safety. Food safety professionals are used to dealing mainly with everyday operational issues. Now, they will need to embrace a wider picture, taking into account how food safety matters are embedded in the organisation’s business environment. They will likely be required to share their knowledge and experience with top management. In many organisations, the dialogue between food safety professionals and top management is mainly focused on operational aspects of food safety. This requirement (and others in the standard) represents a good opportunity for food safety professionals to expand the dialogue with top management to cover strategic matters, if such exchanges do not already take place. Implications for audit professionals Auditors will need to allow additional time to prepare for audits in order to establish their understanding of the context in which audited organisations operate. The preparation for the audit may include a thorough search of all available information on the organisation itself (e.g. from the organisation’s website) and on the food chain sector (e.g. information on business trends and the state of the global market and natural environment). Auditors will also need to understand the external and internal issues typically experienced in organisations and must be ready and able to challenge top management if they believe an organisation’s interpretation of its context is deficient or incorrect. Like food safety professionals, auditors will have to be aware of generic issues related to the business life of organisations, and not limit their interactions with top management to operational food safety issues. A thorough familiarity with the organisation’s processes and its role in the food chain, will be vital. Auditors will be required to audit this requirement with the top management. This represents quite a challenge to the auditor skillset. Auditing this requirement only with middle managers or with the food safety manager or team leader will probably not cover the required scope. Evidence needs to be obtained to provide assurance that organisations are reviewing and regularly updating the external and internal issues that they have identified. If the organisation decides not to maintain documented information on the relevant issues, this will pose a challenge to auditors, and face-to-face interviews will be essential. 14 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 4.2 Understanding the needs and expectations of interested parties INTERPRETATION The first step is to identify the organisation’s “interested parties” as defined in clause 3.23 of the standard. Examples of interested parties include regulatory authorities, suppliers, contractors, subcontractors, owners, customers, local government agencies and trade organisations. The second step is to determine which of those interested parties are relevant to the FSMS. The third step is to determine which needs and expectations of those relevant interested parties may be associated with the FSMS. This clause requires organisations to determine, review and regularly monitor information on the relevant needs and expectations of interested parties. The term “relevant” has to be read as “pertinent to food safety”, and it is the organisation, not the auditor, who decides what is relevant and what is not. Some of these requirements may result in risks and opportunities to organisations. In clause 6.1, organisations must determine which requirements represent a potential risk or opportunity and take action to address them. As in clause 4.1, the standard does not require organisations to keep contextual information documented. However, it would be wise, for control and demonstration purposes, to maintain key information in documented form. Implications for food safety professionals It is easy to imagine that ISO 22000, being a food safety-related standard, will establish requirements mainly affecting food safety professionals. But as in clause 4.1, top management need to play a key role. Food safety professionals can assist management by playing the role of facilitator or providing support to their decision-making on food safety policy and strategy. However it is top management who must decide, and provide information on, what needs and expectations are relevant to the organisation. quality.org | 15 Note that the standard does not require all requirements of all interested parties to be met. The idea is that meeting the relevant requirements of interested parties (i.e. those that pose unacceptable risks or present opportunities) will allow the organisation to be in a better position to ensure that the FSMS produces the expected results (see clause 1). Implications for audit professionals The comments on implications for audit professionals in clause 4.1 are fully applicable to clause 4.2 also. 4.3 Determining the scope of the FSMS INTERPRETATION When designing the FSMS, the organisation has to define its scope, which sets its boundaries, its organisational functions, and the activities, products and services within the organisation’s control or influence that can have an impact on its food safety performance. When defining the scope of its FSMS, an organisation needs to: a. consider the internal and external issues it faces as part of the context b. take into account legal requirements c. take into account the requirements of relevant parties The scope of the FSMS has to be documented. Implications for food safety professionals An organisation has the freedom to define its own FSMS boundaries. It may choose to develop an FSMS for the entire organisation or for some specific part of the organisation – but only if the top management of that part of the organisation has the authority and resource to implement the FSMS. The credibility of an organisation’s FSMS depends on, among other factors, the choice of the FSMS scope. In order not to mislead interested parties, the scope should not exclude activities, products and services, internal or external, that have a significant impact on food safety performance or that are related to legal requirements. As was the case with clauses 4.1 and 4.2, the definition of the scope should be decided by top management. Food safety professionals may assist them in this, but it is clearly a strategic decision for the organisation. 16 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “An organisation has the freedom to define its own FSMS boundaries” Implications for audit professionals Auditors must gather evidence that the scope has been correctly defined considering the organisation’s context and taking into account the applicable legal requirements as well as the organisation’s activities, products and services. Auditors will also have to evaluate the accuracy of the scope as derived by the organisation and determine if, as defined, the scope may mislead interested parties on what is and is not covered by the FSMS. Auditors will also need to verify that the organisation’s scope is maintained as documented information and is up-to-date. quality.org | 17 4.4 Food safety management system INTERPRETATION Clause 4.4 sets out high-level generic requirements for the food safety management system. Organisations have to establish a management system that complies with all requirements of ISO 22000. Once established, the FSMS needs to be implemented, maintained and continually improved. When developing the management system, the organisation has to determine the processes needed and how they interact. It is also expected that the processes included in the FSMS will, whenever practicable, be fully integrated into the business processes of the organisation. When developing the FSMS, and once all the processes needed have been identified, the organisation has to determine which ones, if any, will be outsourced or externally provided. The outsourced processes will have to remain under the control of the FSMS, as established in clause 8.1. Implications for food safety professionals The organisation has the authority to decide how it will meet the requirements in clause 4.4. Food safety professionals will have a key role in the development of the FSMS. To do so, they will have to thoroughly research the organisation, and understand all its processes and their interactions. In the case of an FSMS applied to a specific part of an organisation, they will have to identify which policies and processes applied in other parts of the organisation may need to be incorporated into the FSMS being developed. Implications for audit professionals This clause contains high-level requirements that span across all other clauses of the standard. Auditors will need to take this into account when auditing all other requirements, and will then need to make a high-level evaluation as to the organisation’s degree of conformance with all the requirements in the standard. Raising a nonconformity against this requirement would only be possible if auditors find evidence of issues that span most of the FSMS processes and raise serious doubt as to whether a viable FSMS is in existence. 18 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 5 Leadership 5.1 Leadership and commitment INTERPRETATION This is a key clause and is fundamental to the whole standard. If it is not followed in its basic and profound meaning, the whole management system may still achieve some good results, but will fail to reach its full potential. With reference to the food safety management system, top management must demonstrate leadership and commitment to everyone in the organisation, as well as to other interested parties such as suppliers and customers. This is something that top management must demonstrate in tangible ways. This starts with them accepting accountability for the effectiveness of the FSMS, being involved where and when necessary, communicating what is required and taking action accordingly. They must ensure that the food safety policy and objectives are consistent with the organisation’s overall strategic direction and the context in which the organisation is operating. They must use their authority to ensure that the objectives of the FSMS are realistic and compatible with the food safety policy of the organisation. In addition, top management must ensure that the food safety policy is communicated, understood and applied across the organisation and that the FSMS achieves the intended results. Top management must also ensure that the requirements of the FSMS are integral to the organisation’s business processes and that resources are available for its effective operation. Top management must provide leadership to those who contribute to the effective operation of the system. They must also encourage leadership in food safety in other management roles. Implications for food safety professionals The emphasis on “leadership and commitment” is perhaps the most significant requirement and fundamental change contained in ISO 22000:2018, although the actual impact will depend very much on the current position of each individual organisation. quality.org | 19 “When ISO 22000 uses the term ‘top management’, it is referring to a person or a group of people who direct and control an organisation at the highest level” For those organisations whose most senior members currently play an active role in driving the FSMS forward, the revised requirements will likely involve a formalisation of current practice. However, for those organisations where top management have little involvement in the FSMS, effectively devolving responsibility for their FSMS to other levels in the organisation, the impact of the requirement of this clause will be significantly greater. Where the word “ensuring” is applicable to an activity within the standard, top management may still assign this task to others for completion. Where the words “promoting”, “taking”, “engaging” or “supporting” appear, these activities cannot be delegated and must be undertaken by top management themselves. Top management will need to be made aware of the revised requirements including the fact that they will be audited as a matter of routine and on a wide set of issues. Food safety professionals can help to support top management in fulfilling their revised responsibilities by suggesting strategy options, encouraging personal development and regularly reporting on all aspects of the FSMS. When ISO 22000 uses the term “top management”, it is referring to a person or a group of people who direct and control an organisation at the highest level. Implications for audit professionals Auditors must ensure that they are well equipped to interview top management in respect of their leadership and commitment to their FSMS. To be effective and gain the respect of top management, auditors will need to have a good understanding of corporate affairs, of management roles, of the organisation they are auditing and the business context surrounding it. They will have to be able to engage with top management on a range of subjects by conversing in an intelligent way. Auditors who fail to adequately prepare for top management interviews will risk damage to their reputation and that of the auditing profession. For many auditors, this implies developing revised and enhanced knowledge, skills and behaviours. There will not be much documented information as evidence of leadership and commitment. Gathering evidence from top management will mainly involve discussion and cross-checking of responses with other members of the organisation being audited. Audit trails across the FSMS will reveal the extent to which leadership and commitment are exercised in the system. 20 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 5.2 Food safety policy INTERPRETATION Top management must establish a food safety policy that is consistent with the purpose and context of the organisation. The policy represents a top management commitment on how to ensure the alignment of food safety management to the long-term strategic intentions of the organisation. It must additionally provide a framework for setting and reviewing food safety objectives. Two specific commitments have to be included in the policy: to comply with legal and agreed customer requirements, and to continually improve the FSMS. It is the responsibility of top management to review and maintain a documented food safety policy, to communicate it within the organisation, to ensure that it has been understood and to make it available to interested parties. Implications for food safety professionals As it is top management themselves who are required to establish a food safety policy, they should not devolve this task to food safety professionals, and by the same token, food safety professionals should not be tempted by top management to do the job for them (e.g. to draft a policy to be reviewed by top management and who may then sign it without due consideration of its contents). Food safety professionals can support top management by ensuring that they are aware of the policy requirements in the standard and by reviewing their draft policy for conformance. Implications for audit professionals Auditors should discuss the policy in detail directly with the top management. If they are redirected to a management representative or food safety team leader, this probably has implications regarding top management commitment. The requirement to determine that the food safety policy is appropriate to the purpose and context of the organisation reinforces the need for auditors to establish their personal understanding of the context that the audited organisation is operating in. However, from an auditor perspective it is important that top management can demonstrate, from their own understanding, that the policy is compatible with the strategic direction and context of the organisation and that it has been communicated and understood throughout the organisation. quality.org | 21 Communication of the policy could be demonstrated by posters on the walls, but effective communication is two-way. Therefore, auditors should also ask staff about their understanding of the organisation’s policy. 5.3 Organisational roles, responsibilities and authorities INTERPRETATION The top management of the organisation needs to ensure that defined responsibilities and authorities are assigned to individuals in the organisation to carry out FSMS-related activities under their control. Specifically, they need to assign responsibility and authority for: » ensuring that the requirements set out in ISO 22000 are met » reporting on the operation of the FSMS » appointing a food safety team and team leader Top management must ensure that such responsibilities and authorities relating to the organisation’s FSMS are communicated and understood within the organisation, along with the reporting of any food safety issues to designated staff. Implications for food safety professionals Assigning roles within the FSMS is the responsibility of top management. A food safety team leader and their team play a vital role in the effective operation of the FSMS, and they can and should support top management by providing strategy options, nominating roles for individuals or teams, suggesting personal development opportunities, and assisting with communication throughout the organisation, etc. However, ownership of the FSMS must not centre on these individuals to the effective exclusion of top management. The organisation may have to revisit the existing responsibilities and authorities with regard to the FSMS, especially the responsibilities of top management and any food safety team leader. The review may identify gaps in resources, including gaps in competence which will then need to be addressed before a compliant system can be established. 22 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “FSMS planning is an ongoing activity which must continue throughout the life of the system, in the perpetual PDCA cycle” Implications for audit professionals Auditors must seek evidence that all personnel have not only been advised of their food safety responsibilities and authorities, but that they also understand these in the context of what the FSMS is trying to achieve. Auditors should note that there is a requirement for top management to appoint a food safety team and team leader. 6 Planning Planning in management systems is often viewed as something that relates mainly to setting up the system. While this is very important, the standard makes it clear that FSMS planning is an ongoing activity which must continue throughout the life of the system, in the perpetual PDCA cycle. quality.org | 23 6.1 Actions to address risks and opportunities INTERPRETATION As part of risk-based thinking, organisations are required to consider their context (4.1), the relevant requirements of their relevant interested parties (4.2) and the scope defined for the FSMS (4.3) when determining risks and opportunities. This means thinking about the internal and external issues they face, the requirements of interested parties within the defined scope of the FSMS, and the impact this may have on systems and processes. Note that risk-based thinking not only applies to product and process operations as part of the HACCP process but to business and system functions in relation to food safety. The scope of planning should be wide enough to provide assurance that the FSMS is able to achieve its intended results, to prevent or reduce undesired effects, and to achieve continual improvement. For every external and internal issue and for every relevant need and expectation of an interested party, a risk source may be identified. The determination of risks and opportunities should be carried out at both strategic and operational levels: » those directly related to operational processes can be defined as “food safety risks” and “food safety opportunities” » those related to strategic levels can be defined as “risks to the FSMS” and “opportunities for the FSMS” In the case where determination of risk or opportunity requires action, the standard requires a planned and systematic approach with respect to these actions, with the actions being integrated into the FSMS or other business processes when practicable. Subsequently each action must be evaluated to determine whether it was effective. Implications for food safety professionals The requirement for organisations to determine those risks and opportunities that have the potential to affect the operation and performance of their FSMS, both positively and negatively, presents a new challenge for food safety professionals. This extends the work of the food safety professional to interacting with top management, since these risks and opportunities will be related to organisational issues. 24 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “Auditors should ensure that the organisation is taking a planned and structured approach to addressing risks and opportunities” There is no specific requirement for a formal organisation-wide risk management or for a complicated risk management methodology (e.g. complex tables or grading scales of formulae) since the level of complexity of the methodology depends on the complexity of the business and the nature of the hazards, events, risks and opportunities determined. Actions taken to address risks and opportunities should be in proportion to the potential impact of the risk and opportunity on food safety or on the FSMS. However not all risks and opportunities need actions. For example, organisations may take an informed decision to accept the risk, taking no action beyond identifying and evaluating it, including ongoing evaluation. The actions planned may include establishing objectives (see 6.2 below) or incorporating the action into other FSMS processes. Subsequently, organisations need to evaluate the effectiveness of those actions. Implications for audit professionals Auditors should seek evidence that confirms that an organisation has an appropriate and consistently applied methodology in place to effectively identify risks and opportunities in the planning of their FSMS. Auditors must clearly understand the difference between “operational” and “strategic” risks and opportunities and decide who, within the audited organisation, should be interviewed. It is likely that “operational” risks would be audited with the food safety team, operational supervisors and non-managerial workers, while “strategic” risks would be audited with members of the top management and FSMS management. The role of the auditor is not to carry out their own determination of risks and opportunities, but to ensure that the organisation is applying its own methodology consistently and effectively. However, where the auditor’s knowledge of the context of the organisation reveals that the organisation has failed to identify a commonly known risk or opportunity, they may question the organisation’s approach. Auditors should ensure that the organisation is taking a planned and structured approach to addressing risks and opportunities. For those actions that have been completed, auditors should ensure that each action’s effectiveness has subsequently been assessed. They should also ensure that the action taken was proportionate to the risk or opportunity by determining the reason behind it. Auditors must ensure they have a good understanding of the concepts of risk and opportunity in the context of the FSMS and of the range of methodologies that organisations may use to manage these areas. quality.org | 25 6.2 Objectives of the food safety management system and planning to achieve them INTERPRETATION The definition of objective is “result to be achieved”. Note that an objective can be expressed in different ways, e.g. as an intended outcome, a purpose, an operational criterion, as a food safety objective, or in terms with similar meaning (e.g. aim, goal, or target). The term “FSMS objective” narrows down the broader meaning of “objective” to mean an objective set by the organisation to achieve specific results consistent with the food safety policy. An FSMS objective may be defined at various levels: strategic, cultural, project, product, service or process. This clause applies only to “FSMS objectives” and requires organisations to set them for relevant functions, levels and processes within its FSMS. It is up to the organisation itself to decide which functions, levels and processes are relevant. It would be expected that the organisation would prioritise objectives to deal with, for example, the hazards associated with the highest risk factors. The organisation has to define objectives in order to maintain and continually improve its FSMS and its food safety performance. This means that organisations may set objectives on some processes to ensure that a certain level of performance is maintained, and on other processes to achieve a performance improvement. When defining its objectives, the organisation must take into account the results of the assessment of risks and opportunities, the requirements of the standard and the applicable legal requirements. Any objectives set must be measurable or capable of performance evaluation, communicated and updated as appropriate. They must also be monitored in order to determine whether they are being met. Setting objectives is not a one-off activity. It should be an ongoing, recurring process that plays an important role in the continual improvement of the FSMS. The organisation has to maintain and retain documents providing information on the FSMS objectives and its plans to achieve them. 26 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals need to be aware that, as mentioned above, the use of “objectives” is not limited to improvement processes. An objective may be set in order to maintain a certain level of performance. Organisations may need to define objectives at different levels. When doing so, they need to ensure the alignment of those objectives to their strategic direction. Note that the concept of a “target” used in other management system standards is contained within the term “FSMS objective”. There is no material difference between objectives and targets in ISO 22000. Objective planning includes what needs to be done, but also what resources will be required to do it, who will do it, when it will be completed and how it will be evaluated in order to determine if results have realised the objective. Food safety professionals will need to interact with most, if not all, functions of the organisation in order to facilitate the setting of objectives. Implications for audit professionals Auditors will need the competence to audit a set of interrelated objectives, ensuring that they are mutually consistent and aligned with the strategic direction of the organisation, particularly those relating to improvement of the FSMS. Auditors should look for evidence that effective planning is taking place to support the achievement of the organisation’s FSMS objectives, including the use of measurement or monitoring indicators, which need to be audited in detail. quality.org | 27 6.3 Planning of changes INTERPRETATION Change management in the FSMS is an important requirement that needs to be carried out and communicated in a planned and orderly manner. This includes changes to personnel, especially those who have an impact on the FSMS such as food safety team leaders and members. This requirement strengthens that previously in the 2005 version of the standard (clause 5.3) by adding factors such as the purpose of change, its consequences, resource needs and allocation of responsibilities to be considered. Such factors are likely to involve top management. The standard does not require organisations to keep change planning considerations in documented form. However, it would be wise, for control and demonstration purposes, to record this information e.g. in minutes of management meetings. Implications for food safety professionals Changes to the FSMS can have an impact on many interrelated processes so food safety professionals have to ensure that the integrity of the system is maintained throughout the change process and beyond. This will likely require greater consultation with top management and management of other functions before any changes are made. Food safety professionals can advise on competence needs where personnel changes are envisaged, and recommend any need for the setting of new objectives or changes to existing objectives. Changes to risk management strategies, both corporate and operational, will benefit from the input of food safety professionals. 28 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “The standard does not require organisations to keep change planning considerations in documented form” Implications for audit professionals Changes to the FSMS have the potential to render it vulnerable to failing due to unintended consequences or omissions, resulting in a risk to food safety. Auditors need to ensure that the change process is robust and consistently applied. In the absence of documentation, auditors will need to gather evidence through interviews with top management, food safety team leaders and members and managers of relevant functions. Understanding of what the change means for the FSMS needs to be combined with an understanding of how it is implemented and whether it is working effectively. 7 Support Clause 7 is part of the “Do” step of the PDCA cycle, where necessary resources are considered in order to be able to do what was planned in clause 6. 7.1 Resources 7.1.1 General INTERPRETATION The organisation must initially determine and provide the resources necessary to establish, implement, maintain and continually improve its FSMS. Release of resources is a function of management at the top level of the organisation. The extent of the provision of resources can be a limitation on the effectiveness of the FSMS. Examples of resources include people, raw materials, infrastructure (including buildings, equipment and utilities), finance, IT and software, communications and emergency containment, all of which can be either internally or externally provided. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals should ensure that the different types of resources needed for the FSMS are identified. Resources can be tangible or intangible, such as intellectual property. Implications for audit professionals Auditors should check that the organisation has identified all types of resources required by the FSMS, and that those resources will be available when needed. There are likely to be budgetary considerations relating to the management of resources. quality.org | 29 7.1.2 People INTERPRETATION In addition to ensuring the competence of its own people, the organisation must ensure that external experts brought in to provide any assistance with the FSMS are themselves competent. Evidence of this must be documented, including any agreements or contracts involved. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals should ensure that the different competences needed for the effective operation of the FSMS are identified and fulfilled. They can be involved in drawing up job descriptions which include qualification requirements as well as interviewing key recruits to the defined roles. Food safety professionals have a vital role to play in selecting and managing external experts to advise or work on aspects of the FSMS. They are likely to work alongside such experts or manage their contributions, as well as informing top management on the progress of any projects. Implications for audit professionals Since the employment of competent personnel is a key foundation of the FSMS, audit professionals need to ensure that the processes for identifying competence needs and fulfilling these needs are consistently implemented. This includes the processes used to contract with external experts who may impact the FSMS. 30 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 7.1.3 Infrastructure INTERPRETATION The requirement for suitable infrastructure for the effective implementation of the FSMS is again emphasised with an additional requirement for the determination of infrastructure needs as well as the necessary resources to allow its establishment and maintenance. New notes underline the wide coverage of such infrastructure to include property, utility services, equipment, software, transport and IT. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals place high importance on adequate infrastructure being in place to assure food safety. They could now be expected to contribute to the identification of infrastructure needs and report to management on the level of resources needed. Food safety professionals may need to add to their skillset to be able to deal with issues such as the software products and IT technology used in the FSMS in addition to the physical aspects. Implications for audit professionals Many of the infrastructure needs for food safety are specified in regulations which auditors will need to take into account. Others relate to prerequisite programmes which the FSMS may need to incorporate as set out in the relevant technical specification, ISO/TS 22002 (all parts). In addition, auditors will use their sector knowledge to evaluate whether the appropriate infrastructure needs have been determined. The use of information technology in both the management and operations of the organisation may present an additional challenge to auditors’ skills. quality.org | 31 “The standard does not require organisations to keep change planning considerations in documented form” 7.1.4 Work environment INTERPRETATION The work environment – as distinct from infrastructure – is likely subject to requirements set by regulations to assure food safety. The accompanying notes identify these as being human and physical factors which may be social, psychological and physical, and which will differ depending on the products and processes involved. There is an additional requirement for the determination of work environment needs as well as the necessary resources to allow the establishment and maintenance of the environment. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals should be very familiar with the work environment that needs to be in place to assure food safety. They could now be expected to contribute to the identification of work environment needs and report to management on the level of resources needed. Food safety professionals may need to add to their skillset to be able to deal with issues such as social and psychological factors in addition to the physical aspects. Implications for audit professionals Many of the work environment needs for food safety are specified in regulations which auditors will need to take into account. Others relate to prerequisite programmes which the FSMS may need to incorporate, as specified in ISO/TS 22002 (all parts). In addition, auditors will use their sector knowledge to evaluate whether the appropriate work environment needs have been determined. The inclusion of social and psychological factors in the work environment of the organisation may present an additional challenge to auditors’ skills. 32 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 7.1.5 Externally developed elements of the food safety management system INTERPRETATION This new requirement recognises that some organisations may wish to bring in outside help to contribute to some elements of the FSMS, e.g. PRPs, hazard analysis and hazard control plans. In this case, the organisation needs to ensure that such elements conform to the standard and correctly apply to the products, processes and site operations of the organisation. The work done must have the oversight of the food safety team to ensure that it fits in with the organisation’s products and processes. Such work should become part of the FSMS in terms of implementation and maintenance, in accordance with the requirements of the standard. It should also be retained in documented form. Implications for food safety professionals Elements of the FSMS may need to be developed by external resources due to the need for specialist input, e.g. microbiological, chemical or consultancy services. In this case, food safety professionals can coordinate such input to ensure compatibility with the organisation’s products and processes. On completion of the work, food safety professionals may take over responsibility for the maintenance and updating of these elements. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals need to evaluate the processes used to assign and manage the contributions of externally developed elements of the FSMS in the same way as they would review any other part of the system. They may review this work on a project-by-project basis and should evaluate the effect of the work on the FSMS overall, including the involvement of the food safety team. The general principle is that external contributions are to be handled in a way that allows the integrity of the FSMS to be maintained at the same level as with internally developed contributions. This should be the auditor’s focus. quality.org | 33 7.1.6 Control of externally provided processes, products or services INTERPRETATION This new requirement adopts a similar principle to that in 7.1.5, so that the outsourcing of processes, products and services is managed in such a way that the integrity of the FSMS is maintained. This means that suppliers and subcontractors should be subject to defined standards for their evaluation, selection, monitoring and re-evaluation. In other words, a consistent procurement process needs to be implemented from a food safety perspective. The purpose of this disciplined approach is to ensure sufficient control by the organisation of outsourced elements coming into the FSMS. The organisation has a duty to adequately communicate its needs and retain documentation of the whole process, including any actions taken as a result. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can use their expertise to contribute to management of the procurement of outsourced elements provided by external resources. In this case, food safety professionals can provide technical advice to ensure compatibility with the organisation’s FSMS processes. They should contribute to the evaluation and selection of suppliers and subcontractors from a food safety perspective and participate in decisions on any actions taken. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals should evaluate the whole procurement process employed to obtain products, processes or services relating to food safety from external sources. This includes the necessary management input and contributions of the food safety team. The documentation to be retained should provide a valuable source of evidence for review. 34 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 7.2 Competence INTERPRETATION This clause is designed to ensure that both staff and external providers are knowledgeable of the hazards and risks to food safety associated with their working environment, and possess the competence to ensure an effective FSMS. The organisation must determine the competence requirements for all personnel who affect, or could affect, food safety performance. Once these competence requirements have been determined, the organisation must then ensure that those personnel possess the necessary competence, on the basis of the appropriate combination of education, training or experience. The standard singles out the food safety team which, as a whole, must have the multi-disciplinary competences required. If those competences do not exist, the organisation is required to take action (e.g. remedial training, recruitment or the use of external people) in order to acquire the necessary competence. The effectiveness of the actions taken in raising competence to the required level needs to be evaluated. Organisations need to maintain and retain documented information as evidence of competence. Implications for food safety professionals Competence is defined as the “ability to apply knowledge and skills to achieve intended results”. Training is one of the ways organisations can achieve the necessary competence. Food safety professionals can contribute their knowledge to the training of others. Food safety professionals can assist the organisation in determining the competence necessary for each role. In many countries, the law requires that food safety training be provided to relevant staff involved in handling food products. quality.org | 35 “Food safety professionals can assist the organisation in planning systematic activities to ensure a good level of awareness of food safety among all personnel” Implications for audit professionals Auditors should verify whether organisations have determined the necessary competence with regard to food safety for each role, and assess how they can ensure that competence requirements have been met. Simply recording staff training may not be sufficient to demonstrate competence as defined in the standard. The effectiveness of the training must be demonstrated. Problems with competence often show up in other parts of the system e.g. internal audit, nonconformities and emergency situations. Another key issue that auditors need to verify is whether or not competence is kept up-to-date. If it is not, then knowledge, skills, and behaviours can become outdated due to changes in the organisation, technology or processes. 7.3 Awareness INTERPRETATION Awareness is knowledge-based and there are explicit requirements for people performing work under the organisation’s control to be aware of its food safety policy, any food safety objectives that are relevant to them, how they are contributing to the effectiveness of the FSMS and the implications of not conforming to food safety requirements. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can assist the organisation in planning systematic activities to ensure a good level of awareness of food safety among all personnel – managerial and non-managerial – and among interested parties such as visitors. Regular training activities conducted by food safety professionals can help to ensure that awareness of food safety issues is maintained at an acceptable level. Implications for audit professionals Auditors will have to conduct interviews with personnel at all levels to verify whether food safety awareness is at an acceptable level. Note that the standard does not require records of awareness training to be kept, although in some countries this is a legal requirement. 36 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 7.4 Communication INTERPRETATION This requirement is similar to the 2005 version and encompasses all internal and external communication relating to an FSMS. Organisations need to develop and implement a process to determine those matters relating to the management system on which it wishes to communicate, the timing of such communications, their target audience and the method of delivery. The standard specifies the extent of external communication needed in relation to food safety.This includes external providers, customers, consumers, statutory authorities and any other organisations that are relevant to the FSMS. The process has to ensure that: » all external communications are handled by designated personnel » appropriate communication is an input to management review and updating of the FSMS » documented information is retained as evidence of communications, as appropriate Internal communication processes must cover changes to a range of issues across the FSMS including raw materials, products, processes, equipment, infrastructure, legal requirements, cleaning programmes, technology, competences and any other changes which can impact food safety. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals have a key role to play in the quality of communication, by making sure that it is reliable, consistent, transparent, appropriate, complete, factual, accurate, able to be trusted, and understandable to interested parties.They can advise on what needs to be communicated both internally and externally as well as deal with updating needs and providing communication input to the management review. Implications for audit professionals Auditors should ensure that the organisation has identified external and internal communications that need to take place in respect of the operation of its FSMS and that appropriate documented evidence is retained of these communications. Although documentary evidence should be available, auditors should also conduct interviews with key personnel to determine the effectiveness of communications in the FSMS. Auditors should be aware that key factors in an effective communication process are: » the quality of the information » the methods used for communication quality.org | 37 7.5 Documented information INTERPRETATION Mandatory documents include the documented information required in ISO 22000 and additional information identified by organisations as necessary for the effective operation of their FSMS. Note that there is no requirement for “documented procedures” in the standard, but “documented information” includes documentation of processes as well as records in the FSMS. The extent of documented information can differ between organisations due to their size, complexity and the competence level of personnel. The document control requirements common to other management systems apply, i.e. when documented information is created or updated, the organisation must ensure that it is appropriately identified and described (for example by the title, date, author or reference number).The format of information (e.g. the language, software version and graphics) should be appropriate, and it should be delivered on an appropriate medium (e.g. paper or electronic). Documented information must be reviewed and approved for suitability and adequacy. Organisations are required to control documented information in order to ensure that it is available where needed and is suitable for use. It must also be adequately protected against improper use, loss of integrity and loss of confidentiality. Organisations must determine how they will: » distribute, access, retrieve and use documented information » store and preserve documented information » control any changes to the documented information » retain and dispose of documented information Organisations are also required to identify any documented information of external origin that they consider necessary for the planning and operation of their food safety management systems. Such documentation must be identified and controlled. Note that there is no requirement for documented information to be maintained or retained for the document control process itself, unless the organisation deems it necessary. 38 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “Food safety professionals can assist top management in determining which documented information would be beneficial in the FSMS” Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can assist top management in determining which documented information would be beneficial in the FSMS, in addition to the mandatory documentation specified throughout the standard, which is summarised in Appendix A. This may be used for different purposes, e.g. accountability, consistency, training or transparency. Where organisations choose to hold their documented information in electronic forms, there may be a need to establish access controls (i.e. user logins and passwords) and authorisation levels in order to ensure controls are appropriate. Organisations will need to consider how such systems are to be protected in the event that IT systems break down, and how access to the documented information can be preserved if IT systems are unavailable. They will also be required to demonstrate how the integrity of their documented information is maintained. This involves issues of cybersecurity, backup systems, technology settings etc. Implications for audit professionals Auditors will have to audit without relying on documented procedures when gathering evidence. They will need to use interview and observation skills more often to obtain evidence. Auditors will increasingly access and use electronic systems in order to evidence how organisations control their documented information. This could require additional competences in the technologies employed. 8 Operation This section focuses on management and control of the operational processes of the FSMS conducted by the organisation for the purpose of establishing and maintaining food safety. It specifies comprehensive methods for dealing with food safety hazards and the controls necessary for effective food safety within the context of an FSMS. quality.org | 39 8.1 Operational planning and control INTERPRETATION Organisations need to plan, implement and control their operational processes, including outsourced processes, by establishing operating criteria and implementing control of the processes in accordance with these operating criteria. Organisations need to maintain and retain documented information to the extent necessary to have confidence that the processes will be carried out as planned. In other words, the organisation decides which documented information on the operational processes will be under the control of the FSMS. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can help the organisation to clearly define the degree of control needed for internal and outsourced processes. They can help with establishing the associated operating criteria, advise on the effects of planned changes, review the consequences of unplanned changes and provide input into any subsequent decisions by management. Implications for audit professionals Since activities and processes conducted by the organisation, its suppliers and subcontractors are covered by the organisation’s FSMS, they are subject to internal audit and, possibly, external audit. Auditors may use risk-based criteria to decide which ones need to be audited more frequently, especially those internal processes, contractors or outsourced processes that deal with high-risk hazards. 40 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 8.2 Prerequisite programmes (PRPs) INTERPRETATION The requirement to establish prerequisite programmes (PRPs) is similar to the previous 2005 version of the standard, with the added requirement for the guidance in all parts of the technical specification ISO/TS 22002 to be considered along with other codes. PRPs must also be updated when appropriate. They can apply to products, processes or the work environment. Appropriate PRPs may be implemented either across the production system or for specific products or processes, and approved by the food safety team. A range of issues needs to be considered when selecting PRPs, including receipt of raw materials, products, processes, equipment, infrastructure, legal requirements, cleaning programmes, support services and any other factors that can affect food safety. PRPs need to be monitored and verified as effective for the prevention or reduction of contaminants wherever they may occur. Documentation associated with the selection, establishment, monitoring and verification of the programmes must be retained. Implications for food safety professionals The input of food safety professionals is vital to the implementation of PRPs in the FSMS.They can bring their expertise to bear on the types of programmes needed, the work practices to follow and the methods for effective monitoring and verification. Given the wide range of PRPs likely to be needed, food safety professionals can use their knowledge and skills to assist in selecting programmes and in selecting external suppliers and providers of services such as laboratory testing, pest control, transportation and storage. They should also be aware of changes to legal requirements which may have an impact on PRPs. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals must allow sufficient time in audit plans for evaluation of the PRPs implemented in the FSMS. Their knowledge will need to encompass the guidance in all parts of ISO/TS 22002 as well as the latest codes of practice. This evaluation needs to include the reasoning behind the selection of PRPs and their monitoring and verification. The food chain sector-specific knowledge of audit professionals will be of increased importance in determining the adequacy of PRPs. Good awareness of sources of contamination associated with products, processes and services, whether internal or external, will be essential. quality.org | 41 “The requirement to maintain and retain documentation of the traceability system should assist audit professionals with their evaluation of its integrity” 8.3 Traceability system INTERPRETATION Traceability of materials and products through the food chain is an established feature of food safety management systems. The requirements have been strengthened to include, as a minimum, the consideration of factors such as tracking materials, ingredients and intermediate products to the end products, reworking processes, end product distribution and compliance with legal requirements. For the traceability system to be effective, documentation needs to be retained and maintained for a predefined period of – at least – the shelf life of the associated product. A new requirement is the need to verify and test the effectiveness of the traceability system in the FSMS. In this context, reconciliation of quantities of inputs to output products is expected to be demonstrated. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals should be familiar with the elements of a traceability system which can identify and track materials, ingredients and products through the organisation’s processes. They can provide practical advice for dealing with traceability of batches and lots of materials in whatever form they exist, e.g. powder, liquids, solids etc., including the required documentation. Food safety professionals should be able to set up and maintain the new verification and test regimes necessary to demonstrate the effectiveness of the traceability system. Implications for audit professionals The requirement to maintain and retain documentation of the traceability system should assist audit professionals with their evaluation of its integrity. They should verify the effectiveness of the system itself as well as reviewing the methodology employed to reconcile inputs with outputs to demonstrate that it is reliable. 42 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 8.4 Emergency preparedness and response INTERPRETATION The standard requires the organisation to establish, implement and maintain processes to prepare for emergency situations and to respond if they occur, in order to protect food safety. The emergency situations to be covered may originate inside or outside the organisation and have the potential to affect the food safety management system, including breach of legal requirements. Organisations have to ensure that emergency plans are ready to be triggered and that they have the capability to respond effectively to emergency situations and incidents to mitigate the impact on food safety. In order to do so, the planned response actions need to be tested, reviewed and revised if necessary, in particular after the occurrence of actual emergency situations and after tests. Interested parties need to be made aware of these arrangements (and when necessary, trained) if they are required to participate in the emergency response, or if they may be affected by the emergency situation. Personnel, in particular, should be informed of their duties and responsibilities in emergency situations. Organisations need to maintain and retain documented information on their emergency response processes and plans. This may include response procedures, data to be communicated, test results, training records and improvement action plans. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can deploy their expertise not only in developing processes and plans, but also in communicating them to all parties potentially involved in emergencies, and testing them in drills. They can take a lead in emergency responses, keeping people informed, providing any necessary training, generating the required documented information and finally, keeping all involved parties updated and alert. The emergency preparedness and response processes may include the training of emergency teams, a list of key personnel and aid organisations, contact details of key interested parties, evacuation routes and assembly points, and the possibility of assistance from neighbouring organisations. quality.org | 43 Implications for audit professionals Unless emergency response tests are being conducted at the time of audit, auditors will have to rely on interviews and documentation to verify conformity with this requirement. Audit trails could easily follow the PDCA cycle as applied to emergency response processes. The focus of the audit professional should be the potential impacts on food safety and their mitigation. Note that every discrepancy found during the audit of the emergency plans or any incident which occurred during an emergency or drill has to be considered as a nonconformity in the system, and appropriate corrective actions have to be taken in order to prevent its recurrence. 8.5 Hazard control As with the previous 2005 version, the core of the standard is a comprehensive set of requirements for the identification, analysis and, if necessary, control and monitoring of food safety hazards which may not be dealt with by the PRPs. These are based around the principles of HACCP and additional control measures which first appeared in the 2005 version. Changes have been made that clarify and strengthen the application of controls throughout the hazard control process. 44 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 8.5.1 Preliminary steps to enable hazard analysis INTERPRETATION The standard again emphasises that, in order to conduct a reliable hazard analysis, information needs to be gathered about the regulations, products and processes which relate to the food safety hazards faced by the organisation. This is the responsibility of the food safety team who need to maintain and retain relevant documentation. Comprehensive data needs to be accessed relating to the characteristics of raw materials, ingredients and packaging as well as those of the end products. Information about the source of the item, e.g. animal, vegetable or mineral, now has to be sought and the data has to be kept up-to-date. Data gathered must include the intended use of the product and must specifically identify consumer groups. It must including those groups who may be vulnerable to hazards such as allergens. The food safety team must create sufficiently detailed flow diagrams, including associated processes such as product packaging or process categories with which to conduct the hazard analysis. This documentation must be verified onsite for accuracy and kept up-to-date. As well as the organisation’s processes, the food safety team must document the work environment and facilities surrounding them. This requires more detail than previously, including layout, equipment, seasonal issues, PRPs and any other controls as well as external factors that might influence the measures to be decided. Implications for food safety professionals The work required to satisfy this requirement is likely to be considerable, but should be routine for food safety professionals. A great deal of documented information will be produced, which has to be maintained. This will challenge the administration skills of food safety professionals. The data gathered at this stage of the hazard control process plays a vital part in the determination of controls for food safety. The knowledge and expertise of food safety professionals at this stage should provide an essential contribution to the subsequent hazard analysis process. quality.org | 45 Implications for audit professionals Although the documentation available to audit professionals to work through may be considerable, they can use effective sampling techniques to determine the rigour with which the required information was obtained. Audit professionals need to ensure that this information is both comprehensive and accurate in order for it to provide a sure foundation for the hazard analysis. 8.5.2 Hazard analysis INTERPRETATION Using the prior research, the food safety team are responsible for the identification of all possible food safety hazards at all stages and the determination of their acceptability in the end product. From this deliberation, the need for control measures at any stage can be determined. The scope of this work is very similar to that in the previous 2005 version of the standard, with minor amendments for clarification. An assessment of the identified hazards has to be carried out. Note that this is the organisation’s responsibility, not necessarily that of the food safety team. There is a new requirement to allocate significance to a hazard based on the likelihood of its occurrence in the end product and the severity of any adverse health effects. This is a similar risk assessment technique to that found in other management system standards. Not only the outcome but the methodology used for this assessment has to be documented. From the hazard assessment, the need for control measures needs to be determined using a systematic basis. These can be managed at two levels, as OPRPs (operational prerequisite programmes) or CCPs (critical control points). The control measures themselves should be subject to a risk assessment of their failure based on the likelihood of failure and the severity of any consequences. The control measures also need to be assessed for the feasibility of establishing CCPs or, for OPRPs, action criteria. This is a new requirement which specifies criteria for the monitoring of OPRPs. The management of OPRPs has been brought more into line with the process for managing CCPs. The feasibility of monitoring CCPs or OPRPs and taking timely action on failure to meet the specified criteria also has to be assessed. The methodologies used in conducting these assessments along with the resulting outcomes have to be maintained in documented form. This should include any external requirements such as regulations or customer specifications which may influence the decisions on control measures. 46 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “A decision on the level of control measures needed for identified hazards is a key feature of the whole process” Implications for food safety professionals The expertise of food safety professionals can be employed to ensure the accurate identification of hazards. They should know what they are, where they are found, their likely impact and the need for their control. Although the food safety team is not specifically tasked with the hazard assessment itself, food safety professionals can contribute their knowledge and skills to this important exercise, including the allocation of significance. A decision on the level of control measures needed for identified hazards is a key feature of the whole process. Whether internal or external, food safety professionals can bring their sector-specific knowledge to bear on the methodology to be employed in the determination of controls and the acceptance criteria to be used. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals are charged with the responsibility to evaluate the identification and assessment methodologies employed for the food safety hazards and their control at all stages. They should be very familiar with the microbiological, chemical and physical characteristics of those hazards relevant to the part of the food chain and processes being audited. Audit professionals should resist conducting their own hazard identification and assessment process for comparison purposes, but rather assess whether the results of the methodologies employed were complete and reliable. They should evaluate whether the controls and associated criteria selected will successfully eliminate or reduce the hazard to a level acceptable to the organisation. 8.5.3 Validation of control measure(s) and combinations of control measures INTERPRETATION Once control measures are determined, a validation exercise is required to ensure their effectiveness. This requirement is similar to that in the 2005 version, with the addition that the validation methodology needs to be documented along with documented evidence of the capability of the control measure or combination of controls involved. Note that the food safety team is now responsible for validation. The methodology needs to include a process for the modification and reassessment of the control measure by the food safety team in the event of the failure of the control measure in the validation process. quality.org | 47 Implications for food safety professionals Whether internal or external, food safety professionals should be able to advise on the process necessary to validate the relevant control measure or combination of measures stated in the hazard control plan. Their expertise can contribute to the improvements necessary in the event that the control measure is found to be deficient as a result of the validation process. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals should review the methodology used for validation exercises and assess the outcomes of the testing of the control measures. They should make use of their knowledge of the relevant sector of the food chain to evaluate whether the final control criteria specified are reasonable and consistent with industry practice. 8.5.4 Hazard control plan (HACCP/OPRP plan) INTERPRETATION Although this is a new requirement, it replaces the original requirement for a HACCP plan by requiring the plan to incorporate both CCPs and OPRPs. This standardises the practice already employed by many organisations under the 2005 version of the standard. It aligns the management of OPRPs and CCPs into one document with the same information for a control measure to be applied to each. The hazard control plan must be implemented. The hazard control plan will identify the existence of OPRPs and CCPs in the FSMS, allied to the respective hazard. The rationale behind the decision on which control measure to include should be documented. The critical limits associated with CCPs must be measurable but the action criteria for OPRPs may be either measurable or observable. Both control measures should be monitored but there is an implication that monitoring and measurement of critical limits for CCPs should be treated more rigorously as befits the more serious consequences of their failure. Note that monitoring of OPRPs by observation should be supported by documented instructions. Upon detected failure to meet critical limits, the plan should specify the actions to be taken when the system nonconformity process is triggered. This should involve both correction (addressing the nonconformity) and corrective action (addressing its cause) being taken, and should result in the safeguarding of potentially unsafe food. 48 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard Implications for food safety professionals Production of a HACCP plan should have been a reasonably straightforward task for food safety professionals, so compilation of a hazard control plan with the additional content should not represent too much of a challenge. The bigger challenge may be the decision on whether an OPRP or a CCP is the correct control measure to be documented in the plan along with the determination of critical limits or action criteria for each control measure. The hazard control plan should be kept updated and food safety professionals can provide the necessary input when changes are made to products and processes which trigger a reassessment of hazard controls. Monitoring operations for the control measures are very important, and food safety professionals can contribute their expertise to the decisions on monitoring frequency, calibration of measuring equipment, inspection instructions and evaluation of results. Implications for audit professionals The hazard control plan is one of the key documents that audit professionals should access when auditing the FSMS. It can provide an audit trail back to the processes which resulted in the plan, and a trail forward to the end product and related processes. These trails can embrace methodologies, competences and maintenance of documentation in addition to gathering evidence of food safety activities through observation. Failure of the monitoring process can lead to serious food safety issues due to the potential existence of undetected nonconformities, so audit professionals should ensure that this aspect is thoroughly reviewed. As well as verifying the methodologies employed, they should evaluate the nonconformity management process for its effectiveness in dealing with failure to meet criteria limits. quality.org | 49 8.6 Updating the information specifying the PRPs and the hazard control plan INTERPRETATION This clause essentially repeats the requirements for keeping key documents up-to-date, including the hazard control plan and the documented processes contributing to it. It reminds users that the system is dynamic and must reflect changes to products, processes and systems which can affect food safety. Implications for food safety professionals Part of the responsibility of food safety professionals is to have good awareness of forthcoming changes that can impact the FSMS. They should be proactive in preparing the system for these changes so that updating can take place with the minimum of disturbance. A robust document control process will be essential to meet this requirement. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals should be well aware of the importance of keeping information up-to-date. As well as reviewing the change control systems, they should use their sector-specific knowledge of changes to legislation, technological developments etc. to determine whether organisations have reliable processes in place to gather information about changes in a timely manner. 8.7 Control of monitoring and measuring INTERPRETATION This requirement addresses the need for known accuracy limits when monitoring or measuring activities are undertaken. It is similar to that in the 2005 version, with additional emphasis on the validation of software products used in the FSMS. Documented calibration results are required, traceable to national or international standards where they exist. Changes and updates to software programmes should be validated before implementation with the associated documentation being retained. Note that unmodified off-the-shelf commercial software is considered to be already validated. 50 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “Auditors should take steps to familiarise themselves with the functions and parameters associated with the software in preparing for the audit” Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals should be well aware of calibration processes for measuring and monitoring equipment. They can advise on calibration frequency, accuracy limits and standards traceability. With the reliance on software, particularly due to the increasing use of robotics and automation, food safety professionals may need to ensure that their knowledge of information technology and related validation techniques is at the correct level. Implications for audit professionals Experienced audit professionals should be very familiar with the processes surrounding the calibration of devices used for monitoring and measurement in a management system. They may not be so familiar with the routines used for testing software functions when validating its use. In this case, auditors should take steps to familiarise themselves with the functions and parameters associated with the software in preparing for the audit. 8.8 Verification related to PRPs and the hazard control plan INTERPRETATION This clause is similar to the clause on verification planning in the 2005 version, with an additional requirement that those conducting verification activities should be independent of those responsible for monitoring or measuring. Verification planning should be carried out, but there is no requirement for this process to be documented other than recording the results of verification activities. Verification outcomes should be analysed as part of the performance evaluation of the FSMS. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals working in an FSMS environment should be managing or conducting verification activities on an ongoing basis as a routine part of the system checks. They can advise on the extent of verification activities and their frequency. Should the verification results indicate problems, they can assist with the decisions on corrective action. Implications for audit professionals Although verification results should be available in documented form, audit professionals will need to interview relevant personnel to determine the extent of verification planning in the FSMS. They need to confirm whether such planning is consistent and ongoing and whether verification personnel are competent and independent. They should also verify that verification results contribute to the performance analysis of the FSMS. quality.org | 51 8.9 Control of product and process nonconformities INTERPRETATION This clause primarily relates to the handling of nonconformities associated with OPRPs and CCPs, although it also applies to product and process nonconformity in general. A new requirement is for monitoring of OPRPs and CCPs to be carried out by designated, competent personnel who can initiate the correction and corrective action processes. The nonconformity management methodology should be documented, and should cover the identification, assessment and corrections necessary for proper handling in addition to a review of the corrections taken. The process must include identification of affected products and processes, the cause of failure and the resulting food safety consequences. Corrective actions which address the root cause of the nonconformity must be considered and, if appropriate, initiated to prevent recurrence. Actions should include a trend analysis of monitoring results and nonconformities raised by external parties such as customers, consumers and regulatory authorities. Documentation relating to corrective actions should be retained. It is important that potentially unsafe food products do not enter the food chain. Accordingly, such products need to be handled in a controlled way which must be documented. Products already released whose food safety is in doubt should be subject to a documented withdrawal process in conjunction with the external party. The standing of all nonconforming products must be evaluated. Nonconforming products resulting from CCP failure shall not be released, but designated for reprocessing, redirecting for other use or disposed of as waste. Nonconforming products resulting from OPRP failure may be released if their food safety integrity can be proven through monitoring, meeting performance standards or testing and inspection routines. Withdrawal or recall of nonconforming products should be conducted by competent personnel who will notify affected external parties, arrange the removal of such products from the food chain and manage the sequence of activities needed for the process. Incidents of withdrawal or recall should be documented and reported for input to the management review. The effectiveness of the withdrawal or recall process needs to be verified by means such as drills of mock incidents. 52 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals should be well placed to handle the processes needed for dealing with nonconforming products and processes, including withdrawal and recall situations. They would be expected to meet the competence requirements for monitoring of OPRPs and CCPs in addition to determining the steps to be taken when such monitoring identifies nonconformity. Decisions relating to the disposition of nonconforming product can be informed by the expertise of food safety professionals as they conduct evaluation of the nonconformity. They can also contribute to decisions on whether or not to release product which has been designated as nonconforming through an OPRP failure. Since withdrawal or recall of previously released product is a major event, food safety professionals can underpin this decision by providing advice as to its scope, implementation and safe handling. Testing of the withdrawal or recall process could be overseen by food safety professionals who could identify any improvement opportunities. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals should be well aware of the processes needed to handle nonconforming situations as they provide fertile ground for several audit trails. Such situations warrant the attention of audit professionals towards product and process controls, personnel competence, traceability systems, verification processes, decision-making, communication and documentation. Auditors should not only evaluate the effectiveness of nonconforming system processes in dealing with all the consequent issues of food safety, but also on how much the performance of the FSMS itself gains from the improvement opportunities presented. quality.org | 53 9 Performance evaluation of the food safety management system INTERPRETATION While the previous section largely focussed on the monitoring and performance of the hazard control process, this new section addresses the overall performance of the FSMS as a whole. 9.1 Monitoring, measurement, analysis and evaluation INTERPRETATION First, organisations must understand what they need to monitor and measure in order to determine the performance of the FSMS and evaluate its effectiveness (e.g. its progress on food safety objectives, characteristics of activities and operations related to the identified hazards, risks and opportunities, the compliance level of legal requirements, and other requirements). This includes the determination of the criteria against which food safety performance will be evaluated, including appropriate measures. As part of the process, organisations have to determine the methods used for accurate monitoring and measurement with calibrated equipment where appropriate. This ensures that analysis and performance evaluation is based on results that are valid. These methods may include, as appropriate, statistical techniques to be applied to the analysis of those results. In addition, organisations must also determine when monitoring and measurement should be carried out, including when the results of monitoring and measurement should be analysed and evaluated. Organisations have to retain appropriate documented information as evidence of the results of monitoring, measurement, analysis and evaluation, with the results providing input to the management review. 54 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can use their experience to ensure that the extent of planning, monitoring and measuring is consistent with the nature of the processes of the FSMS and is compatible with the associated analysis and evaluation. Food safety professionals can ensure that the results of monitoring and measurement are reliable, reproducible and traceable, in order to generate a consistent set of data that can be analysed, using statistical techniques when appropriate. Implications for audit professionals Auditors need to obtain evidence of analysis and evaluation of data obtained from monitoring and measurement relating to the overall performance of the FSMS. Auditors should have a basic knowledge of the sector-specific processes and of the statistical techniques used by the organisation in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the planned arrangements for the system. quality.org | 55 9.2 Internal audit INTERPRETATION This requirement is very similar to the internal audit requirements of most other management system standards, being based on ISO 19011, as referenced in the associated note. The standard contains the requirement for organisations to carry out internal audits at planned intervals in order to provide information as to whether the FSMS conforms to both the organisation’s own requirements and the requirements of the ISO 22000 standard. Internal audits must also provide information that could be used to determine whether the FSMS is being effectively implemented and maintained. This clause also sets out a series of requirements relating to how audit programmes must be structured, what audits must cover, who should undertake audits and how audits are to be reported. The audit programme needs to reflect the importance of the processes concerned, changes in the organisation, risks and opportunities, and the results of previous audits. Each audit needs to have a defined scope and its own audit criteria. Audits and auditors need to be competent, impartial and objective. This means that internal auditors should not audit processes in which they are or have been involved, either in planning or operationally at a managerial or nonmanagerial level. The findings from audits need to be fed back to both the relevant management and the food safety team. Any required corrections and/or corrective actions must be taken in the timescale agreed with the auditee. Documented information needs to be retained to provide evidence that the audit programme has been implemented. Documented information must also exist to provide evidence of the results of audits. Note that documented procedures for internal audits are no longer required. 56 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “Food safety professionals should note the need to retain documented information evidencing the implementation of an audit programme and the results of audits” Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals would normally be expected to have the competence to conduct internal audits of the FSMS, provided they don’t audit processes and systems in which they have been directly involved. The purpose of internal audits is to provide information on whether the FSMS conforms to the requirements of the standard and any additional requirements determined by the organisation. Food safety professionals should be able to determine this from the conduct of the audit programme. The results of internal audits need to be fed back to “relevant management”, i.e. to those individuals best placed to act on the audit findings. Food safety team members also need to be informed of the relevant results. Food safety professionals should note the need to retain documented information evidencing the implementation of an audit programme and the results of audits. quality.org | 57 “Documented information must also be available to evidence the results of audits” Implications for audit professionals The internal audit process itself must also be audited. Audit professionals should access documented information confirming the implementation of an audit programme by the organisation. Documented information must also be available to evidence the results of audits. Audit professionals can learn a great deal about the effectiveness of the FSMS itself by conducting a thorough audit of its internal audit processes. FSMS audit professionals, or internal auditors, are not expected to conduct legal compliance audits but rather to evaluate whether the FSMS processes are effective in ensuring such compliance by the organisation. Auditors of legal compliance require a slightly different skillset to that of management systems auditors. It should be noted that legal compliance audits are not required by the standard. 58 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 9.3 Management review INTERPRETATION This clause requires reviews of the suitability, adequacy and effectiveness of the FSMS to be undertaken by top management at planned intervals. In other words, top management have to determine, from time to time, the extent to which the FSMS is achieving its intended outcomes. The items that top management must, as a minimum, consider during a management review are actions from previous reviews, changes in the external and internal context, updates in the legal requirements, analysis of verification results, and the results of updates to systems. The reviews should also include information on food safety performance, including trends in: » the achievement of objectives » incidents, nonconformities and corrective actions » results from internal and external audits » results from internal and external inspections Trend analysis is an important function for top management to address because it can reveal whether the outcomes of the FSMS result in safe food for all parties on an ongoing basis. If it is failing in this regard, there are serious implications for the organisation both internally and externally. The management review process should not just look at historical trends but give top management the opportunity to influence the future performance of the FSMS by taking decisions to initiate improvements. They need to address identified weaknesses in the system by making changes, directing strategies for improvement and setting revised high-level food safety objectives. Such decisions need to be documented. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can contribute to the management review by preparing data on the performance of the FSMS during the relevant period since the previous review. They can supplement this work by making recommendations on future actions. quality.org | 59 “Auditors should expect to assess a strategically focused management review of the FSMS” The management review should be high-level, based on the review of key factors which affect the suitability, adequacy and effectiveness of the FSMS. The management review topics need not be addressed all at once. Although not a common methodology, the review may take place incrementally over a period of time and can be part of regularly scheduled management activities, such as board or operational meetings. It does not need to be a separate activity. Some organisations may ask the food safety professional to prepare all of the information needed for this review along with a draft of the conclusions. For such a contribution to have the maximum effectiveness, the information should originate from each relevant manager, the analysis should be closely reviewed and the associated decisions taken by top management. This is another example of the extensive involvement by top management that the standard expects. Implications for audit professionals Auditors should expect to assess a strategically focused management review of the FSMS. Context, risks and opportunities need to be considered, as well as the alignment of food safety to the organisation’s overall strategic objectives. Auditors should not audit this requirement only by conducting an interview with the food safety professional, who typically has all necessary records to show, but is not likely to be the owner of the management review process. Auditors should definitely audit this clause with top management. In order to do so effectively, they must gather evidence, face-to-face with one or more senior managers, on corporate strategy issues relating to the FSMS that go beyond operational issues. Auditors must be competent to be able to audit at a corporate level. 10 Improvement The principle of focusing on improvement is intrinsic to the FSMS in all areas. There is no such thing as a perfect system, but organisations must strive towards achieving the best possible performance of the FSMS at all times. This section specifies the requirements which can help organisations towards this goal. 60 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 10.1 Nonconformity and corrective action INTERPRETATION This clause sets out how organisations are required to act when system nonconformity is identified. In such instances, the organisation is required to take whatever action is necessary to control and correct the nonconformity, and to deal with the consequence. A key requirement is to identify the root cause of the nonconformity and take appropriate action to prevent recurrence. While root cause analysis is being performed, organisations may also have to undertake immediate but temporary actions to prevent the continued occurrence of the same nonconformity. This would be the initial correction part of the overall corrective action. Organisations must also review the effectiveness of corrective actions and, if necessary, make further changes to the FSMS itself. Documented information has to be retained as evidence of the nature of the nonconformities that have occurred and of any corrective action taken, including their effectiveness. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals can use their expertise to determine the root cause of incidents and nonconformities, including whether other similar nonconformities exist (or potentially could exist) elsewhere. They are also best placed to suggest at which level the most effective corrective action lies in the hierarchy of controls. Documented information must be retained not only on the results of the actions taken, but also the nature of the nonconformities, as well as any subsequent actions taken. Implications for audit professionals Auditors should gather evidence of the processes in the FSMS that deal with the initial handling of a nonconformity, including the triggering of emergency response if necessary, the evaluation of the root cause, the implementation of correction and corrective action and the subsequent review of its effectiveness. Audit trails could be based on the PDCA cycle associated with this aspect of the FSMS. Audit professionals should ensure that the required documented information is available covering the entire scope of the nonconformity from detection to review of the effectiveness of corrective action. quality.org | 61 10.2 Update of the food safety management system INTERPRETATION The food safety team is charged with the responsibility for updating the management system, especially with regard to the hazard analysis, hazard control plan and PRPs. Periodic reviews should be undertaken without necessarily waiting for changes which might trigger a review. Reviews should be documented, with the results contributing to the management review process. Implications for food safety professionals Food safety professionals working in an FSMS should keep their fingers on the pulse of the system. Periodic reviews of key elements are one way to achieve this. Note that such reviews are different to internal audits as the purpose of the review is not the determination of conformity but the identification of the need for updating to ensure that the system remains as effective as it should be. Implications for audit professionals Audit professionals should verify that the reviews by the food safety team are sufficiently comprehensive to pick up any weaknesses in the system. Documentation should help with this, but interviewing members of the food safety team can also verify the extent of their involvement in the process. 62 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard “The principle of continual improvement is embodied in most other management systems” 10.3 Continual improvement INTERPRETATION The principle of continual improvement is embodied in most other management systems. It is designed to inculcate an organisational culture and mentality of striving to achieve a better performance out of the FSMS overall by seeking opportunities to improve. Actions which top management might take with a view to achieving continual improvement include: » enhancing food safety performance through meeting objectives » promoting a proactive culture that provides support to the FSMS » promoting the participation of all personnel in the identification and implementation of opportunities for improvement » communicating to personnel the results of the improvement actions taken The FSMS should be geared towards continual improvement and the elements of the system can be used to facilitate this. Implications for food safety professionals The food safety professional can facilitate and lead this process of engendering a focus on improvement. Nevertheless, the participation of top management in conjunction with food safety professionals in the review and decision-taking are key factors for achieving a successful improvement process. quality.org | 63 “Auditors should check whether the organisation has implemented the identified opportunities for improvement” Implications for audit professionals Auditors should be able to track the organisation’s improvement processes throughout the whole FSMS. Auditors should seek evidence that organisations are using the outputs from their analysis and evaluation, internal audit and management review processes to identify improvement opportunities and food safety underperformance. They should also verify that the organisation is using suitable tools and methodologies to support its analysis and reviews. Additionally, auditors should check whether the organisation has implemented the identified opportunities for improvement in a planned and controlled manner and whether the whole workforce, from top management to non-managerial workers, participate in the process. Annexes The standard has two annexes containing four tables which provide cross references between the Codex HACCP principles and the relevant clauses of ISO 22000:2018, the structural differences between the 2005 and 2018 versions of the standard, and the detailed cross references between clause 7 (Support) and clause 8 (Operation). These cross references can assist with the transition to the 2018 version. 64 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 05. Conclusions The revised standard adopts in full the text of Annex SL, with very minor modifications. Therefore, it aligns with ISO 9001 and ISO 14001, with the same structure, same terms and definitions, and same generic text. Organisations will now have a model that integrates food safety into the strategy and decision-making processes at all levels and contributes to their sustainability. Top management will be much more involved in food safety matters and will be challenged to demonstrate their leadership and commitment. Customers and consumers will benefit from enhanced care of their food safety needs due to wider participation of many parties in the development, planning and operation of the FSMS. Food safety professionals will find some change and more involvement in all technical and operational food safety-related issues and will have to be able to interact with top management and to assist top management to discharge their duties and responsibilities. Internal and external FSMS auditors will need adequate time to audit against the revised standards and should consider this in their audit planning. They may need to enhance their knowledge, understanding and skill to audit top management more rigorously. They will need to possess knowledge of corporate working, and to be more aware of business strategies. The publication of the revision to ISO 22000 in 2018 signals the start of a transition period during which those organisations which are already certified to ISO 22000:2005, and wish to transition to the revised standard, will need to make changes to their existing food safety management systems. Note that the transition period, originally set at three years in line with the transition processes for other ISO standards, has been extended by six months, ending 29 December 2021. CQI and IRCA recognise that the revised standard may need considerable support for its introduction. That is why we have committed to supporting our members and certificated auditors, not just through the development stages, but beyond the publication of the revised standard. Whatever your role is in the food safety profession and whatever sector your organisation may operate in, CQI and IRCA will be on hand to provide informed and impartial advice to help you make the transition successfully. quality.org | 65 A. Appendix Summary of required documented information 4.3 Determining the scope of the food safety management system 8.5.2.4.2 Selection and categorisation of control measures 5.2.2 Food safety policy 8.5.3 Validation of control measure(s) and combinations of control measures 6.2.2 FSMS objectives 7.1.2 People 7.1.5 Externally developed elements of the food safety management system 7.1.6 Control of externally provided processes, products or services 7.2 Competence 7.4.2 External communication 8.1 Operational planning and control 8.2 PRPs 8.3 Traceability 8.4 Emergency preparedness and response 8.5.4.1 Hazard control plan 8.5.4.2 Determination of critical limits and action criteria 8.5.4.3 Monitoring systems at CCPs and for OPRPs 8.5.4.5 Implementation of the hazard control plan 8.7 Control of monitoring and measuring 8.8 Verification related to PRPs and the hazard control plan 8.9.2 Corrections 8.9.3 Corrective actions 8.5.1.1 Preliminary steps to enable hazard analysis 8.9.4.1 Handling of potentially unsafe products 8.5.1.2 Characteristics of raw materials, ingredients and product contact materials 8.9.4.2 Evaluation for release 8.5.1.3 Characteristics of end products 8.9.5 Withdrawal/recall 8.5.1.4 Intended use 9.1 Monitoring, measurement, analysis and evaluation 8.5.1.5.2 On-site confirmation of flow diagrams 8.5.1.5.3 Description of processes and process environment 8.5.2.2 Hazard identification and determination of acceptable levels 8.5.2.3 Hazard assessment 66 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard 8.9.4.3 Disposition of nonconforming products 9.2 Internal audit 9.3 Management review 10.1 Nonconformity and corrective action 10.3 Update of the FSMS B. Appendix FSSC 22000 and GFSI The GFSI (Global Food Safety Initiative) benchmarking requirements1 were first created in 2001 by a group of retailers, to try to harmonise food safety standards across the global supply chain. The model relies on certification programme owners (CPOs) meeting the benchmarking requirements and achieving GFSI recognition. Each of the current CPOs offers schemes with obvious similarities (i.e. for food safety in the food chain) though there are some differences in focus. For example, GlobalG.A.P. is focused on agricultural production (extending to some aquaculture) while the Global Aquaculture Alliance is focused specifically on aquaculture. GFSI itself is an initiative of the global Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), which was founded in its current form in 2009, though its origins go back to the middle of the 20th century. The CGF has a membership that includes CEOs and senior management members from many global retail and manufacturing companies.2 The GFSI benchmarking requirements do not constitute a food safety standard in their own right, and food businesses cannot be audited or certified against them. Instead, food businesses need to request audits and certification from certification bodies that offer the various GFSI-recognised schemes (which are managed by the CPOs). Foundation FSSC 22000 is recognised as a CPO by GFSI and is one of around 11 such CPOs – including, as mentioned above, GlobalG.A.P. and the Global Aquaculture Alliance as well as BRCGS, the SQF Institute and others. These organisations offer certification programmes and schemes which certification bodies, in turn, use to audit and certify their clients. 1 https://mygfsi.com/ http://www. meetingmediagroup. com/article/profilethe-consumergoods-forum-cgf 2 https://www. fssc22000.com/ 3 Foundation FSSC 220003 is unique in that it developed its certification programme – the FSSC 22000 scheme – based on the ISO 22000 standard for food safety management systems. It is currently the only GFSI-recognised programme based on ISO 22000 and the associated technical specification for prerequisite programmes (ISO/TS 22002). Foundation FSSC 22000 also offers a scheme for combined FSMS and quality management systems (FSSC 22000 - Quality), which includes the requirements of ISO 9001. quality.org | 67 Acknowledgements CQI and IRCA would like to thank the author, reviewers and contributors for their work on this report. Principal author Ian Dunlop BSc FCQI CQP CQI and IRCA Technical Assessor Reviewers and contributors Erica Colson EMEA Food Sector Propositions Manager, BSI Marta Vaquero Accreditation Specialist - Food and Farm Certification, UKAS 68 | ISO 22000:2018 | Understanding the international standard Sara Walton Sector Lead, Food, BSI Alexander Woods Policy Manager, CQI © 2020 Chartered Quality Institute. All Rights Reserved The Chartered Quality Institute (CQI) The CQI is the chartered body for quality management professionals. It exists to benefit the public by advancing education in, knowledge of and the practice of quality in industry, commerce, the public sector and the voluntary sectors. The International Register of Certificated Auditors (IRCA) IRCA is a division of the CQI and is the leading professional body of management system auditors www.quality.org The Chartered Quality Institute 2nd Floor North, Chancery Exchange, 10 Furnival Street, London, EC4A 1AB Incorporated by Royal Charter and registered as charity number 259678