Microsoft Office 2003 Guida Word Excel Access Powerpoint Outlook Publisher

advertisement

Microsoft® Office 2003

Super Bible eBook

Microsoft® Office 2003

Super Bible eBook

Various Author s

Wiley Publishing, Inc.

Microsoft® Office 2003 Super Bible eBook

Published by

Wiley Publishing, Inc.

10475 Crosspoint Boulevard

Indianapolis, IN 46256

www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2003 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published simultaneously in Canada

Manufactured in the United States of America

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United

States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the

appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978)

646-8700. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475

Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4447, E-Mail: permcoordinator@wiley.com.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: WHILE THE PUBLISHER AND AUTHOR HAVE USED THEIR

BEST EFFORTS IN PREPARING THIS BOOK, THEY MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH

RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK AND SPECIFICALLY

DISCLAIM ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES REPRESENTATIVES OR WRITTEN SALES

MATERIALS. THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR YOUR

SITUATION. YOU SHOULD CONSULT WITH A PROFESSIONAL WHERE APPROPRIATE. NEITHER THE

PUBLISHER NOR AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR ANY LOSS OF PROFIT OR ANY OTHER COMMERCIAL

DAMAGES, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR OTHER

DAMAGES.

For general information on our other products and services or to obtain technical support, please contact our Customer Care

Department within the U.S. at (800) 762-2974, outside the U.S. at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in

electronic books.

Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of Wiley

Publishing, Inc., in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. Microsoft is a registered

trademark of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their

respective owners. Wiley Publishing, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

About the Authors

Peter Kent has been using Microsoft Word for 14 years to write 50 books, scores of

technical manuals, and literally thousands of magazine articles and corporate documents. He

has worked in the software development business for nearly 22 years, designing and testing

software, writing documentation, and training users. He is the author of the widely reviewed

and praised Poor Richard’s Web Site. Today, he is vice president of marketing for Indigio, an

e-services firm. Peter, author of Word 2003 Bible, updated chapters 2, 11 and 18 of the Super

Bible eBook, from the original authors, Brent Heslop and David Angell.

Cary Prague is an internationally known best-selling author and lecturer in the database

industry. He owns Database Creations, Inc., the world’s largest Microsoft Access add-on

company. Its products include a line of financial software: Business! for Microsoft Office, a

mid-range accounting system; POSitively Business! point-of-sale software; the Inventory

Bar code manager for mobile data collection; Check Writer; and General Ledger. Database

Creations also produces a line of developer tools including the appBuilder, an application

generator for Microsoft Access; the EZ Access Developer Tools for building great user

interfaces; appWatcher for maintaining code bases among several developers, and Surgical

Strike, the only Patch Manager for Microsoft Access.

Local and national clients for Database Consulting, LLC, consist of many Fortune 100

companies, including Microsoft, United Technologies, ABB, Smith & Wesson Firearms,

Pratt and Whitney Aircraft, ProHealth, OfficeMax, and Continental Airlines.

Cary is one of the best-selling authors in the computer database management market, having

written more than 40 books that have sold over one million copies. His software topics

include Microsoft Access, Borland (Ashton-Tate) dBASE, Paradox, R:Base, Framework,

and graphics. Cary’s books include various editions of the Access Bible, Access 97 Secrets,

Access Crash Course, dBASE for Windows Handbook, dBASE IV Programming (winner of

the Computer Press Association’s Book of the Year award for Best Software-Specific Book),

and Everyman’s Database Primer Featuring dBASE IV.

Cary is certified in Access as a Microsoft Certified Professional and has passed the MOUS

test in Access and Word. He is a frequent speaker at seminars and conferences around the

country. He is on the exclusive Microsoft Access Insider Advisory Board and makes

frequent trips to Microsoft headquarters in Redmond, Washington.

Cary holds an M.A. in computer science from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and an

M.B.A and Bachelor of Accounting from the University of Connecticut. He is also a

Certified Data Processor. As author of Access 2003 Bible, Carey provided chapters 8, 15,

and 22 to the eBook.

Bill Rodgers is a computing consultant from Newcastle, Australia, with a passion for

V8Supercars and Rugby league and Rugby Union football. Bill specializes in Office and

Windows systems, collaboration, and advanced technologies. Bill has been a contributing

author and technical editor on many Office books for leading international companies and has

been awarded the Microsoft MVP (Most Valuable Professional) award for the past four years

for his support of and expertise with Microsoft products. Bill, contributing author of Office

2003 Bible, wrote chapter 17 of this book.

Curt Simmons, A+, MCSA, MCSE, CTT is a technical trainer and freelance writer. The

author of more than thirty books on various Microsoft and Internet technologies, Curt most

often writes about Microsoft Office products and operating systems. He also teaches several

digital photography courses. Curt’s most recent books include Windows XP Networking

Inside Out, The A+ Technician’s On-the-Job Guide to Networking, iPhoto For Dummies, and

How To Do Everything with Photoshop Album. Curt lives in Saint Jo, Texas with his wife and

children. Visit Curt on the Internet at www.curtsimmons.com. Curt, author of FrontPage

2003 Bible, is responsible for chapters 7, 14, and 23 of this book.

Rob Tidrow is a writer, Web site designer, trainer, and president of Tidrow Communications,

Inc., a firm specializing in content creation and delivery. Rob has authored or co-authored

over 30 books on a wide variety of computer topics, including Microsoft Windows, Microsoft

Office, and Microsoft Internet Information Server. He is the Technology Coordinator for

Union School Corporation, Modoc, IN and lives in Milton, IN with his wife Tammy and their

two sons, Adam and Wesley. You can reach him on the Internet at

rtidrow@infocom.com. Author of the Outlook 2003 Bible, Rob is the author of chapter

10 of this book. Contributing author of the Outlook 2003 Bible, Jim Boyce wrote chapters 3

and 19 of this book.

John Walkenbach is the author of approximately three dozen spreadsheet books. Visit his

Web site at http://.j-walk.com. John, as author of Excel 2003 Bible, wrote chapters 4,

12, and 20 of this book.

Faithe Wempen, M.A., is an A+ Certified hardware guru, Microsoft Office Specialist Master

Instructor, and software consultant with over 70 computer books to her credit. When she is

not writing, she teaches Microsoft Office classes in the Computer Technology department at

Indiana University/Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI), does private computer training

and support consulting, and is the business manager of Sycamore Knoll Bed and Breakfast in

Noblesville, Indiana (www.sycamoreknoll.com). Faithe is a contributing editor at

CertCities.com, and a frequent contributor to CertCities.com, TechProGuild.com, and several

magazines. She teaches online classes for the Hewlett-Packard Learning Center, and serves

on the advisory board for the Computer Technician program at Training, Inc. in Indianapolis.

As author of PowerPoint 2003 Bible, Faithe wrote chapters 5, 13, and 21 of this book.

Edward Willett is the author of more than 20 books, ranging from computer books on a

variety of topics to children’s nonfiction to young adult science fiction and fantasy. A former

newspaper reporter and editor, he writes a science column for newspapers and radio and hosts

a weekly TV phone-in show about computers and the Internet. He’s also a professional actor

and singer. Ed lives in Regina, Saskatchewan, with his wife and daughter. Ed, as lead author

of Office 2003 Bible, wrote chapters 9 and 16 of this book.

Credits

Vice President & Executive Group

Publisher

Richard Swadley

Vice President and Executive Publisher

Bob Ipsen

Vice President and Publisher

Joseph B. Wikert

Executive Editorial Director

Mary Bednarek

Editorial Manager

Mary Beth Wakefield

Development Editor

Ami Frank Sullivan

Special Help

Brian Herrmann

Senior Permissions Editor

Carmen Krikorian

Composition Services

Lowell K. Heusel, Abshier House

Proofreading

TECHBOOKS Production Services

Contents at a Glance

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Part I: Getting Functional with Microsoft Office 2003 ....................... 1

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Microsoft Office 2003 Super Bible eBook .............................. 3

Chapter 2: Paragraph Formatting in Word ................................................................................ 7

Chapter 3: Configuring Outlook 2003 .................................................................................... 53

Chapter 4: Essential Excel Worksheet Operations ................................................................. 81

Chapter 5: Developing Your PowerPoint Action Plan ......................................................... 101

Chapter 6: Introducing Publisher .......................................................................................... 119

Chapter 7: Building FrontPage Web Sites ............................................................................ 137

Chapter 8: Understanding and Creating Access Reports ...................................................... 167

Part II: Collaborating and Integrating

with Microsoft Office 2003 ...................................................... 225

Chapter 9: Building Integrated Documents .......................................................................... 227

Chapter 10: Integrating Outlook with Other Applications ................................................... 241

Chapter 11: Comments and Reviewing Functions in Word ................................................. 257

Chapter 12: Sharing Excel Data with Other Applications .................................................... 279

Chapter 13: Team Collaboration on a Draft PowerPoint Presentation ................................. 295

Chapter 14: Integrating FrontPage with Office Applications ............................................... 317

Chapter 15: Exchanging Access Data with Office Applications .......................................... 353

Chapter 16: Collaborating on a Network .............................................................................. 373

Chapter 17: Windows SharePoint Services with Office System .......................................... 393

Part III: Beyond Mastery: Initiative within Office ........................... 429

Chapter 18: Getting Organized with Outlines and Master Documents ................................ 431

Chapter 19: Processing Outlook Messages Automatically ................................................... 451

Chapter 20: Analyzing Data with Pivot Tables in Excel ...................................................... 469

Chapter 21: Designing User-Interactive PowerPoint Presentations ..................................... 491

Chapter 22: Adding Security to Access Applications .......................................................... 515

Chapter 23: Adding FrontPage Web Components ................................................................ 559

Chapter 24: Advanced Publisher Techniques ....................................................................... 589

Contents

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Part I: Getting Functional with Microsoft Office 2003 .............. 1

Chapter 1: Introduction to the Microsoft Office 2003 Super Bible eBook ... 3

Who Should Read This Book ..................................................................................................... 3

How This Book Is Organized ..................................................................................................... 4

Part I: Getting Functional with Office 2003 ........................................................................ 4

Part II: Collaborating and Integrating with Office 2003 ..................................................... 4

Part III: Beyond Mastery: Initiative within Office .............................................................. 4

Of Special Note for the eBook .................................................................................................... 4

Using the companion Web site ............................................................................................ 5

Conventions Used in This Book ................................................................................................. 5

Chapter 2: Paragraph Formatting in Word ................................................... 7

Applying Paragraph Formatting ................................................................................................. 7

Checking paragraph formats ................................................................................................ 8

Duplicating paragraph formats ............................................................................................ 9

Removing paragraph formats ............................................................................................ 10

Using line breaks ............................................................................................................... 11

Aligning Paragraphs ................................................................................................................. 12

Click and Type: Inserting Paragraphs ....................................................................................... 13

Adjusting Line and Paragraph Spacing .................................................................................... 14

Adjusting paragraph spacing ............................................................................................. 14

Adjusting line spacing ....................................................................................................... 15

Setting Tabs ............................................................................................................................... 17

Setting tabs using the ruler ................................................................................................ 19

Changing or clearing a tab stop using the ruler ................................................................. 20

Setting tabs using the Tabs dialog box .............................................................................. 20

Changing and clearing tabs using the Tabs dialog box ..................................................... 21

Changing the default tab stops .......................................................................................... 22

Setting Indents .......................................................................................................................... 22

Setting indents using the Formatting toolbar .................................................................... 23

Setting indents using the ruler ........................................................................................... 24

Setting indents using keyboard shortcuts .......................................................................... 25

Setting indents using the Paragraph dialog box ................................................................ 25

Bordering and Shading Paragraphs and Pages ......................................................................... 27

Adding borders using the Borders toolbar ........................................................................ 28

Adding borders using the Borders and Shading dialog box .............................................. 29

Spacing between text and border ....................................................................................... 31

x

Contents

Placing borders around individual lines ............................................................................ 31

Fitting a border within margins ......................................................................................... 32

Removing or changing borders ......................................................................................... 32

Adding shading .................................................................................................................. 33

Fill versus pattern ....................................................................................................... 33

Applying shading ....................................................................................................... 34

Adding horizontal lines ..................................................................................................... 35

Creating Bulleted or Numbered Lists ....................................................................................... 36

Creating bulleted lists ........................................................................................................ 36

Customizing a bulleted list ................................................................................................ 38

Picking another bullet image ...................................................................................... 38

Modifying a bullet’s font ..................................................................................... 39

Selecting a special character ............................................................................... 39

Selecting a bullet picture ..................................................................................... 39

Changing list positions ............................................................................................... 40

Creating numbered lists ..................................................................................................... 40

Customizing numbered lists .............................................................................................. 41

Restarting and continuing numbering ............................................................................... 42

Adding unbulleted or unnumbered paragraphs to a list .................................................... 43

Ending bulleted or numbered lists ..................................................................................... 43

Creating outline numbered lists ......................................................................................... 44

Customizing outline numbered lists .................................................................................. 44

Creating list styles .............................................................................................................. 46

Paragraphs and Pagination ........................................................................................................ 47

Hyphenation .............................................................................................................................. 49

Using automatic hyphenation ............................................................................................ 49

Using manual hyphenation ................................................................................................ 50

Using nonbreaking and optional hyphens ......................................................................... 51

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 51

Chapter 3: Configuring Outlook 2003 ......................................................... 53

Configuring E-mail Accounts ................................................................................................... 53

Using the E-mail Accounts Wizard ................................................................................... 54

Configuring Exchange Server accounts ............................................................................ 55

Setting general properties ........................................................................................... 57

Setting advanced options ............................................................................................ 57

Setting the offline store location ................................................................................ 59

Configuring security settings ..................................................................................... 60

Configuring connection settings ................................................................................. 61

Configuring Remote Mail settings ............................................................................. 62

Configuring POP3 and IMAP accounts ............................................................................ 62

General settings .......................................................................................................... 64

Outgoing server settings ............................................................................................. 65

Connection settings .................................................................................................... 65

Advanced settings ....................................................................................................... 65

POP3 delivery ..................................................................................................... 66

IMAP folders ....................................................................................................... 67

Contents

Understanding where Outlook stores your POP3 and IMAP messages .................... 67

Configuring HTTP accounts .............................................................................................. 67

Adding Data Files ..................................................................................................................... 68

Creating and Managing Outlook Profiles ................................................................................. 71

Creating an Outlook profile ............................................................................................... 71

Copying a profile ............................................................................................................... 73

Switching between profiles ............................................................................................... 73

Configuring Message Delivery Options ................................................................................... 73

Setting Your E-mail Options ..................................................................................................... 74

Setting the e-mail preferences ........................................................................................... 74

Setting the mail format options ......................................................................................... 78

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 79

Chapter 4: Essential Excel Worksheet Operations .................................... 81

Learning the Fundamentals of Excel Worksheets .................................................................... 81

Working with Excel’s windows ......................................................................................... 81

Moving and resizing windows ................................................................................... 83

Switching among windows ........................................................................................ 83

Closing windows ........................................................................................................ 84

Making a worksheet the active sheet ................................................................................. 84

Adding a new worksheet to your workbook ..................................................................... 85

Deleting a worksheet you no longer need ......................................................................... 86

Changing the name of a worksheet ................................................................................... 86

Changing a sheet tab’s color .............................................................................................. 87

Rearranging your worksheets ............................................................................................ 87

Hiding and unhiding a worksheet ...................................................................................... 89

Controlling the Worksheet View .............................................................................................. 90

Viewing a worksheet in multiple windows ....................................................................... 90

Comparing sheets side by side .......................................................................................... 91

Splitting the worksheet window into panes ....................................................................... 92

Keeping the titles in view by freezing panes ..................................................................... 93

Zooming in or out for a better view .................................................................................. 94

Saving your view settings .................................................................................................. 95

Monitoring cells with a Watch Window ............................................................................ 96

Working with Rows and Columns ............................................................................................ 96

Inserting rows and columns ............................................................................................... 96

Deleting rows and columns ............................................................................................... 97

Hiding rows and columns .................................................................................................. 98

Changing column widths and row heights ........................................................................ 98

Changing column widths ............................................................................................ 99

Changing row heights ................................................................................................. 99

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 100

xi

xii

Contents

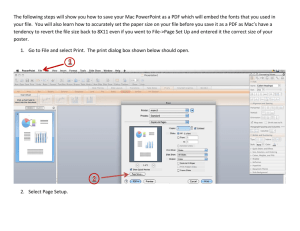

Chapter 5: Developing Your PowerPoint Action Plan .............................. 101

Step 1: Identifying Your Audience and Purpose .................................................................... 101

Step 2: Choosing Your Presentation Method ......................................................................... 104

Speaker-led presentations ................................................................................................ 105

Self-running presentations ............................................................................................... 106

User-interactive presentations ......................................................................................... 107

Step 3: Choosing Your Delivery Method ............................................................................... 108

Step 4: Choosing the Appropriate Template and Design ....................................................... 109

Step 5: Developing the Content .............................................................................................. 110

Step 6: Creating the Visual Image .......................................................................................... 110

Step 7: Adding Multimedia Effects ........................................................................................ 111

Step 8: Creating the Handouts and Notes ............................................................................... 112

Step 9: Rehearsing the Presentation ....................................................................................... 113

Rehearsing a live presentation ......................................................................................... 113

Rehearsing a self-running presentation ........................................................................... 113

Rehearsing a user-interactive presentation ...................................................................... 114

Step 10: Giving the Presentation ............................................................................................ 115

Step 11: Assessing Your Success and Refining Your Work ................................................... 115

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 116

Chapter 6: Introducing Publisher .............................................................. 119

The Publisher Workspace ....................................................................................................... 119

Using Publication Designs ...................................................................................................... 121

Working with Text .................................................................................................................. 123

Typing in text ................................................................................................................... 123

Inserting a text file ........................................................................................................... 124

Autoflow and linked frames ............................................................................................ 125

Formatting text ................................................................................................................. 126

Formatting toolbar buttons ....................................................................................... 126

Format menu options ................................................................................................ 127

The Measurements toolbar .............................................................................................. 129

Working with Graphics ........................................................................................................... 130

Inserting a picture file ...................................................................................................... 130

Inserting a Clip Organizer image ..................................................................................... 130

Inserting a scanner or camera image ............................................................................... 131

Formatting pictures .......................................................................................................... 131

Drawing lines and shapes ................................................................................................ 134

Working with Tables ............................................................................................................... 134

Inserting a table ................................................................................................................ 134

Entering data into a table ................................................................................................. 135

Editing a table .................................................................................................................. 135

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 136

Chapter 7: Building FrontPage Web Sites ................................................ 137

Web Design Strategies ............................................................................................................ 137

Why start with site design? .............................................................................................. 137

Contents

Defining navigational links ............................................................................................. 138

Defining Link Bars in Shared Borders ................................................................................... 141

Customizing links ............................................................................................................ 143

Adding links to page content .................................................................................... 143

Adding links to a shared border ............................................................................... 144

Adding link bars to page content .............................................................................. 144

Changing navigation labels ...................................................................................... 144

Importing an Existing Web Site .............................................................................................. 145

Importing files into a Web ............................................................................................... 145

Importing a Web site into a FrontPage Web .................................................................... 146

Using Web Templates and Wizards ........................................................................................ 148

One Page Web .................................................................................................................. 148

Using the Corporate Presence Web Wizard .................................................................... 148

Customer Support Web .................................................................................................... 149

Using the Database Interface Web Wizard ...................................................................... 150

Discussion Web Wizard ................................................................................................... 150

Empty Web ...................................................................................................................... 151

Import Web Wizard .......................................................................................................... 151

Personal Web ................................................................................................................... 151

Project Web ...................................................................................................................... 151

SharePoint Team Web ...................................................................................................... 152

Generating a Web site using the Corporate Presence Web Wizard .......................... 152

Creating Basic Web Page Content .......................................................................................... 153

Editing Web page text ...................................................................................................... 154

Inserting breaks ................................................................................................................ 154

Adding horizontal lines ................................................................................................... 155

Placing comments ............................................................................................................ 155

Inserting symbols ............................................................................................................. 156

Using Page Templates ............................................................................................................. 157

Other Views ............................................................................................................................ 158

Folders view ..................................................................................................................... 159

Reports view .................................................................................................................... 160

Hyperlinks view ............................................................................................................... 161

Tasks view ........................................................................................................................ 162

Global Site Editing .................................................................................................................. 163

Spell checking your entire site ........................................................................................ 163

Replacing text throughout a site ...................................................................................... 164

Editing Web page content ................................................................................................ 164

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 165

Chapter 8: Understanding and Creating Access Reports ....................... 167

Understanding Reports ........................................................................................................... 167

What types of reports can you create? ............................................................................. 168

Tabular reports .......................................................................................................... 168

Columnar reports ...................................................................................................... 169

Mailing labels ........................................................................................................... 170

xiii

xiv

Contents

The difference between reports and forms ...................................................................... 171

The process of creating a report ...................................................................................... 172

Defining the report layout ........................................................................................ 172

Assembling the data ................................................................................................. 173

Creating a Report with Report Wizards .................................................................................. 173

Creating a new report ...................................................................................................... 173

Choosing the data source ................................................................................................. 174

Choosing the fields .......................................................................................................... 174

Selecting the grouping levels ........................................................................................... 175

Defining the group data ................................................................................................... 176

Selecting the sort order .................................................................................................... 177

Selecting summary options .............................................................................................. 177

Selecting the layout ......................................................................................................... 178

Choosing the style ........................................................................................................... 179

Opening the report design ............................................................................................... 180

Using the Print Preview window ..................................................................................... 180

Viewing the Report Design window ............................................................................... 182

Printing a Report ..................................................................................................................... 182

Saving the Report .................................................................................................................... 183

Starting with a Blank Form ..................................................................................................... 183

The Design Window toolbar ............................................................................................ 184

Banded Report Writer Concepts ............................................................................................. 185

How sections process data ............................................................................................... 186

The Report Writer sections .............................................................................................. 188

Report header section ............................................................................................... 189

Page header section .................................................................................................. 189

Group header ............................................................................................................ 190

Detail section ............................................................................................................ 190

Group footer ............................................................................................................. 190

Page footer ................................................................................................................ 190

Report footer ............................................................................................................. 191

Creating a New Report ........................................................................................................... 191

Creating a new report and binding it to a query .............................................................. 193

Defining the report page size and layout ......................................................................... 194

Placing fields on the report .............................................................................................. 195

Displaying the field list ............................................................................................ 196

Selecting the fields for your report ........................................................................... 197

Dragging fields onto your report .............................................................................. 197

Resizing a section ............................................................................................................ 198

Working with unattached label controls and text ............................................................ 198

Creating unattached labels ........................................................................................ 199

Modifying the appearance of text in a control ......................................................... 199

Working with text boxes and their attached label controls ............................................. 200

Creating and using text box controls ........................................................................ 200

Entering an expression in a text control ................................................................... 201

Sizing a text box control or label control ................................................................. 202

Contents

Changing the size of a label control ......................................................................... 202

Deleting and Cutting attached labels from text controls .......................................... 204

Pasting labels into a report section ........................................................................... 204

Moving label and text controls ................................................................................. 205

Modifying the appearance of multiple controls ....................................................... 206

Changing label and text box control properties .............................................................. 207

Growing and shrinking text box controls ........................................................................ 208

Sorting and grouping data ............................................................................................... 209

Creating a group header or footer ............................................................................ 211

Changing the group order ......................................................................................... 213

Removing a group header or footer ......................................................................... 213

Hiding a section ........................................................................................................ 213

Sizing a section ......................................................................................................... 214

Moving controls between sections ........................................................................... 214

Adding page breaks ......................................................................................................... 215

Making the Report Presentation Quality ................................................................................ 216

Adjusting the Page Header .............................................................................................. 218

Creating an expression in the Group Header .................................................................. 219

Changing the picture properties and the Detail section .................................................. 220

Creating a standard page footer ....................................................................................... 221

Saving your report ........................................................................................................... 222

Part II: Collaborating and Integrating

with Microsoft Office 2003 ................................................. 225

Chapter 9: Building Integrated Documents ............................................. 227

Inserting Objects from Other Applications ............................................................................ 228

Copy and paste ................................................................................................................. 228

Using Paste Special in Word .................................................................................... 228

Choosing a paste method .......................................................................................... 229

Using the Insert Object command ................................................................................... 229

Working with Embedded Objects ........................................................................................... 230

Working with Linked Objects ................................................................................................. 232

Moving and resizing linked objects ................................................................................. 233

Editing and updating links ............................................................................................... 233

Using the Locked and Save picture options .................................................................... 234

Other Methods of Sharing Data .............................................................................................. 234

Sending a Word document to PowerPoint ....................................................................... 234

Analyzing Access data in Excel ...................................................................................... 236

Publishing Access reports with Word .............................................................................. 236

Merging Access data in Word .......................................................................................... 236

Sending a PowerPoint presentation to Word ................................................................... 237

Sharing Data with XML ......................................................................................................... 238

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 238

xv

xvi

Contents

Chapter 10: Integrating Outlook with Other Applications ...................... 241

Integrating Outlook with Office ............................................................................................. 241

Creating a Mail Merge ............................................................................................................ 244

Getting names from contacts ........................................................................................... 244

Sending an E-mail from an Application ................................................................................. 249

Importing and Exporting Data ................................................................................................ 252

Importing information into Outlook ................................................................................ 253

Exporting information from Outlook .............................................................................. 254

Saving Outlook messages ................................................................................................ 254

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 255

Chapter 11: Comments and Reviewing Functions in Word ..................... 257

Placing Comments in Documents ........................................................................................... 258

Working with comments .................................................................................................. 259

Inserting voice comments ................................................................................................ 260

Changing and manipulating comments ........................................................................... 262

Reviewing comments ............................................................................................... 263

Printing comments .................................................................................................... 265

Highlighting text .............................................................................................................. 265

Using Reviewing Tools ........................................................................................................... 266

Adding revision marks ..................................................................................................... 266

Viewing changes .............................................................................................................. 267

Reviewing, accepting, and rejecting changes .................................................................. 268

Customizing revision marks ............................................................................................ 269

Comparing and merging documents ................................................................................ 270

Comparing documents .............................................................................................. 271

Merging comments and revisions from multiple reviewers ..................................... 272

Comparing side by side ................................................................................................... 273

Reading Layout View ............................................................................................................. 273

Moving around in Reading Layout view ......................................................................... 275

Changing text size ........................................................................................................... 276

Editing in Reading Layout view ...................................................................................... 276

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 277

Chapter 12: Sharing Excel Data with Other Applications ....................... 279

Understanding Data Sharing ................................................................................................... 279

Pasting and Linking Data ........................................................................................................ 280

Using the Clipboards ....................................................................................................... 280

Linking data ..................................................................................................................... 282

Copying Excel data to Word ............................................................................................ 283

Pasting without a link ............................................................................................... 284

Pasting with a link .................................................................................................... 284

Embedding Objects in Documents ......................................................................................... 284

Embedding an Excel range in a Word document ............................................................ 285

Creating a new Excel object in Word .............................................................................. 287

Embedding objects in an Excel worksheet ...................................................................... 288

Contents

Working with XML Data ........................................................................................................ 289

What is XML? ................................................................................................................. 289

Importing XML data by using a map .............................................................................. 290

Importing XML data to a list ........................................................................................... 292

Exporting XML data from Excel ..................................................................................... 293

Chapter 13: Team Collaboration on a Draft PowerPoint Presentation ... 295

Sharing Your Presentation File on a LAN .............................................................................. 295

Sharing the presentation locally ...................................................................................... 296

Sharing in Windows 2000 or XP .............................................................................. 296

Posting a presentation to an Exchange folder ................................................................. 298

Mailing a presentation via e-mail ........................................................................................... 299

Sharing a Presentation in a Document Workspace ................................................................. 300

Working with Comments ........................................................................................................ 303

Adding a comment ........................................................................................................... 303

Moving, editing, and deleting comments ........................................................................ 304

Reviewing comments ...................................................................................................... 304

Incorporating Changes from Reviewers ................................................................................. 305

Merging review revisions ................................................................................................ 305

Accepting or rejecting revisions ...................................................................................... 306

Using the Reviewing toolbar for revisions ...................................................................... 306

Finishing a review of revisions ........................................................................................ 307

Live Collaboration with NetMeeting ...................................................................................... 307

Live Collaboration with Windows Messenger ....................................................................... 308

Running Windows Messenger ......................................................................................... 308

Inviting someone to share PowerPoint ............................................................................ 309

Giving another participant control ................................................................................... 312

Taking control as a participant ......................................................................................... 314

Chatting with other participants ...................................................................................... 314

Using the Whiteboard ...................................................................................................... 315

Ending an application sharing session ............................................................................. 316

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 316

Chapter 14: Integrating FrontPage with Office Applications ................. 317

From Office to FrontPage ....................................................................................................... 318

Moving from Word to FrontPage .................................................................................... 318

Attaching text files to a Web site .............................................................................. 319

How Word creates HTML files ................................................................................ 320

Copying and pasting text into Web pages ................................................................ 320

Creating Web sites from Publisher files .......................................................................... 321

Sending Excel objects to FrontPage ................................................................................ 322

Copying tables into FrontPage ................................................................................. 322

Exporting Excel sheets as HTML pages .................................................................. 323

Sending charts to FrontPage ..................................................................................... 324

Saving Excel workbooks as folders ......................................................................... 324

From PowerPoint to FrontPage ....................................................................................... 326

xvii

xviii

Contents

Converting slides to Web pages ............................................................................... 326

Integrating a slideshow into FrontPage .................................................................... 327

Importing files into Webs ................................................................................................ 328

Importing Word and Excel files into a Web site ...................................................... 328

Adding Office Web Components to Web Pages ..................................................................... 330

Adding Office spreadsheets ............................................................................................. 330

Defining ActiveX control properties for a spreadsheet ........................................... 332

Defining spreadsheet properties ............................................................................... 334

Adding Office charts ........................................................................................................ 335

Changing chart properties ........................................................................................ 336

Controlling charts using the chart menu .................................................................. 337

Presenting a database table in a Web spreadsheet ........................................................... 339

Creating Office PivotTables ............................................................................................ 341

Connecting a PivotTable to an Excel data source .................................................... 342

Adding fields to a PivotTable ................................................................................... 345

Formatting and calculating PivotTable data ............................................................. 347

Implementing an Office spreadsheet Web component ............................................. 348

From FrontPage to Office 2003 .............................................................................................. 349

Sending data to Word mail-merge files ........................................................................... 350

Sending data to Excel ...................................................................................................... 351

Sending reports to Excel .................................................................................................. 351

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 352

Chapter 15: Exchanging Access Data with Office Applications ............. 353

Using Automation to Integrate with Office ............................................................................ 354

Creating Automation references ...................................................................................... 354

Early binding an object ............................................................................................. 354

Late binding an object .............................................................................................. 356

Creating an instance of an Automation object ................................................................ 358

Using the New keyword to create a new instance ................................................... 358

Using the CreateObject function to create a new instance ....................................... 358

Getting an existing object instance .................................................................................. 359

Working with Automation objects ................................................................................... 360

Closing an instance of an Automation object .................................................................. 361

An Automation Example Using Word .................................................................................... 361

Creating an instance of a Word object ............................................................................. 365

Making the instance of Word visible ............................................................................... 366

Creating a new document based on an existing template ............................................... 366

Using Bookmarks to insert data ...................................................................................... 367

Activating the instance of Word ...................................................................................... 367

Moving the cursor in Word .............................................................................................. 367

Closing the instance of the Word object .......................................................................... 367

Inserting pictures by using Bookmarks ........................................................................... 368

Using Office’s Macro Recorder ....................................................................................... 368

Contents

Chapter 16: Collaborating on a Network .................................................. 373

Resource Sharing and Security ............................................................................................... 373

Setting file-sharing options when saving ........................................................................ 373

Protecting documents ...................................................................................................... 375

Protecting documents in Word ................................................................................. 375

Protecting documents in Excel ................................................................................. 377

Protecting files in Access and PowerPoint ............................................................... 378

Using Information Rights Management tools ................................................................. 379

Sharing Excel Workbooks ...................................................................................................... 381

Creating a shared workbook ............................................................................................ 381

Reviewing changes .......................................................................................................... 383

Collaborating in PowerPoint ................................................................................................... 384

Sharing Access Databases ...................................................................................................... 386

Using passwords .............................................................................................................. 386

Creating user and group accounts .................................................................................... 387

Securing the database ...................................................................................................... 388

Assigning permissions ..................................................................................................... 388

Encryption ........................................................................................................................ 389

Distributing Office Documents ............................................................................................... 389

Sharing documents via e-mail ......................................................................................... 390

Sending a document (without routing it) ................................................................. 390

Routing a document .................................................................................................. 390

Sending documents that aren’t already open ............................................................ 392

Posting documents to Exchange folders .................................................................. 392

Sending documents to online meeting participants .................................................. 392

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 392

Chapter 17: Windows SharePoint Services with Office System ............. 393

Working with SharePoint Sites and SharePoint Lists ............................................................. 394

Accessing SharePoint Services sites ............................................................................... 394

Windows SharePoint Services site permissions .............................................................. 397

Exploring the Windows SharePoint Services site ........................................................... 398

Adding items to existing lists .......................................................................................... 399

Creating new Windows SharePoint Services lists and libraries ...................................... 401

Working with Datasheet views and linking lists to Excel and Access ............................ 401

Collaborative Document Authoring ....................................................................................... 407

Exploring Document Libraries and Shared Workspaces ................................................. 408

Creating Shared Workspaces ........................................................................................... 412

Working with Shared Workspaces inside Office 2003 applications ............................... 413

SharePoint as a Central Contacts and Calendar Server .......................................................... 421

Making SharePoint contacts available to Outlook .......................................................... 423

Conducting an Online Meeting with the Meeting Workspace ............................................... 424

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 426

xix

xx

Contents

Part III: Beyond Mastery: Initiative within Office ................. 429

Chapter 18: Getting Organized with Outlines and Master Documents .. 431

Using Outlines ........................................................................................................................ 431

Understanding Outline View ........................................................................................... 432

Creating outlines .............................................................................................................. 433

Rearranging your outline ................................................................................................. 436

Selecting in Outline view ......................................................................................... 436

Promoting and demoting outline levels .................................................................... 437

Moving outline headings .......................................................................................... 438

Using keyboard shortcuts .................................................................................. 438

Viewing both Outline and Normal view at once ............................................... 439

Printing an outline ........................................................................................................... 440

Copying an outline ........................................................................................................... 441

Understanding Master Documents ......................................................................................... 441

The Master Document view ............................................................................................ 442

Building a master document ............................................................................................ 444

Starting from scratch ................................................................................................ 444

Converting an existing document ............................................................................. 446

Inserting existing documents into a master document ............................................. 446

Working with master documents ..................................................................................... 446

Working with subdocuments ........................................................................................... 447

Opening a subdocument ........................................................................................... 447

Renaming or moving a subdocument ....................................................................... 448

Removing subdocuments ......................................................................................... 448

Rearranging the order of subdocuments .................................................................. 449

Splitting subdocuments ............................................................................................ 449

Merging subdocuments ............................................................................................ 449

Sharing subdocuments .............................................................................................. 449

Summary ................................................................................................................................. 450

Chapter 19: Processing Outlook Messages Automatically ..................... 451

Securing Against HTML Content ........................................................................................... 451

Blocking external HTML content ................................................................................... 452

Configuring security zones .............................................................................................. 453

Using Rules ............................................................................................................................. 454

Using the Rules Wizard ................................................................................................... 454

Creating a rule .......................................................................................................... 454

Controlling rule processing order ............................................................................. 459

Running rules manually ............................................................................................ 460

Modifying and copying rules ................................................................................... 461

Responding automatically to messages ........................................................................... 461

Importing, exporting, and backing up rules .................................................................... 462

Back up rules to a file ............................................................................................... 463

Import rules from a file ............................................................................................ 463

Contents

Filtering junk and adult content mail .............................................................................. 464