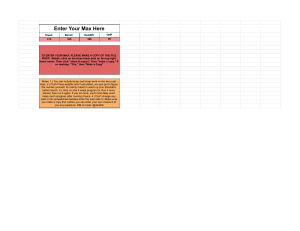

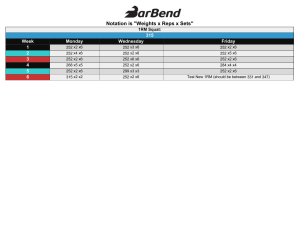

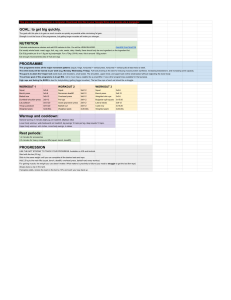

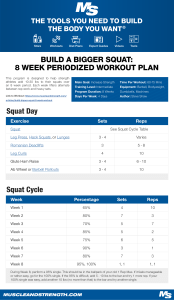

THINK STRONG THINK STRONG A SMART, SIMPLE WAY TO STRENGTH Let go of the thoughts that don’t make you strong. Think Strong 2 Week 1 Day 1 OFFSEASON Day 2 Day 3 Exercise Work Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 4 5 74 Bench Press 4 5 74 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Deadlift 4 5 74 Overhead Press 4 5 74 Chin/Pull-Up 3 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Squat 5 5 59 Bench Press 5 5 59 Barbell Row 3 10 — Squat 6 2 85 Bench Press 6 2 85 Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Deadlift 6 2 85 Overhead Press 6 2 85 Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Squat 5 2 68 Bench Press 5 2 68 Barbell Row 4 10 — Squat 4 3 85 Bench Press 4 3 85 Reverse Hyper 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — Deadlift 4 3 85 Overhead Press 4 3 85 Chin/Pull-Up 5 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 5 10 — Squat 5 3 68 Bench Press 5 3 68 Barbell Row 5 10 — Week 2 Day 1 Block 1 Day 2 Day 3 Week 3 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Week 4 Day 1 OFFSEASON Day 2 Day 3 Exercise Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 3 5 77 Bench Press 3 5 77 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Deadlift 3 5 77 Overhead Press 3 5 77 Chin/Pull-Up 3 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Squat 5 5 61 Bench Press 5 5 61 Barbell Row 3 10 — Squat 5 2 87 Bench Press 5 2 87 Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Deadlift 5 2 87 Overhead Press 5 2 87 Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Squat 5 2 69 Bench Press 5 2 69 Barbell Row 4 10 — Squat 3 3 87 Bench Press 3 3 87 Reverse Hyper 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — Deadlift 3 3 87 Overhead Press 3 3 87 Chin/Pull-Up 5 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 5 10 — Squat 5 3 69 Bench Press 5 3 69 Barbell Row 5 10 — Week 5 Day 1 Block 2 Day 2 Day 3 Week 6 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Week 7 Day 1 OFFSEASON Day 2 Day 3 Exercise Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 2 5 80 Bench Press 2 5 80 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Deadlift 2 5 80 Overhead Press 2 5 80 Chin/Pull-Up 3 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Squat 5 5 64 Bench Press 5 5 64 Barbell Row 3 10 — Squat 3 2 90 Bench Press 3 2 90 Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Deadlift 3 2 90 Overhead Press 3 2 90 Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Squat 5 2 72 Bench Press 5 2 72 Barbell Row 4 10 — Squat 2 3 90 Bench Press 2 3 90 Reverse Hyper 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — Deadlift 2 3 90 Overhead Press 2 3 90 Chin/Pull-Up 5 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 5 10 — Squat 5 3 72 Bench Press 5 3 72 Barbell Row 5 10 — Week 8 Day 1 Block 3 Day 2 Day 3 Week 9 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Week 1 MEET PREP Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Exercise Work Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 2 3 91/88 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Deadlift 2 3 91/88 Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Bench Press 2 3 91/88 Chin/Pull-Up 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Squat 2 2 96/92 Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Deadlift 2 2 96/92 Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Bench Press 2 2 96/92 Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Squat 4 1 101/97/94/94 Reverse Hyper 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — Deadlift 4 1 101/97/94/94 Glute-Ham Raise 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — Bench Press 4 1 101/97/94/94 Chin/Pull-Up 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — Week 2 Day 1 Block 1 Day 2 Day 3 Week 3 Day 1 Day 2 You’ll deload before and after this training cycle, so plan for 8 total weeks of meet prep. See Chapter 4 for details. Day 3 Week 4 MEET PREP Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Exercise Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 2 3 88/85 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Deadlift 2 3 88/85 Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Bench Press 2 3 88/85 Chin/Pull-Up 5 5 — Abs 3 10 — Squat 1 3 93 Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Deadlift 1 3 93 Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Bench Press 1 3 93 Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Squat 1 2 98 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Deadlift 1 2 98 Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Bench Press 1 2 98 Chin/Pull-Up 5 5 — Abs 3 10 — Week 5 Day 1 Block 2 Day 2 Day 3 Week 6 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 INTRODUCTION BOOK CONTENTS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. INTRODUCTION THE OFFSEASON PROGRAM CUSTOMIZING THE OFFSEASON PROGRAM THE MEET PREP PROGRAM APPENDIX: FAQS & TECHNIQUE This book is the culmination of fifteen years in strength training and competitive powerlifting. When I started lifting, I felt lost: none of my friends trained; my parents were against it; and to my wrestling and cross-country coaches, lifting was an afterthought. Today, I know that their attitudes were the result of a hundred years of fear and misinformation about the nature of strength training and exercise in general, but back then, all I knew was frustration. It wasn’t until several years later that I began to understand how to train properly, and even then, I had to teach myself, mostly by reading articles from EliteFTS and following whatever cookie-cutter program I could find that looked hard. That’s all I cared about: training heavy and hard. I believed that as long as I pushed myself to the limit, day in and day out, I’d reach my goals. That was a terrible attitude to have, of course — I was constantly beat up and run down, and even though I was shredded to the bone, I had little size or strength. I Think Strong 8 couldn’t accept that I needed to take rest days, needed to give myself more time to recover. The four-day-per-week programs appeared in my mind as excuses to slack off; the idea to train with light weights seemed unthinkable. It took me almost a decade to realize how misguided my attitude was, and only then did I begin to make real progress. In fact, in two years’ time, I added one hundred pounds to my bench press, two hundred to my deadlift, and nearly two hundred and fifty to my squat. The difference was that over those two years, I learned how to Think Strong. First, I found what worked for me: multiple sets with nearbut-not-quite-max loads, an almost exclusive focus on the squat, bench press, and deadlift, a search for constant improvement in technique, and ample time for recovery. Those four things form the basis of the Think Strong Method. Almost. There’s one last part that’s more important than anything else, something that I realized only after I’d achieved everything I set out to do when I started lifting (and even a bit more). It’s the idea that everyone is different, and you have to find what works for you — not what works for someone else. I spent so many years searching for the guru with all the right answers, the person who could just tell me what to do so that I’d not have to struggle with the overwhelming amount of conflicting information and opinions that littered the Internet. There is no guru with all the answers. I struggled for so long because my body is a bit odd; I have a short torso and long legs, but not femurs. My arms are too long for my body and my torso too thick. So I don’t fit any of the “textbook” ideas of exercise technique. My squat looks painfully awkward, my deadlift stance changes from day to day and week to week, and my bench press has never felt quite right. But it all works for me. You’ll have to find what works for you, too, and this book is designed to help you on that journey by taking you progressively through the steps of Thinking Strong. You’ll begin with the basic method, a simple, straightforward program with little variation or flexibility. Over time, you’ll develop your own customized program, one that incorporates exercises that train your weakpoints, highlight your strengths, account for your recovery ability — everything tailored to you, not to someone else or some intangible ideal. It’s not easy. It takes hard work, patience, dedication, and a positive mental attitude. But trust that if you put in the time and effort, results will come. If you only take that one idea away from this book, you’ll come out on top. Think Strong 9 THIS BOOK IS DIFFERENT. anger, disappointment, and moving on to a new, more reasonable program. When it comes to programming, I’ve tried almost everything. I started training in 2001, and I spent the first decade or so of my lifting career in search of that perfect program — the one that would make me big, strong, lean, and athletic. I never found it. Instead, I wasted years of training on cookie-cutter programs that either simply weren’t appropriate to my level of experience, or just weren’t a good program for anyone. The Think Strong method is different. It’s built on the time-tested principles of periodization, but at the same time, it’s designed in a way to smooth the transition between phases so that you never have to attempt a weight you’re not prepared to lift. It also explains how those weights are chosen, so that if you ever do struggle with a workout, you’re informed enough to adjust the program to fit your body more appropriately. After I began my doctoral degree at the University of Texas at Austin, studying the history of strength and fitness, I started to understand what all those programs were missing. Almost none of the bodybuilding programs in muscle magazines applied the principles of periodization effectively. In fact, most weren’t periodized at all! Some suggested adding two or five or even ten pounds a week to the bar, and promised that if I worked hard enough, I could handle the extra load. Well, I worked my ass off, but about a month or two in I’d hit a plateau and no matter how much I pushed, I just couldn’t squeeze out enough reps with enough weight. The offseason program looks simple, but it’s actually built from a very complex set of pieces that all need to work together to work well. For that reason, it’s very important that you follow the program exactly as written. Changing the sets, reps, or exercises will undermine your progress. Of course, rules were meant to be broken, and later in this book you’ll learn how you can modify your training to better fit your needs — but not until you have some solid experience with the base program. Other programs, usually powerlifting-specific ones, did use periodization. But they were full of percentages (and sometimes short on explanation), and usually involved a lot of pretty boring workouts with a pretty light weight. After a few weeks or months, the prescribed weights shot up — above what I was capable of doing. Cue frustration, When, inevitably, you decide that you want to test your limits — either in the gym or the meet — you’ll want to follow the meet prep program for the six weeks leading up to your max attempt. The meet prep program is deceptively simple, because it involves relatively few exercises, but it will demand everything you’ve got, physically and mentally. The meet prep program will set you up for the best possible performance, maximizing all the work you did during the offseason. Think Strong 10 I hope this book can help any lifter who’s struggling with programming, but it’s really intended at the intermediatelevel guy or girl struggling to break through to that next level. Dave Tate calls this the “Dead Zone,” and that’s a perfect description of what this level feels like. If you feel like you’re stuck in the Dead Zone, know that progress is going to be slow, and frustrating. Embrace that, and embrace the process of finding what works for you. Spend the time going through the standard offseason program described in Chapter 2, even if it seems too simple or too easy. Then really dedicate yourself to the process of adjusting your training, as described in Chapter 3. Eventually, you’ll figure out what works, and what doesn’t, and that’s when the gains will come back — never before. Once you’ve gotten to that point, give Chapter 4 a try. Pick out a meet, train for it conservatively, and see if you can’t surpass your own expectations. Eventually, of course, you’ll have to adjust your meet prep strategy, too, but that’s a topic for another book. Good luck. Don’t get discouraged. And Think Strong. Once you’ve finished reading, if you still want a more customized training plan, email me! ben@phdeadlift.com Think Strong 11 BIG FIVE THE FIVE PRINCIPLES #1. STRENGTH IS BUILT BY THE SQUAT, BENCH PRESS, AND DEADLIFT. Yes, there are plenty of other valuable exercises, and many of them are used in this program, too. But the three powerlifts are the most representative measure of overall strength, and will generally do more for your physique than other exercises, too. If those three lifts are improving, you can be confident that your training is going well. #2. STRENGTH IS BUILT WITH MULTIPLE SETS OF LOW REPS. We’ll get into the workings of periodization a little later on, but for now, it’s enough to know that if you want to get stronger, the majority of your training should fall into the 2- to 6-rep range, for 10-24 total repetitions per lift over the course of a given workout. Think Strong 12 #3. STRENGTH IS BUILT FROM EFFORT AND DISCIPLINE. Hard work and consistency are the two most important factors in your success. If you don’t work hard, day in and day out, nothing else you do matters. It’s not supposed to be easy. #5. EVERYONE IS DIFFERENT. Lifting weights is as much an art as a science, and there’s no one technique, program, or diet that works best for everyone. Part of progress is learning what works for you, and so a big part of your education as a lifter is recording your workouts in a way that allows you to identify patterns and optimize your training to best fit your body and your preferences. #4. STRENGTH REQUIRES GOOD TECHNIQUE. If your technique fails to incorporate all of the muscles involved in a given lift, you won’t be able to lift as much as you could with better technique. Even worse, you might develop imbalances that can lead to injuries, and if you’re injured, you can’t train productively or get stronger. But notice this principle says “good technique,” not “perfect technique.” If you’re constantly obsessing about your form, even though you’re performing the lifts safely, then you won’t be able to put in the necessary effort to get stronger. Don’t let “perfect” become the enemy of greatness. Think Strong 13 THE OFFSEASON PROGRAM The offseason program is fairly simple, but it’s worth understanding how it’s designed before you get started. The more you understand about your training, the more you’ll learn about your body. THINKING STRONG IN THE OFFSEASON CHAPTER CONTENTS 1. THE BASICS 2. COMPOUND MOVEMENTS 3. ASSISTANCE MOVEMENTS 4. HEAVY DAYS AND LIGHT DAYS 5. THE WAVED REP SCHEME 6. INCREASING WEIGHT, DECREASING SETS I know it’s easy to just take a quick glance at the program, plug your numbers into the spreadsheet, and get started. And honestly, you won’t go far wrong that way. But it’s better to read the explanations first, so that you can understand why your body responds the way it does. This chapter explains all of that. Again, make sure to follow the program as written. There’s plenty of time to customize your training, and, in fact, the next chapter explains how to do exactly that. But before you do that, you need to learn how the program works and how your body responds to it. 7. FINDING YOUR 1-REP MAX 8. WARMUPS AND RAMP-UPS 9. DELOADING 10.TRACKING YOUR TRAINING 11.TRAINING STYLE Think Strong 15 1. THE BASICS It’s pretty simple: you’ll train using a three-day split (at first — we’ll go over adding a fourth day later on). Every workout follows a full-body template. Days 1 and 2 are heavy, and Day 3 is light. On every training day, you’ll also perform some sort of accessory work for certain muscles. Don’t add any other lifting! If you’re really dying to work out, on your off days, you can do some sort of conditioning (it’s optional, but if you do want to implement conditioning, check out the next Chapter after you’ve completed one training cycle of the standard program). DAY 1 DAY 2 Squat & Bench Press: Medium sets of 5 Deadlift & Overhead Press: Medium sets of 5 Reverse Hyperextension & Abs: 3 sets of 10 Chin or Pull-up & Glute-Ham Raise: 3 sets of 10 Squat & Bench Press: Medium sets of 2 Deadlift & Overhead Press: Medium sets of 2 Reverse Hyperextension & Abs: 4 sets of 10 Chin or Pull-up & Glute-Ham Raise: 4 sets of 10 Squat & Bench Press: Heavy sets of 3 Deadlift & Overhead Press: Heavy sets of 3 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 DAY 3 Squat, Bench Press & Barbell Row: Light sets of 5 Squat, Bench Press & Barbell Row: Light sets of 5 Deload Reverse Hyperextension & Abs: 5 sets of 10 Chin or Pull-up & Glute-Ham Raise: 5 sets of 10 The Offseason Program 16 THE TRAINING SPLIT Your training is planned in three-week blocks. Each week uses multiple sets of either 2, 3, or 5 repetitions on the heavy, main movements. So, for example, on week 1, you’ll do sets of 5 for the squat and bench on day 1, and the deadlift and overhead press on day 2. On week 2, you’ll do sets of 2 for everything, and so on. ➡ Day 1: Squat and Bench Press emphasis ➡ Day 2: Deadlift and Overhead Press emphasis ➡ Day 3: Light work for the Squat, Bench Press, and Barbell Row THE TRAINING BLOCK Three weeks equals one training block. Each training block, you increase the weight and decrease the number of sets. After three blocks, you test your new one-rep max. So, to summarize: three workouts per week, three weeks per block, three blocks per training cycle. ➡ Week 1: Sets of 5 with a weight you should be comfortable using for 6-7 reps ➡ Week 2: Sets of 2 with a weight you should be comfortable using for 3-4 reps ➡ Week 3: Sets of 3 with the same weight as week 2 Easy, right? And that’s pretty much all you need to know to dive right in. We’ll look at some of the aspects of the program in more detail, though, so you get a better idea of the big picture. BLOCK 1 Week 1 4x5, 74% 1RM Week 2 6x2, 85% 1RM Week 3 4x3, 85% 1RM BLOCK 2 Week 4 3x5, 77% 1RM Week 5 5x2, 87% 1RM Week 6 3x3, 87% 1RM BLOCK 3 Week 7 2x5, 80% 1RM Week 8 3x2, 90% 1RM Week 9 2x3, 90% 1RM These numbers only apply to your first two training days each week. On your light day, you’ll always use 70% of your 1RM for 3x5. Don’t worry if it the numbers seem complicated — you can just plug your 1RMs into the included spreadsheet and it will calculate all three blocks for you. The Offseason Program 17 2. COMPOUND MOVEMENTS You probably already know the benefits of training with heavy, compound movements like the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Heavy, compound lifts build more muscle and strength more quickly than any other alternative. That’s all there is to it. If you can perform a 600-pound squat, 500-pound bench press, and 700-pound deadlift, and follow a decent diet, you’ll have a great physique. Of course, there are lots of good compound movements, but you’ll only be using a few of them. Instead of spreading your effort out, you’ll concentrate it on the best bang-for-your-buck muscle builders. Trust me: if you can deadlift 700 pounds, you won’t have any problems doing lat pulldowns with the whole stack. 3. ASSISTANCE MOVEMENTS Again, the template doesn’t rely on many assistance exercises. Besides the overhead press and barbell row, your main assistance exercises are the chin or pull-up, the reverse hyperextension, the glute-ham raise, and some dedicated ab training. The overhead press, barbell row, and chin or pull-up in particular help to balance the development of the upper body — if you only use the bench press, you won’t really get enough work for the back and might develop shoulder problems. The reverse hyperextension, when performed properly, is the single best assistance exercise you can do for the squat and deadlift. Do not add assistance exercises! They’re just not necessary unless you’re an advanced bodybuilder. Focus on putting all of your effort into the main lifts, and don’t worry about the extras. That said, variety is the spice of life, and you’ll have the opportunity to add some in once you’ve completed a full three-block cycle of the standard program. On your second time through, you can experiment a bit, but make sure you complete a full cycle of the standard program first. The next chapter explains how to customize your training, but only when you’re ready. Finally, you’ll notice there is no weight listed for the assistance exercises. The purpose of these movements is to strengthen the muscle and improve activation, and so the weight itself is secondary. However, you should still train them progressively, and that’s why you’ll be adding a set to your assistance movement every week of each training block. Start week 1 using a light weight, and keep the weight the same throughout the entire training block. Each training block, try to add ten pounds to each assistance movement. So, for example, you might start in week 1 using 20 The Offseason Program 18 pounds on the reverse hyperextension for 3 sets of 10. In week 2, you’ll use 20 pounds for 4x10, and in week 3, 20 pounds for 5x10. In week 4, you’ll go back to 3 sets of 10, but this time using 30 pounds. 4. HEAVY AND LIGHT DAYS I struggled for a long time accepting the value of light training days. If progress means adding weight, why would I ever want to train with less than my best? Eventually, though, I learned that light days have two huge benefits for strength. First, light days give your body a chance to recover from all the hard work of your heavy training days. If you don’t regularly incorporate light days into your program, you probably need to deload once a month or so. I tried that for a while, but I found that the week after a deload, I was always a little sluggish and needed another week to get back in the groove of heavy training. That meant that for every four weeks, I only got two really solid training weeks. By switching to light days instead of deloads, I was able to train more productively for much longer. Note: Deloads are still important, but you don’t need to take them very frequently. Deloads are explained later on in this chapter. Second, light days give you a chance to really practice your technique. Technique is one of the Five Principles, but it takes a long time to perfect, and when using very heavy loads, even the best lifters sometimes suffer from breakdowns in technique. The more you practice with lighter weights, the better you’ll be at maintaining good form when the loads get challenging. On your light days, you’ll use 80% of your heavy day weights — not of your 1RM. That’s challenging enough to make the workout worthwhile, but light enough that you’ll recover from the training very easily. You’ll always do 5 sets on light days, using the same reps as your heavy day. So, for example, if you performed 4 sets of 3 reps with 400 pounds on squat on your heavy day, you’ll do 5 sets of 3 reps with 320 pounds on your light day. 5. WAVED REP SCHEME So, why sets of 5, 2, and 3? Why not 2, 3, and 5, or even (ahem) 5, 3, and 1? Why not sets of 8? I’ve found that any sort of linear rep scheme, where you’re working with progressively higher or lower numbers of reps each week, become very mentally exhausting. It’s a challenge to always add reps or to always add weight, for more than two weeks in a row. The waved approach gives you a mental advantage every time you train. The week of 5 reps is physically challenging, but not mentally, because you know you The Offseason Program 19 could crank out a few more reps if you really needed to. The week of 2 reps is a little harder mentally, because you’re using a much heavier weight than the prior week, but you only need to do it for a double — two quick reps and it’s over. And the week of 3 is very challenging mentally and physically, but you’ve got an advantage, because you used the same load for multiple sets of 2 just one week earlier. You already know you can move the weight! 6. INCREASING WEIGHT, DECREASING SETS Each three-week block of training uses the same number of reps, but fewer sets, and heavier weights, than the prior block, up to a total of three. After three blocks (nine weeks), you can either repeat the whole offsesason program, using a new estimated 1RM for the squat, bench press, and deadlift (based on your week 9 numbers, see “Finding your 1RM” below); or you can move to the meetprep program and train to set a true new 1RM. If you’ve competed in a powerlifting meet recently (within the last six months or so), you already know your 1RMs: just use your best squat, bench press, and deadlift from that meet. That’s the best-case scenario. If you haven’t competed, but have tested your maxes in the gym, those numbers are fine too, as long as you used good form. (It’s a good idea to record your heavy attempts in the gym so that you can analyze them afterward.) If you haven’t tested your 1RM in a meet or in a gym, that’s okay, too. You can use a 1RM calculator to get a pretty good estimate of what you’re capable of. I recommend the Brzycki formula, which is just one of many ways of guessing what your 1RM might be based on higher-rep sets: Weight used for multiple reps ÷ (1.0278 — 0.0278 ✕ number of reps) The fewer reps used in this calculation, the better — a 2RM will be more accurate than a 3RM, which will be more accurate than a 5RM, and so on. Again, you don’t have to do this calculation on your own, since there’s a conversion formula built into the included spreadsheet. 7. FINDING YOUR 1RM Your one-rep max (1RM) is the weight you can lift once with good form. That means squatting below parallel, benching with a full pause on the chest, and deadlifting without straps and without hitching. The Offseason Program 20 8. WARMUPS AND RAMP-UPS Before every workout you should take a general warmup to help prepare your muscles and your mind for training. There’s no one right warmup for everyone, but yours should take at least ten minutes of dedicated work before you ever touch a barbell, and include at least 3-5 minutes of cardiovascular exercise to loosen up. Here’s my preferred warmup: 1. Five minutes of stationary cycling. 2. Self-myofascial release exercises using a foam roller and similar tools, focusing on the tight areas around my hips and shoulders. 3. Dynamic stretching exercises using bands, again focusing on my hips and shoulders. 4. Activation exercises using bands or machines for my glutes and upper back. Most of this warmup is targeted at my specific weaknesses, and it may not be applicable to you. There are tons of great warmup resources on elitefts.com that you can use to design a warmup routine that meets your individual needs. Don’t stress too much about your warmup, though — the most important thing is that you do one. In addition to your general warmup, you should perform a specific warmup for the major exercises of each workout. For the first few warmup sets, the weight and reps don’t matter. For example, you might start out squatting with just the bar for a few reps, and then move up to 135. These early warmup sets help you get more comfortable with the movement pattern. Once you’re within 80% of your target weight for the day, the warmup sets get more important. We’ll call these ramp-up sets, and the ramp-up sets are specifically programmed to ease the transition between warmup and work sets. Your ramp-up sets depend on the number of reps you’re using that week: The Offseason Program 21 STANDARD RAMP-UP PROTOCOL Ramp-Up Set 1: 80% of target weight (TW) for 3 reps Sets of 5 Reps Ramp-Up Set 2: 90% of TW for 2 reps Ramp-Up Set 1: 80% of TW for 2 reps Sets of 2 or 3 Reps Ramp-Up Set 2: 90% of TW for 1 rep ADVANCED RAMP-UP PROTOCOL Ramp-Up Set 1: 75% of TW for 3 reps Sets of 5 Reps Ramp-Up Set 2: 85% of TW for 2 reps Ramp-Up Set 3: 92% of TW for 2 reps Ramp-Up Set 1: 80% of TW for 2 reps Sets of 2 or 3 Reps Ramp-Up Set 2: 87% of TW for1 rep Ramp-Up Set 3: 92-95% of TW for 1 rep The standard ramp-up sets are calculated automatically for you in the included spreadsheet. The Offseason Program 22 9. DELOADING With this program, you shouldn’t feel the need to deload very often. The program is designed to build momentum from week to week and block to block, not to break you down. That said, sometimes life gets in the way, and maybe one week you don’t recover very well because you were sick, stressed, or whatever. That’s no problem! You can take a deload week between any block you wish. Try your best to only take deloads between and not during blocks (so after your week of 3 reps, not after your week of 5s or 2s). If you absolutely can’t avoid deloading during a block, though, that’s not a deal breaker. Just pick up the next wherever you left off. Some signs you might need a deload: • You struggle to complete a workout, even though last week you managed all of your sets and reps easily. • You have trouble sleeping or loss of appetite, but you’re not sick. • • You are sick. • You no longer feel excited about training. Remember Principle #5: everyone is different. If you feel that you need a deload, take one! THE DELOAD WEEK ➡ Day 1: Squat & Bench Press, 5x5 with 65% 1RM ➡ Day 2: Deadlift & Overhead Press, 5x5 with 65% 1RM ➡ Day 3: Assistance Circuit (see below) On day 3, you’ll perform a giant set of Leg Press, Lat Pulldown, and Dumbbell Bench Press. Do one set of 10 reps on each exercise using a weight you could do for 20 reps. Take no rest between sets. After you complete one full giant set (so one set of each exercise, and three total sets), rest five minutes, and then repeat, up to a total of three full giant sets (nine total sets). After you deload, just resume training as normal, picking up wherever you left off. You have life or job events that are causing you significant stress outside of the gym. The Offseason Program 23 10. TRACKING YOUR TRAINING I’ve personally used this method for eighteen months straight before I felt the need to experiment with anything else — and even then, the other methods I tried weren’t as productive as this system. In short, this is a program you can use for years with great success. It’s that long-term, consistent progress that builds elite lifters. But long-term success requires planning, and to plan where you’re headed, you need to keep track of where you’ve been. You must track your training carefully. It’s not enough to just write down the sets, reps, and weight, either. You need to track your bodyweight, your technique, and the effort you put into your training. It’s not as complicated as it sounds. In fact, you can track almost everything in the included spreadsheet, and it’s not much more difficult to write it down in a notebook. Here’s how to do it: 1. Weigh yourself weekly. You should weigh yourself first thing in the morning, without clothes, using the same scale and on the same day of the week. Record that number. 2. Each workout, record the sets, reps, weights, and reps in the tank based on your actual performance. 3. Occasionally you should record video of your workouts to monitor your technique. Adding weight to your lifts won’t build strength if you consistently let your form break down, and video can help keep you honest. There’s more information about technique in the Appendix. If you read that carefully, you might be a little confused by part of #2. Let’s look at reps in the tank a little more closely. REPS IN THE TANK Ever had an awful workout before? The weights feel too heavy, your body feels too sluggish, your mind checked out before you even walked in the gym. We’ve all been there, and it’s never fun. On the other hand, some workouts, everything just seems to click. You’re in the zone, working weights feel like warmups, and you finish your workout feeling fresher than when you started. These types of fluctuations will always happen, no matter how long you train or how much strength you build. Most programs don’t take that into account! If you have a bad day, you’re pretty much SOL. Tracking your reps in the tank helps you deal with bad workouts, so that you have more good ones. Every week, the loads are planned so that even if you’re having a rough day, you can still complete a given workout (although you might have to take very long rests between sets). The Offseason Program 24 On good days, you’ll find that the weights move easily, and you finish the set feeling like you could do another rep — or another two, or even three. Those reps you could have performed (but didn’t) are not wasted. Remember: we’re trying to build you up, not break you down. Saving reps in the tank saves resources your body can use to recover. And by tracking the reps in the tank you have left every workout, over the course of several training cycles, you can better tailor your training to fit your individual recovery and strength curve. Here’s how it works: 1. After each set, evaluate how many more reps you could perform. Let’s say it’s your week of 2 reps, and after your first set, you really think you could have done 4. So you had 4 reps possible - 2 reps performed = 2 reps left in the tank. Record that number. Be honest about this! If you had to really grind through your last rep, don’t pretend that you could have done another — it might help your ego, but it will just hurt your progress in the long term. In that case, your reps in the tank is zero. 2. If, for whatever reason, you aren’t able to complete the scheduled number of reps in a set — even though you put in 100% effort — your reps in the tank will be a negative number. For example, if you were supposed to perform 315x5 and only get 4 reps, your reps in the tank is -1. Don’t stress about it, just write the number down and keep going. And that’s it! Your reps in the tank will become very important later, after you’ve completed a full 10-week cycle of standard program. For now, as long as you’re tracking your training, you’re good to go! 11. TRAINING STYLE Here’s the secret to all of this: You should almost always feel like you have more reps in the tank. Only in weeks 3 and 4 of block 3 should you feel like you’re pushing to your absolute limit. If you’re in week 2 or 3 of blocks 1 or 2 and you’re missing reps, you overestimated your 1RM. Knock it down by 10% and start over with week 1. In those last two weeks of block 3, take as long as you need between sets. Don’t rush yourself, but move quickly enough to stay warm. In all of your other training, move as quickly as you can between sets. One last bit of advice: training time is your time. Don’t waste it by chatting or messing around with your phone. If you’ve got lots of friends at the gym, that’s awesome, and you should absolutely enjoy spending time with them — but do it before and after your workout, not during. Stay focused on your work in the gym while you’re training. You get out of it what you put into it. The Offseason Program 25 CUSTOMIZING YOUR OFF SEASON PROGRAM After you’ve run through a full 10-week block of the standard program, you can adjust your training to make it your own. STOP. RUN THE STANDARD PROGRAM FIRST. Look, I get it. Training three days a week isn’t enough! You need to do front squats/cleans/pinkie-up tricep extensions/(insert favorite exercise here)! You can handle way more than 74% for sets of 5! But if you’re new to the program, then you’re not experienced enough to tinker with it. If you fuck with things too soon, you could hurt your progress or your body. Don’t come crying if you can’t follow the training as written for 10 weeks. Think Strong 27 OKAY, IT’S BEEN 10 WEEKS. NOW WHAT? MAKE IT YOUR OWN Glad you asked! Hopefully, after a full cycle through standard program — if you followed it exactly as written — you accomplished two things: 1. You added a good amount of strength to your squat, bench press, and deadlift. CHAPTER CONTENTS 1. ADJUSTING THE PERCENTAGES 2. ADDING A FOURTH DAY 3. ADDING VARIATION 4. CONDITIONING 5. PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER 2. You noticed some trends in your training log or things (percentages, exercises, whatever) that didn’t quite work for you. They were okay, but they could be better. Obviously, not everything about your training will have been perfect. No program is perfect, especially no offthe-shelf program, because of Principle #5: everyone is different. But the Think Strong method really shines because, if you track your training appropriately, it teaches you to customize your training to meet your individual needs. Think Strong 28 1. ADJUSTING THE PERCENTAGES use 85% on squats for triples instead of 87%. You’d still use 87% for bench press, assuming you had at least 1 rep left in the tank on every set for that day. The first and most important change you’ll make involves the percentages you use each week. You’ve probably noticed that they’re not nice, round numbers — you use 74% on week 1 of block 1, for example, rather than 75%. That’s not arbitrary — 74% is the percentage that works well for many, maybe most people — but not everyone. Maybe it’s a little heavier than you think is appropriate for week 1. Or maybe it’s a little too light (but probably not). Conversely, if you had any sets where your “Reps in the Tank” was 3 or more, the weight was a little too light. When you repeat the program for your second training cycle, increase the weight you use on those exercises by the percentage listed below. It’s usually better to increase the percentages very slowly, because oftentimes you might just have a really great day in the gym, and that’s not necessarily the best indicator of progress. You want to base your numbers off your average performance, not your absolute best. More likely, you found that some time around weeks 6-8 you really started to struggle. In these later weeks, you can begin to make changes that really make a difference in the last couple sessions of your training cycle. To do that, you’ll want to look back at your training log and identify the sessions where you were pushing yourself to the limit. Go check the “Reps in the Tank” column of your training log. If you had any sets in weeks 1-9 where your “Reps in the Tank” was 0, or you didn’t complete all the reps, the weight was a little too heavy. When you repeat program for your second training cycle, decrease the weight you use on those exercise by the percentage listed below. So, for example, let’s say that on week 6, you had 0 reps in the tank on your last set of squats. On your next time through the program, You’re only changing the percentages on your heavy days. On your light days, you will always use 80% of whatever you use on your heavy day. ADJUSTING YOUR PERCENTAGES If you have this many reps in the tank... Adjust your percentage for the week by this much. Less than 0 Subtract 2% 0 Subtract 1% 1-2 No change 3 or more Add 1% Customizing 29 4-DAY VARIATIONS Note that the weekly rep schemes for each exercise remain the same as in the three-day standard template. DAY 1 Variation # 1 Variation # 2 Squat & Bench Press DAY 2 DAY 3 DAY 4 Deadlift & Overhead Press Light Squat/Bench Press & Glute-Ham Raise Barbell Row, Chin or Pull-up, Reverse Hyperextension & Abs Deadlift & Reverse Hyperextension Light Squat/Bench Press & Abs Squat, Barbell Row Bench Press & Chin & Glute-Ham Raise or Pull-up Customizing 30 2. ADDING A FOURTH TRAINING DAY At some point in your training cycle, you may have found that your workouts really tended to stretch on, and on… and on. This is especially common once you reach very advanced levels of strength — just warming up to squat 600 pounds can take an hour or more. If any of your workouts lasted longer than 2 hours, you might benefit from splitting your training over 4 days instead of 3. Now, if your workouts take a long time because you’re wasting time chatting or fooling around, obviously, that doesn’t count. You don’t need an extra day, you need to quit being lazy. Let’s assume that’s not the case, and that you really do need to cut back on the time you’re spending each day in the gym. You have two choices: 1. Perform no assistance exercises on days 1-3, and instead group them all together on a fourth training day. FOUR-DAY SPLIT #1 ➡ Day 1: Squat and Bench Press ➡ Day 2: Deadlift and Overhead Press ➡ Day 3: Light work for the Squat and Bench Press ➡ Day 4: Barbell Row, Chin/Pull-Up, and Abs FOUR-DAY SPLIT #2 ➡ Day 1: Squat and Abs ➡ Day 2: Bench Press and Chin/Pull-Up ➡ Day 3: Deadlift, Overhead Press, and Barbell Row ➡ Day 4: Light work for the Squat and Bench Press Regardless of which option you choose, all of your training sets, reps, and loads stay the same as on the three-day split. 2. Split day 1 into different days. Of these, I prefer option #1, but both will work well. Regardless of whichever option you choose, you’re not adding any additional work to your program. You’re just dividing it over more days. Customizing 31 3. ADDING VARIATION Variation is a tricky subject. On the one hand, variety is the spice of life, and in training, it can help keep you motivated and help to address weak points. On the other hand, the best way to become a better squatter is to squat more — that is, you should train specifically for what you’re trying to accomplish. In many ways, specificity is the opposite of variation. You must find a balance between specificity and variation in your training: enough variety to keep you motivated but enough specificity to ensure you’re progressing as efficiently as possible. Fortunately, there are some variations of the squat, bench press, and deadlift that are extremely close to the standard competition lifts — so close, in fact, that I’ve found them to be very complimentary. Here are the best variations to help your competition lifts: your lagging muscles while maintaining a very similar movement pattern to your competition style. That last point is key, because it means that the gains you make using the variation are more likely to carry over to your competition style. Every powerlifter should at least try incorporating these lifts into a training program. Don’t rush into using maximal weights with any of these variations, or you’ll risk injury. Make sure to base your percentages for all your variations using your 1RM for that variation, not for the competition lift itself. For example, if I can bench 405 with a wide grip but only 365 with a close grip, then I will base my closegrip loads off of 365. SQUAT WITH WRAPS/SLEEVES Regardless of whether you squat with wraps or sleeves in competition, using the other variation in your training can be a big help. Both have their own advantages and disadvantages: • Squat in wraps (if you compete in sleeves) or in sleeves (if you compete in wraps) • Bench press with a close grip (if you compete using a wide grip) or wide grip (if you compete using a close grip). • If you’re a sleeved squatter, using wraps for overload can help you strengthen your core and feel more comfortable with heavy weights. • Sumo deadlift (if you compete with conventional) or conventional (if you compete with sumo) • If you use wraps in competition, squatting in sleeves can help strengthen your position in the hole and give your body a break from the pain and increased loads By training with these variations, you can bring up Customizing 32 of the wraps. I have also found that squatting in wraps tends to help if I’m experiencing any knee pain, but this is not the case for everyone. If you’ve never used wraps before, don’t rush into them. You’ll need to adjust to the discomfort and pressure of using wraps, and depending on your style of squatting, you may need wraps that provide support or wraps that provide rebound. Finding the right wraps and learning to use them will take a few weeks, so at first, use the same amount of weight with wraps as you would with sleeves. CLOSE- OR WIDE-GRIP BENCH PRESS Most people know that the close-grip bench press puts more emphasis on the triceps relative to a moderate-grip press; and that a wide-grip bench puts more emphasis on the chest. Using a style different from what you use in competition can help strengthen the muscles that don’t get recruited as fully in your competition style. Which one should you use for variation? • If your usual grip places your index fingers within a thumb’s length of the unknurled (smooth) section of the bar, you should use a wide grip for variation. Place your index fingers on the rings of the knurled section instead. • If your usual grip places your index fingers more than a thumb’s length from the unknurled section, you should use a close grip for variation. Place your index fingers within a thumb’s length of the unknurled section. Of course, a wider or closer grip will work your muscles in new ways. To avoid injury, whether you’re going from a close grip to a wide grip or vice versa, I recommend moving your grip by a maximum of one thumb’s length per workout. If you’re starting with a very wide or narrow grip, it may take two or even three workouts to find your perfect variation grip. SUMO OR CONVENTIONAL DEADLIFT There’s not much to say here: the two different styles are nearly perfect complements. Conventional deadlifters often have a relatively strong back and legs, and weaker hips; and sumo deadlifters often have stronger hips and a weaker back. Training the opposite style can help bring up your lagging muscle groups. However, just like with the other variations, you need to ease into the transition. Sumo especially can place a lot of strain on the hips and groin, so if you usually pull conventional, start out with a very narrow sumo Customizing 33 stance, with your feet just outside of your arms. Every workout, you can move your feet out by a few inches until you find a stance that’s most comfortable for you. INCORPORATING VARIATION Just as there are many different variations of lifts, there are also many different ways to incorporate variations into your training. Here’s my preferred method: • • • For lower-body training — both the squat and the deadlift — use your variation for the first week of each block, and use your competition style for the second and third weeks. For the bench press, use your variation for your light day each week, and use your competition style for your heavy day. During meet prep, only use your competition style. Obviously, when you introduce variations, your programming will get much more complicated, very quickly. For that reason, it’s best not to introduce variations until after you’ve completed at least one full training cycle, and are very comfortable with how the standard program works, and know how to alter your percentages and training days to fit your body. 4. CONDITIONING Conditioning is a doubled-edged sword for powerlifters. On the one hand, it will make you leaner, tougher, improve your work capacity and cardiovascular ability, and make you feel better overall. On the other hand, it will may significantly detract from your recovery — energy you could have spent lifting and getting stronger. Some benefits of conditioning: • • • • • Decreased DOMS Better able to take short rest periods in the gym Better able to do high-rep sets Fat/calorie burning Improved mental strength (from challenge workouts) or chance for relaxation (for easy ones) So you have to find a balance between doing too much conditioning, and not enough. Until I decided that I wanted to be an elite lifter, I did a lot of conditioning: intervals on the Airdyne, Prowler pushes until I nearly passed out, hill sprints, even Crossfit metcons. I enjoy challenging myself, and so I enjoy conditioning, but when I cut all that stuff out that I quickly added about 100 pounds to my powerlifting total. Now I do low-intensity, low-impact cardio workouts on the elliptical (about an hour a week total). Customizing 34 That’s my balance. You have to find your own sweet spot for conditioning — but fortunately, that’s fairly easy for most people. We’ll get into programming later in this chapter, but for now, if you’re not already doing any conditioning work, just plan to start with one easy workout per week, and gradually increase that amount until you find the amount that’s right for you. drawbacks. LISS workouts lasting 20-30 minutes typically have no drawbacks, as long as you choose some lowimpact activity that doesn’t stress your joints. CHALLENGE WORKOUT SUGGESTIONS CONDITIONING WORKOUTS When it comes to conditioning for lifting, you have two choices: 1. Low intensity, steady-state training (LISS) 2. High intensity interval training (HIIT) LISS workouts are your typical cardio bunny training: some type of steady activity that gets your heart rate elevated to about 60-80% of your max, and doesn’t take too much thought or effort. HIIT workouts, on the other hand, require you to go all-out for a short period of time, followed by a short rest period, repeated for 15-20 minutes total. Low intensity interval work just isn’t hard enough to produce any benefits, and high-intensity steady-state work will destroy your lifting progress — it’s just too much to recover from. Generally, HIIT will have more noticeable benefits than LISS for lifters, but it will also have more noticeable 50/20 Sandbag: You’ve got twenty minutes to complete 50 reps, any way you can. Generally, you’re best off choosing a weight that you can do 10-15 unbroken reps with, and then digging deep to get through the rest. You can either shoulder the sandbag, or clean and press it (obviously use a lighter weight for the clean and press workout). Sled Suicides: Load a sled or Prowler to 100 pounds. Sprint 25m forward, then immediately turn the sled around and sprint 25m backward. No rest between “sets.” You can repeat this workout and try to beat your best time. Hill Sprints: Wearing a weighted vest, sprint 200 meters every 2 minutes for 10 minutes total. So if your sprint takes 30 seconds, you get 90 seconds rest. If it takes 60 seconds, you get 60 seconds rest. Find the steepest hill you can for these! Customizing 35 CHALLENGE WORKOUTS Sometimes, you’ll just feel like going hard on the conditioning. Maybe you’ve had a lot of stress outside of the gym; or maybe you have some extra energy to burn. Either way, if you’re in the offseason, you can afford to incorporate some “challenge workouts” into your training — although not on a regular basis, and never more often than once a week. If you do them too often, don’t be surprised if your lifting performance suffers. Challenge workouts stress your lungs and mind to the max, and you can get afford to get creative with them. INCORPORATING CONDITIONING INTO YOUR PROGRAM interfere with your training. 4. If your goals include weight loss or conditioning for its own sake, you can continue adding conditioning sessions throughout the week, including ones on the same day as your lifting. I recommend always performing conditioning after lifting. 5. Once you’ve incorporated more than two conditioning workouts per week, you’ll probably notice that your lifting suffers a bit. It’s up to you to find the right tradeoff between the two. 6. If you decide to incorporate any challenge workouts, do them instead of, and not in addition to, one of your already-scheduled conditioning sessions. Just like with all the other customizations to your program, you need to incorporate conditioning workouts slowly. Here’s the process I recommend: 1. Start with one LISS workout per week, on a day when you’re not training with weights. 2. If you find that conditioning benefits your recovery, add in a second LISS workout per week. 3. If you continue to notice improved recovery, try switching one of your LISS workouts to a HIIT workout. Schedule the HIIT workouts soon after one of your two heavy training days, so that it doesn’t Customizing 36 5. PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER By now you can tell that there’s plenty of ways to customize the Think Strong method and make it uniquely your own. Don’t try to make all of these changes all at once. That’s a sure-fire route to frustration, because inevitably, some of the changes won’t work all that great. If you make lots of changes all at once, you won’t be able to figure out which ones worked and which didn’t. So instead, take it slow! Your first cycle should have proven that the standard program works, so there’s no rush to mess with it. Start by just adapting the percentages based on your last cycle, and run that for ten weeks and see how it works for you. If it helps, then keep adjusting your percentages each block. If it doesn’t help, then drop it. Go back to the standard percentages, and instead experiment with adding in variations. Again, there’s no rush. Your goal is to continue making progress for as long as possible, so only make (small) changes when progress slows or stops. If a change doesn’t work for you, don’t stress about it — just go back to what you know does work, and try changing something else. You’ll probably notice that this chapter is more open-ended than the offseason or meet prep chapters. At first, that might seem frustrating, but try to reframe that frustration: once you’ve started to customize your program in the slow, methodical trial-and-error process described in this section, you’ve freed yourself from constantly following cookie-cutter programs and from using ineffective or poorly-designed ones. That’s a big step on the road to becoming an elite lifter. That said, there is a sample offseason program on the next few pages that incorporates some of the variations discussed in this chapter, just to give you an idea of what your training might evolve into over time. If you’re patient, take the time to learn what works for body, and train hard, you can use this process for years with great results. So get to it! Customizing 37 Week 1 VARIATION 1 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Exercise Work Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 4 5 74 Barbell Row 3 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Bench Press 4 5 74 Chin/Pull-Up 3 10 — Deadlift 4 5 74 Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Squat 5 5 59 Close-Grip Bench Press 5 5 59 Abs 3 10 — Squat with Wraps 6 2 85 Barbell Row 4 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Bench Press 6 2 85 Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Sumo Deadlift 6 2 85 Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Squat with Wraps 5 2 68 Close-Grip Bench Press 5 2 68 Abs 4 10 — Squat with Wraps 4 3 85 Barbell Row 5 10 — Glute-Ham Raise 5 10 — Bench Press 4 3 85 Chin/Pull-Up 5 10 — Sumo Deadlift 4 3 85 Reverse Hyper 5 10 — Squat with Wraps 5 3 68 Close-Grip Bench Press 5 3 68 Abs 5 10 — Week 2 Day 1 Day 2 Block 1 Day 3 Day 4 Week 3 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Remember, these are just suggestions! Your own customized program will probably look a bit different. Week 1 Day 1 Day 2 VARIATION 2 Exercise Work Sets Reps Load (%) Squat 4 5 74 Bench Press 4 5 74 Deadlift 4 5 74 Overhead Press 4 5 74 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Conditioning: High Intensity Squat 5 5 59 Bench Press 5 5 59 Glute-Ham Raise 3 10 — Barbell Row 3 10 — Chin/Pull-Up 3 10 — Reverse Hyper 3 10 — Abs 3 10 — Day 6 Conditioning: Low Intensity Week 2 Day 1 Day 2 Block 1 Squat 6 2 85 Bench Press 6 2 85 Deadlift 6 2 85 Overhead Press 6 2 85 Conditioning: High Intensity Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Squat 5 2 68 Bench Press 5 2 68 Glute-Ham Raise 4 10 — Barbell Row 4 10 — Chin/Pull-Up 4 10 — Reverse Hyper 4 10 — Abs 4 10 — Day 6 Conditioning: Low Intensity Week 3 Day 1 Day 2 Squat 4 3 85 Bench Press 4 3 85 Deadlift 4 3 85 Overhead Press 4 3 85 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Conditioning: High Intensity Squat 5 3 68 Bench Press 5 3 68 Glute-Ham Raise 5 10 — Barbell Row 5 10 — Chin/Pull-Up 5 10 — Reverse Hyper 5 10 — Abs 5 10 — THE MEET PREP PROGRAM When you’re ready to test your limits, switch from the offseason program to this one. Again, it’s a simple program, but the heavier weights will push you to your limits and prepare your body for a 1-rep max attempt. THINKING STRONG ABOUT MEET PREP 1. MEET PREP APPROACH CHAPTER CONTENTS LOREM IPSUM 1. MEET PREP APPROACH 1. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur. 2. ATTEMPT SELECTION 2. Nulla et urna convallis nec quis blandit 3. THE MEET odio mollis.PREP CYCLE 3. Sed metus libero cing elit, lorem ipsum. 4. ACCESSORY WORK Adip inscing nulla mollis urna libero 5. DELOADING blandit dolor. 6. ADVICE 4. MEET LoremDAY ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur. 5. SOME Sed metus libero cing elit, lorem ipsum. 7. FINAL THOUGHTS Quis que euismod bibendum sag ittis. 6. Fusce leo erat, tincidunt nec posuere sit amet, condimentum id dolor. 7. Duis faucibus adipiscing blandit. In the offseason, you’re trying to build momentum. During meet prep, you’re trying to use that momentum to peak. That means you’ll be pushing harder on your main lifts, and cutting back on any extraneous stuff like accessories and conditioning. However, pushing harder means that meet prep is more stressful, both physically and mentally. Your goal during meet prep is to manage that stress while still completing your workouts as scheduled. Many, many people get overwhelmed by the increased stress and either give up or back off. Your ability to push through tougher training sessions, without getting injured or burnt out, will determine your overall success in powerlifting. It’s generally a good idea to schedule your meet for a time when you don’t have a lot of other stressful or significant activities going on. Conversely, the week Think Strong 41 after peaking is an ideal time for a deload, if you’re starting to feel banged up or run down. Also, keep in mind that although this section (and book) is about training for a meet, you don’t have to compete in a formal meet if it’s not right for you. You can just test your squat, bench press, and deadlift in the gym — and you can even test each one on a different day during a single week, if you like. The important thing is that at some point, you do test your limits, so that you have an objective measure of 1RM strength to base your next training cycles off of. your current 2, 3, or 5 rep PRs, and you’re all set: those are perfect goals for your test day. Otherwise, things get a little more complicated. Here are some things to consider when you’re setting goals: • Your current training maxes. Obviously, this is the biggest consideration. Planning to beat your bests by 100 pounds is unrealistic — you’ll probably just hurt yourself trying. Planning to just “chip” your PR (by adding just 2.5 or 5 pounds) is an equal waste of time. If it takes you 10, 12, or even 16 weeks of training to add 5 pounds to your best, you need to seriously reevaluate your training. A good compromise is somewhere around a 5% improvement on your current best. So if the most you’ve ever squatted for one rep is 400 pounds, 420 might be a good number to have in mind going into meet prep. • Milestones. When you’re coming up on a big number — whether it’s 300, 400, 500 pounds; or some kind of record — it seems like a very obvious goal. And those types of goals can be very motivating, which is great. But, on the other hand, it’s easy to get anchored to those numbers and either A) assume they’re an appropriate goal without really thinking them through or B) becoming obsessed with them and making them out to be a bigger and more intimidating thing than necessary. Neither situation is ideal. To avoid these pitfalls, make sure you consider whether that big number is really reasonable. If you just hit a 300- 2. ATTEMPT SELECTION Once you’ve selected a date, either for a full meet or just to test your 1-rep maxes, you need to determine your goals for the squat, bench, and deadlift. This must be the first step, because all of your meet prep programming will be based on those numbers. Setting goals is tough, though, because it requires that you find a balance between being realistic and aggressive. If you set overly conservative goals, you won’t push hard enough to reach your potential, and if you push too hard, you’ll fall short and get discouraged. You need a starting point, and if you’ve ever tested your 1-rep maxes before, then you’ve already got one. If not, just use a 1RM calculator like the one in the Tools tab of the Think Strong spreadsheet to estimate them based on The Meet Prep Program 42 pound bench at your last meet, then yeah, 400 is the next big marker, but you’re probably not going to jump 100 pounds in just one meet. On the other hand, if you squatted 496 at your last meet, don’t make 501 your goal for the next one — that’s a waste of a training cycle on low expectations, and can actually make the 500-pound marker more imposing compared to a goal of 525. • The competition. Winning is always a great goal, because competition often brings out the best in people. Plus, if your goal is to win, then you’re not going to get fixated on any specific numbers. On the other hand, winning is only a reasonable goal if you have a fair idea of your competition and are strong enough to actually pull it off. If that’s the case, you’re probably already a fairly advanced lifter, and you should be pretty used to setting your own goals. But it’s still helpful to keep winning in mind! If these ideas aren’t enough to get you started in the right direction, check out the FAQs section in the Appendix. It has a bit more on the theories behind goal setting that might help you out. WORKING BACKWARDS TO YOUR GOALS Once you’ve picked goals, it’s easy to work backwards to determine your attempts: 1. Your third and final attempt of each lift will be your goal. 2. Your second attempt should be somewhere around 94-96% of your third attempt. 3. Your opener should be somewhere around 85-90% of your third attempt, and a weight that you are comfortable hitting any day of the week, regardless of how you feel. If 85-90% of your third attempt is not an easy, guaranteed lift, than your goals are probably too aggressive, and you need to adjust them downward a bit. Now, if you’re going for an informal test day, and not a meet, you have a little more flexibility, since you’re not limited to three attempts. In that case, a very similar process will work: 1. Take your first two heavy singles exactly as you would in a meet: 85-90% and 94-96% of your goal, respectively. 2. After your second heavy single, you’ll begin to attempt to set new personal records. I recommend beginning with a small PR — 5 pounds is a great number. So your third heavy single should be 5 pounds over your 1RM. (If your second heavy single was a PR, then just start going up in 5 pound jumps from there.) The Meet Prep Program 43 3. If your third single was an all-out attempt, stop there — you’re done. 4. If your third single wasn’t an all-out attempt, add 5 or 10 pounds and attempt another single. 5. Continue doing taking progressively heavier singles, adding 5 or 10 pounds each set, until you either (A) miss or (B) feel like there’s no way you could make a heavier lift. If you’re writing your own program, you should incorporate the “working backwards” method for all of your meet-prep training. 3. THE MEET-PREP CYCLE The meet prep cycle takes a working-backwards approach, too, but in a slightly different way than most programs. Though the entire 2-block, 6-week program will be difficult (physically and mentally), the first block is a bit more challenging than the second. This accomplishes two things: first, your most difficult training takes place before the mental stress of an upcoming meet really kicks in; and second, your body has more time to recover from your heaviest work, so you are less reliant on timing a perfect deload to peak properly. Keep in mind, this is strictly a peaking program. You should start meet prep after you’ve done enough cycles of the offseason program that you: 1. Feel physically and mentally fresh 2. Believe that you have gained strength compared to your previous bests, and are ready to translate those strength gains into a new one-rep maximum. For example, let’s say you competed on January 1, and squatted a PR of 400 pounds. Then you took a week off to recover and, once you felt well-rested, began the offseason program. Now it’s April 1, and you’re regularly performing squats with over 375 pounds for doubles and triples. You’re in a great place to start the peaking program, and can feel confident that you’ll squat somewhere around 420 pounds at meet in mid-May. On the other hand, if you’re struggling with squatting 350 for sets of 2 or 3, you haven’t really gained any strength, and you need to spend some more time in off-season training before you try to peak. I also advise that you take a brief deload before beginning meet prep — you’ll need to be fresh to complete the desired work. Perform the deload exactly as described in Chapter 1.9. You’ll deload the week before the meet, too, so you need to plan for 8 total weeks of meet prep — not 6! When you’re ready to get going, here’s how the peak works. Note that your 1RM should equal what you are currently capable of, not what you hope to lift on your final attempt at the meet/test day. You’ll still perform the standard ramp-up sets before the work sets listed in the table. The Meet Prep Program 44 DAY 1: SQUAT DAY 2: DEAD DAY 3: BENCH Reverse Hyperextension & Abs: 3 sets of 10 Glute-Ham Raise & Abs: 3 sets of 10 Chin or Pull-up & Abs: 3 sets of 10 Week 1 2x3 with 88-91% of 1RM Week 2 2x2 with 92-96% of 1RM Week 3 4x1 with 95-101% of 1RM Week 4 2x3 with 85-88% of 1RM Week 5 1x3 with 93% of 1RM Week 6 1x2 with 98% of 1RM The Meet Prep Program 45 WEEK 1 2x3 with 88-91% of 1RM We start off with what should be a new 3RM and a lighter backoff set. Your focus this week should be on technique: don’t let it break down even though you’re using more weight than you have in a few months. The weights should be light enough that this feels manageable, but don’t overreach in week one. You’ll need your energy for the rest of the peak. For this same reason, it’s really important that you deload between the offseason and meet prep, as explained in the previous section. WEEK 2 2x2 with 92-96% of 1RM Week two follows with a new 2RM, which may be the most physically demanding week of this first block. Again, you’ll have a lighter backoff set after your top set, but your overall volume is still very low at this stage. WEEK 3 4x1 with 94-101% of 1RM This may well be the hardest week of the entire peak from a mental perspective, because you’ll be using a weight that you have never handled before. Don’t be surprised if your form begins to deteriorate a bit on the heaviest single this week. That’s okay, as long as you’re not putting yourself in a position for injury, and you still adhere to the technical requirements of the lift. Don’t cut depth on your squat or shorten your bench pause just to complete the prescribed loads — you’re only selling yourself short and setting yourself up for disappointment at the meet. The Meet Prep Program 46 WEEK 4 2x3 with 85-88% of 1RM This is a relatively lighter week — almost a semi-deload before the final push to the meet. Use this as an opportunity to relax a bit, and to hone your technique to the utmost. You may want to perform just one triple (instead of two) if you’re feeling especially beat up or are already very confident in your technique. WEEK 5 1x3 with 93% of 1RM The triple on week five will again be a new 3RM, and you should be able to complete it with just a little room to spare. Don’t miss any reps from here on out. If you’re not confident in your ability to complete all three reps, either drop the weight 1-2% from whatever is planned, or perform only two reps on that set. If you don’t complete the triple, however, it’s probably a good idea to lower your planned attempts a little bit. Remember, you still have ramp-up sets, so this week and the next are not as very low-volume as they might seem. WEEK 6 1x2 with 98% of 1RM This is it: the end of the meet prep. You’ll be setting a new 2RM instead of singles so that you won’t run the risk of missing any reps; again, if you’re not confident of completing it, drop the weight or perform two singles instead. If that’s the case, however, you should again adjust your expectations for meet day. As soon as you complete week six, it’s time to rest and recover! The Meet Prep Program 47 4. ACCESSORY WORK You’ll notice there’s very little programmed accessory work in the meet prep phase. I strongly recommend that you do perform accessory work, but that you treat it as preventative maintenance rather than strengthening exercise. You only have a limited amount of physical and mental energy available for training, and during meet prep you need to direct that entirely at the squat, bench press, and deadlift. So don’t worry about adding weight or volume to the reverse hyperextension, glute-ham raise, chin or pull-up, and abdominal work while you’re prepping for a meet. Just use a light weight and focus on using your muscles in the correct pattern. 5. DELOADING You never want to go straight from heavy training into a meet: your body needs a bit of time to compensate from the stress of all that work before you can perform your best. The amount of deloading you’ll need depends on your training volume; folks who aren’t used to a lot of heavy work or who rely on high-volume loads close to a meet need more deload time than those who take a more moderate approach. In most cases, though, a oneweek deload is about right. During that deload week, you’ll have just one heavier workout, and it should be five days before the meet (so if the meet is on Saturday, take this workout on Monday). You will start with squat: warm up and perform 3-5 singles with whatever you’ve planned as your last warmup before your opening attempt (92-93% of your opener is a good number to have in mind). Take a short break (about 10-15 minutes), and move to bench. Warm up and perform 3-5 singles with just a bit less than your opening attempt (97-98% of your opener). Finally, take 3-5 singles with 50% of your max deadlift. That’s it — don’t do any more work here. Three days before the meet (so Wednesday, if you’re competing on Saturday), you can take about 40-50% of your max squat and bench press for 1-3 sets of 1-3 reps. This is just to help you stay loose. You can also perform some very, very light accessory work for the upper back, biceps, abs, and calves if you like. The day before the meet (after weigh-ins, if you have a 24hour weigh-in), perform some very, very light squat, bench press, and accessory work for the upper back and abs. For reference, my best squat in training is over 800 pounds, and I would use 135 pounds for a few sets of 5-10 at this workout. There’s nothing wrong with just taking the empty bar, either. On the other days, stay out of the gym, but you can perform some very, very light cardio (walking on a flat surface, etc.) and gentle stretching and mobility work to stay loose. The Meet Prep Program 48 6. MEET-DAY ADVICE a friend to chat with, or even a book to distract yourself for a short while can all help. Describing how to compete in strength sports could be an entire book in itself. In fact, Bill Starr’s Defying Gravity is a book about exactly that, and I strongly recommend reading it. But if you’re just getting started, a little advice can go a long way. Some common competition issues: Again, you don’t want to try anything unusual on meet day, so give all of those a shot in the gym well before you bust them out at a competition. In fact, you might want to start trying different mental strategies in the offseason, so by the time meet prep rolls around, you already know what works for you and you can practice it during heavy lifting. MINDSET A strong mindset is crucial to peak performance. But it’s often difficult to stay in a good headspace in highstress situations, like a meet. So when you start your meet prep cycle, make sure you include some mental training, too — the more you can understand your mind and how it affects your body, the better you’ll be able to handle the unexpected when it arises. Basically, you want to keep the same mindset at the meet as you would during a regular day at the gym. You perform your best when you keep your heart rate and breathing pattern very close to how they usually are when you train; major variations (either increases or decreases) can negatively impact both your physical and mental abilities. Of course, very few if any people are calmer at a meet than in the gym, so you really only need to plan for getting too nervous or psyched up. Have some way of calming yourself down: a breathing or meditation routine, CUTTING WEIGHT I think one of the biggest misconceptions regarding weight cutting is the idea that it needs to be some extreme, life-threatening endeavor that risks destroying not only your performance but also your long-term health. In reality, those type of weight cuts happen for one of two reasons: 1. Highly-driven, elite athletes attempt to cut an unreasonable amount of weight without any regard for their health, or 2. People are lazy and don’t prepare well enough in the offseason, so they have to play catchup the week before a competition. As you might have guessed, the second scenario occurs far more often than the first. The Meet Prep Program 49 That said, cutting weight is still a fairly involved process, and even if you’re an appropriate body weight and body fat percentage before starting the water cut, you still need to treat the last week before a meet very carefully. Here is a very general guideline for a water cut for a Saturday meet with 24-hour weigh-in. SUNDAY Began to decrease my food volume slightly, by reducing vegetable intake, and increase sodium intake quite a bit (just salting your food heavily is fine). Drink 2.5 gallons of tap water. Don’t be surprised if you body weight increases, even significantly, during the water and sodium load. MONDAY Decrease sodium significantly, and drink 2.5 gallons of tap water. TUESDAY Eliminate sodium intake entirely, and drink 2.5 gallons of distilled water. You may want to take a very light, highrepetition training session on Tuesday. WEDNESDAY Continue with zero sodium intake, eliminate all carbohydrates, and increase water intake to 3.5 gallons of distilled water. THURSDAY Upon waking, take 1,000 mg of dandelion root extract, 100 mg of potassium, and 200 mg of caffeine. Twice more during the day, take 1,000 mg of dandelion root and 100 mg of potassium. You will eliminate water intake depending on how much weight you need to lose. If you are cutting 5-7% of your waking body weight, you can drink half a gallon of distilled water upon waking and drink no more during the day. If you are cutting less than 5%, you can drink a full gallon of distilled water between waking and 3 PM (assuming a 9 AM weigh-in). FRIDAY If you are cutting a significant amount of weight, you may need to sweat in a hot bath even after the water and sodium load. I strongly suggest not sweating until the day of weigh-ins. You should minimize the time spent at weight, even if that means waking up at 5 AM to sweat. The easiest way to sweat is in a hot bath (as hot as you can stand), Alternate 15 minutes in a hot bath with 15 minutes of cooldown until you make weight. Do not drink water during the breaks. You may find it helpful to spend that time under a fan chewing ice chips if necessary. Rehydrating correctly after making weight is crucial to a good performance the next day. Your first priority should be to consume some type of electrolyte fluid with some carbohydrates, like Pedialyte or diluted Gatorade. Your first solid-food meal should contain some easily digestible carbohydrates; like fruit with salt, but make sure The Meet Prep Program 50 whatever you choose is easy on the stomach. It’s beneficial to wait a short while after you start drinking to begin eating. Thirty to 45 minutes after that first meal, you can eat something more substantial with some protein content. Whatever you choose should be high in carbohydrates and salt, low in fat, and with a moderate amount of easilydigestible protein. It should also be a food that you eat regularly! If you upset your stomach at this point, you’re just going to make the rehydration process more difficult. Throughout the rest of the day, you need to continue to eat small meals every two hours, and to consume at least another gallon of water. Your meals from this point on should be balanced in carbohydrates, protein, and fats, and high in salt. Try to go to bed on Friday weighing the same as you did on Wednesday night. WHEN TO ARRIVE It’s important to consider when you’ll arrive at both the meet venue and the host city. If you’re traveling a long distance (over 250 miles or so), you’ll probably want to arrive the day before weigh-ins to give yourself time to adjust and make sure you’re not exhausted if you need to cut weight. If you’re flying to the meet, you may want to give yourself 2 or even 3 days to adjust, depending on the time change. Flying can affect your body in ways you might not expect, so best to give yourself some time to settle. Of course, hotel fees add up, so don’t pressure yourself into staying longer than absolutely necessary. And if you are cutting weight, make absolutely sure to call ahead and check whether there is water hot enough to sweat in, or I promise you will regret it (I’ve made this mistake more than once)! Once you’ve arrived, try to keep as close to your normal routine as possible. Get up and go to sleep at the same times, eat the same foods, and do more or less the same amount of physical activity in your day. If you have a desk job and spend a whole afternoon walking around a new city the day before a meet, your performance will probably suffer. That said, again, it’s a balance — if there’s a really cool opportunity that won’t be available after the meet, take advantage of it! On the meet day itself, arrive at the venue on time. There’s really no need to show up early unless you’re in the very first flight — I’ve only once been to a meet that started exactly on time. If you have a two-hour (rather than 24-hour) weigh-in, you might want to arrive 10-15 minutes early just in case the meet director is feeling generous and starts early (not likely, but you never know). The Meet Prep Program 51 WARMING UP You want to be especially careful about warming up on meet day, for a couple of reasons. First, it’s often colder in the meet venue than you might be used to, and you may have less access to the normal equipment you use to warm up. Second, you’ll be performing minimal reps with maximum weight, which is a good combination for injury. To prevent that, make sure to dedicate plenty of time to a general warmup as described in the FAQs sections. In addition, you may find it beneficial to take some extra precautions. Again, you never want to try anything on meet day that you’ve not used before in training, so give all these ideas a shot in the gym before you try to implement them at a meet. 1. Try wearing a pair of neoprene pants, to give your lower body a little extra warmth and support. These pants are a bit thick, but they won’t restrict your movement nor add any weight to your lifts, so they’re a great tool. They make it much easier to warm up and stay warm during your session. If you find that they throw you off at all, just wear them for your lighter warm-ups, and take them off for your work sets. Personally I think they’re really comfortable but they can ride up a little and get in the way of your belt. areas. I like to get my shoulders, elbows, hips and knees. Again, this will help with blood flow and warming up, and can also help you to activate muscles that might not be firing in the right way on a particular day. You might not notice any benefits at first, but over time, it makes a difference. I prefer to use capsaicin, but some people don’t like it because it can get very hot once you start sweating. Otherwise, menthol (Icy Hot or Tiger Balm) works well, too! 3. Finally, consider including some extra warm-up/ activation exercises in addition to your regular warmup and mobility routine. As long as you put the time and care into warming up properly, you can be confident that you’re doing all you can to protect your body and perform at your best. 2. Use some type of liniment before you begin your warmup, especially on any tight or troublesome The Meet Prep Program 52 WHAT TO EAT Meet-day nutrition probably isn’t quite as important as rehydrating after weigh-ins, but it’s close. So many lifters fail to plan for that, and just eat whatever happens to be available. That’s a terrible decision because it’s such an easy way to blow all the hard work you’ve done up to that point if you happen to eat something that upsets your stomach. Instead, bring familiar, easy-to-digest food sources that are high in carbohydrates and moderate in fat and protein. Your goal on meet day is to eat and drink as much as you can without feeling sluggish. This is not the time to count calories: the more you eat, the better you’ll perform. Keep in mind that there probably won’t be any refrigeration available, so bring your own cooler or choose foods that don’t need to be refrigerated. Also make sure to keep some type of sugar readily available. Gatorade, candy, or glucose tablets are all good choices. If you end up overreaching on an attempt and miss or really struggle, get 75-100 grams of sugar in ASAP (50 if you’re a smaller person). It’ll help you recover quickly enough to be ready for the next event. 7. SOME FINAL THOUGHTS Powerlifting meets are mentally and physically stressful, and demand a significant amount of dedication and planning. That’s exactly why you should do one. Any form of competition has a lot of benefits, but the powerlifting community is, with few exceptions, something very unique and very valuable. Entering a meet is by far the quickest and easiest way to become part of that community. You’ll meet new people, make new friends, and grow as a person just by getting involved. Competing is a good practice in setting goals and meeting deadlines; and it challenges you to overcome adversity and the inevitable setbacks. At the same time, before you invest in the peaking process, make sure that competing is the right choice for you, that it comes at the right time, and you’re doing it for the right reasons. If you feel pressure to compete — either internal or external — you’ve no chance to really perform at your best. Instead, compete only if it’s something you’re excited about! You’ll need that excitement to fall back on if your motivation wanes; and besides, powerlifting will never pay your bills. Do this sport because you enjoy it, and never for any other reason. Good luck, and Think Strong. The Meet Prep Program 53 APPENDIX If you’ve been reading closely and gotten this far, you probably have some questions. This Appendix will try to answer most of those. Pay special attention to the Technique section! Good technique will keep you from getting injured, and that’s the number-one secret to long-term success in powerlifting. FAQS FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS WHY ISN’T MY FAVORITE LIFT IN THE PROGRAM? Because you don’t need to do front squats, incline bench, deficit deadlift, or pinkie-up curls all the time. There’s nothing wrong with having a favorite lift, but oftentimes our favorites are just the things we’re good at. If you’re training a lift that (A) isn’t one of the competition lifts and (B) you’re already good at, you’re just wasting energy. A big part of this program is conserving energy, so that you can make progress for as long as possible. If you’re really struggling with the idea of omitting a particular assistance lift, ask yourself this: has the lift directly contributed to increases in your squat, bench press, or deadlift? If the answer is no, then you don’t need to do that exercise. If it’s yes, then fine — add the exercise in as a variation the next time your start a new training cycle. Think Strong 55 I NEED TO TRAIN FOUR DAYS A WEEK! minding your exercise technique. If you’re slacking off on your training, your results won’t be optimal. • Do you need a deload? The flip side of not training hard enough is training too hard for too long. If you’re suffering from frequent aches and pains, a poor appetite, lack of sleep, or illness, you may need to take a deload week. See Chapter 2 to learn how to implement a deload without detracting from your longterm progress. • Did you choose your one-rep maxes appropriately? If you’re struggling in the first block, your 1RMs are too high — you should drop them by 10% and start over with week 1. • If you’re struggling in block 3, that’s totally normal. Just keep pushing through, and take a deload the week before testing your 1RM. You’ll come back stronger and smash PRs. No, you don’t. See above. Now, if you need to train four days per week because your workouts are taking too long, that’s a separate issue; see Chapter 3 to learn how to adapt the program to accommodate longer workouts over more training days per week. WHAT HAPPENS IF I HAVE A BAD WORKOUT? Not a thing. If you can’t complete the prescribed reps on any given day, just make sure to record your negative reps in the tank, and then move on to the next exercise or next training day. BUT WHAT IF I HAVE SEVERAL BAD WORKOUTS IN A ROW? This is a trickier question, and there are lots of possible solutions. Be honest with yourself: • Are you training hard enough? “Hard training” means staying focused and aggressive in the gym, and preparing for your workout by warming up appropriately, getting good nutrition and rest, and Appendix 56 HOW SHOULD I WARM UP? You have two overarching goals for your warmup: to prepare your body and your mind for heavy training. Physically, you need to increase blood flow and body temperature; activate the specific muscles you’ll be training; and protect any weak or troublesome areas. Mentally, you need to practice the appropriate movement patterns with light weights to sharpen your technique and build confidence for your working sets. To do that, start with a general cardiovascular warmup. You can choose pretty much any activity, as long as it’s low-impact and will allow you to break a sweat in 3-5 minutes. Then, you’ll want to address any areas that hurt (or have been hurt in the past) or lack range of motion. I’ll be honest, I often use foam rolling for this purpose, but it’s not ideal: it might provide some temporary relief, but it can also make it harder to activate the muscles you’re working — so think about it before you just jump on the roller. Really, any mobility practice that you find to be effective is a good choice here — and there have been many, many books on that topic, so I’ll leave it up to you to find methods that work. Finally, you need to “wake up” the muscles you’re training with activation exercises. Perform these using a very light weight (or bodyweight), for sets of 10-20 with little or no rest in between. Your goal is to feel the muscle working — to turn on the mind-muscle connection. Again, any movement that you feel helpful is the right choice here, but in case you need a place to get started, here are some suggestions: And, lastly, you need to get your mind right. Many lifters like visualization for this purpose: a mental walkthrough of the workout you’re about to do. “Rehearsing” in this way can help you to focus and boost performance during the workout. Personally, I find that visualization tends to create a sort of artificial pressure to meet some imagined version of a perfect workout. I prefer to meditate, or practice breathing exercises, before I lift. Being present in the moment, rather than thinking ahead, can have the same benefits of visualization. Try both, and stick with what works — or find your own mental warmup! WARMUP SUGGESTIONS CARDIOVASCULAR SQUAT/DEADLIFT BENCH PRESS Incline walking Leg extension/curl Rear delt row Prowler push Reverse hyper Flye Sled drag Wall sit Push up Stationary cycling Goblet squat Dumbbell pullover Pistol squat Appendix 57 WHAT IF I CAN’T DO CHIN OR PULL-UPS? It depends. If you’re not strong enough to do them, you have two options: • Lightened chins using a band. Take a mini band, loop one end around the chinning bar, and put the other end around one or both of your feet. The band will lighten the load at the bottom (hardest) part of the movement, allowing you to concentrate on using the correct muscles. • Lat pulldowns. Obviously, the lat pulldown is a similar movement, but without the requirement that you use at least your bodyweight, and without requiring you to use quite as many stabilizing muscles. If you can’t do any chins, or can’t do enough to train them progressively, train the pulldown instead until you can use about 110% of your bodyweight for 10-12 reps, and then give chins another try. If you can’t do them because of some preexisting injury or lack of mobility, you can swap them out for lat pulldowns or seated rows. Make sure you address the underlying issue, though, so that it doesn’t become an even bigger problem. I’M STRUGGLING WITH GOAL SETTING AND ATTEMPT SELECTION. WHAT SHOULD I DO? If you’re struggling with goal setting, you’re probably frustrated, because everyone knows the benefits of setting good goals. You may even have read about S.M.A.R.T. goals, for example, which provide straightforward, easy-to-understand markers of progress. It's true that having goals can keep you focused, efficient, and even motivated, especially when you're a beginner. Goals are important, but once you pass that beginner stage, progress isn't linear anymore, and focusing on an end goal can often become limiting. How many times have you set a goal for a daily workout and gotten frustrated when you can't lift as much as you expected? It's much better to set process goals: ones that keep you accountable for doing the things that you know will pay off in the long run, despite any inevitable short-term setbacks. You've heard that lifting is a journey? That's a reflection of the fact that outcome goals don't work: if you meet them, you're only satisfied for a little while, before you set bigger and better goals; and if you miss, you're disappointed. Furthermore, process goals are entirely under your control. Athletes in particular are likely to pick outcome goals that involve factors outside of their own influence. For example, if you catch a cold, you'll Appendix 58 probably have a hard time hitting your target numbers for a workout. But you can still meet process goals, regardless of if you're feeling under the weather. keep you motivated in difficult situations: if you're sick or injured; fail to perform up to expectations; or life gets in the way of lifting entirely. Here are some examples of outcome goals: The first step requires that you have a clear vision for the future. This is not a goal! Think of it like the vision or mission for a company. Nike's mission, for example, is to bring "inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world." Harvard's vision is to create and sustain a college that will "enable all Harvard College students to experience an unparalleled educational journey that is intellectually, socially, and personally transformative." Your vision might be to become the greatest powerlifter of all time. Or it might be to look and feel like an athlete. Or maybe it's something totally different — it doesn't matter. The point of a vision is to keep you motivated on your journey, so if your vision does that, then it's a good one. • • • • Not getting injured in an entire training cycle Perfecting squat technique or squatting 500 pounds Gaining 10 pounds of muscle Going 9/9 at a meet And here are some examples of analogous process goals: • Warming up for 15 minutes before every training session • Committing to a new technique cue for at least four weeks • Consuming your target macros six days per week If you set the first outcome goal, you're in trouble if you happened to tweak your elbow playing a pickup game; and if squatting or building muscle don't come easily to you, the other two outcome goals might require a very long time to achieve. The process goals, on the other hand, are more manageable, realistic, and under your own control. Your vision doesn't even have to be achievable — in fact, if it's too precise, a vision just becomes a goal. "Becoming an IPF world champion," for example, isn't a vision. After all, if you do become a world champion, what's going to keep you motivated after that? Would you just retire? And, worse, what happens if you don't become a world champion? Does that mean your entire career was a failure? Even with process goals, it's important to have a clear understanding of why you're lifting — why you're on the journey in the first place. That's the only thing that can A vision isn't enough — you also need values to guide your decisions in striving towards that vision. Values are your personal beliefs about what's worthwhile in life. Appendix 59 Typically, the values we share with others are "good" things like honesty, justice, and perseverance. But the fact is, especially in America, a lot of people value winning over everything else. There's nothing wrong with that! They're your values, not someone else's, and not society's. Don't let other people shame you into letting their values take precedence over yours — that's a quick road to an unfulfilling life, and those people aren't worth your time in the first place. Only when you have a clear vision for your future, and you understand your personal guidelines (values) for achieving it, can you put yourself in the best position possible to accomplish that vision. More importantly, even if you fail, still have benefitted by adhering to your values, and can be confident that you did your best. What does all of this mean for attempt selection? Basically, if you’re really struggling with attempt selection, maybe you need a little distance between yourself and your outcome goals. Set process goals instead and base your meet prep cycle on a 5% improvement over your existing PRs. At the meet itself, set conservative openers and call your second and third attempts based on what you feel capable of that day. This isn’t the optimal approach if your goal is to win the meet, but it is oftentimes the best (and sometimes only) way to ensure that you perform your best. Appendix 60 TECHNIQUE Think Strong 61 Appendix 62 THE SQUAT For each of the major lifts, we’ll start with the setup. Many lifters overlook the setup, but it’s one of the most important parts of the squat — and the bench press and deadlift, too. Don’t start off at a disadvantage! EQUIPMENT Before you start squatting, make sure you’ve got the right equipment. You’ll need: • A non-slip shirt. It’s hard enough to hold the bar on your back without worrying about it rolling around. Get a thick, cotton shirt to squat in, and cover the shoulder and upper back area with chalk before you start sweating! • Wrist wraps. It’s always a good idea to support your wrists as much as possible when you’re placing a fairly heavy load onto them. Your shoulders should bear most of the weight in the squat, but there’s no reason to risk injury. • Knee wraps/sleeves. Either or both of these are great for helping to keep your knees safe and lifting more weight. • A belt. I’ve tried a lot of beltless squatting, and while it does strengthen the core, I’ve found that using a belt helps me keep better form and lift more weight. After you’ve got the right equipment, you’ll want to set a bar in a squat or power rack so that it’s at roughly midchest height. Make sure to have a spotter or some other safety system in place in case you’re not able to complete a rep for whatever reason. You’ll also want to find your ideal squat stance, before you even start lifting. It’s a good idea to start with your feet about shoulder width apart. Generally, a narrower stance will make it easier to hit depth (when your hip joint passes below the level of your knee joint) and place more emphasis on the quads and glutes than will a wider stance. You’ll have to experiment to find the width where you’re most comfortable, but if in doubt, just stick with shoulder width. POSITIONING THE BAR After you’ve braced, grab the bar and position yourself under the bar so that it’s across your shoulders and upper back. I prefer a low bar position, where the bar rests mostly on the rear delts; you might want a high bar position, where the bar rests mostly on your traps. You’ll have to experiment to find which works best for you, but generally, your bar position is okay as long as: 1. It’s below your cervical spine. Tilt your head forward and feel for the bump at the base of your neck, between your shoulder blades. The bar Appendix 63 needs to be below that, not on top of it. 2. It’s high enough up that you can hold it in place securely using your shoulders and back, not just your hands and wrists. Your grip placement is up to you, as well. Generally, a closer grip will provide more upper back tightness (good) but also more strain on the shoulders (bad). I like to start out with a wide grip and gradually bring it in each warmup set until I find that I cannot continue to bring it in without shoulder pain. UNRACKING THE BAR After you’ve braced and set under the bar, you need to unrack by squeezing your glutes. This will raise the bar enough to slide one foot back. Try not to pick your foot up off the floor, since that may cause you to lose balance with a heavy weight. You have two choices for the walkout: 1. You can take two steps back, sliding one foot and then the other into your squat stance. 2. You can take three steps back, sliding one foot back and towards the middle of your body, sliding the other foot straight back, and then adjusting the first foot to find your squat stance. The second method takes a bit longer, but may help you balance when unracking a heavy weight. Try both and see which you prefer, but do not take more than three steps — that’s just wasting energy. Finally, take one last deep breath to brace even tighter before beginning the descent. DESCENT Once you’ve set up properly, you need to lower your hips until they pass below the level of your knees. Many lifters think about the ascent as the hardest part of the squat, but actually, if you set up properly and make a good descent, lifting the bar takes care of itself (assuming you’re strong enough). Initiate the movement using your glutes and hamstrings. That requires you to keep tension in those muscles while, at the same time, driving your knees out and keeping your torso as vertical as possible. The easiest way to do all this is by using a cue, so think about “spreading the floor” with your feet. It’s okay for your knees to travel forward, but you need to keep your weight evenly distributed over your feet. If you’re way forward on your toes, you won’t be able to engage your glutes and hamstrings properly; and if that’s the case, you might benefit from wearing a heeled squat shoe. Appendix 64 Be patient on the descent, regardless of whether you squat quickly, using a lot of rebound. Patience will help you to stay calm and focus on your technique. help to power through your sticking point. OUT OF THE HOLE After you’ve hit depth, you need to reverse the bar’s motion without letting your hips rise faster than your shoulders. Remember, the bar is on your shoulders, so it’s your shoulders that need to come up. If your hips come up first, they haven’t helped lift the bar at all. Instead, initiate the ascent with your glutes. A great way to practice that is by sitting down on a high box or stool, without any weight, and standing back up just by squeezing your glutes, not by rocking or using your legs. Once you’ve got that down, you can gradually lower the height of the box or stool until you can stand up from a squat position using your glutes. It can also help to think about driving back, into the bar, or driving your elbows under the bar. Both of these cues will help to keep your torso upright as you ascent, which, in turn, will keep your hips underneath your shoulders. Ascend until your knees and hips are both locked. If you’re performing reps, you should inhale only between reps, not during them. Of course, it’s okay to exhale as you ascend, but not while you descend. Exhaling will cause you to lose tightness, but a forceful breath out can Appendix 65 Appendix 66 THE BENCH PRESS EQUIPMENT • A non-slip shirt. It’s even more important for the bench than for the squat. You don’t want to be sliding around with 400 pounds in your hands. • Wrist wraps. Again, much like with the squat, when you’re supporting a heavy weight using your wrists, it’s a good idea to protect them. Tight wraps can also help keep your wrists straight, which may prevent elbow pain. • A belt and knee sleeves. These are totally optional, but some people prefer the added tightness that a belt and knee sleeves provide, even on the bench press. Others find them unhelpful and restrictive. Try them and see whether they help, but don’t consider either a necessity. POSITIONING ON THE BENCH Once you’ve got your gear, set up in a good bench with a wide, non-slip surface and adjustable heights. You’ll want the bar at a height where, even without a spotter, you can just barely unrack it while keeping your elbows locked. Any lower, and you’ll have to do extra work to unrack the bar. You’ll need to find your proper grip width and foot position, too. Generally, a closer grip will place more emphasis on the triceps, and a wider grip on the chest. The widest you’re allowed to grip in competition is with index fingers on the outside rings of the bar. The narrowest grip I’d recommend is with index fingers at the end of the outside knurling. Start with a shoulder-width grip, and experiment with other placements to find what works best for you. You’ll also need to find your proper foot position. When viewed from the side, your feet should be directly underneath your hips. However, there’s no one right foot width: a narrower stance can provide more leg drive, but can also make it easy to accidently pick your butt up off the bench (which isn’t allowed in competition). Again, you’ll need to experiment to find what width works best for you. Finally, you need to set your arch. You’ve probably seen videos of fantastic benchers with unbelievable arches, and for some people, that works. But for most people, a huge arch isn’t realistic, either due to flexibility issues; or because a big arch means sacrificing other leverages in exchange for a shorter range of motion. A big arch can make it more difficult to get a powerful leg drive, too. I prefer a moderate arch in the lower back, and a very tight arch in the upper back and scapula. It’s very important that, throughout the entire movement, you keep your shoulder blades squeezed together tightly. This “lateral Appendix 67 arch” both protects the muscles of the shoulder joint and allows you to better incorporate your lats into the movement. Once you’ve set your grip, stance, and arch, take a deep breath, just like you were bracing for the squat or deadlift (you don’t need to contract your abs, though). Then lift the bar out of the rack by locking your elbows. I recommend having a spotter help you to unrack even moderately heavy weights, because the motion of moving the bar from over your head to over your chest can place a lot of strain on the shoulders. LOWERING THE BAR Just like in the squat, it’s important to lower the bar properly so that you’re in the best position possible to lift the bar properly. There are two general approaches to the descent: 1. You can lower the bar under control, keeping everything as tight as you possibly can. 2. You can “drop” the bar, still maintaining some control and tightness, but allowing gravity to do most of the work for you, and absorbing the weight’s momentum with your chest. first is the safer and usually stronger choice. Regardless of which option you choose, as you lower the bar, you probably want to keep your wrists straight, because a straight wrist will minimize elbow strain and, for most people, keeps the bar in a better position relative to the forearm and shoulder. You’ll also want to keep your pecs, lats, and arms tight throughout the entire descent; like with the squat, the easiest way to do all of this is by using a cue like “rip the bar apart.” You may have read or heard recommendations to keep your elbows tucked as tightly as possible throughout the entire movement. That’s not a bad idea, but generally, it’s more important to keep your shoulder blades tight than your elbows. Letting your elbows flare out helps incorporate your chest — a bigger muscle than your shoulders or triceps — so it’s not a bad thing. You’ll want to find the degree of elbow flare that maximizes your strength off the chest without putting strain on your shoulders. Again, that takes trial and error, but starting off with your elbows tucked is a fine idea. Finally, you should hold the weight at your chest for a brief period before pressing up. Touch-and-go reps (which omit this pause) are fine for some or even most of your training, but it’s important to practice pausing if you ever plan to compete. Neither option is right or wrong, but, for most people, the Appendix 68 OFF THE CHEST If the hardest part of the squat is getting out of the hole, the hardest part of the bench is getting the bar off your chest — while maintaining good position! It’s easy to heave the bar up a couple inches, but if you lose control of the bar path, it will be very difficult to save the lift. A strong, controlled press begins with the lats. If you kept your shoulder blades retracted and lats tight during the descent, you’ll be able to forcefully push up using your lats to begin the motion off the chest. You can practice this without weights: get in position on the bench as if you were about to press, and try to punch the ceiling. As you do, focus on the movement in your back — that’s (roughly) what you want to replicate when pressing off your chest. Obviously you’ll need to coordinate your lats with your traditional pressing muscles (pecs, shoulders, and triceps). As you press off your chest, try to keep your elbows angle steady — flaring out too early will bring the bar over your face and into a position where you lack the leverage necessary to finish the lift. Your goal when pressing off the chest is to generate enough momentum to carry the bar through your sticking point — the part of the lift where you’re weakest, and the bar begins to slow down. Generally, if you make it past the sticking point, you’ll make the lift. For most people, the sticking point in the bench is a few inches above the chest, so you want to press as forcefully as possible in order to get the bar above that point as quickly as possible. LOCKOUT Once you’re past the sticking point, you just need to stay patient to secure a good lift. It’s very possible that the bar will continue to slow, but if it does, don’t panic! You need to keep your position and the leverage it creates to complete the lift. First, if the bar starts to slow, try to push back, towards your head, to bring the bar directly over your eyes. This places your triceps in their strongest position to help finish the lift. At the same time, keep thinking about ripping the bar apart, or pushing out rather than up. Again, this will help use your triceps. Second, don’t forget about your chest. Even at lockout, your chest can help to move the bar up, so try to crunch or squeeze your pecs together to get as much as you can out of them. Finally, don’t flail. In a competition, moving your feet or lifting your butt up will get your lift turned down, but even in training, those habits don’t help to make the lift easier. Instead, continue driving your heels and hips back, in the direction you want the bar to go. Appendix 69 Appendix 70 THE DEADLIFT EQUIPMENT • Long socks. These help reduce the friction between your bar and the shins, protect you from scrapes, and keep you from bleeding all over the platform if you do bump your shins too much. • A belt. Just like with the squat, a belt is too much of an advantage to ignore on the deadlift. • Wrist wraps and knee sleeves. These are totally optional, but some people like wearing very tight wrist wraps to help their grip, and some like wearing knee sleeves for added protection. The deadlift can be deceiving. It looks like the simplest lift: just pick the bar up off the floor. But in truth, it’s a lot more difficult than that, and it starts with your setup. Just like in the squat and bench press, you can be successful with a wide variety of grips and stances in the deadlift. But unlike those first two lifts, the deadlift looks really different depending on whether you pull conventional (with feet inside of your arms) or sumo (with feet outside your arms). Generally, a conventional stance places more emphasis on your back and quads than does sumo, but sumo also tends to be less forgiving when it comes to technique errors. Choosing between a sumo and conventional stance is important, because depending on your leverages, it can make a huge difference. Fortunately, it’s pretty easy to tell if one stance feels more natural than the other, and regardless, good technique for both styles is nearly identical! For most people, the ideal conventional stance is somewhere around hip-width, and narrower than shoulder width. A sumo stance can be anywhere from shoulder width to the point where your feet nearly touch the inside plates on the bar; but start out with a stance that places your feet just outside your arms, to avoid straining your hips. It will take some trial and error to determine whether you’re better off sumo or conventional. Once you’ve found a good stance, you need to make a tight, controlled descent before you attempt to lift the bar. The “grip it and rip it” style isn’t ideal for most people, because it makes it harder to involve the lats and hamstrings in the lift. Instead, keep your lats, core, glutes, and hamstrings tight as you go to grab the bar — and when you do grab it, make sure that your arms hang straight down, not at an angle. OFF THE FLOOR The deadlift is all about controlled aggression. If you try to explode off the floor, you’re usually sacrificing tightness and technique. Instead, practice patience off the floor, Appendix 71 stay in a good position, and save the aggression for powering through your sticking point. To do that, you’ll want to use your legs and glutes to break the bar off the floor. Just like in the squat, “spread the floor” is a good cue to help activate your glutes and hamstrings, and “push the floor away” is another good one. Try both and see which feels more natural. Throughout the whole movement, you need to keep your core and back tight, by bracing your abs and pulling your lats down towards the bar. Pulling your lats down before you begin the lift will help you to keep a flat lower back throughout the lift and put your body in the ideal position to finish. It also might make the bar move more slowly off the floor. That’s okay — better a slow lift than no lift at all. LOCKOUT As soon as the bar leaves the floor, you need to accelerate. Your goal is to generate enough bar speed to help power through the sticking point — which, for most people, is somewhere between just below knee level and lockout. complete the lift. That doesn’t mean you need to lock your knees before your hips — many lifters find it easier to lock the knees and hips at the same time. However, thinking about locking your knees may help you move the bar faster once it leaves the floor. If you start to struggle towards the end of the lift, you need to stay calm and patient, not rush to complete the lockout. Rushing usually leads to hitching, and hitching always leads to missed reps. Instead, focus on keeping your core tight and squeezing your glutes to push your hips through and finish the movement. Forcefully exhaling can sometimes help to power through that last inch or two. LOWERING THE BAR After lockout, don’t drop the bar! In a competition, dropping the bar will cause you to miss lifts, and even in the gym, it’ll throw off your form and make your next rep more difficult than it should be. Instead, lower the bar under control by pushing your hips back and keeping your lats and core tight as the bar moves downward. To accelerate, continue focusing on either spreading or pushing through the floor. Your goal is to lock your knees as quickly as you can; as long as you kept a good position off the floor, if you can lock your knees, you’ll be able to use your upper back to help bring your hips through and Appendix 72 Appendix 73 CORE/AB TRAINING overhead pulley crunch or crunch on a Swiss ball are both great ways to practice this feeling of tightness. Squats and deadlifts begin with your core — your abs and lower back. These major muscle groups stabilize your torso during the lifts, keeping it in a strong and safe position. The ideal core position balances the load between your back, hips, legs, and glutes. Once you’ve fully engaged your abs, you need to generate intra-abdominal pressure. While holding the crunch position, exhale forcefully, trying to blow all the air out of your lungs. Then — keeping your abs tight the whole time — inhale deep into your diaphragm and “push out” against that tightness, like you were drawing in a huge breath to blow up the world’s biggest balloon. When done properly, you should feel like you have a wall of muscle supporting your entire core, from your hips to your rib cage. To find this ideal position, you need to “brace” your abs and lower back. Many trainers use a cue like “push out” to convey the idea of intra-abdominal tightness, but that’s not nearly enough. First, you need to properly engage your upper and lower abs. I like to start with the lower abs, and I think about using them to rotate or pull my hips towards my shoulders. Some other good cues include “scooping” your abs, or “drawing in,” trying to pull your navel towards your spine. If you have trouble with this and cues aren’t helping, try lying down flat on the floor and crunching your abs together, as if you were trying to squeeze a penny in your belly button. Then push your lower back into the floor as hard as you can. Try to replicate that feeling of tightness while standing up. The first time you do it, this whole process will seem exhausting. You’ll need to practice. Fortunately, this is the position you should keep for ALL of your abs exercises, whether they’re planks, sit-ups, leg raises, or anything else, so you should have plenty of opportunities! Every time you train abs, try to practice holding this position. It will strengthen quickly, and you’ll see big gains in your squat and deadlift just from training this position. Second, you need to engage your upper abs in the same way. I use almost the same cue here, thinking about using my upper abs to crunch down and rotate my shoulders towards my hips. If that doesn’t work for you, trying thinking about “bearing down” with your rib cage. The Appendix 74 BENT-OVER ROW 1. Begin by loading a barbell on the floor as if you were preparing to deadlift. 2. Hinge at the hips, keeping your core braced, back flat, and butt high. Your knees should be soft but not bent. Direct your gaze a few feet in front of the barbell. 3. Initiate the movement using your rear delts and lats, not your arms or traps. If you’re having trouble, try focusing on driving your elbows backward, as if you were trying to elbow someone behind you in the gut. 4. Squeeze your shoulder blades together at the top of the movement, and try to hold that position for a full second. 5. Lower the barbell all the way to the floor under control, and let it rest briefly on the floor before performing the next rep. REVERSE HYPEREXTENSION 1. Load the machine with a very light weight (20 pounds is a good place to start). 2. Position yourself in the usual way, with your chest as close to the pad as possible, hip crease against the edge of the pad, and strap behind ankles. Keep your toes and heels together throughout the entire movement. 3. Begin the lift by contracting your glutes, while keeping your abs tight. Try to bring your feet up to the level of your torso. 4. At the top of the movement, squeeze your glutes and hold for a one-second count. 5. Lower the weight under control. 6. Repeat for the required reps. Appendix 75 CHIN/PULL UP 1. Begin with a safe setup. You should have a stable chinning bar (no over-the-door BS), and an easy way to take your grip (no 18-inch jumps to grab the bar). Use a block or chair to get up if you have to. 2. Set your hands about shoulder-width apart, with palms facing you (supinated). If you prefer to have your palms facing away, that’s fine, too. 3. After you grab the bar, depress your scapula (pull your shoulders down). This will take some of the strain off your rotator cuff muscles. 4. Squeeze yourself up towards the bar by pulling with your lats. This is tricky, especially if you don’t have a lot of lat development yet. Some cues that might help: • “Elbows down” • “Pull the bar apart” • “Don’t pull with your hands” 5. All of these will help to avoid using your biceps too much (although you will have some bicep involvement). getting stronger if you do more reps at the cost of range of motion. 7. Don’t use momentum. Some people have good reasons for performing kipping pull-ups, but if you’re a powerlifter, you do not. The easiest way to avoid swinging too much is by bracing your core and flexing your glutes as you perform the movement. GLUTE-HAM RAISE 1. Position yourself on the GHR with your whole foot pressed against the back plate, your ankles directly between the foot pads, and your knees aligned with the bottom of the large front pad. Your knees should be bent at about a 45-degree angle. 2. Brace your core and glutes, and extend your knees by driving your toes against the back plate until your body is parallel to the floor. 3. Return to the starting position by driving your heels back towards the back plate, squeezing your hamstrings and glutes and keeping your core tight. 4. Repeat for the desired number of reps. 6. Continue pulling until either (A) your chin is over the bar or (B) your chest touches the bar. Either is okay, but make sure you’re consistent. You’re not really Appendix 76 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Part of learning to Think Strong is learning to acknowledge the people who help you get strong. I cannot thank these people enough for all of their support, but I hope I can give back to them a little of how much they have given to me. 77 Staci Ardison has contributed to this project, and to my life, in ways that I can’t fully describe. I’m so grateful to her for her trust in and support of me. She has challenged me to reexamine the way I think about everything — training included — and I would not have learned to Think Strong or be strong without her. Dominic Morais and Jacob Cloud are by far the two most influential people in my training, and two of the most influential people in my life. I can’t overstate all they’ve done for me with their patience and friendship, and I can’t describe how supporting it is to know that I can rely on them for advice — good advice — about anything. And their perspective on training and technique alone has added more to my total than anything else; they deserve as much credit for my lifting success as I do. Tammy Hudson has done so much to keep my going, and I have never met another sport massage therapist with as much knowledge of the body and how to fix it. Her support and friendship have been just as important to me, and I’m grateful to have met her. All of my family at Big Tex Gym and Hyde Park Gym in Austin have pushed me to continually improve, and I am extremely grateful for that. Everyone talks about how important it is to have a “hardcore” gym environment for motivation, but fewer recognize how much of a difference it makes when you train with family. Intense training partners can push you to work harder when you’re not feeling it, but a family can keep you going through the good times and the hard ones. I’m also grateful to my parents for everything they’ve given to me. I know that it took them a while to come around to powerlifting, and I appreciate that they were open-minded enough to support me just because lifting is important to me, even when they maybe didn’t understand why. And finally, I’m so proud to be a member of Team EliteFTS. I’m thankful to Dave Tate for giving me this opportunity, to Sheena Leedham and Andy Hingsbergen for their help in navigating the team processes, and to the entire team for all of their support and friendship. To live, learn, and pass on really encompasses everything that I want to get out of this sport, and really out of my entire life, and so it’s incredibly fulfilling to be a part of something bigger than myself, where everyone can share that vision. Acknowledgements 78 WANT MORE? 79 If you’re made it this far, and still think you could use a little more guidance, I offer online programming for both training and nutrition. I’ve worked with powerlifters, bodybuilders, fire and safety officials, and general training enthusiasts of all levels. If you’re interested in training with me, please contact me via email at ben@phdeadlift.com. Here are a few testimonials from some of my clients: “I would have to say [my meet] ended up being successful... just a special day that I’ll always remember. Definitely couldn’t have done any of this without your guidance and help throughout this whole process.” “Thank you so much for your help. You have significantly helped me progress in my lifting journey... I’ll take your words to heart and I hope to share the platform with you in the future.” “[Training is] a bombastic bomb... my body and especially my strength is responding well!” “Literally the perfect weights. I don’t know how you picked them but they were just right... I’ll do your programs forever.” Services 80