Negative Social Interactions, Gender, Race, Immigration in Canada

advertisement

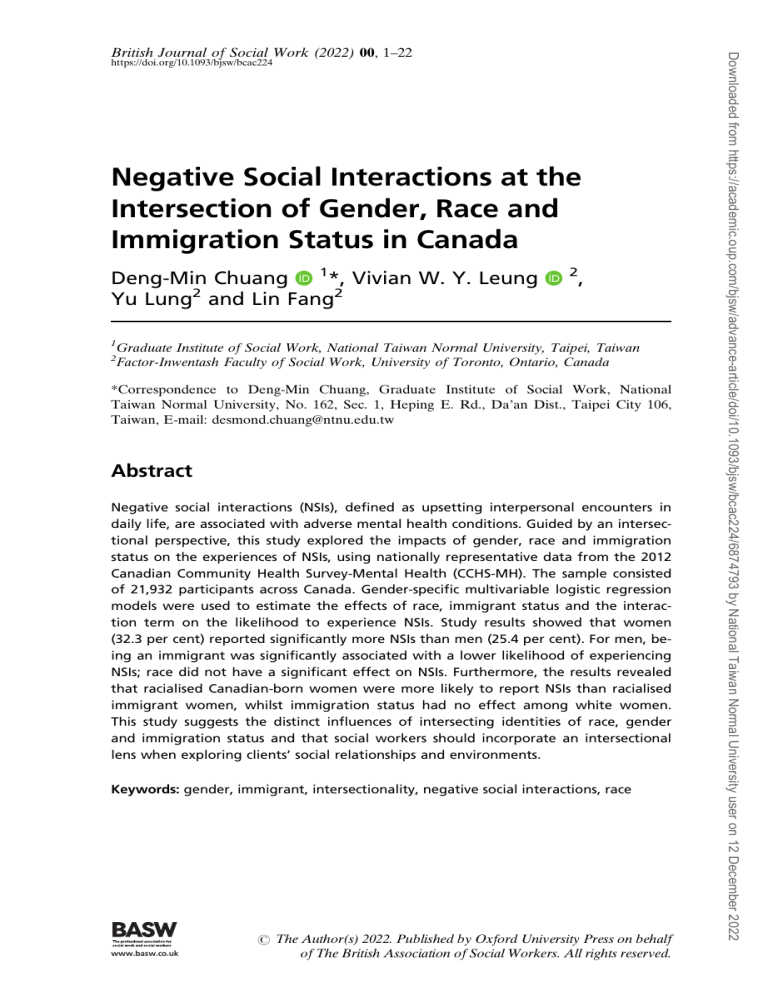

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224 Negative Social Interactions at the Intersection of Gender, Race and Immigration Status in Canada Deng-Min Chuang 1*, Vivian W. Y. Leung Yu Lung2 and Lin Fang2 1 2 2 , Graduate Institute of Social Work, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada *Correspondence to Deng-Min Chuang, Graduate Institute of Social Work, National Taiwan Normal University, No. 162, Sec. 1, Heping E. Rd., Da’an Dist., Taipei City 106, Taiwan, E-mail: desmond.chuang@ntnu.edu.tw Abstract Negative social interactions (NSIs), defined as upsetting interpersonal encounters in daily life, are associated with adverse mental health conditions. Guided by an intersectional perspective, this study explored the impacts of gender, race and immigration status on the experiences of NSIs, using nationally representative data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health (CCHS-MH). The sample consisted of 21,932 participants across Canada. Gender-specific multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the effects of race, immigrant status and the interaction term on the likelihood to experience NSIs. Study results showed that women (32.3 per cent) reported significantly more NSIs than men (25.4 per cent). For men, being an immigrant was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of experiencing NSIs; race did not have a significant effect on NSIs. Furthermore, the results revealed that racialised Canadian-born women were more likely to report NSIs than racialised immigrant women, whilst immigration status had no effect among white women. This study suggests the distinct influences of intersecting identities of race, gender and immigration status and that social workers should incorporate an intersectional lens when exploring clients’ social relationships and environments. Keywords: gender, immigrant, intersectionality, negative social interactions, race www.basw.co.uk # The Author(s) 2022. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of The British Association of Social Workers. All rights reserved. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 British Journal of Social Work (2022) 00, 1–22 Accepted: November 2022 Introduction Interpersonal encounters can render support but can also be plagued with arguments and tension. Negative social interactions (NSIs) are upsetting interpersonal encounters that occur in different settings in daily life, such as the household, the workplace, school and the neighbourhood. Scholars have defined such interactions as ‘exchanges or behaviours that involve excessive demand, criticism, disappointment or other unpleasantness’ (Sneed and Cohen, 2014, p. 554). NSIs tend to happen with those whom we interact with more frequently (Williams and Fredrick, 2015; Offer and Fischer, 2018), and their effects may remain for a long time if personal networks are unchanged (Wilson et al., 2015). Scholars have reported that NSIs are less prevalent than positive social support, with about 13–16 percent of the social interactions considered negative in the USA (Offer and Fischer, 2018) and rural Honduras (Isakov et al., 2019), reflecting individuals’ strong preference for engaging in balanced relationships. However, a recent study has found that Canadians may bear a high level of NSIs, with participants rating 30 per cent of the interactions experienced within the last month as negative (Gulliver and Fowler, 2022). One explanation could be that a high level of NSIs may be associated with a lack of social integration (Gulliver and Fowler, 2022) and having lower levels of a sense of belonging (Kitchen et al., 2015) among Canadians. Previous literature has documented the detrimental effects of NSIs on individuals’ mental health, such as depression (Eidelman et al., 2019), psychological distress (Offer, 2020) and substance use (Croezen et al., 2012). Other studies have also indicated that individuals who had experienced NSIs were more likely to report traumatic events in their lives than individuals who had never experienced NSIs (Lincoln et al., 2005). Additionally, previous evidence suggests that NSIs have a stronger effect than social support on individuals’ psychological well-being, not only because NSIs are usually unexpected but also because the stress that NSIs cause may require avoidant coping strategies to resolve (Offer, 2020, 2021). Although researchers have paid attention to the negative aspects of interpersonal interactions, few studies have addressed the fact that the experience of NSIs may vary according to individuals’ intersecting identities, such as gender, race and immigration status. Given the insufficient attention paid to the interplay of gender, race and immigration status and their effect on the quality of social interactions, the current study proposes a framework based on intersectionality and examines the relationship between the intersection of gender, race and immigration status and NSIs in a multicultural society, such as Canada. In this context, we Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 2 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. aspire to contribute to the field of social work to better understand the impact of intersecting identities on the quality of social interactions. NSIs and gender The literature related to NSIs and gender is inconsistent. Some previous research has suggested that gender-specific stressors and expectations play a role in the NSIs the individuals encounter. For example, men are often expected to act as providers for their households and have limited responsibilities in terms of care work, whilst women, on the other hand, are expected to share the responsibilities of income generation along with performing other family care duties (Noh et al., 2017; Sherman, 2017). If these expectations of socially constructed roles are not met, daily interactions can be stressful for both genders, although they may be experienced differently by men and women. For instance, men were more likely to report high levels of NSIs from their interactions with family members if they did not play the role of provider for the household (Nguyen, 2017). Women, however, were more likely to be exposed to intimate partner violence if they did not meet gender expectations (Guruge et al., 2015). Thus, a previous study in the USA has indicated that societal and cultural regulations may constrain people to stay with those who they feel discomfort and stress with (Offer and Fischer, 2018). Other studies have found that gender differences in NSIs were associated with different levels of social support (Turner and Lloyd, 2004). For example, women may have higher levels of social support from their friends and family, which act as a buffer against the influence of NSIs (Fiori et al., 2013). The same results have been found in other Canadian studies (Rezazadeh and Hoover, 2018; Morgenshtern, 2019). Other studies, however, have indicated that NSIs are not associated with gender among older adults with financial needs (Krause et al., 2008) and cognitive impairment (Wilson et al., 2015). These inconsistencies indicate that other life circumstances, such as financial adversities and cognitive dysfunction, may be of more salient factors when combined with the effects of gender. Therefore, it could be argued that other identities might be intersecting with gender and generating a salient effect on NSIs, apart from the effect of gender alone. Since previous studies have overlooked the intersection of gender and other identities on NSIs, the present study aims to explore this effect through an intersectional lens. NSIs and race As mentioned above, an understanding of NSIs only in terms of genderbased distinctions may inadequately represent the impact of multiple Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 3 of 22 identities. Race can also be relevant, as reflected in differences between the social experiences of white individuals and racialised individuals, given that white individuals are typically understood as the dominant racial group in North America, including Canada. For example, racialised Americans were more likely than white Americans to experience NSIs in their personal networks because the societal systems surrounding race generate differing opportunities, constraints and demands that affect the quality of social relationships for racialised individuals (Lindsay, 2015; Nguyen, 2017; Kallman, 2019; Offer, 2020). Notably, findings of racial differences in social interactions are inconsistent. For instance, previous research has found that, compared to white individuals, racialised individuals were more likely to develop high-quality social interactions with their children and with adults in their social networks (Kim and McKenry, 1998). It may be that the oppression faced by racialised individuals in their daily lives has had the effect that they have built up closer relationships within their ethnic social networks. Other studies, however, have found that racialised individuals experienced lowerquality social interactions, such as greater exposure to childhood adversity and higher levels of interpersonal stress in their adulthood (Lincoln et al., 2003; Umberson et al., 2014). Research conducted in Canada has suggested that racialised Canadians had lower-quality social interactions than white Canadians due to perceived racial discrimination and hate crimes (Veenstra et al., 2020). Overall, the inconsistent findings of the relationship between race and NSI suggest that there remain many areas in which racial differences in social interactions can be further investigated. Other socio-economic positions could also intersect with race in the experience of various types of social interactions. NSIs and immigration status Immigrants, especially members of visible and racial minorities, experience differentiated treatment or types of interaction due to their immigration status (Harell et al., 2017). Previous studies have documented that the perception of being treated unfairly by others due to immigration status could have tremendous effects on immigrants’ mental health, such as depressive symptoms (Xu and Chi, 2013). A recent study has also found that negative experiences of social interaction due to immigration status had a significant impact on immigrants’ interpersonal relationships, such as decreasing trusting relationships with others (Pellegrini et al., 2021). Furthermore, a study (Nakash et al., 2021) involving sixteen European countries (e.g. Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, French and Germany) examined the association between quality of social network and quality of life and whether the association varies between immigrants and native-born individuals. The results showed that Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 4 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. immigrants felt more emotionally close to their social network when they had a high perceived quality of life, but that this association was not shown among native-born individuals. Other research has also found that immigrants may experience fewer NSIs because immigrants are more likely to have higher education and more social capital, which are protective factors against NSIs (Evans and Erickson, 2019). Other studies in Canada have also indicated that the quality of an individual’s social interactions somehow represents an individual’s social positions (e.g. Rezazadeh and Hoover, 2018; Veenstra et al., 2020). Yet, our review of the literature suggests that there is still limited evidence for drawing an association between immigration status and NSIs. It is unclear if the effects of immigration status vary across other social identities, such as gender and race, in Canada. Intersectionality as a theoretical framework Using intersectionality as a theoretical framework, we examined how the interaction of gender, race and immigration status impacted the experiences of NSIs. The intersectional framework alerts us that examining a single social identity may provide insufficient information for addressing the complicated social structures and contexts an individual may face in society (Crenshaw, 1989; Collins, 2000). Moreover, socially defined identities interact with one another and reshape a collective social meaning linked to either privileged or marginalised status within society (Gonçalves and Matos, 2020). In the North American societal systems, individuals with different racial backgrounds may encounter different opportunities, expectations and demands that affect their daily social interactions. Moreover, when gender and race intersect with each other, the accompanying racial privilege, sexism and other internalised structural barriers may be determinative of individuals’ personal networks and social interactions (Lindsay, 2015). Additionally, people of different races and cultures may bear different gender role expectations from those in their personal networks (van de Vijver, 2007). As gender role expectations are believed to be among the reasons for gender differences in NSIs (Noh et al., 2017; Sherman, 2017), the intersection of race/culture and gender could be important to the experiences of NSIs. Several studies have illuminated how the intersection of gender and racial identities impacts individuals’ self-concept (Buckley, 2018), psychological well-being (Rogers et al., 2015), cultural stereotypes (Ghavami and Peplau, 2013), health inequalities (Veenstra et al., 2020) and experiences of harassment (Buchanan et al., 2018). As suggested by the previous review, the intersection of gender and racial identities could have an impact on the quality of social interactions. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 5 of 22 Although to our knowledge there is no existing literature about the effect of the intersection of gender, race and immigration status on NSIs, some previous studies have shed light on the potential to examine these three social identities within an intersectional framework. For instance, one recent study found that, compared to white Canadian-born women, Asian women born in China and white women born in Italy were more likely to report poor physical and mental health conditions in Canada due to the lack of culturally safe care and support (Veenstra et al., 2020). Other studies have indicated that the intersectional identities of gender, race and immigration status are associated with health inequalities (Patterson and Veenstra, 2016), labour market discrimination (Ngoubene-Atioky et al., 2020) and risk of depression (Evans and Erickson, 2019). Taken together, these three social identities—gender, race and immigration status—may result in different experiences of social interactions. Hence, using intersectionality as a framework, the current study aims to further understand the association between NSIs and intersecting social positions, namely gender, race and immigration status in Canada. The Canadian context In 1871, the first Canadian census documented that 60.5 per cent of the Canadian population reported ethnic origins from the British Isles, 31.1 per cent reported French origins and less than 1 per cent reported Aboriginal origins (Statistics Canada, 2017). After several changes in immigration policy, the current Canadian population comprises 36.99 million individuals, with 18.76 million women living in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2021). Although the British Isles (32.5 percent) and France (13.6 percent) are still among the most commonly reported ethnic origins and close to 20 million people reported European origins, 22.3 per cent of the Canadian population were members of visible minorities, with most of these individuals identified as South Asian, Chinese or Black, suggesting a growing trend towards a more diverse society (Statistics Canada, 2017). According to the 2016 Census in Canada, more than one out of five people were first-generation immigrants to Canada, 21.9 per cent of the population reported that they were or had ever been a landed immigrant or permanent resident in Canada. The immigrant population was estimated to reach around 30 per cent by 2036 (Statistics Canada, 2017). The majority (60.3 percent) of the first-generation immigrants were admitted under the economic category, which means that they were selected for their ability to contribute to Canada’s economic system, such as by making a substantial investment, meeting labour market needs or managing a business; 26.8 per cent were admitted under the family reunification category to join family already in Canada and around 12.9 per cent were admitted to Canada as refugees. This breakdown shows the Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 6 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. overall picture of immigrants’ social capital and networks after landing in Canada. Since the population landscape of Canada has become more diverse, more studies are needed to explore the nature of social interactions between individuals sharing diverse ethnic and immigration backgrounds. Within an intersectional framework, we attempt to inquire whether the quality of social interactions varies according to individuals’ intersecting social identities related to gender, race and immigration status. In this context, we aspire to add to the body of knowledge in the field of social work. The present study Although substantial differences in the experience of NSIs have been found among various identities, most past studies have examined specific community populations or have mostly used qualitative methods to approach the topic of intersectionality and social interactions in Canada. There have been few studies using population-based data-sets to examine the effect of NSIs through an intersectional lens. Using population-based data and a gender-specific analysis, the present study aims to examine the association between the intersection of race and immigration status and the experience of NSIs, and whether the association varies between men and women in Canada. The present study tests four hypotheses: (i) racialised individuals experience higher levels of NSIs than white individuals; (ii) immigrants experience fewer NSIs than Canadian-born individuals; (iii) the effect of race on NSIs varies across immigration statuses; and (iv) the above effects vary across genders. Method Data and study sample Data were drawn from the 2012 Canadian Community Health SurveyMental Health (the 2012 CCHS-MH), a nationally representative crosssectional survey that comprised 25,113 participants over fifteen years of age living in ten Canadian provinces (Statistics Canada, 2013a). CCHS-MH used a three-stage design. In the first stage, the geographical areas were selected based on the probability proportional to size method, followed by systematic sampling in the dwelling sample in the second stage. Once a dwelling was selected, a household member was randomly selected for the CCHS survey. The survey excluded residents of reserves and other aboriginal settlements in the provinces, full-time members of the Canadian Forces and people who were institutionalised. Statistics Canada conducted the CCHS-MH data collection from January to December 2012, using computer-assisted personal Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 7 of 22 interviewing completed by trained interviewers. The majority of the interviews (87 percent) were completed in person (Statistics Canada, 2013b). Previous peer-reviewed papers have used the 2012 CCHS-MH for further analyses and publications on mental health care (Sunderland and Findlay, 2013), substance use (Urbanoski et al., 2017) and employment insecurity (Kim et al., 2021). In total, 21,932 participants who had complete data for all variables were included in the analyses. As 2012 CCHS-MH data-sets are publicly accessible and the data do not contain personally identifiable information, the study is exempted from the university’s ethics review. Measures Outcome variable In the 2012 CCHS-MH data-sets, NIS was measured by one module, with one dichotomous variable addressing a general assessment of NSIs, as well as four-item questions assessing detailed experiences of NSIs, including excessive demands made by others, criticism by others, the thoughtlessness of others and the experience of others’ anger (Krause, 2005). For the current study, we wanted to examine the association between the intersection of gender, race and immigration status and the general experience of NSIs; therefore, the single, dichotomous item of NSIs was included as the outcome variable. During the data collection, interviewers first introduced the concept of NSIs by simply mentioning that ‘The contact we have with others is not always pleasant. The next questions are about negative interaction with others’, and then asked participants the following question, ‘Are there persons with whom you are in regular contact that are detrimental to your wellbeing because they are a source of discomfort and stress?’ Answers were coded as 0 ¼ No and 1 ¼ Yes. Social identity variables The three social identity variables are: gender (0 ¼ men; 1 ¼ women), race (0 ¼ white; 1 ¼ non-white) and immigration status (0 ¼ Canadianborn; 1 ¼ foreign-born). Socio-economic characteristics Socio-economic characteristics include age (0 ¼ 15–19, 1 ¼ 20–29, 2 ¼ 30– 39, 3 ¼ 40–49, 4 ¼ 50–59, 5 ¼ 60–69, 6 ¼ 70þ years), marital status (0 ¼ single, 1 ¼ married or in a common-law relationship, 2 ¼ formerly married), education (0 ¼ less than a post-secondary degree, 1 ¼ post-secondary degree and above) and personal income (0 ¼ Canadian dollar Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 8 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. (CAD) 10,000 or less, 1 ¼ 10,000–19,999, 2 ¼ 20,000–29,999, 3 ¼ 30,000– 39,999, 4 ¼ 40,000–49,999, 5 ¼ 50,000 or more). Mental health conditions Mental health conditions were assessed using two items: substance use (‘whether participants had used illicit drugs or medicine in a non-medical way in the past 12 months, including one-time cannabis use’) and mood disorder (‘Do you have a mood disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia?’) (0 ¼ no; 1 ¼ yes). Data analysis All analyses were performed using SPSS version 27. Descriptive statistics were used to report the frequencies and proportions of all variables. Chisquare tests were conducted to examine the distributions of socioeconomic characteristics, mental health conditions and NSIs based on gender, race and immigration status. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations between intersectional social positions and NSIs. We created gender-specific models to evaluate the contribution of intersecting identities to NSIs, that is the analyses were run separately for men and women. Adjusted population weight, calculated by dividing each master weight by the average weight, was used in all the analyses to obtain a sample equal to the population’s distribution in Canada. To assess the effects of social identities on NSIs, we adjusted first socio-economic characteristics and mental health conditions, and then race and immigration status in the second step. To assess the interaction effect between race and immigration status, we included an interaction term of race immigration status in the final step. All tests were considered significant at p < 0.05. Results Descriptive of the study sample The study sample consists of a total of 21,932 individuals, with 10,322 (51.8 wt%) men and 11,610 (48.2 wt%) women. Weighted estimates suggest that, compared to men, women were older, more educated, had lower incomes and were more likely to have been formerly married. Women also showed higher levels of mood disorders. No significant difference in race and immigration status was found between men and women. Compared to white participants, non-white participants were younger, more educated, more likely to be foreign-born, more likely to be single and had lower Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 9 of 22 incomes and lower levels of substance use and mood disorder. Compared to Canadian-born participants, immigrants were younger, more educated, more likely to be non-white, more likely to be married or in a common-law relationship and had higher incomes and lower levels of mood disorder. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for key variables. Bivariate analysis Women were more likely to report of experiencing NSIs than men (32.3 per cent versus 25.4 per cent, p < 0.001); white participants were more likely to report of experiencing NSIs than non-white participants (29.4 per cent versus 26.4 per cent, p < 0.001) and Canadian-born participants were more likely to report of experiencing NSIs than immigrants (30.3 per cent versus 24.0 per cent, p < 0.001). Table 2 presents the bivariate analysis. The percentage of participants reporting NSIs was significantly different across race and immigration status in both men (v2 ¼ 59.71, p < 0.001) and women groups (v2 ¼ 62.57, p < 0.001). Among men, the highest percentage of participants reporting NSIs occurred among racialised Canadian-born men (27.2 per cent), followed by white Canadian-born men (27.1 per cent). Among women, the highest percentage of participants reporting NSIs occurred among racialised Canadianborn women (39.5 per cent), followed by white immigrant women (33.3 per cent) and white Canadian-born women (33.2 per cent). Multivariable logistic regression Table 3 presents a gender-specific multivariable analysis between intersecting social identities and NSIs, adjusting for socio-economic characteristics and mental health conditions. For men, immigration status was a significant factor in experiencing NSIs, but race was not a significant predictor. Immigrant men reported 35 per cent lower odds of experiencing NSIs (AOR ¼ 0.65, 95% CI 0.55–0.76, p < 0.001) than Canadian-born men. The interaction term race immigration status was not significant for men (AOR ¼ 1.16, 95% CI 0.90–1.49, p ¼ 0.258), meaning that the effect of immigration status on NSIs was not dependent on race. Among women, race, rather than immigration status, was a significant factor in experiencing NSIs. Compared to white women, racialised women had 22 per cent increased odds of experiencing NSIs (AOR ¼ 1.22, 95% CI 1.04–1.44, p ¼ 0.018). The interaction term was significant in the model for women (AOR ¼ 0.48, 95% CI 0.38–0.61, p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 1, whilst immigrant status had no effect on white women’s likelihood of experiencing NSIs, racialised Canadian-born women had a higher chance of experiencing NSIs than racialised immigrant women. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 10 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. Gender Man Woman Race white Non-white Immigrant status Canadian-born Foreign-born Age group 15-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70 and above Marital status Single Married/common law Formerly married Education Less than post-secondary Post-secondary Personal Income Less than $10,000 Characteristics — — 77.3 22.7 75.1 24.9 8.5 17.2 15.1 17.0 19.3 12.9 10.1 30.0 62.0 8.0 40.9 59.1 3.5 18,361 (77.4) 3,571 (22.6) 18,241 (75.1) 3,691 (24.9) 1,559 (7.3) 3,158 (15.8) 3,191 (15.9) 2,990 (17.7) 3,717 (18.9) 3,600 (13.1) 3,717 (11.2) 6,268 (26.3) 11,026 (60.7) 4,638 (13.1) 9,545 (40.0) 12,387 (60.0) 1,838 (8.1) Man, % 10,322 (51.8) 11,610 (48.2) N (%) Total 13.2 60.8 39.2 22.3 59.2 18.5 6.1 14.4 16.8 18.6 18.5 13.3 12.3 75.1 24.9 77.4 22.6 — — Woman, % Gender <0.001 0.011 <0.001 <0.001 0.966 0.848 p-value 8.0 59.4 40.6 24.3 61.7 14.0 6.4 14.5 14.0 16.9 20.4 14.9 12.9 87.7 12.3 — — 51.8 48.2 White, % 8.7 61.8 38.2 33.1 57.0 9.9 10.4 20.3 22.4 20.5 14.0 6.9 5.4 32.0 68.0 — — 52.0 48.0 Non-white, % Race 0.031 0 .003 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.848 p-value 8.3 57.7 42.3 28.7 58.1 13.2 8.5 16.5 15.1 16.6 19.3 13.2 10.7 — — 90.4 9.6 51.9 48.1 No, % 7.5 66.8 33.2 18.9 68.3 12.8 3.6 13.8 18.5 21.2 17.9 12.6 12.5 — — 38.3 61.7 51.8 48.2 Yes, % Immigrant status Table 1. Description of socio-demographics, NISs and other psychosocial factors: unweighted frequencies and weighted percentages (N ¼ 21,932) (continued) 0.002 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.966 p-value Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 11 of 22 N (%) Total $10,000–$19,999 3,330 (14.1) $20,000–$29,999 5,538 (23.7) $30,000–$39,999 2,837 (13.7) $40,000–$49,999 2,228 (10.8) 50,000 or more 6,161 (29.6) Substance use, the last year No 18,210 (82.9) Yes 3,722 (17.1) Any mood disorder (lifetime) No 20,153 (92.9) Yes 1,779 (7.1) NISs No 15,724 (71.3) Yes 6,208 (28.37) Characteristics Table 1. (continued) 19.6 28.4 12.0 9.9 16.9 82.7 17.3 90.9 9.1 67.7 32.3 83.1 16.9 94.8 5.2 74.6 25.4 Woman, % 8.9 19.4 15.2 11.6 41.4 Man, % Gender <0.001 <0.001 0.373 p-value 70.6 29.4 92.3 7.7 82.5 17.5 14.0 23.5 14.1 10.8 29.7 White, % 73.6 26.4 95.1 4.9 84.3 15.7 14.2 24.5 12.3 10.9 29.7 Non-white, % Race <0.001 <0.001 0.002 p-value 69.7 30.3 91.8 8.2 82.8 17.2 14.5 23.3 13.9 10.6 29.4 No, % 76.0 24.0 96.2 3.8 83.2 16.8 12.9 24.9 13.1 11.3 30.3 Yes, % Immigrant status <0.001 <0.001 0.464 p-value Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 12 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. Table 2 Intersection and bivariate analyses of gender, immigrant status and race: Unweighted frequencies and weighted percentage (N ¼ 21,932) Variables Gender Man Woman NISs Man No Yes Woman No Yes Canadian-born Immigrants White N (%) Non-white N (%) White N (%) Non-white N (%) 7,671 (87.2) 7206 (88.1) 865 (12.8) 721 (11.9) 1,122 (33.6) 974 (30.3) 1,711 (66.4) 1,661 (69.7) p-value <0.001 <0.001 5,732 (72.9) 2,055 (27.1) 546 (72.8) 200 (27.2) 651 (82.4) 145 (17.6) 789 (78.0) 204 (22.0) 6,034 (66.8) 2,841 (33.2) 527 (60.5) 306 (39.5) 673 (66.7) 230 (33.3) 772 (75.2) 227 (24.8) <0.001 Table 3. Associations of intersectional social position groups and NISs by gender (N ¼ 21,932). Variable characteristics Age group (versus 15–19) 20–29 30–39 40–49 50–59 60–69 70 and above Marital status (versus formally married) Single Married/common law Educational level (versus post-secondary) Less than post-secondary Personal income (versus less than 10,000) 10,000–19,999 20,000–29,999 30,000–39,999 40,000–49,999 50,000 and above Past-year substance use (versus no) Has a mood disorder (versus no) Intersectional social positions Race Immigration status Race immigration status Man (N ¼ 10,322) Woman (N ¼ 11,610) AOR 95% CI p-value AOR 95% CI p-value 1.29 1.51 1.61 1.31 0.86 0.50 1.06–1.57 1.22–1.88 1.30–2.01 1.05–1.63 0.68–1.10 0.38–0.65 0.010 <0.001 <0.001 0.016 0.226 <0.001 0.91 1.01 1.37 1.11 0.72 0.28 0.73–1.13 0.79–1.28 1.08–1.73 0.88–1.41 0.56–0.92 0.21–0.37 0.380 0.958 0.010 0.385 0.009 <0.001 1.03 1.49 0.91–1.17 1.23–1.80 0.618 <0.001 0.98 1.38 0.86–1.12 1.17–1.63 0.783 <0.001 1.05 0.95–1.16 0.353 1.13 1.03–1.24 0.014 1.28 1.10 1.08 1.15 1.33 0.92 2.32 1.28–0.96 1.10–0.84 1.08–0.83 1.15–0.87 1.33–1.03 0.82–1.03 1.95–2.75 0.091 0.496 0.564 0.333 0.030 0.147 <0.001 1.01 1.00 1.21 0.99 1.04 1.35 1.79 0.86–1.17 0.87–1.17 1.02–1.44 0.83–1.20 0.88–1.22 1.21–1.50 1.56–2.06 0.931 0.956 0.029 0.947 0.665 <0.001 <0.001 0.97 0.65 1.16 0.82–1.14 0.55–0.76 0.90–1.49 0.679 <0 .001 0.258 1.22 1.08 0.48 1.04–1.44 0.93–1.25 0.38–0.61 0.018 0.342 <0.001 Discussion The present study has contributed to the current knowledge of NSIs by exploring the intersection of the three social identities. Our results showed a significant main effect of gender: men were less likely than Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 13 of 22 Figure 1: Predicted probability of NSIs based on race and immigrant status among women (N ¼ 11,610). women to experience NSIs; 25.4 per cent of the men and 32.3 per cent of the women reported NSIs. Moreover, the patterns were different for men and women based on race and immigration status. For men, immigrants were less likely to report of experiencing NSIs, regardless of race. For women, the interaction between race and immigration status was significant: racialised Canadian-born women were more likely to report of experiencing NSIs than racialised immigrant women, whilst immigration status had no effect on white women’s likelihood to experience NSIs. The results indicated the importance of accounting for intersecting identities when studying NSIs and their effects. They also emphasised the need to tailor educational efforts to mitigate NSIs across gender, race and immigration status in different family and societal settings in Canada. Whilst examining the intersectional identities of race and immigration status across genders, immigration status becomes an important factor for experiencing NSIs among men. Immigrant men were less likely to report of experiencing NSIs than Canadian-born men. This finding is consistent with the previous research (Nguyen, 2017), which suggested that native-born men may experience higher rates of NSIs than immigrant men, owing to the greater variety of native-born men’s social networks, including their close and extended families. Immigrant men, on the other hand, are more likely to establish ethnocentric social relationships; therefore, their social networks may be more homogeneous than their Canadian-born counterparts (Harell et al., 2017; Gereke et al., 2020;). This finding contrasts the common belief that immigrant men are more likely to experience NISs because of xenophobia and cultural differences. Xenophobia may play a less significant role in NSI since it only measures Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 14 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. close relationships (such as family and friends) instead of encounters with acquaintances and strangers. If immigrant men tend to have relationships within their immigrant communities, it is less likely for them to experience chronic negative interactions stemming from xenophobia in these contexts. Moreover, for many immigrants, migration is a conscious decision that involves ‘selection’ of their social surroundings. When they leave their home countries, immigrants can keep a distance from toxic family relationships or friendships, whilst selectively maintaining some positive relationships by bringing some family members over or maintaining transnational ties (Zhou et al., 2019). They can also ‘reset’ their social relationships through a selective process in the host country. So, instead of being stuck with negative interactions, the migration process may assist immigrants in building a social network that is more pleasant than the one they had before migration. Previous research has found that perceived identity expression may play important roles in daily interactions and social inclusion (Sønderlund et al., 2017). Our study found no significant difference in NSIs between white Canadian-born women and white immigrant women. It is possible by the fact that white immigrant individuals still visibly belong to the dominant racial group in Canada shields them from NSIs. In contrast, our results revealed that racialised Canadian-born women reported the highest level of NSIs of all women groups. One explanation for this could be that racialised Canadian-born women frequently engage in daily interactions that arise out of obligation and bicultural expectations, such as providing support to or receiving advice from parents, family, relatives, siblings and significant others. These social interactions sometimes provide emotional support, but they may involve social pressure and unrealistic gender role expectations, resulting in extra burdens and mental health issues among racialised Canadian women (Offer and Fischer, 2018). It also could be that racialised Canadian women felt challenges in social inclusion and identity expression in Canadian society. Future studies should further elucidate the meanings and causes of negative interactions and the role of gender- and cultural-based expectations to further explain this pattern. The study investigated the intersection of race, immigration and gender. The added layer of immigration in our analysis revealed a surprising result: among all women groups, racialised immigrant women showed the lowest level of NSIs. This finding could be explained by the fact that racialised immigrant women may not perceive social conflicts in their daily lives as negative or chronic (Rezazadeh and Hoover, 2018). Conflicts with family members and significant others may be redefined as opportunities to negotiate new gender roles and cultural expectations, which affects their perception of whether these interactions should be regarded as NSIs (Rezazadeh and Hoover, 2018). Moreover, previous research has indicated that some racialised immigrant women may have Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 15 of 22 encountered challenges before arriving in Canada; the atmosphere of multiculturalism and gender equality in a relatively liberal country such as Canada may provide them with different experiences of social interaction (Sadeghi, 2008; Charpentier and Queniart, 2017). The current results should also be interpreted carefully due to social desirability bias. Previous studies have discussed that self-report questions are vulnerable to social desirability bias because participants from different cultural backgrounds, such as individualistic or collectivistic countries, are likely to over- or under-report their experiences. For example, previous studies have found that immigrants from collectivistic countries, such as Japan and Korea, are likely to over-report socially desirable attributes (Kitchen et al., 2015; Kim and Kim, 2016). Such limitations have also been documented with gender differences; previous literature has found that men were more likely than women to under-report their actual experiences due to social desirability bias (Merrill et al., 1997). Therefore, our participants with previous characteristics mentioned may not have reported their actual experiences or may have interpreted statements differently, leading to misclassified responses. To minimise social desirability bias in reporting NSIs, future research should consider designing non-judgemental questions, assuring anonymity or launching questionnaires online (Joinson, 1999). Asking indirect questions may be another approach to exploring NSIs: for instance, asking about the general experiences of a person in their society or ethnic group, rather than asking for participants to reveal their actual attitudes (Fisher, 1993). Although not focal to our discussion, the variance in NSIs only accounted for 5 per cent in the men’s model and 8 per cent in the women’s model. Other variables may need to be measured to further understand NSIs in Canada. Given that the concept of NSIs may also represent societal and cultural regulations that force people to stay in a relationship which produces discomfort, and which may deteriorate their mental well-being. Hence, more studies could be done to explore the impact of societal and cultural regulations on NSIs across different cultural contexts and settings. Previous research has suggested that developing mutually supportive interactions might be a starting point to improve a stressful social relationship (Offer and Fischer, 2018). Implications for social work practice Social work practitioners work with individuals from diverse backgrounds. From a systems perspective (Friedman and Allen, 2011), social workers in various areas of practice need to address clients’ quality of their daily life interactions with others, as NSIs were related to various mental health and health outcomes (Fiorillo and Sabatini, 2011; Berry and Hou, 2019). Consistent with the previous studies (e.g. Fiorillo and Sabatini, 2011; Sun et al., 2020), we have found that the quality of social Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 16 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. interactions is dependent on social identities, which reflects some bigger structural and systemic issues. There are several practice implications from the results of this study. First, social workers should recognise the capacities and strengths possessed by immigrants. Despite experiencing xenophobia and the loss of social capital during the migration process (Putnam, 2007; Harell et al., 2017), immigrants, except for white immigrant women, reported lower levels of NSIs for both men and women. Hence, in social work practice, in addition to addressing systemic barriers and oppression, practitioners should also acknowledge the role of immigrant communities and choose close relationships as protective factors and sources of resiliency. Secondly, this study illuminates the importance of using an intersectional lens to understand individuals’ surroundings and social relationships. For instance, the difference in the salience of race across genders suggests that it is crucial to explore the interplay between racism and culturally embedded gender role expectations to understand the social experiences among racialised women. Therefore, social workers should tap into various social identities and their roles in an individual’s social environment when working with their clients. Finally, specific intervention strategies can be considered based on different intersecting social identities. For example, as race intersects with immigration status for women, programmes for the education and support of racialised women should address microaggressions related to gender role expectations for women, race and family background (e.g. as a second- or third-generation immigrant). Study limitations In addition to this study’s strengths in using a nationally representative cross-sectional survey, the study’s limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, as the data are cross-sectional, causal associations cannot be established. Secondly, the single, dichotomous item of NSIs focused only on general experiences and did not provide insight into NSIs related to any particular relationship, such as relationships with friends and family. Notably, researchers have argued that single-item measures can be reliable when the aim of the research is to assess a global construct (Gardner et al., 1998; Allan et al., 2022). Given that we are interested in the general assessment of NSI, the use of the single-item measure can still be appropriate. Thirdly, all measures were self-reported and were therefore subject to social desirability bias. Thus, some participants who had encountered NSIs may not have reported their actual experiences or may have interpreted the statement differently, leading to misclassified responses. Fourthly, racialised groups are heterogeneous in their cultural or gender expectations. Due to the limitations of the data-set, we were unable to use more detailed categories of Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 17 of 22 racial/ethnic identities for analysis; differences among various ethnic–racial groups were not studied. More research should be done to further understand the association between intersecting social identities and NSIs within different racial/ethnic communities in Canada. Fifthly, the 2012 CCHS-MH was conducted either in English or French; the prevalence of NSIs may be underestimated among immigrant populations due to language barriers. Sixthly, the data-set was collected in 2012, so the landscape and experiences of individuals with intersectional identities might be different from the present day. Therefore, future research should employ a similar research design to examine the differences in NSIs across intersecting social positions as well as over different time periods. Lastly, all data were collected in Canada; therefore, these findings may be insufficient for understanding the relationship between intersecting social identities and NSIs for individuals living in a different cultural context/country with different demography and policies. Conclusion Guided by an intersectional framework and based on a nationally representative sample, this study has provided a novel and nuanced understanding of how NSI affects mental well-being. Our results indicate the importance of the intersecting identities of gender, race and immigrant status and their impact on NSIs. Future research should explore the nuances of NSIs among different populations, such as individuals’ experiences in different contexts, and the causes of NSIs. To improve the quality of social interactions and, ultimately, the mental well-being of clients, service providers should adopt an intersectional lens to gain insight into the interpersonal experiences of their clients, identify the high-quality social relationships clients may obtain from their communities and close networks and design targeted interventions emphasising experiences and contextual factors of social inclusion and racialised identity expression. Acknowledgements A special thanks to Dr Colin Gorrie for writing support and brainstorming. Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest. References Berry, J. W. and Hou, F. (2019) ‘Multiple belongings and psychological wellbeing among immigrants and the second generation in Canada’, Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement, 51(3), pp. 159–70. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 18 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. Buchanan, N. T., Settles, I. H., Wu, I. H. C. and Hayashino, D. S. (2018) ‘Sexual harassment, racial harassment, and wellbeing among Asian American women: An intersectional approach’, Women & Therapy, 41(3–4), pp. 261–80. Buckley, T. R. (2018) ‘Black adolescent males: Intersections among their gender role identity and racial identity and associations with self-concept (global and school)’, Child Development, 89(4), pp. e311–e322. Charpentier, M. and Queniart, A. (2017) ‘Aging experiences of older immigrant women in Quebec (Canada): From deskilling to liberation’, Journal of Women & Aging, 29(5), pp. 437–47. Collins, P. H. (2000) ‘Gender, black feminism, and black political economy’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 568(1), pp. 41–53. Crenshaw, K. (1989) Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp. 139. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/ 9780429499142-5. Croezen, S., Picavet, H. S. J., Haveman-Nies, A., Verschuren, W. M. M., de Groot, L. C. P. G. M. and van’t Veer, P. (2012) ‘Do positive or negative experiences of social support relate to current and future health? Results from the Doetinchem Cohort Study’, BMC Public Health, 12(1), p. 65. Eidelman, P., Jensen, A. and Rappaport, L. M. (2019) ‘Social support, negative social exchange, and response to case formulation-based cognitive behavior therapy’, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(2), pp. 146–61. Evans, C. R. and Erickson, N. (2019) ‘Intersectionality and depression in adolescence and early adulthood: a MAIHDA analysis of the national longitudinal study of adolescent to adult health, 1995–2008’, Social Science & Medicine (1982), 220, 1–11. Fiori, K. L., Windsor, T. D., Pearson, E. L. and Crisp, D. A. (2013) ‘Can positive social exchanges buffer the detrimental effects of negative social exchanges? Age and gender differences’, Gerontology, 59(1), pp. 40–52. Fiorillo, D. and Sabatini, F. (2011) ‘Quality and quantity: The role of social interactions in self-reported individual health’, Social Science & Medicine (1982), 73(11), pp. 1644–52. Fisher, R. J. (1993) ‘Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning’, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), pp. 303–15. Friedman, B. D. and Allen, K. N. (2011) ‘Systems theory’, Theory & Practice in Clinical Social Work, 2(3), pp. 3–20. Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., Dunham, R. B. and Pierce, J. L. (1998) ‘Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: An empirical comparison’, Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58(6), pp. 898–915. Gereke, J., Schaub, M. and Baldassarri, D. (2020) ‘Gendered discrimination against immigrants: Experimental evidence’, Frontiers in Sociology, 5(59), pp. 59–10. Ghavami, N. and Peplau, L. A. (2013) ‘An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes: Testing three hypotheses’, Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1), pp. 113–27. Gonçalves, M. and Matos, M. (2020) ‘Interpersonal violence in immigrant women in Portugal: An intersectional approach’, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 18(1), pp. 22–41. Gulliver, T. L. and Fowler, K. (2022) ‘Exploring social context and psychological distress in adult Canadians with cannabis use disorder: To what extent do social Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 19 of 22 isolation and negative relationships predict mental health?’, The Psychiatric Quarterly, 93(1), pp. 311–23. Guruge, S., Thomson, M. S., George, U. and Chaze, F. (2015) ‘Social support, social conflict, and immigrant women’s mental health in a Canadian context: A scoping review’, Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(9), pp. 655–67. Harell, A., Soroka, S. and Iyengar, S. (2017) ‘Locus of control and anti-immigrant sentiment in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom’, Political Psychology, 38(2), pp. 245–60. Isakov, A., Fowler, J. H., Airoldi, E. M. and Christakis, N. A. (2019) ‘The structure of negative social ties in rural village networks’, Sociological Science, 6, pp. 197–218. Joinson, A. (1999) ‘Social desirability, anonymity, and Internet-based questionnaires’, Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers: a Journal of the Psychonomic Society, Inc, 31(3), pp. 433–8. Kallman, M. E. (2019) ‘The “male” privilege of White women, the “White” privilege of Black women, and vulnerability to violence: An intersectional analysis of Peace Corps workers in host countries’, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 21(4), pp. 566–94. Kitchen, P., Williams, A. M. and Gallina, M. (2015) ‘Sense of belonging to local community in small-to-medium sized Canadian urban areas: A comparison of immigrant and Canadian-born residents’, BMC Psychology, 3(1), p. 28. Kim, S. H. and Kim, S. (2016) ‘National culture and social desirability bias in measuring public service motivation’, Administration & Society, 48(4), pp. 444–76. Kim, H. K. and McKenry, P. C. (1998) ‘Social networks and support: A comparison of African Americans, Asian Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanics’, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 29(2), pp. 313–34. Kim, I. H., Choi, C. C., Urbanoski, K., Park, J. and Kim, J. M. (2021) ‘Analysis of the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health demonstrates employment insecurity to be associated with mental illness’, Medicine, 100(50), p. e28362. Krause, N. (2005) ‘Negative interaction and heart disease in late life: exploring variations by socioeconomic status’, Journal of Aging and Health, 17(1), pp. 28–55. Krause, N., Newsom, J. T. and Rook, K. S. (2008) ‘Financial strain, negative social interaction, and self-rated health: Evidence from two United States nationwide longitudinal surveys’, Ageing and Society, 28(7), pp. 1001–23. Lincoln, K. D., Chatters, L. M. and Taylor, R. J. (2003) ‘Psychological distress among black and white Americans: Differential effects of social support, negative interaction and personal control’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), pp. 390–407. Lincoln, K. D., Chatters, L. M. and Taylor, R. J. (2005) ‘Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans’, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 67(3), pp. 754–66. Lindsay, K. (2015) ‘Beyond “model minority,” “superwoman,” and “endangered species”: Theorizing intersectional coalitions among black immigrants, African American women, and African American men’, Journal of African American Studies, 19(1), pp. 18–35. Merrill, S. S., Seeman, T. E., Kasl, S. V. and Berkman, L. F. (1997) ‘Gender differences in the comparison of self-reported disability and performance measures’, The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 52(1), pp. M19–M26. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 20 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al. Morgenshtern, M. (2019) “My family’s weight on my shoulders”: Experiences of Jewish immigrant women from the Former Soviet Union (FSU) in Toronto’, Social Sciences, 8(3), p. 86. Nakash, O., Tsahi, H., Gali, M. and Shay, A. (2021) ‘Social network and quality of life among older adults: the moderating role of immigrant status’, Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 58(2), pp. 33–40. Ngoubene-Atioky, A. J., Lu, C., Muse, C. and Tokplo, L. (2020) ‘The influence of intersectional identities on the employment integration of Sub-Saharan African women immigrants in the U’, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 18(1), pp. 75–94. Nguyen, A. W. (2017) ‘Variations in nocial network type membership among older African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites’, The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(4), pp. 716–26. Noh, J. W., Kim, K. B., Park, J., Hong, J. and Kwon, Y. D. (2017) ‘Relationship between the number of family members and stress by gender: Crosssectional analysis of the fifth Korea national health and nutrition examination survey’, PLoS One, 12(9), pp. e0184235. Offer, S. and Fischer, C. S. (2018) ‘Difficult people: Who is perceived to be demanding in personal networks and why are they there?’, American Sociological Review, 83(1), pp. 111–42. Offer, S. (2020) ‘They drive me crazy: Difficult social ties and subjective wellbeing’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 61(4), pp. 418–36. Offer, S. (2021) ‘Negative social ties: Prevalence and consequences’, Annual Review of Sociology, 47(1), pp. 177–96. Patterson, A. C. and Veenstra, G. (2016) ‘Black-White health inequalities in Canada at the intersection of gender and immigration’, Canadian Journal of Public Health, 107(3), pp. E278–84. Pellegrini, V., De Cristofaro, V., Salvati, M., Giacomantonio, M. and Leone, L. (2021) ‘Social exclusion and anti-immigration attitudes in Europe: The mediating role of interpersonal trust’, Social Indicators Research, 155(2), pp. 697–724. Putnam, R. D. (2007) ‘E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize lecture’, Scandinavian Political Studies, 30(2), pp. 137–74. Rezazadeh, M. S. and Hoover, M. L. (2018) ‘Women’s experiences of immigration to Canada: A review of the literature’, Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 59(1), pp. 76–88. Rogers, L. O., Scott, M. A. and Way, N. (2015) ‘Racial and gender identity among Black adolescent males: An intersectionality perspective’, Child Development, 86(2), pp. 407–24. Sadeghi, S. (2008) ‘Gender, culture and learning: Iranian immigrant women in Canadian higher education’, International Journal of Lifelong Education, 27(2), pp. 217–34. Sherman, J. (2017) ‘“Stress that I don’t need”: Gender expectations and relationship struggles among the poor’, Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(3), pp. 657–74. Sneed, R. S. and Cohen, S. (2014) ‘Negative social interactions and incident hypertension among older adults’, Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 33(6), pp. 554–65. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 NSIs and Intersecting Identities in Canada Page 21 of 22 Sunderland, A. and Findlay, L. C. (2013) ‘Perceived need for mental health care in Canada: Results from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health’, Health Reports, 24(9), pp. 3–9. Sønderlund, A. L., Morton, T. A. and Ryan, M. K. (2017) ‘Multiple group membership and wellbeing: is there always strength in numbers?’, Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1038. Statistics Canada. ‘(2013a) Canadian Community Health Survey—Annual Component, 2012.’, available online at: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function¼ getSurvey&Id¼135927 (accessed May 16, 2021) Statistics Canada. (2013b) Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health (CCHS), available online at: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function= getSurvey&Id=119789#a2 (accessed May 16, 2021) Statistics Canada. (2017) Immigration and ethnocultural diversity: Key results from the 2016 census, available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/ 171025/dq171025beng.htm (accessed May 16, 2021) Statistics Canada. (2021) Census of Population, available online at: https://www23.stat can.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3901 (accessed May 16, 2021) Sun, J., Harris, K. and Vazire, S. (2020) ‘Is wellbeing associated with the quantity and quality of social interactions?’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(6), pp. 1478–96. Turner, R. J. and Lloyd, D. A. (2004) ‘Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults: Racial and ethnic contrasts’, Archives of General Psychiatry, 61(5), pp. 481–8. Umberson, D., Williams, K., Thomas, P. A., Liu, H. and Thomeer, M. B. (2014) ‘Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health’, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), pp. 20–38. Urbanoski, K., Inglis, D. and Veldhuizen, S. (2017) ‘Service use and unmet needs for substance use and mental disorders in Canada’, Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 62(8), pp. 551–9. van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2007) ‘Cultural and gender differences in gender-role beliefs, sharing household task and child-care responsibilities, and wellbeing among immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands’, Sex Roles, 57(11–12), pp. 813–24. Veenstra, G., Vas, M. and Sutherland, D. K. (2020) ‘Asian-White health inequalities in Canada: Intersections with immigration’, Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(2), pp. 300–6. Williams, S. L. and Fredrick, E. G. (2015) ‘One size may not fit all: The need for a more inclusive and intersectional psychological science on stigma’, Sex Roles, 73(9–10), pp. 384–90. Wilson, R. S., Boyle, P. A., James, B. D., Leurgans, S. E., Buchman, A. S. and Bennett, D. A. (2015) ‘Negative social interactions and risk of mild cognitive impairment in old age’, Neuropsychology, 29(4), pp. 561–70. Xu, L. and Chi, I. (2013) ‘Acculturative stress and depressive symptoms among Asian immigrants in the United States: The roles of social support and negative interaction’, Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(3), pp. 217–26. Zhou, Y. R., Watt, L., Coleman, W. D., Micollier, E. and Gahagan, J. (2019) ‘Rethinking “Chinese community” in the context of transnationalism: The case of Chinese economic immigrants in Canada’, Journal of International Migration and Integration, 20(2), pp. 537–55. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/advance-article/doi/10.1093/bjsw/bcac224/6874793 by National Taiwan Normal University user on 12 December 2022 Page 22 of 22 Deng-Min Chuang et al.