208

C hapter 6

FRAMEWORK

FOR A SEXUAL ETHIC

Just Sex

TUST LOVE

Yet the underm ining of sex and love is not a necessary consequence of a "law " of justice. Like W. H. Auden we m ight demur:

"Law is the o ne all gardeners observe___Law is the wisdom of the

old, T h e im potent grandfathers shrilly sco ld . . . Law, says the priest

with a priestly lo o k . . . is the words in my priestly book— Law, says

the judge. . . is T h e Law." Bu t lovers shyly propose th at the law is

"Like love I s a y . . . Like love we ca n 't com pel or fly, Like love we often

weep, Like love we seldom keep."1 T h e law of justice need carry none

of these m eanings, however, as I hope to show.

Ju s tice

I

T

is

n o

s u r pr is e

that the ethical framework I propose for the

sexual sphere of hum an life has to do with justice and with love.

I have been m oving steadily to this all along. It is also no surprise

that I propose, finally, a framework that is not ju stice an d love, but

justice in loving and in the actions w hich flow from that love. T he

m ost difficult question to be asked in developing a sexual ethic is

not w hether th is or that sexual act in the abstract is m orally good,

but rather, w hen is sexual expression appropriate, morally good and

just, in a relationship of any kind. W ith what kinds of m otives, under

w hat sorts of circum stances, in what forms of relationships, do we

render our sexual selves to one another in ways th at are good, true,

right, and just?

Arguing th at justice and love should be put together in th e ways

I suggest m ay be counterintuitive. Indeed, strong objections could

be raised: m any w'ill say that to m ake justice a requirement for love

underm ines to o m any understandings of love, especially rom antic

and sexual love. It introduces a kind of "tyran ny" of justice into the

glory of love. I t rcduccs sex to a contract or to som e kind of measure

that is unsuited to w hat sexuality is. It is too harsh a discipline for the

spontaneity o f love, the passion of sexual desire, and the intim acies

marked by jo y while safeguarded by privacy. Wc do not need one

m ore way for heavy-handed socially constructed norm s to shape and

to control personal relations, to the advantage of som e but perhaps

the detrim ent of all.

207

Justice, of course, can mean m any things. M y use of the term is

based sim ply on the classic fundam ental "form al" m eaning: to render to each h er or h is due. T h is is a m ore general no tion of justice

than our usual focus on certain kinds o f justice — for example, distributive justice, legal justice, retributive justice. But it is at the heart

of all form s o f justice, and when it com es to sexual justice, th is basic

m eaning rem ains relevant.

"Form al" m eanings, however, do not go very far in telling us w hat

really is just. T hey provide direction, but not sufficiently specific

content to be of m uch help in guiding our behaviors. Th ey do not,

in short, tell us w hat is "d u e." T h is is why whole system s of ju stice have, in fact, been unjust. W ithout critical spécification of what

"due" m eans, there can be — in the n am e of justice — system s in

which slavery is endorsed, certain groups of persons are m arginalized, and w om en and m en are "legitim ately" treated unequally It

is presumed and som etim es theoretically defended that it is "due"

som e individuals to be treated as m asters and "due" others to be

treated as slaves; it is right and just to place som e persons on the

m argins o f society because th is affirm s what is due th em and what

is due others; it is due women to be assigned certain roles and places

in social hierarchies because th is accords with what they are.

Although I am aware that there arc m any ways to spccify the

requirements of justice — through social contracts, longstanding

1.

W. H . A u d en , "L a w Lik e L ov e," in S e le c t e d P o etry o f W. H. A u d e n , 2 n d ed. (New

York: V in tag e B o o k s, 1 9 7 0 ), 6 2 - 6 4 .

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

210

custom s, certain kinds of noncontradictory reasoning— I move forward here w ith the perspective I have already introduced. I begin,

To acknowledge all of these difficulties and possibilities should make

us cautious in our interpretations of the concrete reality of persons,

then, by translating the formal m eaning of ju stice (render to each

w hat is due) in to the following basic form al ethical principle: Persons

but it does n o t contradict the requirem ent of discerning as b est we

can the reality that is part of w hat every person is or shares in some

form , the reality of persons as persons. Love itself may lead us to

an d groups o f p erson s ou ght to h e affirm ed according to th eir con crete

reality, ac tu al a n d p o te n tia l Depending on their circum stances and

the nature of their relationships, the concrete reality of persons can

include som e particularly relevant aspect of their reality — as, for

exam ple, buyer or lender, parent or child, professional caregiver or

patient, com m itted m em ber of a voluntary association, and so on.

But even a form al principle like this one is insufficient for discerning

w hat really is just. We therefore need to go on to determ ine ''m aterial" ethical principles of justice — that is, principles that do specify

and substantiate w hat is "due/ ' that do give substantive content to a

form al principle. If, as I have argued in the previous chapter, a formal

principle for justice in loving is to love in accord w ith the concrete

reality of persons, th en m aterial principles of ju stice will depend on

our interpretation of the realities of persons — their needs, capacities,

relational claim s, vulnerabilities, possibilities.

T h e C o n c rete Reality o f Persons

O ur knowledge o f hum an persons generally, as well as of individual

persons, differs and changes, sincc our interpretations of hum an experience are historical and social. Moreover, there are differences (not

ju st perceptions of differences) in the experienced concrete realities

of individuals and groups — differences that are or ought to be of

trem endous im portance to us. And who can not notice the myriad

nuances o f h um anity that appear in so m any ways in the searching

eyes of the lover?

. . . H ow m any loved your m om ents of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one m an loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face___2

2.

W. B . Y eats, "W h e n You A re O ld ," in T h e C o lle c t e d P o e m s o fW . B. Yeats (New

York: M a c m illa n , 1 9 5 6 ), 4 0 - 4 1 .

TUST LOVE

exam ine our interpretations of th e realities of persons and to test

these interpretations with w hat is available to us in th e sources of

m oral insigh t that w c saw in chapter 5. In this way w c can correct

or embrace th em again.

In general, what 1 propose is an inductive understanding of the

sh ared co n crete reality o f hu m an persons that includes the following:

Each person is constituted with a com p le x structure — embodied,

inspirited, with n eed s for food, clothing, and shelter, and at some

point usually a capacity for procréation; but also with a capacity for

fre e c h o ice and the ability to thin k an d to fe e l.3 Hum an persons are

also essentially relation al — w ith interpersonal and social needs and

capacities to open to others, including God, in knowledge, love, and

desire, as w ell as all the em otional capacities th at we experience,

such as fear, anger, sorrow, hope, joy. Persons exist in th e world, so

that their reality includes their particular history and their location

in social, political, econom ic, and cultural contexts. Further, persons

have some sort of relationship to institution s — w ithout total identification or lim itation to system s and institutions, and som etim es

3.

H ow w e in te rp r e t th is co m p le x stru ctu re w ill m ake a great deal o f d iffere nce in

w h a t w e affirm f o r o u rselv es and o th ers. A s 1 noted in P erson al C o m m itm e n ts , 141

n . 2 : If, fo r e xa m p le , w c th in k th a t e m o tio n s arc th e p rim ary e le m e n t in the hu m an

personality, w c w ill hav e a d iffe ren t view o f h u m a n w ell-be ing th a n if w e th in k th a t

e ach o n e’s re aso n or ra tio n ality is prim ary. Sim ilarly, if w e th in k th a t free ch o ic e is o f

c e n tr a l im p o rtan ce to every p erson, w e w ill w a n t fo r p erso n s so m e th in g q u ite d ifferent

th a n if w c th in k t h a t p e rso n s h av e a p la ce in a n o rg a n ic so ciety w h e re th e ir r o le s arc

pre scribe d and th e im p o rtan ce o f freedom is negligible. I c a n n o t resolve su ch d ifferences

here , thou g h m y overall th eo ry in th is bo o k n o t on ly r aise s th e q u e stio n s bu t a tte m p ts

to offe r a co h e ren t view o f so m e m o ral req u ire m e n ts b ased o n an in te rp re tatio n o f the

re ality o f p erso n s. I sh ou ld add, also, th a t I am n o t add ressing h e re th e q u estio n o f w ho

sh ou ld b e tre a ted as p e rson s if n o t ev eryone w e th in k of a s a p e rso n h a s th e p o ssibility

o f exe rcising th e cap acitie s I a m describin g (such as th in k in g , ch o osin g , procreating,

e tc.). T o describe w h a t b elongs to "p erso n h o o d " is a d iffe ren t ta s k from id entifyin g the

pool o f e n tit ie s t h a t are to be treated a s p e rso n s. For th e latter, all th o se b o rn o f p erson s

ca n b e included , w hatever th e ir p re sen t cap acitie s o r ca p a cities fo r d ev elo pm en t. B ut

th is inv o lv e s a d iscu ssio n of an o th e r se t o f issu e s th a n th e o n es th a t I a m addressing

in th is volume.

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

211

212

TUST LOVE

w ith only a rejecting relationship. And the reality of persons includes

n ot only their present actuality but their positive potentiality for development, for h um an and individual flourishing; as well as their

Indeed, such considérations may illum inate each one's concrete individual reality and m ay reveal som e of the central requirem ents of

love, and sexual love, of any person as a person. O b lig atin g features"

vulnerability to dim inishm ent. Finally, every person is unique as

well as a com m o n sharer in humanity. A ju st love of persons will

take all of th ese aspects of persons into account, though som e will

be m ore im portant than others, depending on the context and the

of persons constitute the basis of requirem ent to respect persons,

in whatever way wc relate to them , sexually or otherwise. Autonomy and relationality in particular are "obligating features" because

nature of a relationship.

O bligating Features o f Personhood

Contem porary understandings of th e hum an person lead us to a

special focus on at least two basic features of hum an personhood:

features that can be called au ton om y and relationality.4 "Basic" here

does not im ply th a t we can understand fully w hat the "essen ce" of

the hum an person is. There is a wariness in contem porary W estern thought about even acknowledging that there are "essences" to

be known, le t alone essences th at w e can k now My attem pt to delineate features of w hat it m eans to be a hum an person recognizes

the partiality o f our knowledge, the historical changeability of knowledge and the variations o f hum an self-understandings from culture to

culture and across tim e. N onetheless, it seem s to m e th a t we cannot

reasonably assert either that we know nothing at all about the hum an

person as person, or that we have nothing of a shared knowledge in

this regard.

It is not necessarily to abstract from the concrete reality of individual persons to consider w hat is central to the h um an personality.

4.

M y a p p roa ch m ig h t a t le a st m ee t th e p rag m atic level o f "stra te g ic e sse n tia lism ,"

in t h e se n se in w h ich S eren e Jo n e s and o th e rs u s e th is te r m . Se e S e ren e Jon es, Fem -

inism and Christian Theology: Cartographies o f Grace (M in n e a p o lis: F o rtr e ss , 2 0 0 0 } .

Y et m y co n ce rn is n o t p rim a rily w ith sp e cu la tiv e know led ge; it is w ith th e kin d of

know led ge t h a t w ill te ll us w h a t is h a rm fu l and w ha t helpful in h u m a n life. T o so m e

e xten t, th is co rre sp on d s w ith Beverly H arriso n 's v iew o f ju s tic e a s a p rim a ry m e tap h or

o f rig ht rela tio n sh ip , o n e th a t sh a p e s th e t elo s o f a good co m m u n ity and a n im ates

C h ristia n m oral se n sib ilitie s. S e e B everly W ild un g Fla rriso n , Ju s tic e in t h e M aking:

F em in is t S o c ia l E th ic s (L ouisville: W e stm in ste r Jo h n K no x, 2 0 0 4 } , 1 6 . I m ay b e even

clo se r to M a rth a N u ssb a u m 's d elin e atio n o f h u m a n "fu n c tio n a l c a p a b ilitie s " approach,

sin ce N u ssb au m and I sh a re n o t o n ly a so cia l e th ica l a im b u t a be lief in so m e rockb o tto m ca p ab ilities and n eed s fo r h u m a n be in gs th a t d em an d resp e ct and a ffirm atio n .

S e e M a rth a C . N u ssb a u m , S e x a n d S o c ia l Ju s t ic e (N ew York: O xford U n iv e r sity Press,

1 9 9 9 ), 4 1 - 4 2 .

they ground an obligation to respect persons as ends in them selv es

and forbid, therefore, the use of persons as m ere m eans.5 T h is claim

bears exploration. I could argue here that persons arc of unconditional value, ends in themselves, because they are created so and

loved so by G od, who reveals to us a com m and and a call to treat

one another as ends, and not only as m eans. M y approach is in an

im portant sense warranted by this belief, and I am attem pting to

provide a way of understanding it. Yet I also think th at a plausible

elaboration of what characterizes hum ans — created and beloved as

we are — is also accessible to those w ho stand in diverse faith traditions or no faith tradition at all. So I continue to explore and to

argue on the basis of experience and our system atic understandings

of experience: First, persons are ends in themselves because they are

autonomous in the sense th at they have a capacity for fre e choice.

Why? Bccausc freedom of choice as w c cxpcricncc it is a capacity for

self-determ in ation as embodied, inspirited beings, w hich m eans a capacity to choose n ot only our own actions but our ends and our loves.

It is a capacity therefore to determ ine the m eaning of our own lives

and, w ithin lim its, our destiny. It is a capacity to set our own agenda,

w hether it is on e that is good for us and others or not. H ence, for me

to treat another hum an person as a mere m eans is to violate her insofar as she is autonomous; it is to attem pt to absorb her com pletely

into my agenda, rather than rcspccting the one that is her own.

Secondly, a hum an capacity for relationship (or relationality) also

grounds an obligation to respect persons as ends in themselves. W hy

5.

By iden tify in g p e rso n s as "e n d s in th e m selv e s" I do n o t a ssu m e th a t they are

su fficie n t in th e m se lv e s o r th at we ca n u nd erstand th e m in a v acu u m , a ll b y the m se lves.

M y secon d o b lig atin g featu re sh o w s th is exp licitly. M o re t h a n th is, however, I consid er

it q u ite p ossible t o e x ist as a b eing th a t is an en d it its e lf and y et to e x is t relativ e t o God.

S e c Farley, "A F e m in is t V ersio n o f R espect fo r P e rso n s," fo u r n a l o f Fem in ist S tu dies in

R eligio n 9 (Spring /Fall 1 9 9 3 ): 1 8 3 - 9 8 ; also , Farley, C o m p a s s io n a te R e s p e c t: A F e m im st

A p p r o a c h t o M e d ic a l E th ics a n d O th e r Q u es tio n s (N ew York: P au list, 2 0 0 2 ), 3 6 - 3 9 .

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

214

again? It is generally acknowledged that individuals do not ju st survive or thrive in relations to others; they cannot exist without some

have stretched our being through our knowing love and our loving

knowledge. In knowledge and love, and in being know n and being

form of fundam ental relatedness to others/’ T h is generally implies

dependence o n others, y et the cap acity for relation is a capacity to

reach beyond ourselves to other beings, especially to other persons.

loved, w c arc centered both w ithin and w ithout — both in what

we love and in ourselves, as we hold w hat we love in our hearts.

We are who we are n ot only because we can to som e degree determine

ourselves to be so by our freedom but because we are transcendent of

IUST

LOVE

T h e capacity to love one another and all things, and to love w hat

is sacredly transcendent and im m anent (that is, the divine), makes

persons worthy of respect. Each and every person is of unconditional

ourselves through our capacities to know and to love. T h e relational

value. Each person is a whole world in herself, yet her world is in

aspect of persons is not finally only extrinsic but intrinsic, the radical possibility of com ing into relation, into union, w ith all that can

w hat she loves. T h is is w hat interiority means for hum an persons,

and w hat it m eans in our relationships one w ith another.8

be known and loved — and especially with other persons, including

God, where union can take the form of com m union, knowing and

being known, loving and being loved. A s such, we are n ot bounded,

ground any norm s we articulate for general ethics or sexual ethics.

not com plete in ourselves once and for all, as if our world could be

closed upon itself. We rem ain radically open to un io n with others,

through knowledge and love; our interior world is transcendent of

itself, though w c hold also a whole world w ithin ourselves. To respect the world that we are and the world we are becoming requires

Freedom and relationality, then, are the obligating features that

Beings with these features ought n ot be completely scooped up into

som eone else's agenda. T h ey ought not be treated as m ere means

but a lso as ends in them selves. Moreover, freedom and relationality as features of hum an persons are profoundly co n n ected w ith one

another: we can n ot grow' in freedom except in som e nurturing relationships; and freedom ultim ately is for the sake of relationships —

respecting ourselves and other persons as ends, n ot only as means.

W hether or n ot pre-modern, modern, or postm odern philosophies

the loves, th e relationships we finally choose to identify with in our

deepest selves. Together autonom y (or freedom) and relationality also

find settled selves or unsettled selves (a series of selves with n o continuity or anchor), it is awe before the world of the self that can

generate respect and even reverence, if only we see it.7

provide the co n ten t for m ost of the basic norm s for right loving and

the basic m oral norm s for sexual ethics. N orm s for a general sexual

A nother way to say all of th is is th a t as persons we are term in al

cen ters , ends in ourselves, b ec au s e in s o m e w ay w e b oth transcend

ourselves an d y et belon g to ourselves. It is by our freedom that we

transcend ourselves, introduce som ething new, beyond our past and

present. By our freedom, w c also possess ourselves; our selves and

our actions are in som e sense our own. Besides the place of freedom

in self-transcendence and self-possession, it is also in and through

our relationality th at we as hum ans both transcend and possess ourselves; we belong to ourselves yet we belong to others to whom we

ethic, then, m ust n ot only satisfy th e demands of these two features

of personhood; they m ust serve to specify more clearly the meaning

of the features.

Despite all th at I have said above, it m ay n ot be superfluous to

draw one general conclusion here regarding norm s for sexuality. In

chapter 4 I spoke o f the m ultiple meanings and aim s, or motivations,

that are possible for hum an sexual activity and relationships — some

distortivc and destructive, som e accurate and creative. Now, given

our explorations of just love and desire, ju st sexual love and desire,

wc can say that the aim s of sexuality ought to accord w ith, or at the

very least, n o t violate the concrete reality of hum an persons. If they

6 . A lth o u g h I a m in te rp r etin g re la tio n a lity to re fe r t o rela tio n by know ledge and

love, I d o n o t th e re by deny t h e n e cessa ry re lated n css th a t in clu d es d epend ence o n God

for o n e 's very e xiste n ce .

7. Se e Farley, "H o w S h a ll W e Love in a P ostm o d ern W orld ?" A n n u a l o f t h e S ociety

o f C h ristian E th ic s {So ciety of C h r istia n E th ic s, 1 9 9 4 ) , 3 - 1 9 .

8.

I do n o t d e n y a kind of in te rio r ity in all be in g s, or ce rta in ly in higher level

a n im als o th e r th a n h u m a n s. I a m he re, however, ta lk in g abou t h u m an p e rso n s, for

w h ich th e re is a k in d o f in terio rity th a t appears to be d istin ctiv e to th e species.

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

216

do so accord, they will not be destructive or distortivc. Also in chapter 4 I identified elem ents th at characterize and can belong to m uch

specific n orm s arc not m utually exclusive. Although each of them

emphasizes som ething the others do not, they nonetheless overlap

of hum an sexual experience. T h ese included n ot only em bodiment

and em otion s, but pleasure, desire and love, language and com m un ication, procréation, and power. Pleasure, com m unication, the union

of love and its intim acy, em powerm ent, and a desire for offspring

enough that, as we shall see, som e sexual behaviors and relationships

are governed by more th an one norm . Fourth, since hum ans are em bodied spirits., inspirited bodies, theirs is an embodied autonom y and

TUST LOVE

are each great hum an goods. If sex is an expression of love th a t is

just, then each and all of these can be the aim or part of the aim

an embodied relationality. T h e n orm s th at I will lay out, therefore,

are to be understood as requiring respect for an embodied as well as

inspirited reality. I turn now to the specific norm s that I propose for

of sexual desire and activity.9 W hether they are so in a way that is

a contemporary hum an and C hristian sexual ethic.

ju st will be clearer w hen we identify m ore specific ethical norm s for

sexual activities and relationships. Power, especially in interpersonal

relationships can be, but need n ot be, a great hum an good. W hether

and w hen it is good in sexual relations m ust also be determined by

m ore specific norms.

N o rm s for Ju st Sex

Som e prelim inary clarifications are im portant for understanding the

specific n orm s for a sexual ethic. First, the norm s that I have in mind

are not m erely ideals; they are bottom -line requirem ents. Second, and

as a qualification of th e first, all of th ese norm s adm it of degrees. T h is

m eans th at there is a sense in which they are stringent requirements,

but they are also ideals. In both senses, they are all part of justice.

T h at is, they can be understood in different contexts as norm s of

w hat I shall call "m in im al" or "m ax im al" justice. W hile m inim al

justice is always required, m axim al justice can go beyond this to

w hat is "fitting ." M axim al justice may, in fact, point to an ideal that

exceeds th e exacting requirem ent o f m inim al ju stice.10 Third, the

9.

I a m n o t e sp ou sin g th e view th a t se x u al a ctiv ity ca n be ju stified o n ly w h en it

a im s a t o r is a t le a s t open to th e p o ssibility o f p ro creation . I d iscu ss th is a g ain in the

co n te x t o f o n e o f th e sp e cific n o rm s th a t follow s.

10.

W h at I m e a n by "fittin g " m a y n o t be co m p letely clear. B o th m in im a l and m a xim a l ju s tic e have to do w ith t h e co n cre te rea litie s o f p e rso n s and w h a t is "d u e " th em .

W ith m in im a l ju stic e , w hat is d ue is a b o tto m -lin e strin g en t req u irem en t; m axim al ju s tice in co rp o rate s m in im a l ju stice bu t goes beyond it. How ever, sim ply "g o in g beyond"

m ay n o t m ea n g re ate r ju s tic e . T h e r e arc w a y s in w h ich w c c a n th in k w c a rc exceeding

th e d e m a n d s o f ju s tice , b u t ren dering " m o r e " m a y n o longer be ju stic e a t a ll; it m ay be

in ju stic e if it is n o t fittin g o r ap propriate for an ind iv id ual o r group. I t m a y in fact be

d estru ctive . T h u s , fo r ex a m p le, a te a ch e r m ay go beyond w ha t is ord in arily required by

1. D o N o U njust H a rm

T h e first general ethical norm we m ay identify is the obligation not

to harm persons unjustly.11 T h is is grounded in both of the obligating features of personhood, for it is because persons are persons that

we experience awe of one another and the obligation of respect. "Do

n ot h arm " echoes through the experience of "do not k ill" the other.

T o harm persons m ay be to violate who they arc as ends in th em selves.12 But th ere are m any form s that harm can take — physical,

so m e o f h e r stu d en ts in te rm s o f a ssistan ce ; b u t h e r "g o in g bey o n d " m ay o r m a y n o t be

ju st. E veryth ing d epe nds o n th e co n crete re a lities o f th e stu d e n ts, w h a t is appropriate

in a p ro fession al/stu d e n t relation ship , and w h a t th e tc a c h c r c a n reason ably do, taking

in to acco u n t th e le g itim ate d em an ds o f o th er stu d en ts. S h e may, if sh e provides "to o

m u ch " a ss is ta n c e , be h a rm in g her stu d e n ts be cau se s h e d o e s n o t en cou rag e th eir ow n

cre ativ ity and d e v elo p m e n t o f sk ills. H e n ce , "m a x im a l" ju stice "g o es be yo nd " in ways

th a t a rc app rop riate or fittin g — as w h e n so m e o n e is in te rrib le need, w ith n o p articular

fu rth e r c la im o n so m e o ne else to m e et th a t ne ed, bu t so m e o n e h elp s o u t anyway. He

g oes th e "e x tra m ile " be cau se it is b o th needed and appropriate; it is fittin g fo r the

p e rso n s involved, th e situ atio n , and h is cap ab ilitie s. So m e m ig h t ca ll th is "su p ererogatory," above and beyond an y real m o ra l obligation ; b u t th e re are so m e in s ta n ce s |for

e xam p le, in th e d e m an d s o f friend sh ip as opposed to o rd inary d em and s in re lation to

anyone) w here th e r e re ally is a n o th e r leve l o f o blig atio n , th o u g h n o t as s tr ic t as th e

o b lig a tio n in v o lv ed in m in im a l ju stic e.

11. H a rm " u n ju s t ly " helps to clarify th a t th e in ju n ctio n "d o n o h a r m " is n o t a

g en e ral a bsolu te p ro h ib itio n . W e do h a rm p erso n s w hen th e h a rm is n e ce ssa ry t o bring

abo ut a greate r good. A n exam p le o f t h is is in th e p ra ctice o f m e d icin e . A lm o st every

m ed ical t r e a tm e n t (especially surgery) involves so m e h ar m to a p atie n t, bu t it is a harm

th a t is "ju s tifie d " for a sig n ifican t g reater good.

12. O f co u r se , w e a lso have o b lig atio n s n o t to h ar m o t h e r beings besid es persons.

W c co n sid e r s o m e of th e m to have in trin sic w orth — as, for exam p le , n o n h u m an a n im a ls and the w h o le n etw o rk o f b eing s t h a t co n stitu te our "natu ral e n v ir o n m e n t." I do

n o t w an t h e re t o engage th e d iscu ssion o f w h eth e r so m e o f th e se be ing s arc o f " u n co n d itio n a l" w o rth , tho ugh w h e n th e liv es o f h u m a n p e rso n s co n flict w ith th e lives of

n o n h u m a n b ein g s, I a m read y to sa y th a t th e w o rth o f persons ta k e s priority. T h is is a

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

218

psychological, spiritual, relational. It can also take the form of failure

to support, to assist, to care for, to honor, in ways that are required

by reason of context and relationship. I include all of th ese form s in

well as pornography, prostitution, sexual harassment, pedophilia,

sadom asochism . M ost of these are controversial today, so that they

TUST LOVE

this norm .

In the sexual sphere, "do no unjust harm " takes on particular

significance. Here each person is vulnerable in ways that go deep

cannot be rejected out of hand, judged without assessm ent of their

in justice or justice. M any of these are governed by o ther principles

for a sexual eth ic th at we have yet to explore. I will therefore return

to th em again, though all too briefly, placing th em in the whole of

within. As Karen Lebacqz has said, "Sexuality has to do w ith vulnerability. Eros, the desire for another, the passion th at accom panies

the framework for sexual ethics th at I am proposing.

"D o no u nju st h arm " goes a long way toward specifying a sex-

the w ish for sexual expression, m akes one vulnerable___capable of

being wounded.13 And how m ay we be wounded or harmed? We know

the myriad ways. Precisely because sexuality is so intim ate to persons, vulnerability exists in our em bodim ent and in the depths of

our spirits. D esires for pleasure and for power can become bludgeons

in sexual relations. As inspirited bodies we are vulnerable to sexual

exploitation, battering, rape, enslavement, and negligence regarding

w hat wc know w c m ust do for sex to be "safe sex." As embodied

spirits we are vulnerable to deceit, betrayal, disparity in com m itted

loves, debilitating "bonds" of desire,14 seduction, the pain of unfulfillm ent. We have seen in previous chapters the role sex can play in

conflict, the ways in w hich it is connected w ith sham e, the potential it has for instrum entalization and objectification. We have also

seen human vulnerability in the con text of gender exclusionary practices and gender judgments: "Terrible things arc done to those who

deviate."15

ual ethic, but not far enough. It is necessary to identify additional

principles for a sexual eth ic th at aim s to take account of th e com plex concrete realities o f persons. I said above that autonom y and

relationality, two equally primordial features of hum an persons, provide th e ground and th e content for sexual ethics. Th ey provide a

ground or basis, as we have seen, for the principle that forbids un justifiable h arm . Together they yield six m ore specific and positive

norm s: a requirem ent of free choice, based on th e requirem ent to respect persons-' autonomy, and five further norm s that derive from the

requirement o f respect for persons' relationality.16 H ence, wc move

from our first norm , "do no u njust h a rm " to a second norm for a

sexual ethic: freedom of choice.

2. F ree C on sen t

We have already seen the im portance of freedom (autonomy, or a

A ctions and social arrangem ents that are typically thought to

be harmful in the sexual sphere include all form s o f violence, as

capacity for self-determ ination) as a ground for a general obligation to respect persons as ends in themselves. T h is capacity for

self-determ ination, however, also undergirds a more specific norm.

top ic tor a n o th e r day, however. W h a t I a m co nce rne d w ith h ere is n o t o n ly th a t h u m an s

a re en d s in th e m se lv e s, b u t th a t the y are so be cau se o f th e o b ligating featu re s o f th eir

T h e requirem ent articulated in th is norm is all the m ore grave because it directly safeguards the autonom y of persons as embodied

p e rso n h o o d . I t is th e re fo r e p rec is e ly b e c a u se h u m a n s a re s e lf -tra n sc e n d e n t y e t b elo n g

to th em se lv es t h a t I id en tify and groun d m y n o rm t h a t p ro hib its u n ju s t h arm in g of

them .

13. Lebacqz , "A ppropriate Vu ln erability," 4 3 6 .

14. S e c ic s s ic a B e n ja m in , T h e B on d s o f L o v e: P sy ch oan alysis. F e m in is m , a n d th e

P rob lem o f D om in a tio n (N ew York: P a n th eo n B oo ks, 1 9 8 8 ); and B e n ja m in , " T h e Bonds

of Love: R a tio n al V io le n ce and E ro tic D o m in a tio n ," in T h e Fu ture o f D iffe r e n c e , ed.

H e ste r E ise n ste in and A lic e Jard in e (N ew B ru n sw ick , N J: R utgers U n iv ersity P ress,

1 9 8 5 ), 4 1 - 7 0 .

15. C h ristin e M . K orsgaard, "A N o te o n th e Value of G c n d e r-Id cn tifica tio n ," in

W om en , C u ltu re a n d D e v e lo p m e n t, ed. M a rth a C . N u ssb a u m and Jo n a th a n G lover

(O xford : C la ren d o n P ress, 1 9 9 5 ), 4 0 1 - 3 .

and inspirited, as transcendent and free.171 refer here to the particular obligation to respect th e right of hum an persons to determine

16. Se e be lo w th e diagram o f all the n o rm s o n page 2 3 1 .

17. In so m e ap p ro ach es to m edical e t h ic s, fo r exam ple, th e p rinciple req uiring resp e ct fo r p erso n s red uces to respect for a p erson ’s au ton om y, and th e p rim ary specific

ru le b e co m es th e req u irem en t for in form ed c o n s e n t in re latio n to m ed ical tre atm e n t.

It is a m istak e , how ever; to e q u a te rcsp cct fo r p erso n s w ith resp ect fo r auton om y . T h is

need n o t lessen th e im p o rtan ce o f respect fo r au to n o m y as a n e sse n tial p art o f w hat

re sp ect fo r p e rso n s as p erso n s requires. S e e Farley, C o m p a s s io n a te R es p e c t: A F em in ist

A p p r o a c h t o M e d ic a l E th ics a n d O th e r Q u estio n s (N ew York: P au list, 2 0 0 2 ), 2 2 - 4 4 .

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

219

220

TUST LOVE

their own actions and their relationships in the sexual sphere of their

lives. 18 T h is right or this obligation to respect individual autonomy

sets a m in im um but absolute requirem ent for the free co nsent of

im portant sense coerced you. Similarly, if I make a prom ise to you

w ith no in ten tion of keeping the promise, and you m ake decisions

on the basis o f th is promise, I have deceived, coerced, and betrayed

sexual partners. T h is m eans, of course, that rape, violence, or any

harm ful use of power against unwilling victim s is never justified.

Moreover, seduction and m anipulation of persons who have limited

capacity for choice because of imm aturity, special dependency, or loss

of ordinary power, are ruled out. T h e requirement of free consent,

you.20 Along with the requirem ent of free consent, then, these other

obligations belong to a sexual ethic as well.

Relationality, I have argued, is cquiprimordial with autonom y as

an essential feature of h um an personhood, and along w ith autonomy grounds th e obligation to respect persons as ends in them selves.

then, opposes sexual harassment, pedophilia, and other instances of

disrcspcct for persons' capacity for, and right to, freedom of choice.

Derivative fro m the obligation to respect free consent on the part of

sexual partners are also other ethical norm s such as a requirem ent

Like autonomy, relationality does m ore than ground obligations to respect persons as persons; it specifies the co ntent of th is obligation.

To treat persons as ends and n ot as mere m eans includes respecting

their capacities and needs for relationship. Sexual activity and sexual

for truth-telling, promise-keeping, and respect for privacy. Privacy ,

despite contentions over its legal meanings, requires respect for what

today is nam ed "bodily integrity." "D o not touch, invade, or use" is

the requirem ent unless an individual freely conse nts.19 W hat this

recognizes is th a t respect for embodied freedom is necessary if there

pleasure are in strum ents and modes of relation; they can enhance

relationships or hinder them , contribute to th em and express them .

Sexual activity and pleasure are optional goods for hum an persons in

the sense th at they arc n ot absolute, peremptory goods which could

never be subordinated to other goods, or for th e sake of othe r goods

be let go; but they are, or certainly can be, very great goods, mediating

is to be respect for th e intim acy of the sexual self.

W hatever other rationales can be given for principles of truthtelling and prom ise-keepin g , their violation lim its and h ence hinders

the freedom o f choice of the other person: deception and betrayal are

ultim ately coercive. If I lie to you, or dissem ble when it com es to

com m unicating m y in tentions and desires, and you act on the basis

of w hat I have told you, I have limited your options and hence in an

18. I realize 1 a m intro d u cin g y e t a n o th e r e th ica l te rm here: "r ig h t ." I t goes beyond

th e sco p e of th is v o lu m e t o try t o clarify th is. I a m the re fo re going to assu m e so m e

general u n d e rsta n d in g o f a "rig h t" a s a cla im — w h e th e r legal o r m o ra l, grounded in

th e law, in a so cia l co n tra ct, o r in w h at h u m a n persons are. In m y c o n te x t he re I

acknow led ge m o r a l rights, cla im s th a t p lace m o ral o b lig a tio n s o n o th e rs to respect,

sccu re, and p ro tcc t. So m e o f th ese cla im s c a n a nd ou g ht to be secured a lso by law.

19. A "d o n o t to u c h " ru le h o ld s d ifferently in th e sex u al sp here th a n in th e m edical (a lthough th e y so m e tim e s co m e together, o f cou rse}. I n th e latter, it undergirds

th e req u ire m en t of inform ed c o n se n t for tre a tm e n t, th o u g h it ad m its o f excep tion s

in e a se s o f em ergency , p ublic h e a lth th re a t, and so forth . A s fa r as I know, th e term

"b o d ily in t eg rity " w as first u sed in re la tio n to a u to n o m y (to e sta b lish p e rso nal physical

bound aries) by B e ve rly W ild u ng H a rriso n . Se e h e r "T h e o lo g y o f P ro -C h o ice: A F em in ist

P ersp ectiv e," T h e W itn ess 6 4 (Sep te m b er 1 9 8 1 ): 2 0 ; a lso, A Right to C h o o s e : T ow ar d a

N e w E th ic o f A b or t io n (B o ston: B eacon , 1 9 8 3 ); M ak in g t h e C o n n ec tio n s , cd . C arol S.

R obb (B oston : B eaco n , 1 9 8 5 ), 1 2 9 - 3 1 . N ee d less to say, w hile H arriso n 's appeal t o th e

co n ce p t w as fre q u e n tly in th e c o n te x t of a b o rtion , it h a s m u ch broad e r m e an in g — for

h e r and for o th ers.

relationality and the general well-being of persons.

Hence, insofar as one person is sexually active in relation to another, sex m u st n ot violate relationality, but serve it. Another way of

saying this is th at it is n ot sufficient to respect the free choice of sexual partners. In addition to "do no h arm " and th e requirem ent of free

consent, relationality as a characteristic of hum an persons yields five

specific norm s for sexual activity and sexual relationships: m utuality, equality, com m itm ent, fruitfulness, and w hat I w ill designate in

general term s, "so cial ju stice." For an adequate contem porary sexual

ethic, we need to explore th e m eaning and im plications o f each of

these norm s.

3. Mutuality

Respect for persons together in sexual activity requires m utuality

of participation. It is easy for u s today to sing the songs of m utuality in celebration of sexual love. We are in disbelief when we

20.

T h is is d ifferen t from m ak in g a p ro m ise and th en b e in g u n able to fulfill it,

e ith e r be cau se o f ch ang e in circu m stan ces, w e ak n e ss o n the p a rt of th e prom isor, or

w hatever.

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

221

learn th at it h as n ot always been so. Yet traditional interpretations

of heterosexual sex are steeped in images of the male as active

and the fem ale passive, th e wom an as receptacle and th e m an as

222

TUST LOVE

w hat contem porary philosophers have called a "double reciprocal incarn atio n," o r m utuality of desire and embodied unio n.22 N o one can

fulfillcr, the w om an as ground and the m an as seed. No other in-

deny that sex m ay in fact, serve m any functions and be motivated by

m any kinds o f desire. N onetheless, central to its meaning, necessary

terpretation o f the polarity between the sexes has had so long and

deep-seated a n influence o n m en's and w om en's self-understandings.

for its fulfillm ent, and normative for its m orality w hen it is within

an interpersonal relation is som e form and degree of mutuality.

Today w c th in k such descriptions quaint or appalling, and wc rec-

Yet we have learned to be cautious before too high a rhetoric of

ognize th e danger in them . For despite the seeming contradiction

between the active/passive model of sexual relations and the som e-

mutuality, too m any songs in praise of it. Like active/passive relations, mutuality, too, has its dangers. Insofar as, for example, we

tim e interpretations of w om en's sexuality as insatiable, the model

assum e it requires total and utter self-disclosure, we know that harm

lurks unless sexual relations have matured into justifiable and m u-

formed im aginations, actions, and roles which in turn determined

that he who em bodied the active principle was greater than she who

sim ply waited — for sex, for gestation, for birthing w hich was not of

her doing and no t under her control.

Today we believe we have a completely different view. We have

learned that m ale and fem ale reproductive organs do n ot signal activity only for one and passivity for the other; n or do universalizable

m ale and fem ale character traits signal this. We can even appreciate all the ways in which, even at the physical level, m en's bodies

receive, encircle, em brace, and all the ways w om en's bodies are active, giving, penetrating. Today we also know that the possibilities

of m utuality ex ist for m any form s of relationsh ip— w hether heterosexual or gay w hether w ith genital sex or the multiple other ways

of embodying our desires and our loves. T h e key for us has become

not activity/passivity but active receptivity and receptive activity —

cach partner active, each one reccptivc. Activity and rcccptivity partake of one another, so that activity can be a response to som ething

received (like loveliness), and receptivity can be a kind of activity, as

in "rccciving" a guest.21

U nderlying the norm of m utuality is a view of sexual desire that

does not see i t as a search only for the pleasure to be found in the

relief of libidinal tension, although it may includc this. H um an sexuality, rather, because it is fundamentally relational, seeks ultim ately

21.

S e e G a b rie l M arcel, C rea tiv e Fidelity, tra n s. R obert R osen th a l |New York:

N oonday, 1 9 6 4 ), 8 9 - 9 1 .

tual trust.23 Insofar as we th ink th at sex is just and good only if

m utuality is p erfected , we know that personal incapacities large and

sm all can undercut it. We know that patience, as well as trust, and

perhaps unconditional love arc all needed for m utuality to become

what we dream it can be. But what is asked of us, demanded of us,

for the m utuality of a one night stand, or of a short-term affair, or of

a lifetim e of co m m itted love, differs in kind and degree.

Indeed, th e m utuality that makes sexual love and activity just

(and, one m u st add, that m akes for "good sex" in the colloquial sense

of the term) can be expressed in m any ways; and it does adm it of degrees. No m atter what, however, it entails som e degree of m utuality

in the attitudes and actions of both partners. It entails som e form

of activity and receptivity, giving and receiving — two sides of one

shared reality on the part of and w ithin both persons. It requires, to

som e degree, m utuality of desire, action, and response. Tw o liberties

m eet, two bodies m eet, two hearts com e together — metaphorical

and real descriptions of sexual mutuality. Part of each person's eth ical task, or the shared task in each relationship, is to determ ine the

2 2 . T h e c o n ce p t w as originally Sa rtr e's, alth ou gh h e used it to refer m o re to the

arousa l o f se x u a l attr a ctio n and d esire. S e e Jea n Paul Sa rtre , B ein g a n d N oth in g n ess,

tran s. H aze l E . B a rn e s (N ew York: P h ilo so p h ical Library, 1 9 6 6 ). For m o re con te m p o rary

u se s and ad ap tatio n s o f th is, see T h o m a s N ag el, "S e x u a l P e rv ersio n ," in P hilosophy

o f S ex: C o n te m p o r a r y R ea din gs , ed. A la n So ble (To tow a, N J: L ittlefield A d am s, 19 80 ),

7 6 - 8 8 ; So lo m o n , "S e xu a l P arad ig m s," ibid., 8 9 - 9 8 ; Ja n ice M o u lton , "S e x u a l B ehavior:

A n o th e r P o s itio n ," ibid ., 1 1 0 - 1 8 .

2 3 . For a d is cu ssio n of th is d anger in a w id er co n te x t, s e e R ich ard S e n n e tt,

"D e stru ctiv e G e m e in s c h a ft," ib id ., 2 9 9 - 3 2 1 .

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

TUST LOVE

threshold at w hich this norm m ust be rcspcctcd, and below w hich it

is violated.

the C h ristian com m unity's understanding of the placc of sexuality

in hum an and C hristian life has been the notion that som e form

4. Equality

of co m m itm en t, some form of covenant or at least contract, m ust

characterize relations that include a sexual dim ension. In the past,

this com m itm ent, of course, was largely identified with heterosexual

O ur considerations of m utuality lead to yet another norm th a t is

based on respect for relationality. Free choice and mutuality arc not

sufficient to respect persons in sexual relations. A condition for real

freedom and a necessary qualification of m utuality is equality. Th e

equality th at is a t stake here is equality of power. M ajor inequalities

in social and econom ic status, age and maturity, professional identity, interpretations of gender roles, and so forth, can render sexual

relations inappropriate and unethical prim arily bccausc they entail

power inequalities — and hence, unequal vulnerability, dependence,

and lim itatio n of options. T h e requirement of equality, like th e requirem ent of free consent, rules out treating a partner as property, a

commodity, o r an elem ent in m arket exchange. Jean-Paul Sartre describes, for example, a supposedly free and m utual exchange between

persons, but an exchange marked by unacknowledged domination

and subordination: "It is ju st that one of them preten ds. . . n ot to n otice th at th e O ther is forced by the constraint o f needs to sell himself

as a m aterial o bject."24

O f course here, too, equality need n ot be, m ay seldom be, perfect

equality. N onetheless, it has to be close enough, balanced enough,

for each to appreciate the uniqueness and difference of the other, and

for each to respect one another as ends in themselves. If the power

marriage. It was tied to the need for a procreative order and a discipline of unruly sexual desire. It was valued more for the sake of

fam ily arrangem ents than for the sake of the individuals themselves.

Even when it was valued in itself as a realization of the life of the

church in relation to Jesus C hrist, it carricd what today arc unwanted

connotations of inequality in relations between men and wom en. It

is possible, nonetheless, th at when all m eanings of com m itm en t in

sexual relations arc sifted, wc arc left with powerful reasons to retain

it as an ethical norm.

As we have already noted, contem porary understandings of sexuality point to different possibilities for sex than were seen in the p a st—

possibilities o f growth in the hum an person, personal garnering of

creative power with sexuality as a dim ension not an obstacle, and the

m ediation of hum an relationship. O n the other hand, no one argues

that sex n ecessarily leads to creative power in the individual or depth

of u nion betw een persons. Sexual desire left to itself does not seem

able even to sustain its own ardor. In the past, persons feared that

sexual desire would be too great; in the present, the rise of im potency

and sexual boredom m akes persons m ore likely to fear th at sexual desire will be too little.25 T h ere is growing cvidcnce that sex is neither

the indomitable drive th a t early C hristian s (and others) thought it

differential is too great, dependency will lim it freedom, and m utuality

will go awry. T h is norm , like the others, can illum inate the injury or

evil th at characterizes situations of sexual harassm ent, psychological

was nor the primordial im pulse of early psychoanalytic theory. W hen

it was culturally repressed, it seemed an inexhaustible power, under-

and physical abuse, at least som e form s of prostitution, and loss of

self in a process th at m ight have led to genuine love.

way or another. Now th a t it is less repressed, more and m ore free

5.

C o m m itm en t

Strong argum ents can be made for a fifth norm in sexual ethics,

also derivative of a responsibility for relationality. At the heart of

24.

Sa rtre, C ritiq u e o f D ia le c tica l R ea s o n , tran s. A . S h e rid a n -S m ith (Lond on: N LB,

1 9 7 6 ), 11 0 .

lying other m otivations, always struggling to express itself in one

25.

I a m n o t g ainsayin g F oucault’s critiq u e o f th e "repressive p rin cip le" here. In

fact, I m ay be re in fo rcin g it, sin c e so -calle d "rep re ssio n " m ay co n stru ct th e s o r t of

sex u a lity th a t is th e op p osite of w h a t rep ressio n a im s to do. M oreover, th e so rts of

w an in g se x u al d esire th at I d escribe fo r today m ay signal a d iffe ren t kind o f social

co n stru ctio n of se x u a l desire a n d se x u al p o ssibility : i t m ay be th e re su lt n o t o f too

m u ch sex bu t o f so cial and cu ltu ra l e m p h a sis o n org asm as th e sign o f accep table

and valued se x. O rg a s m ic an d o th e r e x p e cta tio n s o f sex ual perfo rm an ce m ay actu ally

un d ercu t th e po w er o f sex .

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

226

and in the open, it is easier to sec other com plex m otivations behind

O n the other hand, there is reason to believe that sexuality can be

the object of co m m itm ent, that sexual desire can be incorporated into

a covenanted love w ithout distortion or loss, but rather, w ith gain,

with en hancem ent. Given all the caution learned from contemporary

it, and to recognize its inability in and of itself to satisfy the affective

yearning of persons. M ore and more readily com es th e conclusion

drawn by m any th at sexual desire w ithout interpersonal love leads

to disappointm ent and a growing disillusionment. T h e other side of

this conclusion is th at sexuality is an expression o f som ething beyond itself. Its power is a power for union, and its desire is a desire

for intimacy.

O ne of th e central insights from contemporary ethical reflection

on sexuality is that norm s of justice cannot have as their whole goal

to set lim its to th e power and expression of hum an sexuality. Sexuality is of such im portance in hum an life that it needs to be nurtured,

sustained, as w ell as disciplined, channeled, controlled. Th ere appear

to be at least two ways w hich persons have found to keep alive the

power of sexual desire w ith in them . One is through novelty of persons with whom they are in sexual relation. Moving from one partner

to another prevents boredom, sustains sexual interest and the possibility of pleasure. A second way is through relationship extended

sufficiently through tim e to allow the incorporation of sexuality into

a shared life and an enduring love. T h e second way seem s possible

only through com m itm ent.

Both sobering evidence of the inability of persons to blend their

lives together, and weariness with the high rhetoric that has traditionally surrounded hum an covenants, yield a contemporary reluctance

to evaluate th e two ways of sustaining sexual desire and living sexual

union. At th e very least it may be said, however, that although brief

encounters open a lover to relation, they cannot m ediate the kind of

union — of knowing and being known, loving and being loved — for

w hich hum an relationality offers the potential. Moreover, the pursuit of m ultiple relations precisely for the sake of sustaining sexual

desire risks violating the norm s of free consent and mutuality, risks

m easuring oth ers as apt m eans to our own ends, and risks inner disconnection from any kind of life-process of our own or in relation

w ith others. D iscrete m om ents of union are n o t valueless (though

they may be so, and m ay even be disvalucs), but they can serve to

isolate us from others and from ourselves.

TUST LOVE

experience, w e may still hope that our freedom is sufficiently powerful to gather up our love and give it a future; that thereby our sexual

desire can be nurtured into a tenderness that has no t forgotten passion. We m ay still believe th at to try to use our freedom in this way

is to be faithful to the love that arises in us or even the yearning that

rises from us. R hetoric should be lim ited regarding com m itm ent,

however, for particular forms of com m itm ent are them selves only

m eans, n ot ends. As Robin M organ notes regarding the possibility of

process only w ith an enduring relation, "C om m itm en t gives you the

leverage to bring about change — and the tim e in which to do it."26

A C hristian sexual ethic, then, m ay well identify com m itm en t as

a norm for sexual relations and activity. Even if com m itm ent is only

required in th e form of a com m itm en t not to harm one's partner, and

a co m m itm ent to free consent, mutuality, and equality (as I have described these above), it is reasonable and necessary. M ore than this,

however, is necessary if our concerns are for the wholeness of the

hum an person — for a way of living th at is conducive to th e integration of all of life's im portant aspects, and for the fulfillm ent of sexual

desire in the highest form s of friendship. Given these concerns, the

norm m ust be a com m itted love.

6. Fruitfulness

A sixth norm derivative from the obligating feature of relationality is

what I call "fruitfulness." Although the traditional procreative norm

of sexual relations and activity no longer holds absolute sway in

C hristian sexual ethics in either Protestant or Rom an C atholic traditions, there rem ains a special concern for responsible reproduction of

the hum an species. Traditional arguments th at if there is sex it m ust

26.

R ob in M o rg an , "A M arriag e M a p ," Ms. M a ga zin e 11 (Ju ly-A u g ust 1 9 8 2 ): 2 0 4 .

For fu rth e r elab o ratio n o n th e m ean in g o f interp e rso n al co m m itm e n ts, s e c Farley, Pers o n a l C o m m itm e n t s . In th is boo k , th ere arc w ay s o f d e scribing c o m m itm e n t itse lf th at

co u ld allow it t o b e th o u g h t of a s a t le a st part of an end — for e xa m p le th e en d o f love

and friendship. I t h as o r ca n have in trin sic v alu e in th a t it is c o n stitu te d by th e one

givin g to th e o th e r h e r "w o rd ," w ith a n e w fo rm of relatio n sh ip now established.

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

228

be procrcativc have changed to arguments that if sex is procrcativc it

m ust be w ith in a context that assures responsible care of offspring.

T h e connection between sex and reproduction is a powerful one, for

it allows individuals to reproduce and to build families; it allows a

who love. T h e new life w ithin the relationship of those who share it

m ay move beyond itself in countless ways: nourishing other relationships; providing goods, services, and beauty for others; inform ing the

fruitful work lives of the partners in relation; helping to raise other

sharing of life full enough to issue in new lives; and it allows the

hum an spccics to perpetuate itself. Relationality in the form of sexual reproduction, moreover, does n ot end w ith the birth of children,·

it stretches to include th e rearing of children, th e in itiation of new

people's children; and on and on. All o f these ways and m ore may

constitute the fruit of a love for w hich persons in relation arc responsible. A ju st love requires the recognition of this as the potentiality

of lovers; and it affirms it, each for the other, both together in the

generations in to a culture and civilization, and th e ongoing building

fecundity of their love. Interpersonal love, then, and perhaps in a

special way, sexual love insofar as it is just, m ust b e fruitful.

T h e articulation of this norm , however, moves us to another perspective in the development of a sexual ethic. T h ere are obligations

in justice th at the wider com m unity owes to those who choose sexual

relationships. Hence, our final norm is of a different kind.

of th e h um an community.

At first glance, it appears that "procreation" belongs only to, is

only possible for, som e persons; and even for them , it has com e to

seem quite optional. How, then, can it constitu te a norm for sexual

activity and relations? Even if it were recognized as a norm for fertile

TUST LOVE

heterosexual couples, what would th is m ean for infertile heterosexual

couples or for heterosexual couples who choose not to have children,

for gays and lesbians, for single persons, for ambiguously gendered

persons? For these other individuals and partners, would it signal,

as it has in the past, a lesser form of sex and lesser form s of sexual

T h is norm derives from our obligation to respect relationality, but

n ot o nly from this. It derives more generally from the obligation to

respect all persons as ends in themselves, to respect th eir autonomy

relationships? Or is it possible that a norm of fruitfulness can and

ought to characterize all sexual relationships?

It is ccrtainly true th at all persons can participate in the rearing

of new generations; and some o f those w ho cannot reproduce in traditional ways do even have their own biological children by means

and relationality, and thus not to harm them but to support them . A

social justice norm in the context of sexual eth ics relates no t specifically to the ju stice betw een sexual partners. It points to the kind of

justice th at everyone in a com m unity or society is obligated to affirm for its m em bers as sexual beings. W hether persons are single

of th e growing array of reproductive technologies — from infertility

treatm ents to artificial insem ination to in vitro fertilization to surrogate m othering. All of this is not only true but significant. Yet an

ethically norm ative claim on sexual partners to reproduce in any of

or married, gay or straight, bisexual or ambiguously gendered, old or

young, abled or challenged in the ordinär)' forms of sexual expression, they have claim s to respect from the C hristian com m unity as

well as th e wider society. Th ese are claim s to freedom from unjust

these ways seem s unwarranted.

harm , equal protection under th e law, an equitable share in the goods

Som ething m ore is at stake. Beyond the kind of fruitfulness that

brings forth biological children, there is a kind of fruitfulness that is

a measure, perhaps, of all interpersonal love. Love between persons

violates relationality if it closes in upon itself and refuses to open to

a wider co m m unity o f persons. W ithout fruitfulness of som e kind,

and services available to others, and freedom of choice in their sexual lives — w ithin the lim its of no t harm ing or infringing on the

ju st claim s of the concrete realities of others. W hatever the sexual

status of persons, their needs for incorporation into the community,

for psychic security and basic well-being, m ake the sam e claim s for

social cooperation am ong us as do those o f us all. T h is is why I call

any significant interpersonal love (not only sexual love) becom es an

ég oism e à deux. If it is completely sterile in every way, it threatens

the love and the relationship itself. But love brings new life to those

7. S ocia l Ju s tice

the final norm "social ju stice." If our loves for one another are to be

just, then this norm obligates us all.

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

TUST LOVE

T h ere is o ne way in which, of coursc, this norm qualifies sexual

relationships themselves, obligating sexual partners as well as the

bias would b e high on the list of the issues I have in m ind.31 Th e

m yths and doctrines of religious and cultural traditions th at reinforce

com m unity around them. T h a t is, sexual partners have always to

be concerned about n ot harm ing "third parties." As Annette Baier

observes, "in love there are always third parties, future lovers, ch il-

gender bias and u njust constriction of gender roles becom e im portant

here as w ell.32 Included, too, m ust be the disproportionate burden

that w om en bear in the world-wide A ID S pandem ic.33

We have already seen in the previous chapter the kinds of injustices

dren who m ay be born to one of the lovers, their lovers and their

children."27 A t th e very least, a form of "so cial ju stice" requires of

sexual partners th at they take responsibility for the consequences of

their love and their sexual activity — w hether the consequences are

pregnancy and children, violation o f the claim s that others may have

on each of them , public health concerns, and so forth. No love, or at

least no great love, is just for "th e two of u s,"28 so th at even failure

to share in som e way beyond the two of us the fruits of love m ay be

a failure in justice.

My focus in articulating th is norm, however, is primarily on the

larger social world in w hich sexual relationships arc formed and sustained. It includes, therefore, the sorts of concerns I identified above,

but larger concerns as well. A case in point is the struggle for gender

equality and (in particular) w om en's rights in our own society and

around th e world. T h is is relevant to the sexual eth ic I am proposing

because it h as a great deal to do w ith respect for gender and sexuality

as it is lived in concrete contexts of sexual and gender injustice.

Here we could identify numerous oth er issues of utm ost importance. Sexual and dom estic violence m ight head the list, both at

inflicted on persons whose gender and sexuality do not fall into the

usual categories. We should add issues surrounding the explosion

of reproductive technologies — many of which have proven to offer a

great benefit for individuals, but m any of w hich rem ain questionable,

such as technologies for sex-selection.34 Other issues also require

m oral assessm ent, such as the availability (or not) of contraceptives,

and the repercussions for som e w omen of the m arketing of male

remedies for im potence. It is neither possible nor necessary to detail

all of these issues here. M y point is only that they, too, fall within

the concerns of an adequate hum an and C hristian sexual ethic. T hey

signal social and com m unal obligations not to harm one another

unjustly and to support one another in what is necessary for basic

well-being and a reasonable level of hum an flourishing for all. T hese

obligations stretch to a com m on good — one that encompasses the

sexual sphere along with the other significant spheres of hum an life.

In sum mary, w hat I have tried to offer here is a framework for sexual ethics based on norms of justice — those norm s which govern all

hom e and abroad.29 But it would include also racial violence that is

perpetrated on m en and w om en and th at all too often has to do with

false sexual stereotypes.30 Development, globalization, and gender

3 1 . Se e, for e x am p le: N u ssb au m , S e x a n d S o c ia l Ju stice·, N u ssba u m and Glover,

W om en , C u ltu re, a n d H u m a n D e v e lo p m e n t ; A m artya S e n , "O v er 1 0 0 M illio n W om en

A re M iss in g ," N e w York R e v ie w o f B o o k s (D e cem be r 2 0 , 1 9 9 0 ): 6 1 - 6 6 .

2 7 . A n n e tte C . Baier, M oral P r eju d ice s: E ssay s o n E th ics (Ca m brid g e, M A : Harvard

U n iv e r sity P re ss, 1 9 9 4 ), 147.

2 8 . M a ry M c D e r m o tt Shid eler, T h e T h e o lo g y o f R o m a n tic L o v e : A Stu d y in th e

Writings o f C h a r le s W illiam s (G ra nd R apid s, M I: E erd m a n s, 1 9 6 2 ), 1 1 5 .

2 9 . T h e m a n y w ritin gs o f M arie F ortun e provide d escriptive a n d n o rm a tiv e analy ses

of th e se issu e s. S e e e sp ecia lly th e new v ersion o f h e r e arliest w o rk o n se xual vio len ce

a s " t h e u n m en tio n a b le s in ," in M a rie M a rsh a ll Fortu ne, S ex u a l V io len c e : T h e Sin R ev is ite d (C le ve la n d : P ilgrim , 2 0 0 5 ). For co n sid era tio n s o f the se issu e s in te rn atio nally,

sec M ary Jo h n M a n a n za n e t al., ed s., W om en R esistin g V iolen c e: S p iritu ality fo r Life

(M a ry kn oll, NY: O rb is, 1 9 9 6 ).

3 0 . Se e, for e x a m p le, th e d iverse e ssay s in E m ilie M . T ow n es, e d ., A T ro ubling in

m y S o u l (M a ry k n o ll, NY: O rb is, 1 9 9 3 ).

C a lifo r n ia P r e ss , 1 9 9 5 ).

3 2 . T h e r e a re co u n tless w orks by th eo log ians o n th e se issu es now , b u t se c, in particular, H ow ard E ilb erg-S ch w artz an d W endy D onige r, e d s., O ff w ith H er H e a d ! T h e

D e n ia l o f W o m e n ’s Id e n tity i n M yth, R eligion , a n d C u ltu re (Berkeley: U n iv ersity of

3 3 . S e e Farley, C o m p a s s io n a t e R e s p e c t, 3 - 2 0 ; s e c also L in d a Singer, "R eg u latin g

W o m en in th e A ge o f S ex u al E p id e m ic," in E rotic W elfare: S e x u a l T h e o r y a n d Politics

in th e A ge o f t h e E p id e m ic , ed. Ju d ith B u tle r and M au re en M acG rogan (New York:

R outledge, 1 99 3 ).

3 4 . S e e C o m m itt e e o n E th ic s, " S e x S e le ctio n " (W ashington, D C : A m e rican C o llege o f O b s te tric ia n s and G y n e co lo g ists, N o v e m be r 1 9 9 6 ). Fo r a care fu l probing of

rep roductive te ch n o lo g ies m o re generally, se c M au ra A. R yan, E thics a n d E con o m ic s

o f A ssis ted R ep r od u c tio n : T h e C ost o f L on gin g (W ashington, D C : G e org etow n U n ive rsity P re ss, 2 0 0 1 ). S e e also Lisa So w ie C a h ill, " T h e N e w B irth T ech n o lo gie s and Pu blic

M o ra l A rg u m e n t," in C a h ill, Sex, G e n d e r a n d C h ristia n E thics (C am b rid ge : C am brid ge

U n iv e rsity P re ss , 1 9 9 6 ), 2 1 7 - 5 4 .

Fram ew ork fo r a Sexual Ethic: fust Sex

TUST LOVE

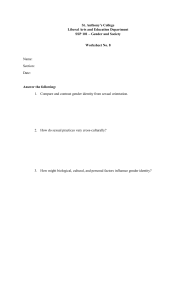

Norms for Sexual Justice

B a s is

N o rm

R e s p e c t f o r t h e a u t o n o m y a n d r e la tio n a li t y

t h a t c h a r a c t e r i z e p e r s o n s a s e n d s in th e m s e l v e s ,

a n d h e n c e r e s p e c t f o r t h e i r w e ll- b e in g :

1 . D o n o u n ju s t h a r m

R e sp ect fo r a u to n o m y :

2 . F re e c o n s e n t o f p a r t n e r s

R e s p e c t f o r r e la tio n a lit y :

3 . M u t u a l it y

4 . E q u a lity

5 . C o m m itm e n t

6 . F r u itf u ln e s s

R e s p e c t f o r p e r s o n s a s s e x u a l b e in g s i n s o c ie t y :

7 . S o c ia l ju s t ic e

hum an relationships and those w hich are particular to the intimacy

of sexual relations. M ost generally, th e norm s derive from the concrete reality o f persons and are focused on respect for their autonomy

and relationality. T h is is to respect persons as ends in them selves. It

yields an in ju nctio n to do no unjust harm to persons. It also yields

spécifications both of w hat it m eans to respect autonomy and relational! ty and what it m eans to do n o harm . Autonom y is to be

respected through a requirem ent of free consent from sexual partners, w ith related requirem ents for truthtclling, promise-keeping,

and respect for privacy. Relationality is to be respected through requirem ents o f mutuality, equality, com m itm ent, fruitfulness, and

social justice.

Even m ore specifically, we m ay in term s of this framework say

things like: sex should not be used in ways th a t exploit, objectify, or

dom inate; rape, violence, and harmful uses of power in sexual relationships arc ruled out; freedom, wholeness, intim acy, pleasure arc

values to be affirmed in relationships marked by mutuality, equality,

and som e form of com m itm ent; sexual relations like other profound

interpersonal relations can and ought to be fruitful both w ithin and

beyond th e relationship; the affections of desire and love that bring

about and sustain sexual relationships are all in all genuinely to

affirm both lover and beloved.

I rccognizc full well that it is not an easy task to introduce co nsiderations o f justice into every sexual relation and the evaluation of

every sexual activity C ritical questions rem ain unanswered, and serious disagreem ents are all too frequent, regarding the concrete reality

of persons and th e m eanings of sexuality. W hat can be norm ative

and w h at exceptional — th at is, what is governed by the norm s I have

identified and w hat can be exceptions to these norm s — is sometim es

a m atter of all too delicate judgment. But if sexuality is to be creative

and not destructive in personal and social relationships, then there is

no substitute for discerning ever m ore carefully the norm s whereby

it will be just.

Sp ecial Q uestions

I hope th at w hat I have delineated above as a justice ethic for the

sphere of sexuality in hum an life already speaks of the practice of this

ethic. It is n o t intended to be merely an abstract outline of ethical

principles and rules. T h e chapter that follows will attem pt to show

w hat this e th ic m eans in response to particular aspects of our lives.

T h ere are further questions th at bear consideration, however, before I

leave the substance of th is chapter. Som e of these questions challenge

the ethic I have proposed; som e of th em expand it in ways that may

be particularly im portant to the C hristian com m unity

A n Ethic O nly fo r Adults*

Insofar as a justice ethic m akes sense at all, can it m ake any difference to teenagers whose reported sexual practices today appear

untouchable by traditional or new ethical frameworks? I am not here

referring to th e exploitation of the young by adults in th e multiple

form s that sexual harm is perpetrated. T h e ethical norm s I have

outlined are clearly intended to protect the young in special ways

from the violence and m anipulation of adults who would use the

vulnerable sexuality of children and adolescents for their own (that

is, the adults1') pleasure or m onetary gain. I am , rather, referring to

the practices o f teenagers am ong themselves. M y focus is, of course,

on practices th at arc no doubt time-bound and culture-bound, but I

Fram ew ork for a Sexual Ethic: Just Sex

suspcct there are analogues th at will emerge again and again, at least

in W estern culture.

T h e phenom enon of "hooking up" is an example of a practice

among teenagers that seem s to elude any norm s other than acceptance am ong peers.33 "H ooking up" is precisely w hat it depicts:

sex w ithout any relationship and w ithout any strings. "Friends with

benefits" differs in th at there is som e form of friendship prior to

sexual activity, but still, no strings. D ating still exists, but at least

according to som e reports, appears not to be the sexual relationship

of choice. "W e might date— I don't know. It's just that guys can get

so annoying w hen you start dating th em ."36 "Now that it's easy to get

sex outside o f relationships, guys don't need relationships."37 Many

teenagers, according to these reports, are looking for anything but

com m itm ent — or even m utuality in any sense other than physical.

T h ere m ay be a growing concern am ong teen-agers for "safe sex,"

in the sense o f protection especially against sexually transm itted diseases. W hether or n ot this fuels the reported wide-spread practice of

oral sex is hard to determine. W h at is clcar, however, is th at adolescents are m isinform ed about the health consequences of oral sex

and other sexual practices, so th at it is hard to believe th a t "concrete

realities" of persons arc m uch taken into account. If a justice cth ic is

to make any difference at all in the choices th at young people make

regarding their sexuality, the first step will have to be education about

sex and its dangers as well as sexuality and the ways it may be not

only harm less but good.

TUST LOVE

that they represent some. W hat can a justice eth ic say to these particular practices and experiences? W hat can it say to adolescents for

whom these practiccs arc not part of their experience? W hat have wc

to offer young girls who, in th e m idst of this kind of sexual activity, or on the outside looking in, say that they do this or want this

because their lives are boring? O r because they want relationships,

though they seek them in vain in the practices that aim to make relationships unnecessary? And what can we say to young boys, who

appear to enjoy these practices more th an girls; who find in them a

way to stay uncom m itted yet have access to sexual partners alm ost

w ithout lim it?38

I do no t here, as I have said, attem pt to assess how widespread

these practices may be. Nor do I attem pt to judge the practices th em selves — at least n ot w ithout longer term em pirical studies of the

consequences and n ot w ithout a careful consideration of the to tal situation in w hich W estern teenagers find themselves today. I do w ant

to raise the m odest but urgent question: Suppose these practices are

harm ful to young people. Suppose some of them enjoy these practices, but som e do not. Suppose som e of them feel used, but their

partners have no understanding of this. Would sexual taboo morality

change the situation? Perhaps so, perhaps not, but its lasting effect

m ight have to do with developing sham e and guilt more than wisdom

and prudence about hum an sexuality.39

W hether o r not published reports about the sexual lives of teenagers and even of pre-teen children actually reflect the m ajority of

teenage experiences (and I do no t assume that they do), it is clear

3 8 . F o r so m e in sig h ts in to the se e x p erie nces, se e Blodgett, C on str u ctin g th e E ro tic,

e sp ecially ch a p te r s 4 - 5 .

3 9 . In 1 9 9 4 t h e Se x u ality In fo rm a tio n and E d ucation C o u n c il o f t h e U n ited States

(SIE C U S1 co n v en ed th e N a tio n al C o m m issio n o n A d o lesce n t Sexu al H e a lth . T h is

C o m m issio n developed a co n se n su s s ta te m e n t th a t high lighted th e need fo r ad ults

3 5 . Se e, for e x am p le, B e n o it D en iz et-L ew is, "Friend s, F riend s w ith B e n e fits, and

th e B en e fits o f th e L oca l M a ll/ ’ N e w York T im e s M a g az in e {M ay 3 0 , 2 0 0 4 ) : 3 0 - 3 5 ,