Justin J. Lehmiller - The Psychology of Human Sexuality-Wiley (2017) (1)

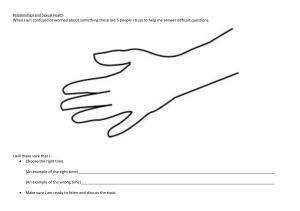

advertisement