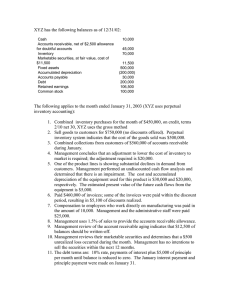

Mary the Queen College (Pampanga), Inc. Jasa, San Matias, Guagua, Pampanga Online Module Format Institute/Department Subject Code: FinMgt Module No./title: Module 4 : Management of Current Assets Subject Description: Financial Management Period of coverage: Week 6-7 Introduction : This learning material discusses the different techniques in managing current assets such as cash, marketable securities, receivables and inventories. You will be able to achieve the desired learning outcomes by devoting time and effort in studying this material, listening and participating actively in the online discussion, and accomplishing the tasks assigned in the Classwork section of the Google Classroom for this course. Learning objectives : After studying this module, you should be able to understand : 1. Cash and Marketable Securities Management 2. Accounts Receivable and Inventory Management Content : LESSON 1 : MANAGING CASH AND MARKETABLE SECURITIES Cash Management involves the control over the receipts and payments of cash to minimize nonearning cash balances. OBJECTIVE OF CASH MANAGEMENT The basic objective of cash management is to keep the investment in cash as low as possible while keeping the firm operating efficiently and effectively. A financial officer can use the following strategies in monitoring cash balances: 1. Accelerate cash inflows by optimizing mechanisms for collecting cash 2. Monitor the cash disbursement needs or payments schedule 3. Minimize the amount of idle cash or funds committed to transaction and precautionary balances 4. Avoid misappropriation and handling losses in the normal course of business. Proper management of cash flows entails the following. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Improving forecast of cash flows Using floats Synchronizing cash inflows and outflows Accelerating collection Controlling disbursements Obtain additional funds when and where they are needed. REASONS FOR HOLDING CASH BALANCES A business enterprise may keep cash due to following reasons. 1. 2. 3. 4. Transaction Facilitation Precautionary Motive Compliance with Creditor’s Covenant (compensating balance) Investment Opportunities Company must know how the trade-off between the opportunity costs associated with holding too much cash against the shortage costs of not having enough cash. DETERMINING THE TARGET CASH BALANCE Cash Budget The cash budget is the tool used to present the expected cash inflows and cash outflows. Cash Break-even Chart This chart shows the relationship between the company’s cash needs and cash sources. It indicates the minimum amount of cash that should be maintained to enable the company to meet its obligations. Illustration: XYZ Company manufactures plastic which it sells to other industrial users. The monthly production capacity of the company is 1,200,000 kilos. Selling price is P2 per kilo. Its cash requirements have been determined as follows: a.) Fixed monthly payments amounting to P250,000 b.) Variable cash payments are 50% of sales. Required: 1. Determine the cash breakeven point. Solution: 1. Cash Break-even Point = / , = = % % % , % = P500,000 or 250,000 kilos of plastic OPTIMAL CASH BALANCE The Baumol Model Liquidity management has assumed a greater role over the past decade since cash is needed for both transactions and precautionary needs in all companies. The liquidity managers must utilize some formal models or techniques to maintain the optimal amount at each moment in time because too much liquidity brings down the rate of return on total assets employed and too little liquidity jeopardizes the very existence of the firm itself. In managing the level of cash (currency plus demand deposits) for transaction purposes versus near cash (marketable securities), the following cost must be considered: 1. Fixed and variable brokerage fees 2. Opportunity costs such as interest forgone by holding cash instead of near cash. One of the models that can be used to help determine the optimal cash balance is the “Baumol model”. This model balances the opportunity cost of holding cash against the transactions costs associated with the replenishing the cash account by selling off marketable securities or borrowing. The optimal cash balance can be found in the following variables and equations” 1. The total costs of cash balances consist of holding (or opportunity cost plus transaction cost: Total Costs = Holding costs + Transaction costs = (Average Cash Balance)(Opportunity Costs) + (No. of transactions)(Cost per Transaction) = ( )+ ( ) Where: C = amount of cash raised by selling marketable securities or by borrowing C/2 = average cash balance C* = optimal amount of cash to be raised by selling marketable securities or by borrowing C*/2 = optimal average cash balance F = fixed costs of making a securities trade or of obtaining a loan T = total amount of net new cash needed for transactions during the period (usually a year) K = opportunity cost of holding cash, net equal to the rate of return foregone on marketable securities or the cost of the borrowing to hold cash. 2. The minimum costs of cash balances are achieved when C is set equal to C*, the optimal cash transfer or optimal cash replenishment level. The formula to find C* is as follows: C* = C* = ( )( ( )( ) Illustrative Case I: Determination of Optimal Average Cash Balance for Baumol Model To illustrate, consider a business with total payments of P10 million for one year, cost per transaction of P100, and the interest rate on marketable securities is 8 percent. The optimal cash balance is calculated as follows: C* = ( )( ) % = P158,114 Optimal average cash balance = , = P79,057 The firm may also want to hold a safety stock of cash to reduce the probability of a cash shortage to some specified level. The Baumol model is simple in many respects. The Miller-Orr Model The Miller-Orr model takes a different approach to calculating the optimal cash management strategy. It assumes that the distribution of daily net cash flows is normally distributed and allows for both cash inflows and outflows. This model bases its computations where: L F Ó I day Z* H* = the lower control limit = the trading cost for marketable securities per transaction = the standard deviation in net daily cash flows = the daily interest rate on marketable securities = optimal cash return point = upper control limit for cash balances To compute Z*, the following formula is applied Ó Z* = + To compute for H*, the following formula is used: H* = 3Z* - 2L Illustrative Case II: Calculation of Optimal Return Point and Upper Limit for Miller-Orr Model Suppose that ABC Inc., would like to maintain its cash account at a minimum level of P100,000, but expects the standard deviation in net daily cash flows to be P5,000; the effective annual rate on marketable securities will be 8 percent per year, and the trading cost per sale or purchase of marketable securities will be P200 per transaction. What will be ABC’s optimal cash return point and upper limit? Solution: The daily interest rate on marketable securities will equal to: % I day = Z* = ( )( . = P126,101.72 = .00021 ) + 100,000 H* = 3(126,101.72) – 2(100,000) = 378,305.16 – 200,000 = P178,305.16 As shown in the above computation, the firm will reduce cash to P126,101.72 by buying marketable securities when the cash balance gets up to P178,305.16, and it will increase cash to P126,101.72 by selling marketable securities when the cash balance gets down to P100,000. CASH MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES Effective cash management encompasses the proper management of cash inflows and outflows, which involve: 1. Synchronizing Cash Flows Synchronize cash flows is a situation in which inflows coincide with outflows thereby permitting a firm to hold low transactions balances. A thorough review of the cash flow analysis, cash conversion cycle and cash budget would be most helpful. 2. Using Floats Floats is defined as the difference between the balance shown in a firm’s books and the balance on the banks record. It arises from the delays in mailing, processing and clearing checks through banking system. Disbursement Float represents the value of the checks the firm has written but which are still being processed and thus have not been deducted on the firm’s account balance by the bank. For example, suppose a firm writes on the average, checks amounting to P50,000 each day, and it takes 5 days for these checks to clear and to be deducted from the firm’s bank account. This will cause the firm’s own checkbook to show a balance of P250,000 smaller than the balance on the bank’s records. Collections float represents the amount of checks that have been received but which have not yet been credited to the firm’s account by the bank. Suppose that the firm also receives checks in the amount of P50,000 but it loses four days while they are being deposited and cleared. This will result in P200,000 of collections float. In total, the firm’s net float, the difference between P250,000 positive disbursement float and the P200,000 negative collection float, will be P50,000. If the net float is positive, that is, disbursement float is more than collection float, then the available bank balance exceeds the book balance. A firm with a positive net float can use it to its advantage and maintain a smaller cash balance than it would have in the absence of the float. 3. Accelerating Cash Collections The finance manager should take steps for speedy recovery from debtors and for this purpose, proper internal control should be installed in the firm. Once the credit sales have been effected there should be a built-in mechanism for timely recovery from the debtors such as: a. b. c. d. e. f. Prompt billing and periodic statements Incentives such as trade and cash discounts Prompt deposit Direct deposit to firm’s bank account Electronic depository transfer or payment by wire Maintenance of regional collection office The above techniques can minimize the time lag between the time the customers send the checks to the firm and the time when the firm can make use of the funds. This system of cash collection will accelerate the cash inflows of the firm. 4. Slowing Disbursements Any action on the part of the finance officer which slows the disbursement of funds lessens the use for cash balance. This can be done by: a. b. c. d. e. Centralized processing of payables Zero balance accounts (ZBA) Delaying payment Play the float Less frequent payroll 5. Reducing the Need for Precautionary Balance Since the transaction and precautionary motives are the important determinants of the cash requirement, factors influencing their combined level in the firm must be analyzed. There are techniques that are available for reducing the need for precautionary balances. These include: a. More accurate cash budgeting b. Lines of credit c. Temporary investments LESSON 2: MANAGING MARKETABLE SECURITIES Objective of Marketable Securities Management Management of cash and marketable securities cannot be separated, as management of one implies management of the other. Reasons for Holding Marketable Securities 1. They serve as a substitute for cash balances. 2. They are held as a temporary investment. 3. They are built up to meet known financial requirements. Factors Influencing the Choice of Marketable Securities 1. Risks such as a. Default risk. The risk that the issuer of the security can not pay the principal or interest at due dates. The funds invested in short-term marketable instruments should be safe and secure as regards repayment of principal and interest as and when it matures since the return on short-term investments is offered less than long-term investments, the acceptable risk level is required to be lesser commensurate with lower return. Some of the investments like commercial paper are offered with credit ratings. The government treasury bills, banker’s acceptance and certificate of deposits carry minimum default risk. b. Interest rate risk. The risk of declines in market values of the security due to rising interest rates. c. Inflation risk. The risk that inflation will reduce the “real” value of the investment. In periods of rising prices, inflation risk is lower on investments (e.g., common stock, real estate) whose returns tend to rise with inflation than on investment whose returns are fixed. d. Marketability (liquidity) risk. This refers to the risk that securities cannot be sold at close to the quoted market price and is closely associated with liquidity risk. The liquidity is the basic objective of investment in these instruments. It should offer the facility of quick sale in the market as and when need arises for cash, with low transaction cost, without loss of time and no erosion of amounts invested with fall in price of investments. e. Event risk. The probability that some event (such as merger, recapitalization or a leverage buyout) will occur and suddenly will increase a firm’s default risk. Bonds issued by regulated companies as banks or electric utilities generally have lesser event risk that bonds issued by industrial and service companies. Treasury securities usually do not carry any risk, barring national disaster. Also, long-term securities are affected more by unfavorable events than are short-term securities. 2. Maturity. Marketable securities held should mature or can be sold at the same time cash is required. Firms generally invest in marketable securities that have relatively short maturities. The maturity periods of different investments should match with the payment obligations like dividend payments, tax payments, capital expenditure and interest payments on debt instruments. Many firms restrict their temporary investments to those maturing in less than 90 days. Short-term investments relatively carry lesser return than long-term investments, since the default risk and interest rate risk are minimized with short-term instruments. 3. Yield or returns on securities. Generally, the higher a security’s risk, the higher its required return. Corporate investors, like other investors must make a trade-off between risk and return when choosing marketable securities. Because these securities are generally held either for a specific known need or for use in emergencies, the portfolio should consist of highly liquid short-term securities issued by the government or very strong corporations. Treasures should not sacrifice safety for higher rates of return. Types of Marketable Securities 1. Money Market Instruments. These are the most suitable investment for idle funds. The money market is the market for short-term debt instruments. Money market instruments are highgrade securities characterized by a high-degree of safety of principal and maturity of one year or less. The two major types of money market instruments are a) Discount Paper. A money market instrument which sells for less than its par or face value. The difference between the security’s purchase price and par value represents the investor’s income. At maturity, the investor receives the face value or par value of the instrument. b) Interest-bearing securities. These are instruments which pay interest based on the par value or face value of the security and the period (days/months) of investment. 2. Treasury Bills. These are short-term government securities with a maturity of one year or less, issued at a discount from face value often called risk-free security. These securities are tax exempt with high degree of marketability. 3. Other Short-term Commercial Papers Issued by Finance Companies, Banks and Other Corporations. These are typically unsecured and maturities range from a few days to 270 days. Commercial paper is usually discounted by it can be interest bearing. 4. Negotiable Certificates of Deposit. Certificate of deposits are short-term loans to commercial banks with maturities ranging from a few weeks to several years. Certificate of deposits contain some default and interest rate risks but can easily be sold prior to maturity. 5. Repurchase Agreements (REPOS). These are sale of government securities (e.g., treasury bills) or other securities by a bank or securities dealer with an agreement to repurchase. REPOS usually involve a very short-term overnight to a few days. These are attractive to corporations because of the flexibility or maturities. These agreements have little risk because of their short maturity and the commitment of the borrower to repurchase the securities as a fixed or higher specified price. 6. Banker’s Acceptance. A time draft drawn on, and accepted by a bank usually used as a source of financing in international trade. Banker’s acceptances are sold as discount paper with maturities ranging from a few weeks to 9 months. The yields on acceptance are competitive because of low default risk owing to as many as three parties who may be liable for payment at maturity. 7. Money Market Mutual Fund. This is an open-ended mutual fund that invests in money-market instruments. Money market mutual funds (MMMF) sell shares to investors and then accumulate the funds to acquire money market instruments. These funds allow small investors to participate directly in high-yielding securities that are often denominated in large amounts. The MMMF shares are highly liquid because they can be sold bank to the fund any time. Returns or yields depend on the money market instruments held in the portfolio of the fund. LESSON 3: MANAGING RECEIVABLES Objective of Accounts Receivable Management The goal of accounts receivable management is to ensure that the firm’s investment in accounts receivable is appropriate and contributes to shareholder wealth maximization. It is therefore the responsibility of the finance officer to evaluate the pertinent costs and benefits related to credit extension, to finance the firm’s investment in accounts receivable, implement the firm’s credit policy and to enforce collection. CREDIT POLICY Credit policy is a set of guidelines for extending credit to customers. The success or failure of a business depends primarily on the demand for its products – as a rule, the higher its sales, the larger its profits and the higher the value of its stock. Sales, in turn, depend on several factors, some exogenous but under the control of the firm. The major controllable variables which affect the demand are sales prices, product quality, advertising and the firm’s credit policy. Credit policy generally covers the following variables: 1. Credit Standards Credit standards refer to the minimum financial strength of acceptable credit customer and the amount available to different customer. Credit policy can have a significant influence upon sales. If the credit policy is relaxed, while sales may increase, the quality of accounts receivable may suffer. To measure the credit quality and customer’s credit worthiness, the following areas are generally evaluated. · Character · Capacity · Capital · Collateral · Conditions 2. Credit Terms Credit terms involve both the length of the credit period and the discount given. Credit period is the length of time buyers are given to pay their purchases. Discounts are price reductions for early payment. The discount specifies what the percentage reduction is and when the payment must be to be eligible for the discount. 3. Collection Policy Collection policy refers to the procedures the firm follows to collect past-due accounts. For example, a letter may be sent to customers when bill is 10 days past due; a more severe letter, followed by a telephone call, may be used if payment is not received within 30 days; and the account may be turned over to collection agency after 90 days. 4. Delinquency and Default Whatever credit policies a business firm may adopt, there will be some customers who will delay and others who will default entirely, thereby increasing the total accounts receivable costs. Summary of Trade-offs in Credit and Collection Policies Trade-offs 1. Relaxation of credit standards Benefit/s a. Increase in sales and total contribution margin 2. Lengthening credit period of a. Increase in sales and total contribution margin cash a. Increase in sales and total contribution margin b. Opportunity income on lower investment in receivable a. Lower default costs (bad debts) b. Lower opportunity cost or capital costs 3. Granting discount 4. Intensified collection efforts Cost/s a. Increase in credit processing costs. b. Increase in collection costs c. Higher default costs (bad debts) d. Higher capital costs (opportunity costs) a. Higher capital costs (opportunity cost of higher investment in receivables) a. Lesser profit a. Higher collection expenses b. Lower sales. Marginal or Incremental Analysis of Credit Policies Marginal Analysis is performed in terms of a systematic comparison of the incremental returns incremental returns and the incremental costs resulting from a change in the firm’s credit policy. Whenever the incremental profit from a proposed change in the management of accounts receivable exceeds the required return or incremental costs of the additional investment, the change should be implemented. Illustrative Case I: Relaxation of Credit Policy ABC Corporation’s products sells for P10 a unit of which P7 represents variable costs before taxes including credit department cost. Current annual credit sales are P2.4 million. The firm is considering a more liberal extension of credit, which will result in slowing in the average collection period from one month to two months. The relaxation in credit standards is expected to produce a 25% increase in sales. Assume that the firms required rate of return on investment is 20% before taxes. Bad debts losses will be 5% of incremental sales and collection expenses will increase by P20,000. Required: Should the company liberalize its credit policy? Solution: Incremental contribution margin from additional units (60,000 x P3) Less: Bad debts (P600,000 x 5%) Collection expenses Total Net incremental profit Required return on additional investment: Present level of receivables (2.4 million/12 mos.) Level of receivables after change in credit policy (3 million/6mos) Additional receivables Additional investment in receivables (P300,000 x 70%) Multiply by: Required return Required return on additional investment P180,000 30,000 20,000 P 50,000 P130,000 P200,000 500,000 P300,000 P210,000 20% P 42,000 Conclusion: In as much as the profit on additional sales of P130,000, exceeds the required return on the additional investment of P42,000, the firm would be well-advised to relax its credit standards. LESSON 4: MANAGEMENT OF INVENTORIES Objective of Inventory Management Inventory is the stockpile of the product the firm is offering for sale and components that make up a product. It is the responsibility of the financial officer to maintain a sufficient amount of inventory to ensure the smooth operations of the firm’s production and marketing functions and at the same time avoid tying up funds in excessive and slow-moving inventory. INVENTORY MANAGEMENT TECHNIQUES Inventory Planning Inventory planning involves the determination of what inventory quality, quantity, timing and allocation should be in order to meet future business requirements. The approach and mathematical techniques that may be used in determining inventory size, timing etc. include EOQ model and Reorder point. 1. Economic Order Quantity (EOQ) = a. Total inventory costs = Total ordering costs + Total carrying costs b. Total ordering costs = x Ordering costs per order c. Total carrying costs = Average Inventory x Carrying Costs per unit d. Average Inventory = EOQ = EOQ = EOQ = ( )( )( ) . EOQ = 163 units per order EOQ = EOQ = EOQ = ( )( , )( ) % EOQ = 3,162 units but since the order must be placed in multiples of 100 units, hence, the EOQ becomes 3,200 units. 2. Reorder point = Lead Time Usage + Safety Stock Level Monitoring and Inventory Control Systems Inventory control is the regulation of inventory within the predetermined limits. Effective inventory management should provide adequate stocks to meet the requirements of the business, while at the same time keeping the required investment to a minimum. Some of more generally known inventory control systems are as follows: 1. Fixed Order Quantity System This is a system wherein each time the inventory goes down to a predetermined level known as the reorder point, and order for a fixed quantity is placed. This system requires the use of perpetual inventory records or the continuous monitoring of the inventory level. 2. Fixed Reorder Cycle System This is also known as the periodic review or the replacement system where orders are made after a review of inventory levels has been done at a regular interval. An order is placed if at a time of the review the inventory level had gone down since the preceding review, the quantity ordered under this system is variable depending on usage or demand during the review period. Replenishment level is computed by the following formula: M = B + D (R + L) Where: M = replenishment level in units B = Buffer stock in units D = Average demand per day R = Time interval in days, between reviews L = Lead time in days 3. Optional Replenishment Systems This system represents a combination of important control mechanisms of the other two systems described above. Replenishment level is computed by the use of the following equation: P = B + D(L + R/2) Where: P = Reorder point in units B = Buffer Stock in units D = Average daily demand in units L = Lead time in days R = Time between review in days