Instructor’s Manual

Operations Strategy

Third Edition

Nigel Slack

Michael Lewis

For further instructor material

please visit:

www.pearsoned.co.uk/slack

ISBN: 978-0-273-74046-9

© Pearson Education Limited 2012

Lecturers adopting the main text are permitted to download and photocopy the manual as required.

Pearson Education Limited

Edinburgh Gate

Harlow

Essex CM20 2JE

England

and

Associated Companies around the world

Visit us on the World Wide Web at:

www.pearsoned.com/uk

---------------------------------First published 2002

This edition published 2012

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

The rights of Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis to be identified as authors of this work have been

asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Pearson Education is not responsible for the content of third-party internet sites.

ISBN: 978-0-273-74046-9

All rights reserved. Permission is hereby given for the material in this publication to be

reproduced for OHP transparencies and student handouts, without express permission of the

Publishers, for educational purposes only. In all other cases, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without either the prior written permission of

the Publishers or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the

Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd. Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. This

book may not be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the

Publishers.

ii

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Contents

Working with Operations Strategy: A tutor’s guide to teaching operations strategy

5

Operations strategy: Course plans

7

Teaching guides

1: Topic – Operations strategy – developing resources for strategic impact

2: Topic – Operations performance

3: Topic – Substitutes for strategy

4: Topic – Capacity strategy

5: Topic – Purchasing and supply strategy

6: Topic – Process technology strategy

7: Topic – Improvement strategy

8: Topic – Product and service development and organisation

9: Topic – The process of operations strategy – formulation and implementation

10: Topic – The process of operations strategy – monitoring and control

51

55

58

61

64

67

70

74

77

80

Extra cases and the topics covered in each case

Hagen style

Dresding Medical

‘Call-Us’ Banking Services

Freeman Biotest Inc.

Aztec Component Supplies

Zentrill

Bonkers Chocolate Factory

Ontario Facilities Equity Management (OFEM)

The Thought Space Partnership

Customer service at Kaston Pyral

Project Orlando at Dreddo Dan’s

The Focused Bank

Clever Consulting

Saunders Industrial Services

Geneva Construction and Risk

82

84

90

99

106

114

121

127

134

142

150

159

166

172

178

185

Study guide

Chapter 1: Operations strategy – developing resources for strategic impact

Chapter 2: Operations performance

Chapter 3: Substitutes for strategy

Chapter 4: Capacity strategy

Chapter 5: Purchasing and supply strategy

Chapter 6: Process technology strategy

Chapter 7: Improvement strategy

Chapter 8: Product and service development and organisation

Chapter 9: The process of operations strategy – formulation and implementation

Chapter 10: The process of operations strategy – monitoring and control

196

214

232

254

279

298

317

331

343

360

3

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Supporting resources

Visit www.pearsoned.co.uk/slack to find valuable online resources

For instructors

• Complete, downloadable Instructor’s Manual

• PowerPoint slides that can be downloaded and used for presentations

For more information please contact your local Pearson Education sales representative

or visit www.pearsoned.co.uk/slack

4

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Working with Operations Strategy

A tutor’s guide to teaching operations strategy1

Nigel Slack

Purpose

The purpose of this study guide is to support those colleagues who are adopting this book for

their operations strategy classes. Of course, all of us have our own style and approach to how

we try and communicate in class. So this guide is not intended as being in any way prescriptive.

However, it does contain materials that I use when teaching my own MBA and undergraduate

classes in this subject.

If you have any comments on how we can improve the book or on this teaching guide, please do

not hesitate to contact me at nigel.slack@wbs.ac.uk.

Content

Six types of material are included in this guide. They are

•

Course plans

•

Topic teaching guides

•

Extra cases and teaching notes

•

Student study guides

•

PowerPoint slides

Course plans

The section on course plans is intended as a guide to how the topic can be divided amongst a

number of sessions. Clearly, how this is done will depend on many factors, the most important

of which is the number of sessions available. Suggested topics are given for courses of one, two,

three, five, eight, ten and twelve sessions.

1

This tutor’s guide is intended to accompany ‘Slack N and Lewis M A (2011) Operations Strategy, 3rd

Edition, Financial Times Prentice Hall

5

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Topic teaching guides

A separate teaching guide is given for each topic (i.e. for each chapter of the text). This indicates

the cases that could be used to illustrate and demonstrate some of the issues in the topic. These

cases are drawn both from the cases included in the final section of the book and the extra cases

provided under ‘Extra cases and teaching notes’. Each teaching guide also contains a number of

discussion points, exercises and teaching tips which you may find useful.

Extra cases and teaching notes

In the first edition of Operations Strategy we included a ‘Case Exercise’ at the end of each of

the 15 chapters. Although these cases are no longer in the book itself, they are available in this

section of the teaching guide together with teaching notes that will help in debriefing the cases.

Student study guides

This section of the guide contains study guides that relate to each chapter in the text. These

study guides are relatively substantial pieces of work. They can be used either as a ‘background

primer’ for lecturers before they take a class in the topic. Alternatively, they can be copied and

handed out to students to support students’ individual learning before or after the relevant class.

It is hoped that these study guides together with the text will provide a complete learning

package that will support students in their studies.

PowerPoint slides

A full set of PowerPoint slides are included for each chapter. These sets of PowerPoint slides

contain not only some of the figures that are included in the text but other slides that you may

find useful in teaching. They are presented as a menu of slides rather than a prescription of how

you should teach the class. Please feel free to use only the ones that you find useful in

communicating the subject.

6

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Operations strategy

Course plans1

Putting a course curriculum together

Putting a course curriculum together depends on a number of factors, amongst which are

•

The time available (number and length of sessions)

•

The expressed needs of the students

•

The experience of the students

•

The other courses that students are studying

•

The preferences and competences of teaching staff

Given the almost infinite number of possible combinations that the list above could generate, it

would be a mistake to try and provide any prescriptive list of topics that should be included in a

course. However, the following table may provide a broad guide to how the chapters in Slack

and Lewis could be divided between sessions.

Session number

Number

of

sessions

1

1

Ch

1&2

2

Ch 1

Ch2

3

Ch 1

Ch 2

Ch

9&10

5

Ch 1

Ch 2

8

Ch 1

10

12

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Ch

4&5

Ch

6&7

Ch

9&10

Ch 2

Ch 3

Ch 4

Ch 1

Ch 2

Ch 3

Ch 1

Ch 2

Ch 2

9

10

Ch 5

Ch 6

Ch 9

Ch 10

Ch 4

Ch 5

Ch 6

Ch 7

Ch 8

Ch 9

Ch 10

Ch 3

Ch 4

Ch 5

Ch 6

Ch 7

Ch 8

Ch 9

11

12

Ch 10

Overview

Suggested topics that could be included in courses of various lengths are listed below.

1

All chapter numbers etc. refer to Slack N and Lewis MA (2011) Operations Strategy 3rd Edition, Financial

Times Prentice Hall

7

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

One session

What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

Performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

Decision areas

•

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

8

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Two sessions

Session 1 – What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher-level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations

capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

•

Performance objectives

•

Decision areas

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

Session 2 – Operations performance

Operations performance objectives

The five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

9

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Cost

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

•

The relative priority of performance objectives differs between different products and services

•

The polar representation of performance objectives

•

Order-winning competitive factors

•

Qualifying competitive factors

•

Delights

•

The benefits from order-winners and qualifiers

•

Criticisms of the order-winning and qualifying concepts

The relative importance of performance objectives change over time

•

Changes in the firm’s markets – the product/service life cycle influence on performance

•

Changes in the firm’s resource base

•

Mapping operations strategies

Trade-offs

•

What is a trade-off?

•

Why are trade-offs important?

•

Are trade-offs real or imagined?

•

Trade-offs and the efficient frontier

•

Improving operations effectiveness by using trade-offs

Targeting and operations focus

•

The concept of focus

•

Focus as operations segmentation

•

The ‘operation-within-an-operation’ concept

•

Types of focus

•

Benefits and risks in focus

•

Drifting out of focus

10

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Three sessions

Session 1 – What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher-level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

•

Performance objectives

•

Decision areas

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

Session 2 – Operations performance

Operations performance objectives

The five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

11

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

•

The relative priority of performance objectives differs between different products and services

•

The polar representation of performance objectives

•

Order-winning competitive factors

•

Qualifying competitive factors

•

Delights

•

The benefits from order-winners and qualifiers

•

Criticisms of the order-winning and qualifying concepts

The relative importance of performance objectives change over time

•

Changes in the firm’s markets – the product/service life cycle influence on performance

•

Changes in the firm’s resource base

•

Mapping operations strategies

Trade-offs

•

What is a trade-off?

•

Why are trade-offs important?

•

Are trade-offs real or imagined?

•

Trade-offs and the efficient frontier

•

Improving operations effectiveness by using trade-offs

Targeting and operations focus

•

The concept of focus

•

Focus as operations segmentation

•

The ‘operation-within-an-operation’ concept

•

Types of focus

•

Benefits and risks in focus

•

Drifting out of focus

12

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Session 3 – The process of operations strategy

Formulating operation strategy

Time and timing – fast and slow cycles

Strategic sustainability

‘Dynamic’ or offensive approaches to sustainability

Analysis for formulation

Capabilities

The challenges to operations strategy formulation

How do we know when the formulation process is complete?

•

Comprehensive

•

Correspondence

•

Criticality

Implementing operations strategy

Strategic monitoring and control

•

Expert control

•

Trial and error control

•

Intuitive control

•

Negotiated control

Monitoring implementation – tracking performance

•

Tracking the appropriate elements

•

Project objectives

•

Process objectives

The Red Queen effect

The balanced scorecard approach

The dynamics of monitoring and control

•

Tight alignment and loose alignment

13

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Implementation risk

Learning, appropriation and path dependency

•

Organisational learning

•

Single and double-loop learning

Appropriating competitive benefits

Path dependencies and development trajectories

The innovator’s dilemma

Resource and process ‘distance’

Stakeholders

14

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Five sessions

Session 1 – What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher-level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations

capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

•

Performance objectives

•

Decision areas

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

Session 2 – Operations performance

Operations performance objectives

The five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

15

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

•

The relative priority of performance objectives differs between different products and services

•

The polar representation of performance objectives

•

Order-winning competitive factors

•

Qualifying competitive factors

•

Delights

•

The benefits from order-winners and qualifiers

•

Criticisms of the order-winning and qualifying concepts

The relative importance of performance objectives change over time

•

Changes in the firm’s markets – the product/service life cycle influence on performance

•

Changes in the firm’s resource base

•

Mapping operations strategies

Trade-offs

•

What is a trade-off?

•

Why are trade-offs important?

•

Are trade-offs real or imagined?

•

Trade-offs and the efficient frontier

•

Improving operations effectiveness by using trade-offs

Targeting and operations focus

•

The concept of focus

•

Focus as operations segmentation

•

The ‘operation-within-an-operation’ concept

•

Types of focus

•

Benefits and risks in focus

•

Drifting out of focus

16

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Session 3 – Capacity and supply strategy

What is capacity strategy?

•

Capacity at three levels

•

The overall level of operations capacity

Forecast demand

Economies of scale

The number and size of sites

Capacity change

•

Timing of capacity change

•

Generic timing strategies

•

Leading, lagging or smoothing

•

The magnitude of capacity change

What is supply network strategy?

•

Supply network strategy

•

Why take a supply network perspective?

•

Global sourcing

Inter-operations relationships in supply networks

•

The outsourcing decision – vertical integration? Do or buy?

•

Traditional market-based supply

•

Partnership supply

Which type of relationship?

Network behaviour

Network management

Session 4 – Technology and improvement strategy

What is process technology strategy?

Process technology should reflect volume and variety

17

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Scale / scalability – the capacity of each unit of technology

•

Degree of automation / ‘analytical content’– what can each unit of technology do?

•

Degree of coupling / connectivity – how much is joined together?

The product–process matrix

•

Moving down the diagonal

•

Market pressures on the flexibility/cost trade-off?

Evaluating process technology

•

Evaluating feasibility

•

Evaluating acceptability

•

Evaluating vulnerability

Development and improvement

•

Breakthrough improvement

•

Continuous improvement

•

The differences between breakthrough and continuous improvement

Setting the direction

Developing operations capabilities

Deploying capabilities in the market

Session 5 – The process of operations strategy

Formulating operation strategy

Time and timing – fast and slow cycles

Strategic sustainability

‘Dynamic’ or offensive approaches to sustainability

Analysis for formulation

Capabilities

The challenges to operations strategy formulation

18

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

How do we know when the formulation process is complete?

•

Comprehensive

•

Correspondence

•

Criticality

Implementing operations strategy

Strategic monitoring and control

•

Expert control

•

Trial and error control

•

Intuitive control

•

Negotiated control

Monitoring implementation – tracking performance

•

Tracking the appropriate elements

•

Project objectives

•

Process objectives

The balanced scorecard approach

The dynamics of monitoring and control

•

Tight alignment and loose alignment

Implementation risk

Learning, appropriation and path dependency

•

Organisational learning

•

Single and double-loop learning

Appropriating competitive benefits

Path dependencies and development trajectories

The innovator’s dilemma

Resource and process ‘distance’

Stakeholders

19

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Eight sessions

Session 1 – What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher-level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

•

Performance objectives

•

Decision areas

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

Session 2 – Operations performance

Operations performance objectives

The five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

20

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

•

The relative priority of performance objectives differs between different products and services

•

The polar representation of performance objectives

•

Order-winning competitive factors

•

Qualifying competitive factors

•

Delights

•

The benefits from order-winners and qualifiers

•

Criticisms of the order-winning and qualifying concepts

The relative importance of performance objectives change over time

•

Changes in the firm’s markets – the product/service life cycle influence on performance

•

Changes in the firm’s resource base

•

Mapping operations strategies

Trade-offs

•

What is a trade-off?

•

Why are trade-offs important?

•

Are trade-offs real or imagined?

•

Trade-offs and the efficient frontier

•

Improving operations effectiveness by using trade-offs

Targeting and operations focus

•

The concept of focus

•

Focus as operations segmentation

•

The ‘operation-within-an-operation’ concept

•

Types of focus

•

Benefits and risks in focus

•

Drifting out of focus

21

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Session 3 – Capacity strategy

What is capacity strategy?

•

Capacity at three levels

•

The overall level of operations capacity

Forecast demand

•

Uncertainty of future demand

•

Changes in demand – long-term or short-term demand?

•

Long-term demand lower than short-term demand

•

Short-term demand lower than long-term demand

The availability of capital

The cost structure of capacity increments – break-even points

Economies of scale

Flexibility of capacity provision

The number and size of sites

Capacity change

•

Timing of capacity change

•

Generic timing strategies

•

Leading, lagging or smoothing

•

The magnitude of capacity change

Session 4 – Supply network strategy

What is supply network strategy?

•

Supply network strategy

•

Why take a supply network perspective?

•

Global sourcing

22

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Interoperations relationships in supply networks

The outsourcing decision – vertical integration? Do or buy?

•

Making the outsourcing / vertical integration decision

•

Deciding whether to outsource

•

Some advantages and disadvantages of outsourcing

Traditional market-based supply

•

Problems with relying on market mechanisms

•

The internet and e-procurement

•

Electronic market places

Partnership supply

•

Closeness

•

Trust

•

Sharing success

•

Long-term expectations

•

Multiple points of contact

•

Joint learning

•

Few relationships

•

Joint coordination of activities

•

Information transparency

•

Joint problem solving

•

Dedicated assets

Which type of relationship?

Network behaviour

•

Quantitative supply chain dynamics

•

Qualitative supply chain dynamics

•

Supply chain instability

23

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Network management

•

Coordination

•

Differentiation – matching supply network strategy to market requirements

•

Reconfiguration

•

Supply chain vulnerability

Session 5 – Process technology strategy

What is process technology strategy?

•

Direct or indirect process technology

•

Material, information and customer processing

Process technology should reflect volume and variety

Scale / scalability – the capacity of each unit of technology

Degree of automation / ‘analytical content’– what can each unit of technology do?

Degree of coupling / connectivity – how much is joined together?

The product–process matrix

•

Moving down the diagonal

•

Market pressures on the flexibility/cost trade-off?

Process technology trends

Evaluating process technology

•

Evaluating feasibility

•

Assessing financial requirements

•

Evaluating acceptability

•

Acceptability in financial terms

•

The life-cycle cost

•

The time value of money: net present value (NPV)

•

Limitations of conventional financial evaluation

24

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Acceptability in terms of impact on market requirements

•

Acceptability in terms of impact on operational resources

•

Tangible and intangible resources

•

Evaluating market and resource acceptability

•

Evaluating vulnerability

•

Vulnerability because of changed resource dependencies

Session 6 – Improvement strategy

Development and improvement

•

Process improvement

•

Breakthrough improvement

•

Continuous improvement

•

The differences between breakthrough and continuous improvement

•

The degree of process change

•

Improvement cycles

•

Direct, develop and deploy

Setting the direction

•

Performance measurement

•

What factors to include as performance targets?

•

The degree of aggregation of performance targets

•

The balanced scorecard approach

•

Which are the most important performance targets?

•

How to measure performance targets?

•

On what basis to compare actual against target performance?

25

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Benchmarking

•

Types of benchmarking

•

The objectives of benchmarking

Importance – performance mapping

The sandcone theory

Developing operations capabilities

•

The learning/experience curve

•

Limits to experience curve-based strategies

•

Process knowledge

•

The strategic importance of operational knowledge

Deploying capabilities in the market

•

The four-stage model

Session 7 – The process of operations strategy: formulation

and implementation

Formulating operation strategy

Time and timing – fast and slow cycles

Strategic sustainability

‘Dynamic’ or offensive approaches to sustainability

Analysis for formulation

Capabilities

The challenges to operations strategy formulation

How do we know when the formulation process is complete?

•

Comprehensive

•

Correspondence

•

Criticality

26

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Session 8 – The process of operations strategy: monitoring and

control

Implementing operations strategy

Strategic monitoring and control

•

Expert control

•

Trial and error control

•

Intuitive control

•

Negotiated control

Monitoring implementation – tracking performance

•

Tracking the appropriate elements

•

Project objectives

•

Process objectives

The Red Queen effect

The balanced scorecard approach

The dynamics of monitoring and control

•

Tight alignment and loose alignment

Implementation risk

Learning, appropriation and path dependency

•

Organisational learning

•

Single and double-loop learning

Appropriating competitive benefits

Path dependencies and development trajectories

The innovator’s dilemma

Resource and process ‘distance’

Stakeholders

27

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Ten sessions

Session 1 – What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher-level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

•

Performance objectives

•

Decision areas

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

Session 2 – Operations performance

Operations performance objectives

The five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

28

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

•

The relative priority of performance objectives differs between different products and services

•

The polar representation of performance objectives

•

Order-winning competitive factors

•

Qualifying competitive factors

•

Delights

•

The benefits from order-winners and qualifiers

•

Criticisms of the order-winning and qualifying concepts

The relative importance of performance objectives change over time

•

Changes in the firm’s markets – the product/service life cycle influence on performance

•

Changes in the firm’s resource base

•

Mapping operations strategies

Trade-offs

•

What is a trade-off?

•

Why are trade-offs important?

•

Are trade-offs real or imagined?

•

Trade-offs and the efficient frontier

•

Improving operations effectiveness by using trade-offs

Targeting and operations focus

•

The concept of focus

•

Focus as operations segmentation

•

The ‘operation-within-an-operation’ concept

•

Types of focus

•

Benefits and risks in focus

•

Drifting out of focus

29

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Session 3 – Substitutes for strategy

‘New’ approached to operations

Total quality management (TQM)

•

What is TQM?

•

The elements of TQM

•

Criticisms of TQM

•

Lessons from TQM

•

Where does TQM fit into operations strategy?

Lean operations

•

What is ‘lean’?

•

The elements of lean

•

Criticisms of lean

•

Lessons from lean

•

Where does lean fit into operations strategy?

Business process reengineering (BPR)

•

What is BPR?

•

The elements of BPR

•

Criticisms of BPR

•

Lessons from BPR

•

Where does BPR fit into operations strategy?

Six Sigma

•

What is Six Sigma?

•

The elements of Six Sigma

•

Criticisms of Six Sigma

•

Lessons from Six Sigma

•

Where does Six Sigma fit into operations strategy?

30

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Some common threads

•

Senior managers sometimes use these new approaches without fully understanding them

•

All these approaches are different

•

These approaches are not strategies but they are strategic decisions

•

Avoid becoming a victim of improvement ‘fashion’

Session 4 – Capacity strategy

What is capacity strategy?

•

Capacity at three levels

•

The overall level of operations capacity

Forecast demand

•

Uncertainty of future demand

•

Changes in demand – long-term or short-term demand?

•

Long-term demand lower than short-term demand

•

Short-term demand lower than long-term demand

The availability of capital

The cost structure of capacity increments - break-even points

Economies of scale

Flexibility of capacity provision

The number and size of sites

Capacity change

•

Timing of capacity change

•

Generic timing strategies

•

Leading, lagging or smoothing

•

The magnitude of capacity change

•

Balancing capacity change

31

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Location of capacity

•

The importance of location

•

The nature of location decisions

Session 5 – Supply network strategy

What is supply network strategy?

•

Supply network strategy

•

Why take a supply network perspective?

•

Global sourcing

Interoperations relationships in supply networks

The outsourcing decision – vertical integration? Do or buy?

•

Making the outsourcing / vertical integration decision

•

Deciding whether to outsource

•

Some advantages and disadvantages of outsourcing

Traditional market-based supply

•

Problems with relying on market mechanisms

•

The internet and e-procurement

•

Electronic market places

Partnership supply

•

Closeness

•

Trust

•

Sharing success

•

Long-term expectations

•

Multiple points of contact

•

Joint learning

•

Few relationships

32

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Joint coordination of activities

•

Information transparency

•

Joint problem solving

•

Dedicated assets

Which type of relationship?

Network behaviour

•

Quantitative supply chain dynamics

•

Qualitative supply chain dynamics

•

Supply chain instability

Network management

•

Coordination

•

Differentiation – matching supply network strategy to market requirements

•

Reconfiguration

•

Supply chain vulnerability

Session 6 – Process technology strategy

What is process technology strategy?

•

Direct or indirect process technology

•

Material, information and customer processing

Process technology should reflect volume and variety

Scale / scalability – the capacity of each unit of technology

Degree of automation / ‘analytical content’– what can each unit of technology do?

Degree of coupling / connectivity – how much is joined together?

The product–process matrix

•

Moving down the diagonal

•

Market pressures on the flexibility/cost trade-off?

33

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Process technology trends

Evaluating process technology

•

Evaluating feasibility

•

Assessing financial requirements

•

Evaluating acceptability

•

Acceptability in financial terms

•

The life-cycle cost

•

The time value of money: net present value (NPV)

•

Limitations of conventional financial evaluation

•

Acceptability in terms of impact on market requirements

•

Acceptability in terms of impact on operational resources

•

Tangible and intangible resources

•

Evaluating market and resource acceptability

•

Evaluating vulnerability

•

Vulnerability because of changed resource dependencies

Session 7 - Improvement strategy

Development and improvement

•

Process improvement

•

Breakthrough improvement

•

Continuous improvement

•

The differences between breakthrough and continuous improvement

•

The degree of process change

•

Improvement cycles

•

Direct, develop and deploy

34

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Setting the direction

•

Performance measurement

•

What factors to include as performance targets?

•

The degree of aggregation of performance targets

•

The balanced scorecard approach

•

Which are the most important performance targets?

•

How to measure performance targets?

•

On what basis to compare actual against target performance?

Benchmarking

•

Types of benchmarking

•

The objectives of benchmarking

Importance – performance mapping

The sandcone theory

Developing operations capabilities

•

The learning/experience curve

•

Limits to experience curve-based strategies

•

Process knowledge

•

The strategic importance of operational knowledge

Deploying capabilities in the market

•

The four-stage model

Session 8 – Product and service development and organisation

The strategic importance of product and service development

Developing products and services and developing processes

•

Product and process change should be considered together

•

Managing the overlap between product and process development

35

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Modular design and mass customisation

Product and service development as a process

Stages of development

•

Concept generation

•

Concept screening

•

Preliminary design

•

Design evaluation and improvement

•

Prototyping and final design

Developing the operations process

•

Product and service development as a funnel

•

Simultaneous development

A market requirements perspective on product and service development

•

Quality of product and service development

•

Speed of product and service development

•

Dependability of product service development

•

Flexibility of product and service development

•

The newspaper metaphor

•

Incremental commitment

•

Cost of product and service development

An operations resources perspective on product and service development

•

Product and service development capacity

•

Uneven demand for development

•

Product and service development networks

•

In-house and subcontracted development

•

Involving suppliers in development

•

Involving customers in development

36

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Product and service development technology

•

Knowledge management technologies

•

The organisation of product and service development

•

Project-based organisation structures

•

Effectiveness of the alternative structures

Session 9 - The process of operations strategy: formulation

and implementation

Formulating operation strategy

Time and timing – fast and slow cycles

Strategic sustainability

‘Dynamic’ or offensive approaches to sustainability

Analysis for formulation

Capabilities

The challenges to operations strategy formulation

How do we know when the formulation process is complete?

•

Comprehensive

•

Correspondence

•

Criticality

Session 10 – The process of operations strategy: monitoring

and control

Implementing operations strategy

Strategic monitoring and control

•

Expert control

•

Trial and error control

•

Intuitive control

37

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Negotiated control

Monitoring implementation – tracking performance

•

Tracking the appropriate elements

•

Project objectives

•

Process objectives

The Red Queen effect

The balanced scorecard approach

The dynamics of monitoring and control

•

Tight alignment and loose alignment

Implementation risk

Learning, appropriation and path dependency

•

Organisational learning

•

Single and double-loop learning

Appropriating competitive benefits

Path dependencies and development trajectories

The innovator’s dilemma

Resource and process ‘distance’

Stakeholders

38

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Twelve sessions

Session 1 – What is operations strategy?

What is ‘operations’ and why is it so important?

•

Three levels of input–transformation–output

What is strategy?

Operations strategy – operations is not always operational

•

Four perspectives on operations strategy

•

The top-down perspective – operations strategy should interpret higher-level strategy

•

The bottom-up perspective – operations strategy should learn from day-to-day experience

•

The market requirements perspective – operations strategy should satisfy the organisation’s

markets

•

The operations resource perspectives – operations strategy should build operations capabilities

The content and process of operations strategy

•

Performance objectives

•

Decision areas

Structural and infrastructural decisions

The operations strategy matrix

Session 2 – Operations performance

Operations performance objectives

The five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

39

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

The internal and external effects of the performance objectives

The relative priority of performance objectives

•

The relative priority of performance objectives differs between different products and services

•

The polar representation of performance objectives

•

Order-winning competitive factors

•

Qualifying competitive factors

•

Delights

•

The benefits from order-winners and qualifiers

•

Criticisms of the order-winning and qualifying concepts

The relative importance of performance objectives change over time

•

Changes in the firm’s markets – the product/service life cycle influence on performance

•

Changes in the firm’s resource base

•

Mapping operations strategies

Session 3 – Trade-offs and focus

Trade-offs

•

What is a trade-off?

•

Why are trade-offs important?

•

Are trade-offs real or imagined?

•

Trade-offs and the efficient frontier

•

Improving operations effectiveness by using trade-offs

Targeting and operations focus

•

The concept of focus

•

Focus as operations segmentation

•

The ‘operation-within-an-operation’ concept

•

Types of focus

40

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Benefits and risks in focus

•

Drifting out of focus

Session 4 – Substitutes for strategy?

‘New’ approached to operations

Total quality management (TQM)

•

What is TQM?

•

The elements of TQM

•

Criticisms of TQM

•

Lessons from TQM

•

Where does TQM fit into operations strategy?

Lean operations

•

What is ‘lean’?

•

The elements of lean

•

Criticisms of lean

•

Lessons from lean

•

Where does lean fit into operations strategy?

Business process reengineering (BPR)

•

What is BPR?

•

The elements of BPR

•

Criticisms of BPR

•

Lessons from BPR

•

Where does BPR fit into operations strategy?

Six Sigma

•

What is Six Sigma?

•

The elements of Six Sigma

41

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Criticisms of Six Sigma

•

Lessons from Six Sigma

•

Where does Six Sigma fit into operations strategy?

Some common threads

•

Senior managers sometimes use these new approaches without fully understanding them

•

All these approaches are different

•

These approaches are not strategies but they are strategic decisions

•

Avoid becoming a victim of improvement ‘fashion’

Session 5 – Capacity strategy

What is capacity strategy?

•

Capacity at three levels

•

The overall level of operations capacity

Forecast demand

•

Uncertainty of future demand

•

Changes in demand – long-term or short-term demand?

•

Long-term demand lower than short-term demand

•

Short-term demand lower than long-term demand

The availability of capital

The cost structure of capacity increments – break-even points

Economies of scale

Flexibility of capacity provision

The number and size of sites

Capacity change

•

Timing of capacity change

•

Generic timing strategies

42

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Leading, lagging or smoothing

•

The magnitude of capacity change

•

Balancing capacity change

Location of capacity

•

The importance of location

•

The nature of location decisions

Session 6 – Supply network strategy

What is supply network strategy?

•

Supply network strategy

•

Why take a supply network perspective?

•

Global sourcing

Interoperations relationships in supply networks

The outsourcing decision – vertical integration? Do or buy?

•

Making the outsourcing / vertical integration decision

•

Deciding whether to outsource

•

Some advantages and disadvantages of outsourcing

Traditional market-based supply

•

Problems with relying on market mechanisms

•

The internet and e-procurement

•

Electronic market places

Partnership supply

•

Closeness

•

Trust

•

Sharing success

•

Long-term expectations

43

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Multiple points of contact

•

Joint learning

•

Few relationships

•

Joint coordination of activities

•

Information transparency

•

Joint problem solving

•

Dedicated assets

Which type of relationship?

Network behaviour

•

Quantitative supply chain dynamics

•

Qualitative supply chain dynamics

•

Supply chain instability

Network management

•

Coordination

•

Differentiation – matching supply network strategy to market requirements

•

Reconfiguration

•

Supply chain vulnerability

Session 7 – Process technology strategy

What is process technology strategy?

•

Direct or indirect process technology

•

Material, information and customer processing

Process technology should reflect volume and variety

Scale / scalability – the capacity of each unit of technology

Degree of automation / ‘analytical content’– what can each unit of technology do?

Degree of coupling / connectivity – how much is joined together?

44

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

The product–process matrix

•

Moving down the diagonal

•

Market pressures on the flexibility/cost trade-off?

Process technology trends

Evaluating process technology

•

Evaluating feasibility

•

Assessing financial requirements

•

Evaluating acceptability

•

Acceptability in financial terms

•

The life-cycle cost

•

The time value of money: net present value (NPV)

•

Limitations of conventional financial evaluation

•

Acceptability in terms of impact on market requirements

•

Acceptability in terms of impact on operational resources

•

Tangible and intangible resources

•

Evaluating market and resource acceptability

•

Evaluating vulnerability

•

Vulnerability because of changed resource dependencies

Session 8 – Improvement strategy

Development and improvement

•

Process improvement

•

Breakthrough improvement

•

Continuous improvement

•

The differences between breakthrough and continuous improvement

•

The degree of process change

45

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Improvement cycles

•

Direct, develop and deploy

Setting the direction

•

Performance measurement

•

What factors to include as performance targets?

•

The degree of aggregation of performance targets

•

The balanced scorecard approach

•

Which are the most important performance targets?

•

How to measure performance targets?

•

On what basis to compare actual against target performance?

Benchmarking

•

Types of benchmarking

•

The objectives of benchmarking

Importance – performance mapping

The sandcone theory

Developing operations capabilities

•

The learning/experience curve

•

Limits to experience curve-based strategies

•

Process knowledge

•

The strategic importance of operational knowledge

Deploying capabilities in the market

•

The four-stage model

Session 9 – Product and service development and organisation

The strategic importance of product and service development

Developing products and services and developing processes

46

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Product and process change should be considered together

•

Managing the overlap between product and process development

•

Modular design and mass customisation

Product and service development as a process

Stages of development

•

Concept generation

•

Concept screening

•

Preliminary design

•

Design evaluation and improvement

•

Prototyping and final design

Developing the operations process

•

Product and service development as a funnel

•

Simultaneous development

A market requirements perspective on product and service development

•

Quality of product and service development

•

Speed of product and service development

•

Dependability of product service development

•

Flexibility of product and service development

•

The newspaper metaphor

•

Incremental commitment

•

Cost of product and service development

An operations resources perspective on product and service development

•

Product and service development capacity

•

Uneven demand for development

•

Product and service development networks

•

In-house and subcontracted development

47

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Involving suppliers in development

•

Involving customers in development

•

Product and service development technology

•

Knowledge management technologies

•

The organisation of product and service development

•

Project-based organisation structures

•

Effectiveness of the alternative structures

Session 10 – The process of operations strategy: formulation

and implementation

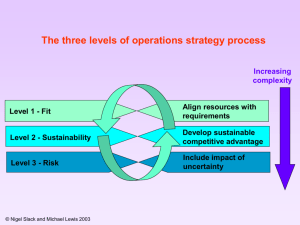

Formulating operation strategy

Time and timing – fast and slow cycles

Strategic sustainability

‘Dynamic’ or offensive approaches to sustainability

Analysis for formulation

Capabilities

The challenges to operations strategy formulation

How do we know when the formulation process is complete?

•

Comprehensive

•

Correspondence

•

Criticality

Session 11 – The process of operations strategy: monitoring

and control

Implementing operations strategy

Strategic monitoring and control

•

Expert control

48

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Trial and error control

•

Intuitive control

•

Negotiated control

Monitoring implementation – tracking performance

•

Tracking the appropriate elements

•

Project objectives

•

Process objectives

The Red Queen effect

The balanced scorecard approach

The dynamics of monitoring and control

•

Tight alignment and loose alignment

Implementation risk

Learning, appropriation and path dependency

•

Organisational learning

•

Single and double-loop learning

Appropriating competitive benefits

Path dependencies and development trajectories

The innovator’s dilemma

Resource and process ‘distance’

Stakeholders

Session 12 – Overview

Operations strategy revisited

Applying the operations strategy matrix

Revisiting the five generic performance objectives

•

Quality

•

Speed

49

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

•

Dependability

•

Flexibility

•

Cost

Revisiting the decision areas

•

Capacity

•

Supply networks

•

Technology

•

Improvement

•

Product/service development

Revisiting process

•

Alignment

•

Implementation

Operations strategy is close to operations management

Future trends

•

Technology

•

Globalisation

•

Corporate social responsibility

50

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Operations Strategy

TEACHING GUIDE 1

Topic – Operations strategy – developing

resources for strategic impact

Reading(s)

(This section includes the relevant chapter of Slack and Lewis plus any additional reading that

may be particularly helpful)

Chapter 1 of Slack and Lewis

Hayes, R.H., Pisano, G.P., Upton, D.M. and Wheelwright, S.C. (2004) Operations, Strategy,

and Technology: Pursuing the Competitive Edge. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Cases

(This section refers to potential cases for use in class sessions. They are either included in the

Case study section of Slack and Lewis or in the ‘Extra case studies section of this Instructors

Manual)

•

McDonald’s Corporation (Abridged)

•

‘Hagen Style’

•

Dresding Medical

•

The Focused Bank

•

Contact Utilities

•

IDEO Service Design

Teaching this topic

Key questions

Why is operations excellence fundamental to strategic success?

What is strategy?

What is operations strategy?

51

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

How should operations strategy reflect overall strategy?

How can operations strategy learn from operational experience?

How do the requirements of the market influence operations strategy?

How can the intrinsic capabilities of an operation’s resources influence operations strategy?

What is the ‘content’ of operations strategy?

What is the ‘process’ of operations strategy?

The objective of teaching this topic is primarily to convince students that operations

management isn’t always ‘operational’. Although Operations Management does deal with the

more operational aspects of the operations functions’ activities, operations managers have a

very significant strategic role to play. It is also important to demonstrate that there is a whole

range of performance criteria that can be used to judge an operation, and which operations

managers influence. ('…..although cost is important and operations managers have a major

impact on cost, it is not the only thing that they influence. They influence the quality that

delights or disappoints their customers, they influence the speed at which the operation responds

to customers’ requests, they influence the way in which the business keeps its delivery promises

and they impact on the way an operation can change with changing market requirements or

customer preference. All these things have a major impact on the willingness of customers to

part with their money. Operations influence revenue as well as costs.')

It is also vital to stress to students the importance of how the operations function sees its role and

contribution within an organisation. ('… you can go into some organisations and their

operations function is regarded with derision by the rest of the organisation; how come, they

say, that we still can’t get it right. This is not the first time we have ever made this product or

delivered this service. Surely we should have learned to get it right by this time! The operations

people themselves know that they are failures, the organisation does nothing but scream at

them, telling them so….. Other companies have operations functionaries who see themselves as

being the ultimate custodian of competitiveness for the company. They are the A team, the

professionals, the ones who provide the company with all they need to be the best in the

market…')

Other objectives are

•

To explain that there really is something very important embedded within operations and

processes. The skills of people within the operation and the processes they operate are the

repository of (often, years of) accumulated experience and learning.

•

To give examples of how markets and operations must be connected in some way. Whether

this is because operations are being developed to support markets, or markets are being

sought that allow operations capabilities to be leveraged, it doesn’t matter. The important

issue is that there should always be a connection between the two.

Possible lesson elements

Teaching hint – Teaching the nature and importance of the various performance objectives can

be done in two ways.

52

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

One can look at each performance objective in turn, using examples of where the particular

performance objective has a special significance. For example,

•

Quality – Use companies (like Bentley or Toyota) that have a reputation for quality

products or services. High quality hotels and restaurants can be used, as can luxury services

such as high price hairdressers, etc. This can prompt a useful discussion regarding what we

mean by quality (although you may wish to reserve this for the lesson on quality).

Alternatively, use an example where high conformance is necessary for safety reasons such

as blood testing in hospitals.

•

Speed – Any accident, emergency or rescue service is useful to discuss here. The

consequences of lack of speed are immediately obvious to most students. Also, use

transportation examples where different speeds are reflected in the cost of the service. First

and second class postage is an obvious example as are some of the over-night courier

services. Likewise, the fast check-in service offered to business class passengers at airports

and the exceptionally fast service of Concorde (depending on whether it is flying when you

are reading this!) that offers a fast service at a very high price.

•

Dependability – Some of the best examples to use here are those where there is a fixed

‘delivery’ time for the product or service. Theatrical performances are an obvious example

(or the preparation of lectures). Other examples include space exploration projects that rely

on launch dates during a narrow astronomical ‘window’.

•

Flexibility – We have found the best examples here to be those where the operation does not

know who or what will ‘walk through the door’ next. The obvious example would be a

bespoke tailor who has to be sufficiently flexible to cope with different shapes and sizes of

customers and also (just as importantly) different aesthetic tastes and temperaments. A more

serious example would be the oil exploration engineers who need to be prepared to cope

with whatever geological and environmental conditions they find drilling for oil in the most

inhospitable parts of the world. Accident and emergency departments in hospitals can also

provide some good discussions. Unless they have a broad range of knowledge that allows

them to be flexible they cannot cope with the broad range of conditions presented by their

patients.

•

Cost – Use the example of low-cost retailers who have achieved some success in parts of

Europe by restricting the variety of goods they sell and services they offer.

Teaching hint – Try establishing the market-operations link by referring to organisations

familiar to the students. Even the ubiquitous McDonalds can be used (in fact there is a very

good case on McDonald’s operations in the Harvard Business School series; contact The Case

Clearing House for details). The important issue however is to raise the focus of discussion from

managing a single part of the organisation (such a single McDonald’s store) to managing the

operations for the whole organisation (for example, what are the key operations strategy

decisions for McDonald’s in the whole of Europe?). The discussion can then focus on the

difference between the two levels of analysis. Discussions can especially look at how the

operational day-to-day issues (such as, the way staff are scheduled to work at different times in

McDonald’s stores) can affect the more strategic issues for the organisation as a whole (such as,

what level of service and costs are McDonald’s franchise holders expected to work to?).

53

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Exercise – One method of establishing the connection between markets and operations is to ask

the class members to find a business-to-consumer website, formally list the ‘marketing’

promises that the website makes and then think about the operations implications of these

promises. For example, what will the company have to do in terms of its inventory management,

warehouse locations, relationships with suppliers, transportation, capacity management and so

on in order to fulfil its promises?

54

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Operations Strategy

TEACHING GUIDE 2

Topic – Operations performance

Reading(s)

(This section includes the relevant chapter of Slack and Lewis plus any additional reading that

may be particularly helpful)

Chapter 2 of Slack and Lewis

Boyer, K.K. and Lewis, M.W. (2002) Competitive priorities: investigating the need for tradeoffs in operations strategy. Production and Operations Management, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 9–20.

Cases

(This section refers to potential cases for use in class sessions. They are either included in the

Case study section of Slack and Lewis or in the ‘Extra case studies’ section of this Instructors

Manual)

•

Hagen Style

•

Dresding Medical

•

Call-Us Banking Services

•

The Thought Space Partnership

•

Customer Service at Kaston Pyral

•

The Focused Bank

•

Clever Consulting

•

Saunders Industrial Services

•

Disneyland Resort Paris

•

The Greenville operation

•

McDonald’s Corporation (Abridged)

•

Contact Utilities

•

IDEO Service Design

55

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Teaching this topic

Key questions

What are operations performance objectives?

Do the role and key performance objectives of operations stay constant or vary over time?

Are trade-offs between operations performance objectives inevitable or can they be

overcome?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of focused operations?

This chapter covers four important issues relating to operations performance. The chapter is

placed at the beginning of the book because it provides some of the basic ideas that reoccur

throughout the treatment of the various topics in both the content and process of operations

strategy. However, it could equally well have been placed towards the end of the book if one

wanted to relate back to the various examples used throughout the book in order to demonstrate

the nature of operations performance. So, from a teaching perspective, one might want to think

about delaying some of these issues towards the end of the course.

The four issues related to operations performance that are covered in the chapter are as follows:

•

There are five ‘generic’ performance objectives. However, note that one may introduce a

broader perspective on operations performance at this point, including aspects of corporate

social responsibility (CSR) and so on.

•

The relative importance of these performance objectives changes over time. The text uses

the VW example to illustrate this over a number of decades. But several of the cases listed

above could also be used to demonstrate this point.

•

There are trade-offs between the various performance objectives. The text uses the ‘efficient

frontier’ concept to illustrate this. But in addition, it is worthwhile exploring the debate over

whether trade-offs are real or imagined, and in particular the idea that trade-offs are very

real in the short term but can be overcome in the long term.

•

Focussing an operation on a very small number of performance objectives can lead to

superior performance in those objectives. This is the classic ‘focussed factory’ idea that

Skinner raised several decades ago. Of course, it applies equally to non-manufacturing

operations.

Possible lesson elements

Teaching hint – An important point to get over here is that performance objectives differ for

different operations with different strategies. It may seem obvious but it is fundamental and not

all students grasp this initially. An obvious way of demonstrating this is to take two well-known

companies in different parts of the same sector competing in different ways. For example, ask

the students to contrast a well-known low-cost airline such as Ryanair with Virgin Atlantic’s

Upper Class service.

56

© Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis 2012

Nigel Slack and Michael Lewis, Operations Strategy, 3rd Edition, Instructor’s Manual

Exercise – Relating to the above point, one could ask students to explore the websites of two

organisations such as Ryanair and Virgin and from that deduce differences between the relative

importance of each performance objective.

Discussion point – ‘Surely the level of service offered by Ryanair is now so low that customers

will not be prepared to put up with it even at rock bottom prices?’

Exercise – The text quotes various statements from the website of some well-known companies

that emphasise one or more performance objectives. One could ask students to explore some

other company websites and identify their stated performance priorities.

Teaching hint – Polar diagrams are particularly useful when summarising any company’s

performance objectives. What ever company is being discussed, it is useful to have a summary

of its strategic stance in the form of a polar diagram.

Exercise – One can refine the idea of the relative importance of performance objectives by

asking students to distinguish between qualifiers, order winners and delights. Any of the ideas

already mentioned can be used to do this.

Exercise – The idea of delights is especially useful for teaching experienced students. One can

ask them to identify one product or service and ask them to distinguish between qualifiers, order

winners and delights now and in the future. See the study notes associated with Chapter 2 for