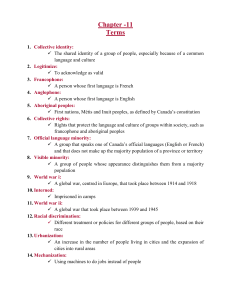

Unequal Relations: Race, Ethnic, Aboriginal Dynamics in Canada

advertisement