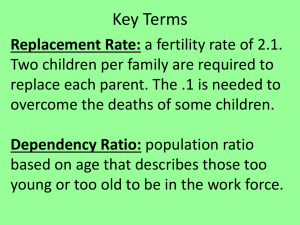

Meet The Team Lopez, Jasmine Alexa Ubalubao, Avril Apostol, Michelle Overview Global economy is the exchange of goods and services integrated into a huge single global market. It is virtually a world without borders, inhabited by marketing individuals and/or companies who have joined the geographical world with the intent of conducting research and development and making sales. International trade permits countries to specialize in the resources they have. Countries benefit by producing goods and services they can provide most cheaply and by buying the goods and services other countries can provide most cheaply. International trade makes it possible for more goods to be produced and for more human wants to be satisfied than if every country tries by itself to produce everything it needs Learning Outcomes • Compare the global demography before and after transition; • Analyze current population pyramids to predict future population trends; • Evaluate how population cartograms influence perspective of geographic regions; Learning Outcomes • Summarize connections between multiple quality of life indicators for low, middle, and high income countries; and • Draw conclusions from each of the demographic transition stages. Indicative Content 1. Global demography before and after transition 2. Current population trends 3. Influence of population cartograms 4. Quality of life indicators 5. Demographic transition stages Global Demography Demography refers to the study of human populations and the process through which populations change in respect to environment, geography, and climate. DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION Refers to the transition from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates as a country develops from a pre-industrial to an industrialized economic system. RELEVANCE OF GLOBAL DEMOGRAPHY Structures of human demographic behavior are particularly helpful in dealing with the future. Hence, the history of the population is a quasinavigator who cannot foresee the thunderstorm, but who can weather its consequence with the help of a compass. In demography, one element very relevant for the interpretation of major social, economic, and political forces is the changing pattern of the geodemography of the world. To ignore the impact that the profound variation in the relative weights of human populations has had on the “world order” WORLD ORDER It is tantamount to depriving oneself of a powerful tool of interpretation and were established internationally for preserving global political stability. (Teitelbaum, 2015). The diverging demographic cycles are taking place in various continents, regions, and countries. Survival became precarious as it was constrained by the poverty of knowledge. Before modern demographic transition in the 18th century, voluntary fertility control was not unknown but it was limited to small sectors of the population with only marginal effects at the aggregate level. Small differences in the rates of growth can generate large differences in population if sustained long enough. The demographic transition and its timing, spanning over two centuries, coupled with greatly increased potential for growth, produced powerful changes in geodemographic. These innovations were the results of the various timing of the transition. • In Europe, the share of the world population rapidly increased from 16% in 1820 to 19% 50 years later. • In Africa, its population increased even faster, being higher than in the 19th century. Its growth is projected from 9% in 1950 to an astounding 25% in 2050. THE EXTINCTION OF MAN Will mankind become extinct? • Pessimists or those that tends to see the worst aspect of things believe that extinction might happen soon. • In comparison Optimists, the end of mankind is inevitable, but will occur in the indeterminate future. • Based on studies, many became extinct because of fragmentation and isolation that led to communities falling under a minimum sustainable size. Fragmentation/Isolation is separating issues relating to people of color and women (or other protected groups) from the main body of text. (e.g. racism, discrimination, exploitation, oppression, sexism, and intergroup conflict). • In an interconnected and densely settled world, the cause of extinction is highly improbable. • Populations disappeared because of natural or man-made catastrophes. • However, even if mankind is better equipped than in the past to withstand the natural events, it is probably more vulnerable to man-made disasters. • Another significant cause of extinction is known as demographic suicide. • Demographic Suicide refers to the continuous and structural imbalance between births and deaths. • The extinction of the native populations of the Caribbean in the 19th century and of the Tasmanians or the Fuegians in the 19th are good examples, the decline was the consequence of disruption brought about by contact with the Europeans. • Populations also disappeared because they “lost” their identity through mixing with other groups. • In a globalized world, where migration are intermarriage are expected to increase, mixing will probably become a major force in shaping societies, determining changes of identities or even wiping out the distinctive features of a population. • In the late 18th, 19th and 20th centuries in Europe, the powerful driving force of population change was mortality. • Patterns of mortality rate before have a profound impact on population growth. Mortality evolves because of genetic mutations and drift, and social inheritance through changing interactions between humans, microbes, animal vectors, and the environment. New diseases appear, old ones reemerge, others lose or increase their virulence, some vanish. These had a variable impact on general mortality. • The issue of fertility also has always been an extremely robust and resilient characteristic of the past populations. • Two major factors could jeopardize the enormous advances of survival achieved during the last century, or cripple future progress. • First, is any unforeseen modification of the system of pathologies through the emergence of new deadly diseases as well as the resilience of old diseases. • Second factor is the possible economic unsustainability of modern health care of public systems, threatened by rising costs and demographic aging. Rising costs produce a retrenchment of public health care and restricted accessibility to health services, more inequality and more vulnerability can be generated, with negative consequences for survival. Population Rebound and Adjustments • Precipitous phases in the demographic cycle are always followed by “rebounds” or by “adjustments” of the demographic system. • These typically follow the “ancient regime” type of crisis-plague, smallpox, or cholera as examples. Precursors includes; *A rise of cereal prices because of adverse weather *A man-made event like war *A major epidemic of typhoid fevers, and typhus or other diseases and, *A parasite that destroys a main staple • Homoeostatic implies the existence of an inner, almost automatic, capacity of the demographic system to adopt to changing external constraints • Adjustment generally requires time, and unlike rebounds, whose mechanisms are relatively clear, adjustment factors are complex and variable. SPECIFIC FACTORS OF ADJUSTMENT • Population growth and a growing pressure on the available resources are viewed as forces that put in motion responses tending to minimize and contain the negative outcomes. Responses may be of a general economic nature like the advances in technology and productivity, etc. • Adjustments of the demographic system leading to a lower rate of growth, or any combination of the two. Example • In many European populations the great plague cycle of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries brought about many profound changes in the economy like the lower density, more land available, more extensive cultivation as well as in the demographic setting, which involves the restructuring of families in larger and more complex units, higher fertility, and changes of the marriage pattern (Blockmans and Dubois, 1997; Livi-Bacci, 2000). • In Japan, the long cycle of population growth of the early Tokugawa period terminating in the first decades of the eighteenth century was followed by a period of quasi-stagnation until the second third of the nineteenth century, through marriage control and infanticide (Hayami, 2009) • Rebounds would definitely happen in the future as a response to catastrophic events • A central issue is the extremely low fertility of many countries in Europe and Eastern Asia. There is consensus that current low fertility will give way to a gradual recovery • Declining fertility, possibly leading to unsustainable population decline, may be redressed, though the factors of the adjustment • Since very low fertility generates damaging negative economic externalities, states may react by channeling more resources to couples and families, inducing them to have more children • Possibility is countries becoming open to immigration even though strong public sentiment about national identity has so far prevented such a move; Japan, for instance, may in the future change its restrictive stance. Compare the global demography before and after transition • During this post modern world, the birth rates remain high but the death rates drop, causing the overall population to increase. The theory of demographic transition predicts how a population will change over time in regards to the mortality and fertility rates as well as age composition and life expectancy. Fertility Issues Low fertility, below the level of replacement, has been an exceptional occurrence in the past. Only the destruction of fertility foundations, such as lack of mating opportunities, forced separation of couples, loss of libido, and decreased fecundity due to infections, hunger, or stress, has resulted in a diminished reproductive capacity. In England, fertility remained below replacement level for most of the century after the plague cycle in 1348 (Hollingsworth, 1969). Evidence of fertility below replacement in the Caribbean islands after contact with Europe is also present, with native populations becoming extinct during the sixteenth century due to compromised natural reproduction foundations. Livi-Bacci (2008) also notes some indirect evidence of low fertility in Mexico during the same century. Fertility levels have shown remarkable resilience even during exceptional distress, as demonstrated by the Guarani of the 30 missions of Paraguay during the catastrophic period between 1733 and 1767. Livi-Bacci (2008) highlights the high fertility levels of the past populations, which were robust and resilient. Charles Darwin's human species, which originated in equatorial Africa, evolved continuously to make settlement possible in extreme corners of the two hemispheres. As humans spread widely, they must have been exposed to diverse conditions during their incessant migration. Overall, fertility levels have remained high and resilient even during challenging times. Migration flows have evolved since agriculture's invention, with waves of people settling in unpopulated or large open spaces. These migration flows have two primary features: the ability to adapt to diverse environments and the ability of families and settlements to generate a demographic surplus for further expansion. The first wave of migrants, with their high reproductive fitness and rate of growth, were chosen based on factors such as age, health, strengths, stamina, and willingness to face new experiences. The demographic surplus generated by these waves was crucial for the expansion of the new lands. Large families with many children, with ample land for agriculture, had the demographic features required for a successful economy, making them a significant factor in the selection of potential migrants. In urban and industrial settings, migrant groups had to be mobile, adaptable, and flexible, traveling with small families and moderating fertility once settled. This advantage was likely to favor integration and upward mobility. The reproductive advantage of first-generation immigrants over native populations was almost zero, as the convergence of reproductive patterns between immigrants and natives often led to rapid convergence. Mobility is not driven mainly by natural factors, but by policies and regulations, particularly after the rise of nation states. Future questions are whether migration will select individuals most likely to be successful and how this will happen. Stages of Demographic Transition • Mortality Decline The mortality decline in Europe began around 1800, marked by the development of the smallpox vaccine, public health measures, effective quarantine measures, and improved personal hygiene. This led to improvements in health and nutrition as income grew. Highincome countries achieved potential mortality reductions due to reductions in chronic and degenerative illnesses, including heart diseases and cancer. • Fertility Decline Marital fertility declined in most European states by 40% between 1870 and 1930, driven by couples' desire for surviving children. Economic changes impact fertility by increasing the cost and benefits of child-bearing. Technological progress and growing physical and human capital have made child-bearing more time-intensive, making children more expensive. Women's productivity also varies, making children more expensive and reducing their economic contributions. Higher-income parents allocate more resources to each child, leading to fewer children in the family. • Population Growth The demographic transition towards a gain in life expectancy is causing small changes in fertility and mortality rates. India has higher initial fertility and mortality rates than Europe and least developed countries. Europe achieves 1.5% population growth but a plunge in fertility rates, leading to a 1% yearly population decline. The actual European population growth rate is nearly zero by 2050. • Shifts in Age Distribution Demographic transitions involve changes in fertility, mortality, and growth rates, but also systematic innovations in age distribution, known as dependency ratios. These ratios consider the younger or older population and divide by the working age population. Mortality declines in the first stage, leading to an increase in children and dependency ratios. As the population grows, families have more surviving children, causing challenges in achieving educational goals for the unexpectedly increased number of children. DEMOGRAPHIC IMPACT ON ECONOMY AND SOCIETY The transition of global demography has significantly restructured human populations, increasing population size by a factor of 6 and potentially reaching a factor of 10 by 2100. The ratio of elders to children will grow by 10 to 50 times, with a tripled lifespan and a drop in births per woman. Women spent 70% of their adult years bearing and raising children, but due to lower fertility and longer life, these data decreased in many parts of the continent. Thomas Malthus argued that slow population growth was balanced with a slowly growing economy. Faster population growth would depress wages, leading to increased mortality due to famine, war, or disease. This was known as the positive check, while depressed wages also led to postponement of marriage, prostitution, vices, and contraception. As population growth could potentially outpace the economy, it was always held in check. Finn and Livi-Bacci discuss the early marriage in Western Europe, where a separate household was required for maintaining. Women's first marriage was often late, with an average age of 25 years. Livi-Bacci highlights the moderate fertility rate (4 to 5 births per woman) and high mortality rate (25 to 35 years), influenced by high mortality in infancy and childhood. Bhat's research on India's fertility rate during World War II revealed a low life expectancy and variable fertility rates. PostWW II, third world countries experienced a higher TFR due to contraceptive effects, sex taboos, abortion practices, and marriage patterns. Despite not being as strong as Western Europe, India's fertility rate was still 6-7 births per woman. CONSEQUENCES OF THE DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION The demographic transition from 1800 to 2100 saw a rise in the total population from 1 billion to 9.5 billion, largely due to uncertainty on future fertility. The European population is projected to decline by 13% between now and 2050, while other developed countries experience negative population growth rates. The transition retools the world's population, with the average life expectancy increasing and the median age doubling. Becker and Willis' research highlights a decline in childbearing capacity and greater longevity, leading to a focus on other activities in adult years. This shift, combined with increased joint survivorship and intergenerational intensified kin networks, results in a greater emphasis on other activities in adult years. Manton, Corder and Stallard, Freedman, Martin and Schoeni, and others have all contributed to the quality-quantity trade theory, highlighting the importance of investing in each child's health and functional status. Longer life periods, resulting from declining mortality, can significantly impact the health and functional status of the surviving population, highlighting the importance of this trade-off in achieving optimal health. Wise and Gruber's study highlights the significant effect of public pension programs and heavy implicit taxes on workers in industrial states since the 1960s. This has led to an increase in early retirement rates, resulting in parametric reforms with pay-as-you-go defined benefit programs, which reduce benefits, raise taxes, and eliminate incentives for early retirement. Lee and Miller highlight the significant fiscal externalities that contribute to the growth of health centers and pensions in developing states. These externalities, resulting from the aging population and age-related public transfer systems, can result in substantial benefits for the elderly, thereby incentivizing child-bearing. However, in developing states with younger populations and public programs focusing on children, the fiscal externalities and incentives can be reversed. On a global level, demographic pressures and controversial issues impact international migration. Developed countries face increasing international migration from third world countries, while population growth slows or declines in developed countries. The net international migration of developed countries has increased from near-zero in the 1950s to around 2.3 million per year in the 1990s. The dramatic aging of the population, characterized by low fertility and long life, is an unstoppable stage of the global demographic transition. This transition presents economic and political challenges, necessitating the adaptation of life cycle plans to the ever-changing circumstances in capitalintensive, culturally diverse advanced countries.