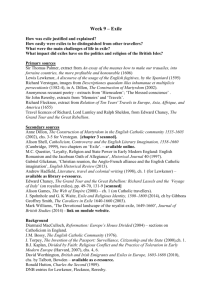

IFSCA Course Manual Developing Skills and Competencies in the IFS Model Derek Scott, Founder and CEO, IFSCA & Elyse Heagle We are a Habitat “We live in symbiosis with a population of inner people who exist in multiple relational subsystems, much as we have symbiotic relationships with the millions of microbes in the gut, which are in relationship with each other. We are a habitat. The citizens (parts) of this habitat can be hurt and can get into conflict with each other, engaging in mutual injury, self-attack, and defensive (or offensive) maneuvers. The good news is that we also have a Self that is ready to provide stewardship to our inner system. Once we appreciate the disparate characters and perspectives of all of our parts we can stop expending energy disapproving of ourselves (or anyone else) for being inconsistent, having mixed feelings, or hosting inner conflict. Though our inner communities can be divided by conflict, they are also full of gifts. When our parts separate from the seat of consciousness (the Self) we discover what spiritual traditions have known and taught for thousands of years: that we have the resources we need to support and protect this vulnerable inner population with its awesome potential. Self-acceptance is the ongoing process of welcoming all parts and banishing none. When we pursue the ideal of self-acceptance we also gain the freedom to live by curiousity, exploration and inclusion.” Internal Family Systems (2nd Ed.) pp. 42 Richard C. Schwartz Martha Sweezy IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca Contents Module #1 “Just Ask” Pg. 1 Pg. 2 Pg. 5 Pg. 8 Pg. 9 Pg. 12 History, language, and assumptions Protectors and exiles Self Goals of the model How to do an IFS session IFS Questions Module #2 “What’s the Worry?” Pg. 14 Pg. 24 Pg. 28 Pg. 30 Pg. 31 Working with protectors Firefighters Exiles & Questions to ask them Shame & Non-Burdened Exiles Updating Module #3 “Who’s Here?” Pg. 33 Pg. 37 Pg. 46 Therapist Parts Article: Multiplicity and Internal Family Systems Therapy – A New Paradigm? – Derek Scott Article: Self-leadership and the Fire Drill Exercise – Richard Schwartz Module #4 “I’m Here” Pg. 50 Pg. 51 Pg. 53 Pg. 56 Pg. 58 Pg. 59 Self-leadership The Self-led Therapist Compassion does not fatigue Therapy as Service 5 P’s and the Laws of Inner Physics Article: Embrace Your Self-Destructive Impulses? How People Can Connect with Dark Parts of Their Psyche for Personal Change – Richard Schwartz IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca Beyond the Basics Pg. 66 Healing at a cellular level: IFS & Neuroscience - Elyse Heagle Pg. 69 The IFS Process through a Neuroscience Lens Pg. 73 Polarisations Pg. 75 Legacy Burdens and Shame Pg. 77 Legacy Burdens – Elyse Heagle Pg. 82 IFS & Addictive cycles Pg. 85 IFS & Couples IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca Module 1 “Just Ask” The Basic Model IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca The History and language This model of therapy was developed by Richard Schwartz in the 80s and 90s. It has its roots in Family Systems Therapy and has evolved several times through Dick’s conversations and work with other therapists. There are several good books that explain its origins, and for the sake of building your skills and competence in the model, we are going to focus mostly on the model and how to use it. This is not the only model to talk about people as having sub-personalities and is also not the first to see the sub-personalities as having an awareness of one another and some sort of relationship but is the first to see them in relation to an over-arching Self who is ideally the leader of the system. It is the inclusion of Self that positions IFS as a psychospiritual therapeutic model. Assumptions: 1.We all have parts and a Self. 2. All parts are valuable, and our protective parts all have good intent, although it may not appear that way at first glance. There are no “bad” parts, and a goal of this therapy is not to eliminate parts, but instead to help them find their non-extreme role. 3. As we develop, our parts form relationships with one another much the way a family does, and we can see all kinds of complex relationships within our systems. Parts may be polarised with each other (different and opposite opinions/agendas), or supportive, or operate as part of a cluster. 4. As we work with our own and clients' systems they will re-organise and can change rapidly, sometimes in ways that we only become aware of later. Changes may occur “behind the scenes”. 5. Parts can get stuck in extreme roles or carrying extreme beliefs and feelings, and can be freed up to choose something else, if they believed it would be safe to do so 6. Changes can be made in the internal or external worlds and both will be influenced by the other, however changes in our internal worlds do not necessarily require us to make changes in our external worlds/relationships. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 1 Protectors and Exiles These are the two typical roles our parts take on. Protectors are easily identified as they always have an agenda or strategy connected to the distress held by the exile. Proactive Protectors - The Managers Our managers like to run our lives. They do our banking, plan our vacations, get us to work, and like to appeal to the rational. They are concerned with social mores and ensuring that we look our best and are “good people”. Their values are often acquired at a very young age through the influences of the family of origin and the broader culture that define how to be “good”. Because they often take on their roles when we are young, managers are much like parentified children in families; unequipped to lead but feeling as if they have no choice as they hold closely the attitude of ‘never again’. Consequently, they often do not know how old the system is in present day. When operating in their protective roles they work to ensure the vulnerable exiles do not get triggered, hoping to prevent the exiles emerging into consciousness and hijacking the system with their distress. Manager strategies that present with extreme rigidity and severity often mirror the degree to which this part believes the exile is in danger of being reinjured. Furthermore, the system will begin to rely heavily on a manager that is competent in its role (of not triggering the exile). Yet when we get to know these parts, they often share how overwhelmed they feel by their responsibility and power. Manager parts are often sacrificing their own need for nurturance and healing in service of the system, which they believe may fall apart without their influence. An example of a manager’s strategy would be compulsive people-pleasing to attempt to pull in positive regard and ensure that an exile vulnerable to criticism does not get triggered. Another example would be choosing not to go to a pool party to try to ensure an exile feeling body-shame does not get triggered. Given that the broader culture has values embedded within a patriarchal and heterosexist ideology that privileges cisgender individuals which may be reflected within the family of origin, the managers’ definition of “good” may contribute to the internal exiling process. I.e. if parts declare a gender different from the presenting biological sex of the individual, or espouse a same-sex attraction, managers may seek to keep their presentation out of awareness – often through shaming or depression. Manager parts can depress other parts seeking to come into consciousness resulting in a “flatness” in the system’s presentation. It is effortful to keep parts out of awareness and depression often has its roots in a depressing part. The most common tool of a manager part is the critical/shaming voice (the “should”). Usually these parts have learned that shaming is the appropriate response to “unwanted” parts’ behaviour. Typically young manager parts have internalised this from shaming parents. Shaming is endemic in our culture. Typically our parts that respond to the shaming manager feel beaten down – and it can be a challenge to hold the understanding that these critical parts are serving us with a positive intent. Yet when we get curious about these strategies the manager parts can share with us their concern, e.g. “If I didn’t shame you for being so bossy you’d have no friends”. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 2 Reactive Protectors - The Firefighters Firefighters show up when a vulnerable part (exile) has been triggered. This inevitably occurs in a world that is ripe with opportunities to break through the defenses and efforting of the wellintended managers. The firefighters sole concern is to provide comfort to the system and/or distract from the distress that is seeking to emerge. In so doing they change the state of the system. Much like firefighters in the external world, our inner heroes are summoned by the alarm set-off by the exiles distress. It is common to find a hierarchy of firefighter strategies, which begin with more mild approaches and escalate until the pain of the exiles has been appeased once again. Common firefighter strategies include: alcohol and, drug use, sexual risk-taking, rage, dissociation, watching porn, cutting, internet surfing, using food and suicide. When listened to from Self, we begin to hear the echoes of the exiles pain in the extremes of the firefighter strategy, and understand that they too are compelled into their role in an effort to (from their perspective) keep the system regulated in the face of emerging internal distress. Like managers, firefighters may also have started out as young parts in the system, perhaps using dissociation (the “daydreaming kid”) or rage (the “oppositional defiant” child). As they grow they have access to other avenues (alcohol, sex, drugs etc.). Because their behavior is often immediate and extreme they are generally disapproved of by, and polarized with, the managers. Manager parts want us to present well in the world and will often shame these parts internally and can be severely critical. When we are blended with a critical manager part we can feel both internal disgust (“How could I have done/said such a thing?”) as well as triggering the shame of an exile (“I’m a horrible person”). Many people come into therapy to deal with the ‘problem of’ the firefighter. It is often their manager parts who make the appointments with the therapist. Sadly, in traditional therapies, the therapist’s manager colludes with the client’s manager part and seeks to banish/fix/eliminate the firefighter behaviour. In such therapy, the beleaguered firefighter rarely gets to name its positive intent and allow us to know about the exile that it is protecting us from. They may show up so fast that we find ourselves asking “What just happened?”. In addition to their reactivity, when the baseline state of the system is distressing (e.g. dominated by a part feeling unsafe in the world) the firefighter behaviour to soothe/distract may become chronic. This is the root of addiction. When they are not in their protective roles these are the parts that may enjoy food, alcohol, sex, and a variety of playful and sensual experiences. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 3 Exiles These are the parts of us that hold distressing feelings and beliefs (burdens). They often take on their distress in response to events in childhood (neglect/abuse/bullying/teasing) and respond in self-referential ways, “The reason they are being unkind to me/not meeting my needs must be because there is something wrong with me; I must not be interesting/pretty/normal/smart enough, maybe it’s because I am unloveable. These distressing feelings and beliefs are held by a part who then gets exiled into a corner of the psyche so that the system can continue to function and thrive, leaving it frozen in the past. The exiled part wants to be heard and will seek to get out attention in the present by interpreting events through its lens. We can therefore become aware of exiles when we notice habitual responses to events wherein we feel bad about ourselves. e.g., “I didn’t get that job because I am such a loser”, “That person won’t want to date me because I am not good enough”, “My soufflé didn’t rise, I always mess things up”. Or we can infer their existence from protector behaviors, such as a manager part saying, “You better not apply for that promotion: what if you don’t get it?” (the “loser” part will get triggered) or a firefighter part insisting that we load up on alcohol at the office party after a colleague has looked at us disdainfully (and triggered “I’m a loser who now needs to be distracted from that pain”). Exiles’ presentation may also manifest as heaviness in the mind, body, or heart; communicating a deep and implicit misery much like that of a child who has been abandoned. Exiles desire to be able to release their burdensome beliefs and feelings which is why they seek our attention. These burdens are not innate- we are not born with them. They have been taken on by a part of the system and because they have been taken on they can also be released. The process of releasing the distress held by the exile is called “unburdening” and is achieved through internal compassionate witnessing, usually followed by a protocol that both facilitates the release of the distress and the internalisation of qualities, determined by the exiled part, that allow it to be at peace and in harmony with the rest of the system. Diagram 1. Example of one way to visually represent the organization of our parts and their interrelationship within the system. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 4 Self Self, often described as “highest self”, “best self”, “core Self”, or “true self” is present in all people and is often occluded by our parts. Self is characterized by certain qualities: • Compassion • Clarity • Calmness • Curiosity • Courage • Connectedness • Creativity • Confidence • Harmony • Healing Self is often described as a felt sense, an energy, rather than a thing and qualitatively different from the parts (although some parts have elements of Self, i.e. a parenting or caregiver part can present with many of the above qualities, and it will have an agenda). The only agenda of Self is the facilitation of greater harmony achieved through healing. If you imagine yourself at your best, perhaps on a beautiful summer’s day, lying under a tree with someone you care about, feeling grateful to be alive, then chances are in that moment you are experiencing a lot of Self energy. Self is sometimes described as best self or highest self. The concept of Self is the aspect of this model that makes it particularly unique. Many models talk about inner parts, but they do not refer to Self. Dick Schwartz discovered Self through working with clients and hearing them describe this “something different” that was somehow not the same as the parts and that they often described as “my self”. This self always seemed to show up with a compassionate voice, and with the ability to heal the inner world. Self is present at birth, exists in everyone, and can and should lead the system. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 5 Self is often described as Self energy, and this refers to the sense we have when we are experiencing more Self in our systems. For Self to lead it has to be embodied and when it is there is a noticeable difference in how the body feels. I experience a sense of being bigger than usual, as though my energy field has grown. There is a fluid feel that may have not been there while being blended with a part. E.g., I have an anxious part who shows up in my stomach and I feel a bowling ball is in there, and a protective part who shows up in a sense of pinched nose and raised eyebrows. When Self energy is flowing through me, most of my physical sensations recede and I become less conscious my body. Dick Schwartz talks about a sense of energy flowing through his body that makes a gentle vibration, your sense of more Self energy being present may be unique to you. One of the places I find that people get confused about Self is thinking that Self is a thing that you are either in or not in. When we think of Self as an energy it is easier to see it in terms of amount. How much Self energy is present is a much more useful question than “Am I/my client in Self”. When we are practicing we need to be monitoring how much Self-energy is available both in ourselves and in our clients. As you practice you will become aware of how you can notice Self energy in your system, it can feel like you at your very best. We all have places and people and things in our lives that elicit more Self energy, for example for some people it can be elicited by a piece of music, for others, by a walk in the woods, for others, the sound of water, for others a smell, playing with a pet, or doing something creative. You might consider that our parts are like clouds, taking up more or less space on any given day, some visible and some outside of our view. Self-energy, in this regard, may be thought as of the sky/universe holding up the clouds, something that always has been and always will be. This metaphor helps to communicate the nature of the Self, in that we do not cultivate Self energy (the clouds were always held in the sky, after all), rather we understand that Self is immanent and we work with parts to help them see that they are held and loved inside. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 6 Often therapists and clients will “try to get into Self” and this may lead to frustration because it can’t be forced. It is more of an experience of allowing, or of freeing up Self energy than one of trying. Freeing up Self energy is about paying enough attention to our parts and to have a good enough relationship with them to be able to ask them to soften or step back. Sometimes when we really want to have more Self energy to be able to sit with a client, and for whatever reason our own parts are activated, it is tempting to ask parts to step back in a forceful way. This generally leads to the opposite of what we are trying to achieve, as our managers try to get the other parts to step back and get on with being a good therapist. The “trying” from a partis effortful; connection is effortless. Most of us have a “good therapist” part who wants to do the best they can for our clients, and these parts will sometimes be doing the therapy. With a client who has plenty of Self energy and a system that is not traumatised, this can still work to a certain extent. These good therapist parts can often be “Self-like” parts. Parts who mimic Self and often think that they are Self. These Self-like parts are very hard to notice in ourselves and you will have the chance to practice looking out for them as we go on. They have qualities of self and can sometimes do good work, and the difference is that they will have an agenda other than connection. You may hear IFS therapists talking about being Self-led. Being Self-led is the way of being that is considered optimal in this model, and it essentially means that Self is making the decisions rather than the parts. Parts are talking to Self and trusting Self so that Self is able to hear from them all and make a decision based on being fully informed. Self has no power except for that granted by the parts, and then with Self in the lead, the parts are resources for Self Sometimes clients are convinced that they do not have a Self. In my experience this happens with clients who have many strong protectors, and those protectors can be committed to a belief that if they step back the system will collapse without them there running the show. Other times clients do not trust Self and there can be many reasons for this. In a particularly traumatised system Self may have been almost literally “beaten out” of the client. In such a system it is important to spend a lot of time appreciating and respecting the protectors and getting to know their concerns. The more Self energy we have available to us at any time, the more authentic we will be with others, and the easier it is to do therapy. When we are doing therapy with a lot Self energy, we are less likely to feel drained or tired after an intense session, than we are to feel energized. Self may be understood as both a number of qualities that we can and do embody, and an energy that is available to us. Just as in quantum physics we find the same phenomenon presenting as a wave and a particle; Self can be understood in this way. When we are working with clients we can consider we are co-creating a field of Self energy within which the requires healing can take place. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 7 Goals of the Model: 1. Self leadership. The more you attend to, appreciate and listen to your parts the more they will know that you (Self) exist, are available for them, and can be trusted to lead the system. Leading from Self results in a calmer, more confident and easier, less stressful way of being in the world. 2. Harmonising the System: Exiles have taken on distressing beliefs and feelings as a result of challenging external events, usually when young and without the presence of a trusted and supportive adult. Through the process of bringing Self to the exiles and inviting their stories through compassionate witnessing, it is as if the event now occurs with a trusted adult present who is able to witness the scene and intervene for the exile by either simply witnessing all that the exile wants to share, or by entering and changing the scene. This process allows for the information that had until this point been held by the exile (feelings/beliefs/stories) to become available to Self, and for the trauma of holding it alone in exile to be released from the system (unburdening). The exile may then take in whatever qualities will help it assume a preferred role (e.g. if it felt worthless it may take in confidence). After an exile has been unburdened the same triggers do not result in the same response, for example not getting the promotion is no longer wired to “I’m a loser”, if the belief about being a loser is no longer germane. Once an exiled part is unburdened the associated protectors may choose to relax their roles as there is no longer the distress present in the system to protect against. Protective parts may choose to keep their roles or to change them; they will no longer feel compelled into their specific actions by the distress of the exile. The resulting changes then include a greater adult response repertoire. If an exile holding shame has released its burden and no longer sits with the potential to be triggered, people-pleasing managers may choose to selectively use their skills but will not feel compelled to be present for every interaction. The disdainful look of a colleague may now be seen as being entirely about their critical system with no meaning for the recipient-and therefore no need to drink to distract from the distress: allowing the firefighter to relax. We can also note that it is also not necessarily the goal for parts to never take leadership in the system. In fact, once unburdened our parts can express their innate gifts and abilities that may make them great leaders in particular situations. The difference is that parts can take over or retreat in alliance with Self, and function for reasons that are not protective, but rather more indicative of their true nature. We all have a unique constellation of parts; they are ours to love and attend to and to help heal where necessary. You would not be you without them. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 8 How to do an IFS Session Part 1: The Self-to-Part Connection Your job as an IFS therapist is very simple: you hold as much Self-energy as possible, by asking your own parts to soften back and you facilitate the Self-to-part connection for your client so that their own Self energy can be available to heal whatever distress is being held within their system. You may wish to think of the session as a healing conversation between yourSelf and the client’s system. When Self is present compassion and curiousity arise naturally. Just as in the physical body when there is a cut the body knows how to heal itself, so does the psyche. In the physical body if the cut is a gash then we need to find a way to bring the skin close so that the body’s natural healing will weave the repair. We can do this because we know the body heals in this way. Similarly we now know how the psyche heals – so we facilitate the proximity of Self to the distressed part in order to allow for the healing to happen. We do this by getting permission to be a “parts detector” inviting the client to know when they are presenting from a part, vs. presenting with more Self energy. 1. Settle in to the session Take a couple of breaths, perhaps close your eyes and invite the client to do the same if they wish. Take the time to notice which parts of you are up and to invite your therapy managers (and whoever else might be up: “Did I lock my house?” “I wonder if she got that email yet?”) to step back as you embody more calm (Self energy). As mental health professionals we all have parts that come up around different clients. One client may elicit a desire to fix them, another a part that dislikes one of their presenting parts. We may have parts that feel intimidated by a certain client, or a part that sexualizes a particular client, or yet another that wants that client to be its friend. All of that makes sense and, as you become aware of whatever parts are present in anticipation of a particular client you can acknowledge them and ask them to soften back to allow you to be present for the work. All of your parts are welcome, and they are not required to be present for the session – that’s your job. If some of your parts seem to have a lot of energy around a particular client then you may want to spend time getting to know it outside of session. 2. Find a target part. The client may have a part that has been asking for attention. If the client is having difficulty finding a part seeking attention you may wish to check to see if it is okay to be doing the work, or if a part doesn’t want to. There may also be a blocking part. If there is a blocking part then focus on that as the target part. Invite the client to get to know this protective part. Sometimes manager parts believe they should present something to the therapist (often a people pleaser). Consider: is there a manager part saying another part (e.g. firefighter/lazy part) should be worked on? If so you may wish to work with the manager that may be distressed by the other part (i.e. wanting it to change somehow so that the manager’s life can be easier). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 9 You can also invite the client to reflect over the past week to see if there were times when they had a “big” reaction to something (anger/anxiety/self-criticism). Alternatively, invite the client to close their eyes and do a body scan (slowly move from the top of the head to the feet) looking for areas of tension, or heat, or anything else that grabs their attention. This may be a part presenting somatically. Once a part has been identified you can ask the client where they experience the part in or around the body – it helps to anchor the experience and enables the client to focus. For your first practice sessions please focus on protective parts – managers are easiest at this point: people-pleasers, controllers, figuring-it-out parts. If a vulnerable part does present (e.g. “I felt like a little kid who couldn’t do anything right last time I met with my parents) you can ask how the client coped. Their response will likely introduce you to a protective part, e.g. “I just agreed with them the whole time” or “I spaced out” or “I went for a long walk” or “As soon as I was alone I started watching porn”. 3. Check for Self-energy in the client Ask them how they feel towards the part. When they respond listen for what sounds/feels like Self energy (the aspects of Self we most often work with in the session are Curiousity and compassion). Listen for comments such as, “I feel warmly towards it”, “I’m wondering how it got to be that way”, “my heart is open to it” etc. We want there to be a “critical mass” of Self energy to move forward. If there is not then we will simply encounter more protector responses as the client’s self-like part takes the lead. Self-like parts may present in response to the questions as: • I want to help it (fixer) • I understand it (if it felt fully understood it would not still be presenting) • I feel sorry for it (pity) • I agree with it (ally/empathic part) • I just want to give it a hug (caregiver). Sometimes Self may offer comfort/a hug, but this usually occurs after a vulnerable part (exile) has shared a lot of its distress 4. Facilitating the Connection This module is entitled “Just Ask” to highlight the importance of both maintaining your own curiousity and inviting that of the client. When we ask parts about themselves from the place of genuine curiosity, as you might someone you like and want to get to know in the external world, they respond positively. This is the Self to part connection and in this module you will be practicing facilitating that connection from which everything else flows. “How do you feel towards that part?” IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 10 As mentionned above, this is the key question to establish the Self-to-Part Connection; “feel towards” is a connecting question (unlike feel about which invites a cognitive part to respond; describing the part but not connecting). This is an unusual question for someone not used to paying attention to their system and they may ask for clarification. It may be helpful to restate the question like this: “Well, you just heard a part of you saying that (e.g.) it hated its job. What happens for you on the inside when you hear that? How do you feel towards it?” OR “When it tells you that how do you want to respond?” OR “What just happened when I asked you to do that?” (A part may wish to declare how odd or weird this task is. If so, you can validate that part). Repeatedly asking this question may bring up parts in us: “They came here for therapy and all we are doing is asking this question”. Maybe a part of the therapist is concerned they may leave, they are not getting what they came for, they may get angry etc. It is helpful to be aware that each time you ask the question you are inviting the client to know a part that desires to be known. This is the first step in witnessing which will lead to the clearing of the distress taken on by the system that has resulted in parts in extreme places – either holding extreme distress (the exile) compelled to behave in extreme ways by the existence of the part holding the distress. If the client feels stuck at this point and it is early in the work, you may wish to coach them. E.g., “Imagine a friend of yours told you they hated their job. How would you respond?” Chances are they would be curious. If not, if they have a part saying, “They just need to deal with it” then switch tactics. You might want to add, “The job hours mean that your friend never gets to see his partner and their new baby, and he is worried his partner may leave” to see if a more caring response is elicited. If the client is adamant that a job is a job, and we should all be grateful to have one (or somesuch) then you may wish to explore the part holding this strong belief as the target part. Sometimes attending to parts inside can feel weird, or clients might think you are implying they have DID (formerly termed multiple personality disorder), or that you think they’re crazy; so, if they are experiencing difficulty you can ask them about that, or just name it as what “some people think” and/or name your own parts and what happened when you started “going inside”. Spend time ensuring that the client’s part is oriented to the client’s Self and not confusing the client’s Self with another part or another person. If the client reports that they don’t like the part, are indifferent towards it or any number of responses that don’t sound like curiousity or appreciation then you can be sure that a part has blended with the client and is responding. You may offer that back to the client and ask them to invite that part (indifferent/disliking) to soften back. Then ask them to return to the target part to see how they feel towards it now. If the indifferent/disliking part won’t budge it does not have to – you can then invite the client to focus in on that part and how they feel towards it. Once the client’s curiousity/warmth/appreciation is available you can strengthen the connection. The following questions help with that process: IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 11 • Is your curiousity available to you? • Is it okay to get to know this part? (If not stay with the concerned part) • Does it know you’re there? • It is aware that you are the age you are? Ask it to tell you… • Invite it to be aware of the year, show it aspects of your present life • How does it respond • What information does it have for you now that it has your attention? • How is it presenting that information to you? • Now it is aware of your presence how is it responding? • What role/job does it have in your system? • How long/at what age did it take on that role? • What was happening in the client’s life at that time that necessitated it taking on that role? • How does it feel about that role? • Hypothetically if it were possible to change its role in some way would it be interested in that possibility? • If it feels genuine thank it for letting you know about itself. If it does not feel genuine see if there is a part not wanting you to thank it for some reason • How does it respond to your appreciation? • (Optional) let it know you will return to it If the target part is an exile (often young and holding distressing feelings and/or beliefs and/or in a distressing scene) you may notice that the client has protective parts between their Self and the exile. These protective parts in the client are your greatest allies in the work. They care deeply for the exiled part and will only let self in when they are certain there is enough Self energy to ensure the part will not be harmed or subject to another part’s agenda. When the protective parts can sense the engaged kindness of Self they will allow the healing to happen. For these reasons we want to spend time with the protective parts getting to know them and thanking them for their efforts on the system’s behalf. Often these parts will simply soften back/stand aside when asked. For this module, however we do not want them to step aside; we want them to know Self appreciates them. If in your practice IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 12 session an exile “bursts through” (lots of sadness/fear/shame/misery presents close to the surface) please let it know that you and the client know it is there, and that it wants attention, and that the client is on their way. But first we have to determine that it is safe to get to know it. It is in this way that we prevent backlash – critical parts beating up the client post session because they were too vulnerable/unsafe etc. The process can look something like this: T: How do you feel towards the part? C: I want to get to know it but there is a fog between us T: Ask the fog how come it is there C: Okay, it did. Now there are a lot of distracting parts T: How do you feel towards the distracting parts? C: I don’t like them T: Uh-Huh. And the one that doesn’t like them? How do you feel towards that one? C: I get it T: Can you let it know that? While this may seem monotonous to some (therapist part) if this process is adhered to, at some point the natural, Self-led curiousity or compassion will emerge. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 13 Module 2 “What’s the Worry” Working with the Protective System IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 14 Working with Protectors Protective parts of the system are either the proactive manager parts or the reactive firefighter parts. Usually they are polarised but can, on occasion, work together. For example chronic use of drugs/alcohol may be indicative of firefighter (distracting) activity that began many years ago and has become so integral to the lifestyle that a manager part may see quitting as too disruptive and triggering of parts that feel like they “can’t cope”. More commonly though the managers do not approve of the firefighters and hold them in high judgement. The firefighters often respond to this judgement with resentment and/or anger. Hence the polarisation. Managers None of us would be where we are today without our manager parts. They are attentive, reasonable, concerned with social mores and want us to look good. Our managers plan events, get us places, figure stuff out, do our banking and manage other day-to-day aspects of our lives. To date they have been running the show and it is appropriate to show them some love and thank them for all of this. Managers enjoy their roles. However, when a manager feels compelled to drive the system in a particular way it can feel burdened by its role (e.g. chronic people-pleasing). Any sense of “I have to” (vs “I choose to”) speaks to a manager part working hard to ensure a part holding distress (exile) is not triggered. Nevertheless, in the absence of other options, the manager will continue to serve in this way. Fortunately we have another option now; Self is available to facilitate healing by rebalancing the system. Often the managers are suspicious of Self – from their perspective they’ve been taking care of everything for years, maybe decades, then suddenly Self shows up claiming it can and should lead. Managers are not likely to simply hand over the reigns – nor should they. It may not be safe and “Self” could just be another part as far as they are concerned. Appreciating Managers Self can, and does, truly appreciate the manager parts of the system in an unqualified way. When you ask a client how it feels towards a manager part, look for this unqualified appreciation. If you hear, “I like it but…” ask the “but” part to soften back so the self-led appreciation is available. When the client says, “I like it” (or something similar) invite them to find a way to let the manager know that. Once the Self-to-Manager connection has been established then the following questions may be helpful. You can ask the part directly (direct access) and it is better for the client’s Self to be communicating with the part. Bear in mind that depending on the answers it may be necessary to recheck the Self-to-part connection as information from a part can trigger other parts. A simple question like, “When it shares that with you how do you feel towards it?” Or “Do you still feel open to it?” Can help discern if there is still sufficient Self energy present to continue. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 15 If not, if for example the client says, “It’s hard to hear that” then you can invite the part that finds it hard to hear to go somewhere in the client’s system where it feels safe. You can ask the client: • • • • • • • • • • • Does that part know that you are there? Is it aware of your presence? (If not invite it to become aware of the client’s Self and/or invite the client’s Self to find a way to engage) How do you feel towards it? How long has that part been doing this (behaviour) or been in this role? When it started doing this (e.g. age 7) what was going on in its 7 year old world? I.e. what precipitated it taking this role Does this part know how old you (client) are? Ask it to tell you Can you let this part know how much you appreciate it taking this role? (Take time with this; the part really needs to feel how loved it is) What else does it want you to know about how it serves you? How does it feel about its role/job? Is it connected to another, more vulnerable part? Hypothetically if it did not do this what does it imagine might happen? What would be the consequences on the inside? (This will give us information about the exile) If it were possible to change anything about its role would it be interested in that possibility? We keep these last two questions theoretical to allow for the manager’s skepticism that change is possible. The manager does not need to believe it is possible; it just needs to be willing to allow for something different to occur. When managers whose behaviour is compelled by an exile’s distress are heard they will usually let you know that they are tired or that there is something they would like to change if they believed it were possible. Then we make the offer: • • We have a way now to help you to not be so tired, to not have to be on 24/7. If it were possible would you like that? Assuming you get a yes… In order for us to help you to not have to work so hard we need to get to know the one you are so protective of – would that be okay? (See list of common manager concerns and how to address them) Worth noting here is that many managers start out young, they model their behaviour on what they see their parents/caregivers doing or on what they are told they should be doing by their parents/caregivers. Managers determine that they should follow parental/adult directives to ensure that we are good people (which motivates us all). Their thinking is often the black and white perspective of a child and they learn to criticise parts that may result in disapproval because the absence of caring and love that occurs when the system is disapproved of/criticised/shamed can be intolerable. Often criticism triggers a part that worries or believes it is not okay, that there is something wrong with it. This is the source of shame which is endemic in our culture. Many manager activities are devoted to attempting to ensure that the part holding the shame (exile) does not get triggered and they will order our lives, where possible, around that goal. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 16 5. Get permission from the protective parts to get to know the target part. If a protective part will not soften back/step aside ensure that the part is oriented to the client in the present, to ensure that it is not confusing the client with another person or another part. You may want to ask the part to state the client’s age to the client to check the connection. If the part thinks the system is (say) still 10 years old, then this can be a shock so allow time for the part to assimilate the information. If the part is still unwilling to soften back, ask the client to find out what the concern may be. Address the concerns of the protectors until they are willing to allow the client to get to know the target part. It may help to remind the client to appreciate any protectors who are concerned about getting to know target part; they are serving the system in the best way they know how. Concerns of Protective Managers May include (but are not limited to): A. Flooding The part’s feelings may flood/hijack/overwhelm the system. Chances are that this has happened before and the protectors remember when the whole system was flooded with shame/fear/helplessness etc. Validating the protector’s concerns is important. Then it is helpful to provide them with information to allay their concerns: i) In the past, the only way the exile knew how to get attention was to hijack the system; what is different this time is that Self is both available and choosing to attend, which is what the part is seeking. ii) The target part can be informed that if it floods then Self will not be available as protectors will come up and it will not be heard iii) It can be assured that it does not need to flood for Self to get the degree of its distress through compassionate witnessing B. The Part will take over the System Similar to flooding, if a part wants to (e.g.) leave their partner there may be concerns that getting to know it means that it will take the lead. Remind the client that Self leads the system and the work is about getting to know the parts. No one part is invited to take over. Rather when they are known, decisions can be made that are more inclusive and result in less backlash from other parts. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 17 C. Insufficient Self energy If this is stated, then ask the client to check for any partially blended parts with an agenda other than connection and curiousity. Protective parts are your greatest ally in assessing the degree of Self-energy available D. Being Embarrassed or Ashamed This is another part and it can be invited to go elsewhere in the system. It does not need to be present to the Self/part dialogue if it finds it hard to witness. Acknowledge its discomfort and invite it to a space where it does not need to watch (and therefore feel embarrassed). If it feels it does need to stay ask it what would make it easier for it, e.g. being behind a shield, or in a protective bubble E. Rewriting the Dominant Narrative The concern here is from a part that has told the story that, for example, “I had a good childhood and my parents loved me”. If an exile is revealing information about an angry parent who was cruel and didn’t love it, then the worry may be that the life script may need to be revised. This concern can be addressed by reminding the client that this is only one part’s experience of the parent and, moreover it is one part’s experience of a parent’s part (in this case, likely a firefighter). Attending to this part does not invalidate the parts that did feel loved by the parent and had many happy times. If, however the protective part is still worried (for example about the disclosure of sexual abuse or incest) then it is important to thoroughly explore its concerns – often including significant grief over the loss of illusion. Protectors will have maintained the illusion for fear that the system “can’t handle” the truth. Self can hear the distress, clarity is a quality of Self, and attend to any grieving parts. F. Needing to Engage with others Differently A protective part may be worried that new information released into the system will necessitate a different way of engaging with others; possibly confronting a person who has transgressed against the client, and then bringing up parts who fear confrontation. The concerned part can be reassured that all we are doing is listening internally and no behavior changes need obtain from listening. If, as a result of listening to the information held by the exile, there is a desire from some parts to confront/adjust behaviours then that possibility is floated in the system and any and all stakeholders are invited to the “table” so that a self-led decision (i.e. one involving the least amount of internal distress or backlash) can be made. When protective parts soften back ask the client to thank them for permission to get to know the exile. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 18 6. Reassess the Self-to-Part Connection. Encourage the client to connect with the part through compassion and curiosity. Often it is helpful to ask where the part seems to be located in or around the body, then to focus in on that place. Watch out for the client getting blended with the target part, and if the client starts to show intense emotion ask the client if it is ok to be experiencing the feelings of the part. If the client is getting overwhelmed help them to remind the part that if it blends then there is no Self present and ask if it would be willing to hold onto its energy/emotions etc., then Self can be there too and be company for the part. The gender of a part may be different from the biological sex of the person so remember to refer to a part as “it” until the client uses a pronoun to refer to the part – if they do not use a pronoun then stay with “it”. Ask: “How do you feel towards that part?” 7. Facilitate Hearing the Story (Witnessing) Take as much time as the part needs to tell its story. Encourage the client to be with the part in the way that the part needed an adult at that time (if it is a child part) i.e. engaged, interested and compassionate (Self). Oftentimes the parts that are triggered present-day and sound like adults have been around for a long time. It can be helpful for the client task “How long have you been around?” or “When did you first start doing/feeling this?” Protectors often commence their strategies early on (e.g. a 6-year-old people-pleasing manager may decide that is the best strategy for ensuring a 5-year-old that has taken on the burden of worthlessness does not get triggered and flood the system). The strategy becomes habituated and generalized over time and a 48-year-old system may still be run (unconsciously) by a well-intentioned, and often exhausted, child part that has figured out how to be in the world to the best of its ability. Unfortunately, its strategy does not allow for the honest expression of parts that do not always want to people-please. As these parts’ needs get exiled they will repeatedly get triggered until their energies can no longer be contained. It is likely that at that point a firefighter will emerge, using typical distracting or comforting strategies (anger/food/alcohol/sleep etc.) until the exiled part, (“What about my needs?” )has receded again to the corner of the psyche to which it has been consigned. As the exiled part begins to release information to Self (burdensome beliefs/feeling etc.) the system can experience this process as very intense: powerful feelings/revelations are accompanied by a concentrated focus on the part. Often there is a dance of protectors coming in to both give Self a break and allow for the information to be assimilated within the system (“Oh, this part holds the experience that Dad never really loved us”) as other parts respond. This may be reported as “The part has IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 19 gone away” or “I’ve lost the connection” or “I’m feeling blank towards it.” Encourage the client to appreciate the protector for coming in to provide some relief, and then when the system is ready ask it to withdraw again so Self can re-engage with the exile. 8. Retrieval of the part This is not always necessary and can be helpful if a part is in a distressing scene. Invite the part to a safe place out of the scene that it is stuck in and from there invite it to share its distress. It may wish to come to the present with you, or go to a place where it has felt safe in the past. It may experience relief to be out of the threatening environment – do not confuse this with the release of unburdening: it is likely still holding distress as yet unwitnessed. 9. The Redo Again, this step intervention is optional and gives you a different way to do the work. If a part is in a distressing scene, for example being abused by an adult or feeling helpless as it is witnessing someone being hurt, then you can invite the client’s adult Self to enter the scene if the exile would like that. If the client has a lot of Self energy they will be able to courageously engage with the abusive adult in the scene and change the outcome. For example the client’s Self may grasp the hand of a parent hitting a child, or stop an adult from kicking the child’s pet. The client’s adult Self can be encouraged to be the protector and advocate for the exile that was not available at the time. Ask how the scene is playing out in the redo. Typically the abusing adult will back off, perhaps sulkily or otherwise reluctantly, but it will no longer be perpetrating. The exile then does not take on the burden and may not require further interventions, other than to invite it to leave the scene and go where it would prefer to be now; with whatever qualities it can now claim. 10. Helping the part to Unburden More typically we invite the part to be heard in terms f the distressing feelings and belefs it has been holding. After the part has been fully heard we can invite it to release its distress. Ask the client to keep checking, “Is there more it needs to tell you?”, “Is there anything else?” And then check the Self-to-part connection one final time: “Has the part told you everything and does the part feel like you really get it?” If the answer is positive, then proceed to the unburdening. Have the client ask the part, “If it were possible for you to not have to carry all these burdens would you be interested in that possibility?” The question is phrased in the conditional tense as it is not necessary for a part to believe it is possible, they often don’t, only to affirm interest. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 20 At this point the part may show concerns (rarely) about giving up the burdens: it may believe it will cease to exist. Reassuring it that it existed before it took on the current role (even though it has been so long that it doesn’t remember) can be helpful. Also, the guarantee that it will not disappear (using your own Self-led confidence – parts cannot disappear) can allow the work to proceed. When it is ready, invite the part to take everything that it has shared and release it in whatever way it chooses to Air, Fire, Water, Earth, Light, or to anything else in such a way that the burden will never return to it: The part no longer needs to hold the burden because Self has been able to witness it. 11. Returning to Wholeness When the burden has gone, invite the part to check its body to see if it feels clear or if there is still something there that doesn’t belong to it. If there is still a burden invite it to name and release that too. When it reports that it feels clear invite it to take in whatever it needs for itself to be able to move into the future. Usually a part will take in qualities that were not available to it when it took on the burdens – such as confidence, self-worth, likeability. Young parts may sometimes take in bubbles or pink… they know what they need. Be alert to the possibility that a manager part might want to suggest what the part might need and ask it to step back if so. It doesn’t happen often and when it does it feels a bit “agenda-like”. 12. The New Configuration When the part feels complete ask it where it would like to settle and how it would like to be in relation to the client. It is helpful to offer a menu. I usually say, “It can age, hang out with other parts, go off and have adventures, become embodied, act as an advisor, live in your heart…” Once it has settled, invite the protectors who were concerned about the client getting to know this part to be with the part and Self, so that they can see that the part is now safe. Invite the protectors to name any responses they may have to the new configuration. They may choose to modify or change their role in the system now that their habituated role is no longer compelled by the distress of the exiled part, and they may have burdens to release (such as “having to always monitor contact with other people for criticism”. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 21 12. Checking in Ask the client for an agreement that they will check in with part every day for 21 days to make sure that the burden stays gone. Ask them to tell you when and how they will do this. If they check in and the part has picked up the burden again, they can do the unburdening again. After about 21 days the new configuration becomes cemented. Ask if other parts may get in the way of checking in. 13. Wrapping Up Thank all the parts who stepped aside, allowed the work, unburdened etc. and ask if there are any parts with comments, concerns or questions about the work. A common question is, “Will this stay”. The answer is that there are 3 conditions under which the unburdening may need to be repeated: 1. The part has more to reveal about its burdens 2. There was not sufficient self-energy present and a manager took the lead 3. Events occur in the client’s life which mirror the original taking on of the burden during the 3-week period post-unburdening (E.g. if the part took on shame as its Dad was screaming at it and the client encounters an angry boss screaming at him/her then the burdens may return). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 22 In Summary: 1. Settle in to the session 2. Find a target part 3. Check for Self-energy in the client 4. Ask protective parts to unblend 5. Get permission from the protective parts to get to know the target part a. Address concerns 6. Reassess self-to-part connection 7. Facilitate heating the story (witnessing) 8. (Optional) Retrieve the part 9. (Optional) Redo the scene 10. Help the part to unburden 11. Return to wholeness 12. The new configuration 13. Wrap up IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 23 Firefighters Our firefighters protect us in a different and equally important way. Because our society prizes managers there is often a lot of judgement both externally and internally towards them. Our internal managers in particular tend to be polarised with the firefighters that make us look bad. The drinking part that is “out of hand” at the party, the chocolate-lover, the TV-binger, the extreme gamer, the stoner part, the sex binger, the cutter… much of the noise in our psyche is from these polarised parts: “You do – name behaviour – too much” says the critical manager; “I have every right to…” says the beleaguered firefighter. Simultaneously it seems we nonetheless find ways to meet the firefighter’s needs. Alcohol use is celebrated in our culture, many stories start with, “I was so drunk…” ; Las Vegas might be seen as firefighter central, the gaming and porn industries continue to thrive. Many firefighter activities, of course, are things we like or need to do. We need to eat, we like to have sex, drinking can be fun, gambling a thrill. It is important to be aware of our managers that might want to condemn a behaviour, or label it as firefighter activity when it may simply be a part seeking to present itself in a way that other parts may get concerned about. It is not uncommon in therapy for a client’s blended manager to bring the client into therapy to “fix” the drinking/drugging/eating problem. This may trigger the therapist’s manager into agreeing and colluding with the client’s manager; further demonising the misunderstood firefighter and naming its behaviour as the “problem”. A helpful way to determine if a protector’s behaviour (manager or firefighter) is connected to an exile is to see if it feels compelled to do what it does. If a part has to e.g. people-please, present itself deferentially, look important, then it is a operating as a manager protecting an exile. If we ask it the hypothetical question, “If you did not do this what do you think might happen, or happen internally?” It will be able to tell us of the negative consequences. However, if it is a part that just likes making people happy, or believes it is important to not take up too much space in consideration of others and/or enjoys presenting its leadership skills with confidence then it is just a manager doing what it likes/loves. Similarly if it is a part that enjoys getting high with its friends as it feels a deeper connection to them, likes the thrill of the slot machines, gets excited about reaching the next level of the game but does not feel a need to do this repeatedly then it is likely a part having fun; not compelled into its actions. The above parts may still be subject to internal criticism (manager criticising manager or manager criticising “fun part”) in which case we work with the polarity. Firefighters help us by responding immediately to the threat of exile overwhelm. When an exiled part gets triggered it is likely to flood us with its shame, and/or its terror, and/or its overwhelming sadness or whatever else it may be carrying. When this has happened in the past it may have resulted in us being unsafe and unsupported – you only have to look at a toddler having a tantrum to recognise how intense emotional overwhelm can be. The firefighter’s response is to change the state of the system as rapidly as possible by providing either comfort to, or distraction from the exile. When you consider the list of firefighter activities you can see this is their positive intent, no matter how extreme the behaviour may appear. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 24 Many people find it more difficult to bring the appreciative energy of Self to the firefighters as our lead managers may determine it is not safe to “encourage” them and be reluctant to soften back. It can be helpful to let the managers know we are appreciating the intent of the firefighter if not the behaviour. If manager parts are still reluctant to allow the client’s Self to get to know the firefighter then we can ask the manager part how long it has been trying to control/deal with the firefighter part’s behaviour and how much success it feels it has had with its strategies. When the manager part is able to admit that it has not been as successful as it would like then we can ask it if it would consider allowing Self to try something different – with the understanding that the manager can step in any time if it has concerns. Once we have access to the firefighter the questions are very similar to the ones we ask the manager parts: • • • • • • • • • • Does that part know that you are there? Is it aware of your presence? (If not invite it to become aware of the client’s Self and/or invite the client’s Self to find a way to engage) How do you feel towards it? How long has that part been doing this (behaviour) or been in this role? When it started doing this (e.g. age 7) what was going on in its 7 year old world? I.e. what precipitated it taking this role (NB often a firefighter may have used a different behaviour earlier in life, e.g rage or food, later replacing it with something like sex bingeing or drugs as they became available – they will often tell you this) Does this part know how old you (client) are? Ask it to tell you Can you let this part know how much you appreciate it taking this role? (Take time with this; the part really needs to feel how loved it is) Is it connected to another, more vulnerable part? How does it feel about its role/job? Hypothetically if it did not do this what does it imagine might happen? What would be the consequences on the inside? (This will give us information about the exile) If it were possible to change anything about its role would it be interested in that possibility? Firefighter hierarchy At the top of the list is the actively suicidal part. If this one is present it is important to attend to it first as it can scare other parts. As mentioned earlier, it can be a challenge for the client’s managers to step aside enough to allow the Self of the client to appreciate the actively suicidal part so I will generally work with direct access and check that what is being revealed all makes sense to the client. The interview looks something like this: Therapist: Client: T: C: T: FF: So, suicide has been on your mind a lot lately and you have a plan now right? Yes Okay. Would it be okay if I spoke to that suicidal part directly? Sure Thank you. So, you are the part of John/Jane that is planning the suicide right? Yes IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 25 T: Okay. So my guess is that the reason you are doing that is because there is so much pain in the system this is the only way to deal with it – is that right? FF: Yes (At this point you could check with the client, “Does that make sense to you” – or at any point during the interview) T: Okay, I get that. I also imagine that you are aware of the many attempts to deal with the pain that have not helped, right? (Depending on what you know about the client’s history you may wish to name them – rehab, repeated engagement in therapy that has not helped long-term, cutting, long-term drug use etc) FF: That’s right, yes. T: (Option) Can you tell me what some of them are? FF: Sure, (describes everything that has not helped with, e.g. chronic shame) T: Okay, so it sounds like nothing has helped, is that right? FF: Yes T: Well no wonder you’ve come to this conclusion about how to end the pain. And let me ask you, it it were possible to shift that pain, would you still need to be so strong? FF: I don’t believe it is possible T: Yeah, I get that. I’m not asking you to believe it. I’m asking about if it were possible. FF: Well yeah, I guess. If the pain wasn’t there then I wouldn’t need to do this but I tell you, I don’t think it’s possible. T: Sure, that makes sense to me given all that (John/Jane) has been through. So how about this. I know if you give me (3/6/10 – whatever maker sense to you as therapist) sessions I can shift some of this pain. FF: I don’t buy it, even if you do. T: Like I said, I’m not asking you to buy into it, I am asking your permission. T: (Optional) How long has this pain been present? FF: Forever T: So would three weeks make that much difference? And if I’m wrong and/or misguided then you are very welcome to return to your strategy. How does that sound? What if we actually can shift some of that pain? FF: Okay, you’ve got (3/6/10) weeks. T: Thank you so much. So does that mean you won’t take action until we’ve reviewed what we’re doing? FF: Yes T: Great. Thank you so much. T: (to client) How was that to hear? (We want to see if the client can now recognise the positive intent of the FF) T: Any part having a response to that conversation? T: Please thank your concerned manager for allowing us to talk to the suicidal part; it was showing a lot of trust in you, and me. C: It says you’re welcome IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 26 When working with other firefighters (cutters, dissociators, ragers, drinkers, druggers, food/sex parts) the principle is the same: ensure that they are loved and respected for their intent – ideally by the client’s Self. When this occurs they are likely to allow access to the exile. The manager parts care about the exile and the system by trying to ensure it doesn’t get triggered; the firefighter by distracting when it does get triggered. When both are genuinely appreciated and invited to be aware that something new may be possible that meets all the parts needs (an exile no longer holding distress resulting in these protectors being finally able to stand down) they will be supportive of Self’s connection to the exile. Firefighter behaviour can become chronic (as we see in what we call addictive behaviour). For example a system with parts holding significant anxiety (from, for example, a childhood where the family of origin did not feel ever feel safe) may have a firefighter that can tolerate the stress of the day until the drink or drug of choice or food activity or porn use can be engaged in later in the day. Also a particular behaviour may be engaged in by a manager or a firefighter. A manager part may be restricting food in order to control the system an d prevent a part feeling fat and unattractive from being triggered. Or the fat/unattractive part may be in a constant state of agitation and so a firefighter is restricting food to ensure the exile does not flood. You can determine the role of the part simply by asking. Sometimes manager parts are supportive of firefighter strategies. If a part feels weak and threatened a firefighter might feel compelled to workout 4 or 5 hours per day – at the expense of other areas of the client’s life. Since a gym body is valued by many as corresponding to the cultural perception of beauty, and the system may receive compliments, “Wow – you look great! Been working out?”, the manager may support this compulsive behaviour because it makes the client “look good” and staves off criticism. Whilst these distinctions are helpful in identifying the role of the part, we do not need to get caught up in categorising. Remember: all you need to do is hold your curiousity about a part (and invite the client to do the same) and it will let us know about its role in the system. The key distinction about how the parts serve is that protector parts have strategies; exiled parts serve by holding the distressing thoughts and/or feelings. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 27 Exiles When the protective parts acknowledge that there is a sufficient amount of Self energy available to safely allow the client to approach the exiled part we can invite specific questions that will help the client to witness the distress being held by the exiled part. Occasionally a system will present with an exiled part right away. If this happens check to see if there is a compliant part in the client that believes this is what the therapist requires. If present, this part may be overriding others concerned about safety and there will be backlash in the client’s system after the session. Backlash occurs when the work has gone to fast for the comfort level of the protective system and parts may punish the client and/or the therapist. Therefore if an exiled part is presenting it is helpful to let it know we will get to it – and to ask the client if there are any parts concerned about us getting to know it right now. Then double-check – reminding all parts that they are welcome. Generally speaking as an exile presents information about its distress, the client is able to hear it, then the connection may not be as clear. This usually means that a protective part has come between the exile (target part) and the client’s Self. The other possibility is that the client has a partially blended part with an agenda for getting to know the exile (e.g. to get rid of it, or fix it, or figure it out). The exile(s) and protective parts often dance in and out as the protectors help titrate the information held by the exile (memory of events, affect, body sensations, distressing beliefs) in order to ensure the client does not become overwhelmed. Exiles and protectors are often “frozen in time”, unaware of the age of the client and the current year. Orienting the parts to the present day is important. Just as you would ask any distressed child in the outside world why it was so upset, we do the same internally. Back when the distressing event or series of events occurred that resulted in the exile becoming burdened, the only resources the system had were internal. So we commonly hear minimising parts that tried to insist, “It’s not that bad”, reassuring protectors, “We don’t need to go there”, resigned protectors “That’s just how it is”, protectors that regard hope as a liability (because in the past it has resulted in repeated crushing disappointment and/or despair) and others that appear as we begin to connect with the exile. When these protective parts are updated and aware of how much Self energy is now available they may be willing to allow the Self to Exile connection. Part of how Self facilitates the healing in the system is by being present to compassionately witness the event(s) that resulted in the part getting stuck and holding the burden. It is as if there had been a supportive and compassionate adult available for the kid at the time – if there had been then the burden would not have been taken on. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 28 Questions when working with an Exile: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Does that part know that you are there? Is it aware of your presence? (If not invite it to become aware of the client’s Self and/or invite the client’s Self to find a way to engage) How do you feel towards it? How is it presenting itself to you? (Parts may present any way they choose: visually, aurally, in a “sensing” intuiting mode, through body sensations Does this part know how old you (client) are? Ask it to tell you What does it need you to know about itself? Are you clear on what it is showing/presenting to you? o If not, let it know and ask if it could present in a way that helps you to become more clear o Or check to see if there is a part between the client’s Self and the exile: if so, simply ask it to step aside or soften back. If it will not do so then ask it about its concern and address the concern (see common manager concerns) How do you feel towards it? Keep checking the Self to Exile connection Can you let this part know that you get how hard it has been/how much pain it is holding? What else does it want you to know about what it has been holding for you? Is there any more? Does it feel like you’re getting it in the way it needs you to get it? Is there any more? When there is no more information and the part has declared that it feels like Self gets it in the way it needs, then we can make the offer as follows: If it were possible for this part to not have to hold all of that distress/unhappiness/misery, would it be interested in that possibility? Remember, the part does not need to believe it is possible, only to express the interest or desire If the exile answers in the affirmative then we can proceed to facilitate its release of the burdens now that it has been witnessed. Further questions are: • • • • • What would it like to release all that to? Earth, Fire, Air, Water, light or anything else? (To client) let the part know that once released it never needs to take these burdens on again. Please let me know when the release is all done Now instruct the client to ask it to check its body one last time to see if it feels clear or if there is still something there that doesn’t belong to it. If there is more invite it to be realised. If all the burden has been released and the part feels clear instruct the client to invite the part to now take in what it needs for itself: usually qualities and accurate beliefs – what is true for it The part may now want to choose where. It will “settle” now. It may be helpful to provide a range of options: it could age, become fully embodied, live in the client’s heart, go off and have adventures or stay where it is in its unburdened form IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 29 After an exiled part has been unburdened remember to invite in the protectors that have been connected to it to see how they feel about the transformation and their subsequent rifle. They may choose a different role or to work less hard – they may also need time to decide. It is also a good idea to think the parts that stepped aside in session to allow the work. They can be thanked for their willingness to trust and invited to notice that nothing catastrophic has happened – quite the opposite. Shame – A Core Exile Maybe the most toxic burden, the feeling is as if you are not valued or included. When this occurs in a very young part it may be linked to survival fear: it becomes imperative to be valued and young protectors quickly figure out how to do this – hence the birth of the compelled people-pleaser, the perfectionist etc. Shame is a multi-part phenomenon. Usually an exile part took in a message that you were not valued, sinful, bad, incompetent etc. Then the critic that tries to manage that by shaming as the parents did. Then, often more firefighters or managers come in various ways, perhaps to distract us, preoccupy us, or tell us we are not bad - so we don’t feel that shame. The actions of those protectors may trigger those around us, who then criticise us, fueling the critic, which goes to the heart of the exile who then feels worse, leading to more protector parts doing their thing. This can easily become a cycle. This is why we commonly see the socially sanctioned protectors taking the lead trying to ensure the exile does not get triggered. The sense of being worthless comes into us from -Shaming words -Neglect -Being hurt (children always feel it was their fault that they were treated that way). Shame is used to get children to behave. It is highly effective short term, because kids will do almost anything to avoid it. Our inner critics, also go after our own children in the same way, believing it is. necessary. A note on non-burdened Exiles Occasionally you may encounter a part that has never been burdened but nonetheless exiled. Usually these parts have qualities that were not safe to manifest in the family of origin, e.g. joy in the presence of a parent blended with bitter, mean parts or confidence in a family that has a parent easily triggered into jealousy. In these instances the protective parts may hide the part so it is not at risk.When these parts are revealed they may simply need to be updated in order to take their place in the system: “It is safe to come out and be known now.” These parts generally hold great gifts for the client and it can be very moving when they are finally able to be integrated in the system. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 30 Special Considerations: Updating & The Impact of the Psychoeducational Intervention Parts are often frozen in time and engaging in habituated behaviours long after the precipitating situation and the associated players have passed. For example, it may have been necessary to always present in a self-effacing way in the family of origin to prevent triggering a violent and/or rageful part in a parent. The parts living in this situation may not know that the system has aged and is now adult; and that the parent is no longer around. Consequently the protective part presenting in a self-effacing way may take the lead in all social engagements – to the detriment of parts that would like to present differently. Sometimes the intervention of updating a part can result in it spontaneously changing its role in the system. Similarly a psychoeducational intervention (such as informing a parentified child part that it was never really her job to take care of her parents) can lead the part to happily abandon its role. It can be a surprise to hear – and a welcome one. This intervention can come from the therapist (direct access) or the client’s Self. The spontaneous releasing of roles, however, is the exception – by far – rather than the norm. If we update a part and it nonetheless insists on its role then we need to get curious about how come it is insisting on that (it will be referencing an exile). Similarly if an intervention like the above to the parentified child is met with “No, I do have to do this” then, again, find out more about the part. We can hold out the possibility that updating and psychoeducational interventions may be sufficient, and sometimes they are. But when not then abandon any expectation and come back to curiousity: we never want to get into a “parts war”. Direct Access If a client is fully blended with a part and it is hard for them to access their Self energy then you may wish to move to direct access (therapist talking to a blended part of the client) to ask the part that hates its job what it has to say. Shifting to direct access can be implicit or explicit, in other words we may ask the clinet, “can I speak directly with the part of you that hates its job?” or we may begin speaking directly to the part without naming the shift. In direct access, we ask many of the same questions we would invite our client’s Self to ask their parts, the difference is that our Self is now directly in connection to the clients part. Some questions during direct access here might sound like: “[Part that hates its job], what do you say/do for [client]?” “What are you afraid would happen if you stopped doing [job]?” “How old are you?” “Who do you see when you look at [client]/How old do you think [client] is?” After hearing it for a while you may wish to reflect back to the client, “Seems like that part of you has been doing this job for awhile, and that it is really tired. How is it to hear that?” or “did you just hear all of that [clients Self]?” These last question re-invite the Self-to-part connection to occur [unblending], as the Self has been able to hear from this part and extend towards it compassion or curiousity. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 31 Module 3 “Who’s Here?” IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 32 Therapist Parts The focus for this module is to become aware of the parts of you that have, to date taken the lead in your therapy sessions. Many of these are hard-working manager parts that have learned other models and have taken on beliefs about the work. It can be hard for those manager parts to “retire” and they may have concerns about not participating in the work. The more you can get to know them, love them, let them know that you are now available to do the work, the more they will be willing to soften back in session. You can also invite them to be present in an observing role. In addition to these well-intentioned therapist parts we all carry exiles that can get triggered in session and therefore we have managers and firefighters that can also enter the session. Below is an excerpt from peer-reviewed study from Australia in 2009. A qualitative survey was designed to reflect the questions frequently asked by prospective students seeking information on a career in the psychotherapy and counselling field. Open-ended questions sought to tap into personal experiences and illustrate opinions that could be drawn upon later to identify important themes. Surveys were administered to a representative of key training organisations in Australia. Becoming a psychotherapist or counsellor: A survey of psychotherapy and counselling trainers. Table 6. Respondents’ views on factors to reflect on prior to entry to the field Belief Statement Requires a willingness to explore yourself before working with others. The field is emotionally demanding, personally challenging and hard work. Requires a high level of responsibility. Not all people who seek help want to change and it is hard to measure success. Can have an impact on your own life and family. Can get a skewed view of humanity. The field is not necessarily financially rewarding. Be aware that counselling or psychotherapy training should not be used as a method to solve or avoid your own problems. Be aware of wanting to rescue others from the ‘perils of life’, to solve, ‘help’ or ‘fix’ people’s problems, or a personal need to be needed. Counselling and psychotherapy is not about being an expert or ‘all knowing’, or having power or influence over others. IFSCA Course Manual Frequency of category response (N=37) 17 Percentage of respondents 45.9% 17 45.9% 17 17 45.9% 45.9% 17 45.9% 17 15 45.9% 40.5% 14 37.8% 13 35.1% 11 29.7% www.IFSCA.ca 33 You may notice some of your own therapist parts as you look at this table, if so you may wish to take the time to say “Hi” to them, get to know them, get a feel for them in your body. Does a “fix it” part have you leaning forward in your chair? Does a “need to be needed” part have you nodding repeatedly and holding fixed eye contact to show that you are attuned? Is a part telling you the work is not necessarily financially rewarding determining your fee? For an IFS therapist it is essential to be aware of the parts that come up and may want to run the session: they will make it more difficult for your Self-led parts detector to be present. The faster you can recognize them, the easier it becomes to ask them to soften back so that you can stay focused and curious. Parts that may be connected to an exile (“need to be needed”, “personally challenging”) may become the focus of some personal work. Therapist Managers As always, our managers are there to protect our own systems, and all of the typical ones we see below in therapists are trying to protect us from something that might happen in the future. They can present as: 1. Wanting to appear a certain way to the client (or supervisor when we are in the student role, or colleague in peer supervision) e.g. knowledgable, organized; brilliant; effective; kind; empathic; “nice”. These managers can be caught up in people pleasing or needing to be seen as irreplaceable, or the best. (These parts believe that if we show up looking however they think we should look, then no-one will perceive the parts of us who might feel stupid, inadequate, disorganized, ineffective, unkind, etc.) 2. Wanting to see themselves as effective. These parts look to the clients to show fast and clear improvement and can get frustrated when clients move at their own pace (which can be very slow), and can also get resentful when clients do not show much improvement. (These managers are protecting against parts who may feel that we are not adequate as therapists in some way) 3. Caregiver managers who get caught up in needing to be the Self for the client rather than recognizing that their clients have their own access to Self and only need us to facilitate the connection. These parts can also have a hard time recognizing when a client has his/her own caregiver part up rather than Self. (These managers are often protecting against triggering a part who does not feel useful or needed by clients) 4. Critical managers who tell the therapist that they don’t know what they are doing, should get a job doing something entirely different and should send the client to a “real” therapist. (Our critical managers do not generally feel as if they are protecting us, and yet when we spend the time with them to find out what is going on for them, they will often say things like “if you recognized that you are not very good at this and got an entirely different job then you could feel good about yourself”). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 34 5. Critical managers who listen to a client’s managers talk about a FF activity that resembles one of the therapist’s own FF activities (e.g., your client is talking about how frustrated they are that they cannot seem to stop eating a pint of ice cream every evening, and the therapist has his/her own little evening snack attack FF). These managers criticize the therapist about it (“How can you possibly help this person when you can’t stop eating a packet of Oreos every night?”) Again it may be harder to see the protection of this sort of manager, and again, when we spend time with the parts, they typically want you to be more in control (so you don’t feel fat etc.) 6. Parts who try to control the clients FFs when a person has, for example, a suicidal part up. (These managers are often protecting the therapist from possible harm from a law suit or other disciplinary action, and are typically not trusting that the client has access to Self energy). 7. Parts who have pathologising way of looking at clients and start telling the therapist that this person is way more damaged than therapy can handle. This type of manager is also not recognizing that the client has access to Self energy. (This type is typically protecting parts of the therapist who feel inadequate/incompetent.) 8. Problem solving parts who want to interpret and make suggestions. (These parts come in variety of shapes and sizes…sometimes they are excited parts who want to share their ideas, and sometimes they are managers who do not believe that the client has ideas of his/her own, and may be protecting against an exile in the therapist who is afraid of not doing something that the client may need) 9. Eager parts who push the model, and rush to get to an exile. (These again can be excited parts, and they have an agenda that is a lot more rushed than the patient way that Self shows up. 10. Various other Self-like parts who have many of the qualities of Self. They are hard to spot at first, and it usually takes someone else to spot them for us. If you notice that you have many qualities of Self, but are: very focused on the path the client is taking; on an exile hunt; noticing that your curiosity looks more like the kind of a scientist looking down a microscope; in a hurry to get to the “meat’ of the session etc, then this is one of your Self-like parts. We all have them. Therapists are particularly full of them as we are so well trained in a whole bunch of skills that look like Self. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 35 Therapist Firefighters Just like our managers, the Firefighters are there to protect our own systems, and all of the typical ones we see below in therapists are trying to protect us from noticing an exile that has shown up in ourselves: 1. Angry parts who blame the client for whatever is being triggered in ourselves, and feel burdened by the client. 2. Voyeuristic parts who get a dopamine fix from clients stories and find ourselves wanting to know all the details. 3. Love or sex starved parts who get crushes on clients. 4. Defensive parts who protect the ones who feel inadequate in the face of client dissatisfaction of any sort. 5. Parts who take the therapist out during session and start fantasizing about beach holidays or what’s for dinner tonight, or going shopping etc. These parts can show up as boredom, hoping the client will cancel, losing concentration. (These may show up as a response to an overworking manager who works so hard that the therapist does not attend to their own needs.) Therapist Exiles 1. Hurt parts who have similar stories and have not done their own unburdening yet. 2. Scared or anxious parts who are triggered by client’s FF. 3. “Inadequate” parts who believe the managers who tell us we do not know what we are doing. You may choose to give your clients permission to be a parts detector around you after you have established the therapeutic alliance. The reason for this is that the client will sometimes see your parts before you do, and they will not do their work if they experience your parts as getting in the way. IFS therapists handle this issue in different ways, for example, some do not mention it until a client mentions something getting in their way, e.g., client says “I don’t feel as if you are really listening”, and therapist says “Oh let me take a moment and see if I have something getting in the way”. Some IFS therapists give clients permission before this happens to normalize it. We suggest that you check with your parts and do what works for your system. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 36 Multiplicity and Internal Family Systems Therapy – A New Paradigm? by Derek Scott (This article was originally published in “Psychologica” – the magazine of the OAMHP – Ontario Association of Mental Health Professionals) Since becoming acquainted with Kuhn’s (1962) concept of a paradigm shift I have wondered how this might apply to the field of counselling and therapy (and therefore myself as a therapist). This paper explores the emerging interest in multiplicity as a model for the personality and some of its implications for clinical practice. Kuhn (1962) argues that change in scientific thinking occurs as a “series of peaceful interludes punctuated by intellectually violent revolutions," and in those revolutions "one conceptual world view is replaced by another" (p. 10). The “cognitive revolution” (“Cognitive revolution,” 2011) of the 1950’s may be seen as a shift that turned much of our understanding on its head, relocating the ‘legitimate’ field of therapeutic enquiry from behaviour to cognition. As we enter the second decade of this millennium my curiosity is piqued by the “discursive explosion in recent years around the concept of ‘identity,’ within a variety of disciplinary areas, all of them, in one way or another critical of the notion of an integral and unified identity” (Chandella 2008, p. 61). Could this be the groundswell of a revolution in the social sciences? And if so what are the implications for our work? Jackson (1981, p. 86) informs us that “long before Freud, monistic definitions of self were being supplanted by hypotheses of dipsychism (dual selves) and polypsychism (multiple selves).” Many in the field of counselling and psychotherapy regard object relations theory, formally developed by Ronald Fairbairn based on earlier thinking by Freud,as the bedrock of counselling and IFSCA Course Manual psychotherapy. The theory describes how we internalize objects as mental constructs with which we form relationships. Generally, the theory has been interpreted to refer to a single subject cathecting multiple objects and then internalizing the relationships. Leowald (1962) argues however that internalization may be understood as “certain processes of transformation by which relationships and interactions between the psychic apparatus and the environment are changed into inner relationships and interactions…this is the process by which internal objects are constituted” (as cited by Kauffman, in Doka 2002, p. 73).So object relations may refer not simply to one subject engaging with multiple objects, but multiple internal relationships with multiple internal subjects. Howell (2008) supports this view, stating that “an internalized object must include the assumption of an internalized object relationship (in which) … both the selfcomponent and the object component have subjectivity” which inevitably leads us to “conceptualizing a multiple self as internalizing relationships” (p. 42). How does this shift in the view of self inform our practice? Most of our working models seem to posit a single unified personality, yet if Jackson is right this may be a relatively recent construct. For Howell (2008, p. 38), “The ‘self’ is plural, variegated, polyphonic and multi-voiced. We experience an illusion of unity as a result of the mind’s capacity to fill in the blanks and to forge links”. If this is indeed the emerging model for the psyche then how are we to make sense of a chaotic www.IFSCA.ca 37 environment wherein one aspect of the multiple self will cathect to an object and these relationships swirl with no discernible pattern or structure? We will likely seek to resist such a chaotic framework, and additional resistance to the view of multiple selves is described by Clayton (2005, p.9): In the health professions there is widespread agreement that dissociative identity is dysfunctional and needs to be cured. This position is based on the assumption that the healthy self is unitary and therefore multiplicity must be disordered. For Clayton, adopting a more open view of multiplicity then “depends on and informs a major shift in notions of the self, therapeutic research and practice, and social attitudes in general” (2005, p.9). All of these shifts challenge us as counsellors and as human beings. What is the nature of these challenges? I think if the personality is truly multiple then it begs the question, “What part of me is working as therapist/counsellor and with what part of my client am I working?” This is a radical shift in how we conceive of the therapeutic relationship. Yet if we do not consider this as a possibility, are we not in danger of sitting in the illusion of a unified personality (what may be considered the ‘monolithic model’ of the personality) and insisting that our clients do likewise? Might this be a disservice to them as well as us? Let us look at some of the discussion surrounding multiplicity. Rowan (1990) regards the development of subpersonalities as “autonomous or semi-autonomous parts of the person” (p. 61), noting that it “seems to be a regular temptation of people working in this field, to try to classify the IFSCA Course Manual subpersonalities in some way” (p. 85). He refers to many theorists including Freud on the superego, Jung’s complexes, Ferrucci’s subpersonalities, Watkins and Johnson’s ego-state theory, Berne’s model of Transactional Analysis, Stewart Shapiro’s concept of subselves, the Voice Dialogue work of Hal Stone and Sidra Winkelman, the “potentials” of Alvin Mahrer, Virginia Satir’s work with Parts and the work of Genie Laborde in Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP) (Pgs. 61 – 118). Similarly Schwartz (1995) observes that: Self psychology speaks of grandiose selves versus idealizing selves; Jungians identify archetypes and complexes… Gestalt therapy works with the top dog and the underdog; and cognitive-behavioural therapists describe a variety of schemata and possible selves… (suggesting) that the mind is far from unitary (p. 12). Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems (IFS) model appears to be the most effective for addressing intrapsychic dynamics when compared with the above models that incorporate multiplicity. More than simply a description of multiplicity, Schwartz articulates a structure that makes sense of the ‘chaos’ while simultaneously providing a method for bringing greater peace into the system. Pedigo (1996) notes, “it is apparent that IFS includes a fuller, more articulated concept of self” and that the “multiplicity of the mind is the most fundamental principle in the IFS model”. He states: “to understand the IFS model is to … appreciate a new paradigm in the fields of individual and family therapy” (p. 272). Here is my opportunity to now elaborate on Kuhn’s conceptualization of a paradigm shift. What does IFS offer that leads Pedigo to make such a powerful statement about a www.IFSCA.ca 38 new paradigm? Unlike many other models of multiplicity, IFS acknowledges that leadership of the system should be in the hands of what Schwartz calls the “self”. The self has the capacity to view the whole system from a metaperspective and may be regarded as the “centerpiece of the IFS model” (Schwartz, 1995, p.35). The Self (capitalized henceforth for clarity) is characterized by the presence of the following qualities: calmness, clarity, curiousity, compassion, confidence, courage, creativity and connectedness. His understanding of Self corresponds somewhat to the “willingness, openness and… gentle, kindly, friendly awareness” present in mindfulness-based treatment approaches (as discussed by Baer, 2005, p. 15) but what makes his approach truly salutogenic is his recognition that, unlike the view held by some mindfulness-based practitioners that “avoidance (of painful material) is not necessary and may be maladaptive” (p. 15), Schwartz (2005) maintains that all “parts” (including avoidant parts) are functioning in ways that they regard as necessary for maintaining the health and integrity of the system. While some may be “destructive in their present state” these behaviours may be seen as a result of a “good part forced into a bad role” (p. 16).Bringing the quality of non-judgmental curiosity to those parts reveals “the reasons that had forced them into those roles and their shame at what they had done” (p. 16). However for Schwartz (2001) Self is not merely the passive observer, it has “emergent compassion, lucidity, and wisdom to get to know and care for these inner personalities” (p. 36). He maintains that “most people have a poor self-concept because they believe that the many extreme thoughts and feelings they experience constitute who they are” (1995, p. 17) leading Lester (2007) to conclude, “The IFSCA Course Manual possibility of attributing negatively valued aspects … of oneself to one or more subselves may enable the individual to maintain high self-esteem” (p. 10). Schwartz’s model uniquely affords us a move away from the pathogenic view of the human being that has so dominated our field, in that no part of the system is unwelcome; no thoughts, feelings or behaviours are deemed as inherently bad. The IFS model offers us a method for working concretely with all the parts of the personality system holding distressing thoughts and/or beliefs and facilitating their transformation and is not to be confused with a model that solely concerns itself with Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). Indeed, DID may be seen as the result of a normal personality system adapting to severe trauma in such a way that the different parts may be unaware of each other and there is no Self available to lead. DID is characterized in its initial presentation by amnesic episodes indicating that a part has taken the lead in the system whilst other parts have been unaware of it. Typically treatment for DID involves enlisting “executive parts” to take the lead (as opposed to Self) and the prevailing view of DID is that the personality has become “fragmented” as a result of trauma; i.e. splitting of what was once a unified whole has occurred. The IFS model rejects the perspective of the unified whole and instead recognises multiplicity as the norm. Additionally, this model wholly supports the client as the locus of control, fostering dependence on the client’s Self and not the therapist’s expertise. That may sound revolutionary, and possibly threatening to our therapist ‘parts’. What may be required of us as practitioners to open to this shift? www.IFSCA.ca 39 Let me outline the model in brief in order to share more clearly the shift required in my own practice. Within the IFS framework the mind is made up of many parts. A part is a “discrete and autonomous mental system that has an idiosyncratic range of emotion, style of expression, set of abilities, desires and view of the world” (Schwartz, 1995, p.34). The personality system is understood to comprise the ‘parts’ – either “exiles” or “protectors” and Self. Exiled parts carry the burdens of extreme feelings or beliefs and are usually young parts seeking to get our attention in order to release their burdens and return to a preferred place in the system. An example of a common exiled part would be one who believes itself to be unworthy or unlovable. Because the energy of these exiles can be intense and threaten to overwhelm the system, the protector parts seek to either prevent the exiles from being activated or distract from them once they have been activated. The proactive protector parts are called “managers” as they work hard to manage the system. They are concerned with ensuring that we are seen as good people at all times and will structure our lives to ensure, as best they can, that exiled parts will not get triggered. In the example of the “unworthy” exile, a manager part may, for example, determine that applying for a challenging position is not a good idea because failing the interview may result in the feeling of unworthiness flooding the system. Better to stay within the safety of mediocrity. Unfortunately for the manager parts no matter how hard they work to prevent the exiles from becoming activated, external forces intervene. If someone loses their position as a result of downsizing, through no fault of their own, the event may nonetheless trigger the “unworthy” exile and IFSCA Course Manual the feelings and beliefs that it holds will begin to flood. It is after the activation of the exile that the reactive protectors (termed “firefighters” because their sole concern is to put out the fire, the emotional intensity of the exile) become engaged. The firefighter parts will use whatever strategy it takes to distract from the exile. That is to say if the emotional intensity of an exile is emerging into consciousness (for example feelings of intense shame) then the reactive protector may become enraged at the apparent cause of the shame (the present-day trigger), and thoughts of revenge may then dominate our conscious awareness. Drinking, drugging and the common addictions, cutting, rage, overwork, food or sex bingeing, all are common firefighter activities. Most of these don’t make us look good and so manager protectors and firefighter protectors tend to be polarized. Much of the air time taken up in what many Buddhists refer to as our “monkey minds” (because of the endless chatter) is a result of these two protector clusters fighting it out, with the managers bringing the critical ‘shoulding’ voice to the firefighter after it has ‘acted out’ in some circumstance. What gets missed when these two are so embroiled is the pain being held by the exiled part. The work then is to facilitate access to the qualities of Self in the client (particularly curiosity and compassion) in order for the exiled part to be heard by the client, and then healed as it has the opportunity to release its burdens. When the client is able to genuinely appreciate the proactive manager part’s intent to prevent distressing feelings and beliefs held by the exiled part from flooding the system, and equally appreciate the reactive firefighter’s need to engage in activities that become the system’s focus until the erupting exile’s energy has again subsided, then there is Self-energy present. Holding an appreciation for both “sides” www.IFSCA.ca 40 allows for a disidentification from each part. It is when there is sufficient Self energy present that the protector parts may allow access to the exiled part, as they can trust that the client is able to bring the requisite qualities of curiosity and/or compassion to the distressed exiled part. After being exposed to the IFS model and recognizing the multiplicity present in my own and others’ systems I experienced an ethical quandary. If I now believed that when a client was presenting with the desire to quit drinking that it was a part of them making the request (and moreover a part polarized with another part in their own system) how could I ally myself solely with the part demonizing the drinker? In the past my ‘therapist part’ would have wholeheartedly agreed that the drinking did indeed sound like a problem and would have employed various models, schema and external supports to attempt to reduce or eliminate the ‘problem’. Wasn’t that my job? Hence, my dilemma. My client had a “blended” manager part determining that his/her drinking was problematic and needed to be eliminated. I now believed that the drinking firefighter has positive intent for his/her system and was connected to a burdened part that had been exiled; and indeed, that the drinking firefighter might have preferred to be doing something less extreme but felt that it had no choice but to protect in this fashion. My new awareness informed me that the drinking activity was engaged in by a protective part of the client’s system; and that to collude with making it ‘the problem’ was to do a disservice to my client and his or her parts. Ethically I could no longer support such a stance. In order to resolve this dilemma my practice had to change: I had to become an IFS therapist, and to look at what in my IFSCA Course Manual professional work I had “believed in as the most reliable -And therefore the fittest for renunciation,” (Eliot, 1943, p. 23). I have always claimed to be client-centered and the IFS approach helps me live up to that claim in what feels like a deeper way. As I began to work with this model I became aware of my therapist part’s desires to offer advice, reassure, reframe, interpret, and call upon three decades of experience to make recommendations; all of which may subtly imply that the client is not sufficient unto him or herself. The parts of me that like to help, to fix, to offer in the interpersonal dynamic the repair of the damaged attachment bond, needed to step aside in order for me to hold and model the Self energy, the curiousity and compassion for my client’s parts that would enhance my client’s capacity to facilitate his/her own transformation. My wonderfully creative insight-facilitating parts that had formerly worked so hard to get the client to see things from a healthier and more realistic perspective (i.e. the way I saw things) were forced into early retirement. These parts relinquished their positions reluctantly; they missed their role in the therapeutic encounter. I let them know I got it; I attended to their grief. I then noticed a renewed sense of interest, even wonder as I took on my new role as ‘parts detector’ and sat more fully in my curiousity. What part of my client was being protected by the drinking part? What was activating it? How long had it been around? What could it let my client know about the burdens it was carrying? Inviting my clients to shift their focus internally brought and continues to bring its own challenges. The storytelling parts that want to be heard and do not yet know that the client’s Self can hear them may be unwilling to step back and allow the internal www.IFSCA.ca 41 enquiry of the parts they are referencing in the story. A part may worry that they are ‘Sybil-crazy’. The question, “How do you feel towards that part of you?” may seem bewildering to a protector part; yet it is an essential tool in determining if there is Selfenergy present (i.e. “I’m curious about it.” “I can see how sad it is.” “I’m glad to get to know it.”) or if a blended part is taking the lead (e.g. “I wish it would go away.” “I hate how needy it is.” “It gets me into trouble.”). Once the client’s system becomes comfortable with the method however, the work begins to flow. I have discovered that every system presents differently and I become engaged and somewhat in awe of the beauty and diversity of these inner landscapes. Some people’s parts present auditorily, others visually, releasing their information by recreating the scene they are in to the mind’s eye. One client has young parts that show her their role by wearing black Tshirts with white letters saying ‘Sad’ or ‘Abused’ or ‘Ignored’. Some systems have animated cartoon-like parts, or images that hold meaning (a three-foot tall mummy with something inside). Others are visceral, presenting sensations in different body parts. Still others have combinations of the above. Along with the remarkable diversity of these systems come similarities in the concerns of the protector parts that may feel a need to block access to the more vulnerable exiled parts. Most common is the fear of overwhelm; that a young part’s fear, sadness, anger etc. will flood the system. If you have ever seen a toddler in a full tantrum it is easy to understand the fears of the protector parts. Another common concern is that internal shifts will necessitate external changes for which the system is not ready. There may be worries about exploring parts with extreme beliefs deemed IFSCA Course Manual to be ‘core’. Beliefs about being ‘bad’, ‘deserving to suffer’ and ‘needing to be punished’ are often internalised from parents by young protectors and reiterated internally to ensure that these ‘bad parts’ don’t take hold. These protective parts can show up in a variety of ways. Often experienced as a wall, a block, a numbness, perhaps going ‘foggy’ or cloudy, suddenly thinking about having a drink or going shopping – most often these parts can be simply asked to step aside to allow continued access to more vulnerable parts and they will. If they are reluctant to step they can be asked what their concern is about the work proceeding. Their concerns can then be addressed. By staying open and listening to these parts, their roles, functions and positive intentions become clear. For the client in an abusive relationship, what would it mean for the part that keeps hoping for change if it were to let go of that hope? What would it mean for the perfectionist part if it were to stop berating? What does it fear might happen? The parts always know why they do what they do, and inviting simple curiosity, asking them about themselves, allows their tales to unfold. Much to the relief of my own figuring-it-out parts, what the client’s parts reveal is often not on my radar. I was once working with a woman who came to see me after 14 years on large doses of anti-depressant medications. Her doctor had agreed to titrate her off them and monitor her as I helped her with the depression. After a while she asked the depressed part of her that was so often blended why it needed to do that, why it needed to take her over. Its response was that if it didn’t then she would realise how boring her husband was and would have to leave him and since she was old and dependent on him financially that was too much of an upheaval. Once its role was understood its concerns could be explored. www.IFSCA.ca 42 Aside from the delight and fascination of being a parts detector for my clients and privy to their rich inner lives, and in addition to the pleasure I derive from not fostering a dependency on me as the therapist, the most rewarding aspect of this work is witnessing the changes that take place within my clients’ systems that are permanent and healing. Previously I was often left with a nagging doubt about my effectiveness. I would spend time with clients, they would ‘graduate’ from their therapeutic work, they would report positive changes in their lives, yet I was left wondering if the work ‘took’, if without the bolster of weekly support they would be able to maintain the ground that they had apparently gained. Working with the IFS method it is absolutely clear to me that the exiled parts are healed, and this occurs through the process of “unburdening”, described below. Let’s say that a client presents with binge eating as the issue that needs to be addressed. She may be able to identify that tension between her and her partner leads her to scan the interior of her fridge on a regular basis, seeking solace. We can ask her to bring her attention to the eating part (a “firefighter” in this model) and to appreciate it for its attempts to soothe the distress in the system. This may take a while as the polarized “manager” parts may be reluctant to step aside to allow the appreciation to flow: manager parts view firefighters as problematic. Once the genuine appreciation for the firefighter is felt then it will likely be willing to share information about itself, its protective role, how it feels about that role (including anything it might like to change if it were possible) and information about the exiled part to which it is connected. The therapist’s interventions here are simply to determine how much of the client’s Self is present by repeatedly checking how the client feels towards the presenting part to IFSCA Course Manual determine if there is an open-hearted connection. This ‘script’ is radically different from the interventions with which most of us are familiar. When a firefighter part trusts the client’s Self enough it may allow access to the exile, who will then, in the presence of the client’s curiosity and compassion, be able to let the client know about the burdens it holds. It may begin by saying that it feels bad when its partner is mean to it. Further enquiry may yield information that it feels unloved. Asking how long it has felt that way will lead to its initial presentation in the system and it may reveal that it is six years old and has nonetheless ‘grown up with’ the client; becoming activated at various times in the client’s life. Asked about its inception in the system, the world where it is ‘stuck’, it may tell the story of how its Dad ignores it when it asks for attention. It may tell of a mother in clinical depression who is unavailable to it. In trying to comprehend why it feels so isolated, why it is not being nurtured, it will logically conclude (with all the self-focus of a six-year-old coupled with the belief in the God-like perfection of the parents) that it is not loved because it is unlovable; it is flawed. Were this belief to obtain within the system the child could not thrive; so the part holding this distressing belief is exiled to a corner of the psyche from which it later seeks to return. Now in the client’s adult life this part gets triggered by an unavailable partner and a firefighter immediately jumps in and uses food to distract from the potentially threatening feelings of the exiled part. Once the client has heard all that the exile has to say, and it knows that the true depth of its misery has been heard with compassion, it is now ready to release the burdens it took on and return to either its original role, or a new preferred role in the system. We can instruct the client to invite the part to release its www.IFSCA.ca 43 burdens to light or any of the elements in such a way that they will never return. It can now be invited to fill itself with whatever qualities will help it to move forward – perhaps it will choose confidence and the knowledge of its own worth. Returning to the rest of the system we can ask if other parts have comments or concerns about the shift that has occurred. Often a protector may wonder what its role is now and may be relieved to discover that it can still choose yummy things to eat, but its behaviour will no longer be driven by the need to distract from the emotional fire of the exile. In the external world the client may notice that her partner’s mean behaviour no longer triggers a feeling/belief of being unlovable, and her available response repertoire is greatly increased. Interestingly these changes are reported as feeling minimal and as if the client had always responded this way. Therapy derives from the Greek “therapeia”, to attend. The elegance of this model, the simple requirement that the therapist compassionately attend the client’s Selfhealing via the exploration and unburdening of parts holding extreme feelings and/or beliefs, invites us as practitioners back to our roots. In the words of T.S. Eliot (Eliot, 1943, p. 39): With the drawing of this Love and the voice of this Calling We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Is the Internal Family System model the emerging paradigm in psychotherapy? I am encouraged by recent shifts in our understanding of the relationship between the mind and the brain and the role of mindfulness as outlined by Siegel (2007) and the evident neuroplasticity of the brain (Doidge, 2007). Both authors present work that supports the IFS framework. Time will tell if this is the direction in which the field is shifting. All I know for myself is that my re-engagement with the beauty of the work, my realistic hope for positive client outcomes, and my capacity to hold them in their highest place even when their parts may be presenting a different picture affords me much thankfulness that my own parts have guided me to be doing this sacred work. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 44 References Baer, R. (2005).Mindfulness-based treatment approaches: Clinician’s guide to evidence base and applications. San Diego,CA: Academic Press. Chandella, N. (2008). I have that within which passeth show. International Journal of the Humanities, 6(2), 61-70. Clayton, K. (2005). Critiquing the requirement of oneness over multiplicity: An examination of dissociative identity (disorder) in five clinical texts. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 1(2), 9-19. Cognitive revolution (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 15, 2011, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_r evolution Doidge, N. (2007). The brain that changesitself: Stories of personal triumph from the frontiers of brain science. New York, N.Y: Viking. Eliot, T. (1943).The four quartets. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. Howell, E. (2008).The dissociative mind. New York: Routledge. Jackson, R. (1981).Fantasy: the literature of subversion. London: IFSCA Course Manual Routledge. Kauffman, J. (2002). The psychology of disenfranchised grief: Liberation, shame, and self-disenfranchisement. In Doka, K. (Ed), Disenfranchised grief: new directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Champaign, Il: Research Press. Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press. Lester, D. (2007). A subself theory of the personality. CurrentPsychology, 26, 1 – 15. Pedigo, T.B. (1996). Richard C. Schwartz: Internal family systems therapy. Family Journal 4(3), 268277. Rowan, J. (1990).Subpersonalities: the people inside us. London: Routledge. Schwartz, R. (1995). Internal family systems therapy. New York: Guilford Press. Schwartz, R. (2001).Introduction to the internal family systems model. Oak Park, Il: Trailhead Publications. Siegel, D. (2007). The mindful brain. New York, N.Y:W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. www.IFSCA.ca 45 Self-leadership and the Fire Drill Exercise Richard C. Schwartz Ph.D Reprinted from the Self to Self newsletter Vol. 2 No. 1 Spring 1997 ...extreme parts feed off the extreme reactions they create in the other’s parts Over the years, the Self and the concept of Self-leadership has become increasingly central to the IFS model. Effective therapists have learned to maintain Self-leadership in the face of provocation from their clients’ parts. More generally, however, the more one’s life is Self-led, the more one is able to relax and enjoy it and the more harmony one has in internal and external relationships. It is very similar to what Paul Ginter described as mindfulness in the last newsletter, and, like mindfulness, Self-leadership requires practice. As therapists we are fortunate to have a set of daily Self-leadership practice periods, otherwise known as sessions. My sessions are times when I deliberately concentrate on practicing Selfleadership and my clients’ parts provide a variety of challenges and provocations. Before a client arrives I will try to feel the energy of the Self and will try to keep that energy flowing through the whole session. I’m also frequently asking my parts to step back and trust my Self, trust that energy. With some clients’ parts this is very difficult and my parts still take over at times. But it becomes easier with practice and, when I’m successful, it makes doing therapy a pleasure. In collaboration with Ron Kurtz, the developer of Hakomi, I’ve devised an exercise to help people practice Self-leadership in the face of provocation. It’s called the Fire Drill because it resembles times when one has to rehearse for an emergency. That is, there are times in life when our parts are suddenly activated by a person or situation and we don’t have time to go inside and find out what’s bothering them or to do any extensive inner work. The Fire Drill can be done with two or more people, one of whom is the “provokee.” The provokee is to think of a situation or person in his or her life that activates parts. The provokee then describes that situation or person to the others so that one or both can be the provoker - can role-play that person or situation. The provoker then tries to activate the provokee’s parts in the way described, and the provokee allows his or her parts to get upset and take over. Once the provokee is stirred up, the provoker (or an observer if there are others witnessing) pauses the action and invites the provokee to go inside and ask his or her parts to step back and trust the Self to handle the provoker. When there’s some degree of agreement, the provokee returns and tries to maintain Self-leadership as the provoker resumes the activating behavior. When that feels complete, the provokee, provoker and observers discuss the exercise. To maintain Self-leadership in the face of provocation, our parts must be able to trust our Selves enough to quickly step back and let our Selves handle the situation, despite the fact that they’re still upset. When this works, a person will feel upset inside, but will not be overwhelmed by the upset parts and will remain the “I” in the storm -- dealing calmly, confidently and even compassionately with the situation, while sensing parts that are seething or cowering inside. The Self may want to speak for some of those parts so they feel acknowledged, but not have the parts take the driver’s seat. When your parts take over and express their feelings, it often has the effect of activating parts in the other and of distorting your perceptions as the speaker. In contrast, the IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 46 Self can say the same words that a part would say and yet the listener is okay hearing it because they hear the caring behind it. Their connection to you isn’t broken, whereas it often is broken when parts take over. Self-leadership is disarming, it melts the other’s protectors, and nurtures the other’s exiles -- it strengthens the Self-to-Self connection that is what we’re here for. After the storm has cleared and you have some time, you can go to your parts and help them with their reactions. These situations are always fertile. When parts are activated, their burdens are more evident and you can help them unburden. When they trust the Self to lead in a tense situation and then the Self cares for them afterward, they feel safe and can further relax into the comfort of Self-leadership. Some people think that Selfleadership means always being warm, open and nurturing, so they’re reluctant to trust their Self in situations that call for assertiveness. This is a misconception. The Self can be forcefully protective or assertive. The energy of the Self is both nurturing and strong -- yin and yang. Thus, it’s possible and preferable to let the Self handle occasions where you have to set limits or defend yourself as well as times when you are in a healing role. Much of the martial arts is about the practice of Self-leadership. This is not to say that parts should never take over, just that Self-leadership means that when they do, it’s by choice rather than by automatic reaction. There are times when it’s fun or necessary to allow a part to take over -- e.g., at a party, or when a person won’t hear you any other way. But that should be temporary and by conscious choice. Thus, the Fire Drill is an excellent way to: (1) find and heal parts that are activated by certain situations (2) increase trust in the Self, and (3) rehearse for real situations. There is another big lesson that people often receive through the exercise. Frequently the provoker finds that he or she cannot continue to provoke, or has much more trouble doing so, once the provokee returns and is leading with the Self. They report that it’s as if the game is over, that it’s no longer fun to bother the provokee because the payoff is gone. This is because extreme parts feed off the extreme reactions they create in the other’s parts, and because the Self of one person elicits the Self of the other. This is why Self leadership is so much more effective in getting what you want from others -- love, consideration, attention, connection, compromise -- because it’s so much easier to deal with the other’s Self than his or her parts. Self-leadership is disarming, it melts the other’s protectors, and nurtures the other’s exiles -- it strengthens the Self-to-Self connection that is what we’re here for. As hard as it is to maintain at first, Selfleadership ultimately saves energy because you don’t go away from interactions still stewing about them. Parts will have all kinds of arguments about why it’s crucial for them to remain in control, but they really wish they didn’t have all that responsibility and want the Self to prove it can handle life for them. Thus, like mindfulness, Selfleadership is a kind of spiritual practice in which we can engage continuously. As I mentioned earlier, for the therapist, this turns therapy into a spiritual practice rather than merely a job or a career. But the concept of Self-leadership is relevant for any endeavor, and I look forward to opportunities to apply it to other contexts -- from schools to corporations. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 47 The Fire Drill exercise is a good way to practice Self-leadership in any context; for example, I’ve used it with couples quite effectively: One partner (A) thinks of something the other (B) does that bothers him or her and asks B to do that thing until parts of A are stirred up. A then goes inside and helps his or her parts step back and let A’s Self deal with the parts of B. As you know, if you are a part of a couple, this is a very difficult task. It’s in the heat of the battle when couples have the most trouble maintaining Self-leadership because, as the law of polarization predicts, each is afraid that if they don’t protect themselves with their parts, the other will run amok or get away with something. Yet, if one can remain the “I” in the storm, then often the other’s parts retreat also. The pretend nature of the fire drill exercise with couples can make it playful also. Each is asked to deliberately do something that bothers the other. This produces an “as if” set in which they can safely experiment with old and some new patterns. The danger in the fire drill exercise is that the provokee’s parts may get so stirred up that they overwhelm the person and trigger inner escalations. Young parts cannot always distinguish between role-play and reality. They may come to believe that the provoker really means it. For this reason, I rarely become the provoker with clients, and when I do, I am careful about the kind of provoking I’m willing to do. Afterwards, I’m careful to “derole” by having clients tell their young parts that it was pretend and that I’m not that person. This is an important step in any use of the Fire Drill exercise. Also, there is the potential for the provoker to get carried away by the parts he or she is using in the role-play such that it becomes hard to return to Self-leadership. To avoid this, it behooves therapists to have the provoker check before hand with the parts that will be enlisted to see if that potential exists. As we continue to explore what Self-leadership entails, there is increasing need to find ways to practice it. I encourage readers to share the ways they have found to achieve and maintain it. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 48 Module 4 “I’m Here” Leading as YourSelf IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 49 Self-leadership Perhaps best described as being the calm at the center of the storm that life's passages can bring us, Self-leadership enables us to bring curiousity internally to the unknown and compassion to suffering. In terms of how we lead our lives it allows us to love our quirky parts and bring comfort and companionship to the lonely parts of us; paradoxically they are less alone when we – Self – can be with them. I often say that someone has to love my parts and it might as well be me; in reality who else in this world is likely to unconditionally love every part of me without getting triggered into their own “stuff”? And my parts don't have to love or even like each other. That’s my job. Self-leadership helps the gestalt that is the personality system to operate as an alliance. As we spend more time appreciating our parts, helping them out and holding them in our awareness we find ourselves increasingly living our day-to-day lives with lots of Self energy. Typically, at some point we will get “hijacked” or notice "I'm" not doing okay. That just means a part is getting our attention - so we attend to it. Sometimes the blending of the distressed part (sad… bitter… lonely… depressed) may last for a long while until we become aware that the “me” feeling the distress is a part. Once we return to that clarity we are able to disidentify from it and see what it needs from us; returning us to a more Self-led state. Over time this process is more readily available to us. As I see it the goal here is not the elusive Buddha-like enlightenment; nor the permanent Christ-like compassion and love for all (“or maybe I just haven’t gotten there yet” – says a part) but more peace, more clarity, more of the “C” qualities available within the system more of the time. So, when my grocery-shopping part goes to the market on Saturday he has more ease within himself and more connection available between him and the stallholders. And I can share with him my appreciation for his work. I have an eating part that loves fresh salad greens – without my shopping part my eating part’s life would be impoverished. Self-leadership and Decision-making Dick Schwartz has observed (in his essay “The Self”) that “Once a person’s parts learned to trust that they didn’t have to protect so much and could allow the Self to lead, some degree of Self would be present for all their decisions and interactions. Even during a crisis, when a person’s emotions were running high, there would be a difference. Instead of being overwhelmed by and blending with their emotions, Self-led people are able to hold their center, knowing that it was just a part of them that was upset now and would calm down eventually.” IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 50 If we understand Self as having a desire for harmony and healing, we can understand its role in decision-making as being similar to that of a mediator. Let’s say there was a major decision to make: moving to another town mainly for work and having to uproot the family as a result. Self can: • • • • Listen to all the stakeholders (parts) with respect Ask that parts be respectful of each other as they present their information and concerns: they will all be heard; they do not have to agree If parts seem to have a lot of exile or protector energy (I have to stay here, I just have to...") they may require some work to come to a less intense place The Self-led decision is one that involves moving forward with the least amount of backlash and therefore less stress Parts are not unreasonable - if they have been listened to and invited to be aware that Self is making a decision based on the input of all the stakeholders in the system they can tolerate not getting 100% of what they wanted. It is helpful to thank the parts for their willingness to compromise. It can fun to get to know the different parts as it becomes increasingly possible to move from reactivity to response-ability The Self-Led Therapist: Continued Engagement and Burnout Prevention Most of us have been taught that one of our most valuable gifts is to listen empathically, to put ourselves in the other’s shoes, to walk a mile etc. One of the tenets of reflective listening is to listen for the meaning – often the emotional impact – of what is being said in order to reflect it back to the person, so they know they are being heard and can, in effect, hear themselves. Tania Singer, from a paper in Current Biology Vol 24 No 18, 2014 entitled “Empathy and Compassion” states: “Empathy makes it possible to resonate with others’ positive and negative feelings alike — we can thus feel happy when we vicariously share the joy of others and we can share the experience of suffering when we empathize with someone in pain.” Empathic parts help us to make friends, manage our parents, engage in social interaction, cry at movies and connect with others in meaningful ways. Yet when we repeatedly draw on our empathic parts in the therapeutic encounter the results can be detrimental. Singer again: “While empathy refers to our general capacity to resonate with others’ emotional states irrespective of their valence — positive or negative — empathic distress refers to a strong aversive and self-oriented response to the suffering of others, accompanied by the desire to withdraw from a situation in order to protect oneself from excessive negative feelings.” IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 51 IFS understands that the empathic response comes from a part; it is not an aspect of Self. Singer’s research supports this contention, demonstrating that the empathic response lights up neural circuitry different from what is present during a compassionate response. “Compassion… is conceived as a feeling of concern for another person’s suffering which is accompanied by the motivation to help. By consequence, it is associated with approach and prosocial motivation. In order to prevent an excessive sharing of suffering that may turn into distress, one may respond to the suffering of others with compassion. In contrast to empathy, compassion does not mean sharing the suffering of the other: rather, it is characterized by feelings of warmth, concern and care for the other, as well as a strong motivation to improve the other’s wellbeing. Compassion is feeling for and not feeling with the other.” In conversation with Dick Schwartz I suggested that compassion might be an aspect of what Professor Amit Goswami, a researcher in quantum physics, calls ‘non-local consciousness’. Local consciousness may be considered as our individual personality systems (parts). Non-local consciousness, according to Goswami, considers “consciousness as the unified field, something that connects us all. It is what Jungians might call the collective consciousness, what Vedantists might call Self”. Dick agreed that this was likely the case. Compassion, then, is boundless because it is not bounded within the personality system. Compassion cannot be overwhelmed nor become ‘fatigued”. Compassion is a limitless resource. And the way compassion heals is by manifesting the willingness to stay connected. When a counsellor/therapist/human being manifests compassion in this way in the light of another’s suffering they invite the other to mobilise their own compassion and bring it to their own suffering parts so that they get heard and may be healed (unburdened). An IFS therapist is repeatedly and consciously working from a place of compassion. Singer’s work demonstrates that “compassion training” results in changes in neural activity. “Given the potentially detrimental effects of empathic distress, the finding of existing plasticity of adaptive social emotions is encouraging, especially as compassion training not only promotes prosocial behavior, but also augments positive affect and resilience, which in turn fosters better coping with stressful situations” IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 52 Lorne Ladner, author of “The Lost Art of Compassion: Discovering the Practice of Happiness in the Meeting of Buddhism and Psychology” offers this understanding of compassion from her essay ‘Positive Psychology and the Buddhist Path of Compassion’, “the expression of simple human compassion is healing in and of itself. By developing deep, powerful feelings of compassionate connection with others… we can learn to live meaningful and joyful lives. Only such feelings can help us to learn experientially how to… give of ourselves without becoming exhausted or burnt out - such feelings of joyful compassion teach us how taking care of others is actually a supreme method for taking care of ourselves.” Self-led compassion in the therapy session says: “I see, feel and hear you. I will not abandon this connection with you. I will not seek to change, nor deny your truth. In your experience of the unbearable you will be connected to me and through me.” When a client’s Self is available to their own parts, this is the connection that facilitates healing. I have adapted the following article by veterinarian Trisha Dowling who beautifully articulates the compassion/empathy distinction. Compassion does not fatigue! Trisha Dowling\ In the health care professions, the words compassion and empathy are frequently used interchangeably, and the term compassion fatigue is often used to describe a type of posttraumatic stress disorder. According to Dr. Charles Figley of Tulane University, “Compassion fatigue is a state experienced by those helping people or animals in distress; it is an extreme state of tension and preoccupation with the suffering of those being helped to the degree that it can create a secondary traumatic stress for the helper.” But emerging research from the social neuroscience laboratory of Dr. Tania Singer of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Germany shows that compassion fatigue is a misnomer and that it is empathy that fatigues in care givers, not compassion! To explain the differences, Singer developed a hierarchy model of empathy and compassion (Figure 1). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 53 for Part’s with Figure 1 Hierarchy model of empathy and compassion. Empathy Empathy allows us to resonate with others’ positive and negative feelings. We can feel happy at the joy of others and we can feel distress when we observe someone in physical or mental pain. While sharing positive emotions with others is certainly pleasant, the sharing of negative emotions can be difficult. The development of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) opened the way for neuroscientists to explore the brain circuitry involved when people experience pain in themselves as well as when they observe someone else feeling pain. To investigate painrelated empathy, Dr. Singer studied married couples, with the assumption that couples are likely to feel empathy for each other. Using fMRI scanners, she investigated the brain networks that were activated when a painful stimulus was applied to the hand of one partner and the other partner could see and hear their reaction. Areas of the anterior insula and the anterior middle cingulate cortex were activated when subjects received pain but also when they observed that their partner experienced pain. Other parts of the pain network were activated only in the partner actually receiving the painful stimulus. Singer concluded that the part of the pain network associated with its emotional qualities, but not its sensory qualities, mediates empathy for suffering. Thus, both the firsthand experience of pain and the knowledge that a beloved partner is experiencing pain activate the same emotional brain circuits. In human interactions, feeling empathy is the first step in building social connection. But it is very important that in empathy you feel with the other person, but you don’t confuse yourself with the other; you still know that the emotion you resonate with is the emotion of the other person. A good example of appropriate empathy is helping a client through the euthanasia experience. As I have euthanized many of my own animals during my 30year veterinary career, I feel my own sadness during the euthanasia process. But I can tell that I’m feeling and honoring their grief and not making the grief my own. After empathy establishes the connection between us, the second step of the hierarchy can diverge into the processes of empathetic distress or compassion and empathetic concern. Whether observation of distress in others leads to empathic concern and IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 54 altruistic motivation or to personal distress is dependent on noticing which of our parts may be getting triggered and inviting it to soften back (ideally to be attended to at a later date). I.e. am I resonating with them from self or is a part of me getting triggered When we take on the emotional pain of the other person as our own pain, empathetic distress results. If I’m not able to distinguish my client’s grief from my grief over the loss of my own animals, then I move into empathic distress. Empathic distress is the strong aversive response to the suffering of others, as an exile gets triggered. Our manager parts then bring the desire to withdraw from a situation in order to protect ourselves from excessive negative feelings. As I may become overwhelmed by my own euthanasiaassociated grief, a part of me tries to avoid the aversive situation (the trigger) by, for example, rushing the client through the euthanasia process and withdraw from further interactions with my client. Other strategies in our work may include changing the subject, talking about the trauma and others. The fMRI data show that an exile being triggered leads to increased activation in brain areas involved in the processing of threat or pain, such as the amygdala. Chronic pain, whether mental or physical, depletes dopamine levels within brain circuits mediating reward and motivation. When locked into empathic distress, or blended with an exile, we have a blunted capacity to experience pleasure along with decreased motivation for natural rewards. Chronic depletion of dopamine from repeated episodes of empathic distress is what leads to burnout, characterized in health care professionals as emotional exhaustion, withdrawal, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of personal accomplishment due to work-related stress. Compassion In contrast to empathy, compassion is characterized by feelings of warmth, concern, and care for the other, as well as a strong motivation to improve the other’s wellbeing. Compassion goes beyond feeling with the other to feeling for the other. Unlike empathy, compassion increases activity in the areas of the brain involved in dopaminergic reward and oxytocin-related affiliative processes, and enhances positive emotions in response to adverse situations. While empathizing with my client making a euthanasia decision invokes my own feelings of sadness, moving to compassion for my client’s situation results in positive emotional feelings that cause me to take action to help my client. Instead of withdrawing and rushing through the procedure as my protective part would urge, compassion enables me to slow down and be present with my client without experiencing distress. This is the critical property of compassion that differentiates it from empathy. Because compassion generates positive emotions, it counteracts negative effects of empathy elicited by experiencing others’ suffering. Unlike the dopamine depletion that occurs from activation of the pain networks, the neural networks activated when people feel compassion towards others activate brain areas linked to reward processing that are full of receptors for oxytocin and vasopressin, the neuropeptides that are crucial in attachment and bonding. Compassion does not fatigue — it is neurologically rejuvenating! IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 55 Therapy as Service Manager-led Therapy Whether from a humanistic or spiritual perspective we may regard therapy as being of service to others. Service can be motivated by mangers, or have more Self energy informing it. When managerial it may be connected to an exile: “If I prove I am a good/Spiritual person by helping all these people then it means I have worth”. If a manager such as this takes the lead (in order to keep a “worthless” exile at bay), then there will likely be consequences. If the work is manager-led then the therapist may overcommit, leading to resentment. The resentful part may be present in session, actively disliking clients, and requiring more work to get it to soften back. Similarly, money-managers (connected to scarcity parts) may overload the schedule. Some parts that feel they need to help the world not suffer as they did (who may be connected to some notion of vicarious healing: “If I help all these people it means I’m okay”) or a martyred rescuer part: “Helping these folks gives meaning to my own suffering”. All of these managers point to exiles needing attention. If they continue to lead the system they will generate internal disharmony, possibly resentment and burnout. Self-led Therapy This is more likely to occur when the therapist moves from a place of, and seeks, harmony. The way Self heals internally is that when it encounters a part that is in distress (i.e. not its natural state) Self naturally want to know “how come…” what happened that this part is holding some burden? (This is the Self-led curiousity that facilitates the work). When the part has shared its story, which invariably means talking about hard stuff, Self acknowledges how hard it has been to hold all of that (compassion) and we can facilitate a process whereby the part no longer needs to hold the distress and can take in what it needs to return to its natural state (wherein it has its own Self energy). Commonly something like “unworthy” get heard and released and “confidence” may be taken in. The part then experiences itself as whole again, the protectors connected to it can relax and may seek to modify their roles, and there is more of a sense of harmony in the system. Getting to know your therapist parts’ agendas and/or beliefs they hold about the work (some of which they may have taken on from former training) will lead you to healing any of your own exiles connected to the work, and allow you to present more as a Self-led parts detector. When the system has a lot of Self-leadership available Self is also available for the external world. Injustice (which creates disharmony) catches the attention of Self and our internal resources may be mobilised to take action. The injustice may be in the form of the 47 year old client whose life choices have been made in the light of a 6 year old IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 56 deeply shamed part that s/he carries inside; or something like systemic racism or other injustices inherent within our sociopolitical landscape. Self, as a form of Compassion-in-Action, can act to balance internal and external demands. If you like, Self may be thought of as the Axis of compassion – attending internally and external to facilitate balance. When our internal system requires attending to, Self is available to bring it back into harmony. When the external systems require attention (a client in distress/combatting injustice) Self is available. One of the common impediments to attending to our parts are managers that have been told we are “selfish”. Selfishness is usually a shaming term levied at us in our childhoods when our wants/needs/desires run counter to the wants/needs/desires of an authority figure. Shaming energy is intense and, when being directed at us by a trusted adult, often internalized as a burden. Managers seek to avoid the recurrence of this so will determine that we are “selfish” if we are not putting others first. This often calls into play peoplepleasers engaging with others, and minimisers telling us our needs are not that important. This unbalanced state often leads to backlash from resentful firefighters, which managers then seek to repair… and the dynamics of tension continue. Letting the shaming manager know that you appreciate its intent, and that you are available (in fact it may be considered as your job in a Self-led system) to hear the parts and attend to their needs, may help it to relax. All of your parts have value – even if they do not value each other. Listening in and letting them know that you value them goes a long way to experiencing the inner peace (the C of Calm) that is available. The more harmony that exists within your own system as you take care of your parts, the more Self energy becomes available for clients as you help their Self energy to be available to balance their own system. To sum up: • • • • • • • • Self seeks Connection The Connection it seeks is with Self (contented parts hold a lot of Self energy) Discontented part have taken on burdens as a result of external circumstances Self seeks to learn about the distress and, in its compassionate witnessing, facilitate the release of the burden The part then returns to its natural state Self may be considered a bi-directional axis of compassion: facilitating harmony and healing in the internal and external worlds and oscillating between the two Service both flows from and seeks to facilitate harmony and balance Both the internal and the external worlds may be the focus for Self’s compassionin-action IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 57 The 5 Ps of the IFS therapist • Presence • Patience • Persistence • Playfulness • Perspective The Laws of Inner Physics - Dick Schwartz: Law 1: You will relate to your children when they resemble one of your parts, in the way you relate to your own parts If you hate your own vulnerability, when they are vulnerable, you will shame them. Or the same thing will happen with your rage. The same thing happens with our peers. If they disdain their vulnerability, they will disdain yours. Law 2: Willpower will backfire. It doesn’t work in the inner world Willpower is a manager’s strategy and attempt to override the wants, needs and desires of other parts. Law 3: Unblending happens All we need is the intention of the part to unblend, and it can happen. Law 4: Nothing in the internal world has any power over you if you are not afraid of it If there is fear of, for example childhood sexual abuse, or fear of a part who wants to die; this fear is coming from a part. We need to take care of that part, address its concern, and invite it to a place of safety internally; reassuring it that Self is available and nothing can overwhelm compassion. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 58 Embrace Your Self-Destructive Impulses? How People Can Connect with Dark Parts of Their Psyche for Personal Change - Dick Schwartz As therapists increasingly incorporate mindfulness into their work, they’re discovering what Buddhists have known for centuries: everyone (even those with severe inner turmoil) can access a state of spacious well-being by beginning to notice their more turbulent thoughts and feelings, rather than becoming swallowed up by them. As people relate to their disturbing inner experiences from this calm, mindful place, not only are they less overwhelmed, but they can become more accepting of the aspects of themselves with which they’ve been struggling. Still the question remains of how best to incorporate mindfulness into psychotherapy. A perennial quandary in psychotherapy, as well as spirituality, is whether the goal is to help people come to accept the inevitable pain of the human condition with more equanimity or to actually transform and heal the pain, shame, or terror, so that it’s no longer a problem. Are we seeking acceptance or transformation, passive observation or engaged action, a stronger connection to the here-and-now or an understanding of the past? Many therapeutic attempts to integrate mindfulness have adopted what I’ll call the passiveobserver form of mindfulness—a client is helped to notice thoughts and emotions from a place of separation and extend acceptance toward them. The emphasis isn’t on trying to change or replace irrational cognitions, but on noticing them and then acting in ways that the observing self considers more adaptive or functional. As an illustration, let’s consider how more traditional therapeutic approaches contrast with more mindfulness-based methods in helping a client dealing with the mundane challenge of feeling nervous about going to a party. A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) intervention might begin by identifying the self-statements that are generating anxiety—a part of the person that says, in effect, “Don’t go because no one likes you and you’ll be rejected.” The client might then be instructed to dispute these thoughts by saying, “It’s not true that no one likes me” and naming some people who do. A clinician trained in a mindfulnessbased approach like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) might have the client notice the extreme thoughts about rejection without trying to change them, and then go to the party anyway, despite the continued presence of the irrational beliefs. As this example shows, mindfulness allows you to no longer be fused or blended with the irrational beliefs, releasing your observing self, who has the perspective and courage to act in positive ways. This shift from struggling to correct or override cognitive distortions to noticing and accepting them is revolutionary in a field that’s been so dominated by CBT. There’s a large body of research on ACT, from Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction, and from the ground-breaking work of Marcia Linehan’s Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) with borderline personality disorder, suggesting that the shift is a powerful one. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 59 Clearly, learning to mindfully witness experiences helps clients a great deal, even those with diagnoses previously considered intractable. A vivid cinematic example of this witnessing process can be found in the Academy Award– winning film A Beautiful Mind, in which we’re given a sense of what it’s like to be awash in an irrational thought system. In the beginning of the movie, the disturbed math genius John Nash (played by Russell Crowe) is so identified with the paranoid part of him (a black-suited FBI agent played by Ed Harris) that we, the viewers, are drawn into his scary world with him. Gradually Nash is able to separate from his paranoia—to observe his inner FBI agent with some distance and objectivity, rather than believing his conspiratorial rantings. With this mindful separation comes greater peace of mind and ability to function in his life. But while diminished in their intensity and their power to control his behavior, at the end of the film we see that Nash’s voices continue to reside in him. He’s simply learned to live with his extreme beliefs and emotions without being enslaved by them. But what if it were possible to transform this inner drama, rather than just keep it at arm’s length by taking mindfulness one step further? The Second Step As a therapist, I’ve worked with clients who’ve come to me after having seen therapists who’d helped them to be more mindful of their impulses to cut themselves, binge on food or drugs, or commit suicide. While those impulses remained in their lives, these clients were no longer losing their battles with them, nor were they ashamed or afraid of them any longer. The clients’ functioning had improved remarkably. The goal of the therapeutic approach that I use, Internal Family Systems (IFS), was to build on this important first step of separating from and accepting these impulses, and then take a second step of helping clients transform them. For example, Molly had been in and out of hospital treatment centers until, through her DBT treatment, she was able to separate from and be accepting of the part of her that had repeatedly directed her to try to kill herself. As a result of that successful treatment, she’d stayed out of the hospital for more than two years, was holding down a job, and was connected to people in her support group. From my clinical viewpoint, she was now ready for the next step in her therapeutic growth. My goal was to help her get to know her suicidality—not just as an impulse to be accepted, but as a “part” of her that was trying to help her in some way. In an early session, after determining she was ready to take this step, I asked her to focus on that suicidal impulse and how she felt toward it. She said she no longer feared it and had come to feel sorry for it, because she sensed that it was scared. Like many clients, she also began to spontaneously see an inner image, in her case a tattered, homeless woman who rejected her compassion. I invited her to ask this woman what she was afraid would happen if Molly continued to live. The woman replied that Molly would continue to suffer excruciating emotional pain. With some help in that session, Molly was able to embrace the woman, show her appreciation for trying to protect her from extreme suffering, and learn about the hurting part of her that the woman protected her from. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 60 In subsequent sessions, Molly, in her mind’s eye, entered the original abuse scene, took the little girl she saw there out of it to a safe place, and released the terror and shame she’d carried throughout her life. Once the old woman could see that the girl was safe, she began to support Molly’s steps into a fuller life and stopped encouraging her to try to escape the prospect of lifelong suffering through suicide. In this way, the “enemy” became an ally. The Paradox of Acceptance Years ago, Carl Rogers observed, “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.” In other words, carefully observing and accepting our emotions and beliefs, rather than fighting or fearing them, is a precursor for using that same mindful state to help them transform. Once people come to compassionately engage with troubling elements of their psyches, they’re often able to release difficult emotions and outmoded beliefs they’ve carried for years. For me, this process of compassionately engaging with the elements of our psyches is a natural second step of mindfulness. If you feel compassion for something, why just observe it? Why not engage with it and try to help it? Actually, some prominent Buddhist leaders advocate taking this next step. Thich Nhat Hahn, Pema Chodron, Tara Brach, and Jack Kornfield all encourage their students not just to witness their emotions, but to actively embrace them. Consider this quote from Thich Nhat Hahn about handling emotions: “You calm your feeling just by being with it, like a mother tenderly holding her crying baby. Feeling the mother’s tenderness, the baby will calm down and stop crying.” So it’s possible to first separate from an upset emotion, but then return to it and form a loving inner relationship it, as one might with a child. The Buddhist teacher Tsultrim Allione revived an ancient Tibetan tradition called Chod, which has practitioners feeding rather than fighting with their inner “demons.” She finds that once fed with curiosity and compassion, these inner enemies reveal what they really need, feel accepted and heard, and become allies. It’s possible to go beyond simply witnessing our inner world to actually entering it in this mindful state and interacting with the parts of our psyches with the same kind of loving attunement that creates secure attachments between parents and children, or between therapists and clients. More than a Monkey Mind This is harder to do if therapists consider clients’ inner worlds to be populated by an annoying ego or agitated monkey mind. In some Buddhist traditions, the myriad thoughts and feelings, pleasures and pains we have are considered to be the product of an ego, which is conditioned by the materialistic culture to become attached to transitory things and keep you from your higher spiritual path. If that’s your starting assumption, you may notice feelings of happiness and sorrow with acceptance, but you aren’t likely to want to spend much time getting to know them. You’ll fear that the more time you entertain such thoughts and feelings, the more attached you’ll become to the material world. If, on the other hand, you consider your thoughts, emotions, urges, and impulses to be coming from an inner landscape that’s best understood as a kind of internal family, IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 61 populated by subpersonalities, many of whom are childlike and are suffering, then it makes more sense to take that next step of comforting and holding these inner selves—as Thich Nhat Hahn advises—rather than just observing and objectifying them. All clients need to do to begin exploring this apparently chaotic and mysterious inner world is to focus inside with genuine curiosity and start asking questions, as Molly did, and these inner family members will begin to emerge. As the process continues, clients will be able to form I-thou relationships with their parts, rather than the more detached, I-it relationships that most psychotherapies and many spiritualities foster. Once a client, in a mindful state, enters such an inner dialogue, she’ll typically learn from her parts that they’re suffering and/or are trying to protect her. As she does this, she’s shifting from the passive-observer state to an increasingly engaged and relational form of mindfulness that naturally exists within: what I call her “Self.” Having helped clients access this engaged, mindful Self for more than 30 years now, I’ve consistently observed that it’s a state that isn’t just accepting of their parts, but also has an innate wisdom about how to relate to them in an attuned, loving way. I’ve observed over and over clients’ enormous inborn capacity for self-healing, a capacity that most of us aren’t even aware of. We normally think of the attachment process as happening between caretakers and young children, but the more you explore how the inner world functions, the more you find that it parallels external relationships, and that we have an inner capacity to extend mindful caretaking to aspects of ourselves that are frozen in time and excluded from our normal consciousness. This Self state has the ability to open a pathway to the parts of us that we locked away because they were hurt when we were younger and we didn’t want to feel that pain again. As clients approach these inner parts—what I call “exiles”—they often experience them as inner children who fit one of the three categories of troubled attachment: insecure, avoidant, or disorganized. Typically, once one of these inner exiles reveals itself to the client, their Self automatically knows how to relate to that part in such a way that it’ll begin to trust the Self. These inner children respond to the love they sense from the Self in the same way that abandoned or abused children do as they sense the safety and caring of an attuned caretaker. As parts become securely attached to Self, they let go of their terror, pain, or feelings of worthlessness and become transformed—a healing process that opens up access to a bounty of resources that had been locked away. When that happens, there’s a growing trust in the Self’s wisdom, and people increasingly manifest what I call the eight Cs of Self-leadership: curiosity, compassion, calm, courage, clarity, confidence, creativity, and connectedness. In other words, they return to a natural state of groundedness and embodiment. Attachment Theory assumes that healing occurs only when one person becomes a healthy attachment figure for another—a therapist for a client, one spouse for another, or a parent for a child—exhibiting the kind of engaged, active mindfulness we’ve been discussing. However, Selfleadership opens the possibility of a different kind of attachment-based healing within a person, which can lead to a deep sense of personal empowerment. The observer type of mindfulness meditation can reinforce the effects of this inner IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 62 attachment, so that therapy and meditation complement and feed each other. I’ve encouraged many of my clients to practice the observer type of meditation between sessions, and have found that their progress is hugely accelerated. The meditations help people practice separating from and accepting their parts, while accessing and trusting the mindfulness state, which increases clients’ ability for self-healing. The healing done in therapy, in turn, allows for deeper and less interrupted meditations. As clients become increasingly able to notice, rather than blend with, the wounded parts of themselves that are triggered as they go through their daily lives, they become clearer about what needs attention in therapy sessions. The Therapist’s Role With all this talk of self-healing, I don’t want to downplay the importance of the client’s relationship with the therapist. What does shift is the focus on the therapist from being the primary attachment figure to serving as an accepting container of awareness who opens space for the client’s own Self to emerge. To do this, therapists must embody their own fullest Self, acting as a tuning fork to awaken the client’s Self to its own resonance. To achieve this kind of embodiment, therapists must learn to be mindful of their own parts as they work with clients, recognizing that transference and countertransference are, at some level, a continuing behind-the-scenes dance as therapists and clients inevitably trigger each other. The inescapable reality of therapy is that, if we do our jobs well, clients will do all kinds of provocative things that repeatedly test us. They’ll resist, get angry and critical, become hugely dependent, talk incessantly, behave dangerously between sessions, show intense vulnerability, idealize us, attack themselves, and display astounding narcissism and selfcenteredness. Some of this is because they have parts forged by relationships with hurtful caretakers that are stuck in the past and, as they sense our open-heartedness, all that gets ignited. The Self-led therapist is basically issuing the client an invitation: “All parts are welcome!” From the darkest corners of their psyches, aspects of clients that others never see emerge in all their crazy glory, and that’s a good thing. When we aren’t overwhelmed by our own parts and can remain Self-led, clients can get to know what’s going on inside them, and healing emerges. But therapists aren’t Buddhas and regularly get triggered by the intensity of their interplay with their clients, whether they wish to acknowledge it or not. Fortunately, as you become increasingly familiar with the physical experience of embodying this mindful Self, you’ll be better able to notice the shift in your body when a troubled part hijacks you (you have a “part attack”). With that awareness—and lots of experience doing this kind of clinical work—comes the ability to calm the part in the moment and ask it to separate and let your fuller Self return. If I had a microphone in my head when I was treating certain challenging clients, you’d hear me saying repeatedly to IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 63 myself things like: “I know you’re upset, but just let me stay and handle this. Remember it always goes better if you let me keep my mind open. Just relax and trust me, and I’ll talk to you after the session.” On my good days, those words produce an immediate shift in my level of Self-embodiment—my heart opens, my shoulder muscles release, or the crowd of negative thoughts in my head disperses. My client suddenly looks different— less menacing or hopeless, and more vulnerable. Between sessions, I’ll follow up by bringing the parts that my client aroused to their own therapy, to give them the attention they need. In this way, our clients become our “tormentors” —by tormenting us, they mentor us, making us aware of what needs our loving attention. Working in this way can be an intense and challenging task, which regularly requires me to step out of my emotional comfort zone and experience “parts” in myself and my clients that I might otherwise wish to avoid. At the same time, on my best days, I feel blessed to be able to accompany clients on inner journeys into both the terror and wonder of what it means to be fully human. At those moments, I can’t imagine a more mindful way to practice the therapist’s craft. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 64 Beyond the Basics IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 65 Healing at a cellular level: IFS & Neuroscience Written by: Elyse Heagle, MSW, RSW The following section will present an overview of the intersection and integration of IFS theory and protocol with neuroscience. It should be noted that the correlations and connections presented here are brought forth to suggest strong links between neurological processes and the IFS framework. Some of these links have not yet been proven, and more research is needed in this area. There is a life-force within your soul, seek that life. There is a gem in the mountain of your body, seek that mine. O traveler, if you are in search of That, Don’t look outside, look inside yourself and seek That. - Rumi The building blocks Let’s begin by welcoming all the parts that have brought you to the neuroscience section of the manual; the ones that are here by sheer excitement, the ones that get dizzy at even the utterance of the word ‘neurobiology’, and the ones who may want to distract away at certain points. This portion has been written with all of you in mind, and in the spirit of allowing all systems to build a shared understanding of the intimate crossroads our Self and parts have with our biology. Let us walk down this road together, pausing when needed to attend to our parts, and towards an understanding that allows us to appreciate the integration of our body’s innermost processes with the theory of IFS. Now, we can start with the building blocks, otherwise known as our neurons (or nerve cells). Science Photo Library - KTSDESIGN/Getty Images IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 66 Neurons are the primary functional unit of the nervous system and are housed not only in the brain, but also within the body (Anderson, n.d.). They form a necessary highway that sends information through us, similar to how telephone wires transmit data to and from one another. Neurons are joined at synapses (the small gaps in between), which fire when they are stimulated by experience, and essentially grant us the capacity to absorb and respond to the world around us. The ability of our nervous system to respond to external and internal stimuli by reorganizing its structure and connections is called ‘neuroplasticity’, and the capacity of our brain to grow new nerve cells in response to this is termed ‘neurogenesis’ (Huebner, Anderson, & Schwartz,). Nerve cells connect together to form networks, which perform specific functions that give rise to thoughts, behaviors, and emotions (Huebner et al., 2013). In IFS we understand that these are functions of our parts, therefore we consider that symptoms represent neural networks, which represent our parts (Anderson, n.d.). As we move through life, various branches of our neural circuitry become activated depending on what we experience. Our sympathetic nervous system acts as an accelerator, kicking us into fight/flight/freeze states, or ‘hyperarousal’. While our parasympathetic system helps us to apply the brakes, allowing us to ‘rest and digest’. Steven Porges Polyvagal Theory posits that we have two branches within the parasympathetic system: a dorsal branch that becomes activated around threat or danger, carrying us into an extreme form of ‘shut down’ or hypoarousal, and a ventral branch or ‘smart vagus’ which is initiated when we feel safe and connected. The neural structure and connections within each of these systems are often deeply rooted in our early, formative experiences are organized/reorganized as we grow and experience the world. While systems can be understood as structural, Dan Siegal (Psychotherapy Networker, 2012) also presents a definition of the mind as an embodied, relational process that regulates the flow of energy and information, and the brain as the structure facilitating this function. Through this definition, parts use both the mind and the brain to utilize or access specific neural networks to express themselves (Anderson, n.d.). In our client’s systems we are often working with parts that have experienced some degree of IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 67 trauma, which has been transmitted through an internal circuit called the vertical network or the “bottom-up, top-down network” (Anderson, n.d.). In this network, information enters through the body, heading towards the limbic system containing the amygdala (the emotional integration center, where information is given significance), then to the prefrontal cortex (where information is processed), and back down again. Trauma inhibits this process when it floods the amygdala with sensory and emotional information about the difficult experience. This flooding can dampen the response of the prefrontal cortex, causing it to struggle to bring in reason and memory (Anderson, n.d.). This leaves the trauma survivor with high emotionality and high physicality, subsequently resulting in little ability to regulate (Anderson, n.d.). On a neurological level, this is one understanding of how trauma can become ‘stuck’ in the body and mind. As such, our parts too can become ‘stuck’ in the trauma experience, or the now-unintegrated network that has formed. Specifically, we may consider that protective parts and exiles live in the mind and use these networks to express themselves on a synaptic level (Anderson, Video). The dysregulation occurring on a neural level often mirrors what we sit with when clients become activated (Anderson, n.d.). For example, trauma reenactments (subtle or overt) reinforce the unintegrated neural network, thereby activating the parts stuck in the experience of the trauma. In other words, when a traumatized part blends with the client in such a way that the body and mind begins to re-experience the event(s), the trauma network becomes reinforced. This highlights the gift that IFS therapy can bring to trauma processing, as it places an emphasis on differentiating self from parts, thereby helping the trauma survivor be with the experience, instead of in it (Anderson, n.d.). When we help the client to unblend from a part and access Self energy, we are therefore promoting the healing/integration of the traumatized neural network. In IFS we hold goals of differentiating Self from parts, unburdening exiled or extreme parts to their natural form, and creating harmony within the system (IFS Institute, 2020). From a scientific lens, we can draw parallels between these goals and the concept of neural integration, or when our neural circuits are working together smoothly (Anderson, n.d.). We can theorize that Self expresses itself through accessing a critical mass of fully integrated neural networks (Huebner et al., 2013). At the same time, Self is not located in any one specific part of the brain or body (Anderson, n.d.). Self is a state of being that like parts, lives in the mind and is maximally integrated both internally and externally (Anderson, n.d.). It is no surprise that qualities of Self (compassion, curiosity, courage, etc.) are frequently reported during states of neural integration (Huebner et al., 2013). As such, the IFS therapist and use of therapist Self to guide the client system can be seen as helping to restructure (focus, find, befriend, witness) and reintegrate (retrieve, unburden) existing neural networks. You are in your body like a plant is solid in the ground, Yet you are wind. - Rumi IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 68 The IFS process through a neuroscience lens In IFS we go inside, and by doing so embark down a uniquely effective and holistic gateway. Down the path of Insight we meet our parts, intimately witness their experience, and effortlessly access Self energy. In typical talk therapy, we focus outside of ourselves, which is called exteroceptive awareness (Anderson, n.d.). In doing so, we primarily engage the prefrontal cortex, making it difficult to access the dysregulated neural networks that reside in body awareness (Anderson, n.d.). Interoceptive awareness, or insight, activates many different regions of the brain; specifically, with focusing inward the insula in the cerebral cortex is stimulated, which integrates body awareness (Anderson, n.d.). Evidently, we become much more connected to the emotional, physical, and spiritual sensations of our inner world, allowing a deep, Self-led knowing to occur. Accessing Self and parts creates space for transformative healing to occur in the system, the nature of which may be understood as mirroring the process of memory reconsolidation, a well-documented neurobiological process. Bruce Ecker (2015) defines this as, “…the brain’s innate process for fundamentally revising an existing learning and the acquired behavioural responses and/or state of mind maintained by that learning”. In other words, existing synaptic coding (target memory/part) is replaced by the new synaptic coding (updated information, transmission of information from part to Self in the system). When the memory/neural network (part) has been reconsolidated (unburdened), associated strategies (protectors) developed around it may no longer be needed in the same way (Huebner et al., 2013). Many clients who come to therapy are impacted significantly by implicit emotional learning, in other words, parts who have taken on beliefs or burdens about the world, themselves, and/or others within unconscious awareness (Ecker, 2015). Early experiences of vulnerability, suffering, and strong emotion may form in this way without awareness of learning anything at all (Ecker, 2015). Our parts absorb meaning from these experiences as absolute truths, enhancing the strength and durability of the burden(s) in our systems (Ecker, 2015). Exiles most commonly exist and express themselves within implicit neural networks/memories, which live in the right hemisphere of the brain, where there is a lack of time-sequence (Anderson, n.d.). Trauma treatment ultimately aims to make implicit memory explicit, promoting neural integration, and a reconsolidation of the traumatic material (Anderson, n.d.). The therapeutic process in IFS can be understood as facilitating reconsolidation through Selfto-part connection and healing. In the following section, neuroscience theory and the phases of memory reconsolidation will be explored in comparison to the process of IFS therapy. Find & focus To open an IFS session, we ask the client to go find the part in or around their body, noticing sensation, thought, energy, or anything else. The invitation to become IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 69 aware in this way activates the bottom-up portion of the vertical network, allowing sensory and instinctual experiences to enter conscious awareness (Huebner et al., 2013). This allows the client to access dysregulated neural networks, or target part(s), through attunement to their inner experience (Huebner et al., 2013). Once the client has found a target part, we invite them to focus, activating the top-down portion of the vertical network; here, the prefrontal cortex feeds back into the body, activating concentration, mindful focus, and attention (Huebner et al., 2013). This is similar to the ‘accessing’ phase in memory reconsolidation, where symptoms are identified and retrieved from implicit to explicit awareness (Ecker, 2015). Feel toward Once the target part is in focus, we elicit how a client feels toward the part, revealing how much Self energy is present. If we suspect that a part is blended with the client, we may consider scientifically that another neural network is operating (Huebner et al., 2013). We invite the part to ‘soften back’ in this moment, allowing clients to refocus. If the part does not agree to ‘soften back’ we work with it to address its concerns. A part refusing to step back may indicate that inhibition or fear response from the top-down network is resulting in an over activation of the threat detection system in the body (Huebner et al., 2013). Holding the client system in Self energy and addressing this activation with compassion reinstates cortical inhibition, the neurological process which is necessary when protectors agree to allow access to the exile (Anderson, n.d.). When sympathetically fear-driven networks are calmed in the presence of Self, the dysregulated neural network can be accessed and transformed. Befriend & witness Once we have permission to access the target part (protector/exile), the client’s Self befriends the part and begins to learn about its role and origins in the system. The befriending process is akin to a window into the implicit neural network that is driving the part to do what it does; during this process Self may learn of body sensation, sensory experience, or emotional information that is contained in the neural network being expressed by the part (Huebner et al., 2013). This is a continuation of making the implicit memory explicit, and remains a parallel process to the accessing phase of memory reconsolidation. As the Self-to-part connection persists, specific memories encoded in the neural network are brought into conscious awareness, allowing for a ‘narrative process’ to occur (Huebner et al., 2013). This conscious recollection of past experience promotes maximal neural integration; in other words, as the Self witnesses the entirety of the parts story, synaptic changes begin to occur (Huebner et al., 2013). Retrieve & unburden Ecker’s memory reconsolidation model discusses reactivation, mismatch, and erasure phases, similar to what occurs during the unburdening process in IFS. Once the target part feels like Self fully ‘gets it’ and that it is not alone, this allows the neural networks to be re-worked and rewired (Anderson, n.d.). Ecker’s model states that IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 70 synapses are destabilized and susceptible to change when we reactivate the memory without reliving it; in IFS we see this as being ‘with’ a part, rather than ‘blended’ (Anderson, n.d.). Moments of mismatch in reconsolidation manifest as, “…an experience of something distinctly discrepant with what the target memory “knows”…a surprising new learning or contradiction of information” (Ecker, 2015). In IFS, these moments may be demonstrated in the corrective experience that the exile receives with Self (Huebner et al., 2013). Erasure occurs when the memory has been revised with the new learning, and “the client experiences a profound release from the grip of a distressing acquired response” (Ecker, 2015). In other words, the neural network has demonstrated neuroplasticity to the extent that synapses have been unlocked at the existing emotional memory, not changing the autobiographical content of story but rather the emotional charge associated (Anderson, n.d.). In the unburdening process and once the story has been fully witnessed from Self, the exile is invited to release the burden it holds and take in the new qualities. Within the safe and loving presence of Self, we suggest that a similar neurobiological process occurs to that of erasure, intrinsically healing at the synaptic level and changing the neural network at its core (Anderson, n.d.). The new configuration A breath of love can take you all the way to infinity. - Rumi Once the system has released the burden, a natural progression occurs where the system reconfigures around the now-transformed exile; the neural network has transformed in such a way that previously acquired beliefs or behaviours may be extinguished in favor of the new information that has been consolidated (Ecker, 2015). This new configuration is different from counter active change, often employed in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, whereby a new neural network overrides the existing one, requiring maintenance in order to be sustained (Anderson, n.d.). Rather, the neural change that occurs in unburdening a part occurs at such a level that most often (with some exceptions) the change is permanent (Anderson, n.d.). The IFS therapist may ask the client to check-in with the part every day until the next session, which supports the neural integration, reinforcing the change that has occurred (Huebner et al., 2013). Once reconsolidation has occurred and neural networks have shifted, the part is not there in the same way, and the system experiences freedom to exist differently in the world. Although more research is needed in this area, it can be considered that IFS therapy heals us from the inside out at a cellular level, allowing us to be more ourselves in the world and free from the burdens deep within. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 71 References Anderson, F. (n.d.). Trauma, Neuroscience, & IFS with Frank Anderson MD: Module 1. Retrieved from IFS Institute Continuity Program. URL unavailable. Ecker, B. (2015). Understanding memory reconsolidation. The Neuropsychotherapist. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bruce_Ecker/publication/281571640_UNDERSTANDING_MEMOR Y_RECONSOLIDATION/links/569de33408ae00e5c98f0dcf.pdf Huebner, A., Anderson, F.G. & Schwartz, R. (2013). Neuroscience Informed Internal Family Systems Therapy. Unpublished manuscript. IFS Institute. (2020). The Internal Family Systems Model Outline. Retrieved from https://ifs-institute.com/resources/articles/internal-family-systems-model-outline Psychotherapy Networker. (2012). What’s the difference between the brain and mind? Dan Siegal explains. Youtube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DOV8sedmcYU&feature=emb_title Schwartz, R. & Sweezy, M. (2020). Internal Family Systems: Second edition. The Guilford Press. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 72 Polarisations Parts develop a complex system of interactions among themselves, polarizations and alliances, as parts try to gain influence within the system. Subtle managers are easily blended with the Self; important that the therapist is able to track client’s level and self-compassion and continual work to unblend. This requires very close tracking of client’s body positioning, facial and vocal expressions and content/reported experience. Firefighter-Manager polarizations can be difficult to differentiate. Helping clients to unblend from judgmental, critical or fearful protectors to accepting both “sides” creates more clarity and empowerment. When the therapeutic process seems “stuck” it is helpful to explore polarizations in the internal or external system. The polarization may first emerge as interference with the client being in Self as you work with a particular manager or firefighter. Our systems naturally seek to maintain balance. When one part is forced to adopt an extreme role, others attempt to balance it out by becoming more extreme in the other direction. Self of the client (and therapist if needed) can negotiate and mediate between the two extremes and reassure them that talking with one side won’t allow more power there; each can’t become less extreme until the other does. Often exiles that are fueling the protectors and their polarization will continue to create confusion or intensity until they are named and acknowledged (often more “circular” nature of this work). From Self, can ask each part what parts they may be protecting, who else protects them and how, which part or parts they dislike or fear, as well as what it is they are trying to accomplish for the client. Allowing each part space to be seen and heard by both the client’s Self and the part it is polarized with builds trust and compassion for the struggles of both parts. As each part experiences being understood by Self (and possibly the other part), they may become more willing to communicate with each other, appreciate each other’s differences even as they see they are on the same side, or basically are working toward something similar for the client. Often polarizations will shift when each part feels fully heard, understood and can have some appreciation for the efforts of the other part. The extreme states or roles of protector parts don’t really contain the suffering, but it is their polarity with one another that brings this forth; work with the protective system of parts is extremely relational and is all about building trust. Our role as therapist is to facilitate the relationship between the Self of the client and their system of parts as the fulcrum of transformation exists in that relationship. It is vital to fully IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 73 understand, acknowledge and build trust with the client’s protective parts so that they feel safe in allowing healing work to occur with the vulnerable exiled parts. Often when the client feels particularly stuck there is some sort of polarization going on, and most commonly these are between a Manager and a Firefighter, and very often they are protecting around the same issue. When we ask about parts who seem to be very different, for example, a “free spirit” part and a “responsible, self critical” part, it become obvious fairly quickly that we are dealing with a Manager/ Firefighter polarisation. The two parts will feel very differently about an issue, and the client will often feel stuck in their ability to move forward with a particular issue. Often the two parts will be very clear that they do not like one another. As always, both of the parts will have a preferred, less extreme role in the system which will become clear once we are able to help them and the exiles that they are protecting. Each of the parts would prefer to be in the less extreme role but usually feels unable to move into it until the other one is less extreme. It can feel like a catch 22, with both parts convinced that the other part is the extreme one, and they are just reacting to it. In order to work with the polarisation we have to elicit enough Self energy from the client so that (s)he is able to hold the space for the good in each part, and to be able to see that both parts want something valuable for the system. It often looks, on first glance, as if the Manager wants something good and the Firefighter is ‘sabotaging’ in some way, but when you spend the time to get to know the valuable role of each part, this changes. Often the Manager is very critical of the Firefighter, and shows up looking like a judgmental adult, and the Firefighter may be reacting in such a way that it looks like a teenager on first meeting. Both parts will have to be brought in somewhat from their extreme roles for the client to be able to work with them. Typically the two parts will have been in conflict with one another for a long time, and will be afraid that if they let the client listen to the other part then something bad will happen. The therapist has to help the client to be able to reassure whichever part is going to be asked to wait, at first, to tell its story, that the client’s Self will come back to hear the other part’s story and give them as much time as they gave to the first part. One thing that will often allow one part to wait while the other tells its story is to let both parts know that as we hear from them each, they may be able to come in from the extreme position that they feel so stuck in. The goal of working with polarized parts is to bring them out of extreme roles and create more harmonious relationships within the system. Often it can be helpful to ask the client to hold out their hands and put each part into a hand so that the client can more easily see both parts from the observing Self. While the client speaks to one part, the other part is listening, and after both have been heard they may be willing to have a conversation with one another. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 74 Legacy Burdens and Shame Patriarchy gives women a distorted version of their bodies and value, and makes men exile their sensitive parts. There are, of course, many other legacy burdens from the endemic patriarchal ideology of our culture; including (but not limited to) burdens associated with gender, sexual orientation, race, colour, religious practice, gender identity, ablism, age etc. Religious teachings that inject shame for “sinful” thoughts and drives. Also the pervasive beliefs associated with individualism: “You should be able to (control emotions, etc.)” worshipping willpower, increases shame. Other sources of shame It is virtually impossible to emerge from childhood without at least SOME shame. Shame about our existence, is called primal shame, which is a very powerful burden. For parts who believe they are unacceptable, unlovable, worthless, we add. insult to injury. First, they were rejected by others, then, we exile them in ourselves (managers), so they are rejected again. One of the most common ways of dealing with this, is introjection, taking on the caretaker’s energy into a manager to get you to behave. It feels the best way to survive is to mimic the parent to avoid being shamed. Or, the part may believe that if you are already being shamed by your critic, when your parents shame you, it won’t be so bad. Another strategy is to drop your confidence, never take risks, so you don’t get attacked or shamed. These are some of the positive intentions among our inner critics. Shame is self-perpetuating. We get the message from the outside world, then echoed in our inner world The more shame goes to the heart of our exiles, the more we need other parts, like firefighters, to protect us, which leads to behaviours that cycles more shame. This primal shame is at the root of many clients’ troubles. Our unsuccessful attempts to manage this can lead to more shame, in ourselves, and in relationships. Alternatively our strategy may be relentless activity, where we get constant evidence that we are valuable, but again, that evidence never touches our exiles, and so those feelings emerge whenever we pause. Unburdening Shame – when it doesn’t take Five reasons 1. Most commonly, we didn’t get the whole story witnessed, so it went back to show you the rest 2. The client didn’t follow up after the session, didn’t visit the exile enough and be sure it was ok, so the child felt abandoned and went back 3. There is some part of that burden that other parts are using to stay safe. So, those other parts use it to keep you safe. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 75 Example - If a child with sense of feeling worthless, unburdened, now feels valuable, but you didn’t work with the parts that are terrified to have you show up in the world as valuable now, they get scared and bring back the worthlessness. You may need to get permission from other protectors who are afraid that now you will get hurt as you show up in the world. 4. Something scary happened recently, and the protectors attribute the scary thing to your unburdening in therapy, so they bring it back. 5. When there is a “Self-like” manager part” trying to do this work. Then it fails, and gets pessimistic If the issue and feelings come back for a client, we ask “Ok, so let’s find out which of those 5 reasons this happened for?” Death Anxiety – another Core Exile I order to thrive children need to know they are wanted (i.e. have value) and are safe. When love is conditional the system will focus on producing behaviours most likely to meet the conditions. When an environment is unsafe and/or characterised by attachment wounding, the system may present with lifelong anxiety. If there is a part holding death anxiety, i.e. fear of annihilation it may get the system’s attention with ongoing “free-floating” anxiety. As in shame, this may be a core exile and the pervasive survival fear may track back to very early in life, including in utero and be held in implicit memory. Not all presentations of anxiety will track back to core exiles; however it is helpful to bear their existence in mind, and helpful to have worked with your own so that your own protectors do not inhibit the work. Working with core exiles requires compassion; the depth of their distress needs to be witnessed (and released) from that place and not simply from curiousity IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 76 Legacy Burdens Written by: Elyse Heagle, MSW, RSW This section will begin to describe the nature and impact of legacy burdens on our inner and outer systems. I use the word ‘begin’ because the discussion around legacy and how we carry it in our bodies, mind, and spirit, is far-reaching and deeply personal. When we open space to listen, our parts know their stories, and through the IFS process we work with them to remember who we really are. May this overview peak your curiosity to look within and without, and invite into action an exploration of what has been handed to us. be easy. take your time. you are coming home. to yourself. - the becoming wing, Nayyirah Waheed When we speak of legacy burdens, we speak of something that is different from the personal burdens that our parts take on from their direct experience. These are burdens that our parts absorb from experiences that did not necessarily happen directly to us (IFS Institute, 2020). With legacy, our parts take on the extreme beliefs, ideas, behaviours, and feelings of people around us or of those who came before (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). When we work with legacy burdens we are working with what has been passed down through families, cultures, and ancestral lineage (Gardener, 2020). Much like the personal type, these transferred burdens significantly organize and constrain our systems, especially because most often we receive them in early development (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Although not specifically explored in this section, we can also inherit legacy heirlooms or gifts from family/ancestors that do not constrain parts or exist as burdens in the system. Family Legacy As children, we are dependent on our parents for safety and therefore keen to remain accepted in the family system, so we learn to operate within it (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). We take on beliefs about ourselves, others, and the world that float, often unnoticed, in the family culture. For example, these may manifest as beliefs that ‘vulnerability is dangerous’ or ‘your value must be earned’. Legacy burdens gain power in our system because they are difficult to notice, we just assume ‘that’s the way it should be’ or ‘that’s just how the world is’. The burden becomes akin to a virus, which injects itself into our parts and drives the way they operate, often to extremes (IFS Institute, 2020). In kind, our protectors organize around the burden to help us manage risk. The virus metaphor is particularly potent in IFS because we understand that inherited burdens are neither the true essence of the part nor the ancestor; rather, the burden is separate from the inherent nature of the part and its ability to transform (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 77 It should be noted that many experiences when we are little can be understood as ‘first hand’ or personal, for example, a parent shaming a child and that child’s system taking on the shame as fact may be a personal burden (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). However, we can also hold curiosity around the nature of this transmission, opening space for Self to wonder if this legacy of shame may have also visited the parents when they were children themselves (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). There are many seemingly personal burdens that, when held in curiosity, open up to tell us of their legacy. Schwartz & Sweezy (2020) speak of transmission of burdens within the ‘law of inner physics’, which states that we relate to parts of other people, much like we relate to our own. For example, if growing up our parents learned that ‘children are meant to be seen and not heard’, they may banish the parts of themselves that speak up, stemming from the fear of being banished from their external family system. When parents exile the parts of them that are loud, this may also lead their system to exile ‘loud’ parts in others, and especially their own children. Our parts do this in service of maintaining safety in a world where the original burden still has influence. Numerous feelings can be exiled in families, and in doing so can cause us to lose contact with the parts who express them, and the natural value they add to our system in providing direction (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Cultural Legacy Not only do we find legacy burdens shape the nature of exiling in family lineage, but we can also uncover this in our country and cultural norms at large. Schwartz and Sweezy (2020) specifically outline the nature of legacy burdens held in the cultural mileu of the United States, but much of the same can apply to Canada as well. The legacy of burdens of racism, patriarchy, individualism, and materialism seem to be major forces contributing to the exiling of various people and groups, the authors state that this, “creates a greater capacity for contempt, rather than compassion” (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). The history of our country is undoubtedly saturated in racism; consider the broad history of race-based entitlement and subsequent genocides, deeming people seen as ‘other’ to be subhuman (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Today this entitlement rests in part within the realm of white-body supremacy, with a country of people and parts that have adapted to living under the influence of this belief system (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). In IFS, we open an invitation to recognize our racist parts, and listen to them instead of exiling their existence. Patriarchy and misogyny are another powerful legacy in our country, which includes social, political, and economic mechanisms that evoke male dominance over women. Dominant managerial groups control the narrative of ‘what is normal’ and thereby perpetuate shame and social control, ultimately serving to uphold this ideal; homophobia and transphobia can also be seen as linked to this deep-rooted legacy (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Interestingly enough, when we interview the protective parts who support this narrative, they often share that their goal is to prevent further shaming and ensure survival (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). In IFS we hold Self-led curiosity around the necessity of this narrative in the system, and perhaps for generations past, allowing the part to begin to separate from the influence of the burden and connect to its true nature. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 78 Individualism and materialism have also exerted influence over our country, perpetuating beliefs such as, ‘my failure is a personal fault’ and that ‘dominance is earned by those who work hard, likewise unearned by those who exhibit laziness and greed’ (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). In this cultural soup, we develop parts that express pride around dominance (economical, social, etc.) and exile parts of others that exhibit laziness or greed (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Epigenetics The secondhand nature of legacy burdens can also be understood through the neuroscience lens of epigenetics. This refers to a process where trauma (or legacy burden) is transferred across generational lineage through the genes of the traumatized individual or group (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Research has shown that our genes have the ability to change on a chemical level when environmental stressors are present, and this process is called methylation (Anderson, n.d.). This occurs when Methlyn groups attach to genetic material, and provide a molecular mechanism for gene-environment interactions, independent of a specific gene marker (Yehuda & Lehrner, 2018). This process essentially impacts the transcription of the protein, and can cause Post Traumatic Stress (PTS) reactions in offspring with no first-hand traumatic experiences (Anderson, n.d.). For example, offspring of Holocaust survivors displayed an increased prevalence of PTS symptoms in response to their own exposure to difficult events, which highly associated with maternal PTS (Yehuda & Lehrner, 2018). This brings to mind the impact of historical events such as colonization, slavery, and displacement trauma in many cultures and communities (Yehuda & Lehrner, 2018). The impact of past events cannot be understated, as chronic bias and fear towards a class of people often have origins in legacy, as well as shared feeling states and habits learned when in community with others (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). However, research has shown that good and nurturing environments can reverse the methylation caused by traumatic events (Anderson, n.d.). In IFS we offer a hopeful response to the impact of trauma, as we guide clients systems to connect to the loving, nurturing, and compassionate essence within the Self. The IFS Process As IFS therapists, we want to support a process where the part is able to let go of the burden and it’s constraining influence (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). Often, there are protective parts that organize around burdens, with strategies to ‘get over’ or ‘overcome’. In IFS, we do not bring any agenda to the unburdening process, we simply open space for the part to come to know that it can let go of what it holds in the presence of Self (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). If we sense that a part is carrying a legacy burden, we may ask exploratory questions, such as: “how much of [this] is your experience and how much was passed on to you?” “does anyone else you know share this belief/concern?” “when did you take on this burden?” IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 79 When a part lets us know that a portion of this belongs to someone else or that it has been with it “always”, we can begin to consider that we are working with a legacy burden. We may want to proceed with asking who the burden belonged to, proposing hope that we can also offer healing to the ancestral lineage in this process (Gardener, 2020). We then want to invite the part to separate what is theirs, and what is not, by asking: “what percent of this belief belongs to you, and what percent belongs to someone else?” (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). This answer may elicit a range of responses, but often the legacy burden comprises of 50% or more (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). We would then continue with: “would the part be willing to let go of the percentage that does not belong to it?” Sometimes, a part is reluctant to let go of the burden, sharing concerns such as: if I let go of that I will be letting go my connection to [my mother], I will be nothing without the burden, or that it is my duty to hold this burden for my [country/community] (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020; Gardener, 2020). We need to address the concerns directly, for example, we can offer that the heart connection between the mother and client will remain after the burden has lifted (Gardener, 2020). To address concerns of identity, we can guarantee the part will not disappear once the burden lifts, or that it can release it one drop at a time. Finally, to respond to concerns of loyalty, we can offer that the part can unburden and retain the memory of what has happened, but without the pain/emotional charge (Gardener, 2020). When the part is ready to unburden, we can ask it to find the burden/energy in their body and then send it back to the person/ancestral lineage from where it came (Gardener, 2020). We invite the burden to be passed back as long as it goes, to ancestors both known and unknown (Gardener, 2020). At the end, we can invite in healing energy/imagery to receive the burden and transform it (Gardener, 2020). Once transformed, qualities not available to the system while carrying the burden arise; these are often qualities of Self that can also be passed up through the lineage (Gardener, 2020). If a part is concerned about this process, another option is to send the burden into the light/air/fire/water. We may then continue to work with the portion of the belief that belonged to the part, the same way we work with personal burdens. As IFS therapists, it is also our responsibility to do the work in our own systems to uncover legacy burdens we hold. There are times when these burdens, if left beyond our awareness, will impact the safety of the session, as clients systems can often sense when we are blended with a part. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 80 References Gardener, K. (2020). Legacy Burdens [Video]. Retrieved from IFSCA Masterclass Series. Schwartz, R. & Sweezy, M. (2020). Internal Family Systems: Second edition. The Guilford Press. Yehuda, R. & Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry. 17(3): 243-257. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6127768/ IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 81 IFS & Addictive Cycles The inner struggle of addiction has been relentlessly pathologized and criminalized in North America, as evidenced by the plethora of managerial strategies aimed to extinguish ‘addictive behaviors’ and the years-long war waged on our firefighters, named “the war on drugs” (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). In IFS, we hold addiction in a different light, and in this section we will explore and describe the ways in which Self can build a relationship with all parts involved, ultimately unburdening the shame underneath (Krueger & Sykes, 2018). Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses, who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. - Rainer Maria Rilke Redefining the conflict Addiction can be understood as a power struggle or polarity occurring between extreme aspects of the personality system, sometimes referred to as an ‘addictive cycle’ (Sykes, 2006). The primary intention of each polarized part/group of parts is to protect the system from danger. This creates a dynamic of parts, each with their own strategies and roles, that fear the overload and overwhelm associated with deep seeded vulnerability or pain (i.e. exiles) (Sykes, 2006). When the IFS therapist begins to unfold the addiction from the identity of the client, suggesting that this is actually an interplay of parts, shame may begin to be reduced in the system (Krueger & Sykes, 2018). In fact, we hold this non-pathologizing stance in many aspects of the work, acknowledging the positive and adaptive intent of all parts, even those in extreme roles; this may sound like, “if you are using you have your reasons, we are here to look at the conflict inside…not take it away” (Krueger & Skyes, 2018). This is facilitated by entering the clients system from a Self-led place and not from our managers who may want to suppress the clients’ polarized parts (Krueger & Skyes, 2018). Parts who come with agenda to overturn protectors often only cause them to double-down on their role (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2006). So, collaborative approaches are employed, and ultimately the clients system decides how to navigate forward in the work. There are times that this paradigm shift can be shocking, especially for clients who enter therapy blended with critical parts who believe “[they] have to stop this!” or “what I am doing is wrong” (Krueger & Sykes, 2018). As IFS therapists we invite our clients to know the positive intent from the inside out. We are always listening for parts and reflecting back with curiosity. In the case of “what I am doing is wrong”, we hear from the critical part and of the part engaging in the behavior. Drawing our clients awareness and Self energy forward in separating the two, allows us to ask about the protective function of both parts directly, unfolding the origin and intent behind their strategy. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 82 The polarization within We may begin to work with someone by mapping their system and illustrating the addictive cycle of their parts. While mapping, we may come to know the polarization holding the tension in the system. On one side, we can find reactive firefighter parts, who use techniques such as: numbing, binge eating/drinking, drug or alcohol use, or dissociation (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). When asked directly, they let us know they are keeping the exiles at bay the best way they know how, by diverting the system from any awareness of emotional pain (Sykes, 2006). Quite often there are legacies of addiction in families, with firefighter strategies reaching back generationally (Krueger & Sykes, 2020). The short-term gain of ‘forgetting everything for awhile’ eventually gives way to manager backlash (Sykes, 2006). Manager parts often represent the other side of the polarity, using strategies such as: criticism, forceful disregard, and shaming in an attempt to create homeostasis after firefighters act out (Sykes, 2006). We can also see a short-term gain of ‘getting back on track’ and the system again assuming a faux state of balance. However, neither managerial nor firefighter strategies can prevent the triggering of the exile, as the world provides ample opportunities for the shame/pain beneath to get our attention. Not to mention, the cycle of the polarization itself also contributes to the shame reservoir, as each side never prevails for long, flooding the system with the shame or worthlessness held by the exiled part (Sykes, 2006). The IFS therapist holds space for both sides of the polarization to unfold and be appreciated from Self. As each side takes its position, they may share about feeling compelled into their role, unaware of another way to help the pain below the surface (Sykes, 2006). The Self of the IFS therapist guides the client system to recognize that there is a new option available now to heal the pain. More often than not, both parties resonate with this shared goal (to keep pain out of awareness), and allow access to the exile. Once we have access to the exile, Self can unburden it. In this process, it is important that the exiles story is fully witnessed, as a partial unburdening can lead to relapse. It may also be true that multiple exiles must be unburdened before the system can reorganize. The therapists’ Self supports the wisdom of the clients system in this process. If relapse does occur, it may be that exiles previously unknown/dormant have come forward or the healing was not complete, and the polarization may resume its role (Krueger & Sykes, 2018). The therapist addresses the relapse with the same curiosity and compassion as previously explored. Making peace with our warriors Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love. - Rainer Maria Rilke IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 83 Once we have deeply witnessed and facilitated the healing of our parts, we are called to make peace with our inner warriors, once polarized and at war. Recognizing the position they held inside of the system as being of service of keeping the pain out of awareness calls us to honor their service. With the pain of the exile no longer at risk of flooding, firefighters and managers are both freed up to assume their natural role in the system. Ultimately, in supporting our clients to explore their addictive cycle with curiosity, we create the possibility for deep healing of what has been so profoundly hidden within. References Krueger, M. & Sykes, C. (2018). The Voices of Addiction: Winter Module [Video]. Retrieved from IFS Continuity program. Skyes, C. (2006). Manager & firefighter polarizations: an internal family systems view of the addictive cycle. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58e13ba9db29d6c9b31ede41/t/5e399111a1fc225432b34e7 1/1580830993866/Manager+and+Firefighter+Polarizations.pdf IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 84 IFS & Couples Written by: Elyse Heagle, MSW, RSW “It is in the practice of Self-compassion that it becomes possible to love freely and courageously, thriving in intimate connection with others and ourselves” - Toni Herbine-Blank In the monolithic mind paradigm, when we work with a couple, we are working with two beings. However in IFS, while we are often working with two clients, we are actually holding space for a multitude of parts within the pair. Often, these consist of several parts engaging in repetitive and predictable cycles that make up the pattern of conflict (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). The IFS couples therapist aims to assist both partners in healing their inner worlds and embodying more Self-led connection to their partner. We hold the hope that as this different inner relationship unfolds, the partners will experience more choice and spaciousness in their reactivity, being able to be more themselves in the face of future conflict (Herbine Blank, 2018). The following section will outline broad strokes of Intimacy From the Inside Out (IFIO), a method pioneered by Toni Herbine-Blank. IFIO is a psychotherapeutic process rooted in the theory of IFS that aims to heal and improve relationships. The invitation inward We want to begin by assisting the couple to flesh out the nature of their dynamic. This may involve tracking a ‘sequence’, or a predictable and repeating pattern of behavior between protective parts (Herbine Blank, 2018). This process of tracking how protective parts interact within each system involves looking and listening to how the parts are strategizing around the deeper feelings of the exile (Herbine Blank, 2018). As the IFS therapist begins to see parts speaking to parts, they may share their observations with the couple. This helps the client(s) to recognize their protective parts in-action, and assists the individual in getting curious about the unmet needs existing just beneath this protective shield (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). In doing so, we often come to learn that protective parts are attempting to restore connection or get a need met that is held by an exile. However their strategies are ineffective, as they are focused on looking outside of the system for their healing. Once clients begin to recognize exile-protector pairings, and build relationship with the protectors themselves, the vulnerability/pain/unmet need of the exile may be revealed. The therapeutic process of unfolding this story within the pairing often begins by focusing on one person and inviting them to turn their attention inward (Herbine Blank, 2018). Offering exploratory questions such as, “what do you notice inside of you?” or “what do you hear yourself saying about you, or about your partner?” (Herbine Blank, 2018). We avoid the question of “how do you feel about [your partner]” because this tends to shift the focus and blame back onto the other persons system; we want to keep the focus inward (Herbine Blank, 2018). Then, the therapist may ask, “what is your first impulse?” or, what is the first thing you want to do when [part] feels this way, and then we ask what it is like when their partner responds to that behavior (Herbine Blank, 2018). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 85 Finding space and choice The therapist holds space and curiosity for the partners’ Self to come into relationship with the protector(s), eventually understanding what the protector is afraid will happen if they don’t react/do what they do (Herbine Blank, 2018). Through this, as with the basic IFS protocol, we validate the protectors’ attempts, seeing the well-intended plight to keep the exiles intensity at bay. Often, as one client works with their inner system, their partner also witnesses this for the first time, seeing the participating partners’ reactivity from a new lens. During this process, the therapist aims to check-in with the witnessing partner to see if they are able to stay present to what is unfolding (Herbine Blank, 2018). Here, we stay close to the creed “all parts welcome”, allowing the witnessing partner to speak from whatever part may be present, and then helping them unblend if necessary (Herbine Blank, 2018). Once the participating client becomes more aware of their inner world, they may be invited to practice speaking for what is going on inside of them, instead of from it (Herbine Blank, 2018). When we speak for a part, we bring more Self energy into the exchange, and practice responsible self-disclosure; this allows protectors to trust that Self can lead the system (Herbine Blank, 2018; Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). When both partners take ownership for their parts and the origins of the protective strategies, they begin the important process of differentiating internally so they can differentiate externally (Herbine Blank, 2018). The therapist would continue to work with each system to unburden the exiles, allowing even more freedom for choice, and space to recognize that everyone has a core need to be heard and understood (Herbine Blank, 2018). Subsequently, relational unburdening can occur in the space where one partner bears witness to their own exile internally, while the other brings love and compassion externally; a remarkable and corrective experience within both the internal and external worlds (Herbine Blank, 2018). Heart centered communication As each partner’s system receives healing, the need to look outside for validation diminishes, and more room is made for error and forgiveness in the couple relationship (Herbine Blank, 2018). In other words, as the polarity of each individual’s system relaxes and heals, the couple naturally shifts into a more flexible state; for example, saying “no” does not create a survival threat and both can negotiate their own needs (Herbine Blank, 2018). Not surprisingly, when the couple relates from Self-led energy rather than parts, they tend to remember why they connected in the first place (Schwartz & Sweezy, 2020). It is important to note that throughout this process the IFS therapist is engaged in maintaining a safe triangle – which includes both partners and themselves (Herbine Blank, 2018). The maintenance of safety lies not only in the parts work process, but also within the therapists’ own system. So, we ask ourselves continuously, “am I able to stay present?” simultaneously doing in the inner work of noticing and asking space from parts that may polarize with what is present in the couple. Ultimately, the IFIO process invite clients to connect with what has been inside all along, opening up a new frontier of possibility in the relationship, and sending the resounding message, “I can be here for you because I have a Self” (Herbine Blank, 2018). IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 86 References Herbine Blank, T. (n.d.). IFS Continuity Program: Intimacy from the Inside Out. Retrieved from IFS Institute Continuity Program. URL unavailable. Schwartz, R. & Sweezy, M. (2020). Internal Family Systems: Second edition. The Guilford Press. IFSCA Course Manual www.IFSCA.ca 87