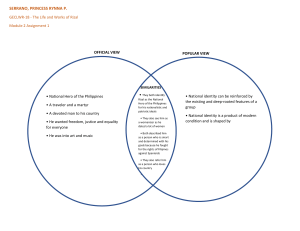

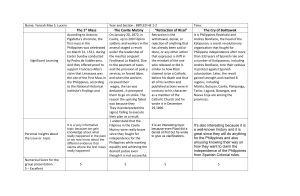

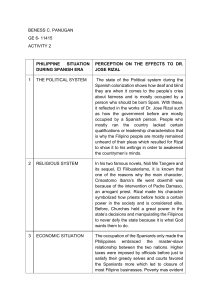

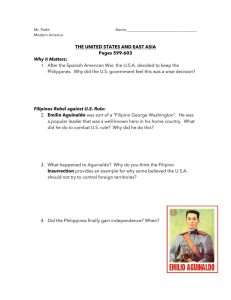

Module 2 The Philippine Political and Socio-Economic Struggles in 19th Century Module Overview: This module will have a deeper understanding of the various political and socio-economic struggles in the 19th Century, particularly in the Philippines. These situations and events are important to discuss since it has greatly influenced the actions of Rizal towards his fight against the Spaniards and some of these issues are still relevant up to the presentday situations. Module Objectives: 1. Describe the influence of the different economic and political issues in the 19th Century in Rizal's life and works 2. Explain Rizal's involvement in the significant events in Philippines during the 19th Century Lessons: Lesson 1 The 19th Century Philippine Economy and Society Lesson 2 Agrarian Disputes Lesson 3 Emerging Nationalism Lesson 4 Imagining a Nation Lesson 1 The 19th Century Philippine Economy and Society Objectives: At the end of this section, you should be able to: 1. Discuss the changing economy and society Of the 19th century Philippines; 2. Rellate these situations to Rizal's life in the country; 3. Describe the role of the Chinese mestizos in the Philippine economy; 4. Reflect on the struggles of social stratifications at present-day through journal writing; Introduction Welcome to another discussion of our lesson in Rizal 101. In this lesson, we will explore the political and socio-economic situation of the Philippines during the 19th Century. Activity SAMAL BRIDGE TO PUSH THROUGH? Have you heard the news about the Davao-Samal bridge project? This issue has been going on for decades since this will greatly impact the economy and commerce in the Davao Region. What do you think are the advantages and disadvantages if ever this government project will push through? Share your ideas with the class. Analysis If ever the Davao-Samal Bridge will be pushed through, sure enough, there will be changes in the life and economy Of the Samalenos and Davaoenos. This is the same as the Spanish government's economic changes implemented in the Philippines, which will be discussed in this lesson. Here are some questions that will be relevant to our discussion later on: 1. How can economic changes affect society? 2. How can traders influence the economy as a whole? Abstraction Changing Landscape of the Philippine Society and Economy Many scholars regard the nineteenth century in the Philippines as a period of significant transformation. Huge economic, political, social, and cultural currents were felt throughout this time. Change, on the other hand, had its beginnings in the previous Century. The monarchy in Spain had changed hands from the Habsburgs to the Bourbons by the late eighteenth century. Spain's colonial policies were re-calibrated under the new government, which had an impact on the Philippines. Bourbon policies and reforms were implemented to revive the profitability of colonies such as the Philippines. José de Manila - Acapulco Galleon Trade Basco y Vargas, the first governor-general to visit the Philippines under the Bourbon mandate, arrived in the Philippines in1778. By the time Basco arrived, the Galleon Trade, the main economic institution in the Philippines, was already a losing enterprise. As Spain sought ways to salvage the dwindling economy of the empire, the global wave of industrialization became a silver lining. As many imperial powers in Europe and the West were undergoing industrialization, increased demand for raw materials presented an opportunity to look into the agricultural potential of the Philippines. Thus, it was Viewed that the transformation of the economy towards being export-oriented, harnessing the agricultural products that could be yielded from the archipelago, was the way to go. To better facilitate the envisioned reorientation of the economy, Basco established the Royal Philippine Company in 1785 to finance agricultural projects and manage the new trade between the Philippines and Spain (and Europe) and other Asian markets. These changes, however, were met with a lukewarm reception. Resistance also came from various sectors like the Catholic Church that was not receptive to the labor realignments entailed by the planned reforms and traders still holding on to the Galleon Trade. It also did not help that the Royal Philippine Company was fraught with issues of mismanagement and corruption. As Basco pushed for the reforms, he lifted a ban on Chinese merchants that reinvigorated internal trade; initialized the development of cash crop farms; relaxed certain policies that allowed the gradual opening of Manila to foreign markets; and established the Tobacco Monopoly to maximize the production of this export good. At the turn of the nineteenth century, global events continued to have an impact on the Philippines. By 1810, the Spanish empire had been shaken by the Mexican War of Independence, eventually resulting in the loss of valuable Latin American colonies. As a result, the Galleon Trade, which had become a source of anxiety in the Philippines, ended. As the Philippine economy hung in the balance, policies were re-evaluated, and by 1834, Manila had been opened to international trade with the closure Of the Royal Philippine Company. As a result, foreign merchants and traders arrived in Manila. Eventually, they settled there, taking over funding and assisting the developing agricultural cash crop, export-oriented economy. Some of the most significant investments were made by British and American entrepreneurs who established merchant companies in Manila. In the Philippines, rapid economic expansion began to flow through cash crops. By the first part of the nineteenth century, cash crops such as tobacco, sugar, cotton, indigo, abaca, and coffee accounted for most of the Philippines' exports. As cash crops became the colony’s primary source of wealth, land value became more apparent. Land ownership and management became a challenge when the provinces began to cultivate income crops. Farmers were feeling the effects of the economy, while hacenderos seized the opportunity. When a minor landowner, for example, needed cash, he would enter into a pacto de retroventa, a sale agreement that guaranteed he could repurchase the land at the same price he sold it for. However, due to the economy's everincreasing demand and the sale's renewals, it became increasingly difficult to buy back the land, further burying the farmers in debt. They would eventually lose their land and were forced to work as tenant farmers or kasamå. Aside from this method, land acquisition was also made by land-grabbing. Inquilinos arose as the rising economy necessitated better land management. They rented property and sublet it to smaller farmers. These causes would alter the social stratification in the countryside, which, as the following chapter will demonstrate, was not without tensions and contestations. The Chinese and Chinese Mestizos The Chinese and Chinese mestizos were two segments that gained substantially from the shifting economy. Philippine natives have had trading links with the Chinese since pre-colonial times. During the height of the Galleon Trade, Chinese products made up the majority of the goods traded. The Spanish were distrustful Of the Chinese due to the flood of Chinese communities in the Philippines. These sentiments resulted in harsh official measures toward the sangley, ranging from greater taxes to mobility restrictions with the construction of the Chinese enclave (the parian) to outright expulsion programs. On the other hand, the Chinese proved to be "essential outsiders" in the colonial economy and society of the Philippines. Although the Spaniards were cautious of the Chinese, they recognized their role in the economy's survival. The Chinese enlivened the economy, from the products loaded on galleons to the rise of retail trade. They were eventually absorbed into colonial society, resulting in intermarriages with indios and the birth of Chinese mestizos. Throughout the Spanish colonial period, Chinese mestizos played an essential part in the economy. They influenced the evolving economy in the nineteenth Century by buying land, amassing riches, and establishing businesses. Impact on Life in the Colony As previously said, economic developments triggered social, political, and cultural changes for example, the new economy required a more educated populace to meet the growing demand for a more professionalized workforce to manage trading activities in Manila and other major cities. This desire prompted the colonial government to issue an edict in 1836 requiring all towns to establish primary schools to teach the inhabitants how to read and write. It eventually resulted in the passing of an education decree mandating free primary education in 1863. Eventually, several schools arose in the nineteenth century to meet the growing demand for additional experts. During this time, schools such as the Ateneo Municipal were founded. The administration was also able to increase bureaucratization and streamline colonial governance due to the complicated structure of the expanding economy. Manila became a potential destination for those seeking better prospects or desiring to flee the worsening circumstances in the farmlands as it grew as a commerce center. Internal migration has increased at an alarming rate, causing various issues. For one thing, people flocked to trading hubs like Manila. Overcrowding resulted in problems with living quarters, sanitation, public health, and an increase in crime. Two, people's constant migration made tax collection even more difficult. To address these concerns, Governor-General Narciso Claveria issued an 1849 decree encouraging colonists to establish surnames. The colonial administration allocated surnames to citizens using the catalogo de apellidos and banned people from changing their names at will. The colonial authority sought a better surveillance system by enacting policies such as registration and ownership of a personal cedula bearing one's name and address. The guardia civil was eventually established to aid in the better execution of policies. As the emerging economy provided new opportunities for the colonial state, it also led the state to become more regulated and assertive. Renegotiating Social Stratification The impact of the expanding economy on Philippine society was felt. As a result, social interactions were redefined, and social stratification was renegotiated due to changing dynamics. New lines were created with the following socioeconomic strata as the mestizo population grew in importance. Social Stratification durinq the Spanish Colonization in the Philippines Peninsular - People who are pure-blooded Spaniards born in the Iberian Penins Insular - Pure-blooded Spaniards born in the Philippines Mestizo - People born of mixed parentage. They can be either: • Spanish mestizo — (Spanish parent and native parent) • Chinese mestizo— Chinese rent and native arent) Principalia - Pure-blooded natives that are wealthy and are supposedly descend from the kadatoan class Indio - Pure-blooded native in the Philippines Chino infiel - Non-Catholic pure-blooded Chinese In the nineteenth century, as the Spaniards lost economic power, they reassert authority based on race. This problem was exacerbated by the growing principalia and mestizo populations, who recognized their critical role in society as economic movers and facilitators. Throughout the Century, the renegotiation continued as the mestizos and principalia elite desired social respect that the pure-blooded Spaniards had continually denied them. These prosperous mestizos and principalia members continued to build economic and cultural riches. They also took advantage of opportunities to pursue further education in the Philippines and Europe. These actions increased their social relevance because it was from these ranks that nationalist articulations would emerge. Check it out! A lot of changes in the society and economy had occurred in the Philippines during the 19th Century. One of which is the decline of the Galleon Trade, but what is something special about this trade? What made it flourish before the 19th Century? Check out this video link to know more. In addition, get to learn more about the concept of social stratification and how it affects every society across the globe. Enjoy watching! https://wmv.voutube.corn/watch?v=8 ik78uilbE — The Galleon Trade https://www.Y0utube.corWwatch?v=6zv12fcSnFY — What is Social Stratification Application After accessing the links provided above, in your Ouipper Classwork, click on the classwork entitled Module 2 — Lesson 1 — Application (The 19th Century Philippine Economy and Society) and answer the following question the same as the one presented here. Write a reflection paper about the current social stratification situation in our country. Refer to the following guide questions below. (7pts. — content, 5pts — relevance of ) examples, 4pts- organization of ideas, 2 pts. — grammar and technicalities 2 pts. — punctuality). Answer the questions a one reflection paper. DO NOT answer separately. Write in 8-10 sentences. 1. What is social stratification? 2. Is there a wide gap in social stratification in the Philippines? Defend your answer and provide examples. 3. How can social stratification affect Philippine society? 4. Can social stratification be avoided? Why? Closure Glad that you have just finished the first lesson in the module! We shall now proceed to the next lesson. References De Viana, A. et al. (2018) Jose Rizal: Social Reformer and Patriot: A Study of His Life and Times. Rex Bookstore Wani-Obias, R. Mallari, A. and Reguindin-Estella, J. (2018). The Life and Works of Rizal. The Life of Jose Riza/. pp. 59 — 71. C & E Publishing, Inc. Quezon City. Diokno, M. (1998). The end of the galleon trade. Kasaysayan Series Vol. 4: Life in the Colony, pp. 7-25. Hongkong: Asia Publishing Company Limited. Lesson 2 Agrarian Disputes Objectives: At the end of this section, you should be able to: 1. Discuss the history Of the agrarian situation Of the Philippines during the Spanish period; 2. Explain how the Calamba Agrarian Issue reflected the agrarian conflicts in the 19th Century; and 3. Evaluate the agrarian issue during the Spanish period and the present day through a Venn diagram. Introduction Welcome to another lesson in Rizal 101. We shall now explore the agrarian situation of the Philippines in the Spanish Era. This has a great impact on Rizal's struggle to fight against the colonizers. Let usproceed! Activity DYING BREED OF FILIPINO RICE FARMERS? In modern Filipino society, careers and jobs have greatly developed since technology innovation in the 2000s. This has resulted in the decline of young Filipino farmers in the rural areas Of our country. But what has caused such phenomena? Check out this video below and share your opinions on what you have watched. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v—lAvlVpnnNN4 — Infographic Video About the Dying Breed of Filipino Farmers. Analysis Earlier farmers also experienced the struggles of our Filipino farmers during the Spanish Era. In our lesson in agrarian disputes, here are some questions that will be relevant to our discussion later on: 1. What will happen if farmers will be deprived Of their rights and privileges as tillers of the land? 2. Is it important the farmers should have their lands to till on? Abstraction Brief History of Friar Estates in the Philippines The friar estates date back to land grants given to early Spanish conquistadors who arrived in the Philippines in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Around 120 Spaniards were handed grants, often made up of a large tract of property called a sitio de ganado mayor (1 ,742 hectares) and smaller sections of land called caballerias (measuring 42.5 hectares). For three reasons, the Spanish hacenderos were unable to develop their holdings over time. The Spanish population in the Philippines was, first and foremost, a transient one. After serving in another country, it was typical for Spanish administrators to return to Spain. Second, until the latter portion of the Spanish colonial period, the market for cattle goods offered by haciendas remained modest. Finally, the Manila-based Galleon Trade offered greater financial advantages and attracted more Spaniards. The religious organizations quickly took over the work because the Spanish hacenderos lacked the enthusiasm and inclination to develop their territories. The religious orders acquired land in a variety of ways. Often, Spaniards seeking spiritual advantages donated the property. Estates that had been severely mortgaged to the ecclesiastics were sometimes subsequently purchased by the religious organizations themselves. According to records, several prominent Filipinos contributed to establishing the friar properties through donations and sales. Despite these techniques, Filipinos had a widespread conviction that the religious orders had no legal title to their estates and had obtained them through usurpation or other illegitimate means. Nonetheless, ecclesiastical estates in the Tagalog region grew to the point where they accounted for almost 40% of the provinces of Bulacan, Tondo (now Rizal), Cavite, and Laguna by the nineteenth century. During the early decades of Spanish colonial authority, the estates' preoccupations were diverse. The properties were used mainly as cow ranches and subsistence crop farms in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Rice and sugar became vital sources of wealth for religious organizations, especially throughout the nineteenth century, as they were the primary commodities produced in the haciendas. The haciendas' agrarian interactions evolved throughout time. The social organization of the haciendas in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was predominantly made up of lay brother administrators at the top and cultivated tenants below. Although the lay brother administrators were directly responsible to the heads of their religious organizations, they were given considerable latitude in making administrative decisions. On the other hand, tenants were expected to cultivate the land and pay an annual rent, typically a specified quantity of harvest or, later in history, money. A rising economy centered on agricultural produce exports ushered in transformation by the mid-eighteenth century, gradually establishing an inquilinato system. An individual, known as a canon, rented property for a fixed annual price under this system. The inquilino or lessee was also required to provide personal services to his landlords in addition to the rent. If the inquilino fails to meet these standards, he may be expelled from the country. In most cases, the inquilino would then sublease the land to a kasamå, or sharecropper, who would then be responsible for cultivating the soil. The result was a three-tiered system, with landowners at the top, inquilinos in the center, and sharecroppers at the bottom. By leasing the property to an inquilino, the religious hacenderos were relieved of the social obligations that came with direct contact with the sharecroppers, as the inquilinos were now the ones who dealt directly with the kasamå. On the other hand, the sharecroppers benefited from the agreement because their labor duties to the religious estates permitted them to avoid the Spanish government's forced labor requirements. The disadvantage of this type of arrangement was that two non-cultivating groups further reduced the sharecroppers' revenue. The leftover income would be split among all sharecroppers after the inquilino paid his rent to the religious hacenderos and deducted hi own share. The haciendas would become sources of contention among the Spanish religious hacenderos, inquilinos, and sharecroppers as the social structure and land tenure patterns changed. It's no surprise. then, that when the Philippine Revolution erupted in 1896, abuses on friar estates were frequently cited as one of the main reasons for the uprising. Hacienda de Calamba Conflict Prior to 1759, little is known about the Hacienda de Calamba, other than that a group of Spanish laymen owned it. Don Manuel Jauregui, an impoverished Spaniard, surrendered the lands to the Jesuits in 1759 to be permitted to live in the Jesuit monastery for the rest of his life. The Jesuits would only be able to claim ownership of the country for eight years before being exiled from the Philippines by King Charles Ill on February 27, 1767. As a result of the expulsion, the government confiscated Hacienda de Calamba and other Jesuit holdings and placed them under the Office of Jesuit Temporalities. In 1803, the government sold the land to Don Clemente de Azansa, a Spanish layman, for 44,507 pesos. When he died in 1833, the Dominicans paid 52,000 pesos for the Hacienda de Calamba, including 16,424 hectares. Many families from nearby towns had moved to the hacienda in pursuit of economic prospects by this time. Rizal's family were among the families who arrived at the hacienda, and he went on to become one of the property's main inquilinos. Although other families leased property in Calamba, Rizal's family leased one of the largest leased lands, measuring around 380 hectares. Sugar was a major crop planted in the hacienda since it was in high demand on the global market. Because these estates provided so much riches to Rizal's family, it was only natural that the family was concerned when the conflict broke out in 1883. The friars were collecting rents without giving the regular receipts, according to Paciano Rizal, who wrote in 1883. The renters could not pay their rent two years later because the rent had allegedly doubled while sugar prices remained low. The Dominicans declared the lands unoccupied and allowed citizens from neighboring cities to take over the leases as a punishment for the tenants' failure to pay the rent. The friars’ position was undermined because just a few outsiders replied to the Dominican's invitation. With the exception ofour or five renters, the majority of residents were spared from eviction. Mariano Herboso, Rizal's brother-in-law, maintained the complaints against the friars, notably complaining about the yearly increase in rentals, defective irrigation systems, and inability to give receipts. These issues were compounded by the fact that the price of sugar on the global market was continuing to fall at the time. Paciano pondered returning his properties to the friars and clearing ground elsewhere because the situation had worsened. The colonial government wanted a report on the hacienda's income and productivity from the tenants in 1887, suspecting that the Dominicans were avoiding paying their taxes. The renters obeyed and provided a report, but they also included a José Rizal petition. The petition listed several complaints against the hacienda owners, including a complaint about rising rent. Some renters began withholding rent as a form of protest. In 1891, the friars began evicting tenants who refused to pay rent as a measure of vengeance. Those who continued to oppose the friars were eventually banished. Rizal's parents, brother, and sisters were among those who were exiled to remote parts Of the nation. Despite Rizal's efforts to overturn the Philippine courts' ruling, his family's exile would only be removed if another governor-general issued a decree. The incident had a profound impact on Rizal, and the growing sorrow resulting from it was represented in his second novel, El Filibusterismo. Check it out! Want to know more about the Calamba agrarian crisis? Check out these links for further knowledge! • Rizal's agrarian dispute - https://opinion.inquirer.net/54539/rizals-agrarian-dispute • The Hacienda de Calamba Agrarian Problem (1887 — 1891): A Historical Assessment - http://haciendadecalamba.blogspot.com/2012J06/ Application After accessing the link provided above. in your Ouipper Classwork, click on the classwork entitled Module 2 — Lesson 2 — Application (Agrarian Disputes) and answer the following question the same as the one presented here. Compare and contrast the agrarian disputes between the Spanish Colonization and present-day agrarian problems. Use a Venn diagram to present your results. (20 points — 8pts — Content, 6 points — relevance of key points, 4 points — organization of ideas, 2 points — punctuality) Closure Glad that you have just finished the second lesson in the module! We shall now proceed to the next lesson. Lesson 3 Emerging Nationalism Objectives : At the end of this section, you should be able to: 1. Discuss the causes and effects of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny; 2. Explain the conflict between Filipino secular and Spanish priests; 3. Showcase fair judgement towards the two perspectives of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny. Introduction In this lesson, we will discuss the events that happened in the 1872 Cavite Mutiny and the execution of the GomBurZa, which fueled Jose Rizal in his quest for freedom of the country from the Spanish colonizers. Activity FILIPINOS FOR NATIONALISM. Look at the pictures below. Can you determine these historical events that showcase the nationalism of Filipinos throughout history? Analysis The same as the pictures shown above, we will talk about the growing nationalism during the 19th century that greatly influenced Rizal's life and works. Here are some questions that are relevant to our discussion. 1. How can one's action for the love Of country influence his peers and fellow countrymen Abstraction Aside from this lesson, you may also check the PDF file attached in your Quipper Portals the Material under Module 2— Lesson 3 — Emerging Nationalism. Cavite Mutiny On January 20, 1872, about 250 Filipino troops and workers staged an insurrection at a Cavite arsenal. During the revolt, eleven Spaniards were killed, but the uprising was put down within three days by an instant assault conducted by government forces. A decree issued by Governor-General Rafael de Izquierdo was frequently considered as a cause of the rebellion. The directive said that the arsenal personnel would no longer be free from tributo and polo, a benefit they had previously enjoyed. On the other hand, Official versions claimed that the uprising was part of a larger movement to depose the Spanish government and declare independence. According to official sources, the mutiny organizers expected close to 2,000 troops from regiments based in Cavite and Manila. The plan was to start the revolution after midnight in Manila, with rebels lighting fires in Tondo to draw the police' attention away from the city. The rebels in Cavite would then receive a signal in fireworks and lay siege to the arsenal. In truth, the mutiny in Cavite began earlier that evening, with many of men who had committed support defecting and swearing allegiance to Spain. The revolt failed, and the Spanish government utilized the incident to repress growing calls for a more liberal government. Filipino secular priests were among those who demanded reforms. A little historical background on missionary endeavors in the Philippines will be discussed first to understand how Filipino secular priests became involved in the Cavite Mutiny of 1872. Secularization Movement The efforts of two sorts of clergy: regular priests and secular priests, were significantly responsible for the introduction and development of the Catholic religion. Because of their high standards of discipline and asceticism, the regular clergy, whose jurisdiction was delegated to their elected prelates, were better prepared for missionary work. Their mission was to bring the faith to the people, convert them, and build religious communities. The Augustinians, who arrived in 1565, the Discalced Franciscans, who came in 1578, the Jesuits, who arrived in 1581, the Dominicans, who arrived in 1587, and the Augustinian Recollects, who arrived in 1606, all took up this mission in the Philippines. Priests who "live in the world," on the other hand, made up the secular clergy. They were not members of a religious order and were under the authority of bishops. Their primary responsibility was to oversee religious groups and, ideally, carry on the regular clergy’s work. In other words, whereas regular clergy were responsible for introducing the faith and establishing religious communities, secular priests were responsible for managing the parishes. The missionary work in the Philippines, on the other hand, was a one-of-a-kind situation. In other Spanish colonies, established parishes saw regular clergy replaced by secular priests in the administration of religious institutions. Regular clergy in the Philippines remained parish administrators far into the nineteenth century. In the Philippines, two subjects were particularly heated among the clergy. The first point of contention concerned episcopal visits. Pope Adrian VI issued the omnimoda bull in 1522, allowing regulars to administer the sacraments and operate as parish priests without the local bishop's authority. On the other hand, this bull ran counter to reforms enacted by the Council of Trent (15451563), which said that no priest could care for the souls of laypeople unless he was subordinated to episcopal jurisdiction, which was frequently exercised by visitations. The regular clergy Often thwarted the implementation 01 the reforms in the Philippines, despite King Philip Il being given discretionary power to do so. The regular clergy claimed that allowing the visitations would subject the community to two sources of power, the bishop and the provincial superiors, who could issue opposing commands at any time. They intended to avoid violating their oaths of obedience to their superiors by resisting the episcopal visitations. Serious attempts to implement the visitations, on the other hand, were frequently thwarted by regular clergy who misused their positions by retiring and leaving the churches unattended. This type of circumstance was especially devastating during the early stages of Christianization when the government was frequently forced to give in to the requests of the regular clergy due to a lack of secular priests. The second problem concerned the administration of the parishes. Because there were few secular priests to whom the parishes could be passed on in the early stages of Christianization, regular priests kept control of the parishes. However, beginning in the late seventeenth century attempts to develop and train Filipino secular priests were strengthened, and by the nineteenth century, they accounted for a growing proportion. Despite this, the regular clergy frequently questioned, if not outright refused, the secular clergy's access to congregations. The regulars gave one reason: the Philippines was still an active mission, en vive conquista espiritual, with some non-Christianized communities. As a result, they would say that the Filipinos were not prepared to be handed over to secular clergy. Another reason was economic, with regulars refusing to give up parishes that provided them with significant revenues. However, the regulars' refusal to abandon the parishes was primarily due to their belief that the Filipino secular clergy were unfit and incapable. Worse, some secularists were seen as possible leaders of any future separatist movement. These statements would elicit a significant reaction from the secular clergy. Fr. Mariano Gomez, parish priest of Bacoor, and Fr. Pedro Pelaez, secretary to the archbishop, drafted expositions to the government on behalf of the secular clergy in the mid-nineteenth century their efforts were fruitless. When the subject of secularization was no longer limited to considerations 01 merit and competence, the debate took on a new tone in the 1860s. By 1864, the issue had also evolved into one of racial equality. Fr. Jose Burgos was at the vanguard 01 the fight for equality between Spanish and Filipino priests. Execution of Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora On Governor-General Izquierdo's instructions, numerous priests and laymen were detained due to the insurrection in Cavite. Fathers Jose Burgos, Jacinto Zamora, Jose Guevara, Mariano Gomez, Feliciano Gomez, Mariano Sevilla, Bartolome Serra, Miguel de Laza, Justo Guazon, Vicente del Rosario, Pedro Dandan, and Anacleto Desiderio were among the priests jailed in the days that followed. Gervacio Sanchez, Pedro Carillo, Maximo Inocencio, Balbino Mauricio, Ramon Maurente, Maximo paterno, and Jose Basa were among the laypeople. In Guam, these Filipinos were sentenced to various terms of exile. Burgos, Gomez, and Zamora, the three priests, on the other hand, were sentenced to death by garrote. Check it out! The 1872 Cavite Mutiny and the execution Of the GomBurZa gave Rizal a great influence in his fight against the abusive Spaniards. However, this significant historical event presented two sides of the story: The Spanish and Filipino perspectives. Click on this video link to know about point-of-view of the two sides: httpswwww.youtuoe.cowwatCh?v=3PDYOFonTQU&t=93S Application After accessing the link provided above, in your Quipper Classwork, click on the classwork entitled Module 2 — Lesson 3 — Application (Emerging Nationalism) and answer the following question the same as the one presented here. Answer the questions in 3-5 questions. 5 points each. 1. What is the importance of the 1872 Cavite mutiny and the GomBurZa execution in the life and works of Jose Rizal? 2. After knowing the two perspectives of the 1872 Cavite mutiny, which side will you pick on and why? 3. If you were Rizal, will these events also motivate you in fighting against the Spaniards? Why? Closure Glad that you have just finished the third lesson in the module! We shall now proceed to the next lesson. Lesson 4 Imagining a Nation Objectives: At the end of this section, you should be able to: 1. Explain the purpose Of the Propaganda Movement; 2. Discuss Rizal's contribution to the movement; and 3. Show critical thinking in using propaganda techniques in writing. Introduction Now that we are in Lesson 4, we will look into the involvement of Jose Rizal in the propaganda movement and how the movement influenced him in Europe. Let us proceed! Activity PEN MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD? Do you agree that words written by the pen can inflict so much damage compared to the use of a sword? Defend your stand and provide real-life examples. Analysis When Rizal arrived in Europe, he became associated with groups of Filipino reformists that pushed their agenda through literary works and propaganda. Here are some questions that will be relevant to our discussion later on: 1. How can articles and documents influence the opinion of the masses? 2. Is this method of revolution of Rizal effective against the Spaniards? Abstraction The Circulo Hispano-Filipino, an organization, led by a creole named Juan Atayde, was the first attempt to bring Filipinos studying in Spain together. It received backing from Spaniards who sympathized with the Filipinos. In 1882, the Circulo started publishing a bi-weekly journal called Revista del Circulo Hispano-Filipino, but the newspaper and the organization only lasted until 1883. Despite the Revista del Circulo Hispano Filipino closure, Filipinos in Spain continued to write and publish. In 1883, a newspaper named Los Dos Mundos was published to seek equal rights and advancement for the overseas Hispanic colonies. Although it is unclear whether Filipinos started the publication, Filipinos such as Graciano Lopez Jaena and Pedro Govantes y Azcarraga worked on the crew. Other Filipinos, such as Rizal and Eduardo de Lete, wrote essays about the Philippines' sociopolitical and economic developments. During the publishing of Rizal's debut novel, Noli me Tångere, in 1887, another newspaper. Espana en Filipinas, was founded in Madrid with the help of Filipinos, creoles, and mestizos. Because of evident differences and internal squabbling among its workers, the newspaper was also short-lived. With the publication of the journal's last issue, a stronger Filipino community formed, unified in its commitment to continue working for Filipino rights. The Filipino community in Barcelona began planning the production of a new newspaper in January 1889. Mariano Ponce and Pablo Rianzares were among the early financial contributors. Graciano Lopez Jaena, on the other hand, volunteered his skills as an editor. Marcelo H. del Pilar, who had recently arrived from Manila, also joined the attempt. On February 15, 1889, the newspaper La Solidaridad published its debut issue. •To resist every reaction, to block all retrogression, to applaud and support every liberal notion, to defend all advance," the team said in its inaugural article. The publication demanded reforms such as Philippine representation in the Cortes, press freedom, and an end to the practice of exiling citizens without due process. Because it was the only one of Spain's overseas provinces without parliamentary representation, the magazine emphasized issues concerning the Philippines. La Solidaridad frequently published articles about Spanish politics, friar attacks, and Philippine reforms. Sections were also assigned to receive and print letters from foreign correspondents, all of which discussed current events. Aside from political and economic themes, the monthly also provided room for literary pieces to be published. The newspaper's readership grew throughout time, and its roster of writers grew as well. José Rizal, Dominador Gomez, Jose Maria Panganiban, Antonio Luna, and prominent Filipinist scholar Ferdinand Blumentritt were among those who eventually submitted papers. Other Filipinos who wrote articles did so under the guise of a pseudonym. Del Pilar progressively assumed a more active part in the paper's operation. Despite his title as an editor, Lopez Jaena spent much of his days at cafés and was notorious for his inability to work for long periods. When del Pilar chose to go to Madrid, he took the newspaper with him. On November 15, 1889, the first edition printed in Madrid was published. The periodical announced a change of editorship a month later, with del Pilar taking over. By 1890, two of the most influential members of the Filipino community in Spain had begun to take opposing positions on Philippine issues. Rizal was a firm believer in bringing matters closer to home to serve the country better. It was necessary to communicate with Filipinos rather than Spaniards. On the other hand, Del Pilar was a skilled politician. He believed that efforts to persuade Spanish authorities and officials should be pursued since this was the best way to improve Filipinos' desired improvements. Things came to a climax in 1891 when Filipinos in Madrid advocated electing a leader to unite their community during a New Year's Eve feast. Rizal consented to the plan, although del Pilar was hesitant at first. Despite this, voting took conducted, with three inconclusive ballots on the first day and two more inconclusive votes on the second. Rizal did finally become the leader of the Philippines, but only thanks to Mariano Ponce's machinations. Rizal eventually sensed his victory was fleeting and left Madrid a few weeks later. Rizal stopped contributing articles to La Solidaridad after this and concentrated only on the composition of his novels. Only until 1895 did the monthly continue to be published. The newspaper published its final edition on November 15, 1895, due to a shortage of funding and internal strife. "We are persuaded that no sacrifices are too small to win the rights and freedoms of a nation afflicted by slavery," its editor, del Pilar, wrote in the final issue. Check it out! The Propaganda Movement by the Filipinos made a significant impact in piercing through the so-called invincible authority and power of the Spaniards during the 19th century. Learn more about this movement by clicking on this video link: httpsffww-w.voutube.com/watch?v= N OXiRV8YE. Enjoy watching! Application After accessing the link provided above, in your Quipper Classwork, click on the classwork entitled Module 2 — Lesson 4 — Application (Imagining a Nation) and answer the following question the same as the one presented here. Answer each question in 3-5 sentences and explain it briefly—5 points for each question. 1. What the purpose Of the Propaganda Movement? 2. Did they have a great impact in the Philippines? Defend your answer. 3. Choose an article on the internet (news article, blog, Vlog, social media post) that you think uses propaganda to inform the public. Please provide the link, take a screenshot Of it, and explain why you think it is a propaganda article. References • De Viana, A. et al. (2018) Jose Rizal: Social Reform.er and Patriot: A Study of His Life and Times. Rex Bookstore • Wani-Obias, R. Mallari, A. and Reguindin-Estella, J. (2018). The Life and Works of Rizal. Imagining a Nation. pp. 98-107. C & E Publishing, Inc. Quezon City Closure Well done! You have a complete grasp of Module 2 — The Philippine Political and SocioEconomic struggles in the 19th Century. Get ready to learn Module 3, Rizal's Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. SUMMARY During the 19th century, a lot has changed in the situation Of the Philippines under Spanish rules in terms of political and socio-economic aspects. These situations eventually led to gradual changes that tried to break through Spanish authority and power walls in the previous centuries. Consecutive struggles and conflict experienced by the Spanish Empire have affected their control of Galleon, forcing them to open up Manila for international trade in the industrialization boom among European countries. However, because of the economic policies imposed by the Spaniards on its Philippine economy, it has worsened the situation Of the Filipinos, especially in the agricultural sectors where raw materials and products have increased its demand in the world market at the expense of harsh conditions experienced by these farmers. This situation has widened the gap in the social stratification in the Philippine society under the Spaniards. Moreover, the disputes in agrarian issues between farmers, tenants, and their landlords have also spread throughout haciendas in the rural areas. The Church uses its influence to impose authority among the Filipinos. As a result, these events became factors that awakened the minds of the Filipinos to step up and take action against the Spanish abuses in the country. Incidents such as the unforgettable 1872 Cavite Mutiny created a domino effect in which the Spaniards thought that suppressing the mutiny would enforce greater authority towards the Filipinos. Still, in reality, it served as the starting fire of the upcoming revolutionary and reformist actions committed by the Jose Rizal and the llustrados in Europe and the Katipuneros in the homeland.