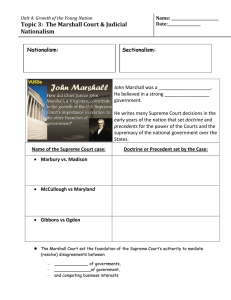

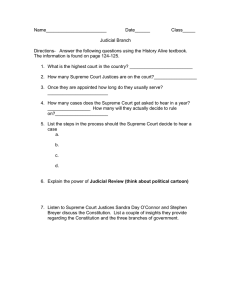

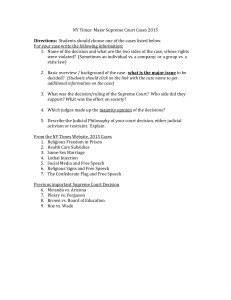

A Report on Supreme Court Decision-Making 1 The Supreme Court’s history is filled with evidence of the Court, not as an umpire, simply making decisions based on objective truths, but of a court that acts in ways that are politically expedient for the court and generally reflect the values of the times. In cases of the Court’s infancy, the Court made decisions cementing the role of the Court as a body, patrolling difficult waters between being passive and being overruled. Both outcomes would have made the Court look weak and thus had to be avoided, even when legal reasoning said otherwise. The Court has consistently folded under political pressure in times of war and when there is a perceived war against the Court. Generally, the Court decides cases within the general window of political thought. The guiding law of the Court is not an objective rule. The Court seems to follow a slightly altered version of the oft-quoted Martin Luther King Jr. statement, that version being, “The arc of the legal universe is long, but it bends towards political expediency and moderation.” I. Introduction to Constitutional Law To understand some of the difficulties faced by the Court, an examination must first be made of the philosophical and historical circumstances that underlay its development. For one, there is the concept of “higher” law. As well, the disagreements of the framers as to the purpose of the Courts leave textual and intentional evidence lacking. Finally, further analysis will be made as to the actual text and its ambiguities that lie within. The role and purpose of the court were hotly debated even at its inception which leaves the purpose of the Court generally questionable thus making strict Constitutional analysis difficult, if not impossible. The Court is innately tied to the concept of “higher” law, the ideas arising from theories of fundamental law. While there was much thought surrounding fundamental laws, the Americans who were involved in framing the Constitution, “[infused] it with interpretations 2 drawn from their own unique experience” (McCloskey, 5). The court must then be representative of “higher” law, a protector of people and a restraint on government power. This is similar in form to the highest courts of England, setting precedent and ruling on government authority. However, when considering the Court’s place there arises a question. Is the Court supposed to be the only authority on the Constitution or is the power to be shared among the branches? For this question, we must turn to the disputes between the framers as to the role of the Court. While there are nominally two separate groups when discussing framers, the visions of the Court are much more varied than that. First, the Democratic-Republicans, exemplified by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. The belief in the will of the people drove Jefferson, which placed within him a general concern about the power of the government to hold back the sentiment of the citizens. However, he generally thought that over the long run, the wishes of the people cannot be held back from being realized. (McCloskey, 6-7). “But James Madison…[expected] the Supreme Court to disallow laws that clearly contravened the Constitution” (McCloskey, 5). As this paper goes on, I believe the Jeffersonian view to be justified with how the Court has acted. On the other side, there are the Federalists. The main thinker who exemplifies the Federalist positions on the Court is Alexander Hamilton. As noted in McCloskey, “Alexander Hamilton, certainly hopes that the justices would act as general monitors, broadly supervising the other branches of government and holding them to the path of constitutional duty” (McCloskey, 4). This debate, existing not only between parties but also between members of parties, lays out a contested view of the role of the Court even in the minds of the founders of our nation. These contested views are displayed in the ambiguities in the language of the Constitution’s section on the role of the Court. Article III, Section II outlines many of the cases 3 that will be in the purview of the Court. The portion of most consequence reads, “The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority;--to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls;--to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;--to controversies to which the United States shall be a party;--to controversies between two or more states;--between a state and citizens of another state;-between citizens of different states;--between citizens of the same state claiming lands under grants of different states, and between a state, or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens or subjects.” (CR, 332) The language leaves much of the specific roles of the court ambiguous. What does the statement, “extend to all cases…arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made”? The difficulty parsing what exactly the purview of the Court is has led to endless debate about what is and isn’t expressly the role of the Court. A further discussion should be made into the thoughts of Alexander Hamilton as it pertains to the Court. In Federalist 78, Hamilton refers to the Supreme Court as “the least dangerous branch” as it had power over neither “the sword or the purse” (CR, 305). This makes some of the discussions about the often political, moderating decisions of the court understandable as a feature and not as a bug. The judiciary is supposed to have to consider the actual application of their rulings as it comes to whether the executive will actually carry out their rulings. II. Establishing Legitimacy The ambiguities of the Court thus left the Justices in the precarious situation of existing in a role that lacked substantial concrete goals. The Court in its infancy had to navigate to avoid exposing itself as weak and inefficient, while also not being seen as an arm of either the 4 legislature or executive branches. The establishment of Judicial Review is the model for the political navigations that Marshall was required to make. The continuing cases which establish judicial review over not only the cases for the Federal Government but also over state governments. This incremental movement developed the court out of its infancy while Marshall wrote opinions avoiding major objections from official rebuke from those who could damage the courts. The doctrine of Judicial Review arose from the case of Marbury v. Madison. This contains some of the most astute political maneuverings and displays the conceptions the court makes when dealing with issues. In Marbury, Marshall had to ensure that his order did not seem like the Court was being entirely guided by the political pressure from Jefferson, but also not to issue an opinion which could be ignored by Jefferson showing the weakness of the Court. Marshall did this by granting that Marbury was owed his commission but stated that the Supreme Court did not have Constitutional Power to grant him his writ of mandamus. Thus, the act that had attempted to expand the purview of the Court was unconstitutional. The legal reasoning is shaky, but the political maneuvering is top class. It sets the precedent for not only judicial review, but also for how the Court deals with difficult times. The Court in times of difficulty will issue statements to not look like pushovers while yielding to the wishes of those who could weaken the Court. The lesson taken in Marbury seems to come from the failure from the decision in Chisholm v Georgia. In an early Court decision, the Court held that citizens of a state could sue a different state than he was a resident in. This decision was so reviled that it was almost immediately overturned with the passage of the 11th Amendment blocking this from occurring. The decision made less than 10 years before Marbury taught the Court not to challenge public 5 sentiment because when it goes against it, then public opinion will lash back and delegitimize the Court. As the Court moved from establishing its role as a federal restrictor and conducting a judicial review over the federal government to establishing judicial review over states. These moves were slow and deliberate by Marshall. For awhile the court held back as Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party threatened the Justices with impeachment. The return to judicial power and the beginning of the application of the Court to states was the case of Fletcher v. Peck. The holding off of any major decision until the threat of impeachment subsided shows another way that the Court’s application of the law is heavily dependent on the political situation in which they are existing. With further application to the states through the cases of Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee and Cohens v. Virginia. With the application of the Supreme Court to the states, Marshall moved on to one of the most important cases in Supreme Court history. The case of McCulloch v. Maryland was another brilliant Marshall decision which led Federalist thinkers to concede that the Court should have invalidated an act of Congress, thus implicitly stating that the Court had the power to do so. (McCloskey, 44-46). However, Marshall would not be around forever to steer between these difficult distinctions. As the Court moved into the next era, it would be faced with no fewer political questions, however, the discretion of the Court was now accepted as legitimate by most all. III. Times of War for the Court, In Two Ways However, there would be a decision that would alter the Supreme Court’s legitimacy leading into a crucial time in American History. The case of Dred Scott v Sanford would challenge the court’s legitimacy right before the outbreak of the Civil War. The case came to the ruling that black peoples could not be citizens of the United States. This destroyed many 6 conceptions people had about the court due to Marshall’s expert maneuvering. The issue of slavery and emancipation was crucial at the time and the ruling took away the claim that the Court ruled on legal matters, not political ones. (McCloskey, 62-62) The decision broke the barrier for many who had previously seen the Court as legitimate. This issue of Court legitimacy severely affected the Court’s power to make rulings in the upcoming Civil War. However, there was another factor that affected this power. Lincoln, emboldened by the Dred Scott decision, challenged the Court’s power and whether or not he would follow their orders. Thus, the Court during the Civil War exercised great discretion whenever a case came across their bench dealing with the Civil War. The unilateral move by Lincoln to blockade Southern Ports without Congressional approval was upheld in The Prize Cases. (CR, 60-64). The case in Ex Parte McCardle was held from the decision as Congress withdrew jurisdiction and this withdrawing of jurisdiction was upheld by the Supreme Court. The Court showed extreme leniency when considering cases surrounding the Civil War, granting Lincoln powers that generally do not appear in the Constitution. As it comes to war powers of the President, one case sticks out. It is the case of Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer. During the Korean War, steelworkers were going on strike. However, President Truman decided as a preemptive act to nationalize the steel industry under the President’s role as commander in chief. This was immediately met with legal action and Truman’s seizure was ruled unconstitutional. So, why in this case was power not granted to the executive? In McCloskey, it is argued that the relative unpopularity of the President would have made retaliation unlikely on Truman’s part. Thus, the court was free to rule in a way less lenient than normal in times of war. (McCloskey, 147). While leniency is granted, there are 7 conditions in which the considerations of moderation and political expediency are not favorable to a decision. This is generally the case when the US is in times of war, after World War II even this instinct to defer to the military remained. Korematsu v. U.S. is the prime example of such. In the case, the decision to arrest Korematsu was upheld and the legitimacy of internment camps was not challenged. Instead, the Court deferred to military authority and Congressional approval. (CR, 212-213) As stated by Justice Black in his opinion, "Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire, because the properly constituted military authorities feared an invasion of our West Coast and felt constrained to take proper security measures, because they decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast temporarily, and, finally, because Congress, reposing its confidence in this time of war in our military leaders—as inevitably it must—determined that they should have the power to do just this" (CR, 213). The political pressure to uphold Korematsu was strong at the time and the Court decided as they usually do in times of pressure, by folding. However, as time moves on it has rightfully claimed its place in a hall of shame. However, the Court is not only deferential in times of actual war. Rather, whenever there is a perceived war on the courts, the Court usually accedes to the figures making the threat. Following the Civil War, the Court moved to look mainly at Commerce Clause cases and restricting the ability of the Government to hold regulatory power over private enterprise. This continued until the ascendency of FDR and his New Deal. One by one, the court attempted to strike down the laws as fast as they came before them. At this point, FDR had seen enough and was moving forward in an effort to pack the Court with new justices who would uphold his 8 policies. The Court soon had an amazing change of mind regarding the policies of the New Deal. The decisions of Justice Robert Owens soon fell consistently in line with the liberal wing of the bench, whereas for many preceding decisions he had sided with the Conservatives. While the intention of this switch is disputed, it is easy to see that the result was the Court changing with the time and making a move that kept the Supreme Court intact, as it was. (McCloskey, 108-119) This folding to political pressure from the Presidency has been noted twice before, with Jefferson’s hostility to the courts and Lincoln’s challenge. This establishes a pattern of political decision making to uphold the court as it stands, even at the cost of consistency or powerful decisions. As well, cases during wartime consistently favor governmental arguments as was shown in the cases of The Prize Cases and Korematsu v. the United States. The court does not usually push heavily against the currents of public opinion as they fear an unpopular opinion will impinge upon their legitimacy. IV. Counter-Arguments and Counter-Counter-Arguments Some will counter that the Court must not consistently think about Political pressures when considering cases such as Brown v. Board of Ed. or Roe v. Wade. As laid out in the section on Brown in McCloskey, the decision did not come out of the blue. Over the past several years, there had been specific developments which had created differences in the era. With the integration of troops under Truman, the entrance of Jackie Robinson into baseball, and the rise of the Soviet Union, the world looked much different over a short amount of time. While racist sentiments still rang true in the South, times were changing, and the courts recognized that. The rise of the Soviet Union called many to protest domination in many places, as McCloskey notes the rise of the Soviet Union was noted specifically by the Solicitor General in his brief. (McCloskey,148) 9 However, even outside the specific considerations of changes in society, we can see again Court hesitancy to do anything past moderate changes. The specific phrase “with all deliberate speed,” (CR, 224) as the key element of Brown’s requirements for rollout was specifically tailored to give the maximum discretion to federal judges in deciding how the desegregation effort was going. The politics of the time and the methods by which the case was put into effect both display a political consideration and moderation by the Court. Another decision which seems like an important departure for the Court from public opinion comes in the form of Roe v. Wade. However, McCloskey notes that much of the response to Roe began later, he notes changes that occurred in 1978 and 1980 (5 and 7 years after the decision respectively). The Court must have also been aware that the previous Griswold decision was widely popular (found the banning of contraceptives in violation of the right to privacy in marriage) and thus may have seen this further extension as a similar act. It is not an intention to play down the importance of the decisions in Brown or Roe, rather it is to show that the Court still undertakes some level of thought as it pertains to case decisions. The decisions in these two cases are simply examples, there are many other cases which seem like extreme departures, however, when looking at them critically, they can be seen as in line with a thesis of political consideration and moderation. V. Conclusion If the court, as it hopefully has been shown, truly is an actor of moderation and political maneuvering, then what is its purpose? The Court as moderator of political trends is not an unwelcome assessment of the Court’s role. By staying within reasonable bounds of the political discourse, the Court may not always jump immediately to a correct decision, but it also will most 10 likely not jump all the way to disastrous ones. While sometimes it has made awful decisions, Plessy v. Ferguson, Korematsu v. US, and Dred Scott v. Sanford, the Court has, generally, stayed within a certain range of general political thought. The Court may not be a fully independent umpire simply calling balls and strikes, but it is an important moderator against political temperaments which would be instituted infringing on natural rights. While for many, the Court is seen as an implicit defender against oppression due to its decision in Brown, the Court has shown more consistently to be an actor of moderation. While the Court’s inability to act quickly in the face of what some see as blatant injustice may be frustrating, it is a feature of the design, not a bug. By acting as a slight correction device for the path of the country, the Court has solidified itself as a mainstay and a given in US political life. The positive about the thesis, that the Court takes political factors into consideration, is that Court decisions are forever enshrined as fact and permanent rule. It will most likely take decades for the Court to overturn injustices, as in the case of the overturning of Plessy, but with enough change in political opinion, the opinions of the Courts can be changed. The considerations Justices make include moderation and public opinion, while they may not act as fast as some hope, there is a silver lining. The moderation of the Court allows for continuity in the law and a general call on the citizen to fight for causes they believe in. The Court will not be there to change its mind all on its own, rather it requires organizing and changes in political opinions as it pertains to these important societal issues.