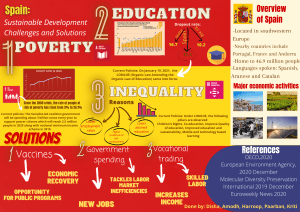

Global Population Growth & Sustainable Development Report

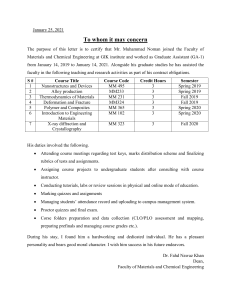

advertisement