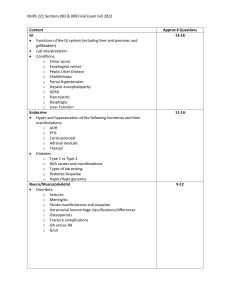

Contents

I. Pulmonology............................................................................................................... 6

1) Acute bronchitis, tracheobronchitis, bronchiolitis .......................................................................... 6

2) Chronic bronchitis, pulmonary emphysema, COPD ...................................................................... 7

3) Respiratory failure – pathophysiology and clinical features ........................................................ 11

4) Bacterial Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)....................................................................... 13

5) Non-Bacterial Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) ............................................................... 13

6) Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) ........................................................................................... 13

7) Treatment of pneumonia ............................................................................................................. 16

8) Purulent diseases – bronchiectasis, pulmonary abscess ............................................................ 19

9) Pleural effusions .......................................................................................................................... 22

10) Pulmonary tuberculosis ............................................................................................................. 23

11) Pulmonary embolism (PE)......................................................................................................... 28

12) Diffuse parenchymal pulmonary diseases (DPLD) (AKA interstitial lung disease – ILD) .......... 30

II. Cardiology ............................................................................................................... 32

13) Diseases of mitral valve: Mitral stenosis ................................................................................... 32

14) Diseases of mitral valve: Mitral regurgitation (AKA mitral insufficiency).................................... 33

15) Diseases of aortic valve: Aortic stenosis ................................................................................... 36

16) Diseases of aortic valve: Aortic regurgitation (AR) .................................................................... 37

17) Endocarditis .............................................................................................................................. 38

18) Pericardial diseases- classification. Pericarditis. Cardiac tamponade. ..................................... 41

19) Myocardial diseases: Myocarditis.............................................................................................. 45

20) Myocardial diseases: Cardiomyopathies ................................................................................... 47

21) Acute heart failure (HF) ............................................................................................................. 50

22) Treatment of acute HF .............................................................................................................. 52

23) Chronic congestive heart failure ................................................................................................ 54

24) Parameters of cardiac function in CHF. Treatment of Chronic heart failure.............................. 57

25) Ischemic heart diseases: classification. Stable angina pectoris – clinical features, treatment .. 61

26) Acute coronary artery syndromes: acute myocardial infarction w/ST segment elevation ......... 64

27) Acute coronary artery syndromes w/out ST segment elevation: unstable angina pectoris,

myocardial infarction w/out ST segment elevation .......................................................................... 66

28) Conductive disturbances. Treatment of conductive disturbances. ............................................ 68

29) Rhythm abnormalities: Supraventricular arrhythmias – classification, hemodynamics, clinical

features ........................................................................................................................................... 73

30) Treatment of supraventricular arrythmias.................................................................................. 79

31) Rhythm abnormalities: Ventricular arrhythmias......................................................................... 82

32) Treatment of ventricular arrythmias........................................................................................... 85

33) Anti-arrhythmic drugs: classification, dosage ............................................................................ 87

34) Hypertension (HT) ..................................................................................................................... 89

35) Arterial hypertension – treatment .............................................................................................. 91

36) Acute rheumatic fever. Rheumocarditis .................................................................................... 93

37) Chronic cor pulmonale (AKA pulmonary heart disease) ........................................................... 95

38) Aortic diseases: aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm, Takayasu disease.................................... 96

III. Rheumatic diseases ............................................................................................. 101

39) Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) ........................................................................................................ 101

40) Ankylosing spondylitis (spondyloarthritis, Bechterev’s disease) ............................................. 103

41) Reactive arthritis (formerly known as Reiter syndrome), Rheumatic fever, Reiter’s syndrome,

Lyme disease ................................................................................................................................ 105

42) Rheumatic fever ...................................................................................................................... 106

43) Psoriatic arthritis ...................................................................................................................... 108

44) Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) AKA lupus.................................................................... 109

45) Systemic sclerosis (SSc) (AKA systemic scleroderma) .......................................................... 111

46) Polymyositis, dermatomyositis ................................................................................................ 113

47) Vasculitis/vasculitides – clinical features and classification .................................................... 115

48) Henoch-Schönlein purpura (AKA IgA vasculitis) ..................................................................... 117

49) PAN/Polyarteritis nodosa ........................................................................................................ 118

50) ANCA associated vasculitis..................................................................................................... 119

51) Large vessel vasculitis – Horton disease, Takayasu’s arteritis, Buerger disease ................... 120

52) Anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS) ......................................................................................... 123

53) Polymyalgia rheumatica and fibromyalgia ............................................................................... 124

54) Gout (podagra) ........................................................................................................................ 126

55) Osteoporosis ........................................................................................................................... 127

56) Osteoarthritis (OA) .................................................................................................................. 129

57) Treatment of rheumatic diseases w/biological and biosimilar drugs ....................................... 131

58) Humoral immunity changes in rheumatic diseases ................................................................. 133

IV. Hematologic diseases .......................................................................................... 135

59) Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) ................................................................................................. 135

60) Macrocytic and megaloblastic anaemias................................................................................. 137

61) Hemolytic anaemias. Hemolysis ............................................................................................. 139

62) Aplastic anaemia. Agranulocytosis.......................................................................................... 142

63) Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) ....................................................................................................... 144

64) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) ........................................................................................... 146

65) Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) ..................................................................................... 149

66) Myeloma multiplex/multiple myeloma (MM) (AKA plasmacytoma, plasma cell myeloma,

myelomatosis, Kahler’s disease) ................................................................................................... 150

67) Chronic myelogenous/myeloid leukaemia (CML) .................................................................... 152

68) Polycythaemia vera (PV/PCV) (AKA primary polycythaemia) ................................................. 153

69) Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).............................................................................................. 154

70) Acute lymphocytic leukaemia in adults (ALL) .......................................................................... 156

71) Haemorrhagic diathesis – features and classification. Thrombocytopenia – classification.

Autoimmune thrombocytopenia ..................................................................................................... 158

72) Haemorrhagic diathesis – classification. Haemophilia ............................................................ 161

V. Endocrine and metabolic diseases ....................................................................... 163

73) Diabetes mellitus – pathogenesis, clinical features ................................................................. 163

74) Diabetes mellitus – treatment w/insulin and oral medications ................................................. 164

75) Treatment of diabetic complications ........................................................................................ 167

76) Obesity and metabolic syndrome ............................................................................................ 169

77) Dyslipidemia ............................................................................................................................ 171

78) Hypothyroidism ....................................................................................................................... 172

79) Thyrotoxicosis. Hyperthyroidism ............................................................................................. 174

80) Nodular goiter. Endemic and sporadic goiter .......................................................................... 177

81) Hyperprolactinemia. Prolactinoma .......................................................................................... 180

82) Hypercalcaemic states ............................................................................................................ 182

83) 9 – Hypocalcaemic states ....................................................................................................... 183

84) 10 – Acromegaly and diabetes insipidus ................................................................................. 185

85) 11 – Hypercorticism (AKA Cushing’s syndrome and disease, hypercortisolism) .................... 187

86) 12 – Hypocorticism (AKA adrenal insufficiency, Addison’s disease)....................................... 189

87) Hypogonadism. Clinical features ............................................................................................. 193

88) Autoimmune disorders of the thyroid gland ............................................................................. 194

89) Polycystic ovary syndrome ...................................................................................................... 197

VI. Gastroenterology ................................................................................................. 201

90) Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) .............................................................................. 201

91) H. pylori infection ..................................................................................................................... 202

92) Peptic ulcer ............................................................................................................................. 203

93) Malabsorption .......................................................................................................................... 205

94) Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease – inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) ......................... 206

95) Tumours of the colon (colorectal cancer – CRC) .................................................................... 210

96) Chronic viral hepatitis .............................................................................................................. 213

97) Fatty liver. Alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis ........................................................... 218

98) Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC). Primary sclerosing cholangitis ............................................... 219

99) Autoimmune hepatitis .............................................................................................................. 221

100) Liver cirrhosis – etiology, pathogenesis, clinical features...................................................... 222

101) Liver cirrhosis – complications: oesophageal varices, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

(SBP), hepatorenal syndrome, portal encephalopathy .................................................................. 225

102) Ascites – diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment............................................................ 229

103) Cholelithiasis – etiology, pathogenesis, clinical features....................................................... 231

104) Cholelithiasis – complications: cholecystitis, cholangitis ....................................................... 233

105) Acute and chronic pancreatitis .............................................................................................. 236

106) Cholestasis/jaundice ............................................................................................................. 239

VII. Nephrology (Renal diseases) ............................................................................. 242

109) Membranous glomerulonephritis ........................................................................................... 246

110) IgA glomerulonephritis .......................................................................................................... 247

111) Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) .............................................................. 247

112) Lupus nephritis ...................................................................................................................... 248

114) Renal Amyloidosis ................................................................................................................. 251

115) Acute urinary tract infections (UTIs) ...................................................................................... 253

116) Chronic pyelonephritis ........................................................................................................... 255

117) Renal tuberculosis ................................................................................................................. 256

118) Nephrolithiasis ....................................................................................................................... 257

119) Adult polycystic renal disease ............................................................................................... 258

120) Acute renal failure – renal parenchyma and treatment ......................................................... 260

121) Chronic renal failure – stages and clinical course ................................................................. 264

VIII. Toxicology and Allergology ................................................................................ 268

122) Toxicodynamics and toxicokinetics of exogenous poisons ................................................... 268

123) Treatment of acute exogenous poisoning ............................................................................. 269

124) Acute exogenous poisoning w/medicines used to treat cardiovascular diseases,

benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidiabetic, antipyretic, analgesics, and antiemetic agents .... 271

125) Acute exogenous poisoning w/alcohols: ethanol, methanol, ethylene glycol ........................ 274

126) Acute exogenous poisoning w/psychoactive substances...................................................... 276

127) Acute exogenous poisoning w/organophosphate compounds .............................................. 278

128) Acute exogenous poisoning w/carbon monoxide .................................................................. 279

129) Snake venom poisoning ........................................................................................................ 280

130) Acute exogenous poisoning w/mushrooms ........................................................................... 281

131) Hereditary angioedema (HAE) .............................................................................................. 283

132) Asthma: epedimiology, pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis and differential diagnosis 284

133) Insect allergy ......................................................................................................................... 289

134) Food allergy .......................................................................................................................... 290

135) Drug allergy: type I, II, III ....................................................................................................... 291

136) Drug allergy: type IV a, b, c, d ............................................................................................... 295

137) Anaphylaxis ........................................................................................................................... 297

138) Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (AKA extrinsic allergic alveolitis) ............................................. 298

IX. Oncologic Diseases ............................................................................................. 300

139) Renal tumors ......................................................................................................................... 300

141) Esophageal cancer ............................................................................................................... 306

142) Gastric cancer ....................................................................................................................... 307

143) Tumors of the colon .............................................................................................................. 309

144) Liver tumors .......................................................................................................................... 312

145) Pancreatic cancer ................................................................................................................. 315

146) Carcinoma of the biliary duct ................................................................................................. 317

147) Tumor of the thyroid gland .................................................................................................... 318

X. Principles of Treatment ......................................................................................... 323

148) Treatment of peptic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract ..................................................... 323

149) Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection ............................................................................. 324

150) Principles in treatment of chronic liver disease ..................................................................... 326

151) Treatment of chronic viral hepatitis ....................................................................................... 328

152) Treatment of the liver cirrhosis complications: esophageal varices, ascites, spontaneous

bacterial peritonitis, hepato-renal syndrome, encephalopathy ...................................................... 330

153) Treatment of chronic cholestasis........................................................................................... 334

154) Antibacterial treatment of the biliary tract infection................................................................ 335

155) Treatment principles in poisoning.......................................................................................... 336

156) Treatment of urinary tract infection........................................................................................ 338

157) Treatment in glomerulonephritis ............................................................................................ 340

158) Diabetes mellitus - treatment with insulin and oral medications ............................................ 344

159) Treatment of diabetic complications. ..................................................................................... 350

160) Treatment with NSAIDs ......................................................................................................... 352

161) Treatment in predialysis period of chronic renal failure and indications for dialysis .............. 354

162) Clinical and pharmacological approach in NSAIDs therapy. ................................................. 357

163) Treatment of bacterial infection ............................................................................................. 357

164) Treatment with diuretics ........................................................................................................ 362

165) Treatment with steroids ......................................................................................................... 367

166) Treatment with immunomodulators ....................................................................................... 370

167) Treatment with cytostatics ..................................................................................................... 373

168) Treatment of the thromboembolism ...................................................................................... 376

169) Treatment of pneumonia ....................................................................................................... 379

170) Treatment of asthma. ............................................................................................................ 381

I.Pulmonology

1) Acute bronchitis, tracheobronchitis, bronchiolitis

Acute bronchitis (AKA chest cold)

Definition = short-term (acute) inflammation of the bronchi

Etiology = virus (most common – >90% - influenza A and B, parainfluenza, adenovirus, RSV,

rhinovirus, coronavirus) or bacterial infection, air pollution.

Pathophysiology

•

Damage caused by irritation of the airways → inflammation → neutrophils infiltrate the lung

tissue

•

Mucosal hypersecretion is promoted by a substance released by neutrophils

•

Further obstruction to the airways is caused by > goblet cells in the small airways (chronic

bronchitis)

Symptoms

•

Cough: dry in the beginning later w/sputum (expectorating cough). Self-limiting 2/3wks

•

Chest pain (retrosternal) during cough as a sign of tracheitis

•

Runny nose, sore throat, headache (symptoms of the preceding/ simultaneous URTI)

•

SOB (in bronchiolitis), wheezing

•

Fever, fatigue, weakness (malaise), loss of appetite, myalgias

Physical examination

•

Acute bronchitis is a clinical diagnosis

•

Coarse or ↓ vesicular breathing

•

Auscultation = wheezing, rhonchi, coarse crackles.

Lab tests

•

Blood = ↑ WBC, sedimentation rate, and CRP

•

Microbiology = sputum culture for bacterial infection, serological test for viral infection

Instrumental tests

•

Chest X-ray = ↑ lung markings. Chest X-ray used to exclude pneumonia

•

Spirometry = Restrictive type respiratory failure in bronchiolitis (↓ FVC and FEV1, FEV1/FVC

≥ 70%)

•

Blood gases = hypoxemia often w/hypercapnia in bronchiolitis

Complications = pneumonia and chronic bronchitis

Treatment = most cases are self-limiting and resolve themselves w/in a few weeks. Pain meds

(NSAIDs) help with symptoms; rest and hydration recommended. Anti-B not recommended

Tracheobronchitis

Definition = inflammation of the trachea and bronchi. It is characterised by a cough, fever, and

purulent sputum ∴ suggestive of pneumonia.

Etiology

•

Ventilator-associated = nosocomial infection usually contracted in an ICU when a mechanical

ventilator is used. The insertion a tracheal tube can cause an infection in the trachea which

then colonises and spreads to the bronchi

•

Fungal

•

Herpetic = caused by the HSV and causes small ulcers covered in exudate (containing

necrotic cells from the mucosal epithelium) to form on the mucous membranes

Bronchiolitis

Definition = blockage of the bronchioles in the lungs due to a viral infection. It usually only occurs in

children <2 years

Etiology = most commonly caused by RSV or human rhinovirus

Risk factors = preterm infant, younger age at onset of illness (<3 months), congenital heart disease,

immunodeficiency, chronic lung disease, neurological disorders, tobacco smoke exposure

Clinical findings = initially fever, rhinorrhoea, cough; respiratory distress as a result of bronchiole

obstruction presents w/tachypnoea, prolonged expiration, nasal flaring, cyanosis

Diagnosis

•

Clinical examination – auscultation = wheezing, crackles

•

CXR sometimes useful to exclude pneumonia, but not indicated in routine cases

DDx = asthma, bacterial pneumonia, congenital heart disease, whooping cough, CF, allergic rxn, FB

aspiration

Treatment

•

Infection will run its course and complications are typically from symptoms themselves.

•

Maintaining hydration and diet is important in management

•

Children w/severe symptoms may be considered for hospital admission – indications include =

toxic appearance, poor feeding, pO2 <92%, pre-existing heart/lung/neurological conditions,

immunodeficiency

2) Chronic bronchitis, pulmonary emphysema, COPD

Chronic bronchitis

Definition = productive cough that lasts for at least 3 months/> per year for 2 consecutive years.

When this occurs together w/↓ airflow it is known as COPD.

Pathophysiology

•

Smoking → exposure to irritants and chemicals → hypertrophy and hyperplasia of bronchial

mucinous glands (main bronchi) and goblet cells (bronchioles) → ↑ mucous production →

airway obstruction

•

Smoking = cilia are < mobile = hard to move mucous

•

Mucous hypersecretion + poor cilia function = productive cough

Excess mucus can narrow the airways, thereby limiting airflow and accelerating the decline in lung

function, and result in COPD. Excess mucus shows itself as a chronic productive cough and its

severity and volume of sputum can fluctuate in periods of acute exacerbations.

Predisposition factors = frequent respiratory infections, smoking, polluted environment

Symptoms = occasionally, slight morning cough; during exacerbation same as acute bronchitis

Physical examination, lab tests, and instrumental tests in cases w/exacerbation same as in acute

bronchitis

Complications

•

Bronchiectasis

•

Pulmonary emphysema (COPD)

•

Pneumofibrosis

•

Possible predisposition factor for neoplasm

Pulmonary emphysema

Definition = permanent dilation of pulmonary air spaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, caused by

destruction of the alveolar walls and pulmonary capillaries required for gas exchange.

Etiology

•

Smoking (incites lung injury)

•

Inherited (congenital) α1-antitrypsin (enz. protecting the lung from protease enz. such as

neutrophil elastase) deficiency

•

Pulmonary emphysema is a complication of chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, and bronchial

asthma

Pathophysiology

•

Emphysema is due to breakdown of elastin and other

alveolar wall components by proteases. Normally antiprotease enz. (e.g. α1-antitrypsin) protect the lung. In

emphysema:

•

Cigarette smoke/other irritants → attraction of

inflammatory cells → release of elastase (usually

inhibited by α1-antitrypsin) – in smokers anti-protease

production and release may be inadequate to

neutralise the excess protease production →

destruction of elastic fibers in lung → emphysema

Classification

•

Centrilobular emphysema (centroacinar emphysema) = most common type; classically seen

in smokers; characterised by destruction of the respiratory bronchiole (central portion of the

acinus); spares distal alveoli; affects upper lobes

•

Panlobular emphysema (panacinar emphysema) = rare; associated w/ α1-antitrypsin

deficiency; characterised by destruction of the entire acinus (respiratory bronchiole and

alveoli); affects lower lobes

•

Cicatricial emphysema = caused by exposure to quartz dust; characterised by chronic

inflammation and nodular scar formation

•

Giant bullous emphysema = characterised by large bullae that extrude into surrounding tissue;

bullae may rupture → pneumothorax

•

Senile emphysema = loss of pulmonary elasticity w/age; non-pathological – normal

consequence of aging

Symptoms

•

SOB, initially during exercise, later at rest, but it is not relieved significantly in sitting position

•

Cough w/sputum

•

Easy tiredness, fatigue

Physical examination

•

In patient w/respiratory failure = general cyanosis and polycythaemia

•

Short neck, sometimes high neck vv.

•

Barrel chest = occurs because the lungs are chronically overinflated w/air, so the rib cage

stays partially expanded all the time

•

↓ vocal fremitus, box-like percussion sound, lower position of lung bases, ↓respiratory

mobility, ↓ vesicular breathing w/prolonged exhale, often whistling and snoring wheezes.

Lab tests

•

Blood = ↑ Hb, RBC, HTC; ↓ sedimentation rate in patients w/respiratory failure and

polycythemia

•

Tests for infection are often required

Instrumental tests

•

Chest X-ray = > air in the lungs, dilated intercostal spaces, often ↑ lung markings for

concomitant chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis

•

Spirometry = obstructive type respiratory failure (FEV1/FVC < 70%)

•

Blood gases = hypoxemia and hypercapnia, ↓ O2 saturation

Complications = R side HF, pneumothorax (very rare)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD)

Definition = a type of obstructive lung disease characterised by chronic breathing problems and poor

airflow.

The term COPD encompasses 2 types of obstructive airway disease: emphysema, w/enlargement of

airspaces and destruction of lung tissue, and chronic (obstructive) bronchitis, w/↑ mucous production,

obstruction of small airways, and a chronic productive cough. People w/COPD often have

overlapping features of both disorders

Etiology = tobacco smoking, air pollution, occupational exposure, genetics

Classification (Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease – GOLD)

•

GOLD classifies COPD according to the severity of airflow limitation (GOLD 1-4) and the

ABCD assessment tool, which takes into account the modified British medical Research

Council dyspnoea scale, COPD assessment tool (CAT), and risk of exacerbation

•

COPD was previously classified into chronic bronchitis and emphysema. This is now

considered outdated as most COPD patient have a combo of both

Category

Symptoms

Exacerbations per year

FEV1% predicted

GOLD 1 (Class I)

Mild

≤ 1 (w/no hospital admission)

≥ 80%

GOLD 2 (Class II)

Moderate

≤ 1 (w/no hospital admission)

50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%

GOLD 3 (Class III)

Severe

GOLD 4 (Class IV)

•

≥2

•

≥ 1 leading to hospital

admission

30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%

Very severe

< 30%

Clinical findings

•

Symptoms are minimal or non-specific until the disease reaches an advanced stage

•

Presenting findings = chronic productive cough, SOB, tachypnoea, pursed lip breathing (>

common in emphysema), prolonged exhalation (> work needed to exhale), wheezing, crackles

cyanosis due to hypoxemia, tachycardia

•

Barrel chest is characteristic sign of COPD (> common in emphysema)

•

Advanced COPD = pulmonary HT → R sided heart failure (cor pulmonale) – symptoms

include peripheral oedema and bulging neck vv. (sign of ↑ jugular venous pressure)

•

Asynchronous movement of the chest and abdomen during respiration

•

Use of accessory respiratory muscles due to diaphragmatic dysfunction

•

Hyperresonant lungs; ↓ diaphragmatic excursion, and relative cardiac dullness on percussion;

↓ breath sounds on auscultation (“silent lung”)

•

Nail clubbing in the case of certain comorbidities (e.g. bronchiectasis, pulmonary fibrosis, lung

cancer)

•

“Pink puffer” – for people w/predominant emphysema = lack of cyanosis, the use of accessory

muscles, and pursed-lip (“puffer”) breathing

•

“Blue bloaters” – for people w/predominant chronic bronchitis = cyanosis (due to hypercapnia)

and fluid retention associated w/R sided heart failure

Pink puffer

Main pathomechanism

Clinical features

Emphysema

Blue bloater

Chronic bronchitis

•

Non-cyanotic

•

Productive cough

•

Cachectic (physical wasting)

•

Overweight

•

Pursed lip breathing

•

Peripheral oedema

•

Mild cough

PaO2

Slightly ↓

Markedly ↓

PaCO2

Normal (possibly in late hypercapnia)

↑ (early hypercapnia)

Diagnosis

•

Considered in anyone >35-40 who has SOB, chronic cough, sputum production, or frequent

winter colds and a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease

•

Pulmonary function test (spirometry – gold standard, confirms the diagnosis) = FEV1/FVC <

70%; ↓ FEV1 (<80%) (MNEMONIC = COP w/low FEVer)

•

ABG = many patients w/severe COPD have chronic hypercapnia due to CO2 trapping from

hyperinflation and progressive loss of pulmonary elasticity

•

CBC = ↑ serum hematocrit (chronic hypoxemia → ↑ release of EPO → ↑ erythropoiesis → ↑

secondary polycythemia (↑ in total RBC mass))

•

CXR = hyperinflated lungs (barrel chest), flattened diaphragm, ↑ retrosternal space, and

bullae

•

High-resolution CT of the chest may show the distribution of emphysema throughout the lungs

DDx

•

Other causes for SOB = congestive HF, PE, pneumonia, pneumothorax

•

Asthma = distinction is made on the basis of the symptoms, smoking history, and whether

airflow limitation is reversible w/bronchodilators at spirometry (post-bronchodilator test –

spirometry to establish baseline, inhalation of salbutamol, repeat spirometry again after 10-15

mins)

Delta FEV1 <12% (irreversible bronchoconstriction) = COPD is > likely

Delta FEV1 >12% (reversible bronchoconstriction) = asthma is > likely

Management

•

Stopping smoking, pulmonary rehabilitation (program of exercise, disease management, and

counselling, coordinated to benefit the individual), non-invasive ventilation, O2 therapy (PO2

<50-55 mmHg or O2 saturation <88%)

•

Vaccinations = pneumococcal (↓ incidence community-acquired pneumonia and invasive

pneumococcal disease), influenza (↓ incidence of lower RT infections and death)

1st line treatment of COPD consists of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and

phosphodiesterase (PDE) type 4 inhibitors:

•

Bronchodilators:

Short-acting beta agonists (SABAs) = e.g. salbutamol,

fenoterol

Long-acting beta agonists (LABAs) = e.g. salmeterol,

formoterol

Short-acting muscarinic antagonists (SAMAs) = e.g.

Ipratropium bromide

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) = e.g. Tiotropium bromide

•

ICS = e.g. Budesonide, fluticasone, Beclomethasone

•

PDE type 4 inhibitors = e.g. roflumilast

•

Theophylline can be used for severe and refractory COPD; long-term O2 therapy can be used

in case of PaO2 ≤ 55 mmHg or SaO2 ≤ 88% at rest

3) Respiratory failure – pathophysiology and clinical features

Definition = failure of the respiratory system to maintain gas exchange → hypoxia or hypercapnia

Classification and Etiology

Type 1 (hypoxemic)

•

Defined as hypoxemia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg) w/normo- or hypocapnia (PaCO2 ≤ 50 mmHg)

•

It is due to failure of the gas exchange function of the lung – failure of the lungs and heart to

provide adequate O2 to meet metabolic needs

This type of respiratory failure is caused by conditions that affect oxygenation such as:

•

Low ambient O2 (e.g. at high altitudes)

•

Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatch – most common = ↓ ventilation to normally perfused

regions or ↓ perfusion to normally ventilated regions (e.g. pulmonary embolism)

•

Alveolar hypoventilation = ↓ minute volume due to ↓ respiratory muscle activity (e.g. in acute

neuromuscular disease); this form can also cause type 2 respiratory failure if severe

•

Diffusion impairment = impaired gas exchange due to ↑ in distance for diffusion or a ↓ in the

permeability/SA of the respiratory membranes. Most commonly occurs in parenchymal

diseases such as pneumonia, pulmonary oedema, and ARDS

•

Shunt = pathologic condition in which alveoli are perfused but not ventilated – oxygenated

blood mixes w/non-oxygenated blood from the venous system (e.g. R→L shunt)

Type 2 (hypercapnic)

•

Defined as hypoxemia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg) w/hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 50 mmHg)

•

It is due to ventilatory failure – people are unable to maintain a level of alveolar ventilation

sufficient to eliminate CO2 and keep arterial O2 levels w/in normal range. Underlying

mechanism is hypoventilation

The underlying causes include:

•

↑ airway resistance (e.g. COPD, asthma, suffocation)

•

↓ breathing effort (e.g. drug effects, brain stem lesion, extreme obesity)

•

↓ in the area of the lung available for gas exchange (e.g. chronic bronchitis)

•

Neuromuscular problems (e.g. Guillain-Barre syndrome, motor neuron disease)

•

Deformed (kyphoscoliosis), rigid (ankylosing spondylitis), or flail chest

Type 3 (peri-operative)

•

Generally a subset of type 1 failure but is sometimes considered separately because it is so

common

•

Residual anaesthesia effects, post-operative pain, and abnormal abdominal mechanics

contribute to ↓ FRC and progressive collapse of dependant lung units

•

Causes of post-operative atelectasis include = ↓ FRC, supine/obese/ascites, anaesthesia,

upper abdominal incision, airway secretions

Type 4 (shock)

•

Describes patients who are intubated and ventilated in the process of resuscitation for shock

•

Cardiogenic, hypovolemic, septic

Clinical manifestations

Signs and symptoms of type I RF

(hypoxemia)

Signs and symptoms of type II RF

(hypercapnia)

Dyspnoea, irritability

Headache

Confusion, somnolence, fits

Behavioural change

Tachycardia, arrhythmia

Coma

Tachypnoea

Papilloedema

Cyanosis

Warm extremities

There are signs that suggest a possible underlying cause of RF including:

•

Hypotension usually w/signs of poor perfusion suggest severe sepsis or pulmonary embolism

•

HT usually w/signs of poor perfusion suggests cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

•

Wheeze and stridor suggest airway obstruction

•

Tachycardia and arrhythmias may be the cause of cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

•

Elevated jugular venous pressure suggests R ventricular dysfunction

•

Respiratory rate < 12 beats/min in spontaneously breathing patient w/hypoxia suggest

nervous system dysfunction

•

Paradoxical respiratory motion suggest muscular dysfunction

Diagnosis

•

ABGs; renal and liver function tests (may indicate etiology); CBC

•

Pulmonary function test = identifies obstruction, restriction, and gas diffusion abnormalities.

Normal FEV1 and FVC suggest disturbance in respiratory control; ↓ FEV1/FVC indicates

airflow obstruction; ↓ FEV1 and FVC and maintenance of FEV1/FVC suggests restrictive lung

disease

•

Capnography = provides a continuous reading of respiratory function and end tidal CO2

•

Pulse oximetry = gives a continuous measure of blood oxygen saturation

•

ECG = to monitor cardiac function

Treatment

•

Treatment of the underlying cause, if possible. This may involve medication such as

bronchodilators, anti-B, glucocorticoids, diuretics, amongst others. Respiratory

therapy/physiotherapy may be beneficial in some causes of RF

•

Type 1= O2 therapy to achieve adequate O2 saturations. Lack of response to O2 may be an

indication for other modalities such as heated humidified high-flow therapy, continuous

positive airway pressure (CPAP) or (if severe) endotracheal intubation and mechanical

ventilation

•

Type 2 = non-invasive ventilation, unless medical therapy can improve the situation

4) Bacterial Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

5) Non-Bacterial Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

6) Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)

Definition = respiratory infection characterised by inflammation of the alveolar space and/or the

interstitial tissue of the lungs.

Etiology

Type of pneumonia

CAP

Common pathogens

Typical pneumonia:

•

Streptococcus pneumoniae (most common)

•

H. influenzae

•

M. catarrhalis

•

K. pneumoniae

•

S. aureus

Atypical pneumonia:

•

Bacteria = M. pneumoniae (most common); Chlamydia pneumoniae;

L. pneumophila → legionellosis; C. burnetti → Q fever

•

Viruses = RSV, influenza, CMV, adenovirus, SARS-CoV-2

•

HAP

G(-) pathogens = P. aeruginosa; enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter

species

•

S. aureus

•

S. pneumoniae

Lobar pneumonia

S. pneumoniae is most common cause

Bronchopneumonia

S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae

Interstitial pneumonia

M. pneumoniae, C. pneumonia, Legionella, viruses (RSV, CMV, influenza)

Pneumonia in

immunocompromised patients

Bacteria

•

Encapsulated bacteria (S.Pneumoniae, H.influenzae)

•

S. aureus

• G -ve bacteria

Fungal

•

Pneumocystis jirovecii

•

Aspergillus fumigatus

•

Histoplasma capsulatum

•

Candida species

•

Coccidioides immitis

Viral

•

CMV

Risk factors

•

Old age and immobility of any cause

•

Chronic diseases = pre-existing cardiopulmonary conditions (asthma, COPD, HF),

acquired/congenital abnormalities of the airways

•

Immunosuppression = HIV, DM, alcoholism, malnutrition

•

Impaired airway protection = altered consciousness (stroke, seizure, anaesthesia,

drugs/alcohol), dysphagia, smoking,

•

Environmental factors = crowded living conditions, toxins

Classification

Etiology

•

Primary pneumonia = no apparent pre-existing conditions that may predispose to pneumonia

•

Secondary pneumonia = pre-existing conditions that predispose to pneumonia – asthma,

COPD, HF, CF, viral URT infections, anatomical abnormalities, bronchial tumours

Location acquired

•

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) = pneumonia acquired outside of a healthcare

establishment

•

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) = nosocomial pneumonia, w/onset >48 hours after

admission. Ventilator-associated pneumonia is a subtype

•

Healthcare-associated pneumonia = pneumonia that is acquired in healthcare facilities

Clinical features

•

Typical pneumonia = pneumonia featuring classic symptoms (typical findings on auscultation

and percussion); manifests as lobar or bronchopneumonia

•

Atypical pneumonia = pneumonia w/< distinct classical symptoms and often unremarkable

findings on auscultation and percussion; manifests as interstitial pneumonia

Area of the lung affected

•

Lobar pneumonia = pneumonia affecting one lobe of a lung. Multilobar pneumonia refers to

involvement of multiple lobes; panlobar pneumonia involves all the lobes of a single lung

•

Bronchopneumonia = pneumonia affecting the tissue around the bronchi and/or bronchioles

•

Interstitial pneumonia = pneumonia affecting the tissue between the alveoli

•

Cryptogenic organising pneumonia = non-infectious pneumonia of unknown etiology

characterised by involvement of the bronchioles, alveoli, and surrounding tissue

Pathophysiology

Most commonly spread by microaspiration (droplet infection) of airborne pathogens or oropharyngeal

secretions

1) Failure of protective pulmonary mechanisms – e.g. cough reflex, mucociliary clearance,

alveolar macs

2) Infiltration of pulmonary parenchyma by the pathogen → interstitial and alveolar inflammation

3) Impaired alveolar ventilation → V/Q mismatch w/intrapulmonary shunting

4) Hypoxia due to ↑ alveolar-arterial O2 gradient

Pattern of involvement

Lobar pneumonia

•

Classic (typical) pneumonia of an entire lobe; primarily caused by pneumococci

•

Characterised by inflammatory intra-alveolar exudate, resulting in consolidation

•

Can involve the entire lobe or the whole lung

•

Stages = congestion (day 1-2), red hepatisation (day 3-4), grey hepatisation (day 5-7), and

resolution (day 8 to week 4). In stage 1 and 2 the alveolar lumen are only partially filled,

whereas in stage 2 and 3 they are filled w/exudate rich in RBC and WBC respectively

Bronchopneumonia

•

Most commonly a descending infection that is characterised by acute inflammatory infiltrates

that fill the bronchioles and adjacent alveoli (patchy distribution)

•

Usually involves the lower lobes or R middle lobe and affects ≥1 lobe

•

Manifests as typical pneumonia

Interstitial pneumonia

•

Characterised by a diffuse patchy inflammation that mainly involves the alveolar interstitial

cells

•

Bilateral multifocal opacities are classically found on CXR

•

Manifests as atypical pneumonia

•

Often has an indolent course (walking pneumonia)

Clinical manifestations

Typical pneumonia

Characterised by sudden onset of symptoms caused by lobar infiltration

•

Severe malaise

•

High fever and chills

•

Productive cough w/purulent sputum (yellow-green)

•

Tachypnoea and dyspnoea (nasal flaring, thoracic retractions)

•

Pleuritic chest pain when breathing, often

accompanying pleural effusion

•

Pain that radiates to the abdomen and epigastric

region (particularly in children

•

On examination = crackles and bronchial breathing on

auscultation; enhanced bronchophony, egophony, and

tactile fremitus; dullness on percussion (indicated

consolidation in cases of localised pneumonia)

Atypical pneumonia

Typically has an indolent course (slow onset) and commonly

manifests w/extrapulmonary symptoms

•

Dry cough

•

Dyspnoea

•

Auscultation often unremarkable

•

Common extrapulmonary features = fatigue, headaches, sore throat, myalgias, malaise

Diagnosis

•

Labs = CBC and inflammatory markers (↑ CRP and ESR, leukocytosis); ↑ serum procalcitonin

(an acute phase reactant that can help diagnose bacterial LRT infections); ABG = ↓ PaO2,

BMP, LFT’s

•

Microbiological blood + sputum culture, Ag test (pneumococcal urinary), PCR

(chlamydophilia), NAAT (Influenza, RSV)

•

CXR = opacity of ≥1 lobes (lobar); air bronchograms (appearance of translucent bronchi

inside opaque areas of alveolar consolidation); poorly defined patchy infiltrates scattered

throughout the lungs (bronchopneumonia); diffuse reticular opacity and absence of

consolidation (interstitial)

•

CT w/out contrast = localised areas of consolidation, air bronchograms, ground-glass

opacities, pleural effusion/empyema, nodules

•

Bronchoscopy = indicated in inconclusive CT and need for pathohistological diagnosis

•

Diagnostic thoracentesis

7) Treatment of pneumonia

Criteria for hospitalisation

Every patient should be assessed individually and clinical judgement is the most important factor. The

pneumonia severity index (PSI) and the CURB-65 score are tools that can help to determine whether

to admit a patient.

CURB-65 score

•

Confusion (disorientation, impaired consciousness)

•

Serum Urea > 7 mmol/L

•

Respiratory rate ≥30/min

•

BP = systolic ≤90 mmHg or diastolic ≤60 mmHg

•

Age ≥ 65 years

•

Each finding is assigned 1 point

•

Score 0 or 1 = patient may be treated as outpatient

•

Score ≥2 = hospitalisation is indicated

•

Score ≥ 3 = consider ICU level of care

•

If serum urea level is not known or unavailable, a score of ≥1 requires hospitalisation

Supportive therapy

•

Sufficient rest (not absolute bed rest) and physical therapy

•

Hydration with PO fluids or IV fluids (see IV fluids)

•

Treat hypoxemia.

•

Supplemental oxygen as needed for hypoxia, mechanical ventilation

•

Incentive spirometer

•

Antipyretics, analgesics as needed (e.g., acetaminophen)

•

Expectorants and mucolytics (N-acetyl cysteine)

•

Antitussives (e.g., codeine)

Empiric anti-B therapy for CAP in an outpatient setting

Patient profile

Recommended empiric anti-B regimen

Previously healthy

patient w/out

comorbidities or risk

factors for resistant

pathogens

Monotherapy w/one of the following:

Patients w/comorbidities

or risk factors for

resistant pathogens

Combo therapy

•

Amoxicillin (500 mg 3X/day)

•

Doxycycline (200 mg on 1st day, then 100 mg 1X/day orally)

•

Macrolide – azithromycin or clarithromycin (500 mg 2X/day)

•

In pregnancy = erythromycin (500 mg 4X/day)

•

An anti-pneumococcal β-lactam (amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime,

cefpodoxime) PLUS azithro-/clarithromycin or doxycycline

Monotherapy w/a respiratory fluoroquinolone:

•

Gemifloxacin (320 mg 1X/day)

•

Moxifloxacin (400 mg 1X/day)

•

Levofloxacin (500 mg 2X/day)

•

5 days of therapy is usually sufficient for CAP that is treated in the outpatient setting

•

Any patient being treated in a primary care setting should be re-examined after 48-72 hours to

evaluate the efficacy of the prescribed anti-B

Empiric anti-B therapy for CAP in an inpatient setting

Patient profile

Non-severe CAP/non-ICU

treatment

Recommended empiric anti-B regimen

Combo therapy

•

An anti-pneumococcal β-lactam (amoxicillin-sulbactam,

ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) PLUS azithro-/clarithromycin or

doxycycline

Monotherapy w/a respiratory fluoroquinolone:

•

Gemifloxacin (320 mg IV 1X/day)

•

Moxifloxacin (400 mg IV 1X/day)

•

Levofloxacin (500 mg IV 2X/day)

Severe CAP/ICU treatment

Combo therapy

•

An anti-pneumococcal β-lactam (amoxicillin-sulbactam,

ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) PLUS azithro-/clarithromycin or

doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone

Alternatives for patients w/a penicillin allergy:

Risk factors for MRSA

•

Aztreonam

•

PLUS a respiratory fluoroquinolone (moxi-/levofloxacin)

Add vancomycin (15-20 mg/kg IV every 8-12 hours) or linezolid (600

mg IV/oral every 12 hours, 10-14 days)

•

5-7 days is usually sufficient

•

Consider longer courses in: patients not responding to treatment; suspected or concern for

MRSA or P. aeruginosa infection; concurrent meningitis; unusual pathogens

•

If aztreonam is used instead of β-lactam anti-B (e.g. for penicillin allergy), the addition of

MSSA (methicillin susceptible S. aureus) (e.g. a fluoroquinolone) is necessary

•

Anaerobic coverage is not routinely recommended for suspected aspiration pneumonia

(unless lung abscess or empyema is suspected)

•

Corticosteroids are not routinely recommended as adjunct therapy

Empiric anti-B therapy for hospital-acquired pneumonia

Patient profile

Patients not at high risk for

mortality and w/out risk

factors for MRSA infection

Recommended empiric anti-B regimen

Monotherapy:

•

meropenem, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam

•

Patients not at high risk for

mortality but w/risk factors for

MRSA infection

An anti-pneumococcal, anti-pseudomonal β-lactam = imipenem,

OR levofloxacin

Combo therapy:

•

One of the following anti-B w/MRSA activity = Vancomycin or

Linezolid

PLUS one of the following:

•

Anti-pneumococcal, anti-pseudomonal β-lactam = Piperacillintazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, meropenem, imipenem

Patients at high risk for

mortality and patients

w/structural lung diseases

•

A fluoroquinolone = levo-/ciprofloxacin

•

Aztreonam

Combo therapy:

•

One of the following anti-B w/MRSA activity = Vancomycin or

Linezolid

PLUS any two of the following (avoid combining 2 β-lactams):

•

Anti-pneumococcal, anti-pseudomonal β-lactam = Piperacillintazobactam, cefepime, ceftazidime, meropenem, imipenem

•

A fluoroquinolone = levo-/ciprofloxacin

•

An aminoglycoside = Amikacin, Gentamicin, tobramycin

•

Aztreonam

•

Empiric anti-B therapy should be narrowed and/or de-escalated as soon as feasible

•

7 days of therapy are usually sufficient

•

Resistance patterns can vary widely; local antibiograms should be considered when starting

empiric treatment

8) Purulent diseases – bronchiectasis, pulmonary abscess

Bronchiectasis

Definition = an irreversible and abnormal dilation in the bronchial tree, leading to build-up of mucous

that can make the lungs > vulnerable to infection

Etiology

•

Pulmonary infections (i.e. bacterial, viral, fungal)

•

Disorders of secretion clearance or mucous plugging = CF, primary ciliary dyskinesia,

smoking

•

Bronchial narrowing or other forms of obstruction = COPD, aspiration, tumours, other

congenital and acquired conditions (congenital bronchiectasis, tracheomalacia)

•

Immunodeficiency

•

Chronic autoimmune inflammatory diseases = RA, Sjogren’s syndrome

Pathophysiology

•

Development requires 2 factors: an infectious insult and impaired drainage, obstruction, or a

defect in host defence

•

This triggers a host immune response from neutrophils (elastases), ROS, and inflammatory

cytokines that result in progressive destruction of normal lung tissue

•

“Vicious cycle” theory = predisposed individual develops an excessive inflammatory response

to pulmonary infection or tissue injury. The inflammation that results is partially responsible for

the structural damage to the airways. Structural abnormalities then allow for the stasis of

mucous, which favour continued chronic infection and the persistence of the vicious cycle.

Symptoms

•

Chronic productive cough (lasting months to years), w/copious mucopurulent sputum. The

sputum is in 3 levels – upper foam-like, middle (mucous) and lower (purulent).

•

Dyspnoea

•

Occasionally haemoptysis (blood in sputum)

•

Bad breath (halitosis, oral malodour)

•

Rhinosinusitis

•

Non-specific symptoms = fatigue, weight loss, pallor due to anaemia

•

During exacerbation the same as in acute bronchitis, but more severe, similar to pneumonia

Physical examination

Mainly in auscultation – crackles and rhonchi; wheezing (due to obstruction from secretions, airway

collapsibility, or a concomitant condition); bronchophony; occasionally clubbing of the fingers

Lab tests

•

Blood = ↑ WBC, neutrophils, sedimentation rate, and CRP in cases w/inflammation. May show

anaemia of chronic disease

•

Microbiology = sputum culture

Instrumental tests

• CXR (best initial test) = inflammation and fibrosis of bronchial walls → “tram track” lines; thinwalled cysts, possible w/air-fluid levels; late stage disease = honeycombing

• High-resolution CT (confirmatory test) = dilated bronchi w/thickened walls; possible signet-ring

appearance and tram track lines; cysts and honeycombing

• Sputum culture and smear = to determine infectious etiology

• Spirometry = findings consistent w/obstructive pulmonary disease (↓ FEV1/FVC)

• Bronchoscopy = to visualise tumours, FBs, or other lesions

• Blood gases = hypoxemia, sometimes w/hypercapnia

Management

• Acute exacerbation

o

o

o

Mucolytics

Outpatient anti-B: Fluoroquinolones (Lexofloxacin)

Inpatient anti-B: MRSA (vancomycin, linezolid)

• Supportive measures

o Education, lifestyle changes, chest physiotherapy (airway clearance techniques)

o Vaccinations (influenza, pneumococcal)

o Long-term o2 therapy for chronic respiratory failure

o

Follow up every 6-12 months, spirometry every 12 months

• Treatment

o Mucoactive agents: Inhaled (hypertonic saline/ mannitol)/ Oral (N-acetly cysteine)

w/airway clearance techniques, such as high-frequency chest wall oscillation

o Bronchodilators (SABA, LABA, LAMA) in severe dyspnoea

o Corticosteroids – inhaled (asthma, CODD), systemic (ABPA)

o Long term anti-B therapy (≥ 3 exacerbations in 1 year)

w/out P. aeruginosa: Azithromycin

w/ P. aeruginosa: Tobramycin/ Aztreonam. Eradication (Oral Ciprofloxacin)

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: Macrolide + Rifampin + Ethambutol

MRSA: eradication therapy

• Anti-inflammatories = macrolides and corticosteroids

• Invasive

o Surgical resection of bronchiectatic lung/ lobectomy: indicated in p. hemorrhage

o Pulmonary artery emobolization

o Lung transplantation

Complications

•

Local = pneumofibrosis, pulmonary emphysema

•

General = amyloidosis, respiratory failure

Pulmonary abscess

Definition = a localised collection of pus and necrotic tissue w/in lung parenchyma primarily caused

by aspiration, and secondarily by tumors, microbial infection, immunocompromised, septic emboli etc.

Risk factors =

•

Risk factors for aspiration, such as:

o

o

Impaired consciousness

Impaired swallow in neurological disorders and vocal cord paralysis

•

Increased oropharyngeal bacterial growth (e.g., periodontal disease, dental abscesses,

tonsillitis)

•

Bronchial obstruction (e.g., lung cancer, foreign body aspiration, bronchial stenosis)

•

Immunocompromised state

•

Pneumonia, bronchiectasis

•

Impaired respiratory mucus clearance (e.g., cystic fibrosis)

Causative pathogens

•

Most commonly = mixed infections caused by anaerobic bacteria that colonise the oral cavity

(e.g. Peptostreptococcus spp., Prevotella spp., Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp.)

•

Less commonly = monomicrobial lung abscess caused by S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, or S.

pyogenes

•

Others

o

o

Parasitic (Entamoeba histolyitca)

Fungal (Aspergillus spp, Histoplasma spp)

Clinical manifestations = indolent presentation w/symptoms that evolve over weeks to months

(>6wks) or may be acute (< 4-6wks)

•

Fever

•

Cough w/production of foul-smelling purulent sputum

•

Anorexia, weight loss, fatigue

•

Night sweats

•

Hemoptysis

•

Pleuritic chest pain

Physical Exam

o Digital clubbing

o Dullness to percussion

o Amphoric breath sounds over abscess (harsh, hollow, high-pitched breath sounds)

Diagnosis

•

CXR/CT w/ IV contrast = irregular rounded cavity w/an air-fluid level that is dependent on

body position

o Location of abscess

Due to aspiration: typically unilateral

•

Right M lobe (typically caused by aspiration in the prone or upright

position)

•

Posterior segments of the U lobes or the superior segments of the L

lobes (typically caused by aspiration in the recumbent position).

Due to hematogenous dissemination: typically bilateral and multiple

•

CBC: ↑ WBC, maybe anemia of chronic disease

•

Gram stain, culture, and sensitivity of expectorated sputum/ pleural fluid (takes time, which is

why empirical treatment is usually initiated 1st)

•

Additional testing: HIV screening, bronchoscopy for FB, tumor, echocardiography for septic

endocarditis, clinical swallow assessment for dysphagia

Treatment

•

Admit and start immediate empiric ant-B therapy after cultures for 3-6wks

•

Anti-B treatment: Broad spectrum which covers anaerobes (e.g. ampicillin-sulbactam,

carbapenems, or clindamycin). Anti-B against Gram +ve cocci in IV drug use

o No risk of MRSA: Ampicillin-sulbactam (3g/day), Ceftriaxone+Metronidazole, Clindamy

o

•

Risk of MRSA: Vancomycin, Linezolid (600mg IV x2/day)

Interventional therapy for large abscess, significant hemoptysis, or if meds fail

o Bronchoscopic drainage/ percutaneous catheter drainage

o Surgical resection (segmentectomy or lobectomy) may be considered

Complications

•

Extension or rupture into the pleural cavity, causing:

o Pleural empyema

o Pleural effusion

o Bronchopulmonary fistula

o Pneumothorax

•

Recurrence of abscess

9) Pleural effusions

Definition = an excessive amount of fluid between the pleural layers that impairs the expansion of the

lungs OR an accumulation of fluid in the pleural cavity between the visceral and parietal pleurae

Etiology, pathophysiology, and classification

Pleural effusions can be classified by:

•

The origin of the fluid = serous fluid (hydrothorax), blood (hemothorax), chyle (Chylothorax),

pus (pyothorax/empyema)

•

By pathophysiology = transudative or exudative pleural effusion

Transudative pleural effusion

Definition

Transudate = extravascular fluid w/low

protein content and low specific

gravity.

Pathophysiology

Causes

•

↑ capillary hydrostatic pressure

•

↓ capillary oncotic pressure

(AKA colloid osmotic pressure)

•

Congestive HF

•

Hepatic cirrhosis

•

Nephrotic syndrome

•

Protein-losing enteropathy

•

Chronic kidney disease (Na+

retention)

Exudative pleural effusion

Exudate = any fluid that filters from the

circulatory system into lesions or areas of

inflammation. It has high protein content and

high specific gravity.

•

↑ capillary permeability (e.g. due to

inflammation)

•

Infection = pneumonia, TB, pleural

empyema, parasitic illness

•

Malignancies = lung cancer, metastatic

breast cancer, lymphoma,

mesothelioma

•

PE

•

Autoimmune disease = vasculitis,

lupus, RA, sarcoidosis

•

Trauma

•

Pancreatitis

Clinical manifestations

•

Patients w/small pleural effusion (<300 ml) are often asymptomatic

•

Characteristic symptoms = dyspnoea; pleuritic chest pain (sharp retrosternal pain) (can also

have abdominal pain which is confused w/acute appendicitis); dry cough; fever; symptoms of

the underlying disease

•

Inspection and palpation = asymmetric expansion and unilateral lagging on the affected side;

↓ tactile fremitus due to fluid in pleural space

•

Auscultation = faint/absent breath sounds over area of effusion, pleural friction rub

•

Percussion = dullness over the area of effusion

Diagnosis

•

CXR = standard initial imaging for detecting effusion; lat. decubitus view – allows for detection

of fluid collections as small as 5 ml

•

US = quick bedside assessment and for thoracentesis planning

•

CT = gold standard but use is limited due to radiation and contrast exposure

•

Diagnostic thoracentesis = to definitively establish the underlying etiology

Treatment

•

Stabilise patients w/respiratory distress = provide supplemental oxygen; consider urgent

therapeutic thoracentesis for certain patients (signs of ↑ work of breathing, RF, or

hemodynamic compromise secondary to the effusion)

•

Identify and treat the underlying condition

•

Therapeutic thoracentesis = removal of fluid. Indicated for large effusion w/SOB and/or

cardiac decompensation and complicated parapneumonic effusions

•

Indwelling pleural catheter can be used for patients w/rapidly accumulating pleural effusions. It

allows recurrent fluid removal w/out repeated puncture

10) Pulmonary tuberculosis

Definition = an infectious disease caused by M.TB characterised by growth of nodules (tubercles) in

the tissues, especially the lungs

M. tuberculosis

•

Obligate aerobes that thrive in an O2 rich environment – explains their tendency to cause

disease in the upper lobe/upper parts of the lower lobe of the lung, where the ventilation and

O2 content are greatest

•

Intracellular pathogens, usually infecting the macs, which explains the T-cell type of immunity

and the ↑ n.o of lymphocytes in the infected patients.

•

Acid-fast bacteria, which is used for diagnosis w/Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast staining procedure

•

It is an airborne infection spread by droplet nuclei that are harboured in the respiratory

secretions of people w/active TB. Coughing, sneezing, and talking all create respiratory

droplets.

Predisposition factors

•

Immunosuppression (TB is considered to be the most common cause of mortality in patients

w/HIV globally)

•

Contact w/sick person

•

Malnutrition and overcrowding

•

Alcoholism, smoking, drug abuse

•

Diabetes mellitus

•

Pre-existing damage to the lungs (e.g. silicosis, COPD)

•

Treatment w/TNF-α inhibitors

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of TB in a previously unexposed immunocompetent person is centred on the

development of a cell-mediated immune response that confers resistance to the organism and

development of tissue HS to the tubercular antigens. The destructive features of the disease such as

caseating necrosis and cavitation, result from the HS immune response rather than the destructive

capabilities of the tubercle bacillus.

•

M.TB enters the lungs through respiratory droplets and reaches the alveoli

Surface adhesion of M.TB to alveolar macs → inhibition of mycobacterial growth

and/or killing → involvement of additional immune cells (T cells) and deployment of

local immune response

•

Failure of the host to deal w/the infection leads

the bacteria to multiply and destroy alveolar

macs

•

Macs produce cytokines and chemokines, and

thus involve more cells to help contain the

bacteria.

•

The cell-mediated immune response results in

the development of a grey-white,

circumscribed granulomatous lesion (Ghon

focus) that contains the tubercle bacilli, modified macs, and other immune cells (epitheloid

cells, T and B cells)

•

When the n.o of organisms is high, the HS rxn produces significant tissue necrosis, causing

the central portion of the Ghon focus to undergo soft, caseous (cheese-like) necrosis.

•

Tubercle bacilli drain along lymph channels to the tracheobronchial lymph nodes of the

affected lung, and there evoke the formation of caseous granulomas

•

The spread of the TB process from primary site can be done in several ways = neighbouring

spread, bronchogenic, lymphogenic, and haematogenous

•

The combo of primary lung lesion (Ghon focus) + lymph node granulomas (pulmonary

lymphadenopathy) = Ghon complex

•

The Ghon complex undergoes progressive fibrosis, often followed by radiologically detectable

calcification (Ranke complex), and despite seeding of other organs, no lesions develop.

•

The Ranke complex is an evolution of the Ghon complex – it results from further healing and

calcification of the lesion, making it visible on CXR

•

A Ghons complex retains viable bacteria, making them sources of long-term infection, which

may reactivate and trigger secondary TB later in life

•

The primary tuberculous complex has a classical triad = primary affect w/perifocal

inflammation, lymphangitis, and regional lymphadenitis

•

Phases of primary tuberculous complex = infiltration, destruction, and dissemination

•

When treatment has started, reversal phases occur = draw back, compaction, and

calcification

•

TB of intrathoracic lymph nodes (bronchadenitis) is a major clinical form and major source for

TB dissemination. Can have infiltrative and tumorous forms

Infiltrative = caseous necrosis in the lymph node is < pronounced while the perifocal

inflammation predominates (non-specific)

Tumorous = caseous necrosis is > pronounced and there is < expressed perifocal

inflammation. This form is a sign for a greater duration of the specific process in the

lymph nodes of the lungs

Classification

•

Primary TB (primary infection) is divided into latent TB and active primary TB

•

Latent TB = primary infection w/out any pathological findings or radiological imaging; however,

screening tests indicating previous infection w/M.TB are +ve

•

Active primary TB infection (only 1-5% of cases) = primary infection w/radiologicalpathological findings of TB

•

Secondary infection is a reactivation TB = following a latent primary TB infection; 80% begin in

the lungs; endogenous reactivation (immunodeficiency) is very common whereas exogenous

reinfection is rare

Clinical manifestations

Primary TB

•

A form of the disease that develops in previously unexposed and ∴ unsensitised people

•

It manifests in childhood and typical features are:

Marked perifocal inflammation

Involvement of the draining lymph nodes

Instability to immunity

Evident intoxication syndrome

Mainly lymph-hematogenous dissemination of TB

•

Around 95% of people w/primary TB go on to develop latent infection (no signs of active TB

and don’t feel ill) in which T cells and macs surround the organism in granulomas that limit

their spread. People w/latent TB don’t have the active disease and can’t transmit the organism

to others

•

In ~ 5% of newly infected people, the immune response is inadequate → develop progressive

primary TB w/continued destruction of lung tissue and spread to multiple sites w/in the lung

•

General symptoms = fever (subfebrile), chills,

fatigue, lack of appetite and weight loss, night

sweats, lymphadenopathy, significant nail

clubbing may occur. These symptoms

depend on the severity of the diseases and

its duration.

•

Pulmonary symptoms = dyspnoea,

productive cough (possibly hemoptysis)

lasting >3 weeks

•

Chest pain provoked by breathing and cough

in patients w/pleuritis

Miliary TB

•

A form of TB that is characterised by a wide dissemination into the body and by the tiny size

of the lesions (1-5 mm)

•

Its name comes from a distinctive pattern seen on a CXR of many tiny spots distributed

throughout the lung fields w/the appearance similar to millet seeds – thus the term “miliary” TB

•

It may also infect any n.o of organs including the lungs, liver, and spleen

•

You can get acute, subacute, or chronic miliary TB

Secondary TB

•

A form of TB occurring in adults and characterised by lesions near the apex of the upper lobe

of the lung that may cavitate or heal w/scarring.

•

It may result from reinfection w/the tubercle bacilli or from reactivation of a dormant old lesion

(endogenous infection)

•

The infiltrative-pneumonic form of primary TB dominates, w/little involvement of regional

lymph nodes. It mainly has bronchogenic pathway of dissemination

•

80% pulmonary TB; 20% extrapulmonary TB

•

The most common sites of extrapulmonary TB include the bones, pleura, lymphatic system,

and liver. TB may also affect the CNS, heart, urogenital and GI tracts and the skin.

Diagnosis

History

•

Intoxication syndrome

•

Cough for >3 weeks

•

Complaints from different organs

•

Contact w/TB patient; living conditions

•

BCG status

Physical examination

•

For pulmonary TB there is no characteristic finding

•

Observe intoxication syndrome, chronic low fever (subfebrile), cough, night sweats, ↓ appetite

and weight loss.

Lab tests

•

Blood = ↑ WBC w/lymphocytosis; slightly ↑ESR; often anemia w/iron deficiency.

•

Microbiology = smear of sputum/pleural fluid for acid fast staining procedure; culture of

sputum/pleural fluid. NAAT test. Mycobacterium culture

•

Immunology = Tuberculin skin test/Mantoux (TST/PPD) test = intradermal inoculation of 0.1

ml tuberculin on the frontal side of the forearm. Result after 72 h.

Diameter < 5 mm = -ve result = vaccinal strain has been eliminated and the patient

should be revaccinated

Diameter > 15 mm = +ve result. >10 mm is +ve result for immunocompromised and

children <4

•

One of the main disadvantages of Mantoux test is cross-sensitivity to BCG vaccine

•

An interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) blood test screens for exposure to TB by indirectly

measuring the body's immune response to Ag’s derived from these bacteria.

o The QuantiFERON-TB Gold test (QFT-TB Gold) is used to detect active and latent TB

by measuring IFNγ.