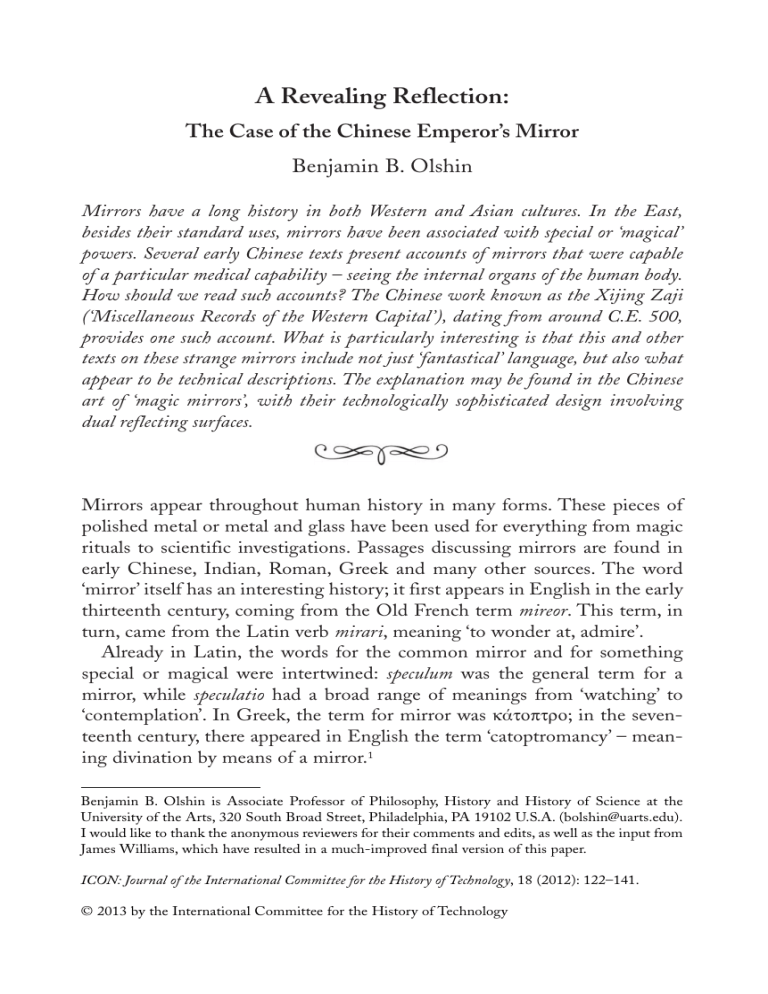

A Revealing Reflection: The Case of the Chinese Emperor’s Mirror Benjamin B. Olshin Mirrors have a long history in both Western and Asian cultures. In the East, besides their standard uses, mirrors have been associated with special or ‘magical’ powers. Several early Chinese texts present accounts of mirrors that were capable of a particular medical capability – seeing the internal organs of the human body. How should we read such accounts? The Chinese work known as the Xijing Zaji (‘Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital’), dating from around C.E. 500, provides one such account. What is particularly interesting is that this and other texts on these strange mirrors include not just ‘fantastical’ language, but also what appear to be technical descriptions. The explanation may be found in the Chinese art of ‘magic mirrors’, with their technologically sophisticated design involving dual reflecting surfaces. Mirrors appear throughout human history in many forms. These pieces of polished metal or metal and glass have been used for everything from magic rituals to scientific investigations. Passages discussing mirrors are found in early Chinese, Indian, Roman, Greek and many other sources. The word ‘mirror’ itself has an interesting history; it first appears in English in the early thirteenth century, coming from the Old French term mireor. This term, in turn, came from the Latin verb mirari, meaning ‘to wonder at, admire’. Already in Latin, the words for the common mirror and for something special or magical were intertwined: speculum was the general term for a mirror, while speculatio had a broad range of meanings from ‘watching’ to ‘contemplation’. In Greek, the term for mirror was κτοπτρο; in the seventeenth century, there appeared in English the term ‘catoptromancy’ – meaning divination by means of a mirror.1 Benjamin B. Olshin is Associate Professor of Philosophy, History and History of Science at the University of the Arts, 320 South Broad Street, Philadelphia, PA 19102 U.S.A. (bolshin@uarts.edu). I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and edits, as well as the input from James Williams, which have resulted in a much-improved final version of this paper. ICON: Journal of the International Committee for the History of Technology, 18 (2012): 122–141. © 2013 by the International Committee for the History of Technology Benjamin B. Olshin 123 Mirrors, then, are intimately connected with the idea of seeing or perceiving – but also unmasking and revealing. That revelation might be of the future or other hidden matters. Indeed, one early Chinese text speaks of a mirror with a particularly peculiar power to unmask. But before I present that text, I note an entry in a Chinese work entitled Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi (‘Anecdotes of the Kaiyuan and Tianbao Periods’) by Wang Renyu, who was active in the first part of the tenth century. The entry is entitled zhao bing jing – literally, ‘illuminating [zhao] illness [bing] mirror [jing]’: A Mirror to Illuminate Illness Ye Fashan had an iron mirror that could reflect objects in the same manner as water. Whenever a person had an illness, the mirror could be used to illuminate and see completely any obstructions in his internal organs. Then, using medicines, he would be treated until he recovered.2 A puzzling and rather ambiguous description: the mirror is described as reflecting in the same manner as water, yet we are told in the next line that mirror was able to do more than reflect – it could also reveal what was inside a person’s body.3 Certainly, the Chinese spoke of mirrors in a fantastical way – capable of ‘miraculous deeds’4 – but the passages here provide a somewhat more ‘technical’ description. Another brief mention, similar to the one above, is found in a work known as the Gujing Ji (‘Record of an Ancient Mirror’), dating from Tang dynasty (C.E. 618 - 907).5 In a story there, we read of a monk saying the following concerning a special mirror: ‘... to illuminate and see the fu and zang [organs]*, unfortunately, there was not the necessary medication. ...’ The implication is that this medication or special substance is to be used in conjunction with the mirror. As with many of these references, very little detail is provided, although it is sufficient to see that the actual use of the mirror described is quite pragmatic. What to make of such descriptions? In this paper, I will look at some accounts of these peculiar devices and suggest that they derive from a simple but subtle illusion. That illusion was produced through mirror technology developed by the Chinese centuries ago. The Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi has been described as an ‘informal’ text, ‘comprised of very short and titled anecdotes in no apparent order’; moreover, the author does not cite sources for these entries.6 What we do know is that Ye Fashan (d. C.E. 720) was a so-called ‘Daoist’ master who lived during the * This refers to the system of internal organs in traditional Chinese medicine, where certain organs are classed as yang and others as yin. The fu are yang organs, and comprise the large intestine, small intestine, stomach, gall bladder, urinary bladder, and the ‘triple-warmer’ (the openings of the stomach, small intestine, and the bladder). The zang are yin organs, and comprise the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidneys. On this classification, see Daniel P. Reid, Chinese Herbal Medicine (Boston: Shambhala, 1987), 32. 124 A Revealing Reflection Tang dynasty.7 Such masters were often said to have special powers, but here we see something more than fanciful magic: there is the explicit mention of a physical implement; i.e., the mirror, an element that makes the text seem more than a bit of whimsy. The main account of a special mirror of this kind appears in another Chinese text, the Xijing Zaji (‘Miscellaneous Records of the Western Figure 1. The text concerning the mysterious mirror, as well as other treasures. From Liu Xin and Ge Hong’s Xijing Zaji Capital’), another collec(‘Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital’). tion of anecdotes, of uncertain authorship and dating from around C.E. 500 (figure 1).8 The description here is more detailed, and begins with a discussion of other curious mechanical devices:9 When Gaozu* first entered the palace at Xianyang,† he toured the treasury storehouse, which was filled with unfathomable amounts of gold, jade, and other precious treasures. They were beyond description, and particularly surprising were five green columns seven chi five cun in height,‡ made of jade, [supporting] a lamp. Below them, there was a coiled hornless dragon§ holding a lamp in its mouth. When the lamp was lit, the scales [of the dragon] all moved and shone like stars, lighting up the whole room. * Emperor Gaozu (256 B.C.E. - 195 B.C.E.) was the first emperor of the Han Dynasty. He was one of the leaders of an insurrection in the late Qin Dynasty. Although this has been characterised as comprising ‘peasant uprisings’, one author argues that instead it was a true rebellion left by ‘men eager ... to establish new socio-political identities for themselves’. See, J.L. Dull, ‘Anti-Qin Rebels: No Peasant Leaders Here’, Modern China, 9:3 ( July 1983): 315, 285–318. † This was the royal palace of the state of Qin, at Xianyang , the capital; when Qin Shihuang unified China, it became his palace. ‡ These are traditional Chinese units of measurement; one chi equals approximately one-third of a meter, and one cun equals approximately one-thirtieth of a meter, but the precise definitions of these units has varied during the course of Chinese history. See K. Ruitenbeek, Carpentry and Building in Late Imperial China: A Study of the Fifteenth-Century Carpenter’s Manual Lu Ban Jing (Leiden, 1996), 1. § This is a typical Chinese decorative element. Benjamin B. Olshin 125 There were also twelve seated figures made of cast bronze. They were all the same height, three chi, and were seated on bamboo mats, playing the qin, zhu, sheng, etc.* All [the figures] were decorated with multi-coloured designs. They almost looked like real people. Underneath the bamboo mats, there were two bronze pipes, the top openings of which were several chi in height beyond the mats.† One of the pipes was empty, and inside the other there was a rope as thick as a finger. If one blew into the empty pipe while another person twisted the rope, all the instruments started playing, and [the effect] was no different from real music. There were also lutes, six chi in length, with thirteen strings and twentysix frets; each was completely decorated with the seven treasures‡ and an inscription that read ‘music of precious jade’. There [also] was a wind instrument of jade, two chi three cun in length, with twenty-six holes. When it was played, one would see vehicles, horses, and mountain forests, one right after another.§ When one ceased playing [the instrument], one stopped seeing these images. [This instrument] was inscribed ‘jade tube of brightness and beauty’. The text then turns to another device in the storehouse, a large mirror: There was [also] a rectangular mirror, four chi wide and five chi nine cun high. The outside and inside [of the mirror] were luminous. If one were coming directly to face the mirror, then their image would be reversed. If one touched one’s heart with the hand, and approached the mirror, then the colon, stomach, and the five zang were clearly visible [in the mirror]. If one had an internal illness, and covered their heart and faced the mirror, then the location of the illness would be known. And if a woman who had an evil heart was facing the mirror, her gall would swell and her heart would palpitate. Qin Shihuang# often used [the mirror] to check his * The qin is a Chinese instrument similar to a zither, the zhu is another type of Chinese stringed instrument, and the sheng is a kind of panpipe. † The description here is not particularly clear; Joseph Needham translates this line as follows: ‘Under the mat there two bronze tubes, the upper opening of which was several feet high and protruded beyond the end of the mat.’ See, J. Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 4 (Cambridge, 1971), 158. ‡ The ‘seven treasures’ refer to gold, silver, lapis lazuli, crystal, coral, agate, and pearl. § The meaning here is not entirely clear; the phrase ‘one would see vehicles, horses, and mountain forests’ may mean that one would see images of these when playing the jade wind instrument, but even that interpretation leaves a number of questions. Perhaps some kind of ‘magic lantern’ device is being referred to. # Emperor Qin Shihuang (259 B.C.E.–210 B.C.E.) is perhaps most famous today for the Great Wall and the terracotta warriors of his mausoleum. He was born as Ying Zheng in 259 B.C.E., and was the son of the king of the State of Qin. Ying Zheng’s ambition was to subjugate and then unify the other states such as Han, Zhao, Wei, Chu, Yan and Qi. He realised this goal by 221 B.C.E., building the first centrally-governed empire in Chinese history, and commencing what is now called the Qin Dynasty. 126 A Revealing Reflection concubines. If their galls swelled and hearts were agitated, he had them executed. Knowing this, Gaozu had [the storehouse] closed and waited for Xiang Yu,* who took it all [i.e., the contents of the storehouse] eastward. Afterwards, [its] whereabouts were unknown.10 In this text, it is interesting to see how the discussion of the mirror with special powers is part of a larger discussion of mechanical devices or automata. This makes the story seem less fantastic, although still quite peculiar. Here again, the zang comprise the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidneys. However, one modern commentator has noted that ‘the zang and fu weren’t anatomically conceived’ in early Chinese medicine but were understood in a more ‘functional’ sense.11 However, this does not mean that we should interpret the description above as not referring to actual human anatomy. The early and well-known Chinese medical work Huangdi Neijing (‘The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine’) includes ‘descriptions of the [human] body ... largely based on dissections’.12 The passage above also notes the use of the mirror by the emperor ‘to check his servants’, to see if ‘their galls swelled’. At first, this might seem rather strange; however, a Tang dynasty mirror, currently at the Cleveland Museum of Art, bears an inscription noting that it can reveal a person’s gall, and, by extension, reveal their emotions.13 In traditional Chinese medicine, the gall bladder is an organ with a key role in determining a person’s initiative and resolve.14 But what is it exactly that makes for the peculiar nature of the account? Some of the other devices described – the seated figures and the musical instruments – fit with our contemporary notion of mechanical possibilities for a pre-modern civilisation. It is the other devices in the text that defy easy historical placement or explanation; in particular, there is the strange ‘wind instrument of jade’ which allows the player to see ‘vehicles, horses, and mountain forests, one after another’ and hear ‘the hidden rumble of the vehicles’ – and, of course, the rectangular mirror which could reveal the internal organs.† A similar account, perhaps deriving from this one, is found in a ninthcentury C.E. work, the Youyang Zazu (‘Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang’) by Duan Chengshi. In this account, the mirror is also described as being large in size and able to display the five viscera.15 This text also notes * Xiang Yu (232 - 202 B.C.E.) was a famous military leader and a leader of the coalition against the Qin (Dull, ‘Anti-Qin Rebels’, 307ff ). Gaozu – at that time known as Liu Bang – was a member of this coalition, but he and Xiang Yu subsequently became enemies. In 202 B.C.E., Gaozu, as emperor, defeated Xiang Yu; for a brief summary of this conflict, see M. Bennett, The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998), 139. † It is vaguely possible that the device described there that allows one to see ‘vehicles, horses, and mountain forests, one after another’ was a kind of magic lantern or early form of zoetrope. Benjamin B. Olshin 127 that this mirror was known as the zhao gu bao; i.e., the ‘treasure [bao] that illuminates [zhao] the bones [gu]’. How should we read these texts? We could read them as pure fiction, fabrications of the author or his source; but we see that these texts, particularly the Xijing Zaji with its context of mechanical devices, have details that go beyond the framework of a simple, fanciful tale. We know that the Chinese had standard hand mirrors of polished metal, similar in design to those of the Greeks and Romans.16 Research into this field has been quite extensive, with examinations of mirrors carried out by a number of sinologists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Friedrich Hirth, who compiled an extensive study and bibliography on the subject, notes that the invention of mirrors in China was attributed to the legendary Emperor Huang Di.17 Even before the Han dynasty, there were already established terms used to refer to mirrors: jian or jing. At the beginning of this paper, I noted that in the West, terms for mirrors included broader meanings, such that speculatio, for example, had the definition of ‘contemplation’. In Chinese, jian also includes the more metaphorical meaning of ‘reflect’ and is even found in book titles such as Zizhi Tongjian, translated as ‘A Comprehensive Mirror for the Aid of Government’, a historical work written by an eleventh-century Chinese historian.18 More pragmatically, both Chinese terms for mirror include the radical jin, here meaning ‘metal’. Chinese metallurgy in the crafting of mirrors developed over a long period of time, but, with very sophisticated casting techniques already in evidence by the fourthcentury B.C.E., Chinese mirrors were made of bronze, and bronze is an alloy of copper, tin and lead; the alloy may be gold or silver in appearance, depending on the ratio of tin in the mixture (figure 2). When polished, bronze is highly reflective, and it was used in many cultures for the creation of mirrored surfaces for various purposes before the development of glass mirrors.19 In China, bronze mirrors came into Figure 2. A traditional Chinese bronze mirror. wide circulation by the time of the From A.G. Wenley, ‘A Chinese Sui Dynasty Mirror’, Artibus Asiae 25.2–3 (1962): 143, fig. 1. Warring States period (roughly from the fifth-century B.C.E. to the thirdcentury B.C.E.).20 These mirrors often had auspicious designs on the back, and sometimes had inscriptions as well.21 Hirth notes that mirrors were said 128 A Revealing Reflection by the Chinese to have a number of magical powers, including the ability to ward off of evil spirits.22 But the texts I examine here describe mirrors that are not simply for reflection – nor are they for magical or shamanistic practices. In the Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi account, we have a mirror that had the ability, the text tells us, to ‘illuminate’ the inside of a patient’s body. The language is strange to us, because we think of mirrors simply as objects that show us a reflective image, not a penetrating one. The two Chinese texts that talk about these mirrors with penetrating abilities give very specific details, and again we should ask the question: if the account is a complete fabrication, why the specificity of detail? One of the particular details is the fact that the mirror is rectangular, rather than diskshaped, the latter being much more common – Hirth notes that almost ‘all the Chinese metallic mirrors we know of are disk-shaped …’23 However, he goes on to comment: Very large mirrors, a number of feet long and broad, probably rectangular in shape, and reflecting the whole human body, are also mentioned in the post-Christian literature, some of them being imported from abroad. Several passages are on record which tell of the importation of such mirrors under the Emperor Wu-ti, who hoarded up many precious things he had sent for from western Asia; but they are mostly blended with legendary matter, which makes it difficult to treat them seriously. Such large metallic mirrors, aside from the possibility of their having been originally constructed in China itself, could easily be accounted for as importations, or imitations, of Western specimens, certainly during the first century C.E., when Seneca the Younger mentioned mirrors of sizes equal to those of human bodies.24 However, Western accounts of mirrors – which include discussions by Seneca the Younger, Pliny the Elder, Pausanias and others – do not attribute to them any penetrative powers. These sources have discussions of various kinds of ‘trick’ mirrors – for example, convex and concave mirrors – that can distort reflections, but nothing exactly as we have in our two Chinese texts here.25 It seems as if the authors of these Chinese texts are struggling to explain some kind of mechanical device, but with their language not being sufficient to the task. This does not mean that the Chinese language itself is to blame, and in fact the belief that Chinese is somehow inherently unable to communicate scientific and technological concepts has been roundly refuted.26 However, the authors of the Chinese texts under examination here were not technical experts; they were chroniclers and collectors of anecdotal information, and they did not have the ‘language’ – in the more abstract sense of that Benjamin B. Olshin 129 word – to describe fully the matter at hand. It would be as if we had a contemporary English-speaking poet or historian who lacked any technical knowledge try and describe a new invention or device. The word ‘mirror’ – and that is the precise term used in these Chinese texts – might be metaphorical, standing in for some other metallic or glass-like material or a contraption utilising such material. Even in our contemporary technological age, we often use metaphorical language to describe mechanical devices: a space ‘ship’, a ‘computer’ (although it does much more than simply compute), and so on. The term ‘horseless carriage’ was used to refer to automobiles in the beginning of the twentieth century, as a way of explaining a new technology by using existing language. We cannot rush to assume from these ancient texts an unreasonable technological knowledge on the part of the early Chinese, either.27 However, there may be a few scattered clues in the history of Chinese mirrors to help us interpret these peculiar texts, with two primary elements worth considering. The first is the connection between medicine and mirrors, notable because both our texts have mirrors serving a medical function; the second is the existence in Chinese history of so-called ‘magic mirrors’. Hirth points out several accounts where mirrors were used to prevent or cure sickness, with the methods never sufficiently articulated – at least from a modern perspective – by the Chinese authors.28 Our texts here are somewhat more explicit, in that they at least explain specifically what these mirrors were said to do: reveal the organs of the human body. Despite evidence for a number of uses of mirrors in ancient Chinese sources – including simple reflection, light intensification, rituals, and keeping away evil spirits – the precise medical utilisation of mirrors recounted in the Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi and the Xijing Zaji does not seem to appear in any other accounts in Chinese texts.29 Nor do we find any similar account in Western texts. What we do find in early Chinese is an odd miscellany of medical uses for mirrors, even including bits of them being ground up and consumed orally as a prescription!30 We also find what one writer calls ‘mirror lore’, particularly in the Six Dynasties period, which ran from the early third century to the late sixth century. This ‘lore’ involved a number of different kinds of mirrors with special powers: the zhaoyao jing (‘Mirror that Reveals Demons’), the zhaogu jing (‘Mirror that Reveals Bones’), the wuji jing (‘No Illness Mirror’), the zhishi jing (‘Mirror that Knows [Future] Matters’), and the jianshen jing (‘Mirror that Sees the Spirits’).31 In some sense, then, these strange ‘X-ray’ mirrors are part of a larger cultural context. At the same time, the Chinese certainly had an understanding of mirrors in technical terms – that is, the principles of reflection, inversion and so on.32 But those technical discussions of mirrors that we find in 130 A Revealing Reflection Chinese texts do not appear to match the odd accounts we see here in the Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi and the Xijing Zaji. In another Chinese source, we again find the idea of using a device of some kind to be able to see inside a body. This time, the item in question is not a mirror, and the description and context are less technical. The late ninth-century collection of anecdotes Duyang Zabian (‘Compilation of Miscellanea from Duyang’) by the scholar Su E includes the mention of a huge, shining rock from a country called Rilin – apparently, Japan. This rock revealed the internal organs of a person, aiding the work of a physician in healing them.33 The text also includes some very peculiar descriptions: In the Dali period*, the Rilin country sent as presents luminous beans and dragon-horn hairpins. This country lies forty thousand li northeast across the sea.† In the southwest of the country, there is a strange rock several hundred li square, luminous and clear; it can reflect a person’s five ‘solid’ organs and six ‘hollow’ organs.‡ It is designated the ‘Mirror of the Immortals’§. If a person in this country has an illness, then [the rock] is used to illuminate his body, so as to discover [the problem] in a particular organ. Then, shen cao# is taken, and the person without exception is healed. The size of the beans resembles that of the Chinese green bean, [but] the colour is a dark red. Moreover, their rays [i.e., the rays of light that they emit] can reach several chi in length.34 Apparently, the story of this interesting rock was in circulation earlier; it also is found in almost identical form in the early sixth-century Shu Yi Ji (‘Record of Strange Things’) by Ren Fang, and that seems to have been Su E’s source.35 Again, despite the strangeness of the story, the word used here for mirror is simply the technical term jing. At this point, it may be useful to provide a brief comment on the connections between these Chinese mirrors that are said to be able penetrate the body and the more general idea in early Chinese medicine of seeing inside the body to make a diagnosis and a prognosis, and to heal. One author has noted that, especially in terms of dissection (although it was carried out), ‘anatomy in China never gained dominance as a way of understanding the * This refers to a period from C.E. 766 to C.E. 779 during the Tang Dynasty. † The value of the li varied through various periods of Chinese history, but it can be understood as approximately equivalent to half a kilometer here. ‡ This again refers to the system of organs as found in traditional Chinese medicine, based on the principle of yin and yang. The five ‘solid’ or yin organs are the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidneys, and the six ‘hollow’ or yang organs are the large intestine, small intestine, stomach, gall bladder, urinary bladder, and the ‘triple-warmer’ (the openings of the stomach, small intestine, and the bladder); see Reid, Chinese Herbal Medicine, 32. § The xianren are the Daoist immortals or transcendent beings of Chinese tradition. # Literally ‘spirit herb’ — this is a traditional term for ginseng. Benjamin B. Olshin 131 body. ...’36 Nonetheless, the importance of what was going on inside the body in functional terms, certainly was discussed. One story recounts how the Chinese physician Bian Que warned Duke Huan about a ‘disease which lies in the blood vessels’, and eventually in the bone marrow.37 The story does not make clear how the physician knows this, but it clearly does discuss what one might term ‘levels’ of an illness, deeper and deeper in the body; Bian Que says to the sceptical Duke Huan – who subsequently dies, having delayed treatment too long – the following: When a disease lies in the pores, it can be treated by poultices. When it lies in the blood vessels, it can be treated with needles. When it lies in the stomach and intestines, it can be treated with medicines. But when the disease lies in the bone marrow, not even the God of Life can do anything about it.38 Even though a medical disorder might be internal, as deep as the viscera of the body, Chinese traditional medicine had (and still has) a method of ‘reading’ that disorder on the body’s surface, so to speak, through a complex series of pulse readings at the wrist.39 How does this relate to our stories here of penetrating mirrors? For Chinese physicians, a key question was how to ‘contemplate a body organised by depth’, the ‘levels’ or layers we saw in passage about Bian Que above.40 On the one hand, as one commentator puts it, ‘the skin is an occluding screen’ and blocks the diagnostician from understanding the underlying dysfunction.41 On the other hand, the skin could also reveal what was going on inside, as could the pulse. Chinese physicians used their ‘gaze’ (wang) to make diagnoses, with this ‘gaze’ not only including seeing per se, but also diagnosing through the colour or hue of the skin, smelling the patient’s body and so on.42 One scholar has noted that in early Chinese medicine, ‘it was sufficient to deduce the interior functioning of the body from signs observed externally’, with diagnosis and subsequent treatment ‘based [not only] on vision but also on other senses. ...’43 But the real coup, of course, would be the ability to see directly into the body, and perhaps the story of these penetrating mirrors arose in such a context. That is, the ‘pinnacle of medical acumen’ was wang er zhi; i.e., ‘to gaze and to know’.44 So, while the Chinese medical model clearly comprised levels or layers of the body, and external aspects could reveal those, what if there was a device that could allow the physician’s ‘gaze’ to enter the body unhindered? In early Chinese medicine, a model of illness appeared that was based, in fact, on the concept of ‘dysfunctions within the systems of vessels’ and a ‘deeper physiological dysfunction’.45 Of course, this also suggests that the 132 A Revealing Reflection physician would have desired the best possible methods of perceiving or revealing such an internal dysfunction. It is interesting that we find an oblique connection here to another aspect of mirrors. Chinese medicine not only concerned the body itself and its functions, but the practice was also tightly connected with divination and physiognomy (a situation still found today in places such as Taiwan). This makes sense, given the framework of traditional medicine – ‘reading’ a person as part of a medical diagnosis – along with ‘reading’ a person by looking at their face, their astrological data and so on. Mirrors in the West were used for catoptromancy, as noted earlier; while the Chinese do not seem to have used the ‘medical mirrors’ in this way, they nonetheless connected other forms of divination, through such vehicles as the Yijing, to medicine.46 In a more general sense, too, the idea of ‘reading a face’ to reveal the personality within is not unlike the use of the mirror to reveal both the internal organs – and the inclinations – of one’s concubines! A description concerning a rock with powers similar to the penetrating capacity of the Chinese mirrors is found in an account concerning Jivaka, the physician to the Buddha. Jivaka is reported to have come into the possession of a magic gem that – apparently like a modern fluoroscope – could light up the inside of a person’s body.47 We read that while traveling, Jivaka came upon a man carrying a load of wood to the city, of whom nothing was left but skin and bone, and the whole of whose body was dropping sweat; he said to him, ‘O friend, how came you into such a plight?’ The man replied, ‘I know not. But I have got into this state since I began to carry this load.’ Jivaka carefully inspected the wood, and said, ‘Friend, will you sell this wood?’ ‘Yes!’ ‘For how much money?’ ‘For five hundred Karshapanas.’ Jivaka bought the wood, and when he had examined it, he discovered the gem which brings all beings to belief. The virtue of the gem is of this kind: when it is placed before an invalid, it illuminates him as a lamp lights up all the objects in a house, and so reveals the nature of his malady. When Jivaka had gradually made his way to the Udumbara land*, he found there a man who was measuring with a measure, and who, when he had finished measuring, inflicted a wound upon his head with the measure. When Jivaka saw this, he asked him why he behaved that way. * Literally, ‘land of the fig’; it is not clear to what geographical location this term actually refers. Benjamin B. Olshin 133 ‘My head itches greatly.’ ‘Come here and I will look at it.’ The man lay down and Jivaka examined his head. Then he laid on the man’s head the gem which brings all beings to belief, and it immediately became manifest that there was a centipede* inside. Thereupon Jivaka said, ‘O man, there is a centipede inside your head.’ The man touched Jivaka’s feet and said, ‘Cure me.’ Jivaka promised to do so … Next day Jivaka … opened the skull with the proper instrument, touched the back of the centipede with the heated pincers, and then, when the centipede drew its arms and feet together, he seized it with the pincers and pulled it out.48 As with the Chinese account, this passage contains both fantastical elements – the magical gem – and more technical language; i.e., the description of the surgical procedure, not to mention the diagnostic function of the strange jewel. Another early South Asian tradition speaks of the bhaisajya raja tree – the name means ‘king of healing’ in Sanskrit. This tree was said to contain a gem with the ability to reveal the internal organs of a patient.49 However, just as with other accounts presented here, the precise nature of this ‘penetrating’ visual device is left unexplained.50 Similarly, the ninth century Zhou Qin Xing Ji (‘A Journey through Zhou and Qin’), includes a description of an ‘imperial-consort [who] is said to have worn a luminous jade ring which showed the bone of her finger’.51 In another Chinese story, there are no special gems or other such devices, but rather a certain drug, water or dew which allowed the physician named Bian Que, mentioned earlier, to see the ‘five viscera and the obstructions and knots of the abdomen’.52 Is there a possible explanation for this supposed ability of these early physicians to see inside the human body? Returning to our two original Chinese texts on mirrors, a possible hint might come from the so-called ‘magic mirrors’, mentioned above. ‘Magic mirrors’ were special mirrors created by Chinese craftsmen; these mirrors use various optical phenomena to cast images. The Japanese also created such mirrors, calling them makyō (literally, ‘demon mirrors’).53 A modern study of these rare devices notes that they ‘have the uncanny ability to project patterns from the back when light is shining on the front….’54 Typical ‘magic mirrors’ have cast bronze designs and sometimes written characters on the back (figure 3).55 The reflecting side is convex and made of highly polished bronze. In normal light, this kind of mirror reflects in the * This may refer to a tumor (see B. Laufer, The Prehistory of Aviation (Chicago, 1928), 11) or to Echinococcus granulosus (a kind of tapeworm that can lodge in the brain); see R. M. Pujari, et al., Pride of India: A Glimpse into India’s Scientific Heritage (New Delhi, 2006), 150. 134 A Revealing Reflection Figure 3. A Japanese version of the standard Chinese ‘magic mirror’. On the back side of the mirror is this ornamented surface, with Japanese kanji characters and the images of the birds. The reverse side is a plain, polished reflecting surface. However, when particularly bright light is projected onto the reflecting surface and then cast on a wall, then this ornamental image is actually reflected back, as well. From R.K.G. Temple, ‘The Chinese Scientific Genius: Discoveries and Inventions of an Ancient Civilization’, The Courier (October 1988), 16. devices and ‘penetrating’ devices. Indeed, the image cast by one of these ‘magic mirrors’ is eerily similar to an X-ray image.58 In the case of a Chinese ‘magic mirror’, of course, the mirror is simply casting its own image, and not that of the internal organs of a human body. Yet this still leaves us with a possible interpretation of the mirror described in the Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi and the Xijing Zaji as some kind of trick device. If we examine the brief description in the Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi, typical manner. However, in bright light, one can actually see through the reflecting side. Therefore, these mirrors are able to reflect outwards from the polished side whatever designs and characters are on their back side (figure 4).56 In other words, these mirrors usually have two layers: the first is a lower reflecting surface bearing a design, while the second or upper layer is a polished, half-reflecting surface that also lets light through (figure 5).57 Because of such properties, these types of devices were called tou guang jian; i.e., ‘lightpermeable mirrors’, by the Chinese. Perhaps there is some connection here to the idea of mirrors as both reflecting Figure 4. A photograph of a contemporary ‘magic mirror’ in use. Light comes from a source (not pictured here) and strikes the mirror; the mirror then reflects the light to a screen. An image also appears there – an image that is, essentially, hidden in the mirror. From B.J. Rhodes, ‘Makyoh’, http://www.docbug.com/ Pictures/Makyoh/index.html (accessed 19 January 2013). Benjamin B. Olshin 135 we note that the writer explicitly says that the mirror ‘could reflect objects in the same manner as water’. This indicates a mirror without any special characteristics. But the author adds: ‘Whenever a person had an illness, the mirror could be used to illuminate and see completely any obstructions in his internal organs.’ In the Xijing Zaji, the writer notes that if ‘one were coming directly to face the mirror, then one would see their image reversed’; this also seems Figure 5. Diagram indicating the reflection of a hidden design in a to indicate a typical mir- ‘magic mirror’. The upper layer here reflects light normally from its ror. Again, though, there is surface (see upper arrows). But it also allows light through, particuan additional ability of this larly if that light is striking the upper layer in at a certain angle or mirror: ‘If one touched if light is of certain intensity (see lower arrows); this light goes through the upper layer of the mirror, strikes the design on the one’s heart with the hand, lower layer, and is reflected back up through the upper layer. and approached the mirror, then the colon, stomach, and the five organs were clearly visible [in the mirror].’ We might be able to explain these statements in the context of the wellknown ‘magic mirrors’ described above. Imagine a large, rectangular version of the Chinese ‘magic mirror’. The top layer is the highly polished surface of a typical mirror. The hidden layer is a subtle relief rendering of the torso of a human body with the internal organs depicted. Again, the way such a ‘magic mirror’ works is that while the front appears as a smooth reflecting surface, when sunlight or other kind of bright light is reflected off that surface onto a wall, the design from the hidden layer appears. Thus, our ‘medical mirror’ might have been placed in front of the patient, and then have had a strong light source projected at it (figure 6). An image would have been thrown to the wall – an image that would have appeared to be revealing the internal organs of the patient. In actuality, the image revealed would be that on the hidden layer of the mirror itself. Printed editions of the Huangdi Neijing – the early Chinese medical text mentioned above – include reproductions of early rough drawings of the various human 136 A Revealing Reflection Figure 6. A possible configuration using a Chinese ‘magic mirror’ to render the illusion of seeing the internal organs of a human body. organs, and the image cast on the wall may have looked something like those figures.59 Here, in figure 6, we have used one of those images of the organs from the Huangdi Neijing as the image reflected from the mirror and cast on the wall.60 The Chinese emperor’s mirror – supposed to reveal the mysterious inner workings of the human body – may have been no more than a wellcrafted optical trick. What might this case of these peculiar Chinese mirrors teach us in terms of the history of technology? Most importantly, we learn that descriptions of mechanical devices can be found in a broad variety of literature, from ancient Chinese narratives to Buddhist texts. How those descriptions should be treated is a complex matter, but what we have here is the potential for a broad range of new source material for the history of technology. Historians of technology will need to build new interpretive tools to address these sources, with attempts to understand the descriptions of various ancient devices through the investigation of cultural and linguistic context. Without putting the template of the present onto the past, we can also – as has been done in this paper – try to reconstruct earlier mechanical devices through looking at extant technologies. In that way, we can put together some provisional answers to the eternal question raised by early texts – what were those authors describing? NOTES 1 For some background on the uses of mirrors throughout history, and the complex set of ideas that has developed around them, see J. Baltrus̆aitis, Le miroir: essai sur une légende scientifique: révélations, science-fiction et fallacies (Paris, 1978), and G.F. Hartlaub, Zauber des Spiegels: Geschichte und Bedeutung des Spiegels in der Kunst (Munich, 1951). Benjamin B. Olshin 137 2 Wang Renyu, Kaiyuan Tianbao Yishi, ‘Anecdotes of the Kaiyuan and Tianbao Periods’) (Taipei: Yiwen Yinshuguan Yinxing, 1965–1970); my translation. ‘Kaiyuan’ and ‘Tianbao’ refer to two periods of the reign of the Tang Dynasty emperor Xuanzong, 713 to 741 and 742 to 756, respectively. This work includes a number of tales of peculiar phenomena; see p. 45 of Leo Tak-hung Chan, ‘Text and Talk: Classical Literary Tales in Traditional China and the Context of Casual Oral Storytelling’, Asian Folklore Studies, 56:1 (1997): 33–63. 3 See the mention of this passage in B. Laufer, The Prehistory of Aviation (Chicago, 1928), 88. Laufer does not provide an interpretation of this passage. 4 See p. 33 of Jue Chen, ‘The Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”: An Interpretation of Gujing Ji in the Context of Medieval Chinese Cultural History’, East Asian History, 27 ( June 2004): 33–50. 5 Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’, 44. 6 R.D. McBride, II, ‘A Koreanist’s Musings on the Chinese Yishi Genre’, Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies, 6:1 (April 2006): 31–59, esp. 41–42. 7 For more on Ye Fashan, see Russell Kirkland, ‘Tales Of Thaumaturgy: T’ang Accounts of the Wonder-Worker Yeh Fa-shan’, Monumenta Serica, 40 (1992): 47–86. On the problematic use of the term ‘Daoist’ for such figures as Ye Fashan, see N. Sivin, ‘On the Word ‘Taoist’ as a Source of Perplexity. With Special Reference to the Relations of Science and Religion in Traditional China’, History of Religions,17:3–4 (1978): 303–30, and idem, ‘Taoism and Science’, in N. Sivin, Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections (Brookfield, Vermont, 1995), 1–72. 8 See the discussion of this work in W.H. Nienhauser, Jr., The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature, 2 vols. (Bloomington, Indiana, 1986–1998), I:406–407. Xijing here literally means ‘Western Capital’, and refers to the city of Chang’an and the surrounding area; today it is known as Xi’an. 9 A brief mention of this passage is found in J. Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 4 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 91–92; also note Laufer, Prehistory of Aviation (n. 3 above), 11; and R.L. Gregory, Mirrors in Mind (New York, 1997), 52. See, also, A.G. Wenley, ‘A Chinese Sui Dynasty Mirror’, Artibus Asiae, 25:2–3 (1962): 141–148, esp. 141–142; there, the author notes that this passage is referred to by two other Chinese sources, including a poem inscribed on a mirror now in the Freer Gallery of Art. A short discussion is found in Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’ (n. 4 above), 44–45. 10 Xijing Zaji (‘Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital’) (Taipei, 1979), ch. 3, 3a; another edition of this text, with commentary, is found in Liu Xin, Xijing Zaji Jiaozhu (Shanghai, 1991); the translation here is by the author with the assistance of Thomas Radice, the University of Pennsylvania, and Lin Li-Chuan. The final sentence of this text is somewhat unclear; the connection between Xiang Yu and the fate of the mirror is obscure, although we do know that after the victory of Gaozu over the Qin, Xiang Yu arrived at Xianyang – the location of the palace and the storehouse with the mirror. 11 See Shigehisa Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (New York, 1999), 266. 12 C. Despeux, ‘The Body Revealed: The Contribution of Forensic Medicine to Knowledge and Representation of the Skeleton in China’, in Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: the Warp and the Weft, eds. Francesca Bray, Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann and Georges Métailié (Leiden: Brill), 635–684, esp. 636. 13 This mirror is labelled ‘Mirror with Six Circular Flowers’ (Cleveland Museum of Art, accession number 1995.341). 14 See Ning Yu, ‘Metaphor, Body, and Culture: The Chinese Understanding of Gallbladder and Courage’, Metaphor and Symbol, 18:1 (2003): 13–31, and G. Maciocia, The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists (Edinburgh, 1989), 116. An earlier article on Chinese mirrors also notes that in Chinese culture a mirror could be understood as a ‘a 138 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 A Revealing Reflection thought and crime detector, a precursor of X-ray or a light-emitting object ...’; A.R. Hall, ‘The Early Significance of Chinese Mirrors’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 55:2 ( June 1935): 182–189, esp. 188. On the mention of mirrors in this work, note Wenley, ‘A Chinese Sui Dynasty Mirror’ (n. 9 above), 141–142, and Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’ (n. 4 above), 45, n. 52. On this work generally, see C.E. Reed, A Tang Miscellany: An Introduction to the Youyang Zazu (New York, 2003), as well as C.E. Reed, ‘Motivation and Meaning of a ‘Hodge Podge’: Duan Chengshi’s Youyang zazu’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 123:1 ( January–March 2003): 121–145. See, for example, the brief history and sample images in S. Little and S. Eichman, et al., Taoism and the Arts of China (Chicago, 2000), 140–141. F. Hirth, ‘Chinese Metallic Mirrors, With Notes on Some Ancient Specimens of the Musée Guimet’, in Boas Anniversary Volume: Anthropological Papers Written in Honor of Franz Boas, Professor of Anthropology in Columbia University, Presented to Him on the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of his Doctorate, eds. B. Laufer and H.A. Andrews (New York, 1906), 208–256, esp. 208–212; also see S.V. Cammann, ‘Chinese Mirrors and Chinese Civilization’, Archaeology 2:3 (September 1949): 114–120; R.W. Swallow, Ancient Chinese Bronze Mirrors (Peiping, 1937); and M. Rupert and O.J. Todd, Chinese Bronze Mirrors: A Study based on the Todd Collection of 1,000 Bronze Mirrors Found in the Five Northern Provinces of Suiyuan, Shensi, Shansi, Honan, and Hopei, China (Peiping, 1935). For a brief survey of the development of mirrors in various cultures, see J.M. Enoch, ‘History of Mirrors Dating Back 8000 Years’, Optometry and Vision Science, 83:10 (October 2006): 775–781, which notes the possible foreign origin of Chinese mirrors. On the term jian, see Eugene Yuejin Wang, ‘Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts’, The Art Bulletin, 76:3 (September 1994): 511–534, esp. 511, n. 1. Also note the interesting discussion of mirror symbolism in seventeenth-century Chinese literature in Jing Zhang, ‘In His Thievish Eyes: The Voyeur/Reader in Li Yu’s “The Summer Pavilion”’, Southeast Review of Asian Studies, 34 (2012): 25–42. Of course, the mirror also has a long history as a concept in Eastern philosophy; an early well-known discussion is found in P. Demiéville, ‘Le miroir spirituel’, Sinologica, 1:2 (1947): 112–137. The use of mirrors or mirrored surfaces as magical amulets, etc., is common in many cultures, in locales as diverse as North America, Africa, and Siberia. See, for example, the interesting mention of shamanic uses of such objects in N.J. Saunders, ‘Stealers of Light, Traders in Brilliance: Amerindian Metaphysics in the Mirror of Conquest’, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics (33: PreColumbian States of Being) (Spring 1998): 225–252, esp. 237. See the introductory remarks in Zhou Zhongfu, Sun Shuyun, Han Rubin, and T. Ko, ‘A Study of the Lacquerish Patina (Qi Gu) on Ancient Bronze Mirrors’, in Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine, eds. A.K.L. Chan, G.K. Clancey and Hui-Chieh Loy (Singapore, 2002), 465–469, and Toru Nakano, Tseng Yuho Ecke, and S. Cahill, Bronze Mirrors from Ancient China: Donald H. Graham, Jr. Collection (Honolulu, 1994). Also see the discussion in Kimpei Takeuchi, ‘Ancient Chinese Bronze Mirrors’, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 19:102 (September 1911): 311–313 and 316–319, which includes excellent photographs of some Han and Tang dynasty mirrors. A brief survey can also be found in A. Salmony, ‘Chinese Metal Mirrors: Origin, Usage, and Decoration’, Magazine for the Buffalo Museum of Science, 25 (1945): 96–104. On the decoration of mirrors, see Sueji Umehara and Jiro Harada, ‘The Late Mr. Moriya’s Collection of Ancient Chinese Mirrors’, Artibus Asiae, 18.3–4 (1955): 238–256, as well as the extensive discussion in A. Bulling, ‘The Decoration of Mirrors of the Han Period: A Chronology’, Artibus Asiae. Supplementum, 20 (1960), 3 ff. Hirth, ‘Chinese Metallic Mirrors’ (n. 29 above), 229–230. Concerning different types of early Chinese mirrors, see Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’ (n. 4 above), 35 ff. For a longer discussion on mirrors, magic, and Daoism, see M. Kaltenmark, ‘Miroirs magiques’, in Mélanges de Benjamin B. Olshin 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 139 sinologie offerts à Monsieur Paul Demiéville., II (Paris, 1974), 151–166, as well as E.H. Schafer, ‘A T’ang Taoist Mirror’, Early China, 4 (1978–79): 56–59. Ibid., 223. It may be simply the case, however, that the small round mirrors are more commonly found because the Chinese used them as grave goods; therefore, it is difficult to say what sizes and shapes of mirrors the Chinese actually used in daily life. I would like to thank Nathan Sivin for making this important point. Ibid., 224; there have also been finds of early Chinese square mirrors – see Hirth, ‘Chinese Metallic Mirrors’ (n. 17 above), 182. Square mirrors are also discussed in D. Dohrenwend, ‘The Early Chinese Mirror’, Artibus Asiae, 27:1–2 (1964): 79–98. Also see the comments on large, square mirrors in Chinese lore in Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’ (n. 4 above), 45, n. 52. For some early Western descriptions of distorting mirrors, see, for example, Pliny, Historia naturalis, 33.14.128–130, and Seneca, Naturales quaestiones, 1.5.5. N. Sivin, ‘Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 7, The Social Background. Part 2, General Conclusions and Reflections (review)’, China Review International, 12:2 (2005): 297–307, esp. 303–305. Hirth, ‘Chinese Metallic Mirrors’ (n. 17 above), 188, in passing, notes wryly how a mirror might be credited as ‘a protector against evil ..., a disc for divination like a crystal gazer’s glove, a thought and crime detector, [or] a precursor of X-ray or a light emitting object …’ in early Chinese texts. Hirth, ‘Chinese Metallic Mirrors’ (n. 17 above), 230–232. On the range of uses of mirrors in ancient China, see ibid., 225 ff. Note the comments on these kinds of uses of mirrors in medical practices in Li Shizhen, Bencao Gangmu (‘Compendium of Materia Medica’) (Shanghai, 1959), juan 9, 22–23; also see Hirth, ‘Chinese Metallic Mirrors’ (n. 17 above), 231–232, and M. Pendergast, Mirror Mirror: A History of the Human Love Affair with Reflection (New York, 2003), 20. Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’ (n. 4 above), 41; for the sake of precision, I provide here more literal translations than those given in Chen’s paper. Note, A.C. Graham and N. Sivin, ‘A Systematic Approach to Mohist Optics’, in Chinese Science: Explorations of an Ancient Tradition, eds. Shigeru Nakayama and N. Sivin (Cambridge, MA, 1973), 105–152. See E.H. Schafer, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics (Berkeley, 1963), 37. See the mention of this passage in E.D. Edwards, Chinese Prose Literature of the T’ang Period C.E. 618–906, 2 vols. (London: Arthur Probsthain, 1937), 1.84–85. Schafer, The Golden Peaches, 288, n. 241 and n. 243; also see Chen, ‘Mystery of an “Ancient Mirror”’ (n. 4 above), 45. Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body (n. 11 above), 155. Ibid., 163. The identity of Bian Que is unclear; his real name may have been Qin Yueren, with Bian Que being a title coming from the legendary physician of that name from the age of Huang Di; See I. Veith, trans., The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine (Berkeley, 2002), 3, n. 10. Also note, H.A. Giles, A Chinese Biographical Dictionary (London. 1898), 155 (= entry 396, ‘Ch’in Yüeh-jen), as well as J. Kovacs and P.U. Unschuld, Essential Subtleties on the Silver Sea: The YinHai Jing-Wei: A Chinese Classic on Ophthalmology (Berkeley, 1999), 120–121 and n. 3. In addition, see W.N. Whitney, ‘Notes on the History of Medical Progress in Japan’, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 12:4 ( July 1885): 245–470, esp. 281, n. 54. Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body (n. 11 above), 163. Ibid., 166; this Chinese diagnostic method is unrelated to the Western method of taking the pulse to measure heart rate. See the discussion in E. Hsu, ‘Pulse Diagnostics in the Western Han: How mai and qi Determine bing’, in Innovation in Chinese Medicine, ed. E. Hsu (Cambridge, 2001), 51–91. Ibid., 167. Ibid., 167. 140 A Revealing Reflection 42 Ibid., 167 ff., where Kuriyama provides an interesting discussion of this idea of the ‘gaze’, as well as the importance of the hues of the skin, in diagnosis. 43 Despeux, ‘The Body Revealed’ (n. 23 above), 637. 44 Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body (n. 11 above), 179. 45 D. Harper, ‘Iatromancy, Diagnosis, and Prognosis in Early Chinese Medicine’, in Hsu, ed., Innovation in Chinese Medicine (n. 56 above), 99–120, esp. 99. Also see the discussion of mai in Vivienne Lo, ‘The Influence of Nurturing Life Culture on the Development of Western Han Acumoxa Therapy’, in Hsu, ed., Innovation in Chinese Medicine (n. 56 above), 19–50, esp. 20 ff. Lo also elaborates on the idea of how Chinese medicine included a range of practices, from breath-cultivation to advice on sexual practices. 46 See the discussion in Harper, ‘Iatromancy, Diagnosis’, 100. Also see D. Harper, ‘Physicians and Diviners: The Relation of Divination to the Medicine of the Huangdi neijing’, Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident, 21 (1999): 91–110. 47 A brief mention of this is found in Laufer, The Prehistory of Aviation (n. 3 above), 11. 48 F.A. von Schiefner, trans., Tibetan Tales: Derived from Indian Sources, (London, 1906), 99–100. In another version of this story, Jivaka uses a kind of magical wood to see into a patient’s body; see Laufer, The Prehistory of Aviation (n. 3 above), 11–12, and the detailed discussion in Salguero, 197–201. Also note the brief mention in P.K. Doshi, ‘History of Stereotactic Surgery India’, in Textbook of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, 2d ed., eds. A.M. Lozano, P.L. Gildenberg and R.R. Tasker (Berlin, 2009), 155–169. For more on accounts of Jivaka’s medical knowledge, see C.P. Salguero, ‘The Buddhist Medicine King in Literary Context: Reconsidering an Early Medieval Example of Indian Influence on Chinese Medicine and Surgery’, History of Religions, 48:3 (February 2009): 183–210. 49 K. M. Choksey, Dentistry in Ancient India (Bombay, 1953), 9. 50 For some brief mentions of the Jivaka account, see H.B., ‘Jivaka — Schädelchirurg und “Röntgenarzt” im alten Indien’, Blatter fur Zahnheilkunde. Bulletin Dentaire, 29:7 ( July 1968): 112–115, and K.G. Zysk, Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery (New York, 1991), 55. Concerning other accounts of magical stones, see S.H. Ball, ‘Luminous Gems, Mythical and Real’, The Scientific Monthly, 47:6 (December 1938): 496–505; however, none of the stories that Ball recounts speak of gems that have this ‘x-ray’ quality. 51 Edwards, Chinese Prose Literature (n. 51. Above), 46–47. 52 Salguero, ‘The Buddhist Medicine King’, 201. 53 An early but rather extensive discussion of the similar Japanese devices may be found in W.E. Ayrton and J. Perry, ‘The Magic Mirror of Japan’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 28 (1878–1879): 127–148. Also note W.E. Ayrton, ‘The Mirror of Japan and Its Magic Quality’, Nature, 19:493 (10 April 1879): 539–542, and the report in Notices of the Proceedings at the Meetings of the Members of the Royal Institution of Great Britain ..., 9 (1879–1881): 25–36. There is and even earlier account by D.F. Arago, ‘Presentation of a Chinese ‘Magic Mirror’ to the Académie des Sciences’, Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Science, 19 (1844), 234. On the interest of such mirrors in the West in the nineteenth century, see G.J.N. Gooday and M.F. Low, ‘Technology Transfer and Cultural Exchange: Western Scientists and Engineers Encounter Late Tokugawa and Meiji Japan’, Osiris, 2nd series, 13 (1998): 99–128, esp. 118–119. 54 J.K. Murray and S.E. Cahill, ‘Recent Advances in Understanding the Mystery of Ancient Chinese ‘Magic Mirrors’: A Brief Summary of Chinese Analytical and Experimental Studies’, Chinese Science, 8 (1987): 1–8. For technical discussions of Chinese ‘magic mirrors’, see M.V. Berry, ‘Oriental Magic Mirrors and the Laplacian Image’, European Journal of Physics, 27:1 ( January 2006): 109–118; G. Saines and M.G. Tomilin, ‘Magic Mirrors of the Orient,’ Journal of Optical Technology, 66.8 (August 1999): 758–765; and D.A. Seregin, A.G. Seregin, and M.G. Tomilin, ‘Method of Shaping the Front Profile of Metallic Mirrors with a Given Relief of its Back Surface’, Journal of Optical Technology, 71:2 (February 2004): 121–122. Benjamin B. Olshin 141 55 For a brief discussion of such inscriptions, see B. Karlgren, ‘Early Chinese Mirror Inscriptions’, Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, 6 (1934): 9–74, and W.P. Yetts, ‘Two Chinese Mirrors’, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 74:430 ( January 1939): 22–24 and 26–28. 56 Needham, Science and Civilisation (n. 9 above), 93 ff; also see B. Goldberg, The Mirror and Man (Charlottesville, 1985), fig. 6, and note Gregory, Mirrors in Mind (n. 9 above), 53–54. 57 See ‘Secrets of the Chinese Magic Mirror Replica’, Physics Education, 36:2 (March 2001): 102–107. There are actually two techniques to hide the images. In one, an additional layer of material on the back hides the engraved designs of the mirror. There is also a technique where marks can be made on the reflective surface itself, marks that are visible only when the mirror is used to cast light on a wall; see Gregory, Mirrors in Mind (n. 9 above), 54–55 (caption to fig. 3.3), as well as a the conjectures made in the early nineteenth century by the Scottish inventor Sir David Brewster, in The Chinese: a General Description of the Empire of China and Its Inhabitants, vol. 2 (London, 1840), 83–284. 58 It is interesting to note that in aboriginal art in Australia (and in other locales as well), one finds what is termed ‘X-ray art’ – that is, figures of humans and animals where the bones and internal organs are rendered in some detail; see F. Kirkland and W.W. Newcomb, Jr., The Rock Art of Texas Indians (Austin, 1967), 31, as well as K.K. Chakravarty and R.G. Bednarik, Indian Rock Art and Its Global Context (Delhi, 1997), 183. 59 For some examples of the drawings of human organs in the Huangdi Neijing, see the reproductions in Veith, The Yellow Emporer’s Classic (n. 54 above), 26–27, 28, 31–33, etc. Note especially fig. 10, ‘Position of the Five Viscera, the Stomach, the Large Intestines, and the Small Intestine’, on p. 38, and fig. 13, ‘The Internal Organs’, on p. 41. 60 This is the image reproduced in ibid., 38.