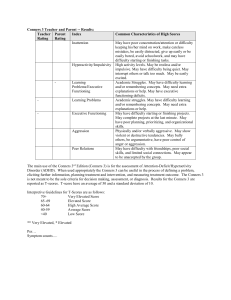

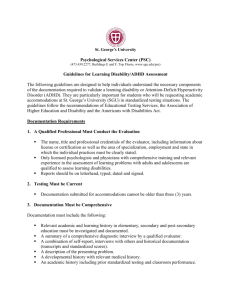

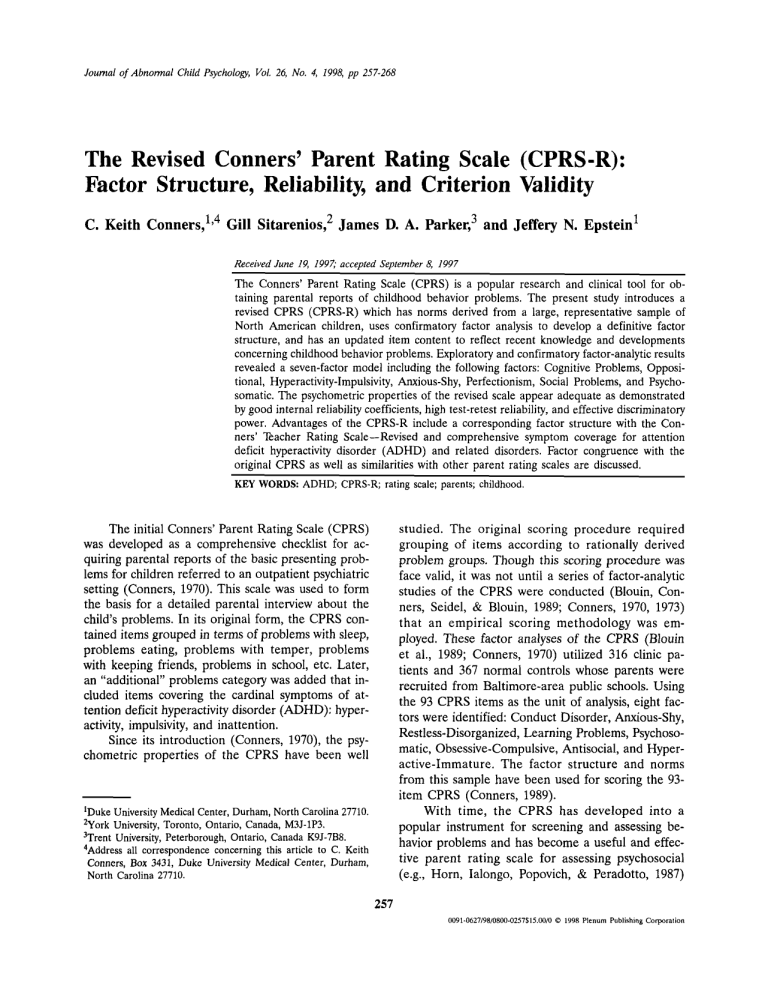

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1998, pp 257-268 The Revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): Factor Structure, Reliability, and Criterion Validity C. Keith Conners,1,4 Gill Sitarenios,2 James D. A. Parker,3 and Jeffery N. Epstein1 Received June 19, 1997; accepted September 8, 1997 The Conners' Parent Rating Scale (CPRS) is a popular research and clinical tool for obtaining parental reports of childhood behavior problems. The present study introduces a revised CPRS (CPRS-R) which has norms derived from a large, representative sample of North American children, uses confirmatory factor analysis to develop a definitive factor structure, and has an updated item content to reflect recent knowledge and developments concerning childhood behavior problems. Exploratory and confirmatory factor-analytic results revealed a seven-factor model including the following factors: Cognitive Problems, Oppositional, Hyperactivity-Impulsivity, Anxious-Shy, Perfectionism, Social Problems, and Psychosomatic. The psychometric properties of the revised scale appear adequate as demonstrated by good internal reliability coefficients, high test-retest reliability, and effective discriminatory power. Advantages of the CPRS-R include a corresponding factor structure with the Conners' Teacher Rating Scale—Revised and comprehensive symptom coverage for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and related disorders. Factor congruence with the original CPRS as well as similarities with other parent rating scales are discussed. KEY WORDS: ADHD; CPRS-R; rating scale; parents; childhood. The initial Conners' Parent Rating Scale (CPRS) was developed as a comprehensive checklist for acquiring parental reports of the basic presenting problems for children referred to an outpatient psychiatric setting (Conners, 1970). This scale was used to form the basis for a detailed parental interview about the child's problems. In its original form, the CPRS contained items grouped in terms of problems with sleep, problems eating, problems with temper, problems with keeping friends, problems in school, etc. Later, an "additional" problems category was added that included items covering the cardinal symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention. Since its introduction (Conners, 1970), the psychometric properties of the CPRS have been well studied. The original scoring procedure required grouping of items according to rationally derived problem groups. Though this scoring procedure was face valid, it was not until a series of factor-analytic studies of the CPRS were conducted (Blouin, Conners, Seidel, & Blouin, 1989; Conners, 1970, 1973) that an empirical scoring methodology was employed. These factor analyses of the CPRS (Blouin et al., 1989; Conners, 1970) utilized 316 clinic patients and 367 normal controls whose parents were recruited from Baltimore-area public schools. Using the 93 CPRS items as the unit of analysis, eight factors were identified: Conduct Disorder, Anxious-Shy, Restless-Disorganized, Learning Problems, Psychosomatic, Obsessive-Compulsive, Antisocial, and Hyperactive-Immature. The factor structure and norms from this sample have been used for scoring the 93item CPRS (Conners, 1989). With time, the CPRS has developed into a popular instrument for screening and assessing behavior problems and has become a useful and effective parent rating scale for assessing psychosocial (e.g., Horn, lalongo, Popovich, & Peradotto, 1987) 1Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710. University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M3J-1P3. 3Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada K9J-7B8. 4Address all correspondence concerning this article to C. Keith Conners, Box 3431, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710. 2York 257 0091-0627/98/0800-0257$15.00/0 C 1998 Plenum Publishing Corporation 258 and drug treatment outcomes in children with disruptive behavior problems (e.g., Fischer & Newby, 1991). Several versions of the CPRS are currently in use including a 48-item questionnaire resulting from a restandardization of a subset from the original scale (Goyette, Conners, & Ulrich, 1978). A 10-item abbreviated questionnaire was also constructed from the items with the best factor loadings (Conners, 1994). Some factor analytic research with the CPRS and its related scales on clinical samples have suggested slightly differing CPRS factor structures (Cohen, DuRant, & Cook, 1988; O'Connor, Foch, Sherry, & Plomin, 1980) than was reported originally. For example, Cohen (Cohen et al., 1988) found that Learning Problems did not form a separate factor in his clinic sample but instead loaded on the Impulsive-Hyperactive factor, thereby forming an overall ADHD factor. Cohen argued that this factor structure was consistent with some investigators contentions that attention (Learning Problems) and hyperactivity (Impulsivity-Hyperactivity) tend to present as a single disorder in clinical populations (Cohen & Hynd, 1986; Werry, Sprague, & Cohen, 1975). Despite some differences in factor structure across studies, the psychometric properties of the CPRS have made this scale an attractive research and clinical tool. Good reliability of the CPRS as assessed by test-retest (Glow, Glow, & Rump, 1982) and interrater reliability (Conners, 1973) has been established. In addition, the CPRS's concurrent validity is well established by high correlations with similar factors on other parent rating scales, such as the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983; Mash & Johnston, 1983) and Behavior Problem Checklist (Arnold, Barnebey, & Smeltzer, 1981; Campbell & Steinert, 1978). Further evidence of its validity comes from research demonstrating the discriminatory power of the CPRS in differentiating behaviorally disordered children from normal children (Prior & Wood, 1983; Ross & Ross, 1976, 1982) and between differing types of behavioral disorders (Conners, 1970; Kuehne, Kehle, & McMahon, 1987; Leon, Kendall, & Garber, 1980). Though the CPRS continues to experience widespread use by both clinicians and researchers, several issues indicate that an update and restandardization of the CPRS is necessary. First, current norms for the CPRS are based on normative data from a relatively small sample of Baltimore-area school children gathered in the 1960s. The size, geographical representation, and demographics of this sample are prob- Conners, Sitarenios, Parker and Epstein ably not representative of the wide range of children for whom the CPRS is applied today. Second, as discussed above, the factor structure of the CPRS has varied across studies. No studies to date have ever tested and confirmed the CPRS factor structure using cross-validation, replication, or confirmatory factor analysis. Therefore, a definitive factor structure has not been established. Third, the original item content was developed to provide a comprehensive and broad assessment of childhood behaviors, including feeding, eating, and sleeping problems among others. But many of these items are unrelated to the most common behavior problems typically encountered. The scale has also been criticized for lacking sufficient emphasis on internalizing states such as anxiety and depression. Extensive use has shown that a briefer and more focused scale would be useful. Scale brevity and focus is relevant for ease of use and increasing parent compliance. This becomes increasingly important when repeated administration is necessary (i.e., when monitoring behavioral or pharmacologic interventions ). Last, item content of the CPRS has not been updated to reflect the accumulating body of knowledge about behavior disorders. The original item content was reflective of conceptualizations of behavioral problems during the 1960s-1970's. Some ADHD-related behaviors (e.g., academic problems) and ADHD symptoms (e.g. excessive talking) were not included because neither well-developed ADHD criteria nor information about comorbid disorders were available at the time of scale development. Thus, the goal of the present study was to revise the CPRS by (1) deriving norms using a large, representative sample of North American children; (2) using confirmatory factor analysis to develop a definitive factor structure; (3) focusing the revised scales on behaviors that are directly related to ADHD and its associated behaviors; and (4) updating the item content to reflect recent knowledge and developments concerning ADHD. In addition, the reliability and validity of this revised scale was examined. STUDY 1: SCALE DEVELOPMENT Method Subjects Subjects consisted of 2,200 students (1,099 males and 1,101 females) ranging in age from 3 to 17 years. 259 Revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale Females had a mean age of 10.43 years (SD = 3.73) and males a mean age of 10.09 years (SD = 3.68). The median annual household income of the students rated by their parents was between $40,001 and $50,000. Eighty-four percent of the students were European American, 5% African American, 4% Hispanic, and 7% other. Procedure Officials and school psychologists from approximately 200 schools throughout Canada and the United States functioned as site coordinators for the present study. Site coordinators were provided with consent forms, questionnaires, and forms which outlined the background of the study to parents and students in the school. Parent who agreed to participate were asked to rate as many of their schoolage children as possible. Children and adolescents in special education classes were not included in this study. Many new items were created in order to strengthen some of the weaker factors (e.g., internalizing behaviors) and those previously underrepresented. A preliminary item analysis on approximately 100 ratings was used to remove items with restricted variance or comments regarding readability, interpretability, or vagueness. Parents were asked to rate each item on the 193 item-pool using 4-point Likert scales (ranging from 0 for not at all true to 3 for very much true). Completed forms were returned to the site coordinators and forwarded to the authors. Statistical Analyses The sample was randomly divided into a derivation sample (n = 1,100) and a replication sample (n = 1,100). The 193 items from the derivation sample were intercorrelated and the resulting matrix subjected to principal axis factoring. A series of factor analyses was conducted to determine what items should be retained. Items were included on the final version of the scale if the following criteria were met: (1) Items had to load significantly (greater than .30) on a given factor and lower than .30 on the other factors, and (2) following the rational approach to scale construction, an item was eliminated if it lacked conceptual coherence with its factor. Scree test and eigenvalues (> 1.0) were used to select the number of factors for rotation (Cattell, 1978). In addition, we employed the split-half factor comparabilities method (Everett, 1983) to determine the most reliable factor solution. The factor structure for the CPRS-R was tested in the replication sample (n = 1,100) using confirmatory factor analysis with EQS for Windows (version 5.1; Bentler, 1995). As recommended by Cole (1987) and Marsh, Balla, and McDonald (1988), multiple criteria were used to assess the goodnessof-fit of the six-factor model: the goodness-of-fit index (GFI; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1986), the adjusted GFI (AGFI; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1986), and the root mean-square residual (RMS). Based on the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbing (1984), Cole (1987), and Marsh et al. (1988), the following criteria were used to indicate the goodness-of-fit of the model to the data: GFI > .85; AGFI > .80; RMS < .01. Results Scale Development The correlation matrix of the 193 item-pool was subjected to principal-axis factoring and scree test and eigenvalue greater than 1.0 criteria (Cattell, 1978). These criteria indicated the relative suitability of six, seven, and eight factors for rotation. In order to determine the most reliable number of factors to retain for rotation, the split-half factor comparabilities method was applied (Everett, 1983). To this end, the derivation sample was randomly split into two subsamples (n = 550 and 550). For each sample six-, seven-, and eight-factor solutions were rotated to solution (varimax rotation). Results indicated that the seven-factor solution produced the highest factor comparability coefficients. Based on these results, the entire derivation sample was factor-analyzed and seven factors were rotated to a varimax solution. Items were eliminated from further analyses because they failed to load (above .30) on any one factor, or because they loaded above .30 on more than one factor (in several cases items were retained that double-loaded above .30 because there was a high loading for the target factor and the loading for the second factor was just above .30). The remaining items were factor-analyzed and seven factors rotated to a varimax solution. This procedure was repeated until 57 items remained. Table I presents the factor loadings, eigenvalues, and percentage of variance for 260 Conners, Sitarenios, Parker and Epstein Table I. Rotated Factor Loadings from a Principal Axis Factor Analysis of Items from the Conners' Parent Rating Scale— Revised (CPRS-R) (Derivation Sample, n = 1,100) Factors CPRS-R items 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 .047 .019 .106 .161 .100 .049 .153 -.022 .110 .100 .061 .073 .019 .027 -.013 .006 -.062 .033 -.047 -.050 -.008 -.105 -.021 .113 .048 .103 .111 .106 .144 .074 .099 .030 .082 .080 .110 .095 .078 .076 .057 .090 .073 .142 .080 .095 .069 .130 .121 .106 .049 .112 .089 .107 .069 .177 .109 .107 .148 .065 .057 .081 .087 .017 -.006 .117 .002 .055 -.015 .132 .049 .125 .075 .046 .117 .157 .093 .151 .112 .204 .117 .116 .161 .061 .120 .153 .072 .096 .052 .012 .135 .106 .174 .105 .130 .117 -.063 .138 .123 -.051 -.028 .072 .055 -.012 .023 .107 .112 .024 .024 .052 .126 .138 -.028 .219 .137 .120 .030 .019 -.006 .114 .056 .027 .003 .114 .094 .726 .710 .700 .626 .630 .521 .538 .481 .141 .105 .067 .032 .129 .144 .146 .061 .081 .114 .114 .004 .079 -.036 .179 .145 .116 .053 .079 .107 .190 .086 .034 .140 .117 .067 .099 .218 .151 -.053 .119 .740 .698 .570 .694 .632 .647 .612 .070 .039 -.054 .095 .075 .042 .052 .075 .056 -.023 .041 .029 .087 .052 (c.ontinued) Factor 1: Cognitive Problems Difficulty completing Fails to complete Needs supervision Avoids mental effort Trouble concentrating Careless mistakes Arithmetic problems Sloppy handwriting Fails to finish Forgetful Loses things Poor spelling .793 .760 .752 .737 .691 .686 .557 .604 .620 .600 .581 .545 Angry Argues Loses temper Irritable Defies adults Annoy people Touchy Blames others Spiteful Fights .161 .194 .195 .212 .213 .210 .162 .273 .190 .069 180 56 178 172 183 52 179 182 60 Always on the go Hard to control Runs excessively Restless Difficulty waiting Run around at meals Difficulty being quiet Blurts out answers Excitable .192 .149 .170 .196 .228 .063 .225 .230 .259 95 90 89 91 94 170 138 156 Timid Afraid of people Afraid of new situations Afraid of being alone Many fears Afraid of the dark Shy Clings to parents .055 .051 .174 .048 .162 .015 .084 .111 114 117 116 85 78 81 112 111 84 87 175 110 .207 .232 .130 .280 .175 .209 .053 .119 .311 .294 .204 .024 .063 .135 .240 .230 .295 .184 .010 .074 .288 .269 .257 .064 007 Factor 2: Oppositional 48 43 42 20 44 45 47 46 24 4 .723 .638 .653 .648 .643 .611 .639 .575 .581 .471 .122 .187 .244 .187 .275 .200 .085 .173 .161 .181 Factor 3: Hyperactivity-Impulsivity .121 .240 .190 .137 .275 .088 .284 .218 .294 .708 .708 .728 .637 .644 .577 .627 .506 .577 Factor 4: Anxious-Shy .136 .165 .187 .037 .241 .055 .053 .037 .038 .027 .063 .193 .100 .205 -.033 .274 Factor 5: Perfectionism 130 133 135 131 137 132 136 Everything just so Keeps checking Fussy Things done same way Has rituals Sets high goals Upset if things moved -.114 -.028 .036 .002 .052 -.148 .043 .078 -.029 -.024 .096 .112 -.066 .179 .072 .038 -.008 .148 .094 -.032 -.043 Revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale 261 Table I. (Continued) Factors CPRS-R items 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 .153 .046 .272 .070 .215 .048 .045 .102 .075 .096 .793 .725 .704 .636 .424 .012 .043 .029 .133 .162 .101 .144 .120 .032 .181 .161 .066 .095 .011 .098 -.024 .098 .011 .055 -.022 .125 .060 .110 .750 .616 .648 .452 .531 .306 Factor 6: Social Problems 140 143 142 147 144 No friends Loses friends Does not make friends Doesn't get invited Feels inferior .162 .203 .197 .137 .242 123 124 125 122 128 126. Stomach aches Aches and pains Aches before school Headaches Complains Seems tired .083 .091 .166 .151 .144 .187 .164 .212 .142 .180 .211 .112 .192 .120 .115 -.004 Factor 7: Psychosomatic Eigenvalues % of Variance 14.67 25.7 .137 .154 .086 .129 .174 .243 .094 .032 .069 .002 .118 -.040 4.20 2.59 2.15 2.11 1.86 1.37 7.4 4.5 3.8 3.7 3.3 2.4 each factor for this analysis. The seven rotated factors accounted for 50.8% of the total variance. The first factor accounted for 25.7% of the total variance and the 12 items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap a "cognitive problems" dimension. The second factor accounted for 7.4% of the total variance and the 10 items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap an "oppositional" dimension. The third factor accounted for 4.5% of the total variance and the nine items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap a "hyperactivity-impulsivity" dimension. The fourth factor accounted for 3.8% of the total variance and the eight items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap an "anxious/shy" dimension. The fifth factor accounted for 3.7% of the total variance and the seven items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap a "perfectionism" dimension. The sixth factor accounted for 3.3% of the total variance and the five items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap a "social problems" dimension. The seventh factor accounted for 2.4% of the total variance and the six items that loaded on this factor appeared to tap a "psychosomatic" dimension. and RMS = .0291).5 All of the parameter estimates between items and factors were significant: For the Oppositional Factor, the 10-parameter estimates ranged from .603 to .792 (mean = .720); for the Cognitive Problems factor, the 12-parameter estimates ranged from .529 to .866 (mean = .743); for the Hyperactivity-impulsivity factor, the nine-parameter estimates ranged from .610 to .791 (mean = .715); for the Anxious/Shy factor, the eight-parameter estimates ranged from .518 to .752 (mean = .644); for the Perfectionism factor, the seven-parameter estimates ranged from .528 to .699 (mean = .643); for the Social Problems factor, the five-parameter estimates ranged from .597 to .855 (mean = .767); for the Psychosomatic factor, the six-parameter estimates ranged from .476 to .751 (mean = .632). STUDY 2: RELIABILITY, INTERNAL CONSISTENCY, AND AGE AND SEX DIFFERENCES Method Participants Factor Replication The seven-factor oblique model for the 57-item CPRS-R was tested using confirmatory factor analysis on the cross-validation sample (n = 1,100). All three goodness-of-fit indicators suggested that the model had good fit to the data (GFI = .863, AGFI = .849, The sample consisted of the 2,200 students used in Study 1 (1,101 males and 1,099 females). A subset 5 The model had to be slightly modified with the addition of selected correlated errors (0.9% of possible correlated errors). See Tanaka and Huba (1984) for a discussion of this procedure. The mean for these error correlation was .244 (range = .134 to .399). 262 Conners, Sitarenios, Parker and Epstein Table II. Internal Reliability Coefficients for Scales on the Conners' Parent Rating Scale-Revised (CPRS-R) 3 to 7 years 8 to 12 years 13 to 17 years Male Female Male Female Male Female Oppositional Cognitive Problems Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Anxious/Shy Perfectionism Social Problems Psychosomatic .89 .92 .92 .86 .86 .85 .77 .88 .92 .91 .86 .88 .87 .83 .92 .94 .91 .85 .82 .88 .75 .91 .92 .83 .85 .83 .81 .79 .92 .93 .85 .81 .84 .87 .82 .90 .93 .75 .82 .82 .85 .75 n 307 286 479 467 315 346 CPRS-R Scale tions: .60 (p < .05) for Oppositional, .78 (p < .05) for Cognitive Problems, .71 (p < .05) for Hyperactivity-Impulsivity, .42 (p < .05) for Anxious/Shy, .60 (p < .05) for Perfectionism, .13 (p = n.s.) for Social Problems, and .55 (p < .05) for Psychosomatic. Means and standard deviations for the various CPRS-R scales (separately by sex and age group) are presented in Table III. A series of (Sex x Age Group) analyses of variance were conducted with each of the CPRS-R scales as the dependent variable. For the Oppositional scale, males were rated significantly higher than females [F(l, 2,194) = 14.55, p < .001], but the main effect for age group and the interaction were not significant. For the Cognitive Problems scale, males were rated significantly higher than females [F(l, 2,194) = of 49 children (23 males and 26 females) were rated by their parent on the CPRS-R on two occasions approximately 6 weeks apart. Results Table II presents the internal reliability coefficients for the CPRS-R scales, separately for 3- to 7year-olds, 8- to 12-year-olds, and 13- to 17-year-olds. Coefficient alphas for the seven scales on the CPRSR ranged from .75 to .94 for males and .75 to .93 for females, suggesting that the scales on the CPRSR have excellent internal reliability. Using Pearson product-moment correlations (n = 50), the CPRS-R scales had the following 6-week test-retest correla- Table III. Means and Standard Deviations for Scales on the Conners' Parent Rating Scale— Revised (CPRS-R) 3 to 7 years CPRS-R Scale Oppositional Mean SD Cognitive Problems Mean SD Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Mean SD Anxious/Shy Mean SD Perfectionism Mean SD Social Problems Psychosomatic Total 13 to 17 years Females Males Females Males Females Males Females Males 4.89 (4.44) 5.61 (5.00) 4.59 (4.88) 5.89 (5.68) 4.82 (4.96) 5.37 (5.53) 4.74 (4.79) 5.66 (5.46) 3.84 (5.80) 5.93 (7.07) 4.14 (5.69) 8.33 (8.28) 4.87 (6.79) 8.31 (8.29) 4.29 (6.09) 7.65 (8.03) 3.60 (4.75) 4.83 (5.79) 1.54 (2.65) 3.18 (4.74) 1.26 (2.18) 1.93 (3.28) 1.99 (3.36) 3.28 (4.83) 4.78 (4.33) 4.19 (4.28) 2.71 (3.45) 2.89 (3.72) 2.12 (3.04) 1.50 (2.66) 3.06 (3.73) 2.85 (3.76) 3.97 (4.23) 3.42 (3.94) 3.73 (3.80) 3.36 (3.56) 4.52 (4.28) 4.15 (4.29) 4.04 (4.08) 3.60 (3.90) .78 .86 .88 1.2 SD (1.82) (2.03) (1.77) (2.43) 11.0 (2.13) 11.0 (2.32) 8.89 (1.90) 1.07 (2.29) Mean 1.60 (2.42) 1.24 (2.04) 1.55 (2.23) 1.62 (2.16) 1.92 (2.32) 1.58 (2.43) 1.68 (2.31) 1.50 (2.21) 286 307 467 479 346 315 1,099 1,101 Mean SD n 8 to 12 years 263 Revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale Table IV. Correlations Among Scales on the Conners' Parent Rating Scale— Revised (CPRS-R)a 1 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Oppositional Cognitive Problems Hyperbctivity-Impulsivity Anxious/Shy Perfectionism Social Problems Psychosomatic 2 .57b .50b .51b .37b .13b .43b .44b 3 — .58b .55b .49b .30b -.02 .45b .42b .36b .12b .35b .33b — 4 5 6 7 .38b .33b .41b .17b .49b .44b .42b .40b .17b — .40b .36b .24b .34b .15b .33b .34b — .26b .39b .34b .00 .17b .27b — .12b .14b aMales (n = 1,101) above the diagonal and females (n = 1,099) below. b p < .01. 110.12, p < .001], a significant main effect was found for age group [F(2, 2,194) = 10.16, p < .001], and the interaction of Group Age x Sex was significant [F(2, 2,194) = 4.04, p < .05]. Using univariate analysis of variance for age group, the 3- to 7-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 8- to 12-yearolds [F(l, 2,194) = 13.29, p < .001] and the 13- to 17-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 18.09, p < .001]. For the Hyperactivity-Impulsivity scale, males were rated significantly higher than females [F(l, 2,194) = 45.23, p < .001] and a significant main effect was found for age group [F(2, 2,194) = 69.70, p < .001]; the interaction was not significant. Using univariate analysis of variance for age group, the 3to 7-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 8- to 12-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 77.31, p < .05] and the 13- to 17-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 131.87, p < .001], and the 8- to 12-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 13- to 17-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 13.93, p < .001]. For the anxious/shy scale, females were rated significantly higher than males [F(l, 2,194) = 4.81, p < .05], a significant main effect was found for age group [F(2, 2,194) = 87.43, p < .001], and the interaction was significant [F(2, 2,194) = 3.24, p < .05]. Using univariate analysis of variance for age group, the 3- to 7-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 8- to 12-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 79.22, p < .001] and the 13- to 17-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 171.79, p < .001], and the 8- to 12-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 13- to 17-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 29.51, p < .001]. For the Perfectionism scale, females were rated significantly higher than males [F(l, 2,194) = 6.17, p < .05] and a significant main effect was found for age group [F(2, 2,194) = 8.12, p < .001]; the interaction was not significant. Using univariate analysis of variance for age group, the 13- to 17-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 3- to 7-year- olds [F(1, 2,194) = 8.03, p < .005] and the 8- to 12year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 15.43, p < .001]. For the Social Problems scale, the main effects for sex and age group, and the effect for the interaction, were not significant. For the Psychosomatic scale, females were rated significantly higher than males [F(l, 2,194) = 4.78, p < .05] and a significant main effect was found for age group [F(2, 2,194) = 3.34, p < .05]; the interaction was not significant. Using univariate analysis of variance for age group, the 3- to 7-year-olds were rated significantly higher than the 13- to 17-year-olds [F(l, 2,194) = 6.67, p < .01]. The intercorrelation matrix of the CPRS-R scales is presented in Table IV , separately for males and females. To examine possible gender differences in the pattern of intercorrelations, the equality of the correlation matrices was tested using EQS for Windows (version 5.1; Bentler, 1995). The criteria for determining the equality of the correlation matrices were a nonnormed fit index (NNFI; Bentler & Bonett, 1980) greater than .900 and a comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) greater than .900. Results indicated that the pattern of intercorrelations for the CPRS-R scales was virtually identical across the sexes (NNFI = .988 and CFI = .989). A similar pattern of results was found when the equality of the correlation matrices among the three age groups was tested using EQS (NNFI = .956 and CFI = .962). STUDY 3: CRITERION VALIDITY Method Participants Two groups of children were used in the present study. The first group consisted of 91 children (68 264 Conners, Sitarenios, Parker and Epstein Table V. Means and Standard Deviations for the Non-ADHD (n = 91) and ADHD (n = 91) Groups on the Conners' Parent Rating Scale— Revised (CPRS-R)a Non-ADHD CPRS-R Scale Oppositional Cognitive Problems Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Anxious/Shy Perfectionism Social Problems Psychosomatic ADHD Mean (SD) Mean (SD) t P 4.26 5.17 1.97 2.43 3.78 0.62 1.28 (3.99) (6.50) (3.43) (2.90) (4.21) (1.19) (2.07) 10.83 22.64 10.65 4.14 2.91 3.92 3.04 (6.99) (7.97) (6.70) (3.89) (3.83) (4.03) (3.07) 7.79 16.20 11.00 3.36 1.45 7.49 4.55 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 .149 <.001 <.001 aADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. males and 23 females) who met the following criteria: (a) parent and/or teacher referral to an outpatient ADHD clinic due to reported problems with inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity; (b) independent diagnosis of ADHD by psychologist and/or psychiatrist using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Neutral Disorders (4th ed.) (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for ADHD. Eighty-four percent of the participants were European American, 8.8% were African American, 1.1% were Hispanic, and 6.1% were other; the mean age was 10.16 years (SD = 3.40). The second group (non-ADHD) consisted of 91 children (68 males and 23 females) from Studies 1 and 2 who were randomly selected and matched with the ADHD sample on the basis of age, sex, and ethnicity. Procedure For participants in the ADHD sample, the CPRS-R information was obtained as part of routine clinical assessment. Results Table V presents means and standard deviations for the CPRS-R scales for the ADHD and nonADHD groups. The ADHD group was rated significantly higher (using Mests) than the non-ADHD group on the Oppositional scale, the Cognitive Problems scale, the Hyperactivity-Impulsivity scale, the Anxious/Shy scale, the Social Problems scale, and the Psychosomatic scale; there was no significant difference between the two groups on the Perfectionism scale. A direct discriminant function analysis was performed using CPRS-R scales as predictors of mem- bership in the two groups (ADHD vs. non-ADHD). Discriminant function scores were subsequently used to classify the 182 children into ADHD and nonADHD groups. The results of this classification are presented in Table VI. Following the definitions and procedures outlined by Kessel and Zimmerman (1993), a variety of diagnostic efficiency statistics were calculated for the CPRS-R from these classification results: sensitivity was 92.3%, specificity was 94.5%, positive predictive power was 94.4%, negative predictive power was 92.5%, false positive rate was 5.5%, false negative rate was 7.7%, kappa was .868, and the overall correct classification rate was 93.4%. GENERAL DISCUSSION Redevelopment and restandardization of the CPRS has produced a revised parent rating scale with better psychometric properties than previous versions. Scale construction was performed systematically, comprehensively, and in accordance with psychometric standards (American Psychological Association, 1985), resulting in a definitive factor structure and representative normative data. In addition, the revised scale's content contains fewer items, yet provides a more comprehensive assessment and specific focus on ADHD-related behaviors than the Table VI. Classification Results (ADHD vs. Non-ADHD) for the Conners' Parent Rating Scale— Revised (CPRS-R)a Diagnosis Test ADHD Non-ADHD Total Present Absent 84 7 5 86 89 93 Total 91 91 182 aADHD = attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale original CPRS. With greater focus on ADHD-related behaviors and concordance between scale items and current conceptualizations of ADHD, the CPRS-R provides better discriminatory power for detecting ADHD children than previous scale versions. Examination of the revised scale in terms of its functional uses suggests that the CPRS-R will provide researchers and clinicians an effective tool for assessing parental perceptions of ADHD-related behaviors. The foremost function of the CPRS-R will be as a screening tool or as an adjunctive instrument to a comprehensive assessment. This study's results suggest that the CPRS-R is effective at discriminating ADHD children from normal children. Further, ratings of children throughout North America can be compared to normative data from a large, representative sample in order to provide a measure of deviance or severity. Reliability estimates also suggest that accurate measures of parental perceptions may be obtained. Consistent with the original forms' use (Conners, 1994), the CPRS-R can also be used as a clinician checklist when performing a clinical interview. Indeed, the factor structure of the CPRS-R represents several categories of behavior which are either directly related to ADHD symptoms (e.g., hyperactivity) or comorbid with ADHD (e.g., oppositional behavior) thereby providing a clinician with problem domains upon which an interview could be focused. The other major use of the CPRS-R will likely be to monitor treatment and to assess treatment outcome. Additional research needs to be conducted to determine the utility of the CPRS-R in accomplishing this function. However, since the CPRS-R factor structure comprehensively assesses many ADHD-related behaviors, some of which (e.g., HyperactivityImpulsivity) have proven to be susceptible to change as a result of typical ADHD interventions (e.g., psychostimulant treatment), it seems likely that the CPRS-R will provide a behavior-specific measure of treatment outcome. In comparison to the factor structure used for scoring the original CPRS (Blouin et al, 1989), the CPRS-R factor structure is quite similar, especially in regard to factors assessing internalizing symptomatology. The CPRS-R factor structure retains the Psychosomatic and Anxious/Shy factors from the original scale both in form and name. The CPRS-R Perfectionism factor is largely the same as the original Obsessive/Compulsive factor except that the label has been modified to more accurately reflect the behavioral symptomatology encompassed by this factor. 265 In regards to externalizing behavior factors, the factor structure has changed somewhat. A new Cognitive Problems factor includes symptoms consistent with the DSM-IV ADHD inattentive domain. This factor also encompasses academic difficulties with items assessing handwriting, spelling, and arithmetic. The clustering of academic difficulties with inattention problems on the same factor is supported by the factor structure derived from a national sample of parent ratings (Achenbach, Howell, Quay, & Conners, 1991) and is concordant with the factor structure of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale—Revised (Conners, Sitarenios, Parker, & Epstein, 1998). As suggested by Conners et al. (1998), this clustering of academic and inattention problems may be explained by the high relation between academic achievement and inattention problems in elementary school children (Hinshaw, 1991). The original CPRS did not adequately assess for either inattention or academic achievement; therefore there are no corresponding factors on the original CPRS. In fact, the lone CPRS inattention item, fails to finish things s/he startsshort attention span, loads on both the CPRS Conduct Problem and Hyperactive/Immature factors. The other domain of ADHD symptoms, hyperactive/impulsivity, is assessed by the CPRS-R Hyperactivity factor. This factor has items covering both hyperactive and impulsive symptoms. The original CPRS had two factors which assessed these categories of behaviors labeled Hyperactive/Immature and Restless/Disorganized. Both factors contained extraneous behaviors discordant with their label (e.g., "cries easily" on the Hyperactive/Immature factor) and neither comprehensively assessed hyperactive or impulsive symptoms. However, the CPRS-R Hyperactivity factor contains items which all relate to the hyperactive/impulsive domain of behavior and which assess a wide variety of symptoms related to this symptom cluster. Thus scores on this scale are much more reflective of hyperactive/impulsive symptoms. Similarly, the original CPRS had a Conduct Disorder factor and Antisocial factor, both of which assessed symptoms consistent with Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder diagnoses. However, problems with the CPRS Conduct Disorder factor included the fact that it assessed a wide variety of externalizing symptoms other than those behaviors associated with Conduct Disorder including items associated with ADHD. Thus, this factor was more a measure of externalizing behavior than CD specifically. The CPRS-R has a single Oppositional factor that more accurately and specifically 266 assesses behaviors consistent with ODD and CD and excludes those externalizing behaviors associated with ADHD thus providing a more useful and distinct measure of oppositional behavior. The last factor on the CPRS-R is the Social Problems factor, which was absent on the original CPRS. Since social problems are often present in children with externalizing behaviors, this symptom category is extremely important to assess. Indeed, several investigators have suggested the relevance of social difficulties in the long-term outcome and prognosis of ADHD children (Barkley, 1990; Landau & Moore, 1991). However, the relatively low test-retest reliability of this scale suggests caution in its use and the need to develop a more reliable version of this scale. A useful advantage of the CPRS-R factor structure is that it is similar in factor content to the revised Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS-R; Conners et al., 1998). All of the CPRS-R factors correspond with CTRS-R factors.6 Corresponding factors across these two scales provide the opportunity to directly compare parent and teacher ratings of a specific behavioral domain, using norms obtained on the same children, thus providing measures of cross-informant consistency and possibly providing information about situation-specific behavioral patterns across school and home environments. Indeed, assessing problems across multiple environments is a requirement for a DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis. Gender differences on the CPRS-R revealed higher ratings for males on the Cognitive Problems, Hyperactivity-Impulsivity, and Oppositional factors while girls were rated higher on the Anxious/Shy, Psychosomatic, and Perfectionism factors. These gender differences on the CPRS-R corroborate the common finding that boys tend to be rated higher on Externalizing factors while girls are rated higher on Internalizing factors (Achenbach et al., 1991; Anderson, Williams, McGee, & Silva, 1987; Costello et al., 1985; Offord, Boyle, Szatmari, Rae, et al., 1987; Velez, Johnson, & Cohen, 1989). Achenbach et al. (1991) pointed out that sex differences on rating scales are small in normative samples, but that, in troubled children, these differences become large since there is a large degree of externalizing problems in troubled boys and internalizing problems in troubled girls. While this may be true, the observed 6 There is no corresponding Psychosomatic factor on the CTRS-R since teachers were not asked to rate these items because of experience suggesting that they did so unreliably. Conners, Sitarenios, Parker and Epstein sex differences in our normative sample, especially on Externalizing factors, were quite large and suggest a normative trend for males to express a far greater amount of externalizing symptoms than females. Age differences were found on several factors with children receiving lower ratings with age on the Cognitive Problems, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity, Anxious/Shy, and Psychosomatic factors. Similar declines in problem scores have been found in other studies (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981; Achenbach, Hensley, Phares, & Grayson, 1990). This finding likely reflects normative developmental trends in which certain behaviors (e.g., excitable) generally decrease with age. The CPRS-R Perfectionism factor showed an opposite effect, with higher ratings with increased age. This reverse effect possibly reflects the phenomenon that many developmentally sanctioned obsessive-compulsive behaviors occur in early childhood (e.g., elaborate bedtime rituals) and are not likely to be rated by parents as inappropriate or problem behavior (March, Leonard, & Swedo, 1995). However, as children grow older, ritualistic and perfectionistic behaviors become less socially accepted, thus resulting in higher ratings on this factor for older children. In comparison to other parent rating scales, the CPRS-R has comparable psychometric properties yet measures ADHD and its associated behaviors more specifically and comprehensively. Specifically, in comparison to two of the more popular parent rating scales, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (RBPC), the CPRS-R is the only checklist that contains scales related to both domains of ADHD behaviors, inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. The CBCL has a single factor labeled Hyperactivity and the RBPC has an Attention Problems-Immaturity factor. Measuring the severity of both domains of ADHD behaviors seems necessary for both comprehensive descriptive and diagnostic purposes. The CBCL includes factors not found in the CPRS-R, including Depressed, Immature, Sexual, and Uncommunicative. Despite attempts to enlarge the CPRS-R item pool so as to reveal a factor of depression, those items repeatedly became subsumed under the Anxiety factor. Items relating to immaturity typically attached themselves to the Cognitive Problems factor or were unstable in replication studies. Social communication problems are included in the Social Problems factor. Long experience with items regarding precocious or inappropriate sexuality in the original parent scale indicated limited clinical Revised Conners' Parent Rating Scale usefulness and low item endorsement. However, this highlights the problem of scales based upon frequency of endorsement. Though some items rarely occur (e.g., items relating to psychosis), when they do occur they are important. The tradeoff of having a shorter scale with better user-compliance and acceptance, versus a longer scale covering many items that are important but rare, was decided in favor of brevity and focus in the current revision. In summary, the CPRS-R provides a reliable, accurate, and relatively brief measure of parental perceptions of children's disruptive behavior. Parent rating scales, such as the CPRS-R, are extremely relevant for both clinical and research purposes. They provide the opportunity to measure the most common behavior problems, they are inexpensive to administer, they have normative data for assessing deviance, and they allow people who are integral to the child's life, namely parents, to express their opinions about the target child. There is little reason not to include a parental checklist as an adjunctive measure to any clinical assessment. Further, parental checklists such as the CPRS-R provide a useful measure for monitoring children's behavior over time, especially during the course of a clinical or medical intervention. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant #MH01229 (C. Keith Conners, principal investigator). REFERENCES Achenbach, T. M.( & Edelbrock, C. (1981). Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four to sixteen. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 46 (1, Serial No. 188). Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1983). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. Achenbach, T. M., Hensley, V. R., Phares, V., & Grayson, D. (1990). Problems and competencies reported by parents of Australian and American children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 265-286. Achenbach, T. M., Howell, C. T., Quay, H. C., & Conners, C. K. (1991). National survey of problems and competencies among four- to sixteen-year-olds: Parents' reports for normative and clinical samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 56 (3), (Serial No. 37-976X) 1-131. American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. 267 American Psychological Association. Standards for educational and psychological testing (1985). Washington, DC: Author. Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1984). The effect of sampling error on convergence, improper solutions, and goodness-of-fit indices for maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis. Psychometrika, 49, 155-173. Anderson, J. C., Williams, S., McGee, R., & Silva, P. A. (1987). DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children: Prevalence in a large sample from the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 69-76. Arnold, L. E., Barnebey, N. S., & Smeltzer, D. J. (1981). First grade norms, factor analysis and cross correlation for Conners, Davids, and Quay-Peterson behavior rating scales. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 14, 269-275. Barkley, R. A. (1990). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press. Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238-246. Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software. Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606. Blouin, A. G., Conners, C. K., Seidel, W. T., & Blouin, J. (1989). The independence of hyperactivity from conduct disorder: Methodological considerations. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 34, 279-282. Campbell, S. B., & Steinert, Y. (1978). Comparisons of rating scales of child psychopathology in clinic and nonclinic samples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 358359. Cattell, R. B. (1978). The scientific use of factor analysis in behavioral and life sciences. New York: Plenum Press. Cohen, M., DuRant, R. H., & Cook, C. (1988). The Conners Teacher Rating Scale: Effects of age, sex, and race with special education children. Psychology in the Schools, 25, 195-202. Cohen, M., & Hynd, G. W. (1986). The Conners Teacher Rating Scale: A different factor structure with special education children. Psychology in the Schools, 23, 13-23. Cole, D. A. (1987). Utility of confirmatory factor analysis in test validation research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 584-594. Conners, C. (1970). Symptom patterns in hyperkinetic, neurotic, and normal children. Child Development, 41, 667-682. Conners, C. K. (1973). Rating scales for use in drug studies with children. Psychopharmacology Bulletin [Special issue on children]. 24-42. Conners, C. K. (1989). Manual for Conners' Rating Scales. N. Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. Conners, C. K. (1994). The Conners Rating Scales: Use in clinical assessment, treatment planning and research. In M. Maruish (Ed.), Use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum. Conners, C. K., Sitarenios, G., Parker, J. D. A., & Epstein, J. N. (1998). Revision and restandardization of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale: Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26 (this issue). Costello, E. J., Costello, A. J., Edelbrock, C., Burns, B. J., Dulcan, M. K., Brent, D., & Janiszewski, S. (1985). DSM-III disorders in pediatric primary care: Prevalence and risk factors. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45, 1107-1116. Everett, J. E. (1983). Factor comparability as a means of determining the number of factors and their rotation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 18, 197-218. Fischer, M., & Newby, R. F. (1991). Assessment of stimulant response in ADHD children using a refined multimethod clini- 268 cal protocol [Special issue on child psychopharmacology]. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 20, 232-244. Glow, R. A., Glow, P. H., & Rump, E. E. (1982). The stability of child behavior disorders: A one year test-retest study of Adelaide versions of the Conners Teacher and Parent Rating Scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 10, 33-59. Goyette, C. H., Conners, C. K., & Ulrich, R. F. (1978). Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6, 221-236. Hinshaw, S. P. (1991). Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 1-29. Horn, W. F., lalongo, N., Popovich, S., & Peradotto, D. (1987). Behavioral parent training and cognitive-behavioral selfcontrol therapy with ADD-H children: Comparative and combined effects. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 16, 57-68. Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (1986). LISREL VI: Analysis of linear structural relationships by maximum likelihood, instrumental variables, and least squares methods. Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software. Kessel, J. B., & Zimmerman, M. (1993). Reporting errors in studies of the diagnostic performance of self-administered questionnaires: Extent of the problem, recommendations for standardized presentation of results, and implications for the peer review process. Psychological Assessment, 5, 395-399. Kuehne, C., Kehle, T. J., & McMahon, W. (1987). Differences between children with attention deficit disorder, children with specific learning disabilities, and normal children. Journal of School Psychology, 25, 161-166. Landau, S., & Moore, L. A. (1991). Social skill deficits in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Review, 20, 235-251. Leon, G. R., Kendall, P. C., & Garber, J. (1980). Depression in children: Parent, teacher, and child perspectives. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 8, 221-235. March, J. S., Leonard, H. L., & Swedo, S. (1995). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. In J. S. March (Ed.), Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press. Conners, Sitarenios, Parker and Epstein Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R., & McDonald, R. P. (1988). Goodnessof-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 391-410. Mash, E. J., & Johnston, C. (1983). Parental perceptions of child behavior problems, parenting self-esteem, and mothers' reported stress in younger and older hyperactive and normal children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 6899. O'Connor, M., Foch, T., Sherry, T., & Plomin, R. (1980). A twin study of specific behavioral problems of socialization as viewed by parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 8, 189-199. Offord, D. R., Boyle, M. H., Szatmari, P., Rae-Grant, N. I., Links, P. S., Cadman, D. T., Byles, J. A., Crawford, J. W., Blum, H. M., & Byrne, C. (1987). Ontario Child Health Study. II. Sixmonth prevalence of disorder and rates of service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 832-836. Prior, M. L., & Wood, G. (1983). A comparison study of preschool children diagnosed as hyperactive. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 8, 191-207. Quay, H. C. (1983). A dimensional approach to behavior disorder: The Revised Behavior Problem Checklist. School Psychology Review, 12, 244-249. Ross, D. M., & Ross, S. A. (1976). Hyperactivity: Research, theory, and action. New York: Wiley. Ross, D. M., & Ross, S. A. (1982). Hyperactivity: Current issues, research, and theory (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. Tanaka, J. S., & Huba, G. J. (1984). Confirmatory hierarchical factor analysis of psychological distress measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 621-635. Velez, C. N., Johnson, J., & Cohen, P. (1989). A longitudinal analysis of selected risk factors for childhood psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 861-864. Werry, J. S., Sprague, R. L., & Cohen, N. M. (1975). Conners' Teacher Rating Scale for use in drug studies with children— An empirical study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 3, 217-229.