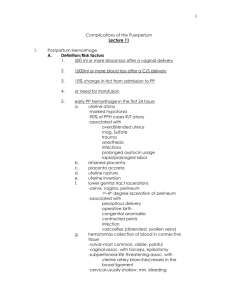

POSTPARTUM The postpartal period, or puerperium (from the Latin puer, for “child,” and parere, for “to bring forth”), refers to the 6-week period after childbirth. It is a time of maternal changes that are both retrogressive (involution of the uterus and vagina) and progressive (production of milk for lactation, restoration of the normal menstrual cycle, and beginning of a parenting role). Assessment During the puerperium, assessment of a woman is accomplished by health interview, physical examination, and analysis of laboratory data. It is important to ensure that physical changes, such as uterine involution, are occurring by evaluating uterine size and consistency and lochia flow amount. PHYSIOLOGICAL CHANGES OF THE POSPARTAL PERIOD Reproductive System Changes Involution is the process whereby the reproductive organs return to their nonpregnant state. By the time involution is complete (6 weeks), the uterus is completely return to its prepregnancy state. The Uterus Because uterine contraction begins immediately after placental delivery, the fundus of the uterus may be palpated through the abdominal wall, halfway between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis, within a few minutes after birth. One hour later, it will have risen to the level of the umbilicus, where it remains for approximately the next 24 hours. From then on, it decreases one fingerbreadth per day—on the first postpartal day, and so forth. By the ninth or tenth day, the uterus will no longer be detected by abdominal palpation. Lochia Uterine flow, consisting of blood, fragments of decidua, white blood cells, mucus, and some bacteria, is known as lochia. It takes approximately 6 weeks (the entire postpartal period). For the first 3 days after birth, a lochia discharge consists almost entirely of blood, with only small particles of decidua and mucus. Because of its mainly red color, it is termed lochia rubra. As the amount of blood involved in the cast-off tissue decreases (about the fourth day) and leukocytes begin to invade the area, as they do with any healing surface, the flow becomes pink or brownish (lochia serosa). On about the 10th day, the amount of the flow decreases and becomes colorless or white (lochia alba). Lochia alba is present in most women until the third week after birth, although it is not unusual for a lochia flow to last the entire 6 weeks of the puerperium. Saturating a perineal pad in less than 1 hour is considered an abnormally heavy flow and should be reported. Lochia should contain no large clots. Clots may indicate that a portion of the placenta has been retained and is preventing closure of the maternal uterine blood sinuses. Lochia should not have an offensive odor. Lochia has the same odor as menstrual blood. An offensive odor usually indicates that the uterus has become infected. The Cervix Contraction of the cervix toward its prepregnant state begins at once. By the end of 7 days, the external os has narrowed to the size of a pencil opening; the cervix feels firm and nongravid again. The Vagina After a vaginal birth, the vagina is soft, with few rugae, and its diameter is considerably greater than normal. The hymen is permanently torn and heals with small, separate tags of tissue. It takes the entire postpartal period for the vagina to involute (by contraction, as with the uterus) until it gradually returns to its approximate prepregnancy state. The Perineum Because of the great amount of pressure experienced during birth, the perineum feels edematous and tender immediately after birth. . The labia majora and labia minora typically remain atrophic and softened after birth, never returning to their prepregnancy state. BREAST In many women, breast distention becomes marked, and this often is accompanied by a feeling of heat or pain. The distention is not limited to the milk ducts but occurs in the surrounding tissue as well, because blood and lymph enter the area to contribute fluid to the formation of milk. This feeling of tension in the breasts on the third or fourth day after birth is termed primary engorgement. It fades as the infant begins effective sucking termed primary engorgement. It fades as the infant begins effective sucking and empties the breasts of milk. Systemic Changes Pregnancy hormones begin to decrease as soon as the placenta is no longer present. Levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and human placental lactogen (hPL) are almost negligible by 24 hours. By week 1, progestin, estrone, and estradiol are all at prepregnancy levels. Estrol may be elevated for an additional week before it reaches prepregnancy levels. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) remains low for about 12 days and then begins to rise as a new menstrual cycle is initiated. Urinary System During pregnancy, as much as 2000 to 3000 mL excess fluid accumulates in the body. An extensive diuresis begins to take place almost immediately after birth to rid the body of this fluid. This easily increases the daily output of a postpartal woman from a normal level of 1500 mL to as much as 3000 mL/day during the second to fifth day after birth. This marked increase in urine production causes the bladder to fill rapidly. During a vaginal birth, the fetal head exerts a great deal of pressure on the bladder and urethra as it passes on the bladder’s underside. This pressure may leave the bladder with a transient loss of tone that, together with the edema surrounding the urethra, decreases a woman’s ability to sense when she has to void. Urinary System To prevent permanent damage to the bladder from overdistention, assess a woman’s abdomen frequently in the immediate postpartal period. On palpation, a full bladder is felt as a hard or firm area just above the symphysis pubis. On percussion (placing one finger flat on the woman’s abdomen over the bladder and tapping it with the middle finger of the other hand), a full bladder sounds resonant, in contrast to the dull, thudding sound of non–fluid-filled tissue. Circulatory System The diuresis that is evident between the second and fifth days after birth, as well as the blood loss at birth, acts to reduce the added blood volume a woman accumulated during pregnancy. This reduction occurs so rapidly, in fact, that the blood volume returns to its normal prepregnancy level by the first or second week after birth. The usual blood loss with a vaginal birth is 300 to 500 mL. With a cesarean birth, it is 500 to 1000 mL. A 4-point decrease in hematocrit (proportion of red blood cells to circulating plasma) and a 1-g decrease in hemoglobin value occur with each 250 mL of blood lost. Women usually continue to have the same high level of plasma fibrinogen during the first postpartal weeks as they did during pregnancy. This is a protective measure against hemorrhage. However, this high level also increases the risk of thrombus formation. Gastrointestinal System Digestion and absorption begin to be active again soon after birth unless a woman has had a cesarean birth. Almost immediately, the woman feels hungry and thirsty and she can eat without difficulty from nausea or vomiting during this time. Hemorrhoids (distended rectal veins) that have been pushed out of the rectum because of the effort of pelvicstage pushing often are present. Bowel sounds are active, but passage of stool through the bowel may be slow because of the still-present effect of relaxin on the bowel. Bowel evacuation may be difficult because of the pain of episiotomy sutures or hemorrhoids. Integumentary System After birth, the stretch marks on a woman’s abdomen (striae gravidarum) still appear reddened and may be even more prominent than during pregnancy, when they were tightly stretched. Excessive pigment on the face and neck (chloasma) and on the abdomen (linea nigra) will become barely detectable in 6 weeks’ time. If diastasis recti (overstretching and separation of the abdominal musculature) is present, the area will appear slightly indented. If the separation is large, it will appear as a bluish area in the abdominal midline. Modified situps help to strengthen abdominal muscles and return abdominal support to its prepregnant level Vital Sign Changes Temperature A woman may show a slight increase in temperature during the first 24 hours after birth because of dehydration that occurred during labor. If she receives adequate fluid during the first 24 hours, this temperature elevation will return to normal. Any woman whose oral temperature rises above 100.4° F (38° C), excluding the first 24-hour period, is considered by criteria of the Joint Commission on Maternal Welfare to be febrile. In such women, a postpartal infection may be present. Occasionally, when a woman’s breasts fill with milk on the third or fourth postpartum day, her temperature rises for a period of hours because of the increased vascular activity involved. If the elevation in temperature lasts longer than a few hours, however, infection is a more likely reason. Vital Sign Changes Pulse A woman’s pulse rate during the postpartal period is usually slightly slower than normal. During pregnancy, the distended uterus obstructed the amount of venous blood returning to the heart; after birth, to accommodate the increased blood volume returning to the heart, stroke volume increases. This increased stroke volume reduces the pulse rate to between 60 and 70 beats per minute. Vital Sign Changes Blood Pressure Blood pressure should also be monitored carefully during the postpartal period, because a decrease in this can indicate bleeding. In contrast, an elevation above 140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic may indicate the development of postpartal pregnancy-induced hypertension, an unusual but serious complication of the puerperium. To evaluate blood pressure, compare a woman’s pressure with her prepregnancy level if possible, rather than with standard blood pressure ranges. Oxytocics, drugs frequently administered during the postpartal period to achieve uterine contraction, cause contraction of all smooth muscle, including blood vessels that can increase blood pressure. Progressive Changes Two physiologic changes that occur during the puerperium involve progressive changes, or the building of new tissue. Because building new tissue requires good nutrition, caution women against strict dieting that would limit cell-building ability during the first 6 weeks after childbirth. Lactation The formation of breast milk (lactation) begins in a postpartal woman whether or not she plans to breastfeed. For the first 2 days after birth, an average woman notices little change in her breasts from the way they were during pregnancy. Since midway through pregnancy, she has been secreting colostrum, a thin, watery, prelactation secretion. She continues to excrete this fluid the first 2 postpartum days. On the third day, her breasts become full and feel tense or tender as milk forms within breast ducts. Lactation Breast milk forms in response to the decrease in estrogen and progesterone levels that follows delivery of the placenta (which stimulates prolactin production and, consequently, milk production). When breast milk first begins to form, the milk ducts become distended. The distention of the breast is not limited to the milk ducts but occurs in the surrounding tissue as well, because blood and lymph enter the area to contribute fluid to the formation of milk. This feeling of tension in the breasts on the third or fourth day after birth is termed primary engorgement. It fades as the infant begins effective sucking and empties the breasts of milk. Return of Menstrual Flow With the delivery of the placenta, the production of placental estrogen and progesterone ends. The resulting decrease in hormone concentrations causes a rise in production of FSH by the pituitary, which leads, with only a slight delay, to the return of ovulation. This initiates the return of normal menstrual cycles. A woman who is not breastfeeding can expect her menstrual flow to return in 6 to 10 weeks after birth. If she is breastfeeding, a menstrual flow may not return for 3 or 4 months (lactational amenorrhea) or, in some women, for the entire lactation period. However, the absence of a menstrual flow does not guarantee that a woman will not conceive during this time, because she may ovulate well before menstruation returns NURSING RESPONSIBILITIES a. Perineal Care - inspect the perineum. Observe for ecchymosis, hematoma, erythema, edema, intactness, and presence of drainage or bleeding from any episiotomy stitches. b. Provide Pain Relief for Afterpains - Pain from uterine contractions can be intense, but you can assure a woman that this type of discomfort is normal and rarely lasts longer than 3 days. c. Relieve Muscular Aches - Many women feel sore and aching after labor and birth because of the excessive energy they used for pushing during the pelvic division of labor. A backrub is effective for relieving an aching back or shoulders. d. Administer Cold and Hot Therapy - Applying an ice or cold pack to the perineum during the first 24 hours reduces perineal edema and the possibility of hematoma formation, thereby reducing pain and promoting healing and comfort. After the first 24 hours healing increases best if circulation to the area by the use of heat. Dry heat in the form of a perineal hot pack or moist heat with a sitz bath. e. Episiotomy Care - the perineal area heals rapidly, you can assure a woman that this discomfort is normal and does not usually last longer than 5 or 6 days. Many physicians and nursemidwives order a soothing cream or anesthetic spray to be applied to the suture line to reduce discomfort. f. Inspect Lochia - Check the Consistency: Lochia should contain no large clots. Clots may indicate that a portion of the placenta has been retained and is preventing closure of the maternal uterine blood sinuses. In any event, large clots denote poor uterine contraction, which needs to be corrected. Observe the Pattern: Lochia is red for the first 1 to 3 days (lochia rubra), pinkish-brown from days 4 to 10 (lochia serosa), and then white (lochia alba) for as long as 6 weeks after birth. The pattern of lochia (rubra to serosa to alba) should not reverse. PSYCHOLOGICAL CHNGES Postpartal Blues During the postpartal period, as many as 50% of women experience some feelings of overwhelming sadness (Buultjens & Liamputtong, 2007). They may burst into tears easily or feel let down or irritable. This temporary feeling after birth has long been known as the “baby blues.” This phenomenon may be caused by hormonal changes, particularly the decrease in estrogen and progesterone that occurs with delivery of the placenta. For some women, it may be a response to dependence and low selfesteem caused by exhaustion, being away from home, physical discomfort, and the tension engendered by assuming a new role, especially if a woman is not receiving support from her partner. PSYCHOLOGICAL CHNGES The syndrome is evidenced by tearfulness, feelings of inadequacy, mood lability, anorexia, and sleep disturbance. Anticipatory guidance and individualized support from health care personnel are important to help the parents understand that this response is normal. You can assure a woman that sudden crying episodes may occur; otherwise, she may have difficulty understanding what is happening to her. Her support person also needs assurance, or he can think the woman is unhappy with him or their new baby or is keeping some terrible secret about the baby from him. Phases of the Puerperium Reva Rubin, a nurse, divided the puerperium into three separate phases (Rubin, 1977). Taking-In Phase A time when the new parents review their pregnancy and the labor and birth, a time of reflection. During this 2- to 3-day period, a woman is largely passive. This dependence results partly from her physical discomfort because of afterpains; partly from her uncertainty in caring for her newborn; and partly from the extreme exhaustion that follows childbirth. Taking-Hold Phase After a time of passive dependence, a woman begins to initiate action. Now, she begins to take a strong interest. , it is always best to give a woman brief demonstrations of baby care and then allow her to care for her child herself— with watchful guidance. Letting-Go Phase In the third phase, called letting-go, a woman finally redefines her new role. She gives up the fantasized image of her child and accepts the real one; she gives up her old role of being childless or the mother of only one or two (or however many children she had before this birth).