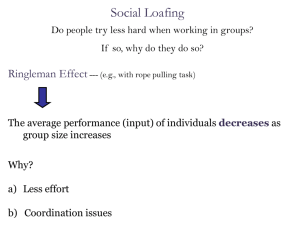

This article was downloaded by: [Umeå University Library] On: 13 November 2014, At: 12:58 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of Social Psychology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vsoc20 Gender and Social Loafing in Japan Naoki Kugihara a a Department of Humanities , Kyushu Institute of Technology Published online: 03 Apr 2010. To cite this article: Naoki Kugihara (1999) Gender and Social Loafing in Japan, The Journal of Social Psychology, 139:4, 516-526, DOI: 10.1080/00224549909598410 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224549909598410 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/ page/terms-and-conditions The Journal of Social Psychology, 1999,139(4),516-526 Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 Gender and Social Loafing in Japan NAOKI KUGIHARA Deparment of Humanities Kyushu Institute of Technology ABSTRACT. The author investigated gender differences in social loafing among 18 men and 18 women in Japan. The participants were divided into groups of 9 members. Ropes were connected to strongly built steel frames set near the ceiling of the laboratory. Each participant had to pull the rope as through arm wrestling. The participants engaged in 12 trials-2 individual trials and 10 group trials. In the group trials, the participants believed that only the group’s power, but not individual participants’power, was being gauged. The difference between the data from individual trials and the data from group trials was adopted as a measure of social loafing. The women tended to loaf less than the men, and the men’s effort suddenly declined when the situation was changed from an individual to a collective work setting. However, the women did not show that change. The author interpreted the findings from the viewpoint of gender difference in the quality of achievement motivation among Japanese participants. THE PERCENTAGE OF JAPANESE working women has risen steadily over the years. Women made up 31.1% of the total work force in 1960 and 38.9% in 1995. The figure is, however, well short of the 64.8% of women working in the United States (Women’s Bureau in Japan Ministry of Labor, 1996). In Japan, women occupy the majority of jobs in certain fields. For example, 94% of kindergarten teachers, 97% of nurses, and 62% of elementary school teachers are women. Also, before and after World War 11, women’s work on the assembly lines in the textile and home electric industries helped to drive the Japanese economy. The many fields where men traditionally dominate, on the other hand, include the Self Defense Force, the police, and so forth. If a gender difference exists in social loafing, it would considerably affect social productivity as a whole. Social loafing refers to a phenomenon that shows that the amount of work performed per person in a group tends to be smaller than that performed by an The author would like to thank R. Long and G. Russell for help in the refinement of English expression. Address correspondence to Naoki Kugihara, Department of Humanities, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Kitakyushu 804,Japan. 516 Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 Kugihara 517 individual alone (Latane, Williams, & Harkins, 1979). The amount of individual motivation and effort declines in collective tasks in comparison with that in individual or coactive tasks (Karau & Williams, 1993). In collective work, the members of a group work together with actual or imaginary others, but effort, money, and time (input) invested by each member are all pooled in the group, thus making each member’s input unidentifiable. A typical example is an additive task such as a tug of war. In contrast, a coactive task is work in which a member’s input is not pooled in the group and remains identifiable. It remains unclear whether there is a gender difference in social loafing, because little research has been conducted either in Japan or in Western countries. However, it is possible to predict, though indirectly, the existence of gender differences in social loafing from studies of gender differences and results of experimental research on gender differences in other fields. Though opinion is divided on which characteristics of conformity and cooperation apply particularly to women, substantial research conducted in the West has indicated that women have such characteristics to a great degree (Crutchfield, 1955; McGuire, 1985). In addition, women are likely to be expected to perform such female roles as maintaining friendly relations with others and keeping group harmony. Contrary to this, men are expected to perform poweroriented roles such as exerting influence on and control over others (Eagly, 1987). Furthermore, it is clear that Western men generally score high in compet- itiveness and often act accordingly, whereas women score high in cooperation (Knight & Dubro, 1984). AIso, women in Western countries are considered gen- erally more oriented to maintaining group coordination and human relationsthat is, toward consideration-whereas men are more oriented toward achievement (Anderson & Blanchard, 1982). From the results of such research, it may be assumed that in the West, women tend to put more value on collective tasks than men do, thus showing high performance in such tasks (Karau & Williams, 1993). In Japan, it is assumed that it is rather difficult to find gender differences in social loafing. Although some researchers have pointed out that Japanese women as well as Westem women have orientations of conformity and cooperation (Kashima et al., 1995; Mamiya, 1979), other research has suggested that not only women but also men in Asian countries, including Japan, have such orientations (Triandis, 1989; Wheeler, Reis, & Bond, 1989). An experiment in social loafing conducted at a U.S. university with Chinese graduate students as participants showed clearly that their performance in a collective task increased over that in an individual task. This experiment revealed social effort rather than social loafing (Gabrenya, Wang, & Latane, 1985). On the other hand, an experiment with elementary and junior high school pupils in Taiwan showed the existence of social loafing (Gabrenya, Latane, & Wang, 1983). As for research involving Japanese people, there are inconsistent findings, some that showed the existence of social loafing (Kawana, Williams, & Latane, Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 5 18 The Journal of Social Psychology 1982; Kokubo, 1994) and others that did not show the existence of social loafing (Yamaguchi, Okamoto, & Oka, 1985). An experiment (Shirakashi, 1991) with Japanese university students as participants showed neither social effon nor social loding. Shirakashi made the following analysis of his findings that Chinese students studying in the United States showed social effort, whereas their Japanese counterpartsshowed neither social effort nor social loafing: Would such findings have possibly resulted from the conditions wherein Chinese students studying in the United States, far from their country, were strongly drawn to their traditional group-oriented precepts in the surroundings of a foreign culture and, therefore, showed the characteristics of group orientation more distinctively than they did when they were in their homeland? In contrast, did young Japanese students reveal their position somewhere between the individual orientation of Westerners and the strong group orientation of Asians in the United States? As Shirakashi (1991) pointed out, although Japanese people are more individually oriented than other Asian people, the tendency toward group orientation is stronger in Japan than in the West. If that is true and if the degree that culture influences social loafing is salient, the effects of gender differences would be masked, making detection more difficult. Other research showed that gender differences in Japanese people were not so distinct as those among people in the United States. Kashiwagi and Azuma (1981) pointed out that gender differences are more inherent in the United States than in Japan and that the gender socialization process in children is differentiated. The results of Kashiwagi and Azuma’s research suggest that gender difference in social loafing does not appear among Japanese people. Method Participants The participants were 18 female students (mean age = 19.0 years, SD = 1S ) and 18 male students (mean age = 19.9 years, SD = 2.2) recruited in 1994 from undergraduate classes in psychology and educational psychology. There were four experimental groups, each composed of 9 members. Apparatus Improvements were made on the apparatus originally developed by Ingham, Levinger, Graves, and Peckham (1974). It was designed so that arm power (when engaged in arm wrestling) could be measured simultaneously and individually for each of the 9 members. A strongly built rigid H-steel frame was constructed on the ceiling of the laboratory. In the laboratory were placed nine booths with desks. Ropes were hanging vertically from the H-steel frame to the desks. A grip like a train strap was attached to the end of each rope. The strap was 20 cm above Kugihara 519 the desk. Between the H-steel frame and the upper end of the rope, a load cell Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 was installed that could transform an individual participant’s strain into electric signals and transmit them to the strain gauge (produced by Tokyo Sokki Research Institute, digital type kinetic strain gauge DRA- IOA). The strain gauge scanned each load cell every 1/10 s and stored the data in a computer (NEC PC9801 DA)-that is, the change of an individual participant’s power could be measured every 1/10 s. Procedure The following instructions were given to the 9 participants after they were seated at the designated desks: This experiment is designed to test collective task performance. We measure the group’s power as a whole when several members exert their power simultaneously. The purpose is not to measure how much power each member can exert but to measure the total performance of the group as a whole. It will help if you imagine you are engaged in a tug of war, You will be asked to pull on a strap hanging in front of you as hard as you possibly can as though you were engaged in arm wrestling. You are requested to put your elbow on the desk properly and pull with your dominant hand. Only one unit of data is stored in the computer as a pulling power of all the 9 members of the group. However, each participant’s power was actually measured separately. After the initial instructions, I asked several participants to pull simultaneously and showed the data on the computer display to all of them, that is, only the data indicating a changing output of the group. There were 12 trials in all. The participants were informed that at the 1st and the 12th trials, each participant’s power would be measured (individual trial) and that at the other trials, the group’s power would be measured (group trial). At the individual trials, the participants took turns in pulling according to seat number. As mentioned earlier, this apparatus can measure 9 participants’ individual power separately at the same time, but we measured the participants’ power 1 by 1 at the individual trials so that they would not suspect that individual power could be measured while they were engaged in group trials. Each trial lasted 6 s. The participants were asked to pull on a rope for 6 s to the full extent of their ability. There was a 3-min break between the trials. The following instructions were given to explain the procedures of tug of War: I . “Set!” During this phase, you will secure a grip on the strap and get ready with your elbow on the desk. 2. “Pull!” During this phase, you are required to pull as hard as you can for a period of 6 s. While pulling, do not jerk on the rope by “accelerating” your power, but keep on pulling for 6 s without taking your elbow off the desk. 520 The Journal of Social Psychology 3. “Stop!” We will give you a sign of “Stop!” after 6 s. At this sign, you will stop pulling and take your hand off the grip. Then you may rest for a while, and then the next trial will start. The following instructions were also given: The experimenter will measure each participant’s performance before the real experiment starts. Since this apparatus can measure only one instance of power at a time, Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 you are asked to take turns and pull alone. Then the first participant will pull first. The other participants must not touch the straps. Following these procedures, 9 participants performed individual trials 1 by 1. Then after a 3-min break, the group trials were done 10 times. Before the group trials, it was again emphasized that the experimental apparatus was measuring only the total power produced by the group. After the 10 group trials, individual trials were conducted for the second time. The participants then filled in questionnaires, which contained the following three items ranked on 5-point scales: (a) how hard participants themselves had exerted their power (individual output), (b) how hard participants believed that other members had exerted their power (others’ output), and (c) how much participants thought they had contributed to the group (group contribution). Finally, the participants were debriefed. Results Participants Evaluations of Their Pe~ormanceon the Experimental Tasks The 5-point scale scores for individual output-men: M = 4.61, SD = .76; women: M = 4.39,SD = .49-showed no significant differences between the sexes, r(34) = 1.02, ns. Both men and women had subjective cognizance of the fact that they pulled at nearly 100% of their ability. Both the scores of others’ out- put, t(34) = 1.55, ns, and the scores of group contribution, t(34) = 0.00, ns, showed no significant differences between the sexes. Analysis of Strain I obtained 10 measurements per s for each participant. Because the duration of one trial was 6 s, I obtained 60 measurements for each participant for each trial. Because the participant’s strain was unstable immediately after the start, I adopted the measurements that were recorded after 2 s from the start as valid data. I calculated the mean of 40 measurements for each participant at every trial. There was a distinct gender difference in strain. From the two individual trials, the scores for men, M = 22.03 kg, SD = 4.73, were more than two times higher than the scores for women, M = 10.55 kg, SD = 3.87. The mean scores from 10 Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 Kugihara 521 group trials declined for both genders: for men, M = 17.89 kg, SD = 3.82; for women, M = 9.63 kg, SD = 3.54. However, there were differences in scores+. 14 kg and 0.92 kg for men and women, respectively-between individual trials and group trials. If the index of social loafing can be presented as the difference in scores between individual trials and group trials, the data from the present research showed that the extent of social loafing was greater for men than for women. However, the rather high correlation between the scores of individual trials and the index of social loafing-n = .64and .42 for men and women, respectively-could be an indication that persons of both genders with high resources tended to engage in social loafing. On the other hand, these data may indicate merely that persons with high resources showed a wide range of variations in output at each trial or that they had enough surplus energy to allow such variations. Because variables from individual resources cannot be separated from variables of gender difference, one cannot conclude from the raw data that the greater extent of social loafing among men was attributable to men’s greater strength in pulling. To negate such variables of individual resources, I calculated the means and standard deviations of the scores of 12 trials, both individual and group, for each participant; from these, I calculated standard scores for each participant. Therefore, even if participants obtained the same scores, their standard scores would vary by individual. Figure 1 contains the change in standard scores of strain for each trial. 1.5 - -e- 1.0- E 3 3 e m 3 0.5 Men Women - 0.0- .-c x -0.5 E - 1 -1.0’. - I f 1 Individual trial 2 r I 3 I 4 I 5 * I 6 7 Group trials 8 9 -1 - # t - 0 Individual trial FIGURE 1. Variation of strain: standard scores based on means and standard deviations (per individual) for 12 trials. Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 522 The Journal of Social Psychology I analyzed the difference between the mean of the 2 individual trials at the beginning and at the end and the mean of the 10 group trials as an index of social loafing, which showed a tendency toward gender difference, t(34) = 1.88, p < .1. Furthermore, it was clarified that there existed gender differences in social loafing in the 1st group trial, t(34) = 2. 61, p < .01, and the 10th group trial, f(34) = 2.49, p < .05. No other significant difference was found. From the aforementioned data, the existence of gender differences in social loafing was clear. Furthermore, the men engaged in social loafing immediately after beginning the collective tasks, whereas the women did not show such change. The women were not much influenced by changes of trial setting (e.g., individual vs. group trials); they showed a gradual decline in strain, followed by a gradual increase as trials proceeded, which could be interpreted as corresponding to a typical work curve. Discussion In the present research involving Japanese participants, the women engaged in social loafing less than the men did. The results refute the hypothesis that the Japanese collective orientation masks differences in gender and, thus, support the prediction of Karau and Williams (1993), who conjectured that women are generally oriented to maintenance of group coordination and human relations, whereas men tend to be oriented toward task achievement. As a result, women may view collective tasks as more important than individual tasks and, therefore, show higher performance in the former. For this reason, Karau and Williams predicted that women do not engage in social loafing. However, when I analyzed the results of my research, the interpretations of Karau and Williams (1993) required modification. According to the results of the questionnaire, both men and women perceived subjectively that they pulled at nearly full power during the collective condition; however, the men’s actual pull strength suddenly declined after they started the collective tasks. On the other hand, the women did not show such a tendency during the collective condition. In the background of such gender differences in response patterns, gender differences seem to exist in achievement motivation rather than in gender orientation. Tachibana and Koyasu (1978) conducted research into the relationship between achievement motivation and anagram tasks, with Japanese junior high school pupils as participants. The boys with strong achievement motivation showed higher task-solving ability under conditions in which hard exertion was emphasized (they were told that one phase of intelligence was being measured) than under conditions in which high achievement was not required and relaxation was allowed (they were told that standard data, such as the mean value, were being measured). In contrast, girls with strong achievement motivation showed poorer task-solving ability under conditions that required high achievement than under relaxed conditions. The boys tackled tasks seriously only when instruc- Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 Kugihara 523 tions induced them to achieve, whereas the girls worked earnestly on tasks, irrespective of instructions, and went beyond the level of optimal motivation in a group with achievement conditions and high motivation for achievement. Thus, their performance declined. The girls had a tendency to work to the full extent of their ability, even in relaxed conditions; as a result, when girls with high achievement motivation were asked to achieve a higher goal, the outcome was adverse. In the United States, McClelland, Atkinson, Clark, and Lowell (1953) also reported that female participants showed higher achievement scores than male participants did under neutral conditions; however, female participants’ scores did not increase as male participants’ scores did when the instructions encourage achievement. In the present research, the results of the questionnaire showed clearly that both the men and the women perceived subjectively that they pulled on the rope at nearly full power. That perception showed a high overall achievement motivation toward the tasks. Therefore, it can be said that men with high achievement motivation increase their performance if they are placed in a solitary condition in which they are made conscious of high performance. However, during group trials in which individual effort cannot be monitored, men may not exert their full capabilities. Unlike men, women with high achievement motivation have a tendency to work hard in whatever conditions they are subjected to; therefore, there was not much difference in women’s scores between individual trials and group trials as there was in the case of the men. Further research is needed to understand the influence of gender, culture, and achievement motivation on social loafing. Second, it is necessary to verify whether the present results are universally true across various types of tasks. Most social psychology textbooks that discuss sex differences in influenceability suggest that women are more susceptible to sympathy and persuasion than men are (e.g., Allen, 1965;Aronson, 1972; Baker, 1975; Baron, Byme, & Griffitt, 1974; Bass, 1961; Bird, 1940; Freedman, Carlsmith, & Sears, 1970; Krech, Crutchfield, & Ballachey, 1962; Middlebrook, 1974; Secord & Backman, 1964; Worchell & Cooper, 1976). On the other hand, some criticism points out that women are not familiar with, or cognizant of, tasks and topics used in such experiments fe.g., Baron & Byme, 1977; Jones, Hendrick, & Epstein, 1979; Sistrunk & McDavid, 1971). In addition, some researchers have pointed out that if tasks are designed so that men are unfamiliar with them, men are more affected by such tasks (Eagly & Carli, 1981; Sistrunk & McDavid, 1971).Therefore, it may be speculated that women would show a tendency to engage in social loafing if researchers gave them different kinds of tasks. Physical strength, required in the present experiment, is expected of men. Consequently, if women exerted superior physical power, it would not add much to the experimenter’s evaluation of them. Kashiwagi (1972), on the basis of factor analysis, picked out the factors of intelligence and action for the male role and the factors of beauty and obedience for the female role. In her analysis, action Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 524 The Journal of Social Psychology included such items as economic power, strong will, activity, positive attitude, devotion to work,and patience. Power is generally expected of men. In addition, some research has pointed out that variables such as ability, competition, and achievement are not in accord with the concept of femininity, that women’s success is incompatible with femininity, and that women, therefore, fear success (Homer, 1972). According to this interpretation, women were already engaging in social loafing during the individual tasks so that the experimenters and others would not give them negative evaluations, as mentioned earlier. Or it may be possible that women engage in social loafing less than men but engage in individual loafing more than men. Third, the effects of the ratio of mixture-the proportion of men and women in a group-on individual performance in collective tasks deserve further investigation. It is commonly said that when 10 people are carrying a portable shrine (Omikoshi) at a Japanese festival, 2 are seriously supporting the weight of the shrine, 2 are hanging from the shrine (carried by others), and the remaining 6 are just giving the impression of carrying. The results of my research showed that social loafing was indicated by the differences of scores between the individual trials and the group trials (a mean of the 1st trial and the 10th trial), that 2 men and 5 women obtained minus or zero scores for social loafing, and that 2 men and 6 women pulled 1 kg or less. The latter finding indicates that about 20% of the men and 60% of the women pulled seriously. More research is needed to explore the effect of gender on the distribution of social loafing in individual performances. REFERENCES Allen, V.L. (1965). Situational factors in conformity. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2). New York: Academic Press. Anderson, L. R., & Blanchard, P. N. (1982). Sex differences in task and social-emotional behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 3, 109-1 39. Aronson, E. (1972). The social animal. San Francisco: Freeman. Baker, T. (1975). Sex differences in social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), A survey of social psychology. Hinsdale, IL: Dryden Press. Baron, R. A., & Byrne, D. (1977).Social psychology: Understanding human interaction. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Baron, R. A., Byme, D., & Griffitt, W. (1974). Social psychology: Understanding human interaction. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Bass, B. M. (1961). Conformity, deviation, and a general theory of interpersonal behavior. In B. A. Berg & B. M. Bass (Eds.), Conformifyand deviation. New York: Harper. Bird, C. (1940). Social psychology. New York: Appleton. Crutchfield, R. A. (1955). Conformity and character. American Psychologist, 10, 191-198. Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex diflerences in social behavior: A social-role inferpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. (1981). Sex of researchers and sex-typed communications as determinants of sex differences in influenceability. A meta-analysis of social influence studies. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 1-20. Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 Kugihara 525 Freedman, J. L., Carlsmith, J. M., & Sears, D. 0. (1970). Social psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Gabrenya, W., Jr., Latane, B., & Wang, Y. E. (1983). Social loafing in cross-cultural perspective: Chinese on Taiwan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 14, 368-384. Gabrenya, W., Jr., W a g , Y. E., & Latane, B. (1985). Social loafing on an optimizing task: Cross-cultural differences among Chinese and Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural PSyCholOgy, 14, 223-242. Homer, M . S . (1972). Toward an understanding of achievement-related conflicts in women. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 157-175. Ingham, A. G., Levinger, G., Graves, J., & Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelman effect: Studies of group size and group performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 371-384. Jones, R. A., Hendrick, D.,& Epstein, Y.M. (1979). Introduction to social psychology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D.(1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 68 1-706. Kashima, Y., Yamaguchi, S., Kim, U., Choi, S. D.,Gelfand, M., & Yuki, M. (1995). Culture, gender, and self A perspective from individualism-collectivism research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychoiogy, 69, 925-937. Kashiwagi, K. (1972).Cognition of sex role in adolescence (11). Japanese Journal of Educational Psyc/zo/ogy, 20,48-58. (in Japanese with English summary) Kashiwagi, K., & Azuma, H. (1981). Sex-typing in the cognitive socialization processes in Japan and the US.Japanese Journal of Psychology, 52, 296300. (in Japanese with English summary) Kawana, K., Williams, K., & Latane, B. (1982). The social loafing effect: The case of Japanese junior high school students. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Convention of the Japanese Psychological Association, 428. (in Japanese) Knight, G. P., & Dubro, A. F. (1984). Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic social values: An individualized regression and clustering approach. Journal of Personaliry and Social Psychology, 46, 98-105. Kokubo, T. (1994). An effect of incentive to task performance on social loafing. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Convention of the Japanese Group Dynamics Association, 88-89. (in Japanese) Krech, D., Crutchfield, R. S., & Ballachey, E. L. (1962). Individual in society: A textbook of social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill. Latane, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. G. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The cause and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 822-832. Mamiya, T. (1979). Psychology of sex diference. Tokyo: Kaneko Shobou. (in Japanese) McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. New York: Appleton. McGuire, W. J. (1985). Attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology: Vol. 2 (3rd ed., pp. 233-346). New York: Random House. Middlebrook, P. N. (1974). Social psychology and modern life. New York: Knopf. Secord, P. F. & Backman, C. W. (1964). Social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill. Shirakashi, S . (1991). Social loafing. In J. Misumi & T. Kinoshita (Eds.), The development of modern social psychology (2nd ed., pp. 125-158). Kyoto: Nakanishiya Shuppan. (in Japanese) Sistrunk, F., & McDavid, J. W. (1971). Sex variables in conforming behavior. Journal of Personalify and Social Psychology, 17, 200-207. Downloaded by [Umeå University Library] at 12:58 13 November 2014 526 The Journal of Social Psychology Tachibana, Y., & Koyasu, M. (1978). The relationship between achievement motive and anagram task solution. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 26, 252-256. (in Japanese with English summary) Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review, 96, 506-520. Wheeler, L., Reis, H. T., & Bond, M. H. (1989). Collectivism-individualism in everyday social life: The Middle Kingdom and the melting pot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 79-86. Women's Bureau in Japan Ministry of Labor. (1996). Annual report ofacruaf conditions of working women. Tokyo: Japan Institute of Workers' Evolution. (in Japanese) Worchel, S., Cooper, J. (1976). Undersfandingsocial psychology. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. Yamaguchi, S., Okamoto, K., & Oka, T. (1985). Effects of coactor's presence: Social loafing and social facilitation. Japanese Psychological Research, 27, 2 15-222. Received July 28, 1997 Accepted November 25, '1997