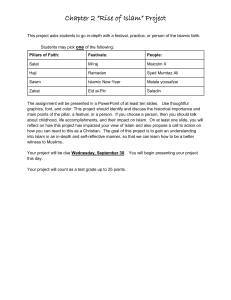

An IHR offprint, originally published in the journal Quranicsmos, Volume 1, Issue 1, August 2017 Conference Paper A Critical Analysis of Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri’s Perspective on Islam and Animal Experimentation1 Nadeem Haque nhaque@mail.com Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri Animal experimentation is taken for granted today, as a practice which is vital for the usufruct of human beings, irrespective of what ‘belief system’ one belongs to. Among these major world belief systems is Islam. Can animal experimentation be addressed in the Islamic ethical framework, especially since it was not practiced as an institution in the past? In 1984, the unique Islamic Scholar and activist Al Hafiz Basheer Ahmad Masri, presented a paper for the first time, on the Islamic approach to animal experimentation. But before we discuss his views, it would be instructive to review, very briefly, some aspects of Masri’s background and what led him to write about Animal Welfare in Islam and in particular, animal experimentation. Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri led a fascinating life, some of which has been recounted in a brief biography2. Masri was born in then British ruled India in 1914, and had migrated to England in the early 1960s, where he resided till his demise at the age of 78, in 1992. His father, scholar (Abdur Rahman) converted to Islam from Hinduism and went to study at Al-Azhar University Egypt. When Basheer was born, Abdur Rahman kept his promise and started to train the young Basheer on Islamic matters. At the age of seven Abdur Rahman made him (Basheer) memorize the entire Quran and by the age 13, he had memorized the entire Quran; hence, he was called “Al-Hafiz” (one who has committed the entire Quran to memory). In time, Basheer Ahmad Masri graduated with a B.A. (specializing in Arabic) from Government College Lahore – the most prestigious university in India at the time. Masri subsequently migrated to Africa and worked with SPCA in East Africa. He eventually became the principal of two secondary schools in then Tanganyika (in the cities of Arusha and Dar es Salaam). In 1935, he migrated to Uganda and subsequently helped established the Uganda People`s Congress with Milton Obote, who later on became the President of Uganda. In early 1960s, Masri studied Journalism in England (London) – obtaining a qualification in this field and became co-editor of the prestigious The Islamic Review journal, in the 1960s whilst at the same time being the full-time (Sunni) Imam of Shah Jahan (Woking Mosque), then the central mosque for the whole of Europe, in terms of influence. In 1968, he left his position at the mosque and toured over 40 countries with his wife in a car; this trip took three years. He attended 1 This was a paper presented by Nadeem Haque at the Ferrater Mora Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, the “Summer School 2015: The Ethics of Using Animal in Research”. 2 Nadeem Haque, “Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri: Muslim, Scholar, Activist – Rebel with a Just Cause”, ed. Lisa Kemmerer et al, Call to Compassion (New York: Lantern Books, 2011), 185-196. Al-Azhar University for one year, studying Arabic, to advance his knowledge of the language. In his lifetime, Masri gave over 200 lectures on Islam to wider public (aside from Friday sermons as Imam). Masri’s interest in the area of concern for animals evolved over the decades from concern primarily for the rights of human beings, to embrace the wider spectrum of sentience on this planet. He finally wrote his now classic book: Animals in Islam. His research led him to some questions and conclusions where he was led to believe that: “The basic and most important point to understand about using animals in science is that the same moral, ethical and legal codes should apply to the treatment of animals as are applied to humans” and he posed the pertinent central questions: “(i) Can man’s claim to being the apex of value in the world be justified?"(ii) If a distinctively religious justification of this claim is offered, what are the moral implications for how humans may treat other forms of life, animals in particular.” 3 Work on Animal Experimentation Masri was one of the first, if not the first person in modern times to write about Islam and Animal Experimentation. In fact, his whole ‘entry’ into this field of research and writing started with a lecture delivered at the International Conference on Religious Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science, held in July 1984, in London, England. Here, Masri presented a paper entitled: Islamic Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science. His other works on the subject appear as follows: 1. The 1984 conference paper was reprinted in Animal Sacrifices: Religious Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science, in 1986 by Temple University Press. Chapter 6: “Animal Experimentation: The Muslim Viewpoint”, pp. 171-197. Designated as the “First Paper” in the discussion that follows. 2. “Islam and Experiments on Animals”, was published in International Animal Action (No. 8), IAAPEA, Hertfordshire, England, published in 1986. Designated as the “Second Paper” in the discussion that follows. 3. In 1987, his views from works cited in #1 and #2 above, were published in two books: “Islamic Concern for Animals (in Arabic and English)” which formed the first chapter of the now classic Animals in Islam, published in 1989, by Compassion in World Farming, The Athene Trust, Petersfield and an abridged version of Animals in Islam which was published without the chapter on stunning and pig meat consumption as Animal Welfare in Islam, by The Islamic Foundation, Leicester, in 2009. 4. Animals in Islam has been published with notes, as Les Animaux en Islam, in 2015, by Driot Des Animaux, translator Sébastien Sarméjeanne, and preface by noted French Islamic writer Malek Chebel and includes the discussion on Animal Experimentation. Masri’s methodology in the First Paper In 1984, there was a paucity of “Islam” and “Animal Welfare” information in the public domain or within academia and Masri had to introduce the basic concepts of Animal Welfare advocacy and rights to both specialists and laypersons. His 1984 paper therefore covers a wider range of subjects, animal experimentation being only the one of them. Through discussing the Quran and Hadith, Masri showed that Islam is replete with injunctions on animal welfare and kind treatment. This paper was revised and re- Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, 1986, “Animal Experimentation: The Muslim Viewpoint”, Ed. Tom Regan, Animal Sacrifices: Religious Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), 171. 3 published in the book Animal Sacrifices. All quotations are from this book, rather than the First Paper, where minor editorial changes were made. In dealing with vivisection, Masri states: When the Prophet came to Medina, after his flight from Mecca in 622 C.E., the people there used to cut off camels’ humps and the fat tails of sheep. The Prophet ordered this odious practice stopped and declared: “Whatever is cut off an animal, while it is alive, is carrion and must not be eaten.” 4 These verses refer to cutting living animals for food or as an offering to idols or gods. But the Islamic prohibition against cutting live animals, especially when pain results, can be extended to vivisection in science…. We are able to support this interpretation… [from Hadith where we find] the principle that any interference with the body of an animal that causes pain or disfigurement is contrary to Islamic precepts.5 Masri then goes on to quote some Hadith in this regard: Another Hadith states: “Jabir told that God’s Messenger forbade striking the face and branding on the face [of animals].” 6 Also, Masri quoted Abu Abbas having reported the Prophet as saying: ‘Do not set up any living creature as a target.”7 He writes of not only physical, but emotional distress too, where he cites the following Hadith of Prophet Muhammad: We were on a journey with the Apostle of God, who left us for a short space. We saw a hummara (a bird) with its two young, and took the young birds. The hummara hovered with fluttering wings, and the prophet returned saying, “Who has injured this bird by taking its young? Return them to her.”8 Masri’s exposition in the Second Paper on Animal Experimentation “Islam and Experiments on Animals” was Masri’s second paper on the subject. He starts out by stating that many cruelties that exist now did not at the time of the Prophet Muhammad. The contents of the Second Paper were included in the books, Islamic Concern for Animals and Animals in Islam in with minor editing, from which we will quote through these books: Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animal Sacrifices, p. 191. Hadith narrated by Abu Waqid al-Laithi. Tirmidhi and Abu Dawud. from Mishkat al-Masabih, English translation by James Robson, in four volumes, p. 874 (Lahore, Pakistan, Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1963). Hereafter referred to as Robson. 5 Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animal Sacrifices, p. 191. 6 Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animal Sacrifices, p. 191. Hadith narrated by Muslim, vol. 1, ch. 3, section 9:265 on “Duty Towards Animals.” Also Yusul al-Kardawi, The Lawful and Unlawful in Islam (in Arabic), (Cairo, Mektebe Vahba, 1977), p. 293 and Robson, p. 872. 7 Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animal Sacrifices, p. 192. Narrated by Abu Abbas. Muslim. Also Robson, p. 876. 8 Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animal Sacrifices, pp. 184-185. Hadith from Muslim.Alfred Guillaume, The Traditions of Islam (Beirut, Lebanon, Khayats Oriental Reprinters, 1966) p. 106. 4 It has been mentioned earlier, that certain kinds of cruelties, which are being inflicted on animals these days, did not exist at the time of …Prophet Muhammad…and, therefore, they were not specifically cited in the law…9 Needs are denoted by the word Al-Masaleh in Arabic. Masri goes on to see how Islamic juristic rules define needs and interests (having defined the hierarchical role of Quran, Hadith and ijtihad (reasoning) in the First Paper). The basic consideration of such rules, Masri states, is that “One’s interest does not annul other’s right.”10 The needs can be split, he adds into: 1. The necessities. 2. The requisites. 3. The luxuries. Then he proceeds to discuss Islamic Juristic Rules to deal with these two types of interests. He cites the following rules11; summaries have been provided in square brackets, by this writer: “That without which a necessity cannot be fulfilled is itself a necessity: Is an experiment really necessary (wajib): if it is, then the following principle come into play”. “What allures to the forbidden is itself forbidden:” [Experiments performed on animals to produce material gains that are forbidden in Islam are forbidden.] “If two evils conflict, choose the lesser evil to prevent the bigger evil: …even genuine experiments on animals are allowed as an exception and as a lesser evil and not a right.” “Prevention of damage takes preference of interests or fulfillment of needs”: [This involves weighing the advantages and disadvantages of an experiment]. “No damage can be put right by [the infliction of] a similar or greater damage: When we damage ourselves with our own follies, we have no right to make animals suffer by inflicting similar or greater damage.” (Masri also has one more rule which is: “No damage can be put right”, which appears redundant, in light of the aforesaid rule). “Resort to alternatives, when the original becomes undesirable.” [This juristic rule can be applied to alternatives to animal experimentations.] “That which becomes permissible for a reason, becomes impermissible by the absence of that reason.” [This refers to the contextual aspect of laws.] “All false excuses leading to damage should be repudiated.” Masri cites two important passages that are applicable to cruelty akin to that in animal experimentation. These are as follows: It was not God who instituted the practice of a slit-ear she-camel, or a she-camel let loose for free pasture, or a nanny goat let loose…(Q. 5:106) Allah cursed him [Satan] for having said: “I shall entice a number of your servants, and lead them astray, and I shall arouse in them vain desires: I shall instruct them to slit the ears of cattle; and most certainly, I shall bid them – so that they will corrupt God’s Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animals in Islam, (Petersfield: The Athene Trust, 1989), 18. Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animals in Islam, p. 19. 11 Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animals in Islam, p. 19. 9 10 creation.” Indeed! He who chooses the Devil rather than God as his patron, ruins himself manifestly (Q:118:119)12 Masri’s conclusion is that: Some research on animals may yet be justified, given the Traditions of Islam, only if the laboratory animals are not caused pain or disfigurement and only if human beings or other animals would benefit because of the research. The most important of all considerations is to decide whether the experiment is really necessary and that there is no alternative for it. Summary of Masri’s Approach Masri, in his articles/books uses: Numerous Hadith, some Quranic verses and Juristic rules to show that Islam is against painful and avoidable animal experimentation. He also uses numerous Quranic verses to show human and animal relationships as they ought to be in the Quran. Primarily, the methodology and sources he uses are nature, the Quran and reason, and he does not involve his discussion in mysticism or appeals to authority, save to corroborate that which he has arrived at through the aforementioned sources. Four Foundational Quranic Principles against Painful Animal Experimentation In an article published13 after Masri’s death, combining further research and some of Masri’s unpublished works, four interrelated principles do clearly emerge that can be applied to the ethics of Animal Experimentation. Let us now discuss what these are: Ecognition 1: All nonhuman animals are a trust from God. Ecognition 2: Equigenic rights do exist and must be maintained. Ecognition 3: All nonhuman animals live in communities. Ecognition 4: All nonhuman animals possess personhood In Animals and Islam and Islamic Concern for Animals, Masri discusses these topics at length but does not define them as four foundational principles and does not apply them all to animal experimentation directly. However, in order to systemize Islamic ethics into a coherent whole, that encapsulates a comprehensive behavioral paradigm, it was sought by this writer, to develop some new terms. One of these is the term Ecognition, which has been coined from Ecological Recognition. It will be shown that the ‘ecognitions’ absolutely prohibit animal experimentation that cause physical or psychological harm to animals, and that the Islamic view is technologically proactive in finding alternatives. In fact, the Islamic view is in complete consonance with the report on animal experimentation prepared by the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics.14 Al-Hafiz B.A. Masri, Animals in Islam, p. 22. Nadeem Haque, “The Principles of Animal Advocacy in Islam: Four Integrated Ecognitions”, Society & Animals 19: (2011) 279-290 14 Andrew Linzey and Clair Linzey, eds., Normalizing the Unthinkable: The Ethics of Using Animals in Research, A report by the Working Group for the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, The Ferrater Mora Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, 2015. 12 13 Ecognition 1: Ownership The following Quranic passages speak of ultimate ownership: To God belongs the dominion over the heavens [all galactical and related intergalactical systems] and the earth: and God has the power over all things. 3:189 Blessed . . . is He to whom belongs the dominion of the heavens [all galactical and related intergalactical systems], and the earth; He who has begotten no son, nor has any partner in His dominion: for it is He who creates, designs and shapes everything, and precisely lays it out through natural laws, that determine its developmental pathway.15 25:1-2 Proper definition of khalifah “Khalifah” in Arabic means a successor. It has been used in all places in the Quran simply as meaning this and does not directly translate as “steward”, “viceregent”, “vicegerent” or “viceroy” of God, that is, as a representative of God16. In fact, khalifah, from the Quran itself can only be properly understood as a relational concept representing the continuity of peoples/tribes etc. In and of itself, there would be nothing special about this, were it not for the fact that human beings are a class of ‘free-willed’ entities that can obey or disobey God. The Quran says, “We offered the trust [amanata] unto the cosmic systems, the earth and the mountains, but they shrank from bearing it, being afraid; but the human being assumed it [i.e. the trust]. [However,] he has proven unjust and ignorant. 33:72 The concept here is that in being grateful to God, the human being can fulfill the trust and therefore, the ‘successor’ is a trustee of the mizan (al-mizan (the balance) is one of the four ecognitions, soon to be discussed). This poses the critical question: How is the khalifah (successor) to behave? In order to be put things where they belong (the opposite meaning of the word zulm) and calm, knowledgeable and rational (the opposite of juhl), one has to observe the universe purpose and realize many of its attributes including that the rest of the Universe is greater than the human being and that the human being has been created to see who will pass the test of the universe: And He it is who has created the universe and earth in six periods; and His throne [of power] was on the water, in order to test you to see which of you is best in terms of the performance of deeds. 11:7 With the verse on the creation of the universe being greater than the creation of the human being, this fact ought to remind human beings to be humble before creation and that which created it. The place of the human being, or the khalifah is that of being an animal, categorized by the Qurʾanic word dabbah—a water/carbon-based creature that can move spontaneously, as described in verse 24:45. Not surprisingly, in the Quran, it is advised that human-beings be sincerely humble: 15 The words describing physical processes used in the translation by this writer (Nadeem Haque) are based on their Arabic root meanings and the shades of complementary meanings, to give a closer and more accurate rendition of the actual Quranic message, usually lost in the translation in contemporary English translations of the Quran, especially concerning scientific matters. 16 Sarra Tlili, Animals in the Quran, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 115-123. See an extensive discussion on this point in this book. It is He who has made the earth compliant. So walk in its tracts and partake of the provisions laid out by Him ⎯ bearing in mind that unto Him is the ultimate return. 67:15 Do not walk on the earth in overbearance ⎯ for you can neither split the earth asunder, nor can you rival the mountains in stature. Such arrogance ⎯ the wickedness of it all ⎯ is hateful in the sight of your Sustainer. 17:37-38 Ecognition 2: The Equigenic Principle This refers to the dynamic equilibrium in nature. In the Quran, it is stated: It is He [God] who has created the expansive universe and established the balance [mizan], so that you may not disrupt the balance. Therefore, weigh things in equity and do not fall short of maintaining that balance. 55:7-9 We have surely sent messengers with clear evidences, and sent them with the Book [the Qurʾān] and the Balance [the Equigenic Principle], so that human beings may behave with equity. 57:25 The term Equigenic (originally used and discussed in From Facts to Values)17 is coined from: Equi, meaning equal (balanced) and genic (origin). This has two significances: 1. Rights based in the Origin of Equilibrium in Nature (written into the inception – the Big Bang). 2. Origin of Rights based on Equilibrium in Nature. That is to say, rights are projected onto us by observing the dynamic balance of nature, through realizing the interconnections of nature and realizing that they are not man-made or synthetic, but truly natural rights. Equigenic Principle Implies Design and Reason The Equigenic principle conveys the balance and precision and an interesting mathematical observation needs to be mentioned as an aside: The main verse on the balance occurs exactly in the midpoint of the Quran in Chapter 57, in terms of chapter numbers. The Quran has 114 chapters (114 divided by 2 is 57). In fact, in the Quran itself mentions the “Goldilocks Zone”, 1,400 years ago when the world was in its Dark Ages, and most people believed in a flat earth: He (God) has appointed, precisely established and positioned the earth [both the planet as a whole, and the earth’s crust itself] for the maintenance and development18 of sentient life forms [both humans and nonhumans]. 55:10 Nadeem Haque, From Facts to Values: Certainty, Order, Balance and their Universal Implications, (Toronto, Optagon Publications Ltd., 1995). 18 The word wada-aha, used in this passage from the Qurʿān, means a combination of all these meanings: appoint; precisely establish and position; and maintain and develop, as a careful study of the usage of this word in the Qurʿān attests. 17 Al-mizan (the balance) therefore is at the core of the Equigenic Principle, and the Equigenic Principle is brought about by Ecognition. Elaboratng on the implications of the Equigenic Principle, it becomes clear from studying the Quran that: Those who are cognizant of the design of the Universe; observe the myriad signs are the ones who use reason and therefore do not engage in acts which are unclean (disruptive of the natural order): one of the Arabic words for unclean being rijs. In Figure 1, the causal nexus of this type of thinking is illustrated and its connection to the word “Islam”, where each concept leads to the next, as follows, noting the fact that the root of the word zulm is “to dislocate/not put things where they belong”: Figure 1 One of the meanings of the word Islam is “Peace” (derived from the root s-l-m). Ecognition 3: Animals in Communities The following Quranic verse implies that animal communities are similar in principle and in many details to human communities and that animals are in many ways are ‘like us’: There is not a nonflying and two-winged flying [water/carbon-based] creature, but they are in communities like yourselves. 6:38 Ecognition 4: Animal Personhood Animal personhood is established in the Quran by three concepts; animal communication, intelligence and consciousness. Animal Communication The Qurʾan, for instance, describes ants communicating meaningfully with one another. An ant is on the lookout and warns fellow ants of impending doom: [A]nd then they were led forth in orderly ranks, until, when they came upon a valley of ants, an ant exclaimed: “O you ants! Get into your dwellings, lest Solomon and his hosts crush you unawares.” 27:17-18 The ant identifies Solomon and his group, and her own ant community, and seeks to avoid being killed. Solomon, we are told, not only understood this communication but took delight in the discourse: Thereupon [Solomon] smiled joyously at her communication. 27:19 Modern scientific corroboration of Quranic verse is exhibited in the following happenstance during field invesigations. E. O. Wilson encountered a variety of chemicals in his observations of ants: One message means “Follow me.” Another: “On guard! A threat to the public good is present.” (This was the message in the scent that Wilson had evoked by picking apart the tree stump in Rock Creek Park; the alarm pheromone [chemical signal] of [the ant species] Acanthomyops is essence of citronella.) (Wright, 1988, pp. 128-129) The ant on the lookout is female in the Quran, also in accord with field observations. Animal Intelligence The Arabic word for reason in the Quran is ‘aql, from the root ‘aqala, which is based on iqal, a word which denotes a cord used to tie a camel’s legs so that it does not run away, and which therefore means “to bind” and hence “to secure something.” Since nonhuman animals also interconnect things to attain goals, they also use aql. Consciousness: The Islamic Concept of Animal ‘Souls’ Many people hold that animals possess no “soul” and hence are not secure by any “religious” sanction against mistreatment and slaughter. This notion is quite contrary to Islamic teachings. Alongside nafs, there is another term in the Quran, used in connection with life: ruh. Ruh is generally translated as “soul”: “And they will ask you about the ruḥ. Say: “This ruḥ is by my Sustainer’s command, and you have been granted but a small portion [of the body] of knowledge [needed to know its exact nature.]” 17:85 Ruh is brought into existence by Allah’s creative commandment, and is sustained by His will. To explain ruh requires a treatise on the subject.19 Both nafs and ruḥ are connected to the created consciousness that arises from the infinitely rich imagination of God, that is, from His transcendent ever-existing consciousness, since, logically speaking, created consciousness can only come from and be sustained by a higher consciousness, according to the Qur’ān. st Concepts aiming for Optimal 21 Century Human and Animal Relations The concept of Personhood in relation to consciousness and creative evolution produces what can be refered to as “Affinity”: Affinity is a much deeper and more all-encompassing than the concept of ‘brotherhood’ which Muslims usually speak about. It also incorporates the concept of brotherhood, as a subset, based on a solid linkage of our interconnections as living beings. This emerging New Synthesis is what is exhibited by modern research into nature and animals and documents such as the Quran; these sources of knowledge provide the motivation and methodology that can lead to Affinity. How so? Firstly, from the Quran, it can be shown that all life evolved from constituents in clay and water. Furthermore, all consciousness in creatures has its origin from One Creator (as the claimed solution to the mind body problem) according to Quranic analysis.20 Remarkably, one word in the Quran captures the concept of evolution and common source for consciousness. This word is Rabb, which means Sustainer, that is, one who creates and sustains all consciousness and creation. Rabb also means: The Evolver unto completion of nature and its constituents, and the entire universe, or the Cherisher of something from one stage to another until it reaches perfection. The consequences of such a concept are shown in Fig. 2. In From Microbits to Everything: Universe of the Imaginator, Volume 2: The Philosophical Implications, published in Toronto by Optagon Publications limited in 2007, Nadeem Haque and M. Muslim offer a detailed examination of the ruh, mind and consciousness, and argue for a framework that resolves the mind/body problem. 20 Nadeem Haque and M. Muslim, From Microbits to Everything: Universe of the Imaginator: Volume 2: The Philosophical Implications, (Toronto: Optagon Publications Ltd., 2007) 163-277. 19 Most people in both East and West, Muslims and non-Muslims, are not aware that the Quran not only espouses creative evolution, but that the origin of evolutionary theory in the West (though now divorced from God) in mainstream science has its origin in the Quran and the very early Islamic thinkers. For example, the word yaum in Arabic does not mean day only, but it can be used to mean periods, as per Quranic usage. The Earth was created in six periods and God did not need to rest after that! These ideas were taken up by the first French Evolutionists during the Enlightenment and then passed on to Darwin (who was learning Arabic)21. The conclusion is that: the origin of all animals (including humans) is one: therefore, individuality is from same source: Do those who cover the truth not see that the rest of the universe and the earth were one piece and We (God) ripped them apart and made every living thing (dabbat (carbon-based animal)) from water. 21:30 Rabb Evolver Figure 2 Sustainer Affinity Empathy Compassion Action Justice Peace Affinity is further reinforced for a Muslim by the following consideration: What does it mean that: “All nonhuman animals prostrate to God”, according to the Quran? As was astutely pointed out by Masri: “The Qurʾān (24:41) further tells us that nonhuman animals, who offer their obeisance to God in every movement, know what they are doing. This verse makes it abundantly clear that they are capable of 21 Mehmet Bayrakdar, “Al-Jahiz and the Rise of Biological Evolutionism”, The Islamic Quarterly, Third Quarter, 1983. consciously performing such acts, and, being Muslim (always in total submission to God (one of the complementary meanings of Islam)), they coexist with their environs in constant, natural genuflection.” In this sense, they submit to God (the prime meaning of Islam): Do you not see that unto God prostrate all things that are in the universe and on earth the sun, the moon, the stars, the mountains, the trees, the animals, and a large number among mankind? However, there are many who deserve chastisement... 22:18 Ecognition Implications for Animal Experimentation The four Ecognitions lay the foundation for rethinking our treatment of animals. Legislation regarding animals must be seen and assessed in light of each of these Ecognitions, and in light of the interrelationships between these Ecognitions. With the proper Islamic view of animal personhood, would we cage animals for transportation to labs (Ecognition 4: Personhood)? If we are the trustees of the balance (Ecognition 2) because God is the owner (Ecognition 1), then are we not supposed to uphold our responsibilities (i.e. nonharm to animals to maintain equilibrium) by being conscious of a higher power to whom we are accountable? If the rainforest, sustaining countless life forms, and life forms sustaining forests belong to God, would we purposefully desecrate His property (Ecognition 1) by capturing animals for experimentation (Ecognition 2: al-mizan (The Balance))? If animals possess personhood and dwell in communities (Ecognition 3), how can animal experimentation be allowed? Are they then not like human beings (the supposed “chosen species”, to quote Masri?) If animals have personhood (Ecognition 4) and feelings (like us), should we treat them cruelly? If we perform painful experiments on animals, do we not violate all four Ecognitions? Conclusion The Quranic and therefore Islamic perspective lays the foundation of nature and its link to the Creator on a rational basis (Ecognitions). It reinforces the position paper of the Oxford Centre’s on Animal Experimentation. Figure 3: The Quranic Ethical System for Animal Welfare Issues It lays a logical, ethical and motivational (taqwa: God-consciousness) structure, where consistent scripture and evidence from science are united (or re-united) on this issue. The Quranic position fosters affinity between human and non-human sentience, diametrically opposed to anthropocentrism, selfishness, and greed ⎯ towards a rational and compassionate teleo-centric perspective that prohibits physically and psychologically harmful Animal Experimentation.