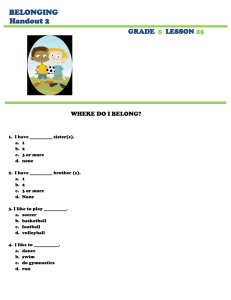

Engaging Marginalized Middle-Level Students: Sense of Belonging

advertisement