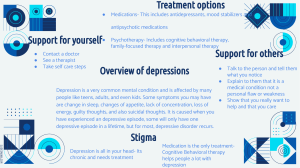

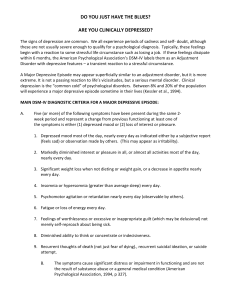

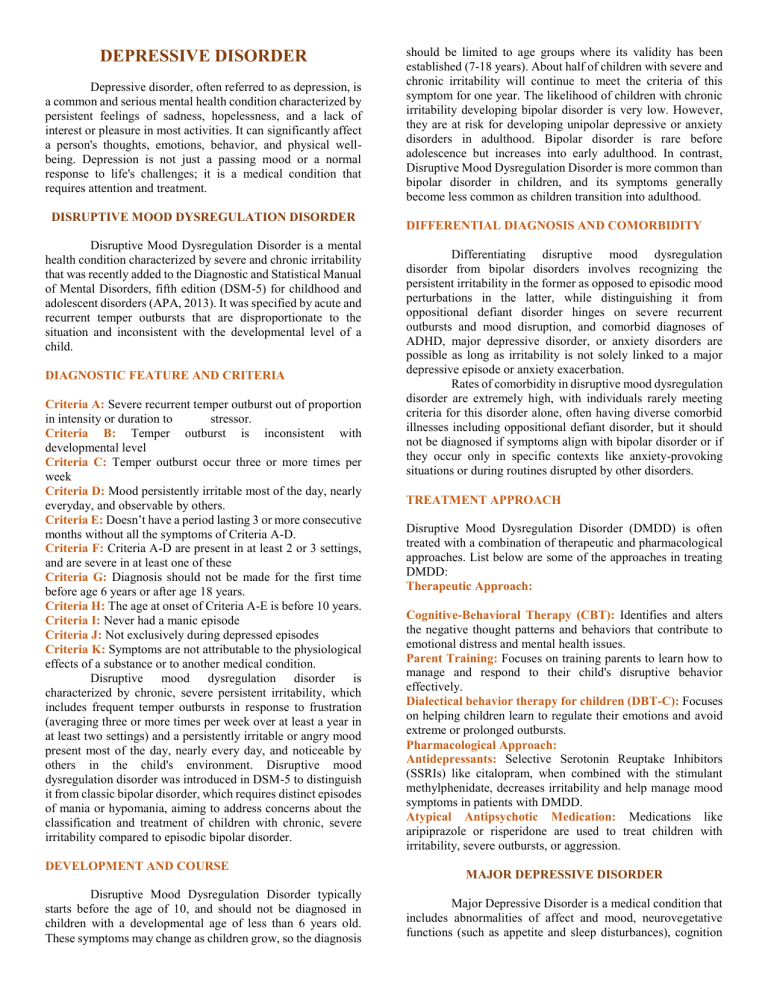

DEPRESSIVE DISORDER Depressive disorder, often referred to as depression, is a common and serious mental health condition characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a lack of interest or pleasure in most activities. It can significantly affect a person's thoughts, emotions, behavior, and physical wellbeing. Depression is not just a passing mood or a normal response to life's challenges; it is a medical condition that requires attention and treatment. DISRUPTIVE MOOD DYSREGULATION DISORDER Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder is a mental health condition characterized by severe and chronic irritability that was recently added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) for childhood and adolescent disorders (APA, 2013). It was specified by acute and recurrent temper outbursts that are disproportionate to the situation and inconsistent with the developmental level of a child. DIAGNOSTIC FEATURE AND CRITERIA Criteria A: Severe recurrent temper outburst out of proportion in intensity or duration to stressor. Criteria B: Temper outburst is inconsistent with developmental level Criteria C: Temper outburst occur three or more times per week Criteria D: Mood persistently irritable most of the day, nearly everyday, and observable by others. Criteria E: Doesn’t have a period lasting 3 or more consecutive months without all the symptoms of Criteria A-D. Criteria F: Criteria A-D are present in at least 2 or 3 settings, and are severe in at least one of these Criteria G: Diagnosis should not be made for the first time before age 6 years or after age 18 years. Criteria H: The age at onset of Criteria A-E is before 10 years. Criteria I: Never had a manic episode Criteria J: Not exclusively during depressed episodes Criteria K: Symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or to another medical condition. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is characterized by chronic, severe persistent irritability, which includes frequent temper outbursts in response to frustration (averaging three or more times per week over at least a year in at least two settings) and a persistently irritable or angry mood present most of the day, nearly every day, and noticeable by others in the child's environment. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder was introduced in DSM-5 to distinguish it from classic bipolar disorder, which requires distinct episodes of mania or hypomania, aiming to address concerns about the classification and treatment of children with chronic, severe irritability compared to episodic bipolar disorder. DEVELOPMENT AND COURSE Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder typically starts before the age of 10, and should not be diagnosed in children with a developmental age of less than 6 years old. These symptoms may change as children grow, so the diagnosis should be limited to age groups where its validity has been established (7-18 years). About half of children with severe and chronic irritability will continue to meet the criteria of this symptom for one year. The likelihood of children with chronic irritability developing bipolar disorder is very low. However, they are at risk for developing unipolar depressive or anxiety disorders in adulthood. Bipolar disorder is rare before adolescence but increases into early adulthood. In contrast, Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder is more common than bipolar disorder in children, and its symptoms generally become less common as children transition into adulthood. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND COMORBIDITY Differentiating disruptive mood dysregulation disorder from bipolar disorders involves recognizing the persistent irritability in the former as opposed to episodic mood perturbations in the latter, while distinguishing it from oppositional defiant disorder hinges on severe recurrent outbursts and mood disruption, and comorbid diagnoses of ADHD, major depressive disorder, or anxiety disorders are possible as long as irritability is not solely linked to a major depressive episode or anxiety exacerbation. Rates of comorbidity in disruptive mood dysregulation disorder are extremely high, with individuals rarely meeting criteria for this disorder alone, often having diverse comorbid illnesses including oppositional defiant disorder, but it should not be diagnosed if symptoms align with bipolar disorder or if they occur only in specific contexts like anxiety-provoking situations or during routines disrupted by other disorders. TREATMENT APPROACH Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD) is often treated with a combination of therapeutic and pharmacological approaches. List below are some of the approaches in treating DMDD: Therapeutic Approach: Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Identifies and alters the negative thought patterns and behaviors that contribute to emotional distress and mental health issues. Parent Training: Focuses on training parents to learn how to manage and respond to their child's disruptive behavior effectively. Dialectical behavior therapy for children (DBT-C): Focuses on helping children learn to regulate their emotions and avoid extreme or prolonged outbursts. Pharmacological Approach: Antidepressants: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) like citalopram, when combined with the stimulant methylphenidate, decreases irritability and help manage mood symptoms in patients with DMDD. Atypical Antipsychotic Medication: Medications like aripiprazole or risperidone are used to treat children with irritability, severe outbursts, or aggression. MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER Major Depressive Disorder is a medical condition that includes abnormalities of affect and mood, neurovegetative functions (such as appetite and sleep disturbances), cognition (such as inappropriate guilt and feelings of worthlessness), and psychomotor activity (such as agitation or retardation). It is the most prevalent form of depressive disorder that significantly affects an individual’s everyday life, including their thoughts, behavior, and well-being. DIAGNOSTIC FEATURE AND CRITERIA Criteria A: Five (or more) of the following symptoms must be present during the same two-week period and represent a change from previous functioning. At least one of the symptoms must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. 1. Depressed or Low Mood 2. Anhedonia (loss of interest and pleasure) 3. Weight Gain or Loss 4. Loss or increase of appetite 5. Insomnia or Hypersomnia 6. Psychomotor agitation or retardation 7. Unexplained Fatigue 8. Difficulty in concentrating 9. Recurrent thoughts of death Criteria B: The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Criteria C: The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition. Criteria D: The occurrence of the major depressive episode is not better explained by other specified and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. Criteria E: There has never been a manic or hypomanic episode. Major depressive disorder is diagnosed when an individual experiences nearly daily symptoms, including persistent depressed mood, loss of interest in most activities, appetite and sleep disturbances, psychomotor changes, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, difficulty concentrating, thoughts of death or suicide, and functional impairment, lasting for at least 2 weeks, with careful consideration for potential cooccurring medical conditions. DEVELOPMENT AND COURSE Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) can manifest at any age but becomes more likely with puberty. It has variable courses; some experience chronic symptoms, while others have periods of remission. Chronicity of depressive symptoms is associated with underlying personality, anxiety, and substance use disorders and lower chances of full recovery. Recovery often starts within 3 months for 2 in 5 individuals and within 1 year for 4 in 5. The recent onset correlates with better near-term recovery, while factors like psychosis, anxiety, and severity hinder recovery. Recurrence risk decreases with remission duration but rises with severe prior episodes and multiple episodes. Even mild symptoms during remission predict recurrence risk. Some initially diagnosed with major depressive disorder may later have bipolar disorder, especially with onset in adolescence, psychotic features, or a family history of bipolar illness. Also, Major depressive disorder can sometimes transition into schizophrenia, more commonly than the reverse. Suicide attempts become less likely in middle and late life, but the risk of completed suicide remains. Early-onset depression is more likely to involve personality disturbances. The course of major depressive disorder typically remains consistent with age, and recovery times remain stable over time. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND COMORBIDITY Distinguishing between major depressive episodes and manic episodes with irritable mood or mixed episodes requires careful evaluation of manic symptoms, while diagnoses like mood disorder due to another medical condition, substance/medication-induced depressive or bipolar disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, and normal sadness have distinct criteria, such as medical causation, substance involvement, symptom characteristics, stressors, and severity/duration considerations. Major depressive disorder often co-occurs with other conditions, including substance-related disorders, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and borderline personality disorder. TREATMENT APPROACHES Several studies have shown that Medications and Psychological interventions are the most effective way to treat an individual with a Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), especially when combining both of these treatments. There are many types of antidepressants that's used for treating depression. List below are the commonly known medications: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These drugs are considered safer and generally cause fewer bothersome side effects than other types of antidepressants. It includes citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva), sertraline (Zoloft) and vilazodone (Viibryd) which helps increase the level of serotonin in the brain. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). This medication includes duloxetine (Cymbalta), venlafaxine (Effexor XR), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq, Khedezla) and levomilnacipran (Fetzima) which helps regulate the mood and relieve depression. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). This drug includes tranylcypromine (Parnate), phenelzine (Nardil) and isocarboxazid (Marplan) which helps increase the levels of certain neurotransmitters in the brain to boost the mood and improve other depressive symptoms. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, on the other hand, is one of the commonly used psychological interventions in treating depression. It focuses on identifying how negative thoughts, false beliefs and attitudes affect the feelings and actions of an individual. PERSISTENT DEPRESSIVE DISORDER (Dysthymia) Persistent depressive disorder (PDD), is a chronic depression that persists for most days over a period of 2 years (or longer). It also originally known as dysthymia, came from the Greek roots dys, meaning "ill" or "bad," and thymia, meaning "mind" or "emotions." The terms dysthymia and dysthymic disorder referred to a mild, chronic state of depression. part of the psychiatric evaluation to provide context to symptoms. DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA AND FEATURE The general symptoms are milder than major depressive disorder but additional symptoms involved in MDD may develop during dysthymia and lead to a diagnosis of MDD. They may have episodes of MDD at least once at some point and the comorbidity of both these disorders is known as a double depression, the co-existence of major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. It is frequently comorbid with other psychiatric and medical conditions. As always, the above symptoms and criteria must cause significant distress and impairment in critical areas of functioning to meet the threshold for diagnosis. To meet the diagnostic criteria of PDD, two or more of the following must be present or cannot be absent for more than 2 consecutive months: • Poor appetite or overeating • Insomnia or hypersomnia • Low energy or fatigue • Low self-esteem • Poor concentration • Feelings of hopelessness DEVELOPMENT AND COURSE Criteria A During the 2 year period of the disturbance, the person has never been without symptoms from the above two criteria for more than 2 months at a time. Criteria B Criteria for MDD may be continuously present for 2 years, in which case patients should be given comorbid diagnoses of persistent depressive disorder and MDD. Criteria C There has never been a manic episode, a mixed episode, or a hypomanic episode and the criteria for cyclothymia have never been met. Criteria D The symptoms are not better explained by a psychotic disorder. Criteria E The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse or a medication) or a general medical condition. Criteria F The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning. For adults, symptoms of depression must be experienced more often than not for at least two years prior. On the other hand, for children or adolescents, the mood can be irritable instead of depressed, and the time requirement was lowered to 1 year. Affected patients may be habitually gloomy, pessimistic, humorless, passive, lethargic, introverted, hypercritical of self and others, and complaining. Patients with PDD are also more likely to have underlying anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, or personality (ie, borderline personality) disorders. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND COMORBIDITY Differential diagnosis for persistent depressive disorder includes ruling out medical/organic causes as well as screening for other DSM diagnoses, including major depression, bipolar, psychotic disorders, substance-induced states, and personality disorders. Also, a thorough assessment of patients presenting with mental health symptoms involves ruling out medical and biological causes with their current and past medical history, as well as current medications, should be Symptoms of PDD typically begin insidiously during adolescence and may persist for 2 years or more in decades. It can have early onset (before age 21 years) or late onset (at age 21 years or older) and the number of symptoms often fluctuates above and below the threshold for major depressive episodes. There are no known biological causes that apply consistently to all cases of persistent depressive disorder, which suggests diverse origins for the disorder, but there are a number of factors that are believed to play a role, including: • Brain chemistry: The balance of neurotransmitters in the brain can play a role in the onset of depression. Some environmental factors, such as prolonged stress, can actually alter these brain chemicals. • Environmental factors: Situational variables such as stress, loss, grief, major life changes, and trauma can also cause depression. • Genetics: Having close family members with a history of depression or doubles a person's risk of also developing depression. When it comes to gender, the prevalence of persistent depressive disorder is two times higher in females than in males, and this is fairly consistent worldwide. While frequency in age groups for persistent depressive disorder, depression rates tend to decrease with increasing age, especially age greater than 65. Admittedly, estimates of depression may be low in the elderly due to increasing confounding physical disorders with age. TREATMENT APPROACHES A combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapy has consistently been shown to be the most effective line of treatment for people diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder. In psychotherapy it may involve a range of different techniques, but two that are often used are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT). ● Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Focuses on learning to identify and change the underlying ● negative thought patterns that often contribute to feelings of depression. ● ● ● Interpersonal Therapy (IPT): Similar to CBT but focuses on identifying problems in relationships and communication and then finding ways to make improvements in how you relate to and interact with others. ● ● ● For antidepressants there are different types that may be prescribed to treat PDD, including: • Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): These medications include sertraline Zoloft (sertraline) and Prozac (fluoxetine) that works by increasing serotonin levels in the brain, which can help improve and regulate mood. • Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): These medications include Cymbalta (duloxetine) and Pristiq (desvenlafaxine) that also works by increasing the amount of serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain. PREMENSTRUAL DYSPHORIC DISORDER Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is conceptualized as a more serious form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). It causes physical and emotional symptoms every menstrual cycle in the week or two before your period. It is characterized by dysphoria, mood lability, irritability, anxiety, and cognitive changes that occur repeatedly during the premenstrual phase of the cycle and resolve around the time of (or after) menses. DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES AND CRITERIA Currently, PMDD is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) as a separate entity under Depressive disorders, with the criteria for diagnosis as follows: Criterion A - At least 5 of the following 11 symptoms (including at least 1 of the first 4 listed) should be present: ● Markedly depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts ● Marked anxiety, tension, feelings of being “keyed up” or “on edge” ● Marked affective lability ● Persistent and marked anger or irritability or increased interpersonal conflicts ● Decreased interest in usual activities (eg, work, school, friends, and hobbies) ● Subjective sense of difficulty in concentrating ● Lethargy, easy fatigability, or marked lack of energy ● Marked change in appetite, overeating, or specific food cravings ● Hypersomnia or insomnia ● A subjective sense of being overwhelmed or out of control Other physical and behavioral symptoms: ● breast tenderness or swelling ● pain in your muscles and joints headaches feeling bloated changes in your appetite, such as overeating or having specific food cravings sleep problems increased anger or conflict with people around you becoming very upset if you feel that others are rejecting you. Criterion B - symptoms severe enough to interfere significantly with social, occupational, sexual, or scholastic functioning. Criterion C - symptoms discretely related to the menstrual cycle and must not merely represent an exacerbation of the symptoms of another disorder, such as major depressive disorder, panic disorder, dysthymic disorder, or a personality disorder (although the symptoms may be superimposed on those of these disorders). Criterion D - criteria A, B, and C are confirmed by prospective daily ratings during at least 2 consecutive symptomatic menstrual cycles. The diagnosis may be made provisionally before this confirmation. For some people, symptoms of PMDD last until menopause. And so, women with moderate-to-severe PMS or PMDD experience more quality-of-life detriments and workproductivity losses and incur greater healthcare costs than women with no or only mild symptoms, as some symptoms are severe enough to interfere with functioning at home, school, or work. It occurs in an estimated 5% of women, and if left untreated, may become more severe and extend in duration over time. DEVELOPMENT AND COURSE The onset of PMDD, symptoms typically emerge during the mid- to late twenties and follow a chronic course if left untreated. In women with PMDD, symptoms tend to worsen over time but discontinue during interruptions of the ovulatory cycle (i.e., menopause, pregnancy, and ovariectomy). The main cause of PMDD is still not known. However, decreasing levels of estrogen and progesterone hormones after ovulation and before menstruation may trigger symptoms. Also, serotonin, a brain chemical that regulates mood, hunger and sleep, may also play a role as it changes throughout your menstrual cycle.There are also risk factors associated with the development of PMS/PMDD which are the following: ● Past traumatic events: Traumatic events or even interpersonal trauma associated with stress and preexisting anxiety disorders are risk factors for the development of PMDD. ● Cigarette smoking: There is a strong association of moderate-to-severe forms of PMS with current smoking status compared to non-smokers because of hormonal sensitivity. The risk is elevated even for former smokers, and the of incident PMS tends to increase with the quantity of cigarette smoking (20 pack-years). Further, the risk of PMDD is significantly higher for women who began smoking during adolescence. ● Genetics: Some research suggests that increased sensitivity to changes in hormone levels may be caused by genetic variations or from inherited disorders that might have caused PMDD. ● ● DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND COMORBIDITY Lifetime comorbidity rates are high (30–70%), PMDD may put women at risk for later depression, including perimenopausal, postpartum depression and some have previous history of a major depressive episode which is the most common comorbidity with PMDD. Conversely, mood or anxiety disorders may put women at risk for later development. As symptoms of PMDD can overlap with other psychiatric disorders, most importantly major depression, it is imperative to rule out another existing disorder before making the diagnosis of PMS/PMDD. The key factor in making the diagnosis is the temporal association of symptoms with the menstrual cycle. Some common differentials include: ● Major depressive disorder: Depression symptoms include low mood, low energy, appetite change, sleep disturbance, difficulty concentrating, and thoughts of suicide. Roughly half the cases of PMS/PMDD can have a coexisting diagnosis of depression. A diagnosis of PMS or PMDD may predate a diagnosis of depression or depression and PMDD may coexist. Criteria for the diagnosis of these disorders are different but not exclusive. ● Thyroid disease (hyperthyroid or hypothyroid): Hypothyroid symptoms and signs include weight gain, constipation, cold intolerance, depression, dry skin, and delayed deep tendon reflexes. Hyperthyroid signs and symptoms include weight loss, poor sleep, heat intolerance, heart rhythm disturbance such as atrial fibrillation, and hyperreflexia. ● Generalized anxiety disorder: Symptoms of anxiety include palpitations and feelings of fear. Triggers may be identified for anxiety attacks, and the patient shows avoidance of these triggers. Chronic or situational anxiety does not vary with the menstrual cycle. Generalized anxiety disorder and PMDD may coexist. Criteria are different but not exclusive. ● Mastalgia: Symptoms of mastalgia may be limited to just breast tenderness and swelling, and mastalgia may be present at times other than during the luteal phase but worsen during the luteal phase. There are also Assessment Scales used to acquire a certain and exact diagnosis of the PMDD, and these are the following: ● Premenstrual Symptom Screening Tool (PSST): A questionnaire used to diagnose PMDD with 19 items that allow the patient to rate the severity of their symptoms. ● Calendar of Premenstrual Experiences (COPE): Includes 22 symptoms grouped into 4 categories: mood reactivity, autonomic/ cognitive, appetitive, and related to fluid retention. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS): This scale is used in 1999 to rate each of the 4 core symptoms of PMDD: mood swings, irritability, tension, and depression. The scale consisted of a 100 vertical line labeled 0 or “no symptom” at the left end and 100 or “severe” at the right. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): This scale consists of 24 items, out of which 21 items are grouped into 11 distinct symptoms and 3 functional impairment items. The items are rated from 1 (not at all) to 6 (extreme). TREATMENT APPROACHES Treatment modalities for PMDD can be divided into 2 categories: 1. Non-Pharmacological Methods ● Exercise: Get regular aerobic exercise throughout the month to reduce the severity of PMS symptoms. As it improves symptoms through elevation of betaendorphin levels. ● Dietary modifications: Increased intake of complex carbohydrates or proteins ("slow-burning fuels"); healthy diet is believed to increase tryptophan availability, leading to increased serotonin levels. ● Stress management: Relaxation, meditation, yoga, and breathing techniques. 2. ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Pharmacological Methods Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SRIs): SRIs have been proven to be effective in the treatment of severe mood and somatic symptoms of PMDD Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): Has been shown to be an effective treatment for mood and anxiety disorders and has been shown to help people cope better with physical symptoms, such as pain. However, effectiveness to PMDD still requires further study. Benzodiazepines (BZDs): BZDs have been found to be effective only in women with severe anxiety and premenstrual insomnia. However, since there is a risk of dependence, careful monitoring is required, especially in cases with reported prior substance abuse. Drospirenone (a gestagen): Particularly found to be effective in treating PMDD symptoms because of its anti-aldosterone and anti-androgenic effects. Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs): Although widely used in clinical practice, their efficacy in treating PMDD has not been strongly supported by evidence. Women on OCP experience more hormone-related symptoms on hormone-free days, and hence OCP treatment with fewer hormone-free days might be beneficial to these women. Other medicines (such as Depo-Lupron) suppress the ovaries and ovulation, although the side effects that occur are similar to those occurring in women in menopause Pain relievers such as aspirin or ibuprofen that may be prescribed for headache, backache, menstrual cramps, and breast tenderness. SUBSTANCE/MEDICATION-INDUCED DEPRESSIVE DISORDER Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder is a specific type of depressive disorder that is triggered by the use of a substance, such as drugs or medications. The diagnosis of this disorder is typically made based on specific criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), which is a widely accepted reference for mental health professionals. DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA A. A prominent and persistent disturbance in mood that predominates in the clinical picture and is characterized by depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities. B. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings of both (1)and(2): 1. The symptoms in Criterion A developed during or soon after substance intoxication or withdrawal or after exposure to a medication. 2. The involved substance/medication is capable of producing the symptoms in Criterion A. C. The disturbance is not better explained by a depressive disorder that is not substance/medication-induced. Such evidence of an independent depressive disorder could include the following: The symptoms preceded the onset of the substance/medication use; the symptoms persist for a substantial period of time (e.g., about 1 month) after the cessation of acute withdrawal or severe intoxication; or there is other evidence suggesting the existence of an independent nonsubstance/medication-induced depressive disorder (e.g., a history of recurrent non-substance/medicationrelated episodes). D. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium. E. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Note: This diagnosis should be made instead of a diagnosis of substance intoxication or substance withdrawal only when the symptoms in Criterion A predominate in the clinical picture and when they are sufficiently severe to warrant clinical attention. DIAGNOSIS FEATURES The diagnostic features of substance/medicationinduced depressive disorder include the symptoms of a depressive disorder, such as major depressive disorder; however, the depressive symptoms are associated with the ingestion, injection, or inhalation of a substance (e.g., drug of abuse, toxin, psychotropic medication, other medication), and the depressive symptoms persist beyond the expected length of physiological effects, intoxication, or withdrawal period. As evidenced by clinical history, physical examination, or laboratory findings, the relevant depressive disorder should have developed during or within 1 month after use of a substance that is capable of producing the depressive disorder (Criterion Bl). In addition, the diagnosis is not better explained by an independent depressive disorder. Evidence of an independent depressive disorder includes the depressive disorder preceded the onset of ingestion or withdrawal from the substance; the depressive disorder persists beyond a substantial period of time after the cessation of substance use; or other evidence suggests the existence of an independent nonsubstance/medication-induced depressive disorder (Criterion C). This diagnosis should not be made when symptoms occur exclusively during the course of a delirium (Criterion D). The depressive disorder associated with the substance use, intoxication, or withdrawal must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning to qualify for this diagnosis (Criterion E). Some medications (e.g., stimulants, steroids, Ldopa, antibiotics, central nervous system drugs, dermatological agents, chemotherapeutic drugs, immunological agents) can induce depressive mood disturbances. Clinical judgment is essential to determine whether the medication is truly associated with inducing the depressive disorder or whether a primary depressive disorder happened to have its onset while the person was receiving the treatment. For example, a depressive episode that developed within the first several weeks of beginning alpha-methyldopa (an antihypertensive agent) in an individual with no history of major depressive disorder would qualify for the diagnosis of medication-induced depressive disorder. In some cases, a previously established condition (e.g., major depressive disorder, recurrent) can recur while the individual is coincidentally taking a medication that has the capacity to cause depressive symptoms (e.g., L-dopa, oral contraceptives). In such cases, the clinician must make a judgment as to whether the medication is causative in this particular situation. A substance/medication-induced depressive disorder is distinguished from a primary depressive disorder by considering the onset, course, and other factors associated with the substance use. There must be evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings of substance use, abuse, intoxication, or withdrawal prior to the onset of the depressive disorder. The withdrawal state for some substances can be relatively protracted, and thus intense depressive symptoms can last for a long period after the cessation of substance use. DEVELOPMENT AND COURSE The development and course of Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder are closely tied to the use of substances or medications and can vary depending on several factors, including the type of substance or medication involved, individual susceptibility, and treatment interventions. Here's an overview of the development and course of this disorder, along with relevant references: DEVELOPMENT 1. Exposure to Substances/Medications: The disorder develops when an individual is exposed to a substance (e.g., drugs, alcohol) or medication that can trigger depressive symptoms. These substances may include 2. alcohol, stimulants, opioids, sedatives, medications with depressant effects, or others. Temporal Relationship: Depressive symptoms typically emerge during or shortly after the use of the substance, withdrawal from the substance, or exposure to a medication. It's crucial to establish a temporal relationship between the substance use/exposure and the onset of depressive symptoms. COURSE 1. Acute Phase: During the acute phase, individuals experience significant depressive symptoms that are related to substance use or medication exposure. These symptoms can include a persistently low mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, changes in appetite or weight, sleep disturbances, and impaired concentration. 2. Duration: The duration of Substance/MedicationInduced Depressive Disorder can vary. It may be relatively short-lived, especially if related to acute intoxication or withdrawal. In some cases, depressive symptoms may persist for a more extended period after substance use has ceased. 3. Severity: The severity of symptoms can range from mild to severe, depending on the specific substance, the individual's vulnerability, and the duration of exposure. In some instances, individuals may experience severe depressive symptoms requiring immediate attention. 4. Remission: In cases where the disorder is related to substance use, depressive symptoms often improve or remit once the substance is no longer in use, or withdrawal symptoms have resolved. However, in some cases, individuals may require additional treatment for underlying depressive symptoms that may persist independently of substance use. 5. Relapse Risk: There is a risk of relapse if the individual resumes substance use after a period of abstinence, which can lead to a recurrence of depressive symptoms. 6. Treatment: The course can be influenced by treatment interventions. Individuals with Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder may benefit from substance abuse treatment, psychotherapy, and sometimes pharmacotherapy to manage depressive symptoms. Treatment effectiveness can vary depending on individual factors and the specific substance or medication involved. It's important to emphasize that Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder is distinct from primary depressive disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder or Persistent Depressive Disorder. Proper assessment by a mental health professional is essential to differentiate between these conditions. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND COMORBIDITIES Differential diagnosis and comorbidity of Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder involve distinguishing this condition from other mental disorders and recognizing its frequent co-occurrence with substance use disorders. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS 1. Primary Depressive Disorders: One of the key differential diagnoses is differentiating Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder from primary depressive disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD). Clinicians must assess whether the depressive symptoms are primarily due to substance use or medication exposure or whether they represent a separate, independent depressive disorder. 2. Other Substance-Induced Disorders: It's essential to distinguish Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder from other substance-induced disorders, such as Substance-Induced Mood Disorder with Depressive Features. In this case, the depressive symptoms are not severe enough to meet the criteria for a major depressive episode. 3. Medical Conditions: Some medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism, can present with symptoms of depression. A comprehensive medical evaluation should rule out medical causes of depressive symptoms. 4. Other Psychiatric Disorders: Clinicians should consider other psychiatric disorders that may mimic depressive symptoms, such as bipolar disorders, schizoaffective disorder, and adjustment disorders. COMORBIDITY 1. Substance Use Disorders: Substance/MedicationInduced Depressive Disorder often co-occurs with substance use disorders, as the depressive symptoms are induced or exacerbated by substance use. This comorbidity can complicate treatment and recovery. 2. Anxiety Disorders: Individuals with Substance/Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder may also have comorbid anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder. 3. Personality Disorders: There is an increased likelihood of comorbid personality disorders, particularly borderline and antisocial personality disorders, among individuals with substance use disorders and associated depressive symptoms. 4. Other Mental Health Conditions: Depending on the individual's history and circumstances, comorbid mental health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), may be present. TREATMENT APPROACHES The treatment approaches for Substance/MedicationInduced Depressive Disorder primarily focus on addressing both the substance use or medication-related issues and the depressive symptoms. Here are common treatment modalities with references: 1. Substance Use or Medication Intervention: Detoxification: In cases where substance use is the primary cause of depressive symptoms, detoxification and withdrawal management may be necessary to address acute 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. intoxication or withdrawal. This is typically done under medical supervision to ensure safety and minimize discomfort. Substance Abuse Treatment: Following detoxification, individuals may benefit from substance abuse treatment, which can include inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation programs, counseling, and support groups. Behavioral therapies like cognitivebehavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing have shown effectiveness in substance use disorder treatment. Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT): For specific substances, such as opioids or alcohol, medications like methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone may be prescribed in combination with counseling as part of MAT programs. Psychiatric Treatment for Depressive Symptoms: Psychotherapy: Psychotherapeutic interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and dialectical-behavior therapy (DBT), can be beneficial in addressing depressive symptoms. Therapy helps individuals understand the connection between substance use and mood and develop coping strategies. Medication: In some cases, antidepressant medications may be prescribed to alleviate depressive symptoms. The choice of medication depends on the specific symptoms and the individual's response to treatment. SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and other antidepressants are commonly used. Integrated Treatment: Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT): This approach combines mental health and substance use treatment in a coordinated manner. IDDT recognizes the interplay between substance use and mental health disorders and provides comprehensive care. Supportive Interventions: Support Groups: Participation in support groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA), can provide individuals with peer support and a sense of community during their recovery. Relapse Prevention: Relapse Prevention Skills: Individuals are taught coping strategies and relapse prevention skills to help them manage triggers and stressors that might lead to substance use and, subsequently, depressive symptoms. Education and Family Involvement: Psychoeducation: Educating individuals and their families about the relationship between substance use and depressive symptoms, as well as the importance of treatment compliance, can enhance the overall treatment outcome. It's crucial to tailor treatment to the individual's specific needs and circumstances. The effectiveness of treatment can vary based on factors such as the severity of substance use, the duration of depressive symptoms, and the presence of comorbid conditions. DEPRESSIVE DISORDER DUE TO ANOTHER MEDICAL CONDITION Depressive Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition, also known as depressive disorder associated with a medical condition, is a specific type of depressive disorder outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). It occurs when an individual experiences symptoms of depression that can be directly attributed to an underlying medical condition. This depressive disorder occurs when the symptoms of depression are caused by or linked to a medical illness or condition. The medical condition can be either a general medical condition (e.g., cancer, heart disease, diabetes) or a neurological disorder (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease). DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. 1. Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g., feeling sad, empty, hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful). 2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation). 3. Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or a decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day. 5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down). 6. Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day. 7. Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick). 8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others). 9. Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide. B. The individual's depressive symptoms are directly related to the physiological effects of a medical condition. Evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings demonstrates that the disturbance is a consequence of the medical condition. C. The depressive symptoms are not better explained by a primary mental disorder, such as Major Depressive Disorder, and do not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium. D. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. E. The symptoms are not attributable to the psychological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism). F. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of a schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder. It's important to note that the diagnosis of Depressive Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition requires careful evaluation by a qualified healthcare provider, including a thorough assessment of the medical condition causing the depressive symptoms. Reference: American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing. 2. DIAGNOSTIC FEATURE The essential feature of depressive disorder due to another medical condition is a prominent and persistent period of depressed mood or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities that predominates in the clinical picture (Criterion A) and that is thought to be related to the direct physiological effects of another medical condition (Criterion B). In determining whether the mood disturbance is due to a general medical condition, the clinician must first establish the presence of a general medical condition. Further, the clinician must establish that the mood disturbance is etiologically related to the general medical condition through a physiological mechanism. A careful and comprehensive assessment of multiple factors is necessary to make this judgment. Although there are no infallible guidelines for determining whether the relationship between the mood disturbance and the general medical condition is etiological, several considerations provide some guidance in this area. One consideration is the presence of a temporal association between the onset, exacerbation, or remission of the general medical condition and that of the mood disturbance. A second consideration is the presence of features that are atypical of primary Mood Disorders (e.g., atypical age at onset or course or absence of family history). Evidence from the literature that suggests that there can be a direct association between the general medical condition in question and the development of mood symptoms can provide a useful context in the assessment of a particular situation. DEVELOPMENT AND COURSE Depressive disorder due to another medical condition, often referred to as "depression secondary to a medical condition," is a type of depression that occurs as a result of a coexisting medical condition or illness. This condition can significantly impact a person's emotional well-being and overall quality of life. Here is an overview of the development and course of depressive disorder due to another medical condition: 1. Onset and Development: 3. Precipitating Medical Condition: This type of depression typically arises as a response to a pre-existing medical condition. Common medical conditions that can lead to depression include chronic illnesses (e.g., cancer, diabetes, heart disease), neurological disorders (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease), and autoimmune disorders (e.g., lupus). Biological Mechanisms: The exact mechanisms underlying the development of depression in these cases are not fully understood, but it is believed that biological factors, such as changes in neurotransmitter levels, inflammation, and hormonal imbalances, play a role. Symptoms: Individuals with depressive disorder due to another medical condition may experience symptoms similar to major depressive disorder, including persistent sadness, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, changes in appetite or weight, sleep disturbances, fatigue, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, difficulty concentrating, and thoughts of death or suicide. The severity of symptoms can vary depending on the individual, the underlying medical condition, and its progression. Course and Prognosis: The course of depression in the context of a medical condition can be chronic or episodic. Some individuals may experience periods of remission and exacerbation. The prognosis can vary widely, depending on several factors: Severity of the underlying medical condition. Adequacy of treatment for both the medical condition and the depression. Individual resilience and coping skills. Social support system. In some cases, successful management and treatment of the medical condition can lead to improvements in the associated depressive symptoms. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND COMMORBIDITY Differential diagnosis and comorbidity play crucial roles in understanding depressive disorder due to another medical condition. When a person presents with symptoms of depression, it's important for healthcare providers to differentiate between depression that arises as a result of an underlying medical condition and depression that occurs independently. Here's an overview of the differential diagnosis and comorbidity associated with depressive disorder due to another medical condition: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: Distinguishing between depressive disorder due to another medical condition and primary depressive disorders (such as major depressive disorder) is essential because the treatment approach may differ. Here are some key considerations in the differential diagnosis: Medical Condition Assessment: Healthcare providers must thoroughly evaluate the patient's medical history, perform a physical examination, and conduct appropriate diagnostic tests to identify and assess the severity of any underlying medical conditions. The presence of a medical condition and its impact on the patient's mental health is a critical factor. Symptom Profile: Clinicians carefully assess the symptoms to determine whether they are primarily related to the medical condition, the depression, or a combination of both. For example, somatic symptoms (physical complaints) may be more pronounced in depressive disorder due to another medical condition. Temporal Relationship: Understanding the timing of symptom onset is important. Depressive symptoms that coincide with the onset or exacerbation of a medical condition may suggest a causal relationship. Response to Treatment: Response to treatment can also provide diagnostic information. If depressive symptoms significantly improve when the underlying medical condition is effectively managed or treated, it suggests a secondary depression. Substance Use Disorders: Some individuals may turn to alcohol or drugs as a way to cope with their depression, leading to substance use disorders. Cognitive Impairment: Cognitive impairment, including problems with memory and concentration, can be a feature of both depression and certain medical conditions. Suicidal Ideation: Individuals with depressive disorder due to another medical condition may be at an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, especially when coping with both physical illness and depression. Impaired Functioning: Depression can lead to impaired social, occupational, and functional abilities, which can further worsen the impact of the underlying medical condition. Comorbidity underscores the importance of a comprehensive assessment and treatment plan. Healthcare providers need to address not only the depressive symptoms but also any coexisting medical or psychological conditions to provide holistic care for the patient's well-being. TREAMENT APPROACHES The treatment of depressive disorder due to another medical condition involves a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach. The primary goal is to alleviate depressive symptoms while also addressing and managing the underlying medical condition. Here are the key treatment approaches: 1. Exclusion of Primary Depressive Disorder: Clinicians must exclude the possibility of primary depressive disorders, which can occur independently of medical conditions. These include major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), and bipolar disorder. COMORBIDITY: Comorbidity refers to the co-occurrence of multiple medical or psychological conditions in the same individual. In the case of depressive disorder due to another medical condition, comorbidity is common and can significantly impact a person's overall health and well-being. Here are some common comorbidities associated with this type of depression: 2. Anxiety Disorders: Individuals with depressive disorder due to another medical condition may also experience anxiety disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or social anxiety disorder. Pain Syndromes: Many medical conditions associated with depression can also cause chronic pain syndromes. These include conditions like fibromyalgia, arthritis, or chronic headaches. Sleep Disorders: Sleep disturbances are common in depression and can further exacerbate depressive symptoms. Conditions like insomnia or sleep apnea may co-occur. 3. Medical Management of the Underlying Condition: Effectively managing the medical condition that is contributing to the depressive symptoms is of paramount importance. This may involve surgery, medications, physical therapy, lifestyle modifications, or other appropriate treatments. Stabilizing the underlying condition can sometimes lead to an improvement in depressive symptoms. Psychotherapy (Talk Therapy): Psychotherapy is a crucial component of treatment for depressive disorder due to another medical condition. Cognitivebehavioral therapy (CBT), supportive therapy, and problem-solving therapy are often used. Psychotherapy helps individuals address the emotional and psychological impact of both the medical condition and the depression, teaches coping strategies, and promotes resilience. Medication: Antidepressant medications may be prescribed to alleviate depressive symptoms. The choice of medication depends on factors such as the type and severity of depression, the individual's medical condition, and potential drug interactions. Careful monitoring is essential, as some medications may have side effects or interactions with medications used to treat the underlying medical condition. 4. Integrated Care Teams: A coordinated healthcare team, including primary care physicians, specialists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, is often necessary to ensure comprehensive care. Regular communication and collaboration among team members help in tailoring treatment plans to individual needs. 5. Social Support: Building a strong support network is vital. Friends and family members can provide emotional support, assistance with daily activities, and encouragement during the treatment process. Support groups for individuals facing similar medical conditions or mental health challenges can also be beneficial. 6. Lifestyle Modifications: Encouraging a healthy lifestyle can have a positive impact on both the medical condition and depression. This includes regular exercise, a balanced diet, adequate sleep, and stress reduction techniques. Avoiding alcohol and substance abuse is essential, as these can worsen both the medical condition and depressive symptoms. 7. Stress Management: Learning stress management techniques, such as relaxation exercises, mindfulness, and meditation, can help individuals better cope with the challenges of managing a medical condition and depression. 8. Education and Self-Management: Providing patients and their families with information about the medical condition and depressive disorder can empower them to actively participate in their care and make informed decisions. 9. Regular Monitoring and Follow-Up: Continuous monitoring of both the medical condition and depressive symptoms is crucial. Treatment plans may need to be adjusted over time based on the individual's progress and changing needs. 10. Suicide Risk Assessment and Prevention: Assessing and addressing suicidal thoughts or behaviors is a critical aspect of care, especially in cases of severe depression. 11. Crisis Intervention: In emergency situations or when there is a risk of harm to oneself or others, immediate crisis intervention and hospitalization may be necessary. It's important to note that the specific treatment plan will vary depending on the individual's unique circumstances, the severity of the medical condition, and the nature of the depressive symptoms. Treatment should be tailored to address both the physical and mental health aspects of the individual's well-being. Close collaboration between healthcare providers, specialists, and mental health professionals is essential for the best outcomes. OTHER SPECIFIED DEPRESSIVE DISORDER This category applies to presentations in which symptoms characteristic of a depressive disorder that cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning predominate but do not meet the full criteria for any of the disorders in the depressive disorders diagnostic class. The other specified depressive disorder category is used in situations in which the clinician chooses to communicate the specific reason that the presentation does not meet the criteria for any specific depressive disorder. This is done by recording “other specified depressive disorder” followed by the specific reason (e.g., “short-duration depressive episode”). Examples of presentations that can be specified using the “other specified” designation include the following: 1. Recurrent brief depression: Concurrent presence of depressed mood and at least four other symptoms of depression for 2-13 days at least once per month (not associated with the menstrual cycle) for at least 12 consecutive months in an individual whose presentation has never met criteria for any other depressive or bipolar disorder and does not currently meet active or residual criteria for any psychotic disorder. 2. Short-duration depressive episode (4-13 days): Depressed affect and at least four of the other eight symptoms of a major depressive episode associated with clinically significant distress or impairment that persists for more than 4 days, but less than 14 days, in an individual whose presentation has never met criteria for any other depressive or bipolar disorder, does not currently meet active or residual criteria for any psychotic disorder, and does not meet criteria for recurrent brief depression. 3. Depressive episode with insufficient symptoms: Depressed affect and at least one of the other eight symptoms of a major depressive episode associated with clinically significant distress or impairment tliat persist for at least 2 weeks in an individual whose presentation has never met criteria for any other depressive or bipolar disorder, does not currently meet active or residual criteria for any psychotic disorder, and does not meet criteria for mixed anxiety and depressive disorder symptoms. UNSPECIFIED DEPRESSIVE DISORDER This category applies to presentations in which symptoms characteristic of a depressive disorder that cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning predominate but do not meet the full criteria for any of the disorders in the depressive disorders diagnostic class. The unspecified depressive disorder category is used in situations in which the clinician chooses not to specify the reason that the criteria are not met for a specific depressive disorder, and includes presentations for which there is insufficient information to make a more specific diagnosis (e.g., in emergency room settings). SPECIFIERS FOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER In the diagnosis of depressive disorders, clinicians often use specifiers to provide additional information about the nature and course of the depressive episode. Specifiers help in describing the specific features and characteristics of the depression, which can be important for treatment planning and understanding the patient's condition. Here are some common specifiers used for depressive disorders: 1. Severity Specifiers: Severity specifiers are used to classify the severity of a depressive episode based on the number and intensity of symptoms. The two main severity specifiers are: Mild: Few, if any, symptoms beyond the minimum required for diagnosis, and the symptoms result in only minor impairment in daily functioning. Moderate: Symptoms are more numerous or intense than in mild depression, and they result in moderate impairment in daily functioning. Severe: Symptoms are highly distressing and significantly impact daily functioning. In severe depression, there may be psychotic features (e.g., hallucinations or delusions) or a risk of self-harm or suicide. 2. Psychotic Features: Some individuals with depressive disorder may experience psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations (false sensory perceptions) or delusions (strongly held false beliefs). This specifier is used when these features are present. 3. Anxious Distress: This specifier is used when the individual with depression also experiences prominent anxiety symptoms, such as excessive worry, restlessness, or a feeling of inner tension. 4. Atypical Features: Atypical features include mood reactivity (the ability to experience improved mood in response to positive events), increased appetite or weight gain, hypersomnia (excessive sleepiness), leaden paralysis (a heavy, leaden feeling in the limbs), and longstanding interpersonal rejection sensitivity. 5. Melancholic Features: This specifier is used when the individual experiences a more severe and classic form of depression. Features may include profound loss of pleasure in almost all activities (anhedonia), excessive guilt, early morning awakening, and marked psychomotor retardation or agitation. 6. Catatonia: Catatonia is a severe psychomotor disturbance that can occur in the context of depression. It involves a range of symptoms, such as stupor (motionless and unresponsive), mutism (inability or refusal to speak), negativism (oppositional behavior), rigidity, and other unusual motor behaviors. 7. Peripartum Onset (Postpartum Depression): This specifier is used when the onset of a depressive episode occurs during pregnancy or within four weeks after giving birth. Postpartum depression is a specific subtype of depressive disorder that affects some new mothers. 8. Seasonal Pattern (Seasonal Affective Disorder): Seasonal pattern specifier is used when an individual's depressive episodes consistently occur at specific times of the year, typically in the fall or winter, and remit in the spring or summer. 9. Chronic: This specifier indicates that the depressive episode has lasted for two years or more without a significant period of remission. This condition is known as Persistent Depressive Disorder (formerly called Dysthymia). 10. In Partial Remission or Full Remission: These specifiers are used to describe the course of the depressive episode. Partial remission indicates that some symptoms persist but are less severe, while full remission means that no significant symptoms are present. These specifiers help clinicians better characterize and understand the specific features of a person's depressive episode. They can also guide treatment decisions, as certain specifiers may indicate the need for specific interventions or approaches. It's important for mental health professionals to carefully assess and document these specifiers to provide the most appropriate care for individuals with depressive disorders.