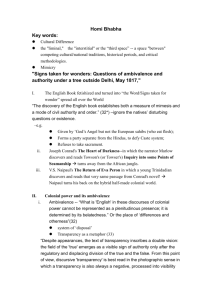

Emigrant Identity Crisis: Ambivalence in Postcolonial Literature

advertisement