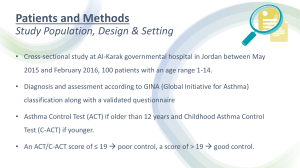

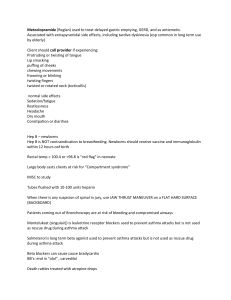

Asthma Diagnosis & Management: Philippine Consensus Report 2019

advertisement