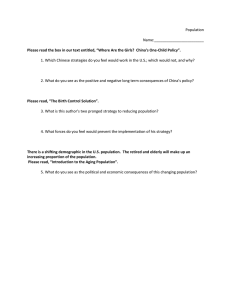

Parental Gender Expectations in China: An Intersectional Analysis

advertisement