should receive one of those diagnoses rather than disruptive mood dysregulation disor­

der. Children with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder may have symptoms that also

meet criteria for an anxiety disorder and can receive both diagnoses, but children whose ir­

ritability is manifest only in the context of exacerbation of an anxiety disorder should re­

ceive the relevant anxiety disorder diagnosis rather than disruptive mood dysregulation

disorder. In addition, children with autism spectrum disorders frequently present with

temper outbursts when, for example, their routines are disturbed. In that instance, the

temper outbursts would be considered secondary to the autism spectrum disorder, and

the child should not receive the diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

Intermittent explosive disorder. Children with symptoms suggestive of intermittent

explosive disorder present with instances of severe temper outbursts, much like children

with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. However, unlike disruptive mood dysreg­

ulation disorder, intermittent explosive disorder does not require persistent disruption in

mood between outbursts. In addition, intermittent explosive disorder requires only 3 months

of active symptoms, in contrast to the 12-month requirement for disruptive mood dys­

regulation disorder. Thus, these two diagnoses should not be made in the same child. For

children with outbursts and intercurrent, persistent irritability, only the diagnosis of dis­

ruptive mood dysregulation disorder should be made.

Comorbidity

Rates of comorbidity in disruptive mood dysregulation disorder are extremely high. It is

rare to find individuals whose symptoms meet criteria for disruptive mood dysregulation

disorder alone. Comorbidity between disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and other

DSM-defined syndromes appears higher than for many other pediatric mental illnesses;

the strongest overlap is with oppositional defiant disorder. Not only is the overall rate of

comorbidity high in disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, but also the range of comorbid illnesses appears particularly diverse. These children typically present to the clinic

with a wide range of disruptive behavior, mood, anxiety, and even autism spectrum

symptoms and diagnoses. However, children with disruptive mood dysregulation disor­

der should not have symptoms that meet criteria for bipolar disorder, as in that context,

only the bipolar disorder diagnosis should be made. If children have symptoms that meet

criteria for oppositional defiant disorder or intermittent explosive disorder and disruptive

mood dysregulation disorder, only the diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disor­

der should be assigned. Also, as noted earlier, the diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregu­

lation disorder should not be assigned if the symptoms occur only in an anxietyprovoking context, when the routines of a child with autism spectrum disorder or obses­

sive-compulsive disorder are disturbed, or in the context of a major depressive episode.

Major Depressive Disorder

Diagnostic Criteria

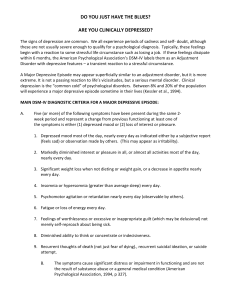

A. Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week

period and represent a change from previous functioning: at least one of the symptoms

is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

Note: Do not include symptoms that are clearly attributable to another medical condition.

1. Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjec­

tive report (e.g., feels sad, empty, hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g.,

appears tearful). (Note: In children and adolescents, can be irritable mood.)

2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the

day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation).

3. Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than

5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day.

(Note: In children, consider failure to make expected weight gain.)

4. Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not

merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down).

6. Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

7. Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delu­

sional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick).

8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (ei­

ther by subjective account or as observed by others).

9. Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation with­

out a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide.

B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupa­

tional, or other important areas of functioning.

C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or to another

medical condition.

Note: Criteria A-C represent a major depressive episode.

Note: Responses to a significant loss (e.g., bereavement, financial ruin, losses from a nat­

ural disaster, a serious medical illness or disability) may include the feelings of intense sad­

ness, rumination about the loss, insomnia, poor appetite, and weight loss noted in Criterion A,

which may resemble a depressive episode. Although such symptoms may be understand­

able or considered appropriate to the loss, the presence of a major depressive episode in

addition to the normal response to a significant loss should also be carefully considered. This

decision inevitably requires the exercise of clinical judgment based on the individual’s history

and the cultural norms for the expression of distress in the context of loss.^

D. The occurrence of the major depressive episode is not better explained by schizoaf­

fective disorder, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or

other specified and unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders.

E. There has never been a manic episode or a hypomanie episode.

Note: This exclusion does not apply if all of the manic-like or hypomanic-like episodes

are substance-induced or are attributable to the physiological effects of another med­

ical condition.

’ In distinguishing grief from a major depressive episode (MDE), it is useful to consider that in

grief the predominant affect is feelings of emptiness and loss, while in MDE it is persistent

depressed mood and the inability to anticipate happiness or pleasure. The dysphoria in grief is

likely to decrease in intensity over days to weeks and occurs in waves, the so-called pangs of

grief. These waves tend to be associated with thoughts or reminders of the deceased. The

depressed mood of MDE is more persistent and not tied to specific thoughts or preoccupations.

The pain of grief may be accompanied by positive emotions and humor that are uncharacteristic

of the pervasive unhappiness and misery characteristic of MDE. The thought content associated

with grief generally features a preoccupation with thoughts and memories of the deceased,

rather than the self-critical or pessimistic ruminations seen in MDE. In grief, self-esteem is gener­

ally preserved, whereas in MDE feelings of worthlessness and self-loathing are common. If self­

derogatory ideation is present in grief, it typically involves perceived failings vis-à-vis the

deceased (e.g., not visiting frequently enough, not telling the deceased how much he or she was

loved). If a bereaved individual thinks about death and dying, such thoughts are generally

focused on the deceased and possibly about "joining" the deceased, whereas in MDE such

thoughts are focused on ending one's own life because of feeling worthless, undeserving of life,

or unable to cope with the pain of depression.

Coding and Recording Procedures

The diagnostic code for major depressive disorder is based on whether this is a single or

recurrent episode, current severity, presence of psychotic features, and remission status.

Current severity and psychotic features are only indicated if full criteria are currently met

for a major depressive episode. Remission specifiers are only indicated if the full criteria

are not currently met for a major depressive episode. Codes are as follows:

Severity/course specifier

Single episode

Recurrent episode*

Mild (p. 188)

296.21 (F32.0)

296.31 (F33.0)

Moderate (p. 188)

296.22 (F32.1)

296.32 (F33.1)

Severe (p. 188)

296.23 (F32.2)

296.33 (F33.2)

With psychotic features** (p. 186)

296.24 (F32.3)

296.34 (F33.3)

In partial remission (p. 188)

296.25 (F32.4)

296.35 (F33.41)

In full remission (p. 188)

296.26 (F32.5)

296.36 (F33.42)

Unspecified

296.20 (F32.9)

296.30 (F33.9)

*For an episode to be considered recurrent, there must be an interval of at least 2 consecutive months

between separate episodes in which criteria are not met for a major depressive episode. The defini­

tions of specifiers are found on the indicated pages.

**If psychotic features are present, code the "with psychotic features" specifier irrespective of epi­

sode severity.

In recording the name of a diagnosis, terms should be listed in the following order: major

depressive disorder, single or recurrent episode, severity/psychotic/remission specifiers,

followed by as many of the following specifiers without codes that apply to the current

episode.

Specify:

With

With

With

With

With

anxious distress (p. 184)

mixed features (pp. 184-185)

melancholic features (p. 185)

atypical features (pp. 185-186)

mood-congruent psychotic features (p. 186)

With mood-incongruent psychotic features (p. 186)

With catatonia (p. 186). Coding note: Use additional code 293.89 (F06.1).

With péripartum onset (pp. 186-187)

With seasonal pattern (recurrent episode only) (pp. 187-188)

Diagnostic Features

The criterion symptoms for major depressive disorder must be present nearly every day to

be considered present, with the exception of weight change and suicidal ideation. De­

pressed mood must be present for most of the day, in addition to being present nearly ev­

ery day. Often insomnia or fatigue is the presenting complaint, and failure to probe for

accompanying depressive symptoms will result in underdiagnosis. Sadness may be de­

nied at first but may be elicited through interview or inferred from facial expression and

demeanor. With individuals who focus on a somatic complaint, clinicians should de­

termine whether the distress from that complaint is associated with specific depressive

symptoms. Fatigue and sleep disturbance are present in a high proportion of cases; psy­

chomotor disturbances are much less common but are indicative of greater overall sever­

ity, as is the presence of delusional or near-delusional guilt.

The essential feature of a major depressive episode is a period of at least 2 weeks during

w^hich there is either depressed mood or the loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activi­

ties (Criterion A). In children and adolescents, the mood may be irritable rather than sad.

The individual must also experience at least four additional symptoms drawn from a list

that includes changes in appetite or weight, sleep, and psychomotor activity; decreased en­

ergy; feelings of worthlessness or guilt; difficulty thinking, concentrating, or making deci­

sions; or recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation or suicide plans or attempts. To

count toward a major depressive episode, a symptom must either be newly present or must

have clearly worsened compared with the person's pre-episode status. The symptoms

must persist for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 consecutive weeks. The ep­

isode must be accompanied by clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occu­

pational, or other important areas of functioning. For some individuals with milder

episodes, functioning may appear to be normal but requires markedly increased effort.

The mood in a major depressive episode is often described by the person as depressed,

sad, hopeless, discouraged, or "down in the dumps" (Criterion Al). In some cases, sadness

may be denied at first but may subsequently be elicited by interview (e.g., by pointing out

that the individual looks as if he or she is about to cry). In some individuals who complain

of feeling "blah," having no feelings, or feeling anxious, the presence of a depressed mood

can be inferred from the person's facial expression and demeanor. Some individuals em­

phasize somatic complaints (e.g., bodily aches and pains) rather than reporting feelings of

sadness. Many individuals report or exhibit increased irritability (e.g., persistent anger, a

tendency to respond to events with angry outbursts or blaming others, an exaggerated

sense of frustration over minor matters). In children and adolescents, an irritable or cranky

mood may develop rather than a sad or dejected mood. This presentation should be dif­

ferentiated from a pattern of irritability when frustrated.

Loss of interest or pleasure is nearly always present, at least to some degree. Individ­

uals may report feeling less interested in hobbies, "not caring anymore," or not feeling any

enjoyment in activities that were previously considered pleasurable (Criterion A2). Family

members often notice social withdrawal or neglect of pleasurable avocations (e.g., a for­

merly avid golfer no longer plays, a child who used to enjoy soccer finds excuses not to

practice). In some individuals, there is a significant reduction from previous levels of sex­

ual interest or desire.

Appetite change may involve either a reduction or increase. Some depressed individ­

uals report that they have to force themselves to eat. Others may eat more and may crave

specific foods (e.g., sweets or other carbohydrates). When appetite changes are severe (in

either direction), there may be a significant loss or gain in weight, or, in children, a failure

to make expected weight gains may be noted (Criterion A3).

Sleep disturbance may take the form of either difficulty sleeping or sleeping exces­

sively (Criterion A4). When insomnia is present, it typically takes the form of middle insonrmia (i.e., waking up during the night and then having difficulty returning to sleep) or

terminal insomnia (i.e., waking too early and being unable to return to sleep). Initial in­

somnia (i.e., difficulty falling asleep) may also occur. Individuals who present with over­

sleeping (hypersomnia) may experience prolonged sleep episodes at night or increased

daytime sleep. Sometimes the reason that the individual seeks treatment is for the dis­

turbed sleep.

Psychomotor changes include agitation (e.g., the inability to sit still, pacing, handwringing; or pulling or rubbing of the skin, clothing, or other objects) or retardation (e.g.,

slowed speech, thinking, and body movements; increased pauses before answering;

speech that is decreased in volume, inflection, amount, or variety of content, or muteness)

(Criterion A5). The psychomotor agitation or retardation must be severe enough to be ob­

servable by others and not represent merely subjective feelings.

Decreased energy, tiredness, and fatigue are common (Criterion A6). A person may re­

port sustained fatigue without physical exertion. Even the smallest tasks seem to require

substantial effort. The efficiency with which tasks are accomplished may be reduced. For

example, an individual may complain that washing and dressing in the morning are ex­

hausting and take twice as long as usual.

The sense of worthlessness or guilt associated with a major depressive episode may in­

clude unrealistic negative evaluations of one's worth or guilty preoccupations or rumina­

tions over minor past failings (Criterion A7). Such individuals often misinterpret neutral

or trivial day-to-day events as evidence of personal defects and have an exaggerated sense

of responsibility for untoward events. The sense of worthlessness or guilt may be of delu­

sional proportions (e.g., an individual who is convinced that he or she is personally re­

sponsible for world poverty). Blaming oneself for being sick and for failing to meet

occupational or inteφersonal responsibilities as a result of the depression is very common

and, unless delusional, is not considered sufficient to meet this criterion.

Many individuals report impaired ability to think, concentrate, or make even minor

decisions (Criterion A8). They may appear easily distracted or complain of memory diffi­

culties. Those engaged in cognitively demanding pursuits are often unable to function. In

children, a precipitous drop in grades may reflect poor concentration. In elderly individ­

uals, memory difficulties may be the chief complaint and may be mistaken for early signs

of a dementia (''pseudodementia"). When the major depressive episode is successfully

treated, the memory problems often fully abate. However, in some individuals, particu­

larly elderly persons, a major depressive episode may sometimes be the initial presenta­

tion of an irreversible dementia.

Thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts (Criterion A9) are common.

They may range from a passive wish not to awaken in the morning or a belief that others

would be better off if the individual were dead, to transient but recurrent thoughts of com­

mitting suicide, to a specific suicide plan. More severely suicidal individuals may have put

their affairs in order (e.g., updated wills, settled debts), acquired needed materials (e.g., a

rope or a gun), and chosen a location and time to accomplish the suicide. Motivations for

suicide may include a desire to give up in the face of perceived insurmountable obstacles,

an intense wish to end what is perceived as an unending and excruciatingly painful emo­

tional state, an inability to foresee any enjoyment in life, or the wish to not be a burden to

others. The resolution of such thinking may be a more meaningful measure of diminished

suicide risk than denial of further plans for suicide.

The evaluation of the symptoms of a major depressive episode is especially difficult

when they occur in an individual who also has a general medical condition (e.g., cancer,

stroke, myocardial infarction, diabetes, pregnancy). Some of the criterion signs and symp­

toms of a major depressive episode are identical to those of general medical conditions

(e.g., weight loss with untreated diabetes; fatigue with cancer; hypersomnia early in preg­

nancy; insonmia later in pregnancy or the postpartum). Such symptoms count toward a

major depressive diagnosis except when they are clearly and fully attributable to a general

medical condition. Nonvegetative symptoms of dysphoria, anhedonia, guilt or worthless­

ness, impaired concentration or indecision, and suicidal thoughts should be assessed with

particular care in such cases. Definitions of major depressive episodes that have been mod­

ified to include only these nonvegetative symptoms appear to identify nearly the same in­

dividuals as do the full criteria.

Associated Features Supporting Diagnosis

Major depressive disorder is associated with high mortality, much of which is accounted

for by suicide; however, it is not the only cause. For example, depressed individuals ad­

mitted to nursing homes have a markedly increased likelihood of death in the first year. In­

dividuals frequently present with tearfulness, irritability, brooding, obsessive rumination,

anxiety, phobias, excessive worry over physical health, and complaints of pain (e.g., head­

aches; joint, abdominal, or other pains). In children, separation anxiety may occur.

Although an extensive literature exists describing neuroanatomical, neuroendocrino­

logical, and neurophysiological correlates of major depressive disorder, no laboratory test

has yielded results of sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be used as a diagnostic tool for

this disorder. Until recently, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivity had been

the most extensively investigated abnormality associated v^ith major depressive episodes,

and it appears to be associated with melancholia, psychotic features, and risks for eventual

suicide. Molecular studies have also implicated peripheral factors, including genetic vari­

ants in neurotrophic factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, functional

magnetic resonance imaging studies provide evidence for functional abnormalities in spe­

cific neural systems supporting emotion processing, reward seeking, and emotion regula­

tion in adults with major depression.

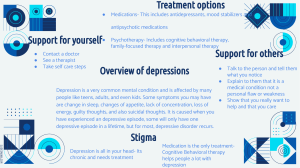

Prevalence

Twelve-month prevalence of major depressive disorder in the United States is approximately

7%, with marked differences by age group such that the prevalence in 18- to 29-year-old indi­

viduals is threefold higher than the prevalence in individuals age 60 years or older. Females ex­

perience 1.5- to 3-fold higher rates than males beginning in early adolescence.

Development and Course

Major depressive disorder may first appear at any age, but the likelihood of onset in­

creases markedly with puberty. In the United States, incidence appears to peak in the 20s;

however, first onset in late life is not uncommon.

The course of major depressive disorder is quite variable, such that some individuals

rarely, if ever, experience remission (a period of 2 or more months with no symptoms, or

only one or two symptoms to no more than a mild degree), while others experience many

years with few or no symptoms between discrete episodes. It is important to distinguish

individuals who present for treatment during an exacerbation of a chronic depressive ill­

ness from those whose symptoms developed recently. Chronicity of depressive symptoms

substantially increases the likelihood of underlying personality, anxiety, and substance

use disorders and decreases the likelihood that treatment will be followed by full symp­

tom resolution. It is therefore useful to ask individuals presenting with depressive symp­

toms to identify the last period of at least 2 months during which they were entirely free of

depressive symptoms.

Recovery typically begins within 3 months of onset for two in five individuals with ma­

jor depression and within 1 year for four in five individuals. Recency of onset is a strong

determinant of the likelihood of near-term recovery, and many individuals who have been

depressed only for several months can be expected to recover spontaneously. Features as­

sociated with lower recovery rates, other than current episode duration, include psychotic

features, prominent anxiety, personality disorders, and symptom severity.

The risk of recurrence becomes progessively lower over time as the duration of re­

mission increases. The risk is higher in individuals whose preceding episode was severe,

in younger individuals, and in individuals who have already experienced multiple epi­

sodes. The persistence of even mild depressive symptoms during remission is a powerful

predictor of recurrence.

Many bipolar illnesses begin with one or more depressive episodes, and a substantial

proportion of individuals who initially appear to have major depressive disorder will

prove, in time, to instead have a bipolar disorder. This is more likely in individuals with

onset of the illness in adolescence, those with psychotic features, and those with a family

history of bipolar illness. The presence of a "'with mixed features" specifier also increases

the risk for future manic or hypomanie diagnosis. Major depressive disorder, particularly

with psychotic features, may also transition into schizophrenia, a change that is much

more frequent than the reverse.

Despite consistent differences between genders in prevalence rates for depressive disor­

ders, there appear to be no clear differences by gender in phenomenology, course, or treat­

ment response. Similarly, there are no clear effects of current age on the course or treatment

response of major depressive disorder. Some symptom differences exist, though, such that

hypersomnia and hyperphagia are more likely in younger individuals, and melancholic

symptoms, particularly psychomotor disturbances, are more common in older individuals.

The likelihood of suicide attempts lessens in middle and late life, although the risk of com­

pleted suicide does not. Depressions with earlier ages at onset are more familial and more

likely to involve personality disturbances. The course of major depressive disorder within

individuals does not generally change with aging. Mean times to recovery appear to be sta­

ble over long periods, and the likelihood of being in an episode does not generally increase

or decrease with time.

Risk and Prognostic Factors

Temperamental. Neuroticism (negative affectivity) is a well-established risk factor for the

onset of major depressive disorder, and high levels appear to render individuals more likely

to develop depressive episodes in response to stressful life events.

Environmental. Adverse childhood experiences, particularly when there are multiple

experiences of diverse types, constitute a set of potent risk factors for major depressive dis­

order. Stressful life events are well recognized as précipitants of major depressive epi­

sodes, but the presence or absence of adverse life events near the onset of episodes does

not appear to provide a useful guide to prognosis or treatment selection.

Genetic and physiological. First-degree family members of individuals with major de­

pressive disorder have a risk for major depressive disorder two- to fourfold higher than

that of the general population. Relative risks appear to be higher for early-onset and re­

current forms. Heritability is approximately 40%, and the personality trait neuroticism ac­

counts for a substantial portion of this genetic liability.

Course modifiers. Essentially all major nonmood disorders increase the risk of an indi­

vidual developing depression. Major depressive episodes that develop against the back­

ground of another disorder often follow a more refractory course. Substance use, anxiety,

and borderline personality disorders are among the most common of these, and the pre­

senting depressive symptoms may obscure and delay their recognition. However, sus­

tained clinical improvement in depressive symptoms may depend on the appropriate

treatment of underlying illnesses. Chronic or disabling medical conditions also increase

risks for major depressive episodes. Such prevalent illnesses as diabetes, morbid obesity,

and cardiovascular disease are often complicated by depressive episodes, and these epi­

sodes are more likely to become chronic than are depressive episodes in medically healthy

individuals.

Cuiture-Reiated Diagnostic issues

Surveys of major depressive disorder across diverse cultures have shown sevenfold dif­

ferences in 12-month prevalence rates but much more consistency in female-to-male raho,

mean ages at onset, and the degree to which presence of the disorder raises the likelihood

of comorbid substance abuse. While these findings suggest substantial cultural differences

in the expression of major depressive disorder, they do not permit simple linkages be­

tween particular cultures and the likelihood of specific symptoms. Rather, clinicians

should be aware that in most countries the majority of cases of depression go unrecog­

nized in primary care settings and that in many cultures, somatic symptoms are very likely

to constitute the presenting complaint. Among the Criterion A symptoms, insomnia and

loss of energy are the most uniformly reported.

Gender-Related Diagnostic issues

Although the möst reproducible finding in the epidemiology of major depressive disorder

has been a higher prevalence in females, there are no clear differences between genders in

symptoms, course, treatment response, or functional consequences. In w^omen, the risk for

suicide attempts is higher, and the risk for suicide completion is lower. The disparity in

suicide rate by gender is not as great among those with depressive disorders as it is in the

population as a whole.

Suicide Risic

The possibility of suicidal behavior exists at all times during major depressive episodes.

The most consistently described risk factor is a past history of suicide attempts or threats,

but it should be remembered that most completed suicides are not preceded by unsuccess­

ful attempts. Other features associated with an increased risk for completed suicide

include male sex, being single or living alone, and having prominent feelings of hopeless­

ness. The presence of borderline personality disorder markedly increases risk for future

suicide attempts.

Functional Consequences of

iVlajor Depressive Disorder

Many of the functional consequences of major depressive disorder derive from individual

symptoms. Impairment can be very mild, such that many of those who interact with the af­

fected individual are unaware of depressive symptoms. Impairment may, however, range

to complete incapacity such that the depressed individual is unable to attend to basic self­

care needs or is mute or catatonic. Among individuals seen in general medical settings,

those with major depressive disorder have more pain and physical illness and greater de­

creases in physical, social, and role functioning.

Differential Diagnosis

Manic episodes with irritable mood or mixed episodes. Major depressive episodes

with prominent irritable mood may be difficult to distinguish from manic episodes with

irritable mood or from mixed episodes. This distinction requires a careful clinical evalua­

tion of the presence of manic symptoms.

Mood disorder due to another medical condition. A major depressive episode is the

appropriate diagnosis if the mood disturbance is not judged, based on individual history,

physical examination, and laboratory findings, to be the direct pathophysiological conse­

quence of a specific medical condition (e.g., multiple sclerosis, stroke, hypothyroidism).

Substance/medication-induced depressive or bipolar disorder. This disorder is distin­

guished from major depressive disorder by the fact that a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse,

a medication, a toxin) appears to be etiologically related to the mood disturbance. For ex­

ample, depressed mood that occurs only in the context of withdrawal from cocaine would

be diagnosed as cocaine-induced depressive disorder.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Distractibility and low frustration tolerance

can occur in both attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and a major depressive epi­

sode; if the criteria are met for both, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder may be diag­

nosed in addition to the mood disorder. However, the clinician must be cautious not to

overdiagnose a major depressive episode in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder whose disturbance in mood is characterized by irritability rather than by sadness

or loss of interest.

Adjustment disorder with depressed mood. A major depressive episode that occurs in

response to a psychosocial stressor is distinguished from adjustment disorder w^ith de­

pressed mood by the fact that the full criteria for a major depressive episode are not met in

adjustment disorder.

Sadness. Finally, periods of sadness are inherent aspects of the human experience.

These periods should not be diagnosed as a major depressive episode unless criteria are

met for severity (i.e., five out of nine symptoms), duration (i.e., most of the day, nearly ev­

ery day for at least 2 w^eeks), and clinically significant distress or impairment. The diagno­

sis other specified depressive disorder may be appropriate for presentations of depressed

mood wiih clinically significant impairment that do not meet criteria for duration or se­

verity.

Comorbidity

Other disorders with which major depressive disorder frequently co-occurs are substancerelated disorders, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, buli­

mia nervosa, and borderline personality disorder.

Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia)

Diagnostic Criteria

300.4 (F34.1)

This disorder represents a consolidation of DSM-lV-defined chronic major depressive dis­

order and dysthymic disorder.

A. Depressed mood for most of the day, for more days than not, as indicated by either

subjective account or observation by others, for at least 2 years.

Note: In children and adolescents, mood can be irritable and duration must be at least

1 year.

B. Presence, while depressed, of two (or more) of the following:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Poor appetite or overeating.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Low energy or fatigue.

Low self-esteem.

Poor concentration or difficulty making decisions.

Feelings of hopelessness.

C. During the 2-year period (1 year for children or adolescents) of the disturbance, the individ­

ual has never been without the symptoms in Criteria A and B for more than 2 months at a

time.

D. Criteria for a major depressive disorder may be continuously present for 2 years.

E. There has never been a manic episode or a hypomanie episode, and criteria have

never been met for cyclothymic disorder.

F. The disturbance is not better explained by a persistent schizoaffective disorder,

schizophrenia, delusional disorder, or other specified or unspecified schizophrenia

spectrum and other psychotic disorder.

G. The symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a

drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g. hypothyroidism).

H. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational,

or other important areas of functioning.

Note: Because the criteria for a major depressive episode include four symptoms that are

absent from the symptom list for persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), a very limited