Drone Tech & Entrepreneurship: Co-evolution in the Drone Industry

advertisement

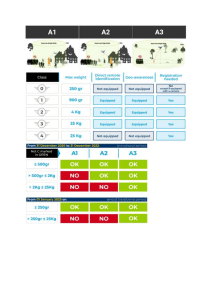

Business Horizons (2017) 60, 875—884 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor From toys to tools: The co-evolution of technological and entrepreneurial developments in the drone industry Ferran Giones a,*, Alexander Brem a,b a b Mads Clausen Institute, University of Southern Denmark, Alsion 2, Sønderborg 6400, Denmark Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nuremberg, Germany KEYWORDS Technological progress; Entrepreneurial activity; Drones; Drone industry; Emerging industries; Unmanned aircraft systems; Unmanned aerial vehicles; Drone development Abstract There is undoubtedly hype around drones and their applications for private and professional users. Based on a brief overview of the development of the drone industry in recent years, this article examines the co-evolution of drone technology and the entrepreneurial activity linked to it. Our results highlight the industry emergence described as concept validation, including product as well as market growth with different phases of technological meaning change. We argue that further steps are needed to develop drones from nice toys to professional tools–—from photography and filming applications to inspection services and large cargo logistics. For innovation managers and entrepreneurs, we describe what triggers the emergence of a technology and attracts the needed actors to unleash its transformative potential. Our research is based on industry reports, news, and market studies as well as interviews with four industry actors. # 2017 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Drone technology: A new opportunity? Technological innovations open opportunities for new entrants to transform and recreate industries, creating disruption known as ‘innovation shocks.’ This term is used by Argyres, Bigelow, and Nickerson (2015, p. 219) “as the introduction by a firm of a * Corresponding author E-mail addresses: fgiones@mci.sdu.dk (F. Giones), alexander.brem@fau.de (A. Brem) new product that stimulates a substantial surge and acceleration in demand for that product–—a surge that was generally unexpected by market participants.” However, understanding and predicting the evolution of such emerging technologies is a challenge for new entrants as well as for incumbents (Dedehayir & Steinert, 2016). In any case, actors have to deal with it, prepared or not. In recent years, hype has developed around drone technologies. The global drone market is estimated to grow from $2 billion in 2016 to nearly $127 billion in 2020 (Moskwa, 2016). The emerging drone technology promises to foster innovations 0007-6813/$ — see front matter # 2017 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.08.001 876 F. Giones, A. Brem that will disrupt existing industries. It is expected that drones will be part of our everyday life, just as smartphones are today; not a day goes by without a new product announcement introducing new ways drones can be used in different contexts. We view drone technology as an example of an emergent technology that has had a long evolutionary path. Advances in artificial intelligence, image processing, and robotics have equipped drones with autonomous functions and have stepped up their transformative potential. Our analysis of drone startups provides the insight to illustrate the co-evolution between entrepreneurial activity and technological developments in the drone industry. We explore the intertwined relationship between technological components evolution and the emergence of new meanings and applications (Norman & Verganti, 2014). We summarize our research findings in a model visualizing industry and technological emergence. The model describes the drivers for innovation and entrepreneurial activity in the initial moments of a new technological wave and, moreover, presents the indirect effects of entrepreneurial activity in a given emerging technology. We describe for innovation managers and entrepreneurs what events trigger the emergence of a technology and attract the needed actors to unleash its transformative potential. The article is organized as follows. First, we give a brief overview of the development in the drone industries in recent years. Then, we describe the technological and entrepreneurial co-evolution in this sector, based on industry reports, news, and market studies as well as interviews with four actors in the drone industry. This finally leads to a discussion of entrepreneurial opportunities and an outlook on the coherence of industrial and technological evolutions. Figure 1. 2. Roots of the hype: The emergence of the drone industry Drones have made headlines quite often in recent years. In late 2016, Amazon’s first drone delivery was highlighted to mark “a milestone in the race to use unmanned vehicles to transform how customers buy and receive goods” (Levin & Soper, 2016). But, in some cases, drones have made negative headlines (Forrest, 2015), either because they crashed in a notorious place (like the White House or a hot spring in Yellowstone National Park) or because they have been used in restricted spaces like airports or sports stadiums. Although the actual notoriety is linked to the popularization of consumer drones, the technology behind this type of drone is an outcome of a complex evolutionary process. First, a clarifying note: the use of the term drone is to describe an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) with a certain degree of autonomy (Hazel & Aoude, 2015). As the term has been popularized, it is often assigned to almost any type of UAV, even those that require constant attention by the remote pilot, like radio-controlled planes; this is an important difference in the military context (Villasenor, 2012) and also when it comes to identifying existing regulations that have an impact on the drone industry. Drones were first mentioned in the early 1900s when they were introduced as targets for military practice, mostly in the U.S. At that time, they had a rather limited autonomy, different from modern target drones. Using unmanned vehicles provided several advantages for military operations. They could be used to gather information on reconnaissance missions or other activities that involved a high risk. From that moment onward, the number of military uses has grown (see Figure 1). The introduction of new technologies has provided Timeline of the military and civilian uses of drones Source: Bumiller & Shanker (2011); Holland Michel & Gettinger (2016); Villasenor (2012) From toys to tools Figure 2. 877 Key dimensions and related technologies in a drone new capacities and functionalities to drones, dramatically increasing their importance in armed conflicts and military operations overall. The introduction and adoption of drones for civilian use has happened in a much shorter time frame than for military use. The miniaturization of electronic components, lighter advanced materials, and the increasing computing power of processing units, among other advancements, make smaller drones more affordable in the market. When looking at the technological components that build a typical civilian-use drone (see Figure 2), it is clear that most of the components have benefited from the last decade’s technological progress, including the miniaturization of high-performing video cameras that have become a usual complement to the quadcopter drones. In the military context, we have observed that technological progress and uses have worked in parallel as a response to a demand pull for drones with enhanced capabilities. In the civilian context, we see an ongoing search for application for the existing drone technology, describing a situation of technology-push. In the civilian context we observe the phenomenon described as the ‘rise of the drones’ (Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, 2016); in only a few years, the number of applications and the industry market size have exploded. Although there has been entrepreneurial activity in the military use of drones, it is in the civilian space that current and future growth is expected (Moskwa, 2016). Meanwhile, the military drone industry is dominated by players that already have strong positions in the industry: Boeing, General Atomics, Lockheed Martin, or Northrop Grumman (Harress, 2014), with the exception of AeroVironment (Fisher, 2013). The civilian drone industry is where we have seen new entrants taking a major position. The cases of the French company Parrot and the Chinese company DJI are clear examples of new and very successful players in this emerging industry. These two companies saw the opportunity to design, manufacture, and commercialize consumer drones; their business model is very similar to a product-based technology company. In fact, Parrot just added drones to its diverse technological products portfolio. For DJI, the exclusive focus on drones paid off as it quickly upgraded and innovated its products to become a market leader. Compared to the providers of military drones, civilian drone makers focus on generating as many product sales as possible and consumerizing the technology, even if this has meant that they could not explore additional revenues such as training, software services, or maintenance as their counterparts did with the military drones. In the next sections, we aim to decipher the interaction between technology evolution and entrepreneurial activity to explain the emergence of the civilian drone industry. To do so, we have reviewed selected literature on industry emergence and entrepreneurial activity; collected industry reports, news, and market analysis; and conducted interviews with representative profiles of the different actors involved in the entrepreneurial activity in the drone industry. 3. Industry emergence: Technological and entrepreneurial co-evolution The emergence of a new industry often goes unnoticed to academic researchers until it has fully emerged and its actors become fully visible (Woolley, 2014). If they miss the formation process, 878 researchers are not able to extract insights on the evolution of the technology and how it relates to the early economic activity of new entrants (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). We first review prior academic literature on the emergence of new industries and then describe the ongoing dynamics in the drone industry. The activation of a new industry requires shared agreement across multiple actors concerning the opportunity to exploit a new technological development. The opportunity recognition activation needs to be combined with a shared perception that there is potential demand and low entry barriers in the new nascent economic activity area. This goes beyond the product itself, connecting market pull and technology push activities (Brem & Voigt, 2009). Prior research studying the early movements in a new industry suggests that two factors characterize the motivations of new entrants: knowledge proximity and complementary assets (Woolley, 2010). Knowledge proximity refers to the access that the actor–—an individual or an organization–—has of the core components of the new technology and its knowledge base. Similar to the idea about the influence of knowledge spillovers (Agarwal, Audretsch, & Sarkar, 2007), new entrants activate knowledge investments prepared by existing firms that would otherwise have stayed unused. The ownership or access to complementary assets determines the entrant’s strategy and pace. In contexts wherein distribution and commercialization are not required for specialized or hard-toacquire assets, more activity is expected than with manufacturing or distributing assets that are difficult to replicate or not available in the market. Similarly, if the key assets to enter the industry are restricted–—for example, via patents–—the expected entrepreneurial activity is much lower than if they are available as a technological standard (Brem, Nylund, & Schuster, 2016). The resulting new entrants can be identified as entrepreneurial startups or as diversifying firms that enter from other industries. These classifications are used by researchers to explain the emerging dynamics of a new industry (Agarwal & Moeen, 2015). When the dominant profile consists of startup firms, the industry and the underlying technology face additional legitimacy challenges; the first movers’ achievements establish a strong precedent (positive or negative) for future entrants (Fisher, Kotha, & Lahiri, 2016). The situation is different when established firms are also present in an emerging industry. On the one hand, these firms can benefit from their existing reputation and complementary assets to compete in the emerging industry; on the other hand, they contribute to the F. Giones, A. Brem overall industry rising its overall credibility and attract additional actors (e.g., investors). As a result, the emergence of a new industry based on a novel technology is surrounded by an uncertainty trifecta (Woolley, 2014): (1) new entrepreneurial firms with limited legitimacy, (2) technology under development, and (3) an undefined market infrastructure. Given this complexity, how does entrepreneurial activity and technology development co-evolve to contribute to the emergence of a new industry? We explore this question in the context of the emergence of the drone industry in the following. 4. Market transformation: From a toy to a professional tool Our analysis of industry news and reports, as well as our interviews with four different actors, suggest that the emergence of the civilian drone industry was not only driven by technology evolution, but also by significant changes to how the technology was perceived by the market. Using Norman and Verganti’s (2014) conceptual framework, we identified that the incremental shifts in technology (i.e., incremental improvements as well as new possibilities) were coupled with changes to the meaning of the technology by, for instance, adding cameras to drones to take scenic pictures or using camera drones as part of the filming tools in a Hollywood movie production. Norman and Verganti (2014) suggested that beside technology-push and demand-pull innovations, there are meaningdriven innovations that benefit from a design that reinterprets an existing technology. The changes in technology meaning give opportunities for new entrants with complementary business models. The popularization of civilian drones created an opportunity for action camera makers to extend their market and for software application developers to start introducing services that were not offered by the original drone manufacturer. We argue that the emergence of the drone industry has gone through several technologymeaning shifts, and that these shifts contributed to opening options for alternative business models that have resulted in the emergence of the industry. As presented in Figure 3, the emergence is observed in three different stages: (1) concept validation, (2) product growth, and (3) market growth. The change from one stage to the other is a result of new entrants’ contributions in either one or many of the developments made to technological components, or in the identification of an application that gave a new meaning to the drone From toys to tools Figure 3. 879 Industry emergence, technology evolution, and technology meaning change technology. In Figure 3, we illustrate the technology components’ evolution with representative examples and highlight the two dominant meanings in the civilian context of drones: as toys used for individual entertainment purposes or as tools used to perform a task or function. In the concept validation stage (first level in Figure 3) we observe startup entrants activating knowledge spillovers (Agarwal et al., 2007) from other industries, in particular from advanced large drones used in a military context. An example of these new entrants is 3D Robotics, founded in 2009 by Chris Anderson, an ex-editor at Wired. The company targeted hobbyists by offering small drones for recreational purposes (Stuart & Anderson, 2015). It quickly became a promising startup and captured the attention of other entrepreneurs. In this stage, the contribution of entrepreneurial activity is to validate the concept that supports the technology-meaning transformation. Another example of an entrepreneurial startup in this stage was Parrot. The French company had already started a few years before, offering Bluetooth headsets, but its announcement in 2010 of the Parrot AR Drone is considered by experts as the event that triggered the concept validation for the consumer drone industry. As argued by Fisher et al. (2016), the early success of these new entrants contributed to the legitimacy of the overall industry. The product growth stage (second level in Figure 3) describes the emergence of the product category. In this stage, even if there are not yet any clear applications for the technology, the new entrants’ pace accelerates as the nascent industry becomes visible to multiple stakeholders. In the drone industry, this stage is characterized by the rapid development of new drones for consumer use and for the introduction of key complementary technologies that generate a technology-meaning shift. While producers like 3D Robotics and Parrot experienced a steady growth in sales for their new drones, it was DJI, a Chinese drone producer based in Shenzhen, that experienced the fastest growth and became the category leader. DJI’s drone incorporated GPS and a video camera in its Phantom product line (see Figure 4). These new features facilitated a technology-meaning change as users started to explore potential applications for drones. In product growth stage, we also see established firms as new entrants. In this instance, firms aimed to diversify their business by entering into the promising drone industry. Examples of such moves are the action camera maker GoPro, which saw how the increasing availability of drones opened new uses and possibilities for its video cameras. As the 880 Figure 4. camera F. Giones, A. Brem DJI Phantom 2 drone equipped with a video product found new meaning, there were also unintended new entrants, as the sales manager of Phase One Camera Systems (world leader in high-end digital photography equipment from Denmark) explained to us: “We realized that more and more we had customers purchasing our professional photography cameras to attach them to drones.” Thus, Phase One started allocating more development resources to address the customer needs for this unexpected use of its products. The market growth stage (third level in Figure 3) describes the moment when the infrastructure of the industry is defined, market segments appear, and there are differentiated product categories for each market segment. In terms of technological development, this could be linked to having a dominant design for the industry set (Brem et al., 2016). It is important to highlight that the transition from product growth to market growth requires a highly active participation of startup entrants that push for technology meaning change applications. An example is DroneThunder, a startup in Spain that offers intrusion detection systems to industrial clients using drones. The company found that its clients could buy and even learn to use drones, but they were not able to analyze and store the video feed captured by the drone. It worked to develop a video analytics platform and experimented with custom-made drones to fit the specific needs of its clients. DroneThunder’s business model is completely different from DJI or other drone makers: It generates revenue through an integrated solution of software and hardware, often using the drones that the clients already have. In a similar situation, Aerialtronics, based in the Netherlands, offers inspection services to identify maintenance issues in wind farms or in difficult-to-reach telecommunication antennas. In 2014, it started to develop customized drones with more accurate video data, flight reliability, and tolerance for a variety of weather conditions; standard commercial solutions would just fail in these tasks. Once the industry reaches this third stage, it is the moment when the awareness of the industry reaches even nondirectly linked stakeholders. In the last years we have seen how both general consulting and insurance firms have increased their attention toward the emergent industry (see Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty, 2016; Marsh, 2015a; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016). This is also the moment when large actors step in as entrants; drone-specific features in the new processors offered by Qualcomm (Vincent, 2015) are significantly extending the possible uses of drones. It is also in this stage when applications become industry segments and differentiate among them. This process of market structuring also opens opportunities to entrepreneurs as new entrants, like RobSense Technology, a new startup that is creating the nextgeneration flight controllers for industrial-use drones. Based in Hanghzhou, China, but with R&D partnerships in Denmark and the U.S., this startup addresses the needs of companies that require tailored drones for professional use in contexts where safety and reliability are a priority (e.g., companies like Aerialtronics1). The flight controller equipment can be customized so that industrial clients can then offer new drone-based services. There is also a dark side to the process of industry emergence. The risks taken by the new entrants do not always pay off. Sometimes, it is because their targeted area of application does not respond as expected and, other times, because the competition of new entrants becomes too aggressive and does not allow for mistakes. The above-mentioned example of 3D Robotics, pioneers in the civilian drone industry in the U.S., is also an example of the struggle to stay competitive in an emerging industry. The company had problems with a new drone product launch; since then it has been severely downsized, not being able to keep up with the market development pace (Mac, 2016). Much of the same happened to GoPro as it aimed to revive its revenues by offering a bundled drone and camera solution; the product launch, already delayed, was swiftly followed by a product recall. Design flaws and/or the malfunction of technical components were behind the error that now jeopardizes the future of the whole company (Popper, 2016). Hence, any process of industry emergence is always 1 To see Aerialtronics’ adaptable drone solution for inspection and photography services, visit https://www.aerialtronics.com/ wp-content/uploads/2015/04/aerialtronics-altura-zenithfront.jpg From toys to tools linked with a timing risk, which is only manageable to a certain extent. There are many examples to underline that even big and experienced companies like Nestlé have challenges (e.g., in the case with Nespresso) (Brem, Maier, & Wimschneider, 2016). 5. Room for growth: Entrepreneurial opportunities in the drone industry The drone industry provides a unique understanding of the different roles that new entrants have in developing the technology and its meaning. New entrepreneurial startups contribute to the creation of the new industry, but so do the diversifying firms that decide to invest in the nascent industry solutions. Furthermore, based on the drone industry case, the participation of entrepreneurial activity is not only essential to advance in the first stage of concept validation, but also to move the industry through the following emergence stages. Such findings evidence the fragile equilibrium that emerging industry leaders need to find between keeping low entry barriers that encourage complementary offerings and protecting their market position against direct competitors. Lessons from new entrants in Figure 5. 881 platform-based markets should be applicable to this context (see Zhu & Iansiti, 2012). Nevertheless, the drone industry provides evidence that unless the technology and market structure are mature, there is still room for unexpected challenges as the aforementioned attempt by GoPro exemplifies. A more detailed review of the findings from the drone industry emergence suggests a plausible reason as to why it does not behave as a platform model. The cycle of emergence does not stop unless there are no further potential applications (opportunities) to explore (Woolley, 2010). As we position the current applications based on their current stage (see Figure 5), we observe that the recreational use, photography, and media applications that now generate most of the revenue in the drone industry–—60—70% of the $2 billion of the actual commercial-use market (Moskwa, 2016; Thibault & Aoude, 2016)–—will only be a small fraction of what the industry is expected to be in 2025. In an attempt to quantify the future value of drone applications, analysts have suggested that infrastructure inspections, agriculture, transport, and security could account for most of the $127 billion of value annually captured by this industry in the near future (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2016). Existent and new applications in the drone industry Source: Hazel & Aoude (2015); Marsh (2015b); PricewaterhouseCoopers (2016) 882 Despite the potential flaws in such future predictions, it remains relevant that the applications that have brought the drone industry to its current status might not be the ones that define its future. These days, drones are used as toys. They can be purchased at any toy store in different sizes, colors, etc. We can see young kids, parents, and grandparents together in these stores getting excited about the possibilities drones offer. But this does not have much to do with professional applications, which are already in the market, although not in such a big scale like the privately used drones. For instance, maintenance of windmills or power supply lines brings very different requirements to the drones: operation times, quality of images and videos, reliability, etc. Moreover, software is needed to analyze the material professionally, staff training is needed to educate people to operate it, as well as maintenance contracts and consulting services. An example of a startup that exploited this opportunity is Hemav. The company completed its inspection and mapping services in Spain with training courses to fly drones for customers’ staff members. This offers the chance for entrepreneurs to develop their own niche as a solution provider rather than as a seller of standard drones–—in the best case with the implementation of an industry standard. The result is the introduction of a servicebased business model that has helped the company not only get revenue by offering industrial services with drones, but also get additional revenue through training programs. Thus, there are also opportunities for existent firms interested in entering the drone industry. The development of these applications is, in some cases, dependent on new technological developments and, in others, on changes to existent regulations. While technological developments mostly benefit from the development of new applications and uses, the effects of regulation in an industry emergence are more easily described using Bernoulli’s principle: If a potential application is constrained by regulation, it does not expand and entrepreneurial activity flows into other more receptive industries or geographical contexts. The evolution of promising areas of application in the drone industry, such as inspection services for agriculture and farming, have begun to be explored by companies like Wingtra or Botlink that have developed their own drones and cloud-based software solutions for this market.2 But their software 2 To see the WingtraOne drone for precision agriculture and learn about its specifications, visit https://wingtra.com/ product/ F. Giones, A. Brem and hardware solutions are dependent on both advances in the technology behind the cameras, sensors, and processors, and on new entrepreneurs attracted by the idea of offering services using their products to end customers (see Figure 5). These are interesting examples of alternative startup business models: While Wingtra offers its own enhanced drones, tailored to the specific needs of a customer segment (agriculture), Botlink follows a service subscription business model approach (Trimi & Berbegal-Mirabent, 2012). Botlink does not sell its own drones, but subscriptions to an app that helps industrial clients to capture, store, and analyze mapping data. Looking into the future, logistics companies have been considering the drone industry with a combination of interest and fear. As an expert in the recently created Platform for Unmanned Cargo Aircraft (PlatformUCA) described, there is a clear opportunity for using drones for large cargo logistics. It could create a new market for direct cargo deliveries to locations with difficult access or where an urgent response is needed. Nevertheless, these drone applications will trigger the entry of new firms that help to push the batteries and engines currently used into a new dimension. But considering the fast-paced technological development in other areas, as in the evolution from the mobile phone to the smartphone, such technologies might have the potential in the future to enable such cargo deliveries even though we might currently think of this option as an unfeasible and futuristic idea. The further development of the drone industry highly depends on the increased capacity and reliability of its technical components, but the survival of the new entrants will also depend on their ability to identify and defend solid business models. The fast evolution of the drone industry has already shown the challenges for firms that rely only on offering drone hardware solutions for their revenue; even the current market leader, DJI, is starting to shift its business model to accelerate the creation of third-party apps in its platform. The co-existence of a diversity of business models is a common phenomenon in emerging industries (e.g., the cases of the different startups in the sharing economy: Cohen & Kietzmann, 2014; Muñoz & Cohen, in press), in which new entrants need to strike the right balance between customer value creation, financial sustainability, and their growth ambitions. This can be a long process; for instance in the case of social media companies like Twitter, the success in terms of engagement or number of users has not automatically translated into a long-term solid growth and business model (Ingram, 2015). From toys to tools As long as there is room for new entrepreneurs to enter and experiment with the technology and business models, the drone industry will stay engaged in emergence cycles and offer plenty of opportunities for new and existent firms. 6. Final thoughts Based on military use in the 1900s and civil use from the 2000s, hype around drones and their applications has rapidly evolved in the last decade. The rapid development of key technologies in the fields of aerial capacity, flight control, position control as well as communication led to a complex and specific field for UAS. This industry emerged because of technological evolution, but also because of technological meaning change, from concept validation with basic functionalities to product and market growth with new sensor and control technologies. With this conceptualization, we explained the evolution of drones from a toy to a professional tool and we extracted insights on how technology and new entrants’ business models matter in the emergence of new technology-driven industries. With this article, we hope to clarify how the drone industry has evolved and how it may evolve in the future. Once startups and established firms put their competencies together, professional (tool) and consumer (toy) applications will lead to a growing industrial field. This development will be as revolutionary as mobile phones, smartphones, or the internet, opening opportunities to both entrepreneurs and established companies to participate in defining the future. References Agarwal, R., Audretsch, D., & Sarkar, M. B. (2007). The process of creative construction: Knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurship, and economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(3/4), 263—286. Agarwal, R., & Moeen, M. (2015). Entrepreneurial startups (de novo), diversifying entrants (de alio), and incumbent firms. In M. Augier & D. Teece (Eds.), The Palgrave encyclopedia of strategic management. Available at https://link.springer. com/referencework/10.1057%2F978-1-349-94848-2 Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in: The institutional context of creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645—670. Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty. (2016). Rise of the drones: Managing the unique risks associated with unmanned aircraft systems UAS [White paper]. Available at https://www.agcs. allianz.com/assets/PDFs/Reports/AGCS_Rise_of_the_ drones_report.pdf Argyres, N., Bigelow, L., & Nickerson, J. A. (2015). Dominant designs, innovation shocks, and the follower’s dilemma. Strategic Management Journal, 36(2), 216—234. 883 Brem, A., Maier, M., & Wimschneider, C. (2016). Competitive advantage through innovation: The case of Nespresso. European Journal of Innovation Management, 19(1), 133—148. Brem, A., Nylund, P. A., & Schuster, G. (2016). Innovation and de facto standardization: The influence of dominant design on innovative performance, radical innovation, and process innovation. Technovation, 50/51(April/May), 79—88. Brem, A., & Voigt, K.-I. (2009). Integration of market pull and technology push in the corporate front end and innovation management–—Insights from the German software industry. Technovation, 29(5), 351—367. Bumiller, E., & Shanker, T. (2011, June 19). War evolves with drones, some tiny as bugs. The New York Times. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/20/world/20drones. html Cohen, B., & Kietzmann, J. (2014). Ride on! Mobility business models for the sharing economy. Organization and Environment, 27(3), 279—296. Dedehayir, O., & Steinert, M. (2016). The hype cycle model: A review and future directions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 108, 28—41. Fisher, G., Kotha, S., & Lahiri, A. (2016). Changing with the times: An integrated view of identity, legitimacy, and new venture life cycles. Academy of Management Review, 41(3), 383—409. Fisher, L. M. (2013, May 28). Flight of the drone maker. Strategy +Business. Available at https://www.strategy-business.com/ feature/00187?gko=ac04a Forrest, C. (2015, March 20). 12 drone disasters that show why the FAA hates drones. TechRepublic. Available at http:// www.techrepublic.com/article/12-drone-disasters-thatshow-why-the-faa-hates-drones/ Harress, C. (2014, January 10). 12 companies that will conquer the drone market in 2014 and 2015. International Business Times. Available at http://www.ibtimes.com/12-companieswill-conquer-drone-market-2014-2015-1534360 Hazel, B., & Aoude, G. (2015). In commercial drones, the race is on [White paper]. Oliver Wyman. Available at http://www. oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/global/en/ 2015/apr/Commercial_Drones.pdf Holland Michel, A., & Gettinger, D. (2016, September). The drone revolution revisited: An assessment of military unmanned systems in 2016. Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College. Available at http://dronecenter.bard.edu/ publications/drone-revolution-revisited/ Ingram, M. (2015, October 29). What if the Twitter growth everyone is hoping for never comes? Fortune. Available at http://fortune.com/2015/10/29/twitter-growth/ Levin, A., & Soper, S. (2016, December 14). An airdrop of popcorn makes Amazon drone delivery history. Bloomberg Technology. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/ 2016-12-14/with-an-airdrop-of-popcorn-amazon-makesdrone-delivery-history Mac, R. (2016, October 5). Behind the crash of 3D Robotics, North America’s most promising drone company. Forbes. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryanmac/2016/10/05/ 3d-robotics-solo-crash-chris-anderson/#38bcf2613ff5 Marsh. (2015a). Dawning of the drones: The evolving risk of unmanned aerial systems [White paper]. Available at https://www.marsh.com/us/insights/research/dawningof-the-drones.html Marsh. (2015b). Drones–—A view into the future for the logistics sector? [White paper]. Available at https://www.marsh. com/uk/insights/research/drones-view-into-the-future-forthe-logistics-sector.html 884 Moskwa, W. (2016, May 9). World drone market seen nearing $127 billion in 2020, PwC says. Available at https://www. moneyweb.co.za/news/tech/world-drone-market-seennearing-127bn-2020-pwc-says/ Muñoz, P., & Cohen, B. (in press). Mapping out the sharing economy: A configurational approach to sharing business modeling. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. Norman, D. A., & Verganti, R. (2014). Incremental and radical innovation: Design research vs. technology and meaning change. Design Issues, 30(1), 78—96. Popper, B. (2016, November 11). Why GoPro’s Karma drone came crashing down. The Verge. Available at http://www. theverge.com/2016/11/11/13597902/gopro-karma-dronerecall-crash-battery-fail PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2016, May 9). Global market for commercial applications of drone technology valued at over $127 bn. Available at http://press.pwc.com/News-releases/ global-market-for-commercial-applications-of-dronetechnology-valued-at-over-127-bn/s/ac04349e-c40d-47679f92-a4d219860cd2 Stuart, T., & Anderson, C. (2015). 3D Robotics: Disrupting the drone market. California Management Review, 57(2), 91—112. F. Giones, A. Brem Thibault, G., & Aoude, G. (2016, June 29). Companies are turning drones into a competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review. Available at https://hbr.org/2016/06/companiesare-turning-drones-into-a-competitive-advantage Trimi, S., & Berbegal-Mirabent, J. (2012). Business model innovation in entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(4), 449—465. Villasenor, J. (2012, April 12). What is a drone, anyway? Scientific American. Available at https://blogs.scientificamerican. com/guest-blog/what-is-a-drone-anyway/ Vincent, J. (2015, December 31). Qualcomm video shows how much smarter drones will get in 2016. The Verge. Available at http://www.theverge.com/2015/12/31/10693066/ qualcomm-snapdragon-flight-preview Woolley, J. L. (2010). Technology emergence through entrepreneurship across multiple industries. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(1), 1—21. Woolley, J. L. (2014). The creation and configuration of infrastructure for entrepreneurship in emerging domains of activity. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 38(4), 721—747. Zhu, F., & Iansiti, M. (2012). Entry into platform-based markets. Strategic Management Journal, 33(1), 88—106.