Merenstein & Gardner's Handbook of Neonatal Intensive Care, 9e By Sandra Gardner, Brian Carter, Mary Enzman-Hines, Susan Niermeyer

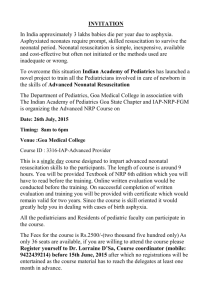

advertisement