Jacob Zuma: Martyr or Delinquent? Analysis of Political Situation

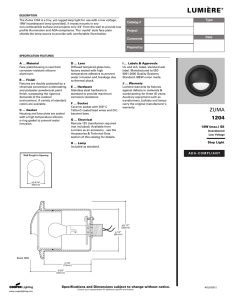

advertisement

#JacobZuma A debate on whether former president Jacob Zuma a martyr or constitutional delinquent Jacob Zuma: A politician with an overactive martyr complex Most people know Zuma is simply evading accountability for facilitating siphoning out of the public purse, writes UJ associate professor Mcebisi Ndletyana. South Africa’s Constitutional Court ruling to imprison the country’s former president, Jacob Zuma, was unprecedented. But it wasn’t unexpected. The author of the majority judgment, Justice Sisi Khampepe, captured the inevitability of the outcome somewhere in the middle the ruling, when she noted: “For I am not in the habit of playing my cards close to my chest, let me, at this earliest opportunity, state that Mr Zuma has earned himself a punitive sanction of direct and unsuspended sentence.” Nor was Zuma’s wrongful behaviour guided by any thought-out, long term strategy. It began as an instinctive reaction to evade accountability, but quickly hardened into a mode of behaviour as Zuma failed to come up with a reasonable defence. Let’s start with the inevitability of the custodial sentence of 15 months. The Constitutional Court correctly understands its role in a much broader sense than simply deciding the constitutionality of matters before it. Situated at the helm of South Africa’s judiciary, it is the leader of the three constituent elements of our democracy. No ordinary act of defiance The Constitutional Court settles disputes between contending parties based on the commonly agreed set of basic rules, also known as the social contract, adopted at the inception of South Africa’s democratic order. The fact of citizenship binds South Africans to abide by these basic rules in order to assure their collective well-being. A threat to that collective well-being arises when the ability of the Constitutional Court to enforce collective agreements is challenged. Zuma’s conduct challenged the country’s normative foundation. He didn’t just refuse to appear before the Zondo Commission of inquiry into state capture and corruption, but disobeyed an order of the Constitutional Court. Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo, chair of the commission, had successfully convinced the Constitutional Court to order Zuma to appear before the commission, following repeated refusals. This meant that, unlike everybody else, Zuma was exempting himself from the law that ought to apply equally to everybody. Because he is a former president, Zuma’s refusal was no ordinary act of defiance. According to Justice Khampepe, he enjoys a “unique and special political position”, which imbues him with “a great deal of power to incite others to similarly defy court orders because his actions and any consequences, or lack thereof, are being closely observed by the public. “If his conduct is met with impunity, he will do significant damage to the rule of law.” Even more worrisome to the Constitutional Court was that Zuma was not just a no-show in court, or at the commission. He made statements that were inflammatory and offensive towards judges, denouncing them as part of a political conspiracy to jail him. Zuma was effectively inciting the public against the courts. He had positioned himself as a nemesis of the judiciary, which is a critical custodian of our democratic order. Ultimately, the Constitutional Court was forced to choose between two courses: capitulate to Zuma’s megalomania, or uphold the rule of law. Capitulation was never an option, as Justice Khampepe recalled Nelson Mandela’s counsel at the inauguration of the Constitutional Court back in 1995: “We expect you to stand on guard not only against direct assault on the principles of the constitution, but against insidious corrosion.” Now that Zuma faces prison some appear bewildered about the intention of his actions. Motives Why did he defy the law so brazenly in the face of possible imprisonment? Is this part of some hidden strategy we don’t know about? No – there’s no hidden strategy here. Zuma simply had no legal defence. That showed at his initial appearance at the commission. He told a long tale, trying to stitch together unrelated incidents in an attempt to paint himself as a victim of an international conspiracy. One of such incidents “to deal” with him, Zuma mentioned, was his removal as chief of counter-intelligence. What he conveniently left out of his testimony that day was that former president Thabo Mbeki, who was then his closest ally from back in the late 1970s, had also been removed as the ANC’s leading negotiator – a position he had assumed from the mid-1980s. And the instigators of this change of guard were no international conspirators, but his own leftist comrades in the African National Congress, Joe Slovo and Mac Maharaj, with the newly elected secretary-general, Cyril Ramaphosa, in the forefront. The old leftists just wanted to be in control of negotiations, and resented that they had no influence over Mbeki and Zuma. For Ramaphosa it was an opportunity to make history. Zuma’s tale at the commission was fine as long as he was the one telling it, without anyone questioning him. The problem came when he had to be questioned. And the questions were not only going to expose the falsity of his tale, but also his complicity in many other instances of impropriety that had been presented to the commission. He tried discrediting witnesses with accusations of being spies. That trick did not work. The commission still insisted on his appearance, but Zuma knew doing so would be his undoing. To avoid exposure, a no-show at the commission became a plausible escape. Because people were likely to ask why he wasn’t going to the commission when everybody else did, Zuma couldn’t say no, angizi (I am not coming)! He had to come up with an elaborate explanation, and so he went back to his old conspiracy theory. This time around Zuma threw in Zondo and his colleagues on the bench. He has labelled them agents in the hands of his enemies. This was just a cooked-up story to ward off questions about non-appearance at the commission. What then appears as an attempt at martyrdom – imprisonment over deference to courts – is really the result of Zuma having run out of ideas to defend himself at the commission. Martyrdom is almost impossible without a cause, and Zuma has none. Most people know that he’s simply evading accountability for facilitating siphoning out of the public purse. There may be protests here and there, by his militia force trying to hustle a living, but there won’t be any significant backlash.That is because Zuma simply has no cause. What’s there to die for? The man is simply a wily politician trying to evade the law. Mcebisi Ndletyana is the author of Anatomy of the ANC in Power: Insights from Port Elizabeth, 1990 to 2019 (HSRC Press, 2020). Mcebisi Ndletyana, Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Johannesburg. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Victim or Martyr: The Spectacular Rise and Fall Of Jacob Zuma By Inside_Politics, June 30, 2021 https://insidepolitic.co.za/victim-or-martyr-the-spectacular-rise-and-fall-of-jacob-zuma/ CHARLES MOLELE| JACOB Zuma, former president of the African National Congress (ANC), must turn himself in to the nearest police station within the next five days – either at Nkandla, or the Johannesburg Central prison, once a notorious site of interrogation, torture and abuse by the South African Security Police (SAPS) during the apartheid era. If he fails to do so, the police must take all steps necessary to ensure that he is arrested and immediately serves his prison sentence, the Constitutional Court said on Tuesday in a landmark case. This is the first time in the South African history that a former president has been sentenced to prison. The much-anticipated incarceration of Zuma, a master of dark arts politics, has deepened political divisions within the ANC and divided public opinion in South Africa, with pro-Zuma supporters saying they are prepared to lay down their lives for him. A veteran of the antiapartheid struggle, Zuma committed a cardinal mistake by refusing to appear before the State Capture Inquiry and its chairperson deputy chief justice Raymond Zondo. Even after he was persuaded by the ANC’s top leadership to appear before the Zondo Commission, he dug in his heels. This was odd because when he took office, Zuma swore before Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng and South Africans that he will be ‘faithful to the Republic of SA and will obey, observe, uphold, and maintain the Constitution and all other law[s] of the republic.’ “I solemnly and sincerely promise that I will always promote all that will advance the Republic and oppose all that may harm it,” he said then. In a scathing judgment, acting deputy chief justice Sisi Khampepe said no one is above the law, and Zuma’s attempts ‘to evoke public sympathy through unfounded allegations fly in the face of reason and are an insult to the constitutional dispensation for which many women and men fought and lost their live.’ “Never before has the judicial process been so threatened,” Khampepe said. “If with impunity litigants are allowed to decide which orders they may wish to obey and which they wish to ignore, then our constitution is not worth the paper on which it is written.” Khampepe said these statements were unfounded, and went beyond what could constitute legitimate criticism of the judiciary. Reacting to her judgment, Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans Association (MKMVA) spokesperson Carl Niehaus said the Constitutional Court’s decision to sentence Zuma to 15 months imprisonment was a ‘fundamental, absolute outrage’. “The imprisonment of President Jacob Zuma is totally unacceptable. In fact it is an utter outrage. Now it is our revolutionary democratic right and duty to register our outrage, and resistance to this, in no uncertain terms, and we will,” Niehaus said. “We fully concur with President Zuma that he is unjustly being targeted, and that the law is being abused for factional political reasons. As President Zuma has stated he was one of the most prominent liberation fighters, and ANC political leaders, who gave his all for our current National Constitution to be adopted, and he cannot allow now that the very same Constitution is being abused. For the Constitutional Court to be part of such a disgraceful situation is an utter shame.” Mzwanele Manyi, spokesperson for the Jacob Zuma Foundation, said the court’s judgment was unconstitutional and should be challenged because it was not even unanimous, citing points raised by the minority judgment.“The unconstitutionality of this judgment should be challenged. It is an infringement of President Jacob Zuma’s rights,” said Manyi. Manyi declined to comment further, saying in a tweet that Zuma’s legal team was currently studying the judgment. “Once President Zuma has received legal advice, a full statement will be issued. It cannot be ruled out that President Zuma may soon address the nation,” said Manyi. ANC spokesperson Pule Mabe said the party has noted the judgment of the Constitutional Court against Zuma. The ANC was currently studying the judgment, he said. “Without doubt this is a difficult period in the movement and we call upon our members to remain calm. The meeting of the National Executive Committee (NEC) scheduled to take place this weekend, will reflect on implications and consequences of the judgement,” said Mabe. Zuma, 79, is currently based at his homestead in Nkandla, in deep rural KwaZulu-Natal, following his ousting by the ANC’s national executive committee in 2018. By common consent, Zuma was the consummate politician. Growing up as a poor teenage herd-boy in Nkandla, Zuma decided early on to dedicate his life to the anti-apartheid struggle, spending years in exile and jail before rising to the country’s top job. Struggling from the bottom, Zuma worked his way through underground politics as the intelligence chief of the ANC. He embodied the true liberator. Illiterate and with no formal education to speak of, Zuma made it to the pinnacle of political power in South Africa through effort and sheer determination.His story, far from being one of triumph, is also a story of great Shakespearean tragedy – of one bad decision after another, including an alleged rape of a struggle stalwart’s daughter, his relationship with convicted fraudster Schabir Shaik, and the controversial Gupta family. Former national director of public prosecutions, Vusi Pikoli, said in his book that with the benefit of hindsight, he would have charged Zuma along with Shaik, adding that they were inextricably linked to the allegations and the flow of money showed this close proximity. “Shaik was sustaining Zuma, peddling his name and using his influence as a public official, and it was proven that money was paid,” said Pikoli. Riding high on the crest of his fame and charisma, Zuma ascended to power in 2007 at the historic Polokwane elective conference.During his nine years in office, he took a more active role in the government than his aloof predecessor Thabo Mbeki, introducing several policy changes and offering all HIV-positive babies under the age of one with anti-retroviral drugs. The act marked a final break with the stance of Mbeki, whose unwillingness to implement HIV policies and offer drugs led to the premature deaths of more than 300 000 people. Zuma campaigned in the party’s activities and elections in a more charismatic than ever before.His posters used colourful slogans to ramp up the ‘radical economic transformation’ agenda of the left. To quote political analyst and academic, Mervyn Gumede, Zuma energised resistance — ‘even as he destroyed the moral leadership of the ANC, which will take a long time to recover if ever.’ But instead of using his years in office to rebuild the country, fight corruption and transform the economy, he did the opposite; he disbanded the Scorpions, destroyed state institutions, SOEs and surrounded himself with yes-men and sycophants. Even senior leaders of the labour federation Cosatu and the SA Communist Party backed him in a belief he would accelerate measures to reduce white ownership of the economy. The left projected their own ideological fantasies onto Zuma – they saw in him as hope for a “left turn” and a repudiation of the neoliberal economics which they associated with Mbeki. But, in the blink of an eye, he lost everything. Consequently, the SACP and Cosatu have been compelled to recognise that Zuma and his corrupt support networks are indeed a cancer in South African politics, shamelessly enriching themselves in a country still defined by poverty and extreme inequality with unemployment at 27.7% in the first quarter of 2017, and youth unemployment standing at 38% History will surely judge him harshly – particularly his defiance of the Zondo Commission and for making unwarranted attacks on the judiciary. The cost of Zuma’s destruction of state institutions and the erosion of public trust, including his expensive habit of firing Finance Minister, allegedly at the Gupta’s behest, is vast and will make it harder for the South African state to make up for lost time in transforming the South African society for a long time to come. Zuma is expected to address the nation to respond to the news of his prison sentence by the court, the Jacob Zuma Foundation hinted in a tweet on Tuesday shortly after the judgment.