International Accounting, 6e Doupnik, Timothy, Finn Mark, Gotti Giorgio, Perera Hector-2

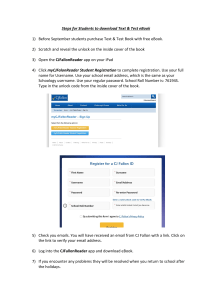

advertisement