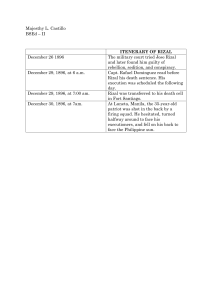

Philippine History: Controversies Spaces for Conflict and Making Sense of the Past: Historical Interpretation History- the study of the past and how it impacts the present through its consequences. Geoffrey Barraclough defines history “the attempt to discover, on the basis of fragmentary evidence, the significant things about the past." He also notes “the history we read, though based on facts, is strictly speaking, not factual at all, but a series of accepted judgments.” Historians- they utilize facts collected from primary sources of history and then draw their own reading so that their intended audience may understand historical events "makes sense of the past." Multiperspectivity- a way of looking at historical events, personalities, developments, cultures, and societies from different perspectives. Historical writing- is biased, partial, and contains preconceptions. - - - - - Historian decides on what sources to use, what interpretation to make more apparent, depending on what his/her end is. Historians may misinterpret evidence, attending to those that suggest that a certain event happened, and then ignore the rest that goes against the evidence. Historians may omit significant facts about their subject, which makes the interpretation unbalanced. Historians may impose a certain ideology to their subject, which may not be appropriate to the period the subject was from. Historians may also provide a single cause for an event without considering other possible causal explanations of said event. Case Study 1: Where Did the First Catholic Mass Take Place in the Philippines? Butuan- has long been believed as the site of the first Mass (over 3 centuries). - culminating in the erection of a monument in 1872 near Agusan River, which commemorates the expedition’s arrival and celebration of Mass on 8 April 1521. 2 primary sources that historians refer to in identifying the site of the first Mass: 1. Francisco Albo’s Log- a pilot of one of Magellan’s ship, Trinidad. Didn’t mention mass, plantation or cross lang in Limasawa He was one of the 18 survivors who returned with Sebastian Elcano on the ship Victoria after they circumnavigated the world. 2. Account by Antonio Pigafetta- Primo viaggio intorno al mondo (First Voyage Around the World). Pigafetta and Albo, was a member of the Magellan expedition and an eyewitness of the events, the first Mass. Albo and Pigafetta’s testimonies coincide and corroborate each other. Pigafetta gave more details on what they did during their weeklong stay at Mazaua. Case Study 2: What Happened in the Cavite Mutiny? 1872- a historic year of 2 events: 1. Cavite Mutiny - a major factor in the awakening of nationalism among the Filipinos of that time. 2. Martyrdom of the three priests: Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, GOMBURZA. These events are very important milestones in Philippine history and have caused ripples throughout time, directly influencing the decisive events of the Philippine Revolution toward the end of the century. Spanish Accounts of the Cavite Mutiny Jose Montero y Vidal (Spanish historian)– his documentation centered on how the event was an attempt in overthrowing the Spanish government in the Philippines. His account of the mutiny was criticized as woefully biased and rabid for a scholar. Governor General Rafael Izquierdo- Another account from the official report implicated the native clergy, who were then, active in the movement toward secularization of parishes. 20 January 1872- district of Sampaloc celebrated feast of the Virgin of Loreto and came with it were some fireworks displays. The Cavitenos allegedly mistook this as the signal to commence with the attack. 17 February 1872, the GOMBURZA were executed to serve as a threat to Filipinos never to attempt to fight the Spaniards again. *These two accounts corroborated each other. Exemption from the Tribute 1. TAXATION Filipinos paid taxes to Spain A. TRIBUTE (TRIBUTO) the Filipinos were compelled to pay tribute called TRIBUTO, to the colonial government. Those who paid tribute were individuals BETWEEN 16 TO 60 Y.O B. CEDULA (Personal Identification Paper) In 1884, Tribute was nullified and replaced by the CEDULA. The cedula was a certificate identifying the taxpayer. It recorded his name, age, birthplace, marital state, occupation, place of residence, nationality and sex. C. DIEZMOS PREDIALES or TITHES The diezmos prediales was a tax consisting of one-tenth (1/10) of the produce of one's land. Polos y Servicios (force labor) All male Filipinos (polistas) from 18 to 60 years of age were required to give their free labor, called polo, to the government. This labor was for 40 days a year, reduced to 15 days in 1884. Differing Accounts of the Events of 1872 Two other primary accounts exist that seem to counter the accounts of Izquierdo and Montero. 1. Dr. Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de Tavera- a Filipino scholar and researcher, who wrote a Filipino version of the bloody incident in Cavite. 2. Edmund Plauchut- A French Writer, complement Tavera account and analyzed the motivations of the 1872 Cavite Mutiny Case Study 3: Did Rizal Retract? Jose Rizal -a hero of the revolution for his writings that center on ending colonialism and liberating Filipino minds to contribute to creating the Filipino nation. La Liga Filipina- org of Rizal Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo- His essays vilify not the Catholic religion, but the friars. “The Retraction”- a document declares Rizal’s belief in the Catholic faith and retracts everything he wrote against the Church. The Balaguer Testimony (Fr. Vicente Balaguer) He said Rizal woke up several times, confessed four times, attended a Mass, received communion, and prayed the rosary, all of which seemed out of character. Testimony of Cuerpo de Vigilancia - No Fr. Balaguer mentioned in the testimony. Case Study 4: Where Did the Cry of Rebellion Happen? Cry of Rebellion- Momentous events swept the Spanish colonies in the late 19th century, including the Philippines. “El Grito de Rebelion” to mark the start of these revolutionary events, identifying the places where it happened. This happened in August 1896, northeast of Manila, where they declared rebellion against the Spanish colonial government. Teodoro Agoncillo- emphasizes the event when Bonifacio tore the cedula or tax receipt before the Katipuneros who also did the same. Some writers identified the first military event with the Spaniards as the moment of the Cry, for which, Emilio Aguinaldo commissioned an “Himno de Balintawak” to inspire the renewed struggle after the Pact of the Biak-na-Bato failed. Cry of Balintawak- celebrated every 26th of August. The site of the monument was chosen for an unknown reason. Different Dates and Places of the Cry Lt. Olegario Diaz- a guardia civil, identified the Cry to have happened in Balintawak on 25 August 1896. Teodoro Kalaw- Filipino historian, marks the place to be in Kangkong, Balintawak, on the last week of August 1896. Santiago Alvarez- a Katipunero and son of Mariano Alvarez, leader of the Magdiwang faction in Cavite, put the Cry in Bahay Toro in Quezon City on 24 August 1896. Pio Valenzuela- known Katipunero and privy to many events concerning the Katipunan stated that the Cry happened in Pugad Lawin on 23 August 1896. Historian Gregorio Zaide- identified the Cry to have happened in Balintawak on 26 August 1896 Teodoro Agoncillo- put it at Pugad Lawin on 23 August 1896, according to statements by Pio Valenzuela. Research by historians Milagros Guerrero, Emmanuel Encarnacion, and Ramon Villegas claimed that the event took place in Tandang Sora’s barn in Gulod, Barangay Banlat, Quezon City, on 24 August 1896. Source: Guillermo Masangkay, “Cry of Balintawak” - On August 26th, a big meeting was held in Balintawak, at the house of Apolonio Samson, then cabeza of that barrio of Caloocan. Pio Valenzuela, “Cry of Pugad Lawin” - Using primary and secondary sources, four places have been identified: Balintawak Kangkong Pugad Lawin Bahay Toro Dates vary: 23, 24, 25, or 26 August 1896. Valenzuela’s account- is red flag kay pa iba-iba. Guerrero, Encarnacion, and Villegas- all these places are in Balintawak, then part of Caloocan, now, in Quezon City. - As for the dates, Bonifacio and his troops may have been moving from one place to another to avoid being located by the Spanish government, which could explain why there are several accounts of the Cry.