James O ’ Driscoll

BRITAIN

FOR LE ARNE RS OF E N G L I S H

James O ’Driscoll

BRITAIN

FOR L E ARNE RS OF E N G L I S H

O X FO R D

OXTORD

U N I V E R S I T Y PR ESS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0 x 2

6dp

Oxford University Press is a d ep artm en t of the University o f Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

A uckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lum pur Madrid M elbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

W ith offices in

A rgentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

G uatem ala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

o x f o r d and o x f o r d E n g l i s h are registered trade m arks o f

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain o th er counfft^S

© Oxford University Press 2009

The m oral rights o f th e a u th o r have been asserted

Database rig h t Oxford University Press (maker)

First published 2009

2013 2012 20 u 2010 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No unauthorized photocopying

All rig hts reserved. No p a rt o f this publication m ay be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system , or transm itted, in any form or by any m eans,

w ithout th e prior perm ission in w ritin g o f Oxford University Press,

or as expressly perm itted by law, or un d er term s agreed w ith the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside th e scope of the above should be sen t to th e ELT Rights D epartm ent,

Oxford University Press, at th e address above

You m ust n ot circulate this book in any o th er binding o r cover

and you m ust im pose this sam e condition o n any acquirer

Any w ebsites referred to in this publication are in th e public dom ain and

th e ir addresses are provided by Oxford University Press for inform ation only.

Oxford University Press disclaims any responsibility for the content

is b n

: 978 0 1 9 4306 44 7

Printed in China

ACKN O W LED GEM EN TS

The authors and publisher are grateful to those who have given permission to reproduce

the following extracts and adaptations o f copyright material: pp31 & 116E xtract

from Notesfrom a Small Island by Bill Bryson published by Black Swan in 1996.

Reproduced by perm ission o f Random House Group Ltd. p44 Extract from

‘Mad about Plaid’ by A. A. Gill, The Sunday Times, 23 January 1994 © Times

Newspapers Ltd 1994. Reproduced by perm ission o f N I Syndication Ltd.

p44 E xtract from ‘W ho gives a C aber Toss’ by Harry Ritchie, The Sunday Times,

23 January 1994 © Times Newspapers Ltd 1994. Reproduced by perm ission

o f NI Syndication Ltd. p55 Extract from ‘Events: Cross-Border w eekend event

2007’ from http://w ww.schoolsacrossborders.org. Schools Across Borders is a

registered charity in Ireland. Reproduced by perm ission, p i 32 E xtract from

A sad lesson' by Paul Sims from The Daily Mail, 26 O ctober 2007 © Daily Mail.

Reproduced by perm ission, p i 91 Extract from ‘A saboteur in the shrubs takes

rival's hanging baskets’ by Paul Sims from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/new/

article 28 July 2007 © Daily Mail 2007. Reproduced by perm ission. pp69, 87

& 154 Extracts from Yes, Prime Minister by A nthony Jay and Jonathan Lynn

© A nthony Jay & Jonathan Lynn published by BBC Books. Reproduced by

perm ission o f Random House Group Ltd and the Copyright agent: Alan Brodie

Representation Ltd, 6th floor, Fairgate House, 78 New Oxford Street, London

WE1A 1HB, info@ alanbrodie.com .

Sources: p45 w w v.tiniesonline.co.uk/tol/com m ent/colum nists/m inette_

m arrin/article2702726; p l41 How to be inimitable by George Mikes, Penguin

Books 1966, first published by Andre Deutsch © George Mikes 1960. p60

Writing home by Alan B ennett, Faber and Faber 1994. p62 Extract from an

article by John Peel, The Radio Times 2-8 Decem ber 2000. p l l 5 E xtract from

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-481129/Victory-Britains-metricmartyrs-Eur. pOO E xtract from http://ec.europa.eu/unitedkingdom /press/

eurom yths/m yths2 l_en.htm ; p l7 3 E xtract from The English by Jerem y

Paxm an, Penguin 1999. p l8 3 Extract from How to be an alien by George Mikes,

p i 34 Extract from ‘Liberal Sum m erhill tries discipline’ by Stan Griffiths and

Maurice C hittenden, The Sunday Times, 4 June 2006.

The publisher would like to thank the following fo r their kind permission to reproduce

copyright material: Cover im age courtesy Stockbyte/Getty Images. Alamy pp20

(Neil Holmes/Holmes Garden Photos), 22 (Charles the King walked fo r the last time

through the streets o f London 1649/The Print Collector), 25 (Julie W oodhouse/

Chatsworth), 39 (Tim Gainey), 45 (Lordprice Collection), 85 (Anne-Marie Palmer),

105 (Jim Wileman), i l l (Jack Sullivan), 119 (The Photolibraiy Wales), 124 (Jeff

Morgan), 129 (John Bond/Chapel), 129 (Robert Estall/Mosque), 130 (Gregory

Wrona), 139 (Brinkstock/M anchester University), 129 (Geophotos/Colchester

University), 129 (JMS/Keele University), 147 (Lifestyle), 149 (Tesco Generation

Banksy, Essex Road, London/Simon Woodcock), 156 (Allan Gallery), 162 (Alan

Francis), 164 (PhotoMax), 177 (David Lyons), 178 (David Askham), 181 (Mark

Hughes Photography), 183 (AdamJames), 191 (Nigel Tingle), 206 (Jon Arnold

Images Ltd), 209 Chris Howes/W ild Places Photography/rock), 210

(nagelestock.com), 214 (Tim Hill), 215 (Mary Evans Picture Library); BBC ©

pp51 (Frost Report), 102 (sw ingom eter), 107 (Dixon o f Dock Green), 122 (The

Vicar o f Dibley): Bridgem an A rt Library pp21 (Queen Elizabeth I in Coronation Robes

English School/National Portrait Gallery), p i 16 (The A rk Raleigh English

School/Private Collection), 209 (Skegness is So Bracing John Hassall/National

Railway M useum York); Corbis p p 8 (Peter Adams/Zefa), 99 (Owen Franken),

125 (Image 100), 129 (Michael Nicholson/Synagogue), 129 (Philippa Lewis/

Edifice/Sikh Temple), 189 (Peter Apraham ian); M aiy Evans Picture Libraiy

plO (Britannia and John Bull); Getty Images p p l2 (Southern Rock/harp), 12

(Richard Elliott/bag pipes), 13 (Dale Durfee), 17 (Charles Ernest ButlerfThe

B ridgem an Art Library), 19 (Hulton Archive/Handout), 26 (Portrait o f Queen

Victoria 1859 after Franz Xavier W interhalter/B ridgem an Art Library), 38

(Peter King/Hulton Archive), 52 (Photo and Co/Stone), 61 (Windsor & W ienhahn/

The Image Bank), 63 (Miki Duisterhof/Stock Food Creative), 68 (Sean H unter/

Dorling Kindersley RF), 72 (Michael Betts), 78 (Peter Macdiarmid), 80 (Adrian

Dennis/AFP), 82 (Keystone/Stringer/Hulton Archive), 83 (Ian Waldie), 98 (Leon

Neal/AFP/entry to hosue o f Lords), 128 (JeffJ Mitchell), 141 (Christopher

Furlong), 143 (Anthony Marsland), 146 (Dominic Burke), 180 (Matt Cardy),

184 (Gallo Images), 187 (STasker/Photonica), 193 (Ian Waldie), 195 (David

Rogers), 197 (Carl de Souza/ AFP), 207 (Karen Bleier/AFP), 213 (Jonathan

Knowles/St Patrick’s Day), 213 (Siegfried LaydafThe Im age Bank/Halloween);

Im pact Photos pp23 (Carolyn Clarke/Spectrum Colour Library); iStockphoto

p p llO (Anthony Baggett), 208 (StarFishDesign); N ational P ortrait Galleiy

pp21 (Henty WH Hans Holbein the Younger NPG 157); N ational Trust Photo

Library p64 (David Noton); OUP p p l4 (Eyewire), 15 (Digital Stock), 16

(Photodisc), 25 (Chris King/Nelson’s Column), 30 (Eyewire), 36 (Photodisc),

37 (Photodisc), 41 (Digital Vision), 47 (Mike Chinery), 48(Stockbyte). 58 (Jan

Tadeusz), 59 (Photodisc), 87 (Corel), 107 (Alamy/Police chase), 109 (Photodisc),

133 (Chris King), 139(Digital Vision/Oxford), 163 (Corel), 173 (Alchemy

M indworks Inc), 176 (Alchemy M indworks Inc), 188 (Picturesbyrob), 199

(Photodisc), 212 (Photodisc), 213 (Corel/New Year’s Day), 213 (Photodisc/Fire),

213 (Corbis/Digital Stock/Rem em brance Day), 213 (Purestock/Christm as Day);

Press Association p p 5 5 (NiallCarson/PAW ire/Empics), 92 (PAArchive), 93

(PA Archive), 98 (Empics/Black Rod), 120 (John Giles/Empics/Free Derry), 192

(Gareth Copley/PA Archive); Rex Features pp44 (Con Tanasiuk/Design Pics Inc),

77,102 (Peter Snow), 120 (Action Press/UFF), 142 (J K Press); Robert Harding

Picture Library p92 (Adam W oolfitt), T ransport for London p l 66 .

Logos by kind permission: The AA www.theaa.com , ASDA, Barclays pic, The

Conservative Party, The Daily Express (Northern & Shell Network), The Daily

Mail, Daily Mirror (c/o Mirrorpix), The Daily Star (Northern 81 Shell Network)

The Daily Telegraph, The G uardian c/o The Guardian News and Media Ltd 2008,

HSBC, The Independent, The Labour Party, The Liberal Democrats, Lloyds pic,

Marks & Spencer (http://corporate.m arksandspencer.com /), Morrisons, NHS

D epartm ent o f H ealth www.dh.gov.uk. The National Trust, The RAC, RBS The

Royal Bank o f Scotland, J Sainsbury pic. The Sun (c/o www.nisyndication.com),

The Times (c/o ww w.nisyndication.com ), W aitrose Ltd www.waitrose.com.

Illustrations by: Tabitha Macbeth p l l ; Peter Bull pp9, 28, 33, 34, 89, 91,113,

207; M ark McLaughlin p p l7 4 and 175.

4

Contents

Introduction

06 Political life

The public a ttitu d e to politics • The style o f

democracy • The constitution • The style o f politics •

The party system • The m odern situation

01 Country and people

Geographically speaking • P olitically speaking

The fo u r nations • The dom inance o f England

N ational loyalties

07 The monarchy

so

The appearance • The reality • The role o f the

monarch • The value o f the m onarchy • The future

02 History

15

Prehistory • The Roman period (4 3 -4 1 0 ) •

The Germanic invasions (4 1 0 -1 06 6 ) • The medieval

period (1 0 6 6 -1 4 5 8 ) • The sixteenth century •

The seventeenth century • The eighteenth century The nineteenth century • The tw entieth century

03 Geography

o f the m onarchy

08 The governm ent

The cabinet • The Prime M inister

service • Local governm ent

32

C lim ate • Land and settlem ent • The environm ent

and pollu tio n • London • Southern England •

The M idlands o f England • N orthern England •

Scotland • Wales • N orthern Ireland

04 Identity

69

85

The civil

09 Parliament

92

The atm osphere o f Parliam ent • An M P’s life

Parliam entary business • The pa rty system

in Parliament • The House o f Lords

43

Ethnic identity: the fo u r nations • O th e r ethnic

identities • The fam ily • Geographical identity •

Class • Men and women • Social and everyday

contacts • Religion and politics • Identity in

N o rthern Ireland • Being British • Personal identity:

a sense o f hum o u r

05 Attitudes

Stereotypes and change • English versus British •

A m u lticu ltu ra l society • Conservatism • Being

different • Love o f nature • Love o f animals •

Public-spiritedness and am ateurism • Form ality and

in fo rm a lity • Privacy and sex

58

10 Elections

99

The system • Formal arrangements • The campaign •

Polling day and election n ight • Recent results and

the future • M odern issues

11 The law

107

The police and the public • Crime and crim inal

procedure • The system o f justice • The legal

profession

12 International relations

113

British people and the rest o f the w o rld • The British

state and the rest o f the w o rld • T ransatlantic

relations • European relations • Relations inside

Great Britain • Great B ritain and N o rthern Ireland

CONTENTS

13 Religion

121

130

Historical background • M odern times: the education

debates • Style • School life • Public exams •

Education beyond sixteen

15 The econom y and

everyday life

141

20 Food and drink

Eating habits and attitudes • Eating o u t

A lcohol • Pubs

21 Sport and com petition

22 The arts

151

The im portance o f the national press • The tw o types

o f national newspaper • The characteristics o f the

national press: politics • The characteristics o f the

national press: sex and scandal • The BBC •

Television: organization • Television: style

17 Transport

183

190

A n ational passion • The social im p o rta nce

o fs p o r t • Cricket • Football • Rugby •

Anim als in s p o rt • O th e r sports • G am bling

Earning money: w o rkin g life • W o rk organizations

Public and private in d u stry • The d is trib u tio n o f

w ealth • Using money: finance and investment •

Spending money: shopping • Shop opening hours

16 The media

173

Houses, n o t flats • Private p roperty and public

p roperty • The im portance o f ‘ hom e’ • Individuality

and c o n fo rm ity • Interiors: the im portance

o f cosiness • O w ning and renting • Homelessness •

The future

Politics ■ Anglicanism • C atholicism • O ther

conventional C hristian churches • O th e r religions,

churches, and religious movements

14 Education

19 H ousing

5

161

On the road • Public tra n s p o rt in tow ns and cities

Public tra n s p o rt between towns and cities •

The channel tunnel • A ir and w ater

18 Welfare

The benefits system • Social services and charities •

The N ational Health Service • The medical profession

200

The arts in society • The characteristics

o f British arts and letters < Theatre and

cinema • M usic • W ords • The fine arts

23 Holidays and

special occasions

207

T ra d itio n al seaside holidays • Modern

holidays • Christmas • New Year • O th e r notable

annual occasions

Country and people

W h y is B r ita in ‘ G r e a t?

The o rig in o f the adjective

‘great’ in the name G reat B ritain

was n o t a piece o f advertising

(a lth o u g h m odern p o liticia n s

som etim es try to use it th a t

w ay!). It was firs t used to

distinguish it fro m the sm aller

area in France w hich is called

‘ B ritta n y ’ in m odern English.

This is a book about Britain. But what exactly is Britain? And who are the

British? The table below illustrates the problem. You m ight th in k that,

in international sport, the situation would be simple - one country,

one team. But you can see th at this is definitely not the case with Britain.

For each o f the four sports or sporting events listed in the table, there

are a different num ber o f national team s which m ight be described as

‘British’. This chapter describes how this situation has come about and

explains the many names th a t are used when people talk about Britain.

Geographically speaking

Lying off the north-west coast o f Europe, there are two large islands and

hundreds o f much smaller ones. The largest island is called Great Britain.

The other large one is called Ireland (G re a t B rita in a nd Ireland). There is no

agreem ent about w hat to call all o f them together (L o o k in g f o r a n a m e ).

Politically speaking

In this geographical area there are two states. One o f these governs

m ost o f the island o f Ireland. This state is usually called The Republic

o f Ireland. It is also called ‘Eire5(its Irish language name). Informally,

it is referred to as ju st ‘Ireland’ or ‘the Republic’.

The other state has authority over the rest o f the area (the whole

o f Great Britain, the north-eastern area o f Ireland and m ost o f the

smaller islands). This is the country th a t is the m ain subject o f this

book. Its official name is The United Kingdom o f Great Britain and

N orthern Ireland, b u t this is too long for practical purposes, so it is

usually known by a shorter name. At the Eurovision Song Contest, at

the United N ations and in the European parliam ent, for instance, it is

referred to as ‘the United Kingdom’. In everyday speech, this is often

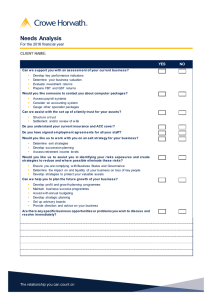

N a tio n a l te a m s in se le c te d s p o rts

England

Wales

Scotland

Northern Ireland

Republic o f Ireland

Ireland

O lym pics

G reat B ritain

C ricket

England and Wales

Scotland

Ireland

Rugby union

England

Scotland

Ireland

Football

England

Scotland

N o rth e rn Ireland

| Republic o f Ireland

POLITICALLY SPEAKING

shortened to cthe UK’ and in internet and email addresses it is ‘.uk’.

In other contexts, it is referred to as ‘Great Britain’. This, for example,

is the name you hear when a m edal winner steps onto the rostrum at

the Olympic Games. The abbreviation ‘GBP’ (Great Britain Pounds) in

international bank drafts is another example o f the use o f this name.

In w riting and speaking th a t is n o t especially form al or informal, the

nam e ‘Britain’ is used. The norm al everyday adjective, when talking

about som ething to do w ith the UK, is ‘British’ (W h y is B rita in ‘ G r e a t? ).

G re a t B rita in a n d Ire la n d

L o o k in g f o r a n a m e

It’s n o t easy to keep geography

and politics apart. Geographically

speaking, it is clear th a t Great

B ritain, Ireland and all those

smaller islands belong together. So

you w o u ld th in k there w ould be

a (single) name fo r them . D uring

the nineteenth and tw entieth

centuries, they were generally

called T h e British Isles'. But

most people in Ireland and some

people in Britain regard this name

as outdated because it calls to

mind the tim e when Ireland was

po litica lly dom inated by Britain.

SCOTLAND

So w h a t can we call these islands?

Am ong the names which have been

used are ‘The north-east A tlantic

archipelago’, T h e north-west

European archipelago’, cIONA’

(Islands o f the N orth A tlantic)

and simply T h e Isles’. But none o f

these has become widely accepted.

NORTHERN

IRELAND •Belfast

REPUBLIC

OF IRELAND

. 4EIRI-)

*

D u b lin

UNITED KINGDOM

OF GREAT BRITAIN AND

NORTHERN IRELAND

WALES

ENGLAND

London

200km

Channel

Islands

The m ost com m on term at

present is ‘Great B ritain and

Ireland’. But even this is not

strictly correct. It is n o t correct

geographically because it ignores

all the sm aller islands. And it is

n o t correct p o litica lly because

there are tw o small parts o f the

area on the maps w hich have

special po litica l arrangements.

These are the Channel Islands

and the Isle o f M an, w hich

are ‘crown dependencies’ and

n o t o fficia lly p a rt o f the UK.

Each has com plete internal

self-government, including its

own parliam ent and its own tax

system. Both are ‘ ruled’ by a

Lieutenant G overnor appointed

by the British government.

9

10

COUNTRY AND PEOPLE

The four nations

S o m e h is to r ic a l a n d p o e tic

n am es

Albion is a w ord used by poets

and songwriters to refer, in

different contexts, to England or

to Scotland o r to Great Britain as

a whole. It comes from a Celtic

w ord and was an early Greek

and Roman name fo r Great

Britain. The Romans associated

Great Britain w ith the Latin word

‘albus’, meaning white. The white

chalk cliffs around Dover on

the English south coast are the

first land form ations one sights

when crossing the sea from the

European mainland.

Britannia is the name th a t the

Romans gave to th e ir southern

B ritish province (w h ich covered,

approxim ately, the area o f

present-day England and Wales).

It is also the name given to the

fem ale em b o d im e n t o f B rita in ,

always shown w earing a helmet

and h o ld in g a trid e n t (the

symbol o f pow er over the sea),

hence the p a trio tic song which

begins ‘ Rule B ritan n ia, B ritannia

rule the waves’. The figure o f

B ritann ia has been on the reverse

side o f m any British coins fo r

more than 300 years.

People often refer to Britain by an o th er name. They call it

‘E ngland5. But this is n o t correct, and its use can make some people

angry. England is only one o f ‘the four n atio n s’ in this p a rt o f the

world. The others are Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Their political

unification was a gradual process th a t took several h u n d red years

(see chapter 2). It was com pleted in 1800 w hen the Irish parliam ent

was joined w ith the parliam ent for England, Scotland, and Wales

in W estminster, so th a t the whole area became a single state - the

U nited K ingdom o f G reat Britain and Ireland. However, in 1922,

m ost o f Ireland became a separate state (see chapter 12).

At one time, culture and lifestyle varied enorm ously across the

four nations. The d o m in an t culture o f people in Ireland, Wales

and H ighland Scotland was Celtic; th a t o f people in England and

Lowland Scotland was Germanic. This difference was reflected in

the languages they spoke. People in the Celtic areas spoke Celtic

languages; people in the G erm anic areas spoke G erm anic dialects

(including the one which has developed into m odern English). The

nations also tended to have different economic, social, and legal

systems, and they were independent o f each other.

O t h e r sig n s o f n a tio n a l id e n tity

Briton is a w o rd used in o fficia l

contexts and in w ritin g to

describe a citizen o f the U nited

K ingdom . ‘A n cie n t B rito n s ’ is

the name given to the people

w ho lived in southern B ritain

before and d u rin g the Roman

o c cu p a tio n (A D 4 3 -4 1 0 ). T h e ir

heirs are th o u g h t to be the Welsh

and th e ir language has developed

in to the m odern Welsh language.

Caledonia, Cam bria and Hibernia

were the Roman names fo r

S cotland, W ales and Ireland

respectively. The w ords are

c o m m o n ly used to d a y in scholarly

classifications (fo r example, the

type o f English used in Ireland

is som etim es called ‘ H ib e rn o English’ and there is a division

o f geological tim e know n as

‘the C am brian p e rio d ’ ) and fo r

the names o f o rg anizations (fo r

example, ‘Glasgow C a le d o n ia n ’

U niversity).

Erin is a p oetic name fo r Ireland.

The Emerald Isle is a n o th e r way

o f referring to Ireland, evoking the

lush greenery o f its co untryside.

John Bull (see below) is a fictional

character w ho is supposed to personify

Englishness and certain English virtues.

(He can be compared to Uncle Sam in

the USA.) He appears in hundreds o f

nineteenth century cartoons. Today,

somebody dressed as him often appears at

football o r rugby matches when England

are playing. His appearance is typical o f

an eighteenth century country gentleman,

evoking an idyllic rural past (see chapter 5).

THE FOUR NATIONS

Today, these differences have become blurred, b u t they have n o t

com pletely disappeared. A lthough there is only one governm ent

for th e whole o f Britain, and everybody gets the same passport

regardless o f where in B ritain they live, many aspects o f governm ent

are organized separately (and som etim es differently) in the four

p arts o f the U nited Kingdom. Moreover, Welsh, Scottish and

Irish people feel their identity very strongly. T h a t is why they have

separate team s in m any kinds o f in tern atio n al sport.

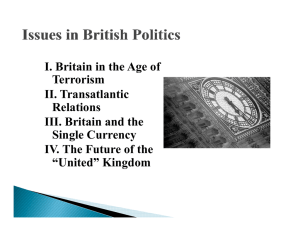

Id e n tify in g s y m b o ls o f th e f o u r n a tio n s

England

-H

Flag

St. George’s

Cross

Wales

Scotland

Ireland

St. A ndrew ’s

Cross

St. Patrick’s

Cross

iM i

Dragon o f

C adw allader

Lion Ram pant

Plant

rose

le e k/d a ffo d il1

thistle

Republic o f

Ireland

shamrock

□

C o lo u r2

Patron saint

St. George

St. David

St. Andrew

St. Patrick

S aint’s day

23 April

1 March

30 November

17 March

1 there is some disagreement among Welsh people as to which is the real national

plant, b u t the leek is the m ost well-known

2 as typically w orn by sports teams o fth e different nations

11

O th e r to k e n s o f n a tio n a l id e n tity

The fo llo w in g are also associated

by British people w ith one o r

more o fth e fo u r nations.

Surnames

The prefix ‘ M ac’ o r ‘M e’ (such as

M cC all, MacCarthy, M acD onald)

is Scottish o r Irish. The prefix

‘O ’ (as in O ’ Brien, O ’C onnor) is

Irish. A large num ber o f surnames

(fo r example, Evans, Jones,

M organ, Price, W illia m s) suggest

Welsh o rigin. The m ost com m on

surname in both England and

Scotland is ‘S m ith’.

First names for men

The Scottish o f ‘John’ is ‘ Ian’ and

its Irish form is ‘Sean’, although

all three names are com m on

th ro u g h o u t Britain. Outside their

own countries, there are also

nicknames fo r Irish, Scottish and

Welsh men. For instance, Scottish

men are sometimes known and

addressed as ‘Jock’, Irishmen

are called ‘ Paddy’ o r ‘ M ick’ and

Welshmen as ‘ Dai’ o r ‘Taffy’. If the

person using one o f these names is

n o t a friend, and especially i f it is

used in the plural (e.g. ‘ M icks’), it

can sound insulting.

Clothes

The kilt, a s k irt w ith a ta rta n

pattern w orn by men, is a

very w ell-known symbol o f

Scottishness (though it is hardly

ever w o rn in everyday life).

C h a ra c te ris tic s

There are certain stereotypes

o f national character w hich

are well known in B ritain. For

instance, the Irish are supposed

to be great talkers, the Scots

have a reputation fo r being

careful w ith money and the

Welsh are renowned fo r th e ir

singing ability. These are, o f

course, only caricatures and not

reliable descriptions o f individual

people from these countries.

Nevertheless, they indicate some

slight differences in the value

attached to certain kinds o f

behaviour in these countries.

12

COUNTRY AND PEOPLE

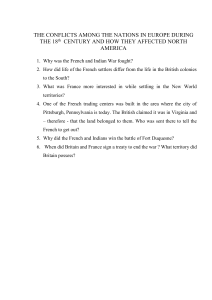

P op u la tio n s in 2 0 0 6

N orthern

Ireland

Scotland

m m m

©

Wales

England

(figures in m illions)

UK Total

60.6

These figures are estimates

provided by the Office fo r

N ational Statistics (England and

Wales), the General Register Office

fo r Scotland and the N orthern

Ireland Statistics and Research

Agency. In the tw enty-first century,

the to ta l population o f Britain

has risen by about a quarter o f a

m illion each year.

M u s ic a l in s tru m e n ts

The harp is an em blem o f b oth

Wales and Ireland. Bagpipes

are regarded as d istin ctive ly

S cottish, although a sm aller

type is also used in tra d itio n a l

Irish music.

(Right) A harp.

(Far right) A Scottish bagpipe.

The dom inance o f England

There is, perhaps, an excuse for the people who use the word

‘E ngland’ w hen they m ean ‘B ritain’. It cannot be denied th a t the

d o m in an t culture o f Britain today is specifically English. The system

o f politics th a t is used in all four nations today is o f English origin,

and English is the m ain language o f all four nations. Many aspects

o f everyday life are organized according to English custom and

practice. But the political unification o f B ritain was n o t achieved by

m u tu al agreem ent. O n the contrary, it happened because England

was able to assert her econom ic and m ilitary power over the other

three nations (see chapter 2).

Today, English d o m in atio n can be detected in the way in which

various aspects o f B ritish public life are described. For example, the

supply o f m oney in B ritain is controlled by the Bank o f England

(there is no such th in g as a ‘Bank o f B ritain’). A nother example

is the nam e o f the present m onarch. She is universally know n as

‘Elizabeth II’, even th o u g h Scotland and N o rth e rn Ireland have

never had an ‘Elizabeth I’. (Elizabeth I o f England an d Wales ruled

from 1553 to 1603). The com m on use o f the term ‘A nglo’ is a

fu rth er indication. (The Angles were a G erm anic tribe who settled

in England in the fifth century. The word ‘E ngland’ is derived

from their name.) W hen newspapers and the television news talk

ab o u t ‘Anglo-American relations’, they are talking ab o u t relations

between the governm ents o f B ritain and the USA (and n o t ju st

England and the USA).

In addition, there is a tendency in the names o f publications and

organizations to portray England as the norm and other parts o f

Britain as special cases. Thus there is a specialist newspaper called

NATIONAL LOYALTIES

the Times Educational Supplement, b u t also a version o f it called the

Times Educational Supplement (Scotland). Similarly, the um brella

organization for employees is called the ‘Trades U nion C ongress’,

b u t there is also a ‘Scottish Trades U nion C ongress’. W hen

som ething pertains to England, this fact is often n o t specified in

its name; when it pertains to Wales, Scotland or N o rth ern Ireland,

it always is. In this way, these parts o f B ritain are presented as

som ething ‘o th e r’.

13

C a re fu l w it h t h a t a d d re s s !

W hen you are addressing a letter

to somewhere in B ritain, d o n o t

w rite anything like ‘ E dinburgh,

E ngland’ o r ‘ C ardiff, England’.

You should w rite ‘ Edinburgh,

S co tla n d ’ and ‘ C ardiff, W ales’

- o r ( i f you feel ‘S co tla n d’ and

‘ W ales’ are n o t recognizable

enough) w rite ‘ Great B rita in ’ or

‘ U nited K in g d o m ’ instead.

N ational loyalties

The dom inance o f England can also be detected in the way th a t many

English people don’t bother to distinguish between ‘Britain’ and

‘England’. They write ‘English’ next to ‘nationality’ on forms when

they are abroad and talk about places like Edinburgh as if it was p art

o f England.

Nevertheless, w hen you are talking to people from Britain, it is safest

to use ‘B ritain’ when talking ab o u t where they live and ‘B ritish’

as the adjective to describe their nationality. This way you will

be less likely to offend anyone. It is, o f course, n o t w rong to talk

ab o u t ‘people in England’ if th a t is w hat you m ean - people who

live w ithin the geographical boundaries o f England. After all, m ost

B ritish people live there ( P o p u la tio n s in 2 0 0 6 ). But it should always

be rem em bered th a t England does n o t make up the whole o f the UK

(C a re fu l w ith t h a t a d d re s s !).

T h e p e o p le o f B rita in

w hite other

Asian Indian

Asian Pakistani

mixed ethnicity

w hite Irish

black Caribbean

black African

black Bangladeshi

% o f UK population

in 2001

Chinese

Asian other

One o fth e questions in the 2001 census o fth e UK was ‘W h a t

is your ethnic group?’ and the categories above were offered as

choices. Here are some o fth e results, listed in order o f size.

As you can see, a b o u t one in nine people identified themselves

as som ething o th e r than ‘w hite B ritish’. The largest category

was ‘w hite o th e r’, b u t these people were from a variety o f

places and m any were only te m p o ra rily resident in B ritain. As

a result, they do n o t form a single identifiable com m unity. (For

these and o th e r reasons, the same is largely true o f those in

the w hite Irish and black African categories.) By fa r the largest

recognizable ethnic grouping was form ed by people whose

ethnic roots are in the Indian subcontinent (Indian, Pakistani

and Bangladeshi in the ch a rt); together they made up more

than tw o m illion people. The o ther established, recognizable

ethnic group in B ritain were black Caribbeans (a little over h a lf

a m illio n people).

W h a t this c h a rt does n o t show are all the people w ho came

to Britain from eastern Europe (especially Poland) in the years

2004-2007. T h e ir numbers, estimated between three quarters

o f a m illio n and one m illio n , represent the largest single wave

o f im m igration to Britain in more than 300 years. However, it

is n o t clear at this tim e how many w ill set up home in Britain.

A nother p o in t abo u t the people o f Britain is w o rth noting. Since

the 1980s, more people im m igrate to Britain than emigrate

from it every year. A quarter o f all babies born in Britain are

born to at least one foreign-born parent. A t the same tim e,

emigration is also very high. The people o f Britain are changing.

14

COUNTRY AND PEOPLE

There has been a long history o f m igration from Scotland, Wales

and Ireland to England. As a result, there are millions o f people who

live in England b u t who would never describe themselves as English

(or at least n o t as only English). They may have lived in England

all their lives, b u t as far as they are concerned they are Scottish or

Welsh or Irish - even if, in the last case, they are citizens o f Britain

and not o f Eire. These people su p p o rt the country o f their parents or

grandparents rather th an England in sporting contests. They would

also, given the chance, play for th a t country rather th an England.

The same often holds true for the further millions o f British citizens

whose family origins lie outside Britain or Ireland. People o f Caribbean

or south Asian descent, for instance, do n o t m ind being described as

‘British’ (many are proud o f it), b u t many o f them would n o t like to be

called ‘English’ (or, again, not only English). And whenever the West

Indian, Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi cricket team plays against

England, it is usually n o t England th a t they support!

There is, in fact, a complicated division o f loyalties am ong many

people in Britain, and especially in England. A black person whose

family are from the Caribbean will passionately support the West

Indies when they play cricket against England. But the same person is

quite happy to support England ju st as passionately in a sport such as

football, which the West Indies do not play. A person whose family are

from Ireland b u t who has always lived in England w ould w ant Ireland

to beat England at football b u t would w ant England to beat (for

example) Italy ju st as much.

This crossover o f loyalties can work the other way as well. English

people do n o t regard the Scottish, the Welsh or the Irish as ‘foreigners’

(or, at least, n o t as the same kind o f foreigner as other foreigners!). An

English com m entator o f a sporting event in which a Scottish, Irish

or Welsh team is playing against a team from elsewhere in the world

tends to identify w ith th a t team as if it were English.

Flag

The Union flag, often known as

the ‘ U n io n ja c k ’, is the national

flag o fth e UK. It is a com bination

o fth e cross o f St. George, the

cross o f St. Andrew and the cross

o fS t. Patrick.

QUESTIONS

1 W hich o f the names suggested in this chapter for the group o f

islands off the north-w est coast o f Europe do you th in k would be

the best? Can you th in k o f any others?

2 Is there the same kind o f confusion o f and disagreem ent about

names in your country as there is in Britain and Ireland? How does

this happen?

3 Think o f the well-known symbols and tokens o f nationality in your

country. Are they the same types o f real-life objects (e.g. plants and

clothes) th a t are used in Britain?

4 In the British government, there are ministers with special

responsibility for Scotland, Wales and N orthern Ireland, b u t there is

no m inister for England. Why do you th in k this is?

15

02

History

Prehistory

Two th o u san d /years ago

o there was an Iron Age

o> Celtic culture

th ro u g h o u t the north-w est E uropean islands. It seems th a t the

Celts had interm ingled w ith the peoples who were there already; we

know th a t religious sites th a t h ad been b uilt long before th eir arrival

co ntinued to be used in Celtic times.

For people in B ritain today, the chief significance o f the prehistoric

period is its sense o f mystery. This sense finds its focus m o st easily

in the astonishing m on um ental architecture o f this period, the

rem ains o f which exist th ro u g h o u t the country. W iltshire, in so u th ­

w estern England, has two spectacular examples: Silbury Hill, the

largest burial m o u n d in Europe, and Stonehenge (S to n e h e n g e ). Such

places have a special im portance for some people w ith inclinations

towards mysticism and esoteric religion. For example, we know th a t

Celtic society had a priestly caste called the D ruids. Their nam e

survives today in the O rder o f Bards, Ovates, and D ruids.

S to n e h e n g e

Stonehenge was b u ilt on Salisbury

Plain some tim e between 5,000

and 4,300 years ago. It is one o f

the m ost fam ous and mysterious

archaeological sites in the w orld.

One o f its mysteries is how it

was ever b u ilt at all w ith the

technology o fth e tim e (some o f

the stones come from over 200

miles away in Wales). A nother is

its purpose. It appears to function

as a kind o f astronomical clock

and we know it was used by the

Druids fo r ceremonies marking

the passing o f the seasons. It

has always exerted a fascination

on the British im agination, and

appears in a number o f novels,

such as Thom as H ardy’s Tess o f

the D ’Urbervilles.

These days, it is n o t only o f

interest to tourists b u t is also

held in special esteem by certain

m inority groups. It is now fenced

o ff to protect it from damage.

16

HISTORY

The R om an period (43-410)

The Roman province o f B ritannia covered m ost o f present-day

England and Wales, where the Romans im posed their own way o f life

and culture, m aking use o f the existing Celtic aristocracy to govern

and encouraging them to adopt Rom an dress and the Latin language.

They never went to Ireland and exerted an influence, w ithout actually

governing there, over only the so u th ern p art o f Scotland. It was

durin g this tim e th a t a Celtic tribe called the Scots m igrated from

Ireland to Scotland, where, along with another tribe, the Piets, they

became opponents o f the Romans. This division o f the Celts into

those who experienced Roman rule (the Britons in England and Wales)

and those who did n o t (the Gaels in Ireland and Scotland) may help

to explain the emergence o f two distinct branches o f the Celtic group

o f languages.

H a d r ia n ’ s W a ll

H adrian’s Wall was b u ilt by the

Romans in the second century

across the northern border o f

their province o f Britannia (which

is nearly the same as the present

English-Scottish border) in order

to protect it from attacks by the

Scots and the Piets.

The remarkable thing about the Romans is that, despite their long

occupation o f Britain, they left very little behind. To many other parts

o f Europe they bequeathed a system o f law and adm inistration which

forms the basis o f the m odern system and a language which developed

into the m odern Romance family o f languages. In Britain, they left

neither. Moreover, m ost o f their villas, baths and temples, their

impressive network o f roads, and the cities they founded, including

Londinium (London), were soon destroyed or fell into disrepair.

Almost the only lasting reminders o f their presence are place names

like Chester, Lancaster and Gloucester, which include variants o f the

Latin word castra (a military camp).

The Germanic invasions (410-1066)

The Roman occupation had been a m atter o f colonial control rather

th an large-scale settlement. But during the fifth century, a num ber

o f tribes from the European m ainland invaded and settled in large

num bers. Two o f these tribes were the Angles and the Saxons. These

Anglo-Saxons soon had the south-east o f the country in their grasp. In

the west, their advance was temporarily halted by an army o f (Celtic)

Britons under the com m and o f the legendary King A rthur (K in g

A rth u r ) . Nevertheless, by the end o f the sixth century, they and their

S om e im p o r t a n t d a te s in B ritis h h is to r y

55 BC

The Roman general

Julius Caesar lands

in B ritain w ith an expeditionary force,

wins a battle and leaves. The firs t ‘da te ’

in p o p u la r British history.

AD 43

The Romans come

to stay.

f

Queen Boudicca (o r Boadicea)

o fth e Iceni tribe leads a

bloody revolt against the Roman

occupation. It is suppressed. There

is a statue o f Boadicea, made in the

nineteenth century, outside the Houses

o f Parliament, which has helped to keep

her m em ory alive.

v/ JL

410

432

597

The Romans leave B ritain

St. Patrick converts

Ireland to Christianity.

St. Augustine arrives in

B ritain and establishes his

headquarters at Canterbury.

THE GERMANIC INVASIONS (410-1066)

17

way o f life predom inated in nearly all o f present-day England. Celtic

culture and language survived only in present-day Scotland, Wales

and Cornwall.

The Anglo-Saxons had little use for towns and cities. But they had a

great effect on the countryside, where they introduced new farming

m ethods and founded the thousands o f self-sufficient villages which

form ed the basis o f English society for the next th o u san d or so years.

W hen they came to Britain, the Anglo-Saxons were pagan. D uring

the sixth and seventh centuries, C hristianity spread th ro u g h o u t

B ritain from two different directions. By the time it was introduced

into the south o f England by the R om an m issionary St. A ugustine,

it had already been introduced into Scotland and n o rth e rn

England from Ireland, which had become C hristian m ore th a n 150

years earlier. A lthough Rom an C hristianity eventually took over

everywhere, the Celtic m odel persisted in Scotland and Ireland for

several h un d red years. It was less centrally organized and had less

need for a strong m onarchy to su p p o rt it. This partly explains why

b o th secular and religious power in these two countries continued

to be both more locally based and less secure th ro u g h o u t the

medieval period.

K in g A r t h u r

King A rth u r is a wonderful

example o fth e distortions o f

p opular history. In folklore and

myth (and on film ), he is a great

English hero, and he and his

Knights o fth e Round Table are

regarded as the perfect example o f

medieval n o b ility and chivalry. In

fact, he lived long before medieval

times and was a Romanized Celt

trying to hold back the advances

o fth e Anglo-Saxons - the very

people who became ‘the English’ !

B ritain experienced another wave o f Germ anic invasions in the

eighth century. These invaders, know n as Vikings, N orsem en or

Danes, came from Scandinavia. In the n in th century they conquered

and settled the islands around Scotland and some coastal regions

o f Ireland. Their conquest o f England was halted when they were

defeated by King Alfred o f the Saxon kingdom o f Wessex (K in g A lfre d )

As a result, their settlem ent was confined m ostly to the n o rth and

east o f the country.

However, the cultural differences between Anglo-Saxons and Danes

were comparatively small. They led roughly the same way o f life and

spoke different varieties o f the same Germ anic tongue. Moreover,

the Danes soon converted to Christianity. These sim ilarities made

political unification easier, an d by the end o f the ten th century,

England was a united kingdom w ith a Germ anic culture throughout.

M ost o f Scotland was also united by this time, at least in name, in a

(Celtic) Gaelic kingdom .

^ Q k ^ 2 The great m onastery o f

/

\ J Lindisfarne on the east

coast o f B ritain is destroyed by

Vikings and its monks killed.

Q

Edgar, a grandson o f Alfred,

/ kJ becomes king o f nearly all o f

present-day England and fo r the firs t tim e

the name ‘ England1is used.

* BC means ‘ before C h ris t’. All the o th e r dates

are A D (in Latin anno dotnini), w hich signifies ‘year

o f O u r L ord ’. Some m odern h istorians use the

n o ta tio n BCE ( ‘ Before C om m o n Era’) and CE

( ‘C om m o n Era’ ) instead.

0 ^ 7 0

The Peace o f Edington

O / O

p a rtitio n s the

G erm anic terrtories between King

A lfred’s Saxons and the Danes.

18

HISTORY

K in g A lfre d

The m edieval period (1066-1458)

King Alfred was n o t only an able

w a rrio r b u t also a dedicated

scholar (the only English monarch

fo r a long tim e afterw ards w ho

was able to read and w rite) and a

wise ruler. He is known as ‘Alfred

the G reat’ - the only monarch in

English history to be given this title.

He is also popularly known fo r the

story o fth e burning o fth e cakes.

The successful N orm an invasion o f England (1066) b ro u g h t B ritain

in to the m ainstream o f w estern European culture. Previously, m ost

links h ad been w ith Scandinavia. Only in Scotland did this link

survive, the w estern isles (until the 13th century) and the n o rth e rn

islands (until the fifteenth century) rem aining u n d er the control o f

Scandinavian kings. T h ro u g h o u t this period, the English kings

also owned land on the co n tin en t and were often at war w ith the

French kings.

W hile he was w andering around

his co u n try organizing resistance

to the Danish invaders, Alfred

travelled in disguise. On one

occasion, he stopped a t a

w o m a n ’s house. The wom an

asked him to w atch some cakes

th a t were cooking to see th a t they

did n o t burn, w hile she w ent o ff

to get food. Alfred became lost

in th o u g h t and the cakes burned.

When the w om an returned, she

shouted angrily at Alfred and sent

him away. Alfred never to ld her

th a t he was her king.

Unlike the Germanic invasions, the N orm an invasion was small-scale.

There was no such thing as a N orm an area o f settlement. Instead, the

N orm an soldiers who had invaded were given the ownership o f land and o f the people living on it. A strict feudal system was imposed.

Great nobles, or barons, were responsible directly to the king; lesser

lords, each owning a village, were directly responsible to a baron.

Under them were the peasants, tied by a strict system o f m utual duties

and obligations to the local lord, and forbidden to travel w ithout his

permission. The peasants were the English-speaking Saxons. The lords

and the barons were the French-speaking Norm ans. This was the start

o f the English class system (L a n g u a g e a n d so cia l class).

1066

This is the most famous date in

English history. On 14 O ctober o f

th a t year, an invading army from

N orm andy defeated the English at

the Battle o f Hastings. The battle

was close and extremely bloody.

A t the end o f it, m ost o fth e best

w arriors in England were dead,

including their leader, King Harold.

On Christmas day th a t year, the

N orm an leader, Duke W illia m o f

N orm andy, was crowned king o f

England. He is known in popular

history as ‘W illia m the C onqueror’

and the date is remembered as

the last time th a t England was

successfully invaded.

1066

The Battle o f Hastings.

O

King W illia m ’s

l U O O

o fficia ls com plete

the Dom esday Book, a very

detailed, village-by-village record

o fth e people and th e ir possessions

th ro u g h o u t his kingdom .

The system o f strong governm ent which the N orm ans introduced

made the A nglo-N orm an kingdom the m ost powerful political force

in Britain and Ireland. N ot surprisingly therefore, the au th o rity

o f the English m onarch gradually extended to other parts o f these

islands in the next 250 years. By the end o f the th irtee n th century,

a large p art o f eastern Ireland was controlled by Anglo-N orm an

lords in the nam e o f their king an d the whole o f Wales was under

his direct rule (at which time, the custom o f nam ing the m onarch's

eldest son the 'Prince o f Wales’ began). Scotland m anaged to rem ain

politically independent in the medieval period, b u t was obliged to

fight occasional wars to do so.

The cultural story o f this period is different. In the 250 years after

the N orm an Conquest, it was a Germanic language, Middle English,

and n o t the N orm an (French) language, which had become the

dom inant one in all classes o f society in England. Furtherm ore, it was

the Anglo-Saxon concept o f com m on law, and not Roman law, which

form ed the basis o f the legal system.

1170

The m u rd e r o f Thom as

Becket, the A rchbishop o f

Canterbury, by soldiers o f King Henry II.

Becket becomes a p o p u la r m a rtyr and his

grave is visited by pilgrim s fo r hundreds

o f years. The Canterbury Tales, w ritte n by

Geoffrey Chaucer in the fourteenth century,

recounts the stories to ld by a fictio n a l group

o f pilgrim s on their way to Canterbury.

1171

The N orm an baron

known as Strongbow

and his follow ers settle in Ireland.

THE MEDIEVAL PERIOD (1066-1458)

19

Despite English rule, n o rthern and central Wales was never settled in

great num bers by Saxons or N ormans. As a result, the (Celtic) Welsh

language and culture rem ained strong. Eisteddfods, national festivals

o f Welsh song and poetry, continued th ro u g h o u t the medieval period

and still continue today. The Anglo-Norman lords o f Ireland rem ained

loyal to the English king but, despite laws to the contrary, mostly

adopted the Gaelic language and customs.

The political independence o f Scotland did not prevent a gradual

switch to English language and custom s in the lowland (southern)

p a rt o f the country. Many Anglo-Saxon aristocrats had fled there

after the N orm an conquest. In addition, the Celtic kings saw th a t the

adoption o f an A nglo-N orm an style o f governm ent w ould strengthen

royal power. By the end o f this period, a cultural split had developed

between the lowlands, where the way o f life and language was sim ilar

to th a t in England, and the highlands, where Gaelic culture and

language prevailed - and where, due to the m oun tain o u s terrain, the

au th o rity o f the Scottish king was hard to enforce.

It was in this period th a t Parliam ent began its gradual evolution

into the democratic body which it is today. The word ‘parliam ent’,

which comes from the French word parler (to speak), was first used in

England in the thirteenth century to describe an assembly o f nobles

called together by the king.

R o b in H o o d

L a n g u a g e a n d s o c ia l class

Robin H ood is a legendary fo lk hero.

King Richard I (1 1 8 9 -9 9 ) spent m ost

o f his reign fig h tin g in the ‘crusades’

(the wars between C hristians

and M uslim s in the M id d le East).

M eanw hile, England was governed

by his b ro th e rjo h n , w h o was

u n p o p u la r because o f all the taxes

he im posed. A ccording to legend,

Robin H ood lived w ith his band o f

‘ m erry m en’ in S herw ood Forest

outside N o ttin g h a m , stealing from

the rich and giving to the poor. He

was co n sta n tly hunted by the local

sh e riff (the royal representative) b u t

was never captured.

■i

-i £ An alliance o f aristocracy, church

JL Z / A .

and merchants force K ingjohn to

agree to the Magna Carta (Latin meaning ‘Great

C harter’ ), a docum ent in which the king agrees

to fo llo w certain rules o f government. In fact,

n eitherjoh n n o r his successors entirely followed

them , b u t the Magna C arta is remembered as

the first time a m onarch agreed in w ritin g to

abide by form al procedures.

As an example o f the class

d istin ctio n s introduced in to

society a fte r the N orm an

invasion, people ofte n p o in t to

the fa c t th a t m odern English

has tw o w ords fo r the larger

farm anim als: one fo r the living

anim al (cow, pig, sheep) and

a n o th e r fo r the anim al you eat

(beef, p o rk, m u tto n ). The fo rm e r

set come fro m Anglo-Saxon, the

la tte r fro m the French th a t the

N orm ans b ro u g h t to England.

O n ly the N orm ans n o rm a lly ate

m eat; the p o o r Anglo-Saxon

peasants did n o t!

'|

^7 ^

Llewellyn, a Welsh

- L jL l /

prince, refuses

to subm it to the authority o fth e

English monarch.

1295

- i ^ Q A The Statute o f

-L

I Wales puts the

whole o f th a t country under the

control o fth e English monarch.

■1 ■ I ^ Q A fte r several years o f w ar

-L

L j O between the Scottish and

English kingdoms, Scotland is recognized

as an independent kingdom.

The Model Parliament sets

the pattern fo r the future

by including elected representatives from

urban and rural areas.

20

HISTORY

T h e W a rs o f t h e Roses

T h e sixteenth cen tu ry

D uring the fifteenth century, the

power o fth e greatest nobles, who

had their own private armies,

meant th a t constant challenges to

the position o fth e monarch were

possible. These power struggles

came to a head in the Wars o f

the Roses, in which the nobles

were divided into tw o groups,

one supporting the House o f

Lancaster, whose symbol was a red

rose, the other the House o f York,

whose symbol was a white rose.

Three decades o f alm ost continual

w a r ended in 1485, when Henry

T udor (Lancastrian) defeated and

killed Richard III (Yorkist) at the

Battle o f Bosworth Field.

In its first outbreak in the m iddle o f the fo u rteen th century, bubonic

plague (known in England as the Black Death) killed about a third

o f the po p u latio n o f G reat Britain. It periodically reappeared for

another 300 years. The shortage o f labour which it caused, and the

increasing im portance o f trade and towns, weakened the traditional

ties between lord and peasant. At a higher level o f feudal structure,

the power o f the great barons was greatly weakened by in-fighting

O f f w ith his h e a d !

Being an im p o rta n t person in the

sixteenth century was n o t a safe

position. The T u d o r monarchs

were disloyal to th e ir officials

and merciless to any nobles w ho

opposed them . M ore than h a lf

o fth e m ost fam ous names o fth e

period finished th e ir lives by being

executed. Few people w ho were

taken through T ra ito r’s Gate (see

below) in the Tower o f London

came o u t again alive.

(T h e W a rs o f t h e Roses).

Both these developments allowed English monarchs to increase

their power. The Tudor dynasty (1485-1603) established a system o f

governm ent departm ents staffed by professionals who depended for

their position on the monarch. The feudal aristocracy was no longer

needed for im plem enting governm ent policy. It was needed less for

making it too. O f the traditional two 'H ouses’ o f Parliament, the Lords

and the Com mons, it was now more im p o rtan t for m onarchs to get

the agreem ent o f the Com m ons for their policies because th a t was

where the newly powerful m erchants and landowners were represented.

Unlike in m uch o f the rest o f Europe, the im m ediate cause o f the rise

o f Protestantism in England was political and personal rather than

doctrinal. The King (H e n ry V III) w anted a divorce, which the Pope

would n o t give him. Also, by m aking him self head o f the 'Church

o f England’, independent o f Rome, all church lands came under his

control and gave him a large new source o f income.

This rejection o f the Roman Church also accorded with a new spirit

o f patriotic confidence in England. The country had finally lost any

realistic claim to lands in France, thus becoming more consciously

a distinct 'island n atio n ’. At the same time, increasing European

exploration o f the Americas m eant th a t England was closer to

the geographical centre o f western civilization instead o f being,

as previously, on the edge o f it. It was in the last quarter o f this

adventurous and optim istic century th a t Shakespeare began w riting

his famous plays, giving voice to the m odern form o f English.

It was therefore patriotism as m uch as religious conviction th a t had

caused Protestantism to become the majority religion in England by

the end o f the century. It took a form known as Anglicanism, n o t so

very different from Catholicism in its organization and ritual. But in

•i

JT

A

The A c t o f Supremacy

■" declares H enry VIII to

be the supreme head o fth e church

in England.

1536

The a d m in istra tio n o f

governm ent and law in

Wales is reformed so th a t it is exactly

the same as it is in England.

1 C ^ Q

An English

JL

O

language version o f

the Bible replaces Latin bibles in

every church in the land.

*t £

The Scottish p arlia m e n t

abolishes the a u th o rity o f

the Pope and fo rb id s the Latin mass.

JL

\J

1580

Sir Francis Drake

completes the first voyage

round the w orld by an Englishman.

THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

21

the lowlands o f Scotland, it took a more idealistic form. Calvinism,

with its strict insistence on simplicity and its dislike o f ritual and

celebration became the dom inant religion. It is from this date th a t the

stereotype image o f the dour, thrifty Scottish developed. However, the

highlands rem ained Catholic and so further widened the g u lf between

the two parts o f the nation. Ireland also remained Catholic. There,

Protestantism was identified with the English, who at th a t tim e were

making further attem pts to control the whole o f the country.

H e n ry V III

Henry VIII is one o f the m ost wellknown m onarchs in English history,

chiefly because he to o k six wives d u rin g

his life. He has the p o p u la r image

o f a bon viveur. There is much tru th

in this re p u ta tio n . He was a natural

leader b u t n o t really interested in the

day-to -d a y ru n n in g o f governm ent

and this encouraged the beginnings

o f a professional bureaucracy. It was

d u rin g his reign th a t the re fo rm a tio n

to o k place. In the 1 530s, H enry used

P arliam ent to pass laws w hich swept

away the pow er o f the Roman Church

in England. However, his quarrel w ith

Rome was n o th in g to do w ith d octrine.

It was because he w anted to be free

to m a rry again and to a p p o in t w ho

he wished as leaders o fth e church in

England. Earlier in the same decade, he

had had a law passed w hich dem anded

com plete adherence to C atholic

b e lie f and practice. He had also

previously w ritte n a polem ic against

P rotestantism , fo r w hich the pope gave

him the title Fidei Defensor (defender o f

the fa ith ). The in itia ls F.D. still appear

on British coins today.

E liz a b e th I

Elizabeth I, daughter o f Henry VIII, was

the firs t o f three long-reigning queens

in British history (the other tw o are

Queen V icto ria and Queen Elizabeth II).

D uring her long reign she established,

by skilful diplom acy, a reasonable

degree o f internal stability in a firm ly

P rotestant England, allow ing the grow th

o f a s p irit o f p a trio tism and general

confidence. She never m arried, b u t used

its possibility as a d ip lo m a tic to o l. She

became known as ‘ the virgin queen’. The

area w hich later became the state o f

V irginia in the USA was named a fte r her

by one o fth e many English explorers o f

the tim e (Sir W a lte r Raleigh).

-1 r

Q

Q

The Spanish Arm ada.

A fleet o f ships sent by

the C atholic King Philip o f Spain to

help invade England, is defeated by

the English navy (w ith the help o f a

v iolent sto rm !).

JLO O O

1603

James VI o f Scotland

becomesjames I o f

England as well.

'|

g " The G unpow der Plot.

A group o f Catholics

fail in their a tte m p t to blow up the

king in Parliam ent (see chapter 23).

22

HISTORY

T h e seventeenth cen tu ry

W hen James I became the first English king o f the S tuart dynasty,

he was already James VI o f Scotland, so th a t the crowns o f these two

countries were united. A lthough their governments continued to be

separate, their linguistic differences were lessened in this century. The

kind o f Middle English spoken in lowland Scotland had developed

into a w ritten language known as ‘Scots’. However, the Scottish

P rotestant church adopted English rather than Scots bibles. This

and the glam our o f the English court where the king now sat caused

m odern English to become the w ritten standard in Scotland as well.

(Scots gradually became ju st ca dialect’.)

T h e C iv il W a r

T his is rem embered as a contest

between a risto cra tic , royalist

‘ C avaliers’ and p u rita n ic a l

p a rlia m e n ta ria n ‘ R oundheads’

(because o fth e style o f th e ir

hair-cuts). The R oundheads

were v icto rio u s by 1 645,

altho ugh the w a r p e rio d ica lly

con tinu ed u n til 1 649.

In the seventeenth century, the link between religion and politics

became intense. At the start o f the century, some people tried to

kill the king because he w asn’t C atholic enough. By the end o f the

century, an o th er king had been killed, partly because he seemed

too Catholic, and yet an o th er had been forced into exile for the

same reason.

This was the context in which, during the century, Parliam ent

established its supremacy over the monarchy. Anger grew in the

country at the way the S tuart monarchs raised money w ithout, as

tradition prescribed, getting the agreem ent o f the House o f Com m ons

first. In addition, ideological Protestantism , especially Puritanism ,

had grown in England. Puritans regarded the luxurious lifestyle o f

the king and his followers as immoral. They were also anti-Catholic

and suspicious o f the apparent sympathy towards Catholicism o f the

Stuart monarchs.

This conflict led to th e Civil War (The Civil War), w hich ended

w ith com plete victory for the parliam entary forces. Jam es’s son,

Charles I, became the first m onarch in Europe to be executed

after a form al trial for crimes against his people. The leader o f the

parliam entary army, Oliver Cromwell, became ‘Lord P ro tecto r’ o f

a republic w ith a m ilitary governm ent which, after he had brutally

crushed resistance in Ireland, effectively encom passed all o f Britain

and Ireland.

But by the tim e Cromwell died, he, his system o f governm ent, and

the p u ritan ethics th a t went w ith it (theatres and oth er form s o f

am usem ent had been banned) had become so u n p o p u lar th a t the

executed king’s son was asked to retu rn and become King Charles II.

1642

The Civil W ar begins.

1 /a / 1 Q

Charles I is executed.

i U T y

For the firs t and only

tim e, Britain briefly becomes a republic

and is called ‘the C om m onw ealth’.

The Restoration o f

l U O U

the monarchy and the

Anglican religion,

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

However, the conflict between monarch and Parliament soon re-emerged

in the reign o f Charles IPs brother, James II. Again, religion was its

focus. James tried to give full rights to Catholics, and to prom ote them

in his government. The ‘Glorious Revolution’ (‘glorious’ because it was

bloodless) followed, in which Prince William o f Orange, ruler o f the

Netherlands, and his Stuart wife Mary accepted Parliament’s invitation to

become king and queen. Parliament immediately drew up a Bill o f Rights,

which limited some o f the m onarch’s powers. It also allowed Dissenters

(those Protestants who did not agree with the practices o f Anglicanism)

to practise their religion freely. This m eant th a t the Presbyterian Church,

to which the majority o f the lowland Scottish belonged, was guaranteed

its legality. However, Dissenters were not allowed to hold governm ent

posts or become Members o f Parliam ent (MPs).

S t. P a u l’ s C a th e d ra l

23

R in g -a -rin g -a -ro s e s

Ring-a-ring-a-roses,

a pocket fillI o f posies.

Atishoo! Atishoo!

We all fall down.

This is a well-known children’s

nursery rhyme today. It is believed

to come from the tim e o fth e

Great Plague o f 1665, w hich

was the last outbreak o f bubonic

plague in Britain. The ring o f roses

refers to the pattern o f red spots

on a sufferer’s body. The posies,

a bag o f herbs, were th o u g h t to

give protection from the disease.

‘A tishoo’ represents the sound

o f sneezing, one o f the signs o f

the disease, after which a person

could sometimes ‘fall do w n’ dead

in a few hours.

T h e B a ttle o f t h e B o yn e

A fte r he was deposed from the

English and Scottish thrones,

James II fled to Ireland. But the

Catholic Irish army he gathered

there was defeated at the Battle o f

the Boyne in 1690 and laws were

then passed fo rbidding Catholics

to vote o r even own land. In Ulster,

in the north o f the country, large

numbers o f fiercely anti-C atholic

Scottish Presbyterians settled (in

possession o f all the land). The

descendants o f these people are

still known today as Orangemen

(a fte r their patron W illia m o f

Orange). They form one h a lf

o f the tragic s p lit in society in

modern N orthern Ireland, the

oth e r h a lf being the ‘ native’

Irish C atholic (see page 29 The

creation o f N orthern Ireland).

1666

The Great Fire o f

London destroys m ost

o fth e city’s old wooden buildings. It

also destroys bubonic plague, which

never reappears. M ost o fth e city’s

finest churches, including St. Paul’s

Cathedral, date from the period o f

rebuilding which followed.

1688

The Glorious

Revolution.

1690

The Presbyterian

Church becomes the

official ‘Church o fS c o tla n d ’.

24

HISTORY

T h e e ig h te e n th cen tu ry

In 1707, the Act o f Union was passed. Under this agreement, the

Scottish parliam ent was dissolved and some o f its members joined

the English and Welsh parliam ent in London and the form er two

kingdom s became one ‘United Kingdom o f Great B ritain’. However,

Scotland retained its own system o f law, more similar to continental

European systems th an th a t o f England’s. It does so to this day.

Politically, the eighteenth century was stable. M onarch and Parliam ent

got on quite well together. One reason for this was th a t the m onarch’s

favourite politicians, through the royal power o f patronage (the ability

to give people jobs), were able to control the election and voting habits

o f a large num ber o f MPs in the House o f Commons.

T h e o rig in s o f m o d e rn

g o v e rn m e n t

The monarchs o fth e eighteenth

century were Hanoverian

Germans w ith interests on the

European continent. The firs t

o f them , George I, could n o t

even speak English. Perhaps this

situation encouraged the h abit

whereby the m onarch appointed

one principal, o r ‘ p rim e’, m inister

from the ranks o f Parliament

to head his governm ent. It was

also d u ring this century th a t

the system o f an annual budget

draw n up by the m onarch’s

Treasury officials fo r the approval

o f Parliament was established.

1707

1708

The A ct o f Union is passed.

The last occasion on which

a British monarch refuses

to accept a bill passed by Parliament.

W ithin Parliament, the bitter divisions o f the previous century were

echoed in the form ation o f w o vaguely opposed, loose collections o f

allies. One group, the Whigs, were the political ‘descendants’ o f the

parliam entarians. They supported the Protestant values o f hard work

and thrift, were sympathetic to dissenters and believed in governm ent

by monarch and aristocracy together. The other group, the Tories, had a

greater respect for the idea o f the monarchy and the importance o f the

Anglican Church (and sometimes even a little sympathy for Catholics

and the Stuarts). This was the beginning o f the party system in Britain.

The only p art o f Britain to change radically as a result o f political

forces in this century was the highlands o f Scotland. This area twice

supported failed attem pts to p u t a (Catholic) S tuart m onarch back

on the throne. After the second attem pt, many inhabitants o f the

highlands were killed or sent away from Britain and the wearing o f

highland dress (the tartan kilt) was banned. The Celtic way o f life was

effectively destroyed.

It was cultural change th at was m ost marked in this century. Britain

gradually acquired an empire in the Americas, along the west African

coast and in India. The greatly increased trade th at this allowed was one

factor which led to the Industrial Revolution. O ther factors were the

many technical innovations in manufacture and transport.

1746

A t the battle

o f Culloden, a

governm ent army o f English and

low land Scots defeat the highland

arm y o f Charles Edward, w ho, as

grandson o fth e last S tu a rt king,

claimed the British throne. A lthough

he made no a tte m p t to protect his

supporters from revenge attacks

afterw ards, he is still a pop u la r

rom antic legend in the highlands, and

is known as ‘ Bonnie Prince Charlie’.

1-7 S '

The English w riter

-L /

Samuel Johnson coins

the famous phrase, ‘When a man is

tired o f London, he is tired o f life’.

1771

For the firs t tim e,

P arliam ent allow s

w ritte n records o f its debates to be

published freely.

1782

James W a tt invents the

firs t steam engine.

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

In England, the grow th o f the industrial m ode o f production,

together w ith advances in agriculture, caused the greatest upheaval

in the p a tte rn o f everyday life since the Germ anic invasions. Areas o f

com m on land, which had been used by everybody in a village for the

grazing o f animals, disappeared as landow ners incorporated them

into their increasingly large and m ore efficient farms. (There rem ain

some pieces o f com m on land in B ritain today, used m ainly as parks.

They are often called ‘the com m on’.) M illions moved from rural

areas into new towns and cities. M ost o f these were in the n o rth

o f England, where the raw m aterials for industry were available.

In this way, the n o rth , which had previously been economically

backward, became the industrial h eartlan d o f th e country. The right

conditions also existed in low land Scotland and so u th Wales, which

fu rth er accentuated the differences between these parts o f those

countries and their other regions. In the so u th o f England, London

came to dom inate, n o t as an industrial centre, b u t as a business and

trading centre.

25

N e ls o n ’ s C o lu m n

C h a ts w o r th H o u s e : a c o u n tr y s e a t

Despite all the urban

developm ent o fth e eighteenth

century, social pow er and

prestige rested on the

possession o f land in the

countryside. The o utw ard

sign o f this prestige was the

ow nership o f a ‘c o u n try seat’ a gracious c o u n try mansion

w ith land attached. M ore than

a thousand such m ansions

were b u ilt in this century.

't

A fte r a war, Britain

_L / O

loses the southern h a lf

o f its N o rth American colonies (giving

b irth to the USA).

■A Q r v r v

-L C J \ J \ J

1788

1805

The first British settlers

(convicts and soldiers)

arrive in Australia.

The separate Irish

p arliam ent is closed

and the United Kingdom o f Great

Britain and Ireland is form ed.

A B ritish fleet under

the com m and o f

A d m ira l H o ra tio Nelson defeats

N a p o le o n ’s French fle e t at the

Battle o fT ra fa lg a r. N elson’s C olum n

in T ra fa lg a r Square in London

com m em orates this n a tio n a l hero,

w h o died d u rin g the battle.

1829

R obert Peel, a

governm ent minister,

organizes the firs t modern police

force. The police are still sometimes

known today as ‘ bobbies’ ( ‘ Bobby’ is

a s h o rt form o fth e name ‘ R obert’).

Catholics and non-Anglican

Protestants are given the rig h t to hold

governm ent posts and become MPs.

26

HISTORY

T h e n in e te e n th cen tu ry

Q u e e n V ic t o r ia

Queen V icto ria reigned

from 1837-1901. D uring her

reign, although the m odern

powerlessness o fth e monarch

was confirm ed (she was

sometimes forced to accept as

Prime M inister people w hom she

personally disliked), she herself

became an increasingly pop u la r

symbol o f B rita in ’s success in

the w o rld . As a hard-working,

religious m other o fte n children,

devoted to her husband, Prince