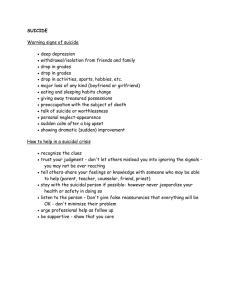

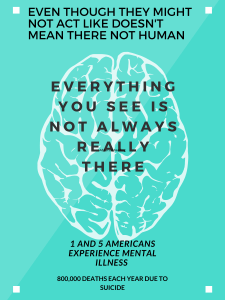

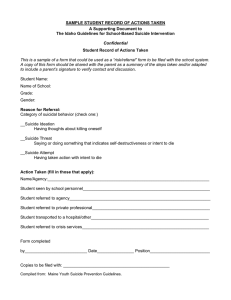

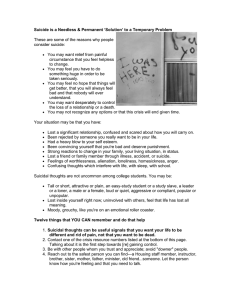

Republic of the Philippines CENTRAL MINDANAO UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF NURSING University Town, Musuan, Maramag, Bukidnon E-mail: nursing@cmu.edu.ph Dignity in Death and Dying A Case Study Presented to the Faculty of the College of Nursing, Central Mindanao University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements in NCM 67: HEALTH CARE ETHICS (BIOETHICS) BSN- 2C GROUP 3 Cutab, ALthea Christine D. Gatpandan, Rik Harold Galvez, Gianna Gail T. Engbino, Paul Carlo B. Densing, Ben M. CLINICAL INSTRUCTOR Reina Geronca Babaran, RN June 2023 Table of Contents Page Preliminaries Table of Contents Introduction 2 3 Rationale 4 Objectives 5 TOPICS Suicide 6 End-of-Life Issues 8 A. Advance Directives 8 B. DNR or End-of-Life Care Plan C. Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide 8 9 D. Dysthanasia E. Orthonasia 10 10 F. Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment G. Withdrawing or Withholding Food and fluids 11 11 Nursing Responsibilities 12 References 19 Introduction The uncertain balance between life and death in the human experience includes significant ethical, intellectual, and emotional issues. The idea of dignity—a fundamental ideal that emphasizes the respect and merit we accord to every person, even in their final moments—lies at the center of this intricate tapestry. The issues of dignity in death and dying is explored in this report manuscript, by exploring the various facets of these topics, we seek to shed light on the underlying factors, psychological aspects, ethical considerations, cultural perspectives, and interventions associated with these crucial areas. People who are suffering from terminal illnesses or intolerable agony frequently find themselves faced with difficult decisions as the end of their journey nears. Even though it is intrinsically upsetting, the topic of suicide demands careful consideration since it involves several nuanced variables, including personal autonomy, mental health issues, social stigma, and the complex web of human emotions. We can shed light on the terrible reality that some people encounter in their search for solace by comprehending the causes and consequences of this act. While inflicting indignity on others is morally wrong and shows a lack of respect for their human dignity, it does not take away their dignity in any minimum or comprehensive sense. A person is harmed and offended if he/she is the victim of involuntary euthanasia or is misled about his/her diagnosis, but he/she can still live his/her life and pass away with (greater or lesser) dignity despite such humiliation. Christ (and other martyrs) endured terrible suffering, but they all passed away with dignity. Mohammed Ali receives appreciation from time to time for the poise with which he handles his Parkinson's condition. Regardless of the circumstances surrounding their passing, people die with dignity because of their character traits and virtues; indignity is endured; dignity is acquired. It follows that a dignified death will be something earned. Someone who lives a good life, lives virtuously, will die in that way (Allmark, 2019). In the notion of dying with dignity described, the terms "death" and "dignity" are used to refer to the act of dying and a person who lives well (in the Aristotelian meaning of doing so in accordance with reason) respectively. This means that having dignity is a personal achievement and that having a dignified death is not something that can be bestowed upon a person by others, such as medical experts. In contrast, indignities are insults to one's self-respect. They are factors that make it difficult or impossible for someone to live honorably, mostly because they make it impossible for him to participate actively and intelligently in his own life. Health care professionals have a twin role here; the first is not to impose such indignities, the second is to minimize them, wherever possible (Allmark, 2019). It is important to recognize that the idea of dying with dignity goes beyond the typical narratives around natural or peaceful deaths when discussing the topic of dignity in death and dying. It is important to understand that people who choose to commit suicide, euthanize themselves, or engage in other intentional methods of dying nonetheless have a fundamental desire to pass away in dignity. There should be no strict limitations on what constitutes an appropriate end-of-life situation or what constitutes dying with dignity. It is a very individualized and subjective idea that is closely connected to a person's ideals, degree of independence, and specific life situations. It is important to recognize that dignity can appear in a variety of ways, especially in the face of purposefully hurried or unusual deaths, whether one chooses physician-assisted suicide to end unbearable suffering or decides to express their autonomy through self-determined death (Westphal et al., 2019). By embracing a broader perspective, we can cultivate a compassionate understanding that respects the complexity of human experiences. We can face the moral quandaries and social taboos related to these decisions by acknowledging and having meaningful debates about purposeful fatalities. By doing this, we can create an atmosphere that respects the dignity of people who commit suicide, choose euthanasia, or engage in other types of intentional death. We can also promote compassion, support, and thorough mental health care to lessen the underlying stress that may influence such decisions. RATIONALE The broad idea of dignity in death and dying is explored in this report manuscript, with a focus on purposeful deaths including suicide, Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) orders, euthanasia, and dysthanasia. It offers a thorough investigation of their impact on personal autonomy, end-of-life care, and social attitudes and tries to provide light on the moral, legal, and emotional conundrums surrounding these practices. This paper aims to provide a deeper awareness of the issues of dignity in the face of mortality and spark meaningful dialogues by addressing the difficulties posed by purposeful deaths. OBJECTIVES General Objectives At the end of this report, the reporters of this group will be able to expand the perspectives of student nurses regarding sensitive topics, with the intention of enhancing their comprehension of the underlying causes behind such incidents occurring within a healthcare environment. Specific Objectives At the end of this report, the reporters of this group will be able to: ● Define dignity in death and dying while also defining all issues related to it such as Suicide, End-of-life Issues: Advance Directives, DNR, or End of Life Care Plan; Euthanasia and assisted suicide, dysthanasia, Orthonasia , termination of life-sustaining-treatment, withdrawing or witholding food and fluids. ● Analyze the ethical issues of dignity in death and dying while also analyzing all issues related to it such as Suicide, End-of-life Issues: Advance Directives, DNR, or End of Life Care Plan; Euthanasia and assisted suicide, dysthanasia, Orthonasia , termination of life-sustaining-treatment, withdrawing or witholding food and fluids. ● Identify the key principles and considerations involved in each of these ethical issues. ● Discuss the different nursing roles and responsibilities of the different issues stated. ● Explain as to how a person can make ethical decisions in such situations. ● Evaluate personal views on the different issues in the beginning of the report and compare how they view things after the report. SUICIDE Suicide is defined as the intentional act of killing oneself. Because the objective is to prevent suicide and provide treatment, it is essential not to use the term “successful suicide” (Soreff & Xiong, 2022). Depression, schizophrenia, alcoholism/substance abuse, and personality disorders (antisocial, borderline, and paranoid) are frequently associated with suicidal ideation. Physical illness (chronic illnesses such as HIV, AIDS, recent surgery, and pain) and environmental factors (unemployment, family history of depression, isolation, and recent loss) may also contribute to suicidal behavior (Nock et al., 2009). Suicidal ideation, also known as suicidal thoughts or ideas, is a broad term that encompasses a variety of contemplations, desires, and preoccupations with death and suicide. Active suicidal ideation refers to the presence of present, distinct suicidal thoughts. It is present when there is a conscious desire to inflict self-harming behaviors, and the client has any desire for death to occur as a consequence. Passive suicidal ideation refers to a general desire to die without a plan to inflict lethal self-harm to commit suicide. This includes indifference to one's own accidental demise if steps are not taken to preserve life (Harmer et al., 2023). Suicide attempt patients frequently have underlying psychiatric disorders, with mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder being the most prevalent. Additionally, schizophrenia and organic brain disorders are associated with an increased risk of suicide, especially when accompanied by auditory hallucinations urging self-harm. Additionally, substance abuse, mental disorders, psychological states, cultural and social circumstances, and genetics all contribute to the risk of suicide (Nock et al., 2009). Globally, an estimated 700,000 people take their own lives annually. Of these global suicides, 77% occur in low- and middle-income countries (Soreff & Xiong, 2022). Men and women tend to commit suicide in different ways. Asphyxiation, hanging, firearms, jumping, and sharp objects are the most common methods used by men, while self-poisoning, exsanguination, drowning, hanging, and firearms are more common among women (Tsirigotis et al., 2011). Nurses play a vital role in suicide prevention and the care of patients at risk. They contribute to interventions at the system level by ensuring environmental safety, enhancing protocols and policies, and taking part in staff training. At the patient level, nurses assess outcomes, evaluate suicide risk, monitor and manage at-risk patients, and administer psychotherapeutic interventions specific to suicide prevention. Developing a therapeutic relationship and taking suicidal threats and attempts seriously are essential components of hands-on nursing care (Martin, P., 2023). The nursing priorities for patients with suicidal ideation are as follows: 1. Establish a Therapeutic Relationship. It is essential to develop a supportive and trustworthy relationship with the patient. To create a safe environment for patients to express their emotions and concerns, the nurse should demonstrate empathy, active listening, and a nonjudgmental attitude. 2. Perform a Comprehensive Assessment. Conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the patient's mental health, including suicidal ideation, intent, and plan. Assess the presence of any underlying psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, or psychosocial stressors that may increase the risk of suicide. 3. Implement Safety Measures. Take immediate action to ensure the safety of the patient. Depending on the healthcare facility's policies, this may involve removing potentially harmful objects or substances from the patient's environment, implementing close observation, or taking suicide precautions. 4. Cooperatively develop a Safety Plan. Collaborate with the patient to create a personalized safety plan that includes methods for coping with suicidal thoughts or urges. This plan may consist of identifying support systems, establishing coping mechanisms, and creating a crisis response plan containing emergency contact information. 5. Offer Education and Assistance. Inform the patient and his or her family about suicide risk factors, warning signs, and resources. If applicable, provide psychoeducation on coping skills, stress management techniques, and the significance of medication adherence. Provide emotional support and encourage the participation of supportive people or community resources. 6. Emotional support and building self-esteem. Promoting self-esteem and resilience entails encouraging the patient to engage in activities that enhance their self-worth and sense of purpose, as well as fostering healthy coping mechanisms to enhance resilience. Enhancing social support involves including the patient's support network and promoting open communication to seek assistance from trusted individuals during times of distress. These interventions aim to enhance the patient's well-being and strengthen their support network. 7. Promoting positive coping mechanisms. Suicidal clients may have ineffective coping mechanisms due to factors such as a disruption in their pattern of tension release, which can result in the impulsive use of extreme solutions. Inadequate coping skills or a lack of social support may also leave them feeling overwhelmed and incapable of managing their emotions in a healthy manner. Inadequate social skills or negative relationship traits may also contribute to feelings of isolation and the inability to seek assistance from others. 8. Managing hopelessness. Due to their overwhelming and persistent challenges, clients with suicidal behaviors related to abandonment, chronic pain, deteriorating physiological condition, loss of significant support system, prolonged isolation, severe stressful events, and chronic pain may experience feelings of hopelessness. These factors can result in a sense of despair and a belief that the situation is hopeless, making individuals more susceptible to suicidal thoughts and actions. End-of-Life Issues: Advance Directives Advance care planning is the process by which a mentally capable person documents their healthcare wishes if they were to lose the ability to decide for themselves. This is increasingly done today with what is called an advance directive (Cantor, 1993; President’s Commission, 1983). In essence, an advance directive is a documented expression of the patient’s wishes. An advance directive has two parts: ● living will (or substantive directive) ● healthcare power of attorney (or proxy directive). A mentally capable person can fill out either of these parts of an advance directive. One can also combine these two forms of directives into a single document that serves both to specify the general types of treatment one would want and names someone to interpret one’s wishes in cases of ambiguity. A living will, or substantive directive ● records the patient’s substantive wishes about medical treatment. Usually, but not always, it is designed to apply when the patient is terminally ill or in a permanent vegetative state (a brain disorder where there is no sign of awareness, and there is no expectation of recovery). Patients can write out certain things they would not like. Ventilators, chemotherapy, medically supplied nutrition and hydration, and other means of aggressive life-sustaining treatments are often mentioned. They can also record certain treatments that they would want to have provided. These may include palliative care, but could also include medically supplied nutrition. If a patient has unusual desires to receive life-sustaining technologies, it is important that those wishes be recorded because, increasingly, the norm is not to provide them for terminally ill and permanently unconscious patients. A healthcare power of attorney, or proxy directive, ● specifies the person to serve as a surrogate decision-maker in the event the patient is unable to speak for himself or herself. An advance directive naming a proxy is particularly crucial for those who do not want their legal next of kin to be their agent. Because legally the spouse is the next of kin, feuding spouses may want some other relative or friend to function as decision-maker. A person with an incapacitated spouse or one for whom taking an active role as decision-maker would be too much of a burden may wish to name someone else; a brother or sister, an adult son or daughter, a friend, or someone else may be so named DNR or End-of-Life Care Plan End of life care includes Palliative care. If you have an illness that can’t be cured, based on the understanding that death is inevitable. Palliative care makes you as comfortable as possible, by managing your pain and other distressing symptoms. It also involves psychological, social, and spiritual support for you and your family or career. When does end-of-life care begin? ● Have an advanced incurable illness, such as cancer, dementia, or motor neuron disease, are generally frail and have co-existing conditions that mean they are expected to die within 12 months. ● Have existing conditions if they are at risk of dying from a sudden crisis in their condition ● Have a life-threatening event, such as an accident or stroke Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide Assisted suicide, also known as physician-assisted suicide or medical aid in dying, is a procedure where a person who is terminally ill and experiencing excruciating pain or other irreversible physical conditions asks for help from a medical practitioner to terminate their life. It entails a voluntarily made decision by the person, with the help of a healthcare professional, to acquire the tools to hasten their own demise. Euthanasia on the other hand is not a happy incident; it is the act of killing a life and is known as mercy killing or providing peaceful death. Patients who are chronically or terminally ill and have run out of options for treatment receive it. Patients who are unable to deal with the clinical manifestation of such disorders, which result in terrible pain and suffering, will ask to terminate their life. Euthanasia is carried out willingly and with the patient's consent. This is the term used in bioethics to describe doctors administering a deadly injection to hasten a patient's death. Euthanasia The word ‘euthanasia’ comes from the Greek word ‘eu’ meaning good or well and ‘thanatos’ meaning death; hence, euthanasia means good death. The term explains that it is an intentional termination of life by another at the explicit request of the person who wishes to die. ● ● Voluntary: When euthanasia is conducted with consent. Voluntary euthanasia is currently legal in Belgium, Luxemburg, The Netherlands, Switzerland, and the States of Oregon and Washington in the U.S Non-voluntary: euthanasia is when euthanasia is conducted on a person who is unable to consent due to their current health condition. In this scenario, the decision is made by another appropriate person, on behalf of the patient, based on their quality of life and suffering. ● Involuntary: When euthanasia is performed on a person who would be able to provide informed consent, but does not, either because they do not want to die, or because they were not asked. This is called murder, as it’s often against the patient’s will. Dysthanasia Dysthanasia is in the aim to prolong the lives of terminal patients, this treatment causes them great misery. This method only prolongs the dying process rather than extending life. The development of knowledge and its application frequently jeopardize the dignity and quality of life of those who suffer. Dysthanasia can be stopped effectively with palliative care and respect for patients' rights. It Is a term generally used when a person is seen to be kept alive artificially in a condition where, otherwise, they cannot survive; sometimes for some sort of ulterior (intentionally hidden/future) motive. "Dysthanasia" is a term used to describe a situation where a patient is subjected to excessive or prolonged medical interventions in an attempt to prolong their life, despite there being little or no chance of a meaningful recovery or improvement in their condition. It is often referred to as "bad death" or "futile care." In dysthanasia, medical interventions are continued or even intensified without considering the patient's overall well-being, quality of life, or their expressed wishes. This may result in unnecessary suffering, discomfort, and a diminished quality of life for the patient. The concept of dysthanasia highlights the ethical dilemma of providing medical interventions that offer little benefit or may even harm the patient, leading to a prolonged and potentially agonizing dying process. It stands in contrast to the concept of "euthanasia" or "good death," which involves the deliberate and compassionate act of ending a patient's life to relieve their suffering in certain circumstances. Dysthanasia is often discussed in the context of end-of-life care and medical ethics, emphasizing the importance of respecting a patient's autonomy and their right to make decisions about their own healthcare, including the option to refuse futile or burdensome treatments. Orthonasia A normal or natural manner of death and dying. Sometimes used to denote the deliberate stopping of artificial or heroic means of maintaining life Orthonasia" is a term that is not widely recognized or used within medical or bioethical literature. It is possible that you may be referring to "orthothanasia" or "a good death," which is an approach that focuses on providing compassionate care and ensuring a comfortable and dignified death for terminally ill patients. Orthothanasia emphasizes the importance of appropriate pain management, symptom relief, and psychological and emotional support for individuals nearing the end of life. The goal is to allow the natural process of dying to take place without unnecessary medical interventions that may prolong suffering or provide little benefit. In contrast to euthanasia or assisted suicide, which involve actively causing the death of a patient, Orthonasia does not involve intentionally hastening death. It aims to respect the autonomy and wishes of the patient while prioritizing their comfort and quality of life. Orthothanasia is often advocated within the framework of palliative care, which is a multidisciplinary approach that focuses on relieving suffering and improving the quality of life for patients with serious illnesses, including those nearing the end of life. Palliative care teams work collaboratively with patients, their families, and healthcare providers to address physical, emotional, and spiritual needs. It is important to note that terminology and approaches related to end-of-life care can vary across different countries and cultures. The specific practices and legal frameworks related to end-of-life decisions may also differ, so it is crucial to consult local laws and ethical guidelines for a comprehensive understanding of the topic. Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment is the process of terminating medical treatments or interventions meant to extend a person's life when there is no chance of recovery and the treatment is just prolonging the process of death. Clinically, "termination of life support" is important. It is beneficial for end-of-life patients whose wishes have been communicated to refrain from any harsh procedures in the event that their clinical condition worsens. It prevents care that is pointless, may include invasive measures, and may have a negative influence on the patient's quality of life without providing a material improvement in survival. The comfort of seeing a pain-free and peaceful death of a loved one also goes to the bereaved family. To make sure that the choice is made in the patient's best interest and in line with their intentions, healthcare providers frequently adhere to established standards and regulatory criteria. This may entail having conversations with the patient, their family, and the medical staff while taking into account things like the patient's prognosis, quality of life, and any wishes that have already been communicated, such as through advance directives or living wills. Medical measures, such as mechanical ventilation, artificial nourishment, and hydration, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), may be gradually reduced or stopped once the decision to stop life-sustaining care has been taken. With no need for procedures that would merely prolong pain without providing a hope for recovery, this enables the patient to die naturally. Withdrawing or Withholding Food and fluids Withdrawing or withholding food and liquids, commonly referred to as "voluntary stopping of eating and drinking" (VSED), refers to the conscious choice to stop giving nourishment and hydration to a person who is physically able to eat and drink but has chosen to refuse it. This choice is frequently made by people who are terminally sick, going through severe agony, and want to pass away sooner. The elimination of nourishment in VSED is typically regarded as a sort of passive euthanasia, when medical therapies or treatments are not actively delivered to end a person's life but rather allow the underlying sickness or condition to continue naturally. Nursing Roles and Responsibilities SUICIDE 1. Risk assessment and establishing therapeutic relationship Clients with a history of alcohol and substance abuse, as well as those who have experienced abuse, are at increased risk for suicide due to the negative impact of these factors on their mental well-being. Additionally, individuals with a family history of suicide, a history of psychiatric illness, or a prior suicide attempt are also at higher risk due to genetic and environmental influences, as well as ongoing mental health challenges. 2. Perform screening for suicidal ideations. A variety of suicidal ideation screening and suicide risk assessment scales have been validated and meet the Joint Commission’s requirement for primary care, emergency department, and behavioral health professionals to assess individuals with behavioral health issues. Tools should be consistent with the client’s age, the setting, and organizational policies. Examples of screening tools in the emergency department include the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), Manchester Self-Harm Rule, and Risk of Suicide Questionnaire (Harmer et al., 2023). 3. Assess for early signs of distress or anxiety and investigate possible causes. Anxiety in all its forms leads to a risk of suicide; the constant sense of dread and tension proves unbearable for some. In addition to suicide inquiry, the potential for homicide inquiry must be assessed. Aggression turned inward is suicide; aggression turned outward is homicide. There is a linkage between homicide and suicide in adolescents, wherein two of the leading causes of violent death are suicide and homicide (Soreff & Xiong, 2022). 4. Monitor for suicidal or homicidal ideation. These are indicators of the need for further assessment and intervention or psychiatric care. Determine whether the client has any thoughts of hurting themself. Suicidal ideation is highly linked to completed suicide. Because suicide constitutes an aggressive act, the question regarding homicidal tendencies must be asked (Soreff & Xiong, 2022). 5. Assess suicidal intent on a scale of 0 to 10 or by asking directly if the client is thinking of killing themself, or has plans, means, and so on. This provides guidelines for the necessity and urgency of interventions. Direct questioning is most helpful when done in a caring and concerned manner. Of the 9.4 million clients with serious thoughts of suicide, 2.7 million reported they had made suicide plans, and 1.1 million made a nonfatal suicide attempt (Soreff & Xiong, 2022). 6. Maintain straightforward communication and assist the client to learn assertive rather than manipulative or aggressive behavior. This avoids reinforcing manipulative behavior and enhances positive interactions with others, accomplishing the goal of getting needs met in acceptable ways. The nurse must be clear and consistent with boundaries, expectations, and limitations. The client must understand that the staff is there to support them but that they will not tolerate manipulation, threats, or abusive behavior. 7. Help the client choose activities to redirect their emotions. This promotes the release of energies in acceptable ways. Redirecting a confused client can minimize the escalation of agitation. Using an effective coping strategy such as a task-focused coping style helps the client to think less about suicide. This coping style helps the client by managing their emotions and engendering a commitment to useful social activities (Addollahi & Carlbring, 2017). 8. Acknowledge the reality of suicide or homicide as an option. Discuss the consequences of actions if the client were to follow through on their intent. The client may focus on suicide, or possibly homicide, as the “only” option, and this response provides an opening to look at and discuss other options. For any decision, most people naturally weigh the costs and benefits of the potential action. The nurse’s task is to help the client recognize and weigh the negative aspects to tip the scale in favor of change (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). 9. Remain calm and state limits on behavior in a firm manner. Understanding that helplessness and fear underlie this behavior aids in choosing the appropriate response. Avoid giving in to the client’s demands, threats, or manipulation. Help the client recognize the consequences of their actions and choices, and hold them accountable for their behavior. POSSIBLE QUESTIONS TO ASK A CLIENT ● ● ● “Have you ever considered harming yourself?” Suicide ideation is the manner of thinking about killing oneself. The patient’s risk for suicide progresses as these thoughts become more frequent. “Have you ever attempted suicide?” The patient’s status of suicide risk is distinguished if there is a history of earlier suicide attempts. “Do you currently consider like killing yourself?” This allows the person to discuss feelings and issues openly. ● ● “What are your plans with regard to killing yourself?” Citing a plan and the ability to carry it out greatly increases the risk for suicide. The more harmful the plan, the more serious the risk for suicide. “Do you trust yourself to maintain control over your insights, emotions, and motives?” Patients with suicidal thoughts may sense their authority of suicidal thoughts slipping away, or they may feel themselves surrendering to a desire to end their life. END OF LIFE CARE (Euthanasia, Dysthanasia, Othonasia, Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment, Withdrawing or Withholding Food and fluids) A. Promoting Effective Coping Abilities 1. Promoting Effective Coping Abilities Family coping for patients in hospice care involves a range of emotional, psychological, and practical responses. Families may experience anticipatory grief, stress, and a need for support as they navigate the impending loss of their loved one. They may engage in various coping strategies, such as seeking emotional support from healthcare providers, connecting with support groups, or utilizing spiritual or cultural resources to find comfort and meaning during this challenging time. 2. Assess the level of anxiety present in the family and/or SO. Anxiety level needs to be dealt with before problem-solving can begin. Individuals may be so preoccupied with the client’s own reactions to situations that they are unable to respond to another’s needs. 3. Determine the level of impairment of perceptual, cognitive, and/or physical abilities. Evaluate illness and current behaviors that are interfering with the care of the patient. Information about family problems will be helpful in determining options and developing an appropriate plan of care. 4. Note the patient’s emotional and behavioral responses resulting from increasing weakness and dependency Approaching death is most stressful when patient and/or family coping responses are strained, resulting in increased frustration, guilt, and anguish. 5. Determine current knowledge and/or perception of the situation. Provides information on which to begin planning care and make informed decisions. 6. Assess the current actions of SO and how they are received by the patient. Lack of information or unrealistic perceptions can interfere with the caregiver’s and/or care receiver’s response to the illness situation. 7. Establish rapport and acknowledge the difficulty of the situation for the family. May assist SO to accept what is happening and be willing to share problems with staff. 8. Discuss underlying reasons for patient behaviors with family. When family members know why the patient is behaving differently, it may help them understand and accept or deal with unusual behaviors. 9. Assist family and patient to understand “who owns the problem” and who is responsible for resolution. Avoid placing blame or guilt. When these boundaries are defined, each individual can begin to take care of own self and stop taking care of others in inappropriate ways. 10. Involve SO in information giving, problem-solving, and care of patients as feasible. Instruct in medication administration techniques, and needed treatments, and ascertain adeptness with the required equipment. Significant others (SO) may be trying to be helpful, but actions are not perceived as being helpful by the patient. In addition, may be withdrawn or can be too protective. B. Decreasing Tolerance to Activity 1. Assess sleep patterns and note changes in thought processes and behaviors. Multiple factors can aggravate fatigue, including sleep deprivation, emotional distress, side effects of medication, and the progression of the disease process. 2. Document cardiopulmonary response to activity (weakness, fatigue, dyspnea, arrhythmias, and diaphoresis). Can provide guidelines for participation in activities. 3. Monitor breath sounds. Note feelings of panic or air hunger. Hypoxemia increases the sense of fatigue and impairs the ability to function. 4. Recommend scheduling activities for periods when the patient has the most energy. Adjust activities as necessary, reducing intensity level and/or discontinuing activities as indicated. Prevents overexertion, and allows for some activity within the patient’s ability. 5. Encourage the patient to do whatever is possible: self-care, sitting in a chair, and visiting with family or friends. Provides a sense of control and a feeling of accomplishment. 6. Instruct patient, family, and/or caregiver in energy conservation techniques. Stress the necessity of allowing for frequent rest periods following activities. Enhances performance while conserving limited energy, preventing an increase in the level of fatigue. 7. Demonstrate the proper performance of ADLs, ambulation, or position changes. Identify safety issues: use of assistive devices, the temperature of bath water, keeping travel ways clear of furniture. Protects patient or caregiver from injury during activities. 8. Encourage nutritional intake and use of supplements as appropriate. Necessary to meet energy needs for activity. 9. Encourage nutritional intake and use of supplements as appropriate. Necessary to meet energy needs for activity. C. Providing Emotional Support and Assisting in Grieving 1. Assess the patient and/or SO for the stage of grief currently being experienced. Explain the process as appropriate. Knowledge about the grieving process reinforces the normality of feelings and/or reactions being experienced and can help patients deal more effectively with them. 2. Monitor for signs of debilitating depression, statements of hopelessness, and desire to “end it now.” Ask the patient direct questions about the state of mind. The patient may feel vulnerable when recently diagnosed with an end-stage disease process and/or when discharged from the hospital. Fear of loss of control and/or concerns about managing pain effectively may cause the patient to consider suicide. 3. Investigate evidence of conflict; expressions of anger; and statements of despair, guilt, hopelessness, and inability to grieve. Interpersonal conflicts and/or angry behavior may be the patient’s or SO’s way of expressing or dealing with feelings of despair and/or spiritual distress, necessitating further evaluation and support. 4. Determine the way that the patient and/or SO understand and respond to death. Determine cultural expectations, learned behaviors, experience with death (close family members and/or friends), beliefs about life after death, and faith in Higher Power (God). These factors affect how each individual faces death and influences how they may respond and interact. 5. Provide an open, nonjudgmental environment. Use therapeutic communication skills of active listening, affirmation, and so on. Promotes and encourages realistic dialogue about feelings and concerns. 6. Encourage verbalization of thoughts and/or concerns and accept expressions of sadness, anger, and rejection. Acknowledge the normality of these feelings. Patients may feel supported in the expression of feelings by the understanding that deep and often conflicting emotions are normal and experienced by others in this difficult situation. 7. Facilitate the development of a trusting relationship with the patient and/or family. Trust is necessary before the patient and/or family can feel free to open personal lines of communication with the hospice team and address sensitive issues. 8. Be aware of mood swings, hostility, and other acting-out behavior. Set limits on inappropriate behavior, and redirect negative thinking. Indicators of ineffective coping and need for additional interventions. Preventing destructive actions enables patients to maintain control and a sense of self-esteem. 9. Reinforce teaching regarding disease processes and treatments and provide information as requested or appropriate about dying. Be honest; do not give false hope while providing emotional support. Patient and/or SO benefit from factual information. Individuals may ask direct questions about death, and honest answers promote trust and provide reassurance that correct information will be given. 10. Review past life experiences, role changes, sexuality concerns, and coping skills. Promote an environment conducive to talking about things that interest the patient. Opportunity to identify skills that may help individuals cope with the grief of current situation more effectively. Issues of sexuality remain important at this stage: feelings of masculinity or femininity, giving up a role within the family, and the ability to maintain sexual activity (if desired). D. Managing Pain 1. Perform a comprehensive pain evaluation, including location, characteristics, onset, duration, frequency, quality, severity (e.g., 0–10 scale), and precipitating or aggravating factors. Note cultural issues impacting reporting and expression of pain. Determine the patient’s acceptable level of pain. Provides baseline information from which a realistic plan can be developed, keeping in mind that verbal/behavioral cues may have a little direct relationship to the degree of pain perceived. Often the patient does not feel the need to be completely pain-free but is able to be more functional when pain is at a lower level on the pain scale. 2. Assess the patient’s perception of pain, along with behavioral and psychological responses. Determine the patient’s attitude toward and/or use of pain medications and locus of control (internal and/or external). Helps identify patients’ needs and pain control methods found to be helpful or not helpful in the past. Individuals with an external locus of control may take little or no responsibility for pain management. 3. Assess the degree of personal adjustment to diagnosis, such as anger, irritability, withdrawal, and acceptance. These factors are variable and often affect the perception of pain and the ability to cope and the need for pain management. 4. Identify specific signs and symptoms and changes in pain requiring notification of healthcare provider and medical intervention. Unrelieved pain may be associated with the progression of a terminal disease process, or be associated with complications that require medical management. 5. Verify current and past analgesic and narcotic drug use (including alcohol). May provide insight into what has or has not worked in the past or may impact the therapy plan. 6. Monitor for/discuss the possibility of changes in mental status, agitation, confusion, and restlessness. Although causes of deterioration are numerous in terminal stages, early recognition and management of the psychological component is an integral part of pain management. 7. Monitor for/discuss the possibility of changes in mental status, agitation, confusion, and restlessness. Although causes of deterioration are numerous in terminal stages, early recognition and management of the psychological component is an integral part of pain management. 8. Discuss with SO(s) ways in which they can assist patients and reduce precipitating factors. Promotes involvement in care and belief that there are things they can do to help. 9. Involve caregivers in identifying effective comfort measures for patients: use of non-acidic fluids, oral swabs, lip salve, skin and/or perineal care, and enema. Instruct in the use of oxygen and/or suction equipment as appropriate. Managing troubling symptoms such as nausea, dry mouth, dyspnea, and constipation can reduce patients’ suffering and family anxiety, improving quality of life and allowing the patient/family to focus on other issues. 10. Demonstrate and encourage the use of relaxation techniques, guided imagery, and meditation. May reduce the need for/can supplement analgesic therapy, especially during periods when the patient desires to minimize the sedative effects of medication. REFERENCES: Allmark, P. (2019). Death with dignity. Journal of Medical Ethics, 28(4), 255–257. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.28.4.255 Bsn, M. V., RN. (2023). 4 End-of-Life Care (Hospice Care) Nursing Care Plans. Nurseslabs. https://nurseslabs.com/end-of-life-care-hospice-care-nursing-care-plans/ Bsn, P. M., RN. (2023). 6 Suicidal Ideation (Hopelessness & Impaired Coping) Nursing Care Plans. Nurseslabs. https://nurseslabs.com/suicide-behaviors-nursing-care-plans/ Dabi, A., & Rahman, O. (2023). Termination of Life Support. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564312/#:~:text= Menezes, M. B. de, Selli, L., & Alves, J. de S. (2009). Dysthanasia: nursing professionals’ perception. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 17(4), 443–448. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-11692009000400002 Martin, P. (2023, April 30). 3 Suicide Behaviors Nursing Care Plans. Nurseslabs. https://nurseslabs.com/suicide-behaviors-nursing-care-plans/ Nock, M. K., Hwang, I., Sampson, N., Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Beautrais, A., ... & Williams, D. R. (2009). Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS medicine, 6(8), e1000123. Soreff, S., & Xiong, G. (2022, June 29). Suicide: Practice Essentials, Overview, Etiology. Medscape.com. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2013085-overview Tsirigotis, K., Gruszczynski, W., & Tsirigotis-Woloszczak, M. (2011). Gender differentiation in methods of suicide attempts. Medical Science Monitor, 17(8), PH65–PH70. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.881887 Veatch, R. M., & Guidry-Grimes, L. K. (2019). The Basics of Bioethics. Routledge. Clement, N. Nursing Ethics Concepts, Trends and Practices (Z-Library).pdf. (n.d.). Westphal, E. R., Nowak, W. S., & Krenchinski, C. V. (2019). Of Philosophy, Ethics and Moral about Euthanasia: The Discomfort between Modernity and Postmodernity. Clinical Medical Reviews and Case Reports, 6(6). https://doi.org/10.23937/2378-3656/1410270