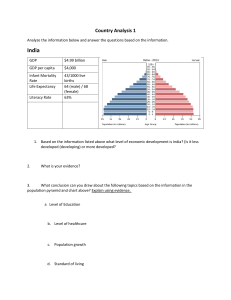

The Impact of Agriculture and Remittance Earnings on Economic Growth in Nepal Rehann Silvanus August 17, 2023 Introduction As a landlocked country, Nepal faces unique challenges to its economy that leave the country dependent on the support of its neighboring countries: China and India. While also among one of the poorest countries in the world, Nepal is ranked 143rd on the Human Development Index.1 Combining this with a low economic and social development rate means that Nepal is placed in a position where it suffers from a low literacy rate, agricultural dependency, and a strong presence of remittance earnings.2 Transitioning from a monarchy to democracy in 2008, economic growth in Nepal has seen periods of stagnant yet rising growth.3 Some of the key determinants behind this growth are worker remittance inflows and the dominating presence of the agricultural industry. Thus, this research topic focuses on examining to which extent remittances and agricultural output have helped foster economic growth in Nepal from 1995 to 2021. When referring to eco1. Prabhat Jha and Shiva Chandra Dhakal, “Factors of Production Influencing Gross Domestic Product in Nepal,” Nepal Journal of Science and Technology 19 (October 2021): 41–45, https://doi.org/10.3126/njst. v20i1.39389. 2. Krishna Prasad Ojha, “Remittance Status and Contribution to GDP of Nepal,” NCC Journal 4 (July 2019): 102–112, https://doi.org/10.3126/nccj.v4i1.24743. 3. Prasiddha Shakya and George Gonpu, “Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth in Nepal,” Nepal Public Policy Review 1 (October 2021): 32–44, https://doi.org/10.3126/nppr.v1i1.43419. 1 nomic growth, the dependent variable of concern in this analysis will be the real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate. Literature Review Copious articles have been written to ascertain what determinants impact the economic growth of a country. Regarding Nepal, factors such as FDI, Gross Fixed Capital Formation, and Remittance earnings have been analyzed extensively to determine the contribution to overall growth.4 Ghimire, Shah, and Phuyal believe that economic growth in Nepal has been stagnant due to weak implementation of international trade policies: leading Nepal to suffer lower growth and unsustainable development.5 The authors concede that the primary influences of economic growth cannot be precisely known; however, they stress the need for a country-specific development plan. Another critical component of Nepal’s Economic Growth in the last two decades has been the money sent back as worker remittance inflows. Shakya and Gonpu note that in 2016, remittances accounted for 31 percent of Nepali GDP in that fiscal year.6 However, after 2016, World Bank Data suggests that remittances as a portion of GDP have experienced a steady decline. The study by Shakya and Gonpu concluded that remittances do not significantly impact real GDP Growth. Moreover, the study found evidence that remittance earnings may negatively impact economic growth in the long run.7 Empirically speaking, this could be due to remittance earnings not being a stable source of income. Fluctuations in earnings due to particular events, such as the pandemic, may cause wages to decline. Thus, proportionally decreasing Nepali GDP. Nepal has been known to be an economy that relies heavily on its agricultural sec4. Luna Ghimire, Ajay Shah, and Ram Phuyal, “Economic Growth in Nepal: Macroeconomic Determinants, Trends and Cross-Country Evidences,” Journal of World Economic Research 9 (May 2020), https://doi. org/10.11648/j.jwer.20200901.20. 5. Ghimire, Shah, and Phuyal. 6. Shakya and Gonpu, “Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth in Nepal.” 7. Shakya and Gonpu. 2 tor for productivity. 2010 World Bank data suggests that 33.2 percent of GDP was contributed from Agriculture, forestry, and fishing (cite Data). Jha and Dhakal note in their research that agricultural land experienced an average growth rate of 0.77 percent from 2001 - 2018. Their regression analysis also concluded that agricultural land did have a statistically significant impact on Nepali GDP.8 Agricultural reliance can be seen as a cornerstone for Nepali economic growth as several uncultivated parts of Nepal still possess arable land.9 Furthermore, Jha and Dhakal implore the Nepalese government to incentivize the agricultural sector by fast-tracking high-value crops. Specification Economic Growth and sustainable development models rely on many indicators that constantly fluctuate due to policies implemented globally. In this analysis, real GDP growth will be the dependent variable as it is an appropriate indicator for the health of an economy. The time frame for the data in this model spans 26 years (1995-2021). Four models will be considered for robustness in this analysis. The models are (1) Key Independent Variables, (2) Unlagged Control Variables, (3) Distributed Lag Model, and (4) Dynamic Model. The time series regression for each of the models will take the following forms: Theoretical Representations Model 1: GDPGrowtht = β0 + β1 AgriculturalOutputt + β2 Remittancest + ϵt Model 2: GDPGrowtht = β0 +β1 AgriculturalOutputt +β2 Remittancest +β3 Inf lationRatet +β4 FDIt + ϵt 8. Jha and Dhakal, “Factors of Production Influencing Gross Domestic Product in Nepal.” 9. Jha and Dhakal. 3 Model 3: GDPGrowtht = β0 +β1 AgriculturalOutputt +β2 Remittancest +β3 Inf lationRatet +β4 FDIt + β5 Inf lationRatet−1 + β6 Remittancest−1 + ϵt Model 4: GDPGrowtht = β0 +β1 AgriculturalOutputt +β2 Remittancest +β3 Inf lationRatet +β4 FDIt + β5 Inf lationRatet−1 + β6 Remittancest−1 + β7 GDPGrowtht−1 + ϵt Where, GDP Growth = percent change in Real GDP (1995-2021), annual Agricultural Output = Value Added by Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing as a percent of GDP (1995 -2021), annual Remittances = percent change in Remittance Inflows (1995-2021), annual FDI = Foreign Direct Investment net inflows as a percent of GDP (1995-2021), annual Inflation Rate = Annual Inflation Rate (1995-2021) Inflation Ratet−1 = Lagged annual Inflation Rate Remittancest−1 = Lagged percent change in Remittance Inflows GDP Growtht−1 = Lagged percent change in Real GDP Data Description & Sources Before discussing the regression estimates, it is vital to consider data trends within the dependent, and independent variables. Data in this analysis has been sourced directly from the World Bank and FRED websites and reproduced for further examination. When we consider real GDP over time for Nepal, Figure 1 indicates that Nepal has experienced steady growth over the past 26 years, with a minor dip in 2020 due to the Covid Pandemic. Figure 2 shows the percentage change in real GDP annually. The only point where negative real GDP growth is exhibited is in 2020 at −2.3%. Another steep decline in real GDP growth was exhibited around 2015. The dip is possibly owing to 4 the 7.8 magnitude earthquake that shook Nepal on April 25th, 2015.10 In the long run, economic growth has tended to recover as expected. Figure 3 shows the trends for the key independent variables from 1995 - 2021. Over time, agricultural output as a percentage of GDP has experienced a steady decline. From composing nearly 40% of Nepali GDP in 1995 to around 21.3% in 2021. Remittance earnings have experienced a polar opposite growth when compared to agricultural output. As a percentage of GDP, remittances have experienced drastic increases in the past 26 years. Composing merely 1% of Nepali GDP in 1995 to around 24% of GDP in 2020. However, in recent years the data suggest a tapering off in contributions from remittances. Table 1 shows a summary statistics table for the variables used in this analysis. When glancing at the observations, it is evident that the number of observations is low. This is due to the nature of the time series data, as the values recorded are based on annual figures. This may pose issues when running regression estimates as it will lessen the chance of identifying statistically significant variables. A solution could be finding data from 1995 - 2021 based on quarterly figures. This could increase our potential observations fourfold up to 104. When looking at the minimum and maximum values of the data, a healthy variance in the range is observed as the values are not too far apart. This aids in eliminating any presence of heteroskedasticity in the data set. As indicated in Table 1 and the model specifications, the following variables will be used to estimate the regressions: [GDP Growth, Agricultural Output, and Remittances have been omitted from the following subsection as they have been extensively discussed] 10. Shakya and Gonpu, “Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth in Nepal.” 5 Variable Description Inflation Rate Data regarding the Nepalese inflation rate have been directly sourced from the World Bank open database. Inflation Rate figures are calculated using the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index on an annual basis. As a key macroeconomic indicator for the health of an economy, the inflation rate is a key determinant for economic growth in a country. Maintaining a stable inflation rate is a crucial function of a country’s central bank, as fears of rising inflation can impact consumer confidence in the economy. Thus, leading to stagnant or unstable economic growth in the short to medium run. FDI Foreign Direct Investment data has been sourced directly from the World Bank open database. Investments of this nature are crucial for the growth of a country’s private sector. FDI supports the accumulation of capital stock for entities operating in an economy. Private sector is the engine of growth since it generates employment while producing goods and services crucial for sustained economic growth. Lagged Inflation Rate Statistical theory suggests that the inclusion of a lagged variable should depend on whether data regarding the previous period/year impacts the outcomes for the following period/year. The inflation rate is a good candidate for use as a lag variable, as macroeconomic theory suggests that the ‘expected’ inflation rate is highly dependent on the inflation rate of the previous period/year. Including this variable in Model 3 results in a distributed lag model. 6 Lagged Remittances Similarly to the lagged inflation rate, a lagged remittances variable was added to the distributed lag model as it was a good candidate for a lag variable. Figure 3 shows how remittances as a percentage of GDP follow a steady increase over time with minor fluctuations. Omitted Variable Basis The existence of omitted variable bias in a regression equation is the unavoidable event that occurs due to omitting a key component/s in the analysis. Omitted variable bias occurs when an independent variable is dropped from a regression equation, resulting in the beta coefficients to be an upper or lower bound estimate of the true value of the beta coefficient. One example of an omitted variable in this analysis is the export of goods and services as a percentage of GDP. The export of goods and services is a crucial component of GDP as it is used in the calculation of net exports. Therefore, it can be selected as a potential independent variable in the regression analysis. By omitting this key variable we have exposed our beta coefficients to omitted variable bias. To determine the direction of bias, it is imperative to determine how the export of goods and services impacts real GDP growth, as well as, how an independent variable impacts the export of goods and services. For instance, consider the impact of omitting the export of goods and service variable in regard to the agricultural output variable. This implies that the estimated value of the β1 coefficient is not equal to the true value of the β1 coefficient. Rather, the estimated value of β1 is E(β1 ) = β1 + β8 αˆ1 . The bias in this situation is β8 αˆ1 . The export of goods and services is a component of determining the trade deficit within a country. When exports exceed imports, trade deficits are positive. Therefore, we can infer that exports have a positive relationship with real GDP. In order to determine the sign for αˆ1 , an auxiliary 7 equation must be created to determine the impact of agricultural output on the exports of goods and services. ˆ Exports t = αˆ0 + αˆ1 AgriculturalOutputt According to OEC, one of Nepal’s main exports are soybean and palm oil.11 These are goods that must be extracted from raw materials grown in Nepal. Thus, an increase in agricultural output is bound to have a positive impact on the export of goods and services. As both the β8 and αˆ1 are positive, one can infer that the estimated value of β1 is an upper bound estimate of the true value of β1 . Regression Results & Findings Using four OLS time series models of regression, the results indicate that remittances are the only statistically significant independent variable across all models. When referring to Table 2, the beta coefficient for remittances in model 1 is −1.264. Meaning that a one unit increase in remittances causes a −1.264 unit change in real GDP growth, holding other variables constant. Across all four models of specification, remittances is statistically significant at the 0.1% level. Moving up from model 1 to model 4, the beta coefficient for remittances becomes more negative. On the other hand, agricultural output does not appear to be statistically significant across any of the models. Although the beta coefficients for agricultural output are positive across all four models, the magnitude of their impact on real GDP growth is negligible. The results found in this analysis contrast the findings found by Shakya and Gonpu. In their regression analysis, the authors found that there was no statistically significant relationship between remittance earnings and economic growth. Moreover, their regres11. “Indian Economy Continues to Show Resilience Amid Global Uncertainties,” The World Bank, 2023, accessed November 29, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/04/04/indianeconomy-continues-to-show-resilience-amid-global-uncertainties. 8 sion estimates from the beta coefficient of remittances was positive. The analysis in this paper concludes that there is a negative relationship between remittances and economic growth across all models of sensitivity. One potential reason for this can be seen by analysing Nepal’s dependency on its import goods. Figure 4 shows Nepal’s imports as a percentage of GDP from 1995 to 2021. The graph shows a non constant increase in the import of foreign goods and services. Imports composed nearly 41% of Nepali GDP in 2019. While not empirically proven, theoretically, remittance inflows in Nepal could potentially be used to fuel consumption of goods and services that are imported (not natively produced), raising the import bill for the country instead of being used for funding infrastructure or capital assets. Therefore, remittance earnings could negatively impact economic growth in Nepal as money spent on imported products do not contribute to Nepal’s real GDP. Post Estimation Results A variety of statistical tests were used in this analysis to identify and address any econometric problems. Two tests were conducted to determine any evidence of multicollinearity using the regression in Model 4. Figure 5 shows a correlation matrix between all the variables used in this analysis. The matrix shows that there are no correlation coefficients of major concern since the highest correlation coefficient between two variables is 0.5042. A variance inflation factor test was also conducted to rule out evidence of multicollinearity. Figure 6 depicts the results of the VIF test. The figure shows that all the VIF scores are relatively close to 1, as the mean VIF score was 1.51. Thus, issues of multicollinearity can be seen as being negligible. Next, a Breusch Pagan test was conducted to test for heteroskedasticity within the data. Figure 7 shows the results for the Breusch Pagan test using Model 4. The null hypothesis here represents homoskedasticty. As the chi square probability is relatively 9 high while the chi squared test statistic is low, we fail to reject our null hypothesis. Thus, the option of constant variance or homoskedasticity prevails. While the data may exhibit constant variance, all regression estimates in this study were calculated using robust standard errors. Next, a Durbin Watson test was conducted to test for first order serial correlation. One limitation of this test is that it is unable to determine serial correlation for a dynamic model. Therefore, model 3 was used when running the Durbin Watson test. Figure 8 shows the results for the Durbin Watson test. The test statistic is roughly 1.77. As this d-statistic is relatively close to 2, there is evidence for minimal to no serial correlation within the distributed lag model. Lastly, a Dickey Fuller test was conducted to test for stationarity. Figure 9 shows the results of the Dickey Fuller test for a unit root using Model 4. The null hypothesis here represents non-stationarity. As the test statistic is relatively high while the p value is low, we have evidence to reject the null hypothesis of non-stationarity in favor of the alternative hypothesis of stationarity. 10 Conclusion & Recommendations In conclusion, amongst all the other determinants of Nepali economic growth considered in this analysis, remittance earnings were the only statistically significant variable: negatively impacting Nepal’s real GDP across all specification models. As previously mentioned, a potential reason for this could be the excessive purchasing of imported goods using remittance inflows. More research needs to be conducted on how exactly remittance earnings are spent within the country. For example, breaking down remittance earnings by whether they are consumed or saved. If so, what kind of investment accrues from such savings? Conversely, if remittance earnings are disproportionately used for importing necessary goods and services, as the Nepali market cannot fulfill the consumers’ needs. Given that we have determined a negative relationship between remittances and economic growth, it may be helpful to examine further why migrant workers search for work outside Nepal. A strong dependence on remittance earnings could indicate structural weaknesses within the Nepalese labor market. A labor market where the demand for labor falls far short of the supply of labor could signal inadequate performance by the economy’s public and private sectors, as the economy cannot fully take advantage of its demographic dividend. 11 References Ghimire, Luna, Ajay Shah, and Ram Phuyal. “Economic Growth in Nepal: Macroeconomic Determinants, Trends and Cross-Country Evidences.” Journal of World Economic Research 9 (May 2020). https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jwer.20200901.20. “Indian Economy Continues to Show Resilience Amid Global Uncertainties.” The World Bank, 2023. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/ press- release/2023/04/04/indian- economy- continues- to- show- resilience- amidglobal-uncertainties. Jha, Prabhat, and Shiva Chandra Dhakal. “Factors of Production Influencing Gross Domestic Product in Nepal.” Nepal Journal of Science and Technology 19 (October 2021): 41–45. https://doi.org/10.3126/njst.v20i1.39389. Ojha, Krishna Prasad. “Remittance Status and Contribution to GDP of Nepal.” NCC Journal 4 (July 2019): 102–112. https://doi.org/10.3126/nccj.v4i1.24743. Shakya, Prasiddha, and George Gonpu. “Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth in Nepal.” Nepal Public Policy Review 1 (October 2021): 32–44. https://doi.org/10.3126/ nppr.v1i1.43419. 12 Appendix Figure 1: Nepalese Real GDP from 1995-2021 reported in 2015 US Dollars Table 1: Summary Statistics of Independent and Dependent Variables Variable Obs Mean Std.dev Min Max Remittances 26 15.550 9.799 0.976 27.626 Inflation Rate 27 6.585 2.841 2.269 11.244 FDI 25 0.254 0.216 -0.0983 0.677 Agricultural Output 27 31.289 5.839 21.319 39.041 GDP Growth 26 4.247 2.308 -2.369 8.977 13 Figure 2: Percentage change in Nepalese Real GDP from 1995-2021 Figure 3: Agricultural Output and Remittance Inflows as a percentage of GDP over time 14 Figure 4: Imports as a perecentage of GDP over time Table 2: Time Series Regression Estimates of the Relationship between the Determinants of Economic Growth in Nepal (Real GDP) (1) (2) (3) (4) Key Variables Controls Distributed Lag Dynamic Model Remittance -1.264∗∗∗ -1.308∗∗∗ -1.330∗∗∗ -1.339∗∗∗ [0.0932] [0.206] [0.274] [0.271] Agriculture Output 0.0241 0.0372 0.0379 0.0274 [0.126] [0.121] [0.135] [0.134] -0.151 -0.153 -0.147 Inflation Rate [0.154] [0.178] [0.169] FDI 0.929 0.860 1.006 [2.374] [2.350] [2.305] -0.0186 -0.0715 Lagged InflationRate [0.151] [0.144] Lagged Remittances -0.211 -0.541 [0.204] [0.626] Lagged RealGDP -0.224 [0.447] Constant 3.757 4.123 4.292 5.982 [4.334] [4.677] [5.392] [5.216] Observations 25 25 24 24 R-Squared 0.141 0.175 0.173 0.194 RMSE 2.280 2.343 2.533 2.579 ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 15 Figure 5: Correlation test Figure 6: Variance Inflation Factor test Figure 7: Breusch Pagan test for heteroskedasticity 16 Figure 8: Durbin Watson test for first order serial correlation Figure 9: Dickey Fuller test for stationarity 17